Abstract

Batch processing machines (BPMs) are extensively present in high energy-consuming manufacturing processes such as casting, and they show some symmetries on adjacent batches and jobs within each batch. Preventive maintenance (PM) is very important for the stable running and energy saving of BPMs; however, PM in a parallel BPM shop is seldom studied. In this study, the energy-efficient parallel BPM scheduling problem with PM is considered and an imperialist competitive algorithm with three empires (TEICA) is presented to minimize makespan and total energy consumption. To obtain high-quality solutions, the number of empires is not used as a parameter and fixed at 3, a new way is applied to construct three initial empires, each of which has a new structure like two imperialists, a new assimilation is given, and an adaptive imperialist competition is implemented based on historical competition data. A number of computational experiments are conducted on 108 instances. The computational results show that the new strategies of TEICA are effective; TEICA can provide better results than all comparative methods on more than 90% instances of the considered BPM scheduling problem, and TEICA may be an effective way to solve other BPM scheduling problem.

1. Introduction

As a typical batch processing machine (BPM) scheduling problem, parallel BPM scheduling has attracted much attention [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. As the main approaches, meta-heuristics such as genetic algorithm (GA) [1,5], differential evolution (DE) [2,8], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [3] are often used, and heuristics [4,7] are also applied to solve the scheduling problem in parallel BPM shop.

There are some works on the uniform problem [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], which use algorithms based on linear programming and integer programming [9] and heuristic [9,10]. Some meta-heuristics are also applied, which are Pareto-based ant colony system [11], non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm-II (NSGA-II) and multi-objective imperialist competitive algorithm [12], DE [13], ant colony optimization [14,15], artificial immune system [16] and evolutionary algorithm [17]. Non-identical parallel BPM scheduling problem is solved by PSO [18], GA [19], fruit fly optimization algorithm [20], artificial bee colony (ABC) [21], shuffled frog-leaping algorithm (SFLA) [22], and teaching–learning-based optimization [23].

Many results are also obtained on unrelated parallel BPM scheduling. Shahidi-Zadeh et al. [24] proposed a harmony search algorithm to solve a multi-objective problem. A hybrid ABC with tabu search is applied to solve the problem with maintenance and deteriorating jobs [25]. A problem with different capacities and arbitrary job sizes is solved by a random key GA [26]. Sadati et al. [27] proposed fuzzy multi-objective discrete teaching–learning-based optimization and fuzzy NSGA-II. Zarook et al. [28] constructed an MILP model and provided six heuristics and a random key GA. To handle the problem in production systems under carbon reduction policies, Fallahi et al. [29] developed an MILP model, NSGA-II, and a multi-objective gray wolf optimizer. An SFLA with variable neighborhood search is designed for solving problems with nonlinear processing time [30]. A tabu-based adaptive large neighborhood search algorithm is presented by Xiao et al. [31], which renews the best known solutions of 55 instances. A problem with 2D packing constraint, non-identical sizes, unequal release dates, and due dates is solved by using an adaptive large neighborhood search [32].

BPMs are often present in high energy-consuming processes such as casting and energy-efficient BPM scheduling has attracted much attention in recent years [23,29,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. With respect to the energy-efficient parallel BPM scheduling problem, Jia et al. [33] and Wang et al. [34] proposed a bi-objective ant colony optimization and a three-population co-evolutionary algorithm to minimize makespan and total energy consumption. For the problem with time-of-use electricity tariffs, Zhou et al. [35] developed a multi-objective DE algorithm for the problem with dynamic job arrivals, and Tian and Zheng [36] constructed a mixed-integer linear programming formulation and proposed a branch and price algorithm. Li et al. [17,37] developed a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for uniform and non-identical problems with different job sizes and release times. Yang [38] presented an online algorithm for problems in the steel making process. Jiang et al. [39] proposed a modified benders decomposition and meta-heuristics for problems in the semiconductor burn-in test process. Schorn et al. [40] solved the problem with release time by genetic programming. Abedi et al. [41] developed a tabu search method for problems with incompatible families and release times. Wang et al. [23] dealt with a fuzzy problem with machine eligibility and sequence-dependent setup time in fabric dyeing processing using a dynamical teaching–learning-based optimization. Wang et al. [42] presented a multi-objective mixed-integer programming model and a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition combined with variable neighborhood search for problems with preventive maintenance (PM).

As stated above, many results are obtained on parallel BPM scheduling; uniform problem, non-identical problem, unrelated problem, and energy-efficient problem are often considered; scheduling of parallel BPMs in real-life manufacturing processes such as fabric dyeing and semiconductor burn-in test is frequently investigated; various processing conditions and constraints, including machine eligibility, are also handled. However, some constraints are seldom dealt with, for example, PM is often applied to prevent potential failures and serious accidents in parallel machines, and the parallel machine scheduling problem (PMSP) with PM is frequently addressed [43,44,45]. To the best of our knowledge, related works on PM in parallel BPM shops are seldom conducted. A BPM is often a furnace for heating and melting and a high energy-consuming machine; its stable running and avoidance of failure and accidents can directly affect the production efficiency and energy consumption of a manufacturing process, so it is necessary to the solve energy-efficient parallel BPM scheduling problem with PM.

The imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA) is a meta-heuristic illuminated by the historical phenomena of imperialism and colonialism. Unlike the existing meta-heuristics such as GA and SFLA, ICA has good neighborhood search ability, effective global search property, good convergence rate, and flexible structure [46]. In recent years, ICA has been extensively applied to solve various production scheduling problems such as PMSP [47], flexible job shop scheduling [48,49], hybrid flow shop scheduling [50,51], and assembly scheduling [52]; however, ICA is seldom applied to solve parallel BPM scheduling. ICA has successfully been applied to solve PMSP and results revealed that ICA has a strong exploration–exploitation balance and significantly outperforms the best-performing algorithms in the literature. When all machines of PMSP are replaced with BPMs, PMSP is extended to the parallel BPM scheduling problem. The advantages of ICA in solving PMSP show that ICA has a potential advantage in handling parallel BPM scheduling, so ICA is chosen in this study.

In this paper, the energy-efficient parallel BPM scheduling problem with PM is considered, and a new imperialist competitive algorithm with three empires (TEICA) is presented to minimize makespan and total energy consumption. In TEICA, the number of empires is fixed at 3 and not used as a parameter. A new way is applied to construct three initial empires, each of which has a new structure resembling two imperialists, and exploration ability can be intensified. A new assimilation is given and an adaptive imperialist competition is implemented. A number of computational experiments are conducted on 108 instances. The computational results demonstrate that new strategies, such as a new empire structure, are effective, and TEICA has promising advantages in solving the BPM scheduling problem being considered.

2. Problem Description

The parallel BPM scheduling problem with PM is shown below. There are n jobs and m unrelated parallel BPMs . Each job can be processed on any BPM. Table 1 describes some notations. indicates the processing time of on . may be size, weight. Size means the number of , is the weight in the fabric dyeing process. Jobs can be grouped into a batch according to the type of job and the capacity of the BPM. In batch , all jobs belong to the same type and capacity constraint is met, that is, the sum of index of all jobs in the batch cannot exceed , for example, the sum of size or weight of all jobs is less than or equal to . . In a batch, all jobs of the batch start at the same time and also end at the same time.

Table 1.

Notation and description.

PM is considered. There is a time interval between two consecutive PMs, during which jobs are processed. For , indicates the length of the interval, denotes the duration of PM, and the start time of the g-th PM is , that is, the processing of a job cannot be finished when time reaches, PM will be first handled and then the job is processed.

The following constraints on jobs and machines are considered:

- Each batch can be processed on only one machine at a time.

- Each machine handles at most one batch at a time.

- The operations cannot be interrupted.

- All the machines are available at time zero.

The problem is composed of three sub-problems: machine assignment, batch formation, and scheduling. The goal of the problem is to minimize makespan and total energy consumption when all sub-problems are solved and all constraints are met.

where indicates energy consumption per unit time when is in processing mode, idle mode and maintenance mode respectively, , are total idle time and total maintenance time.

There are some symmetries on each BPM. On the BPM , two adjacent batches between two processing machines are exchanged with each other. Two objectives are kept invariant, which is symmetry, but when two batches on different BPM are swapped, objectives will vary and no symmetry exists. For two objectives, the conflict means that when one objective is improved, the other objective may deteriorate. For parallel BPM scheduling, for a given , there exist many different schedules with the same , and these schedules have different . When diminishes, may increase, so and conflict each other.

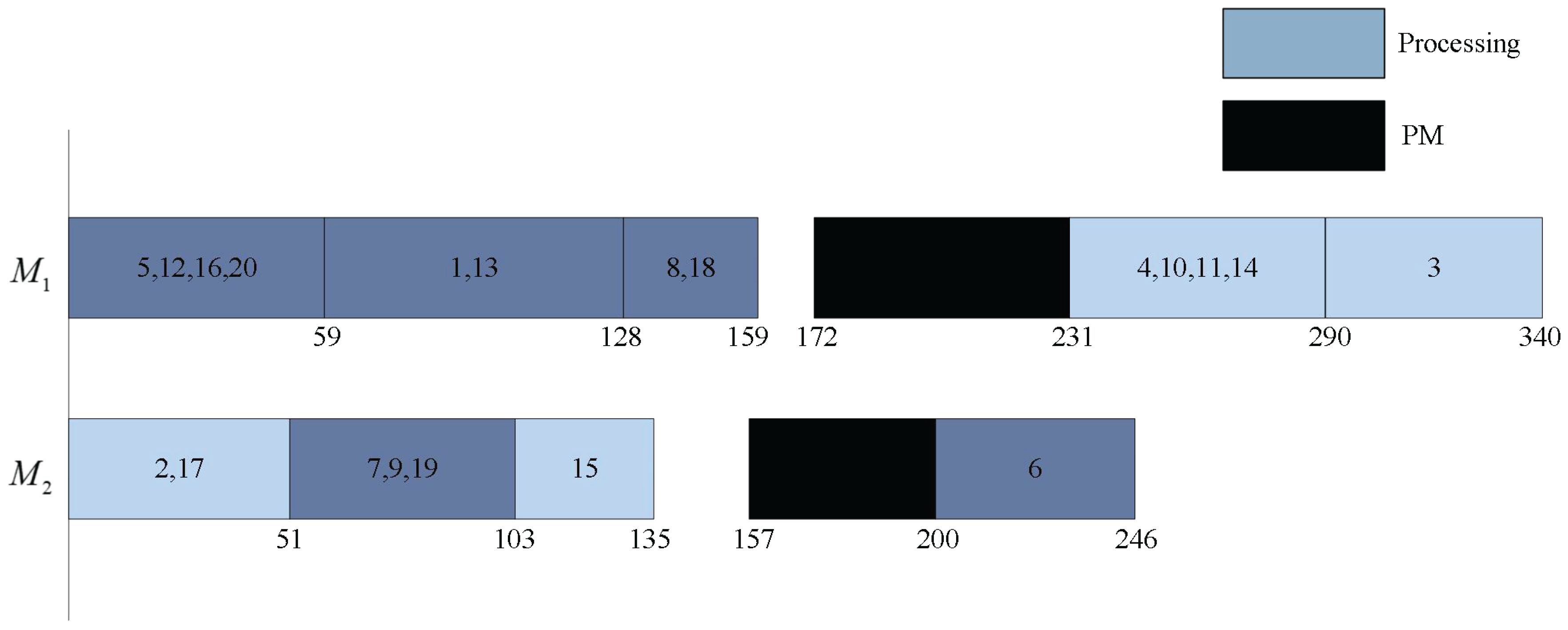

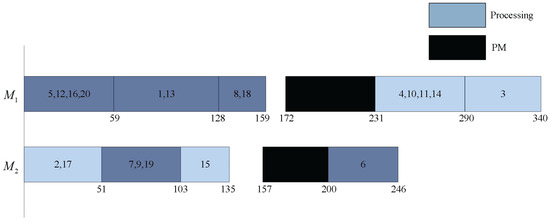

Figure 1.

A schedule of the example.

In the above equation, the first part is about jobs and the second is about the remaining jobs. Figure 1 shows a schedule of the example. The numbers in each box represent the jobs in a batch; for example, the first batch on is composed of jobs 5, 12, 16, 20.

For the problem with and , indicates x dominates y and is defined as follows: if , , and or , then . If and are not met, then are non-dominated by each other.

3. TEICA for Energy-Efficient Parallel BPM Scheduling with PM

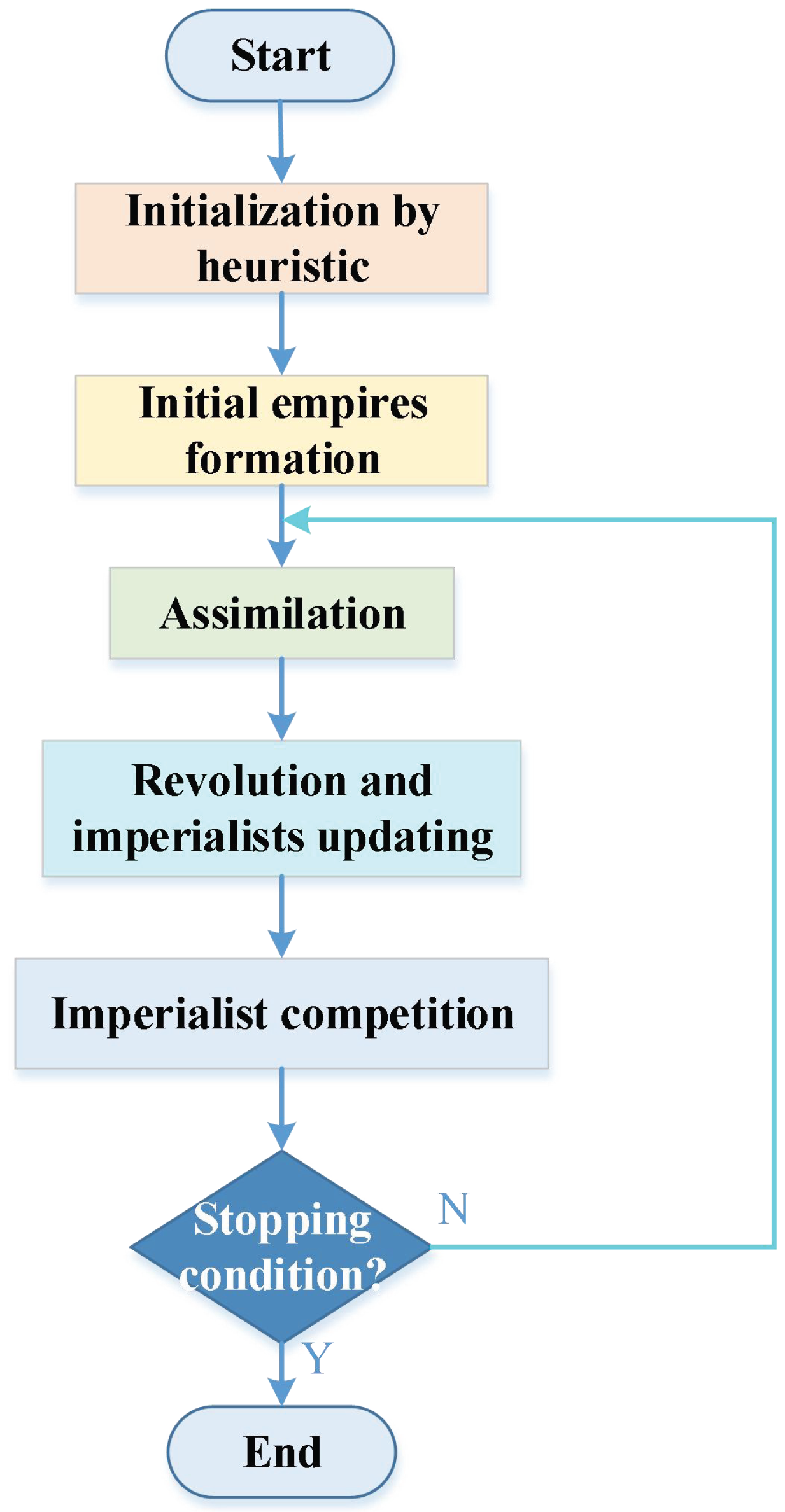

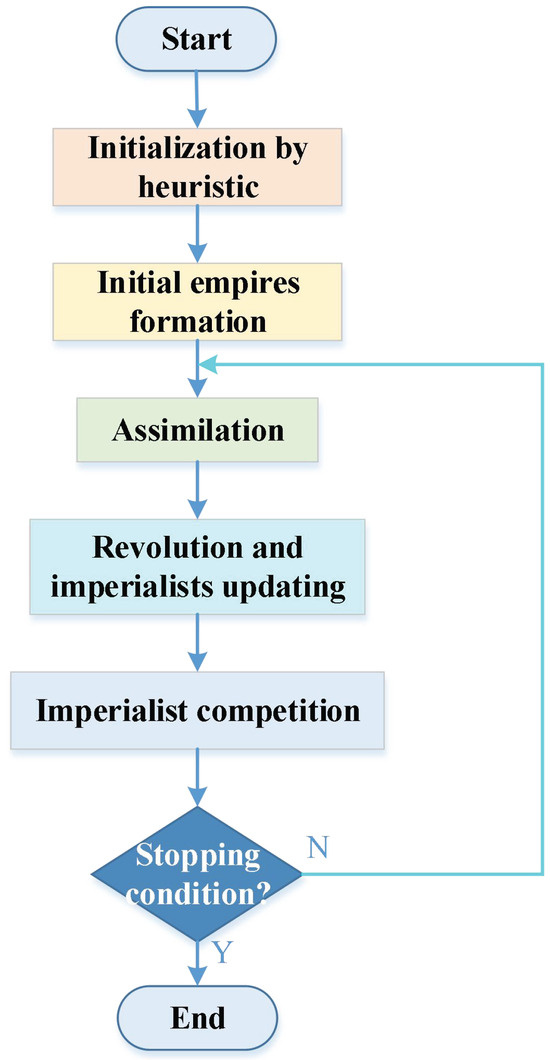

ICA is composed of initial empire formation, assimilation, revolution, and imperialist updating in each empire and imperialist competition. In TEICA, there are three fixed empires, each of which has two imperialists, and new assimilation and imperialist competition are given because of the fixed number of empires. Figure 2 shows the flow chart of TEICA, in which initial empire formation is used to construct initial empires, assimilation and revolution are main steps to produce new solutions, and imperialist competition is used to move colonies between empires. The stopping condition is often the running time of an algorithm.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of TEICA.

3.1. Initialization and Initial Empires

Two-string representation is used. For the problem with n jobs and m BPMs, its solution is represented as a machine assignment string and a scheduling string , where and are the assigned BPM and a real number for job .

The decoding process is shown below. For each BPM , decide all jobs assigned on according to machine assignment string and sort all jobs on in the ascending order of their , obtain a permutation of all jobs, construct a empty batch , repeat the following steps until the permutation is empty: for the first job on the permutation, , delete from the permutation, then choose all jobs with the type of from the permutation sequentially under capacity constraint and add all chosen jobs into and delete the chosen jobs from the permutation, , let be empty. After batches are formed, then all batches are processed on according to sequence .

For the example in Section 2, a possible solution is and . On , jobs are assigned on , a permutation is obtained, then , , , .

A simple heuristic is used, in which for each job , a BPM with the smallest is chosen as , and a scheduling string is randomly produced. The initial population P is generated as follows. The heuristic is applied to produce six initial solutions, and initial solutions are produced stochastically.

In general ICA, each country corresponds to a solution of the problem and cost [46] is defined for each x. The better the solution is, the smaller the cost is. In population P, there are imperialists and colonies, . There are empires, each of which is composed of an imperialist and colonies. When initial empires are constructed, solutions with the smallest cost are first chosen as imperialists, then for each imperialist , its normalized cost , power , [46] are given; colonies are randomly selected for and empire k is obtained with and its colonies.

where is an integer being closet to x.

A new way is proposed to produce three initial empires, as shown below.

(1) Define six solutions produced by the heuristic as imperialists , randomly choose two imperialists and add them into empire 1, then stochastically select the other two imperialists and include them into empire 2, and add the remaining two imperialists into empire 3.

(2) Execute non-dominated sorting [53] on all solutions of population P, define for each .

(3) Compute and and randomly select colonies for empires 1,2,3.

Suppose that are in empire 1, are in empire 2 and are in empire 3, then is computed below.

where and are rank value and crowding distance of x obtained by non-dominated sorting.

When and are computed, and substitute for respectively. When are calculated, of Equation (6) is replaced with .

Unlike the existing ICA, TEICA only has three empires, and each empire has two fixed imperialists; this is a new structure. Moreover, is fixed at 3, and a parameter is reduced. After three empires are constructed, new assimilation and revolution are applied to improve solutions for each empire, and communication between empires is executed by imperialist competition; as a result, two objectives can be minimized continuously.

3.2. New Assimilation and Revolution

Assimilation is the main step for producing new solutions. In the assimilation process, a colony in each empire moves along with e direction toward its imperialist. The moving distance is a random number gotten by random distribution in interval , where and e is the distance between the colony and the imperialist. Setting causes the colony to move toward the imperialist direction. However, imperialist cannot absorb their colonies in direct movement, resulting in a deviation from the direct line. The deviation is represented by , which follows a uniform distribution in , where is an arbitrary parameter.

To solve production scheduling problems, including parallel BPM scheduling, the above assimilation is often discretized because coding strings of scheduling problems often have special meaning and constraints; for example, in machine assignment, is a BPM and cannot be updated by using the above method.

In general ICA, each empire has only one imperialist. If the imperialist of an empire cannot be updated in some generations, the solution diversity in the empire will diminish greatly and search may stagnate. In TEICA, two imperialists are allocated in each empire, and colonies move to two imperialists; the above stagnation can be avoided effectively. A new assimilation is given because of the new structure of empires.

A new assimilation is described below for empire k.

- (1)

- For each colony x of empire k, randomly choose an imperialist, suppose is chosen, execute two-point crossover on machine assignment strings of , obtain a new solution , if or are non-dominated each other, then and update external archive with x; otherwise, produce by two-point crossover on scheduling string of and update according to the above condition.

- (2)

- For imperialist , execute two-point crossover on machine assignment string and scheduling string on , respectively and update and using the same way of step (1); then perform the same step for .

In Step 2, for , two-point crossovers on , are performed and is renewed. When imperialists are improved continuously in each empire, exploration ability will be intensified.

is used to store non-dominated solutions produced by TEICA and updated in the following way: add x into , compare all solutions of based on Pareto dominance and delete all dominated solutions.

Revolution is a step of ICA, which is similar with the mutation of GA. It is applied to increase exploration and prevents the early convergence to local optima. Revolution is shown as follows. For empire k, for each colony x of empire k, if random number , then perform multiple neighborhood search on x, where follows a uniform distribution on [0, 1].

Seven neighborhood structures are used. is shown below: randomly choose a BPM with and a BPM , then randomly choose a job from and move it to , that is, let be . are similar with , in , is the BPM with the biggest completion time and is the BPM with the smallest completion time; in , is the BPM with the biggest energy consumption and indicates the BPM with the smallest energy consumption. is described below: randomly select two BPMs , , exchange a randomly chosen batch of and a stochastically chosen batch on , that is, all jobs of are assigned to and all jobs of are allocated to . , , are swap operator, insertion operator and invert operator of scheduling string.

Two using sequences of seven neighborhood structures are applied, which are and .

Multiple neighborhood search is depicted as follows: for solution x, randomly choose a using sequence, let , repeat the following steps until : produce a new solution z by using the th neighborhood structure in the chosen sequence, if or are non-dominated each other, then and update ; otherwise, .

After assimilation and revolution are completed, in each empire k, non-dominated sorting [53] is performed on all solutions; choose two solutions with the smallest rank and the biggest crowding distance as new imperialists.

3.3. Imperialist Competition

Imperialist competition is an important step based on the total cost of empire.

The steps of imperialist competition are shown as follows:

- (1)

- Calculate total cost , [46] for each empire k;

- (2)

- Compute the power [46] for each empire k;

- (3)

- Construct a vector and choose an empire k with the biggest ;

- (4)

- Assign the weakest colony from the weakest empire to the chosen empire.

In the above,

where in Equation (11), indicates average cost of all colonies in empire k, is a positive number between 0 and 1 and close to 0. denotes a random number following the uniform distribution in [0, 1].

In the existing ICA, the number of empires diminishes when imperialist competition is performed continuously. In TEICA, there are three fixed empires in the whole search procedure and no movement of the colony is performed; a new imperialist competition is presented to adapt to the above new situations.

is an integer for empire k, if empire k cannot win, than ; otherwise, .

The new imperialist competition is shown below:

- (1)

- Calculate , and decide the winning empire in terms of the above steps, suppose empire 1 wins.

- (2)

- For empire 1, choose R colonies with the smallest rank and the biggest crowding distance, for each chosen colony x, execute two-point crossover on machine assignment string and scheduling string like step 1 of assimilation, then perform multiple neighborhood search on x.

- (3)

- For empire k with , suppose that , choose the best solutions from empire 1 and the best solutions from empire 2, then for each chosen solution, perform multiple neighborhood search on it and the newly produced solution substitutes for the worst R solutions of empire 3.

In step (1), is defined directly. In step (2), R best colonies can be improved by crossover and multiple neighborhood search acts, and exploration ability can be intensified.

where , is the set of all colonies of empire k.

In step (3), when multiple neighborhood solutions exist on x, the new solution is compared with the worst R solution of empire 3 and substitutes for one of the worst R solutions in empire 3 if the condition in the above neighborhood search is met.

In step (3), means that empire 3 cannot win in steps (1) (2) in continuous A generation, empire 3 cannot win and R extra searches are also cannot be obtained and the winning possibility of empire 3 will greatly diminish, in this case, historical competition results of each empire are used, excessive competition also occurs. To avoid this case, empire 3 is intensified by using some of the best solutions from empires 1 and 2.

If just two initial empires are constructed, a vector based on will just have two elements and the worst empire will be eliminated in the limited generations, as a result, diversity of population will diminish and the effect of imperialist competition is limited. When three empires are used, there are good balance on diversity of population and effect of imperialist competition between two empires and empires; no elimination and the avoidance of excessive competition can keep high diversity and good effect of imperialist competition, so is fixed at 3.

3.4. Algorithm Description

The main steps of TEICA are shown below:

- (1)

- Produce initial population P by heuristic and random way; let .

- (2)

- Construct three initial empires; let , .

- (3)

- Perform new assimilation in each empire.

- (4)

- Execute revolution and update two imperialists in each empire.

- (5)

- Perform new imperialist competition.

- (6)

- ; if stopping condition is met, then stop the search. Otherwise, go to step (3).

Unlike the existing ICAs, TEICA has the following features. Only three empires are constructed and is fixed at three and not used as parameter, to adapt this new situation, each empire has new structure with two imperialists and a novel assimilation is presented to adapt to this structure; no elimination of empire is considered, new imperialist competition and an effective way for excessive competition are given. On the other hand, some new things are added into TEICA, and its implementation is more difficult than the standard ICA.

4. Computational Experiments

Extensive experiments are conducted to test the performance of TEICA for the considered problem. Experiments are implemented by using Microsoft Visual C++ 2019 and run on 8.0G RAM 2.4GHz CPU PC.

4.1. Instances, Metrics and Comparative Algorithms

One hundred eight instances are used, which have the following data: , , , , when , ; when , ; when , . is given by Li et al. [16].

Li et al. [17] proposed an algorithm named C-NSGA-A for minimizing maximum lateness and total pollution emission cost. Jia et al. [33] presented bi-objective ant colony optimization (BOACO) to minimize total energy consumption and makespan. When PM is added into the decoding procedure of C-NSGA-A and BOACO, two algorithms can be directly applied to solve our problem, so they are chosen as comparative algorithms.

To show the effectiveness of new strategies of TEICA, an ICA is constructed, which has the same steps as the standard ICA [46]. In ICA, is a parameter, empires, assimilation, revolution, imperialist competition are implemented according to reference [46], When colony moves its imperialist, global search is executed in the same way as assimilation of TEICA.

Three metrics are used. Metric [54] is applied to compare the approximate Pareto optimal set obtained by algorithms.

Metric [55] is the ratio of to , where is the non-dominated set of Algorithm l, the reference set consists of the non-dominated solutions in the union of non-dominated sets of all algorithms.

[56] is used to calculate the distance of the non-dominated set relative to a reference set .

where is the distance between a solution x and a reference solution y in the normalized objective space.

4.2. Parameter Settings

TEICA has the following parameters: , and the stopping condition. In this study, CPU time is adopted as the stopping condition. We found through experiments that TEICA, ICA, C-NSGA-A, and BOACO can reach a stable set of solutions on all instances when the second CPU time reaches , so this CPU time is used as the stopping condition for four algorithms.

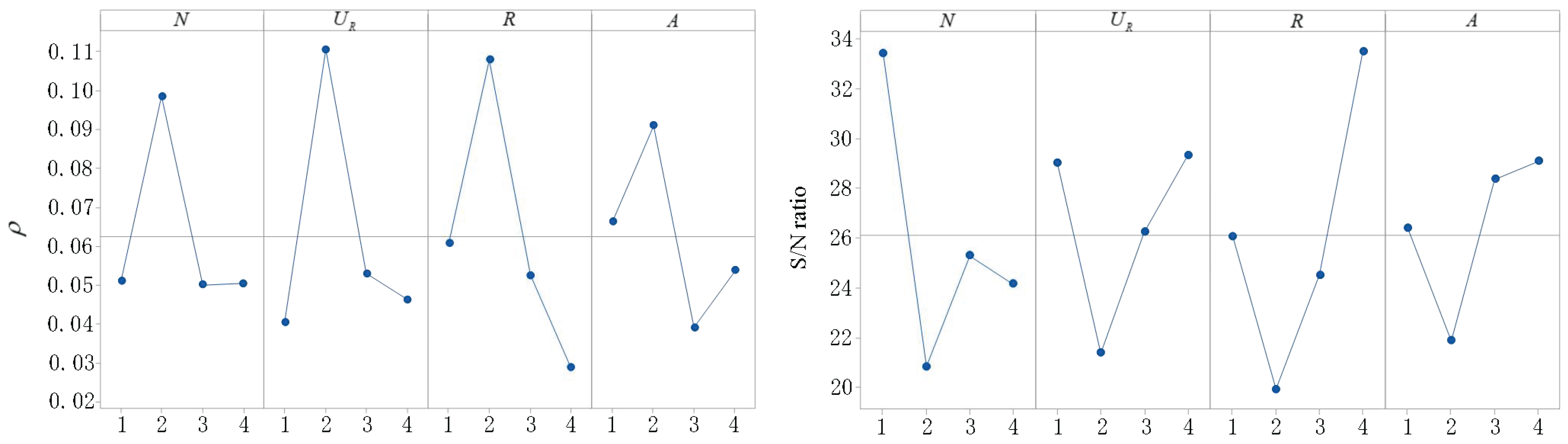

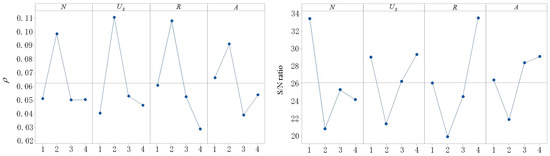

To decide the settings for other parameters, the Taguchi method [57] is applied on instance 37. Table 2 describes the levels of each parameter. The orthogonal array is executed. TEICA with each parameter combination runs 10 times for the chosen instance.

Table 2.

Level of the parameters.

Figure 3 shows the results of and S/N ratio, which is . It can be found from Figure 3 that TEICA with the following combination can obtain better results than TEICA with other combinations, so the above parameter settings are adopted.

Figure 3.

Main effect plot for and S/N ratio.

ICA has and the above stopping condition. These settings are obtained by experiments.

With respect to C-NSGA-A and BOACO, their parameter settings, except the stopping condition, are directly chosen from references [17,33] and used in this study. Experiments are conducted to decide the parameters of references [17,33] under the above CPU time as stopping condition, the experimental results show that the parameter settings of each comparative algorithm are still effective, so they are kept.

4.3. Results and Discussions

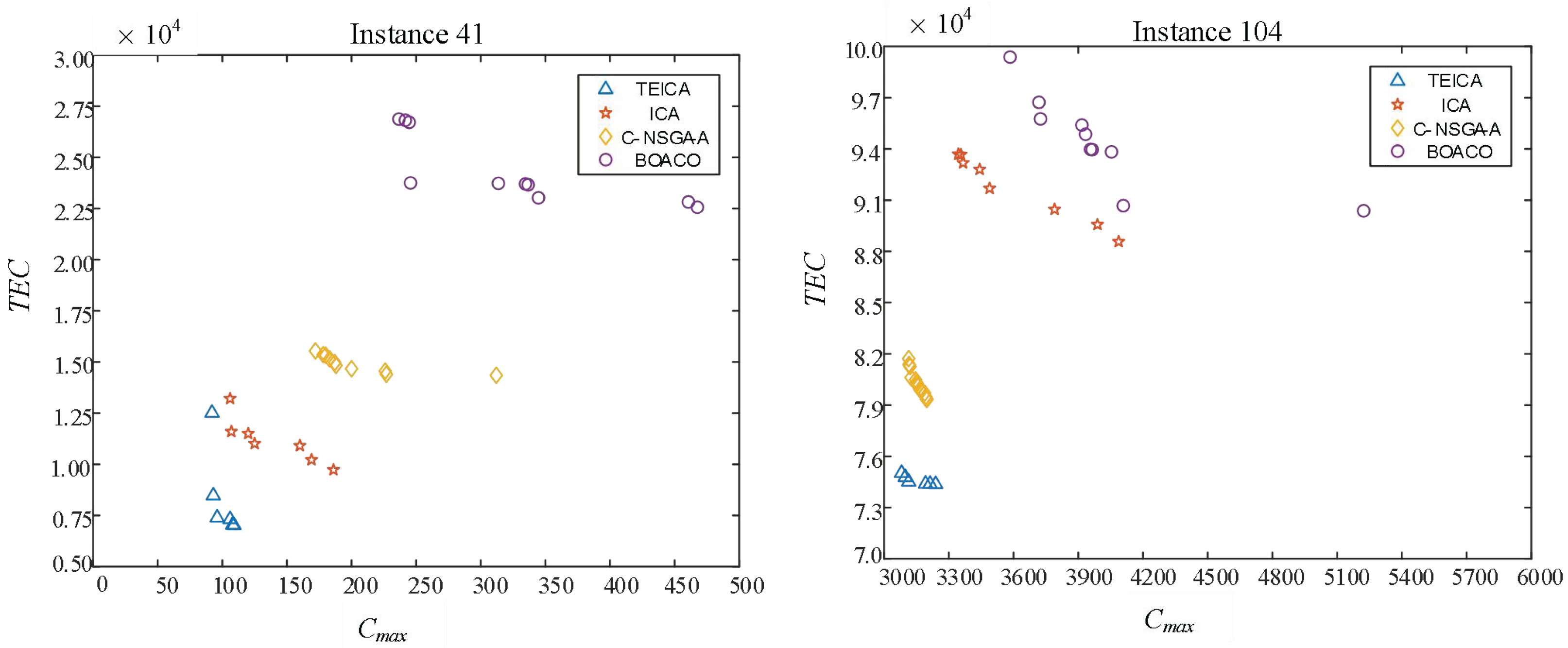

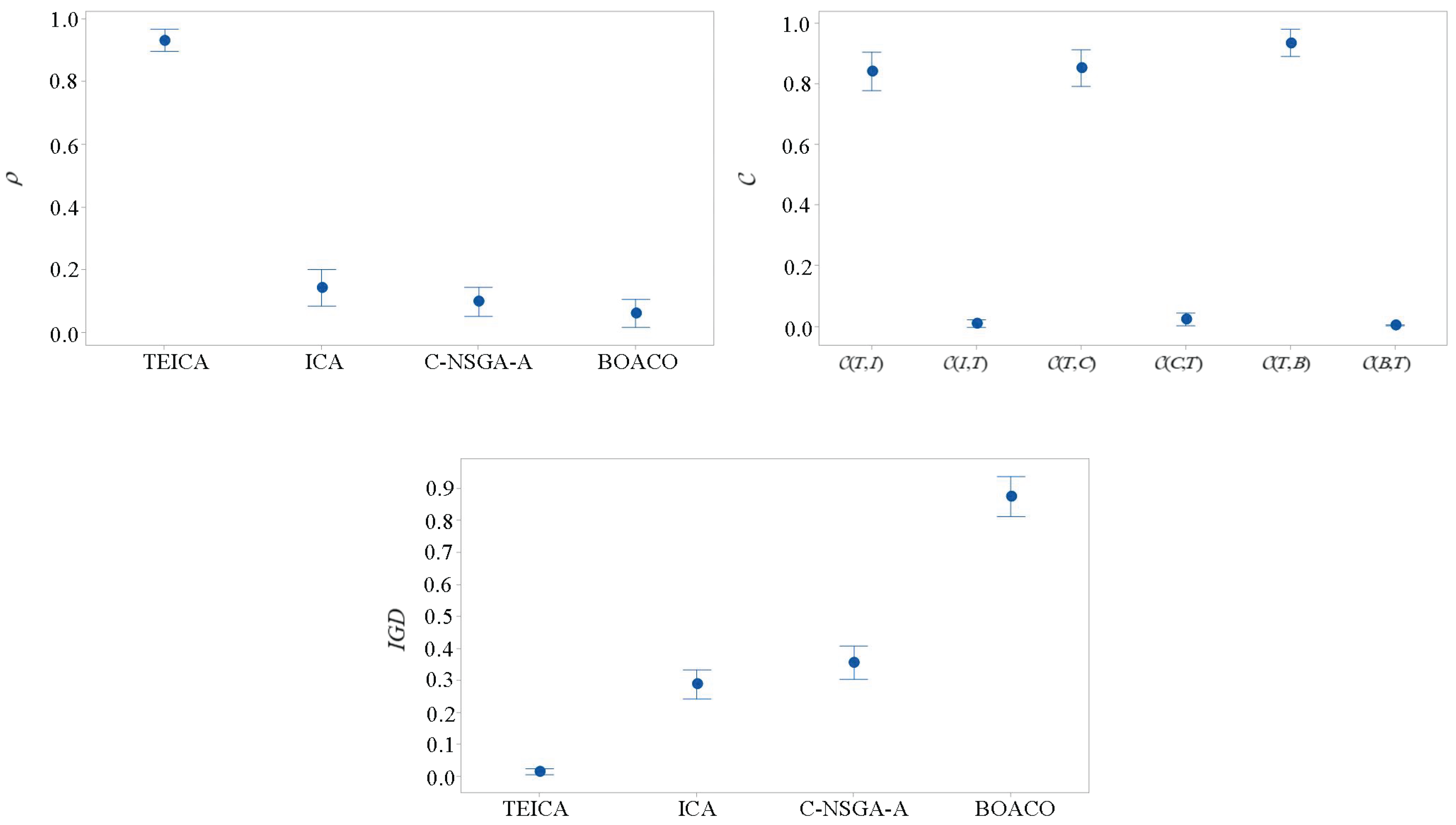

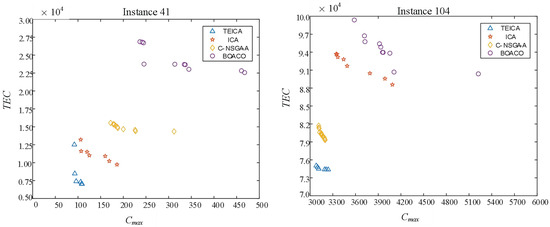

TEICA, ICA, BOACO, and C-NSGA-A are compared. Each algorithm randomly runs 10 times for each instance. Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 describe the corresponding results of four algorithms. T, I, C, B represent TEICA, ICA, C-NSGA-A, and BOACO. Figure 4 shows distributions of non-dominated solutions, each point indicates the non-dominated solution of an algorithm. Table 6 gives results of paired sample t-test, where p-value being less than 0.05 for t-test (A,B) means that A performs better than B in the statistical sense. Figure 5 gives mean plot with 95% confidence interval.

Table 3.

Computational results of four algorithms on metric .

Table 4.

Computational results of four algorithms on metric .

Table 5.

Computational results of four algorithms on metric .

Figure 4.

Distribution of non-dominated solutions of four algorithms.

Table 6.

Results of paired sample t-test.

Figure 5.

Mean plot with 95% confidence interval.

Table 3 shows that TEICA obtains a smaller than ICA on 101 instances. The significant performance differences between TEICA and ICA can be found in Figure 4 and Figure 5. It can be seen from Table 4 that of TEICA is better than that of ABC on more than 90% instances, and of TEICA is 1 on 89 instances, that is, TEICA provides all members for reference set . As shown in Table 5, TEICA produces smaller (I,T) than (T,I) on 97 of 108 instances and obtains (T,I) of 1 on 84 instances. These results show that all solutions of ICA are dominated by non-dominated solutions of TEICA on most of the instances, and TEICA converges significantly better than ICA. The new strategies of TEICA really have a positive impact on the performance, so the new strategies are effective.

When TEICA is compared with C-NSGA-A, it can be found that TEICA performs better than C-NSGA-A on most of instances. As shown in Table 4, TEICA obtains a bigger than C-NSGA-A on 101 instances, and the of TEICA is 1.0 on 90 instances, that is, all members of reference set are generated by TEICA. TEICA also performs better than C-NSGA-A on because TEICA obtains a better than C-NSGA-A on 101 instances. Table 5 shows that TEICA provides smaller (C,T) than (T,C) on 99 of 108 instances and obtains (T,C) of 1 on 84 instances. The above analyses show that TEICA can provide better results than C-NSGA-A. Table 6 reveals that performance difference between TEICA and C-NSGA-A is significant in the statistical sense. Figure 4 and Figure 5 also show that the above conclusion is still effective.

It can also be concluded from Table 3 to Table 5 that TEICA outperforms BOACO on three metrics. TEICA obtains smaller (B,T) than (T,B) on 103 instances, gets bigger than BOACO on nearly all instances and better than TICA on 102 instances. On the other hand, TEICA has of 0, of 1 and (T,B) of 1 on most of instances, that is, there exist notable performance differences between TEICA and BOACO. This conclusion can also be drawn from Table 6 and Figure 4 and Figure 5, thus, based on the above analyses, it can be concluded that TEICA can provide better results than the two comparative algorithms.

The good performance of TEICA mainly result from its new strategies. Three empires with new structures exist in the whole search procedure of TEICA, and their competition is implemented fully; as a result, high diversity of population can be kept and exploration ability is intensified because of new assimilation. Thus, TEICA is a very competitive method for the considered BPM scheduling problem.

5. Conclusions

PM and energy-efficient scheduling are seldom considered in a parallel BPM shop. In this study, energy-efficient parallel BPM scheduling with PM is considered, and a novel algorithm named TEICA is presented to minimize makespan and total energy consumption. In TEICA, the number of empires is not used as a parameter and is fixed at 3. To adapt to this new situation, a new way is applied to construct three initial empires with a new structure, a new assimilation is given, and an adaptive imperialist competition is implemented. This is a new path to designing ICA, and this path also has limitations such as the increase of implementation difficulty. A number of computational experiments are conducted on 108 instances. The computational results show that the new strategies of TEICA are effective, and TEICA has promising advantages in solving the considered BPM scheduling problem.

The BPM is frequently used in real-world manufacturing industries such as casting and textiles. The BPM scheduling problem has higher complexity than the classical scheduling problem; batch formation is added. In real-life factories, hybrid flow shop scheduling problems with BPMs and flexible job shop scheduling with BPMs extensively exist in casting, textile, semiconductor, and steel making, in which batch production is part of the factories. This feature leads to great challenges in solving them. We will try to solve them by using meta-heuristics with new optimization mechanisms including learning, cooperation, feedback, and competition. BPM scheduling problems in real-life manufacturing processes are also our future topic. We will try to refine and solve BPM scheduling for production processes in manufacturing companies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L.; methodology, M.L.; software, M.L.; validation, D.L.; formal analysis, D.L.; investigation, D.L.; resources, M.L.; data curation, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L.; visualization, M.L.; supervision, D.L.; project administration, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.61573264).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Koh, S.G.; Koo, P.H.; Ha, J.W.; Lee, W.S. Scheduling parallel batch processing machines with arbitrary job sizes and incompatible job families. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2004, 42, 4091–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.J.; Wang, X.H. Weighted nested partitions based on differential evolution (WNPDE) algorithm-based scheduling of parallel batching processing machines (BPM) with incompatible families and dynamic lot arrival. Int. J. Comput. Integ. Manuf. 2011, 24, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Chu, C.B.; Jia, Z.H. Parallel batch processing machines scheduling in cloud manufacturing for minimizing total service completion time. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 146, 105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahm, C.; Wahl, S.; Tuma, A. Scheduling parallel serial-batch processing machines with incompatible job families, sequence-dependent setup times and arbitrary sizes. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 5131–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.P.; Shan, M.J.; Zeng, J. Parallel batch processing machine scheduling under two-dimensional bin-packing constraints. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2023, 72, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.W.; Lu, L.F.; Zhong, X.L. Parallel-batch scheduling with rejection: Structural properties and approximation algorithms. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 310, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunoglu, A.; Gahm, C.; Wahl, S.; Tuma, A. Learning-augmented heuristics for scheduling parallel serial-batch processing machines. Comput. Oper. Res. 2023, 151, 106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukkoc, I.; Keskin, G.A.; Karaoglan, A.D.; Karadag, S. A hybrid discrete differential evolution-genetic algorithm approach with a new batch formation mechanism for parallel batch scheduling considering batch delivery. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 460–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jula, P.; Leachman, R.C. Coordinated multistage scheduling of parallel batch-processing machines under multiresource constraints. Oper. Res. 2010, 58, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Chen, H.P.; Du, B.; Tan, Q. Heuristics to schedule uniform parallel batch processing machines with dynamic job arrivals. Int. J. Comput. Integ. Manuf. 2013, 26, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Chen, H.P.; Li, X.P. A bi-objective scheduling problem on batch machines via a Pareto-based ant colony system. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 145, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, M.; Seidgar, H.; Fazlollahtabar, H.; Bijani, R. Bi-objective optimisation for scheduling the identical parallel batch-processing machines with arbitrary job sizes, unequal job release times and capacity limits. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 1680–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.C.; Liu, M.; Chen, H.P.; Li, X.P. An effective discrete differential evolution algorithm for scheduling uniform parallel batch processing machines with non-identical capacities and arbitrary job sizes. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 179, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.H.; Yan, J.H.; Leung, J.Y.T.; Li, K.; Chen, H.P. Ant colony optimization algorithm for scheduling jobs with fuzzy processing times on parallel batch machines with different capacities. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 75, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.H.; Huo, S.Y.; Li, K.; Chen, H.P. Integrated scheduling on parallel batch processing machines with non-identical capacities. Eng. Optim. 2020, 52, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Wang, F.; Gupta, J.N.D.; Chung, T. Scheduling identical parallel batch processing machines involving incompatible families with different job sizes and capacity constraints. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, H.; Chu, C.B.; Jia, Z.H.; Chen, J.F. A bi-objective evolutionary algorithm scheduled on uniform parallel batch processing machines. Exp. Syst. Appl. 2022, 204, 117487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chu, F.; He, J.K.; Yang, D.P.; Chu, C.B. Coke production scheduling problem: A parallel machine scheduling with batch preprocessings and location-dependent processing times. Comput. Oper. Res. 2019, 104, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulett, M.; Damodaran, P.; Amouie, M. Scheduling non-identical parallel batch processing machines to minimize total weighted tardiness using particle swarm optimization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 113, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jia, Z.H.; Li, K. Scheduling parallel-batching processing machines problem with learning and deterioration effect in fuzzy environment. J. Intel. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 40, 12111–12124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chang, P.C.; Song, S.J.; Wu, C. A multi-objective artificial bee colony algorithm for parallel batch-processing machine scheduling in fabric dyeing processes. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 116, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.M.; Dai, T. An adaptive shuffled frog-leaping algorithm for parallel batch processing machines scheduling with machine eligibility in fabric dyeing process. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 7704–7721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, D.B.; Tang, H.T.; Li, X.X.; Lei, D.M. A dynamical teaching-learning-based optimization algorithm for fuzzy energy-efficient parallel batch processing machines scheduling in fabric dyeing process. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 167, 112413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi-Zadeh, B.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Taheri-Moghadam, A.; Rastgar, I. Solving a bi-objective unrelated parallel batch processing machines scheduling problem: A comparison study. Comput. Oper. Res. 2017, 88, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.J.; Liu, X.B.; Pei, J.; Thai, M.T.; Pardalos, P.M. A hybrid ABC-TS algorithm for the unrelated parallel-batching machines scheduling problem with deteriorating jobs and maintenance activity. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 66, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.C.; Xie, J.H.; Du, N.; Pang, Y. A random-keys genetic algorithm for scheduling unrelated parallel batch processing machines with different capacities and arbitrary job sizes. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 334, 254–268. [Google Scholar]

- Sadati, A.; Moghaddam, R.T.; Naderi, B.; Mohammadi, M. A bi-objective model for a scheduling problem of unrelated parallel batch processing machines with fuzzy parameters by two fuzzy multi-objective meta-heuristics. Iran. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 16, 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zarook, Y.; Rezaeian, J.; Mahdavi, I.; Yaghini, M. Efficient algorithms to minimize makespan of the unrelated parallel batch-processing machines scheduling problem with unequal job ready times. PAIRO Oper. Res. 2021, 55, 1501–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, A.; Shahidi-Zadeh, B.; Niaki, S.T.A. Unrelated parallel batch processing machine scheduling for production systems under carbon reduction policies: NSGA-II and MOGWO metaheuristics. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 17063–17091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Wang, W.Z.; Deveci, M.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wu, X.Z.; Coffman, D. A novel carbon reduction engineering method-based deep Q-learning algorithm for energy-efficient scheduling on a single batch-processing machine in semiconductor manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 6449–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Ji, B.; Yu, S.S.; Wu, G.H. A tabu-based adaptive large neighborhood search for scheduling unrelated parallel batch processing machines with non-identical job sizes and dynamic job arrivals. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2024, 36, 409–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.X.; Che, Y.X.; Ng, T.S.; Deng, J. Unrelated parallel batch processing machine scheduling with time requirements and two-dimensional packing constraints. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 162, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, H.P. Multi-objective energy-aware batch scheduling using ant colony optimization algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 131, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, Z.H.; Li, K. A multi-objective co-evolutionary algorithm of scheduling on parallel non-identical batch machines. Exp. Syst. Appl. 2021, 167, 114145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.C.; Li, X.L.; Du, N.; Pang, Y.; Chen, H.P. A multi-objective differential evolution algorithm for parallel batch processing machine scheduling considering electricity consumption cost. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 96, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zheng, L. Scheduling unrelated parallel batch processing machines under time-of-use electricity prices. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 1631–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, H.; Chu, C.B.; Jia, Z.H.; Wang, Y. A bi-objective evolutionary algorithm for minimizing maximum lateness and total pollution cost on non-identical parallel batch processing machines. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 172, 108608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H.; Ma, R. A production plan considering parallel machines and deteriorating effects: Minimizing the makespan in the section of steel box girder processing. Neural Process. Lett. 2023, 33, 2340002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Lu, S.J.; Ren, M.Y.; Cheng, H.; Liu, X.B. Modified benders decomposition and metaheuristics for multi-machine parallel-batch scheduling and resource allocation under deterioration effect. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 108977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorn, D.S.; Monch, L. Learning priority indices for energy-aware scheduling of jobs on batch processing machines. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2024, 37, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, M.; Chiong, R.; Noman, N.; Liao, X.Y.; Li, D.B. A metaheuristic framework for energy-intensive industries with batch processing machines. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 4502–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.X.; Qiao, F.; Jiang, S.X.; Zhu, H.B.; Wang, J.K. Deterioration-Aware Collaborative Energy-Efficient Batch Scheduling and Maintenance for Unrelated Parallel Machines Based on Improved MOEA/D. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 2056–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudek, R. A fast local search for the identical parallel machine scheduling problem with the position-based deteriorating effect and maintenance. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Wang, F.; Gupta, J.N.D.; Chung, T.P. Scheduling identical parallel machines involving flexible maintenance activities. Exp. Syst. Appl. 2025, 263, 125722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, P.; Xiang, W.B.; Jin, M.Y.; Li, H.S. Generative deep reinforcement learning method for dynamic parallel machines scheduling with adaptive maintenance activities. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 77, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Khaled, A.A. A survey on the imperialist competitive algorithm metaheuristic: Implementation in engineering domain and directions for future research. Appl. Soft Comput. 2014, 24, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasi, M.; Selcuk, Y.S.; Özener, Ö.; Coban, E. Imperialist competitive algorithm for unrelated parallel machine scheduling with sequence-and-machine-dependent setups and compatibility and workload constraints. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 190, 110086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Yang, Z.P.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.T.; Sun, L.B.; Guo, S.S. A hybrid imperialist competitive algorithm for energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling problem with variable-size sublots. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 172, 108641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lei, D.M. An imperialist competitive algorithm with feedback for energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling with transportation and sequence-dependent setup times. Eng. Appl. Arti. Intel. 2021, 103, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.R.; Li, J.Q.; Huang, T.H.; Duan, P. Discrete imperialist competitive algorithm for the resource-constrained hybrid flowshop problem with energy consumption. Complex Intel. Syst. 2021, 7, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lei, D.M.; Cai, J.C. Two-level imperialist competitive algorithm for energy-efficient hybrid flow shop scheduling problem with relative importance of objectives. Swarm Evolu. Comput. 2019, 49, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidgar, H.; Kiani, M.; Abedi, M.; Fazlollahtabar, H.S. An efficient imperialist competitive algorithm for scheduling in the two-stage assembly flow shop problem. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 1240–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE. Trans. Evolut. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L. Multi objective evolutionary algorithms: A comparative case study and the strength Pareto approach. IEEE. Trans. Evolut. Comput. 1999, 3, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.M. Pareto archive particle swarm optimization for multi-objective fuzzy job shop scheduling problems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 37, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, P.A.N.; Thierens, D. The balance between proximity and diversity in multiobjective evolutionary algorithms. IEEE. Trans. Evolut. Comput. 2003, 7, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, G. Introduction to Quality Engineering, Asian Productivity Organization; Asian Productivity Organization: Tokyo, Japan, 1986. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).