1. Introduction

Known quantisation procedures usually start with a classical theory and proceed to its quantum version by promoting relevant physical quantities to operators obeying a non-commutative algebra. In electromagnetism, in order to maintain locality of interactions, it is necessary to carry out quantisation by using the electromagnetic (EM) potentials, expressed in a gauge that can be chosen according to various criteria. The Lorenz gauge, in particular, is representative of a class of gauges that are explicitly Lorentz-covariant. The price to pay for Lorentz covariance is the appearance of the so-called “ghost modes” (one longitudinal and one scalar). They are called “ghosts” because they are considered unobservable dynamical variables that need to be removed by means of imposing extra conditions to recover the space of physically relevant observables, which in the case of electromagnetism are the transverse modes. This is performed via the “Gupta–Bleuler” condition—see our previous work [

1] and references [

2,

3,

4]. We note here that this construction is a standard textbook technique and that it respects the Lorentz symmetry.

Conventionally, in standard quantum electrodynamics (QED)), it is thought that the physically relevant modes are those that are gauge-invariant. In particular, transverse modes of the potentials are the only gauge-invariant modes, which are present in all gauges and hence are traditionally used to define the space of physically observable states. The other modes, in the standard treatments, are considered as dressing the naked charges, and only the dressed charges are considered as observable, not the naked charges alone. Some have expressed dissatisfaction with the existence of ghost modes, as they appear to be redundant, while others have argued that they are physical and they are necessary to have a fully local, relativistically compliant account of electromagnetism with sources, see, e.g., [

5,

6,

7].

In this paper we explore the consequences of relaxing the traditional assumption that naked charges cannot be treated as independent subsystems. Once this assumption is relaxed, we uncover a remarkable effect, suggesting that ghost modes are not physically irrelevant as usually thought. Hereinafter, therefore, when we mention “charge(s)” we shall mean “naked charges”: the criterion for a charge to be “naked” is that it can be treated as an independent subsystem from the field’s modes, so that an operation acting only on the charge’s degrees of freedom cannot instantaneously change the field and vice versa. We shall then explain that in the Coulomb interaction of a quantised charge with the EM potentials expressed in the Lorenz gauge, the charge and the EM field are entangled and that this entanglement is, in fact, observable. Specifically, we suggest an interference experiment involving a charge superposed across two locations, which uses quantum state tomography to detect this entanglement. This experiment amounts to (indirectly) detecting the scalar ghost modes. We say that the detection is “indirect” because it does not correspond to detecting single photons associated with such modes. Nonetheless, this entanglement is an (at least in principle) observable effect, and while it is predicted in the Lorenz gauge, it is not predicted in other gauges (such as the Coulomb gauge) as traditionally quantised, where such modes do not exist. This is so unless, of course, one acknowledges the quantum nature of all four modes in all gauges but then proceeds to define different constraints that would correspond to different gauges. We note that the spirit of our conclusion is similar to other analyses about ghost modes emerging in other gauges, such as the longitudinal modes in the temporal gauge [

8,

9]; such modes have been analysed in cavity QED, see, e.g., [

10].

The possibility of performing open-loop interferometry, as discussed in this paper, has so far been unnoticed since, to predict it, one needs to go beyond standard procedures such as the S-matrix methods, see, e.g., [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. This is because the S-matrix formalism relates asymptotic “in” and “out” states, which correspond to free particles long before and after an interaction took place; in contrast, our experiment probes the entangled state of the system during the interaction, without letting it evolve to an asymptotic future. The quantity that we propose to measure is not a scattering amplitude, as traditionally conceived in quantum field theory or QED (see, e.g., [

16]). Our experimental scheme uses open-loop interferometry on the charge, which, as we shall explain, is different from traditional closed-loop interferometry. Therefore, our proposed experiment cannot be described in terms of the free input and output fields, as is normally performed in quantum field theory.

We shall also adopt the following informal definition of a “real” physical variable: a degree of freedom of a system is “real” if, through that degree of freedom, the system can become entangled with a probe in such a way that the entanglement can be detected by a suitable measurement on the probe. Note that such a measurement need not directly involve the degree of freedom in question.

2. Ghost Entanglement: Informal Description

In any gauge, one can always represent the quantised modes of the free field via a set of simple quantum harmonic oscillators, one per each degree of freedom (or mode). In the ground state, the dispersion in x is proportional to , where is the frequency of the mode. The x and p variables are simply the quadratures of the field. When a charge is introduced, each of the modes responds because the presence of the charge acts as a perturbation. In the static regime, the scalar modes of the electromagnetic field, as described in the Lorenz gauge, hence become a collection of driven harmonic oscillators, with the driving term equal to , where q is the coupling strength. This results in the ground state of the oscillators being displaced to a coherent state. The displacement in the position becomes . The amplitude of this coherent state is , and therefore it has photons on average. This approximates, in the limit where is large or q is small, the probability that the new ground state of the driven field mode will result in the excited state of the free field (without interactions).

These states of scalar photons are considered virtual and undetectable because they do not contain any transverse photons; nonetheless, they are necessary to give a local, causal and Lorentz-covariant account of the Coulomb interaction between static sources. Following this account, when a charge is in a superposition of two different positions, each of the positions generates its own set of coherent states (whose amplitude peaks at the location of the charge). In other words, the charge and the scalar modes of the field become (at least formally) entangled. The amount of entanglement can be computed exactly (as we will show below), and it is equal to the total number of scalar photons , where is the fine structure constant.

This integral is logarithmically divergent (the notorious “infrared catastrophe”); however, with reasonable cut-offs it can be argued that it is on the order of unity (with logarithmic corrections as a function of the extent of the superposition). The amount of entanglement between the charge and the field is therefore very closely approximated by the fine structure constant. It is for this reason that, when the charge is bigger than the inverse of the fine structure constant times the electron charge, the entanglement with the scalar modes becomes close to unity, thereby significantly decohering the superposition of the charge. Note that here we are using as a measure of entanglement the degree of mixedness of the state in question, assuming that the overall state of the two charges plus the field is initially a pure state. This correspond to the linear entropy [

17]. However, the exact measure of entanglement does not matter here (all good measures are known to satisfy the property that if one of them shows a non-zero amount of entanglement, the others should too). Indeed, here we provide a qualitative analysis: we point out that there is some degree of entanglement with the field, and that it is in principle measurable.

Hereinafter we shall treat the charges non-relativistically. This is because they are considered to be (nearly) stationary. Formally it also means that there will be an energy cut-off of and that no field modes within the radius equal to the Compton wavelength of the electron will be included in the analysis. This is not an important omission since the relativistic effects neglected here would represent a small correction to the value we estimated.

The crucial question now is as follows: can this field–matter entanglement (as formally predicted in the Lorenz gauge) be detected? Naively, one might think that this entanglement cannot be detected. First of all, the photons are associated with the “ghost” modes (the scalar modes in the Lorenz gauge) and should therefore not be capable of generating “clicks” in photodetectors (only the excitations of the transverse modes make clicks). In other words, the scalar modes do not contain free photons: in a dynamical situation scalar and longitudinal photons always cancel out, which is (as we shall discuss) the Gupta–Bleuler condition. In addition, the entanglement between the charge and the field should lead to what is known as “fake” (false) decoherence. This means that, although normally entanglement between a system (in this case the charge) and its environment (in this case the scalar modes) should lead to a decrease in the interference fringes (and hence decoherence), here, when the charge is interfered, the two sets of coherent states (each generated in the two branches of the charge’s quantum state) become one and the same state because the two spatial states of the charge are rejoined at the point of interference. Therefore, in a single-charge (and “closed-loop”) interference experiment, the charge entanglement with the scalar modes is simply undetectable since it does not affect the (closed-loop) interference. It is our opinion that all the charge interference experiments so far have always been of this kind, which is why the scalar mode entanglement has remained unnoticed.

The above arguments are sound, and yet we believe that the field–matter entanglement can be detected (under the assumption that naked charges are independent subsystems, see the discussion in the Conclusions). This is because the arguments apply to what one may call a “closed-loop” interference on the charge. It is possible, however, to measure the charge–field entanglement without closing the interferometric loop of the charge, using a standard technique of quantum metrology, called quantum state tomography. We discussed this very experimental setup in our analysis of the locality of the Aharonov–Bohm effect [

18]—in that paper, the aim was to reconstruct the relative phase of a probe charge that is moving in a superposition of two paths around a fixed solenoid, before the charge closes the interference loop. Here, we shall instead have a probe charge moving in the potential generated by another, fixed, charge; the aim is to measure the amount of entanglement between the probe charge and the EM field. In both cases, to detect the relevant phases along the paths, one needs an additional charge, a reference, which is superposed across two locations, like the probe; we use this method to perform a tomographic reconstruction of the probe’s state using local measurements on each path and by using the second charge as a reference. The quantum state of the probe is predicted to be mixed due to the entanglement with the field. Hence this is a way to indirectly confirm entanglement between the probe charge and the field (assuming no other decoherence is at play). The choice of a bosonic charged particle is for simplicity of exposition, in that it is not affected by the fermionic superselection rule. However one could use a fermionic particle, as the use of a reference allows one to measure only observables that commute with the fermionic parity operator—as described in our work on the Aharonov–Bohm effect [

18].

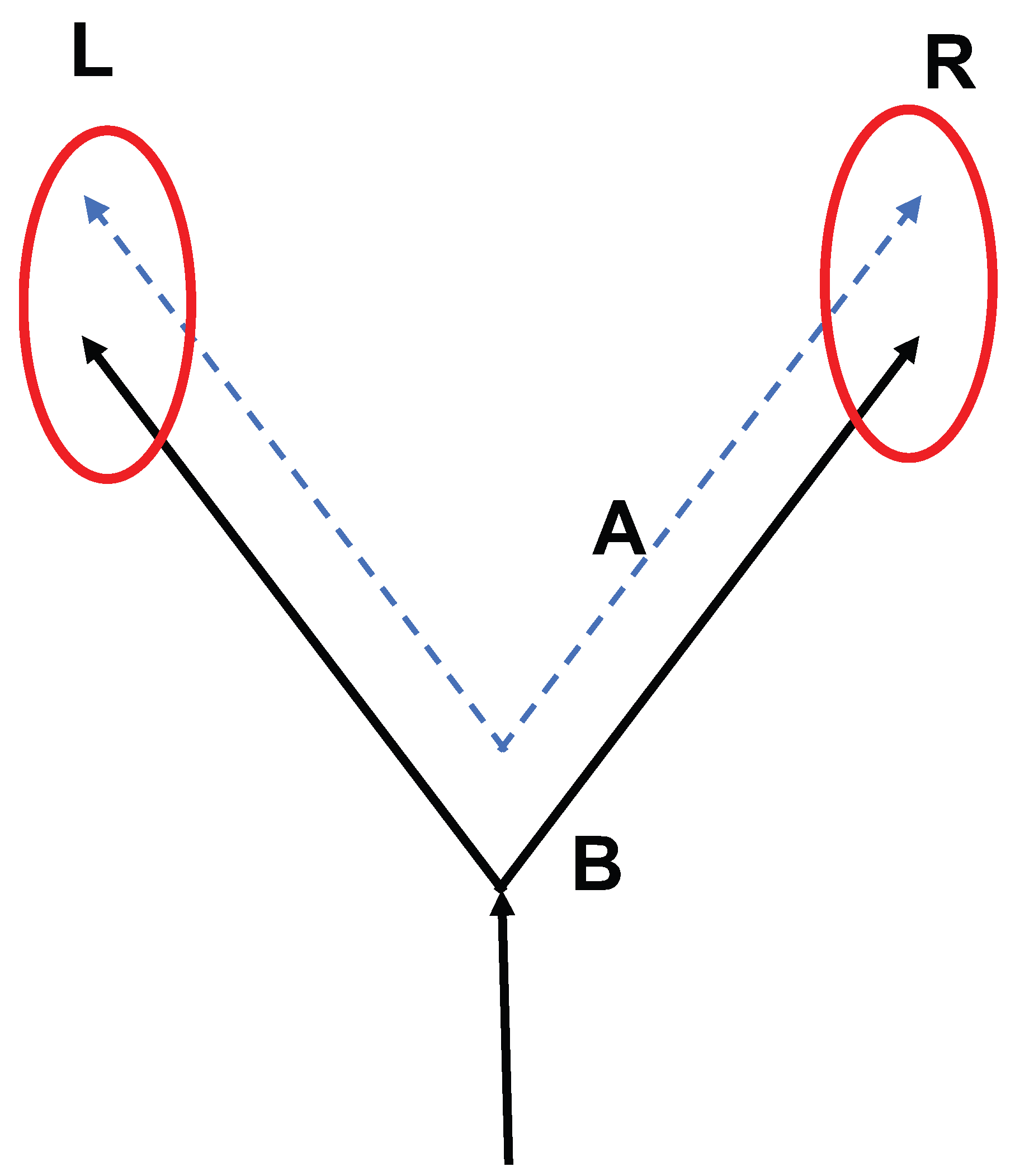

For convenience, let us divide the space where the interference takes place into two regions, labelled “left” and “right”, with respect to the line that cuts the interferometer into two symmetric halves (see

Figure 1). We shall focus here only on the probe (charge “A”) and the reference (charge “B”). We shall not explicitly refer to the third fixed charge generating the Coulomb field that induces a phase on the probe.

Suppose that charge A (probe) is at locations and and charge B (reference) is at locations and . We then have four spatial configurations of charges, , each entangled with a different corresponding set of scalar modes .

By making suitable local measurements with respect to the partition left/right on both charges, we can obtain the off-diagonal element in the subspace where there is only one charge in modes

and

and only one charge in modes

and

. This element contains a pure phase, which is due to the Coulomb interaction, and a real amplitude, which represents the entanglement with the scalar modes. It is this real amplitude that is equal to

and effectively shows that the scalar photons should be considered as “real” as the transverse ones (although they do not propagate at the speed of light and are always linked to the charge). We proceed to discuss the details of this scheme in the remaining part of this paper, which are based on textbook treatments of the topic (e.g., [

2]).

It is also important to notice that charges A and B need to be distinguishable. Each charge is prepared in a state that corresponds to a sharp state of an internal degree of freedom (e.g., spin)—this state is represented by the label A or B. Then each charge is prepared in a superposition of two different locations (R or L); each corresponds to a well-defined area of space where each charge can be prepared independently of the other. If the two charges could not be distinguished, the protocol to measure the phase would not work, as it would not be possible to measure the relevant correlations across the partition L/R. Now, the preparation of a superposition of a single charge across two different locations (R and L) is not affected by the superselection rule for charge, as the total charge remains unchanged throughout the process (there is exactly one charge in total before and after the preparation of the superposition).

3. Measuring Ghost Entanglement with Open-Loop Tomography

Here we shall describe at the general, abstract level the experimental scheme to measure the ghost entanglement. How to realise this experiment in detail is an interesting open question, which depends on the particular system chosen to probe the effect—we leave this investigation and a feasibility study to future work. Let

,

be bosonic creation/annihilation operators for charge

A to be in a spatial mode

on the left and

,

be bosonic creation/annihilation operators for charge

A to be in a spatial mode

on the right, and similarly for charge

B. For instance, the state where charge A is superposed across two locations is

, where

is the bosonic vacuum. When charge

A is prepared in a superposition of the left and right path, the charge–field Hamiltonian will induce the state

, where the Coulomb phase

, as computed in [

1], is a function of the points

across which the charge is superposed. Note that the non-zero phase difference is due to the presence of the Coulomb field of another, stationary charge (additional to the reference charge).

Measuring the degree of entanglement between charge

A and the field directly by local tomography on charge

A is impossible: in this case the charge superselection rules impede measurements of observables such as

(for this would entail creating a charge out of the vacuum locally to spatial mode “L”). However, as pointed out in [

18], the degree of entanglement can still be reconstructed by utilising another reference charge and local tomography (on the left and right sides) involving the same number of charges, without violating any superselection rule. This is an effective way of measuring the phase without closing the interferometer loop coherently—i.e., with only decoherent communication between the two sides.

To implement this procedure, we follow the protocol described in [

18], represented in

Figure 1. Consider the state where two charges,

A and

B, are each superposed across the left and right regions:

where

is the Coulomb phase relative to the configuration of charges

, as computed in [

1]. One can group the terms relative to the left and to the right modes as follows:

In the branches where only one charge is present on the left and right arms (second line of the above equation), the degree of entanglement with the field can be detected by measuring, locally on the left and on the right, the quantum observable

: if there were no entanglement with the field, for the above state this observable would be sharp, with value 1 in the subspace where only one charge is on the left and one on the right. Note that in this protocol, the two-charge measurement of

circumvents the charge superselection rule by preserving the charge number in both the L and R regions. Consequently, the constraint operator of the Gupta–Bleuler condition [

2] commutes with

because it is a function of the charge number operator only. According to standard QED that operator would not represent an observable because it contains only the naked charge’s operators, which are supposed to be unobservable (only dressed charges are observable). Here we shall continue the reasoning assuming that instead naked charges can be measured and explore the consequences of this possibility.

Due to the entanglement with the EM field, as prescribed by the Gupta–Bleuler condition [

2], the expected value of this observable is not 1, but it is attenuated by the overlap of the coherent states of the field in that subspace,

, whose value can be calculated formally from the definitions given in [

1]. The main idea utilised in the appendix is to use the description of the charge–field interaction in the Lorenz gauge, together with the supplementary conditions that define this gauge and the allowed physical states, to calculate the states of the field corresponding to there being the particular charge distribution corresponding to each branch of the superposition of the test charge. We stress that the Gupta–Bleuler formalism is one of a number possible approaches to quantisation in the Lorenz gauge. Our conclusions are not dependent on this formalism. We also note that the formalism preserves Lorentz covariance; in fact its main features ensue from the Lorentz covariance constraint.

For generic locations

and

of the two charges, one has

where we have introduced the coupling constant

(whose dimensions are those of energy). By integrating in

, we see that this is a (logarithmically) divergent integral, as expected since we are working with point-like charges. It is therefore meaningful to introduce a lower and an upper cut-off, in which case we find that the integral is proportional to the fine structure constant times

, where

is some minimum spatial extension (corresponding to the upper momentum cut-off) and

is the extent of the superposition (corresponding to the lower momentum cut-off). We thus see that the dependence on the extent of the superposition is only logarithmic and therefore dominated by the fine structure constant. It is important to notice that one would have to carefully recalculate the effect with a different choice of cut-off parameters. Here it seems meaningful to assume that

is given by the Compton wavelength of the electron, since, as we explained, our treatment of the electron is non-relativistic. But, because of the logarithmic dependence, this choice will not affect the outcome a great deal anyway (another possible choice is, of course, the size of the spatial resolution of the detector).

Measuring by local measurements does not violate charge conservation superselection rule, as it can be performed by resorting to local observables (with respect to the partition left/right) that include the same charge number. By local tomographic reconstruction of the one-particle sector of the above state, one can therefore notice this reduction in visibility at any point along the path, without closing the interferometer coherently. Note, again, that it is crucial not to close the loop of the interferometer. Indeed, if one did that, the entanglement would vanish due to the fact that recombining the paths of the charge effectively erases the which-path information stored in the field (this is also known as the “fake decoherence” effect). We note that various sources of decoherence may hinder this effect. A full feasibility study to perform this experiment is important to plan the actual experiment, but such a feasibility study will depend on the particular configuration chosen and goes beyond the scope of this article; we leave this analysis for future work. We also note that this should involve a model of the detector, given that any detector will consist of charges too. However, we believe that the charge–field entanglement we propose to measure here should not affect the detector charges because they are, to a high degree of approximation, well localised.

Our conclusions would be applicable to the linearised quantum gravity in the corresponding gauge to Lorenz, also called the “De Donder” gauge, where the calculation is more complicated but the logic is essentially the same [

3,

4]. The difference would be the magnitude of the entanglement, which would be present, but (unlike in this case) more difficult to observe. In fact, we previously showed that the gravitational entanglement with a mass

m scales as

, where

is Planck’s mass [

19]. It is, therefore, natural to suppose that the electromagnetic entanglement with the charge will scale as

, where

is the Planck charge. If

Q is the electron charge

, then

, which is our result to the lowest order. So, in the same way that the entanglement with the field would prevent us from observing locally a charge superposition beyond a certain limit, the same would be true gravitationally, where the limit would be then given by the Planck mass of the object.

4. Conclusions

We have demonstrated that, by following standard quantisation procedures for the EM field in the Lorenz gauge, and assuming that naked charges can be observed independently of the field, the scalar modes of the EM field are entangled with any superposed charge. We have also discussed a possible experiment to detect this entanglement. It is interesting that in the derivation, we discussed the fact that the entanglement is induced by the Gupta–Bleuler condition [

2] in the presence of static sources and by the possibility of superposing charges across different spatial regions. The results in this paper are closely related to the results in references [

19,

20,

21], where it is discussed how the ghost modes of the gravitational field can mediate entanglement between two quantum probes. The relation between this work and those results is explained in a companion paper [

1], where we have analysed the relation between the gravitationally induced entanglement of references [

19,

20,

21] and the detectability of ghost modes. In particular, using the analogy between the EM quantised field and the linear quantum gravity approach, we analyse how the ghost modes of the EM field lead to measurable entanglement between two charges. Our results in the present paper are also closely related to the scheme we devised in [

18] in order to detect the Aharonov–Bohm phase with open-loop interferometry (see also the recent analysis by Kang on this topic [

22]). In that scheme it is once more the ghost modes of the EM field that are relevant to explain the generation of the Aharonov–Bohm phase locally and dynamically.

This analysis leaves us with a few possible scenarios: (1) The entanglement with the ghost modes is not observable: this could be because bare charges do not exist on their own but need always to be dressed by the ghost modes of the field, as suggested by standard QED [

2,

16], or because of some extra effect that we have not taken into account in this calculation, or because quantum field theory needs corrections. Conversely, if the entanglement is observable, the following are possible: (2) Physical ghost modes (such as the scalar modes in the Lorenz gauge, which propagate causally) are in fact observable and only predicted in some gauges; hence gauge invariance must be understood as valid only in some classical limit but violated in the quantum case. (3) All modes must be quantised in all gauges; however, the price to pay is that the resulting entanglement may not satisfy the standard observability requirements provided by the gauge-defining conditions (see the discussion in the Conclusions). (4) The quantisation scheme for the EM field as currently known is invalid (as it breaks gauge invariance), so one needs to look for alternative ways to construct a quantum theory of fields, where the entities that are currently called “ghost modes” are in fact valid observables. The options (2), (3) and (4), where the entanglement is observable, would be a major departure from standard QED as currently tested (see, e.g., [

23]), as we now briefly discuss.

Scenario (1), corresponding to standard QED, is that it is incorrect to consider the charge and the field as independent subsystems. While formally they may be described by commuting operators, charges and fields do not exist independently of one another; hence the entanglement in question may be unobservable after all. According to this view, real charges would correspond not to the bare (mathematical) charges but to the bare charges dressed with the scalar photons. Neither the bare charges nor the scalar photons can ever exist on their own. In this sense, the operator we claimed we were measuring in our open-loop experiment would already contain dressed operators; hence there would be no attenuation predicted on the dressed charges. The whole procedure of dressing is akin to mass renormalisation and it would lead us to conclude that the Coulomb gauge and the Lorenz gauge are in agreement after all because here no gauge predicts any entanglement. This dressed-charge view is already well-established in some quantum field theory circles in regard to static fields; however, we think that the predicted attenuation we discuss would add to the volume of arguments supporting it (to our knowledge, the idea of dressed charges has not been motivated this way before). Moreover, this view is usually applied to static configuration of charges, whereas the effect considered here is dynamical.

Scenario (2) is that the effect we discussed is observable and gauge invariance is broken—it is only meaningful in the classical limit but not in a quantum theory of electromagnetism that allows charges to exist in superpositions. This seems to be corroborated if we consider straightforward methods of quantisation in the cases of a few special gauges. For instance, in the Coulomb gauge, adopting standard quantisation procedures that only quantise transverse modes [

2], this entanglement does not exist. This is because the scalar and longitudinal modes are not quantised; hence there cannot be any entanglement between the field in those modes and the charges. In the temporal gauge one can find some degree of entanglement, but it is with the longitudinal modes of the vector potential, as outlined in [

8]. These modes are not considered physical either (because they propagate at a speed that is lower than the speed of light), but they would appear to generate a non-zero degree of entanglement that is different to that due to the scalar modes in the Lorenz gauge. Generalising, this suggests that detecting the entanglement predicted in this work would allow one to discriminate between the Lorenz gauges and other gauges. These considerations therefore suggest that in this scenario the current quantised theory of the EM field violates gauge invariance, which may only be valid in the classical limit. This could imply (as some authors have argued) that the photon mass is non-zero, see, e.g., [

22], and that it could be related to the degree of entanglement with the charge.

One possible way out, still assuming that the entanglement is observable, (scenario 3), is of course to always quantise either the longitudinal and/or the scalar modes in all gauges, as recommended in some accounts of quantum field theory (see, e.g., [

16,

24,

25]). For instance, in the Coulomb gauge the scalar potential is instantaneous but can be written as an operator

. In this case the detectability of entanglement would mean that the interpretation of the gauge-defining conditions, and of the so-called ghost modes, should be modified to make them into fully physical degrees of freedom even in gauges other than Lorenz. As is well known, even though some potentials in gauges other than Lorenz violate microcausality, this is not a problem because all the observable physical effects always rely on all the components in the form

. It is the overall effects of these components that constitute the observable entanglement in any particular gauge.

Finally (scenario 4) we can interpret these results to indicate that the quantised theory we have used is not the correct way to design a quantum theory of the electromagnetic field. This is an intriguing possibility, and it is supported by the fact that even the founding fathers of QED considered it an effective theory that one could use to perform calculations, to then be replaced by a full quantum theory of fields. What this theory might be is an open problem. One could speculate that only once a full quantum theory of spacetime is available will one be able to understand quantum fields on quantum spacetime (such as the EM field) properly and that those quantum theories will differ radically from the quantised theories we currently have.

These open questions will, as always, only be settled by a combination of new theory and novel experiments. The experiment we discussed is a first step to assessing the validity of some of these conjectures, and it is within direct reach of current technologies: we hope and expect that it will be performed as soon as possible in the near future.