Dynamic Neighborhood Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Based on Euclidean Distance for Solving the Nonlinear Equation System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A dynamic neighborhood strategy based on Euclidean distance was proposed, where individuals within the population were enabled to form appropriate neighborhoods, according to their own particle characteristics. This mechanism effectively avoids the misleading of the positions of high-quality particles by those with poor fitness values, thereby preventing the algorithm from falling into local optima.

- (2)

- A dual-strategy velocity-update mechanism based on Levy flight is proposed, which can balance the diversity of particles within the population and local search capability. In the early stage of the algorithm, the global search capability can be enhanced; in the later stage, particles can be enabled to rapidly converge near the optimal solution.

2. Problem Description and Basic PSO Algorithm

2.1. Problem Description

2.2. Basic PSO Algorithm

3. Dynamic Neighborhood Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Based on Euclidean Distance

3.1. Dynamic Domain Strategy Based on Euclidean Distance

3.2. Dual-Strategy Velocity-Update Mechanism Based on Levy Flight

3.3. Discrete Intersection

3.4. Procedure of EDPSO Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: Pseudocode of the EDPSO algorithm |

| Input: NP; FES; Max_FES; m; Γ; CR |

| Output: The ultimately obtained roots of the NESs. 1: Initialize population x (x = x1, x2, …, xNP) and velocity parameters v (v = v1, v2, …, vNP). 2: Compute initial fitness values using Equation (2) for all xi∈x. 3: While FES < Max_FES 4: for i = 1 to NP 5: Select neighborhood candidates for xi using Equation (6). 6: If randj < Pj 7: Localize j-th candidate within xn’s neighborhood 8: Endif 9: If randn > ψ 10: Update velocity via adaptive Levy flight (Equation (9)) 11: else 12: Update velocity via adaptive Levy flight (Equation (9)) 13: Endif 14: Construct experimental individual using Equation (4) 15: Derive new particle position using Equation (11) 16: Compute fitness of using Equation (2) 17: If f(xn) < facc 18: Add xi to external archive; reset xi’s position and velocity 19: Endif 20: Endfor |

| Endwhile |

4. Simulation Experiments and Analysis of Results

4.1. Test Functions and Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Contrastive Algorithms

4.3. Effect of Parameter Settings on Algorithm Performance

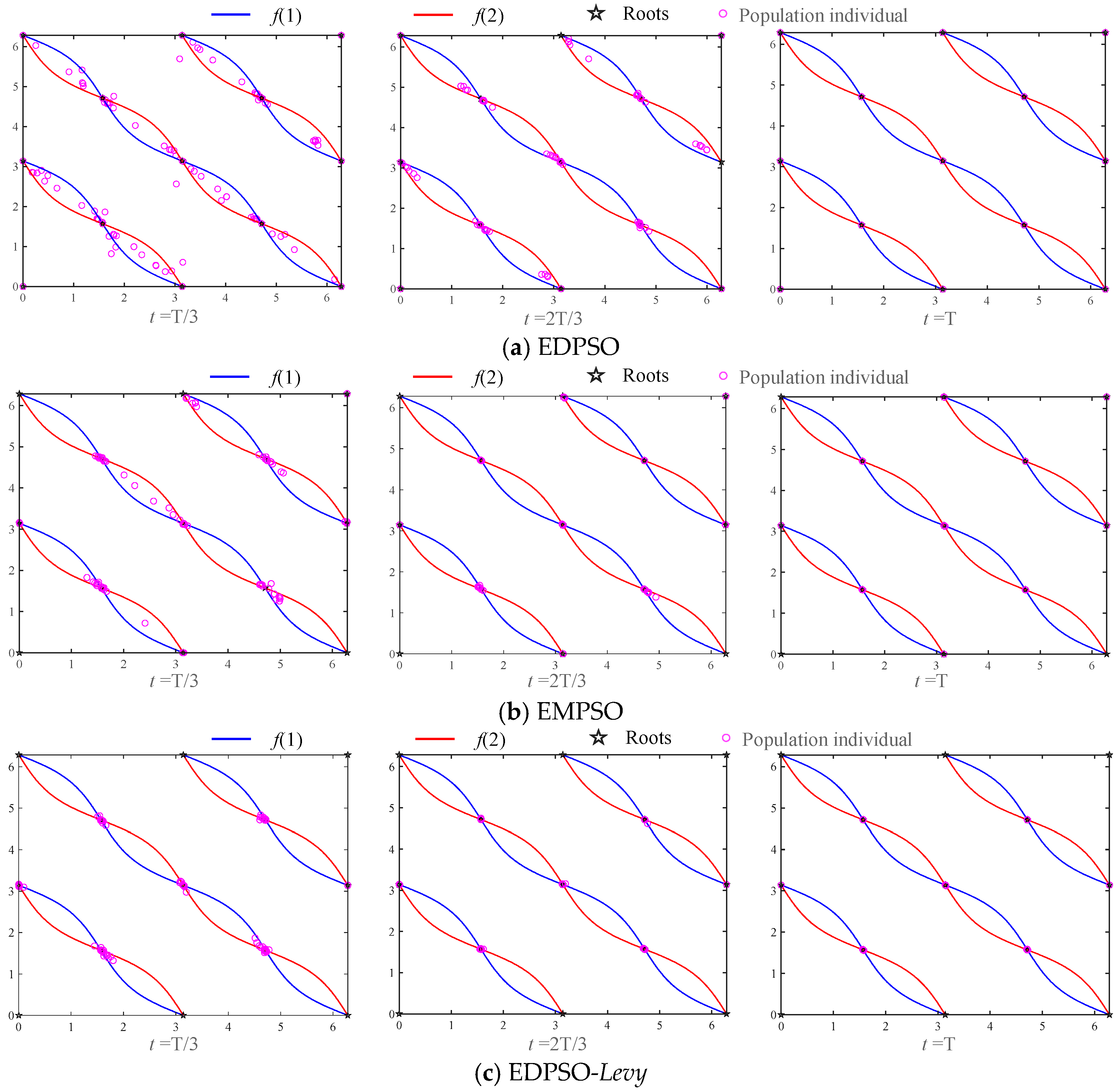

4.4. Impact of Improvement Strategies on the EDPSO Algorithm

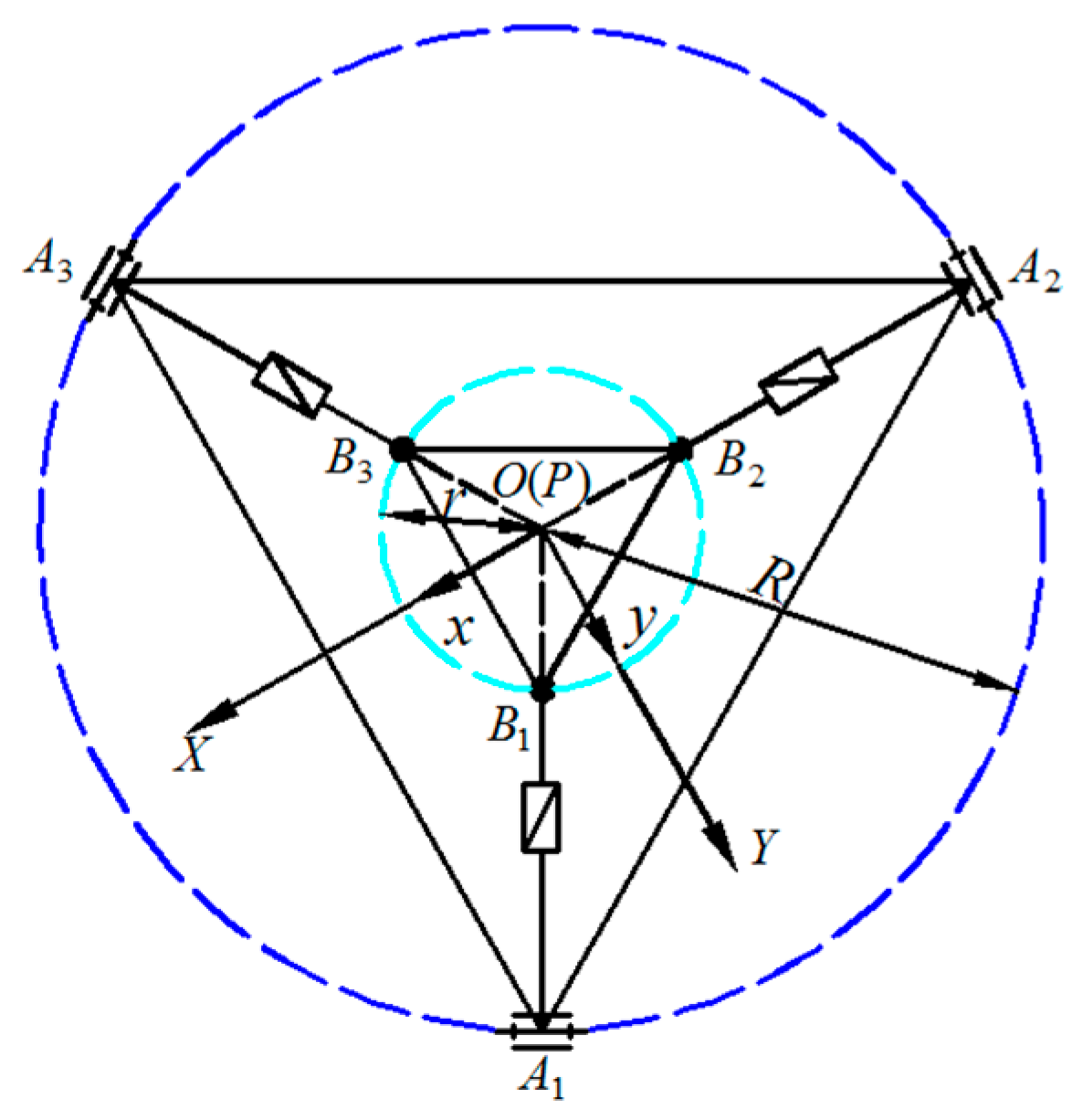

4.5. Mechanical Optimization: Example Application

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Maric, F.; Giamou, M.; Hall, A.W.; Khoubyarian, S.; Petrovic, I.; Kelly, J. Riemannian optimization for distance-geometric inverse kinematics. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 38, 1703–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Ji, A.; Che, L.; Yang, Z. Time-varying external archive differential evolution algorithm with applications to parallel mechanisms. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 114, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Gharbi, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Lee, H.P.; Che, L.; Ji, A. Dynamic neighbourhood particle swarm optimisation algorithm for solving multi-root direct kinematics in coupled parallel mechanisms. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 268, 126315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumam, P.; Abubakar, A.B.; Malik, M.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Pakkaranang, N.; Panyanak, B. A hybrid HS-LS conjugate gradient algorithm for unconstrained optimization with applications in motion control and image recovery. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2023, 443, 115304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.; Monteiro, M. A new approach based on the Newton’s method to solve systems of nonlinear equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2017, 318, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritton, K.S.; Seader, J.; Lin, W.-J. Global homotopy continuation procedures for seeking all roots of a nonlinear equation. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2001, 25, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D. Finding all the stationary points of a potential-energy landscape via numerical polynomial-homotopy-continuation method. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 025702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shao, H.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuo, Y. An efficient conjugate gradient-based algorithm for unconstrained optimization and its projection extension to large-scale constrained nonlinear equations with applications in signal recovery and image denoising problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2023, 422, 114879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Liang, X.; Li, M.; Jian, L. NGDE: A niching-based gradient-directed evolution algorithm for nonconvex optimization. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 5363–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Wu, G.; Pedrycz, W.; Wang, L. Integrating variable reduction strategy with evolutionary algorithms for solving nonlinear equations systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, M.; Jin, J.; He, X. A density clustering-based differential evolution algorithm for solving nonlinear equation systems. Inform. Sci. 2024, 675, 120753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.-X.; Cai, Z. Locating multiple optimal solutions of nonlinear equation systems based on multiobjective optimization, IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 2015, 19, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt, C.D., Jr.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Wang, L. Finding multiple roots of nonlinear equation systems via a repulsion-based adaptive differential evolution. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 50, 1499–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gong, W.; Liao, Z.; Wang, L. Hybrid niching-based differential evolution with two archives for nonlinear equation system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 7469–7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhu, F.; Gong, W.; Li, S.; Mi, X. AGSDE: Archive guided speciation-based differential evolution for nonlinear equations. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2022, 122, 108818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosan, C.; Abraham, X. A new approach for solving nonlinear equations systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.—Part A Syst. Hum. 2008, 38, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suid, M.H.; Ahmad, M.A.; Nasir, A.N.K.; Ghazali, M.R.; Jui, J.J. Continuous-time Hammerstein model identification utilizing hybridization of Augmented Sine Cosine Algorithm and Game-Theoretic approach. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumari, M.Z.M.; Ahmad, M.A.; Suid, M.H.; Hao, M.R. An Improved Marine Predators Algorithm-Tuned Fractional-Order PID Controller for Automatic Voltage Regulator System. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L. Neighborhood-based particle swarm optimization with discrete crossover for nonlinear equation systems. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2022, 69, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shorbagy, M.A. Chaotic noise-based particle swarm optimization algorithm for solving yystem of nonlinear equations. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 118087–118098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PSuganthan, P.N. Particle swarm optimiser with neighbourhood operator. In Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation—CEC99, Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 July 1999; Volume 3, pp. 1958–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Niching without niching parameters: Particle swarm optimization using a ring topology. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2009, 14, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brits, R.; Engelbrecht, A.P.; van den Bergh, F. A niching particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings of the 4th Asia-Pacific Conference on Simulated Evolution and Learning, Singapore, 18–22 November 2002; Volume 2, pp. 692–696. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, B.Y.; Suganthan, P.N.; Das, S. A distance-based locally informed particle swarm model for multimodal optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2012, 17, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnaweera, A.; Halgamuge, S.; Watson, H. Self-organizing hierarchical particle swarm optimizer with time-varying acceleration coefficients. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2004, 8, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamami, M.G.M.; Ismail, Z.H. A systematic review on particle swarm optimization towards target search in the swarm robotics domain. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; An, Q.; Lei, H.; Deng, Q.; Wang, G.-G. Survey of lévy flight-based metaheuristics for optimization. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.G. Particle swarm optimization algorithm and its applications: A systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 2531–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, B.Y.; Suganthan, P.N.; Liang, J.J. Differential evolution with neighborhood mutation for multimodal optimization. IEEE. Trans. Evol. Comput. 2012, 16, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Gong, W.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Hu, C. Solving nonlinear equations system with dynamic repulsion-based evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2018, 50, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Li, Y. Solving a new test set of nonlinear equation systems by evolutionary algorithm. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 20, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gong, W.; Wang, L. A clustering-based differential evolution with different crowding factors for nonlinear equations system. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2021, 98, 106733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhao, J.; Cui, H. Terminal constraint and mobility analysis of serial-parallel manipulators formed by 3-RPS and 3-SPR PMs. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 134, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | EDPSO | NCDE | NSDE | DR-JADE | LSTP | KSDE | HNDE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 0.9989 | 0.9751 | 0.9840 | 0.8957 | 0.9946 | 0.9720 | 0.9626 |

| SR | 0.9920 | 0.9400 | 0.9660 | 0.8860 | 0.9810 | 0.9550 | 0.9240 |

| EDPSO VS | RR | SR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R+ | R− | p Value | R+ | R− | p Value | |

| NCDE | 171.0 | 39.0 | 0.012622 | 171.0 | 39.0 | 0.012622 |

| NSDE | 125.0 | 85.0 | 0.444081 | 125.0 | 85.0 | 0.444081 |

| DR-JADE | 151.0 | 39.0 | 0.022302 | 142.0 | 68.0 | 0.157607 |

| LSTP | 137.5 | 52.5 | 0.083556 | 137.5 | 52.5 | 0.082006 |

| KSDE | 121.5 | 68.5 | 0.277241 | 122.0 | 68.0 | 0.266029 |

| HNDE | 158.0 | 52.0 | 0.044786 | 158.0 | 52.0 | 0.041822 |

| Index | m = 5 | m = 6 | m = 7 | m = 8 | m = 9 | m = 10 |

| RR | 0.9617 | 0.9930 | 0.9942 | 0.9965 | 0.9989 | 0.9961 |

| SR | 0.8990 | 0.9680 | 0.9750 | 0.9810 | 0.9920 | 0.9810 |

| Index | m = 11 | m = 12 | m = 13 | m = 14 | m = 15 | - |

| RR | 0.9948 | 0.9957 | 0.9951 | 0.9943 | 0.9942 | - |

| SR | 0.9710 | 0.9740 | 0.9740 | 0.9650 | 0.9650 | - |

| Index | Γ = 0.1 | Γ = 0.2 | Γ = 0.3 | Γ = 0.4 | Γ = 0.5 | Γ = 0.6 | Γ = 0.7 | Γ = 0.8 | Γ = 0.9 | Γ = 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 0.9967 | 0.9975 | 0.9978 | 0.9985 | 0.9963 | 0.9964 | 0.9968 | 0.9928 | 0.9943 | 0.9961 |

| SR | 0.9967 | 0.9975 | 0.9978 | 0.9985 | 0.9963 | 0.9964 | 0.9968 | 0.9928 | 0.9943 | 0.9961 |

| Index | CR = 0.1 | CR = 0.2 | CR = 0.3 | CR = 0.4 | CR = 0.5 | CR = 0.6 | CR = 0.7 | CR = 0.8 | CR = 0.9 | CR = 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 0.3235 | 0.4246 | 0.5876 | 0.7804 | 0.8562 | 0.9441 | 0.9419 | 0.9469 | 0.9483 | 0.9469 |

| SR | 0.1730 | 0.2390 | 0.3940 | 0.7050 | 0.8420 | 0.9300 | 0.9230 | 0.9350 | 0.9390 | 0.9340 |

| Index | EDPSO | EMPSO | EDPSO-Levy | EDPSO-CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 0.9989 | 0.9644 | 0.8008 | 0.6732 |

| SR | 0.9920 | 0.9070 | 0.7280 | 0.5830 |

| Num. | θ1 | θ2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1.63631461687421 | 63.5147256862694 |

| 2 | 63.3314584255204 | −6.02190524082467 |

| 3 | −64.4626549032305 | −62.7136209043545 |

| 4 | 1.63613571288348 | −63.5147650619382 |

| 5 | −62.4277287170268 | −64.5135098221173 |

| 6 | 64.4626615445065 | 62.7134310018056 |

| 7 | −63.3312267809634 | 6.02209000699150 |

| 8 | 62.4281274010519 | 64.5133664633938 |

| Index | EDPSO | NCDE | NSDE | DR-JADE | LSTP | KSDE | HNDE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 0.9800 | 0.8800 | 0.8600 | 0.9000 | 0.9400 | 0.9200 | 0.8600 |

| SR | 0.9975 | 0.9750 | 0.9800 | 0.9875 | 0.9925 | 0.9900 | 0.9826 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, A.; Yang, X.; Shen, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Kang, K. Dynamic Neighborhood Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Based on Euclidean Distance for Solving the Nonlinear Equation System. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17091500

Wei A, Yang X, Shen H, Liu H, Liu J, Kang K. Dynamic Neighborhood Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Based on Euclidean Distance for Solving the Nonlinear Equation System. Symmetry. 2025; 17(9):1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17091500

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Anruo, Xu Yang, Huan Shen, Hailiang Liu, Jiao Liu, and Kang Kang. 2025. "Dynamic Neighborhood Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Based on Euclidean Distance for Solving the Nonlinear Equation System" Symmetry 17, no. 9: 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17091500

APA StyleWei, A., Yang, X., Shen, H., Liu, H., Liu, J., & Kang, K. (2025). Dynamic Neighborhood Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Based on Euclidean Distance for Solving the Nonlinear Equation System. Symmetry, 17(9), 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17091500