1. Introduction

With the rapid development of the low-altitude economy and intelligent logistics, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have become core equipment in fields such as urban distribution and emergency rescue [

1,

2,

3]. As a key technology for UAV autonomous flight, path planning needs to generate optimal or near-optimal flight paths under the constraints of ensuring flight safety, energy limitations, and obstacle avoidance [

4,

5]. In complex urban environments, factors such as dense buildings and undulating terrain pose significant challenges to traditional path planning algorithms. However, swarm intelligence algorithms have emerged as a research focus in this field due to their efficient optimization capabilities [

6,

7,

8].

The Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) has been widely applied in UAV path planning, thanks to its advantages of simple structure, few parameters, and easy implementation [

9,

10]. Nevertheless, when addressing complex 3D path planning problems, the standard GWO exhibits inherent drawbacks, including slow initial convergence rate, deterioration of population diversity in the late stage, and proneness to falling into local optima [

11,

12]. These issues result in poor-quality planned paths, which face difficulties in meeting the requirements of practical applications. To overcome these challenges, scholars at home and abroad have conducted extensive improvement studies. The main strategies include introducing adaptive mechanisms [

13], using chaotic maps to optimize the initial population [

14], and hybridizing with other swarm intelligence algorithms (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization and Lion Swarm Optimization (LSO)) [

15,

16,

17]. While these studies have alleviated the premature convergence problem of GWO to a certain extent, they still suffer from limitations such as slow late-stage convergence and insufficient local exploitation capabilities. Thus, they still struggle to meet the high-precision and high-efficiency path planning requirements of UAV logistics distribution in complex urban environments [

18,

19].

Aiming to solve the shortcomings of existing studies, this paper proposes an improved Grey Wolf Optimizer (CPS-GWO) that integrates the Kent Chaotic Map with PSO. The main innovations are as follows:

Dual-dimensional optimization strategy: Combining the ergodicity of the Kent Chaotic Map and the cooperation mechanism of PSO to optimize population initialization and search strategy, respectively, thereby balancing initial population diversity and global optimization capabilities.

Nonlinear parameter adjustment: Designing a nonlinear adaptive control parameter to replace the traditional linear decay strategy and achieve dynamic balance between global exploration and local exploitation.

Multi-objective comprehensive cost function: Constructing a comprehensive objective function covering path length, collision penalty, height compliance, and smoothness to ensure the safety, efficiency, and feasibility of the path.

2. Fundamentals of Related Algorithms

2.1. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm achieves optimization by simulating the cooperative foraging behaviour of particle swarms [

20]. The update rules for particle velocity and position are expressed as shown in Equations (1) and (2) below:

Among them, and denote the velocity and position of the th particle at the th iteration, respectively; and represent the individual best position of the particle and the global best position of the population (at the th iteration), respectively; and are the individual learning factor and social learning factor of the particle, respectively; is the velocity inertia weight; and are random numbers within the range [0, 1].

2.2. Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)

The Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) is a heuristic optimization algorithm that simulates the hierarchical structure and hunting behaviour of grey wolf populations [

21]. The core of the algorithm lies in solving the optimal solution

, suboptimal solution

, third optimal solution

, and follower wolves

. The behaviour model of the algorithm is expressed as shown in Equations (3)–(10):

Among these, Equations (3)–(7) correspond to the prey encircling phase, where denotes the position of the prey at the th iteration; Equations (8)–(10) correspond to the prey hunting phase. Specifically, , , and represent the distances between the current grey wolfnd the wolf, wolf, and wolf, respectively; , , and denote the positions of the wolf, wolf, and wolf at the th iteration, respectively; and , are coefficient vectors; is the convergence factor; is the current number of iterations; and is the maximum number of iterations.

3. Design of Improved Grey Wolf Optimizer (CPS-GWO)

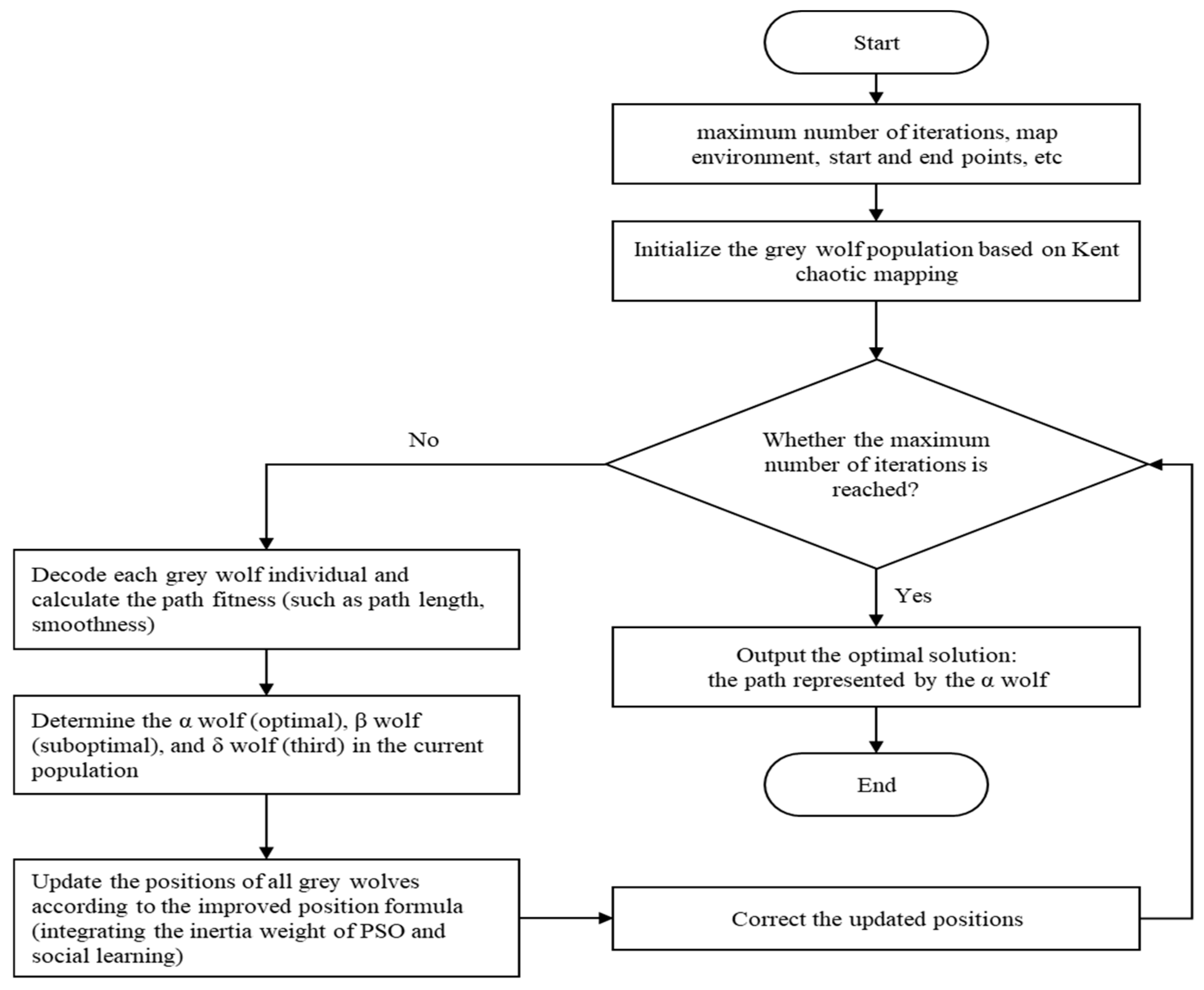

To overcome the premature convergence and limited local search ability of the standard grey wolf optimizer, this paper develops a chaotic PSO-enhanced grey wolf optimizer (CPS-GWO). CPS-GWO still follows the α–β–δ leadership hierarchy of the original GWO but redesigns the population evolution process from three complementary aspects. First, a Kent chaotic map is employed to initialize the population and to perform probabilistic chaotic perturbation during the iterations, so that the initial and intermediate solutions are more ergodically and symmetrically distributed in the search space, which enhances global exploration and helps the algorithm escape from local optima. Second, a nonlinear adaptive convergence factor is introduced to replace the traditional linear control parameter, allowing the algorithm to automatically adjust the balance between exploration and exploitation according to the iteration stage. Third, the inertia weight and social learning mechanism of PSO are embedded into the GWO position update rule, so that the search process can make fuller use of high-quality solutions while retaining the multi-leader guidance structure of GWO. By integrating chaotic exploration, nonlinear parameter control and PSO-inspired learning, CPS-GWO achieves faster convergence, stronger robustness and better optimization accuracy, and thus provides a more effective solver for the UAV logistics path planning problem considered in this study.

3.1. Population Initialization Based on Kent Chaotic Map

The traditional GWO generates the initial population randomly, which tends to result in uneven distribution. The Kent chaotic map exhibits excellent ergodicity and uniform distribution characteristics, and its mathematical model is expressed as shown in Equation (11):

By generating a chaotic sequence within the interval [0, 1] via the Kent chaotic map, and mapping this sequence to the UAV flight space after a normalization process, the initial grey wolf population is constructed—thereby enhancing population diversity and expanding the population’s coverage range in the search space.

3.2. Nonlinear Adaptive Control Parameter

The traditional linearly decaying parameter

cannot accurately match the complex search behaviour of grey wolves [

22,

23]. Therefore, a nonlinear adaptive strategy is introduced, as shown in Equation (12):

This strategy enables parameter to decrease slowly in the early stage of iteration, thereby enhancing the global exploration capability; in the later stage of iteration, it approaches 0 rapidly, focusing on local exploitation—ultimately achieving the dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation.

3.3. Position Update Rule Integrating PSO

To enhance the guidance of high-quality solutions and local search capability, the inertia weight and social learning mechanism of PSO are integrated [

24]. By embedding the PSO-inspired inertia weight and social learning term into the α, β, δ leadership structure of GWO and combining them with chaotic perturbation, CPS-GWO alleviates the classical premature convergence behaviour of PSO while preserving its fast convergence speed. The improved grey wolf position update rule is shown in Equation (13):

Among them,

denotes the individual best position of the

-th grey wolf;

,

, and

represent he global best, suboptimal, and third optimal positions, respectively;

,

, and

are dynamic weight coefficients, calculated as shown in Equation (14):

The inertia weight

, after an adaptive adjustment strategy is applied to it, is expressed as shown in Equation (15):

Among them,

and

;

represents the fitness value of the

-th grey wolf at the

-th iteration;

and

denote the population average fitness and minimum fitness at the

-th iteration, respectively. The flowchart of the improved CPS-GWO is shown in

Figure 1:

The pseudocode of the CPS-GWO algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1:

| Algorithm 1. The pseudocode of the CPS-GWO algorithm. |

| Input: Npop, Max_it, lb, ub, nD, fobj |

| Output: fvalbest, xposbest, Curve |

| 01: Parameter initialization using Kent chaotic mapping |

| 02: Calculate the fitness value of each population individual |

| 03: if t ≤ Max_it |

| 04: Parameter update |

| 05: if rand < CP |

| 06: Generate Kent chaotic sequence and perform chaotic perturbation on Xnew |

| 07: End If |

| 08: Boundary processing |

| 09: Update individual position |

| 10: End For |

| 11: Calculate the fitness values of all individuals after update |

| 12: Update parameters |

| 13: Record the optimal fitness of the current iteration |

| 14: t = t + 1 |

| 15: End While |

| 16: Output the optimal fitness |

3.4. Multi-Objective Comprehensive Cost Function

After comprehensively considering path length, collision penalty, smoothness, and height constraints, the problem model is constructed as shown in Equations (16)–(20) [

25,

26,

27]. Among them,

denotes the objective function,

represents the path length constraint;

is the weight coefficient of the collision constraint

;

is the weight coefficient of the smoothness constraint

; and

is the weight coefficient of the height constraint

.

where

represents the smoothness constraint. The smoothness index is defined as the sum of absolute turning angles across all consecutive path segments. A higher value indicates more frequent or abrupt directional changes, resulting in a less smooth trajectory. Trajectories with larger cumulative turning angles will incur higher cost values and be progressively eliminated during iterative optimization, thereby guiding the remaining solutions towards shorter and smoother paths.

Among these, is the number of waypoints; (, , ) are the 3D coordinates of the -th waypoint; denotes the distance between the -th waypoint and the obstacle; represents the safety threshold for the distance between the waypoint and the obstacle; is the height difference between the -th waypoint and the obstacle; denotes the height threshold for the waypoint relative to the obstacle; is the violation penalty value when a waypoint enters the obstacle’s safety range; is the vector angle formed by three consecutive waypoints; and is the violation penalty value when a waypoint enters the obstacle’s safe height range.

3.5. Algorithm Base Performance Validation

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed CPS-GWO, this study compares the CPS-GWO with the WOA, PSO, GWO, SSA and ACO using ten benchmark test functions as shown in

Table 1. Among them,

–

are unimodal test functions,

–

are multimodal test function, and

–

are fixed-dimension multimodal test functions. Each algorithm was run for 100 iterations. The average value and standard deviation of the results were used as evaluation metrics. Detailed test functions are listed in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 2, based on the comparison of mean values and standard deviations of the optimal search results, CPS-GWO exhibits slightly lower search precision than PSO only for the

test function. However, for the other test functions, the optimal and mean values obtained by CPS-GWO are smaller than those of the other algorithms. Moreover, CPS-GWO achieves theoretical optimal values in the

–

tests, demonstrating that the improved algorithm is more stable.

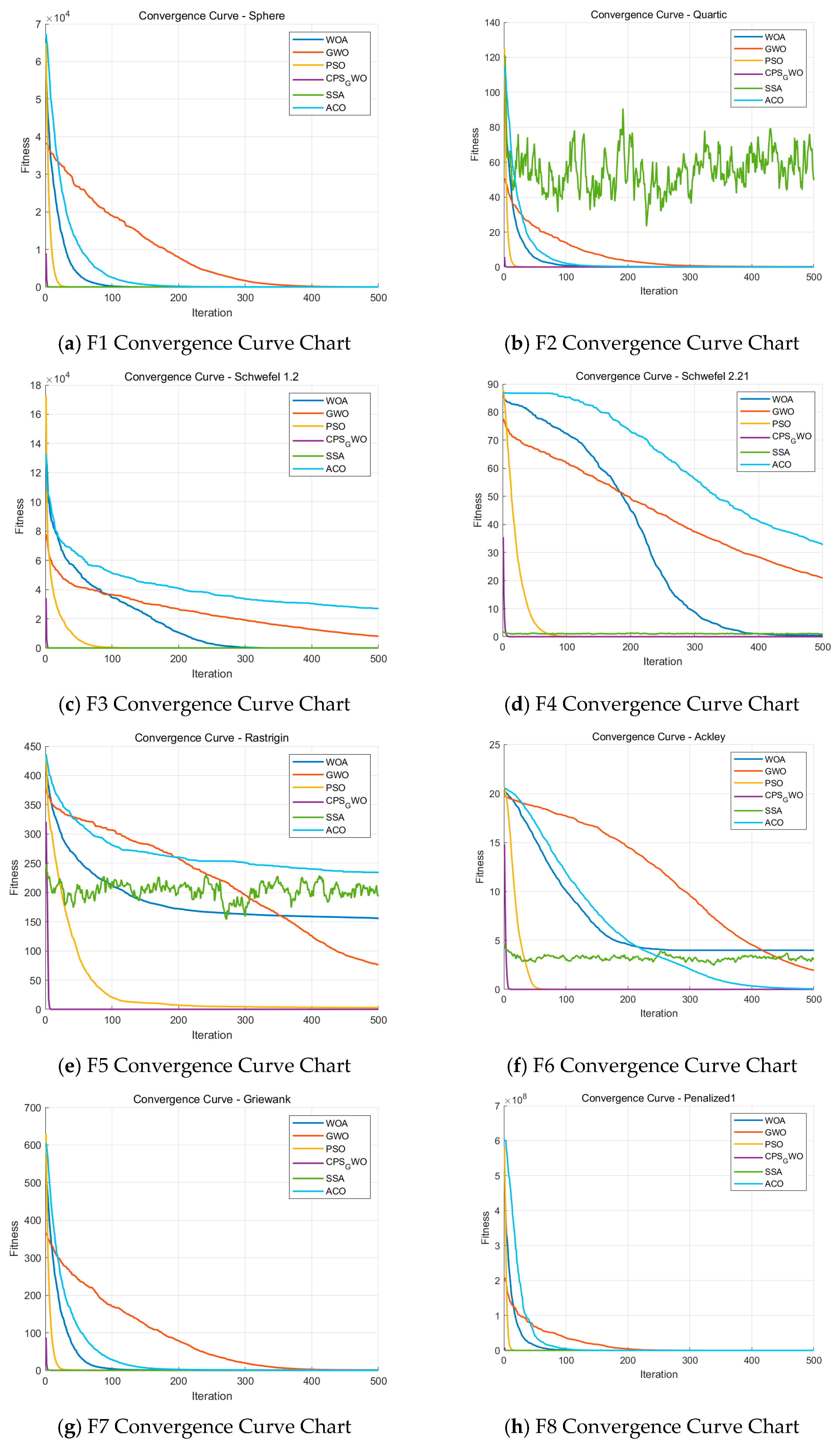

Table 2 shows that CPS-GWO reaches the theoretical optimal value in single-peak function and fixed-dimension multi-peak function with a lower standard deviation compared to traditional algorithms, which proves that it has stability and anti-local optimality in complex optimization problems and provides the algorithmic basis for UAV trajectory optimization. The convergence curves of the test functions are shown in

Figure 2.

The convergence curves of ten benchmark functions demonstrate that CPS-GWO exhibits superior optimization efficiency and stability across all tests. For four unimodal functions, CPS-GWO rapidly approaches zero with a steeper descent gradient, achieving or approximating the theoretical optimum within fewer iterations. For multi-modal and complex functions, CPS-GWO maintained continuous descent, ultimately converging to lower fitness values. Its oscillation amplitude was markedly smaller than that of the comparison algorithms, indicating enhanced global exploration capabilities alongside superior escape from local optima. Overall, CPS-GWO outperforms WOA, PSO, GWO, SSA, and ACO in convergence speed, final accuracy, and robustness, providing a more reliable algorithmic foundation for subsequent complex scenario optimization.

4. Simulation Experiments

4.1. Experimental Environment Setup

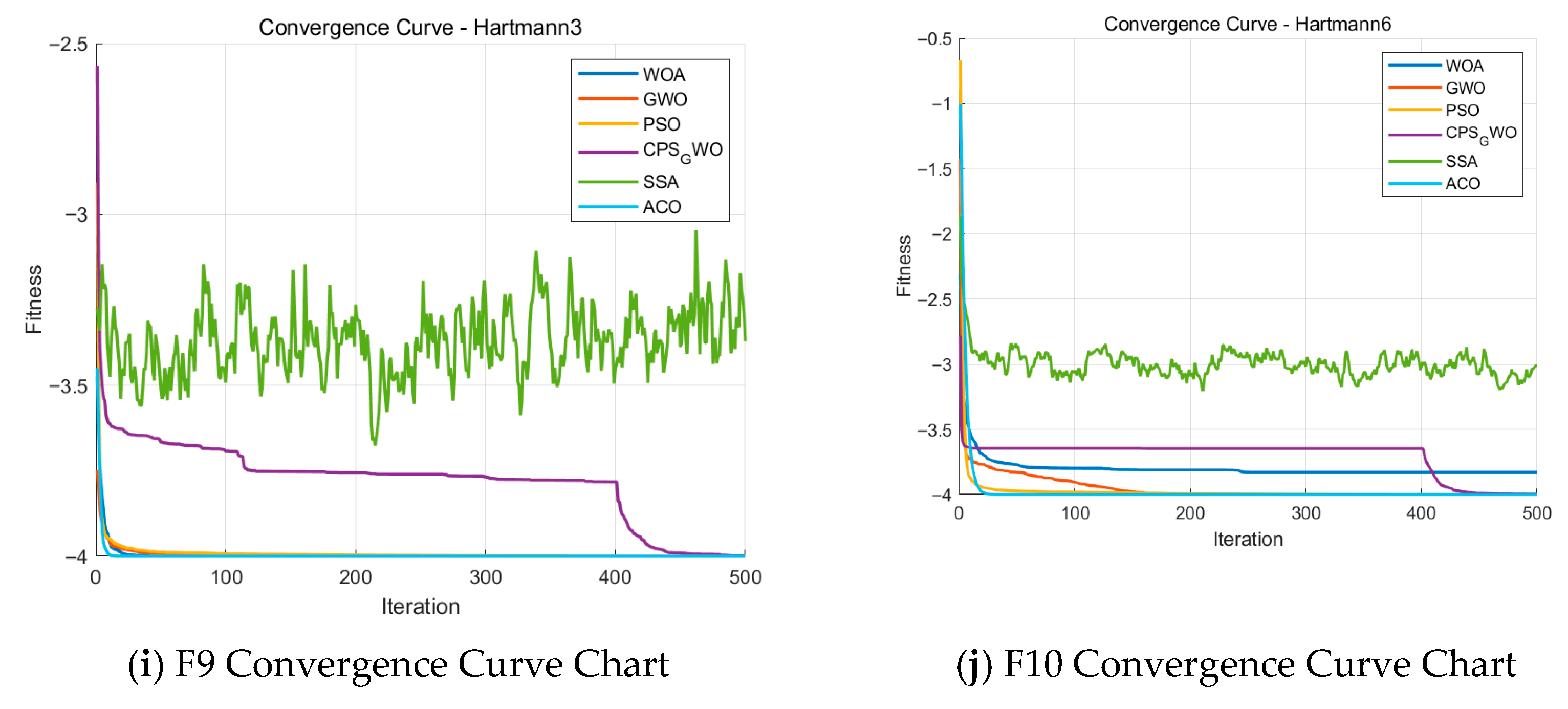

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the improved Grey Wolf Optimizer (CPS-GWO) in complex 3D UAV path planning, experiments were performed on a hardware platform equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7H (260 W), 16 GB RAM, and RTX 5060. Simulation experiments were carried out using the MATLAB R2022b platform, in which a 3D space was constructed. On this basis, the scenario includes two types of static obstacles: buildings and trees (as shown in

Figure 3).

In the constructed 3D environment, the units along the x-, y-, and z-axes are interpreted as metres, i.e., one coordinate unit corresponds to 1 m in real space. The horizontal range (0–100 in both x and y directions) and the altitude limits are selected to emulate a typical short-range UAV logistics route in an urban district. The resulting obstacle dimensions and planned trajectories can therefore be directly mapped to real-world distances and heights for pre-flight path planning applications.

Buildings in the figure are in the shape of rectangular prisms, while trees are in the shape of pyramids. A total of 7 static obstacles of the building type were set, and their detailed information is presented in

Table 3 below.

Thirty small tree-shaped obstacles were randomly generated, with the specifications that each obstacle has a base edge length of no more than 2 m, a height of no more than 6 m, and no less than 5 m from buildings.

To achieve a more intuitive distinction between threat areas, the start points, the end point, and the terrain in the simulated 3D environment scene, hereafter, static obstacles are represented by black solid models, while the start point and the end point are denoted by a green pentagon and a purple square, respectively.

4.2. Simulation Experiments and Result Analysis

In practical drone logistics operations, three-dimensional trajectories are typically generated on the ground prior to take-off and subsequently uploaded to the drone for execution. Consequently, the simulation case presented in this chapter represents a typical pre-flight planning scenario for urban logistics delivery tasks. In this experiment, the number of iterations was fixed at 500, and the population size was adjusted to analyze the impact of population size on the algorithm’s convergence speed and path quality. Each group of experiments was repeated 30 times, and the results were averaged.

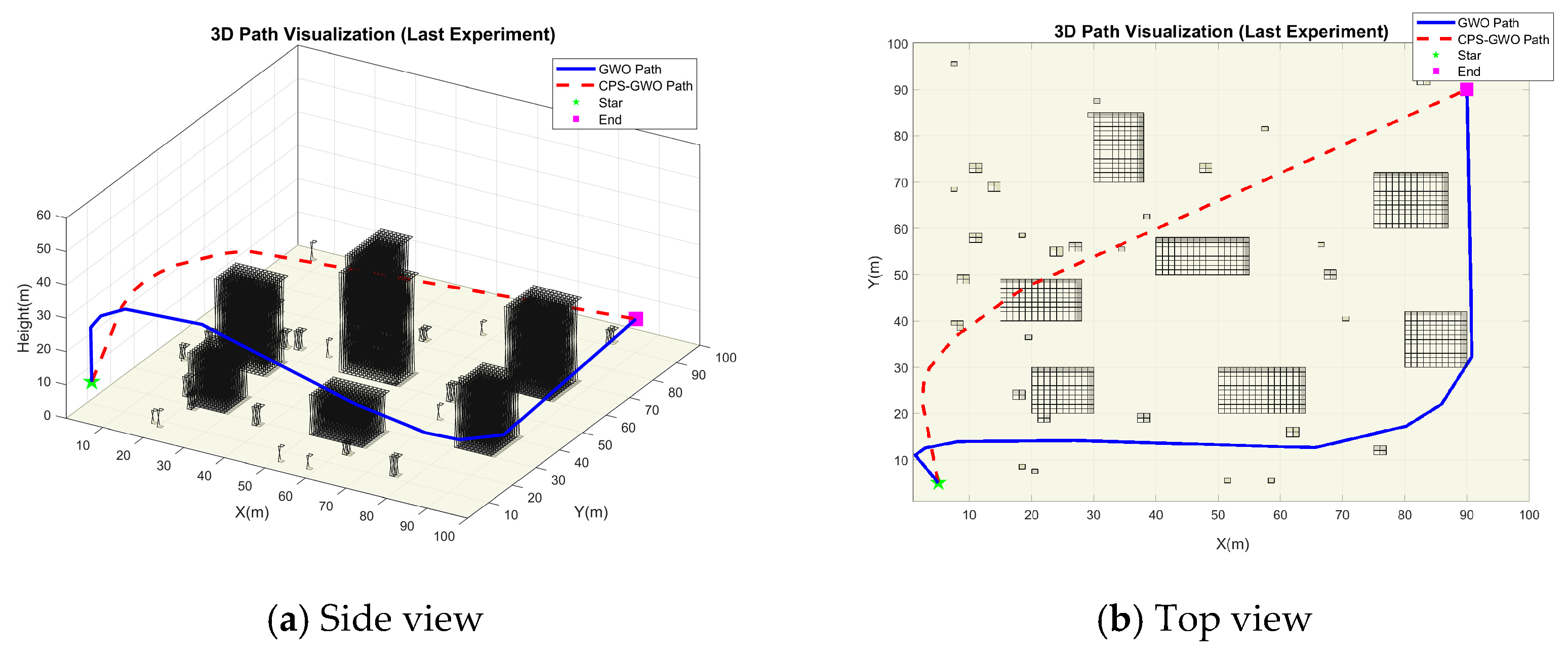

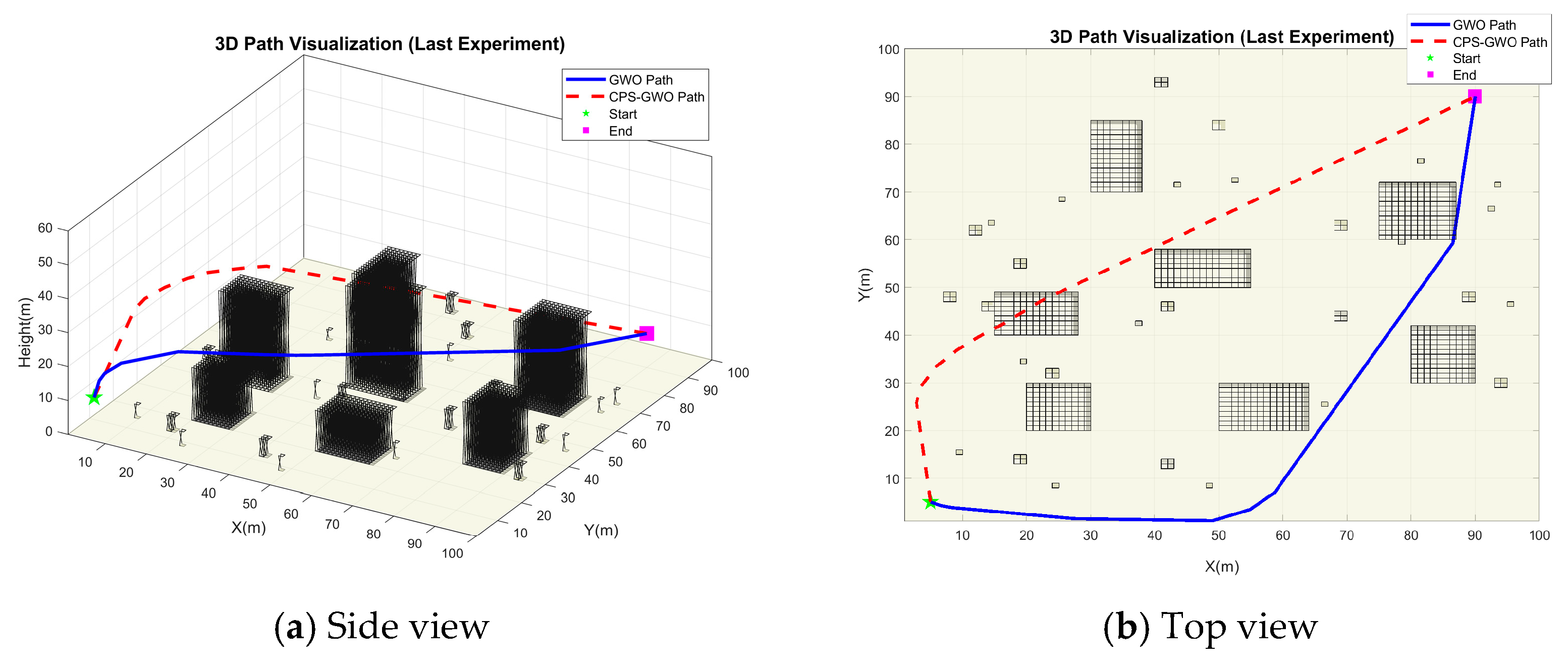

In the experiment, a population size of 40, 100, and 200 was designated as the small-scale, medium-scale, and large-scale population experiment, respectively. Following 500 iterations, the path planning results are presented in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6:

It can be seen from the above three groups of simulation experiments that the CPS-GWO exhibits good smoothness and continuity and effectively avoids all obstacles in the environment. Although the population size increases from 40 to 200, the morphology and quality of the planned paths do not change significantly; this proves that the improved algorithm proposed in this study has excellent robustness and stability under different population sizes and can efficiently and reliably address the 3D path planning problem in complex environments.

4.3. Result Analysis

To further analyze the algorithm, the convergence comparison of the three groups of experiments is shown in

Figure 7.

It can be seen from the figure that the CPS-GWO has good initial solutions and can converge quickly. The experimental data results are shown in

Table 4:

In terms of average fitness value, the CPS-GWO demonstrates superior global search performance under the same population size. It can be seen from the data in the table that in the small-scale experiment, the average optimal fitness value of the CPS-GWO is 159.78, representing a 38.53% reduction compared with the standard GWO; in the medium-scale experiment, the average optimal fitness value of the CPS-GWO further decreases to 150.45, a further 31.30% reduction compared with the latter. This result indicates that by introducing the Kent chaotic map in the population initialization stage and superimposing the chaotic disturbance mechanism during the iteration process, the CPS-GWO effectively improves the spatial distribution uniformity of the population, reduces the search blind spots caused by random initialization, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s ability to jump out of local optimality and significantly improving the overall convergence accuracy.

In terms of flight distance, the path length generated by the CPS-GWO is significantly shorter than that of the GWO under different population sizes. In the small-scale experiment, the flight path length of the CPS-GWO is 22.12% shorter than that of the GWO; even in the large-scale experiment, it is still 15.62% shorter than that of the GWO. The CPS-GWO shows a continuous downward trend in [relevant indicator, e.g., path length] as the population size increases, demonstrating high stability and robustness. This indicates that the chaotic disturbance mechanism plays a key role in maintaining population diversity, thereby helping to prevent premature convergence of the population. This further confirms the feasibility and validity of the proposed improved method.

In terms of computational time, the average computation time for both algorithms increases approximately linearly with population size, consistent with the N × T × D time complexity. Under identical settings, CPS-GWO’s runtime is approximately 2.7 times that of standard GWO, attributable to the additional computations introduced by the Kent chaotic map, nonlinear convergence control, and PSO-inspired update mechanism. However, this additional computational cost is offset by a significant improvement in optimization quality: when the population size is 100 and 200, the average fitness values of CPS-GWO decrease by approximately 35.1% and 26.8%, respectively. CPS-GWO generates shorter and more stable paths at the cost of a moderate yet acceptable increase in computational time.

5. Conclusions

Aiming to solve the inherent shortcomings of the standard GWO algorithm in 3D UAV path planning, this study proposes an improved algorithm (CPS-GWO) integrating the Kent chaotic map and PSO. To address these defects, specifically, the Kent chaotic map is employed to optimize the initial population diversity; the nonlinear adaptive control parameter balances global exploration and local exploitation; the PSO mechanism is integrated to enhance the algorithm’s optimization performance; and a multi-objective comprehensive cost function is constructed to ensure path quality.

Simulation experiments show that the CPS-GWO significantly outperforms the standard GWO and other typical improved algorithms in terms of optimal fitness, path length, smoothness, and robustness. This algorithm offers an efficient and reliable approach for UAV logistics and distribution path planning in complex urban environments.

Nevertheless, the proposed algorithm has certain limitations: it is only designed for static environments and does not consider dynamic obstacles (e.g., other UAVs and unexpected obstacles); it focuses on single-UAV path planning and does not involve multi-UAV cooperative obstacle avoidance and task allocation; the simulation environment is a simplified urban terrain, which fails to fully account for practical engineering factors such as meteorological factors and signal attenuation. In future research, we will further explore the algorithm’s application potential in multi-UAV cooperative path planning and real-time path adjustment in dynamic environments.

Author Contributions

Visualization and conceptualization, W.-Q.F.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y.; visualization, L.-F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-J.F.; data curation, K.-J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Central University Basic Research Projects (Grant No. 24CAFUC04002) and the Sichuan Engineering Research Center for Smart Operation and Maintenance of Civil Aviation Airports (Grant No. JCZX2023ZZ07 and No. JCZX2024ZZ25). This work has also been funded by Sichuan Flight Engineering Technology Research Center Project (Grant No. GY2024-30D). This work has also been funded by the Research Capacity Enhancement Program of Civil Aviation Flight University of China (Grant No. 24CAFUCGHFY03005). This work has also been funded by Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (Grant No. 202510624005). This work has also been funded by Sichuan Provincial Engineering Research Center of Domestic Civil Aircraft Flight and Operation Support (Grant No. MJCYZY202503).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely grateful to the reviewers who have been highly professional, meticulous, and dedicated. Their insightful comments have been of great value to us. We also extend our gratitude to the Editors for their prompt feedback. Additionally, we would like to thank Fan Li for his painstaking efforts in proofreading the language of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xin, R.; Feng, W.; Xu, K. Multi-UAV Trajectory Planning Based on a Two-Layer Algorithm Under Four-Dimensional Constraints. Drones 2025, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Zhan, X.; Wandelt, S. LAERACE: Taking the policy fast-track towards low-altitude economy. J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2025, 4, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Guo, H.; Hu, X. Advances in UAV Path Planning: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions. Drones 2025, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Hu, Y.; Li, W. Review of Optimization Algorithms for UAV Routes. Mod. Def. Technol. 2024, 52, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Du, Y.; Li, Y. Research on Particle Swarm Optimization-Based UAV Path Planning Technology in Urban Airspace. Drones 2024, 8, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Sha, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, X.; Bai, G.; Liu, J. IHSSAO: An Improved Hybrid Salp Swarm Algorithm and Aquila Optimizer for UAV Path Planning in Complex Terrain. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, C.; Han, Z.; Wu, W. Hybrid Swarm Intelligence and Human-Inspired Optimization for Urban Drone Path Planning. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Kaur, A.; Singh, P. UAV swarm clustering and trajectory planning: A taxonomy, systematic review, current trends and research challenges. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 128, 110697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, M.S.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, M.; Huang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Qiao, J. Enhanced Gray Wolf Optmization Algorithm That Integrates Multiple Improvement Methds. J. Jilin Univ. (Sci. Ed.)/Jilin Daxue Xuebao (Lixue Ban) 2025, 63, 829–0834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y. Research on Trajectory Planning for a Limited Number of Logistics Drones (≤3) Based on Double-Layer Fusion GWOP. Drones 2025, 9, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, X.X.; Liu, J.S. An Improved Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm to Solve Engineering Problems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3208. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Wu, Z.; Gao, W.; Meng, K.; Shi, D.; Hu, X.; Sun, Y. Whale optimisation algorithm based on Kent mapping and adaptive parameters. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Appl. 2023, 14, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, T.; Liu, Y. A Path Planning Algorithm Based on Improved GWO for Mobile Robots. Manuf. Autom. 2025, 4, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, T.; Hu, Z.; Ye, F.; Gao, L. Dynamic multi-objective lion swarm optimization with multi-strategy fusion: An application in 6r robot trajectory planning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.00114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T. Research on Intelligent Path Planning Algorithm for UAV; Changchun University of Technology: Changchun, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Lü, J.K.; Zhou, G.F.; Zhang, L.K.; Zhang, Y. Adaptive Hybrid A* and Artificial Potential Field Based on Grey Wolf Optimization for Unmanned Mining Truck Path Planning. J. Intell. Sci. Technol. 2025, 7, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G. A Novel Leader-Follower-Based Hybrid Particle Swarm-Grey Wolf Optimizer Algorithm for the Constrained UAV Path Planning. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2025, 97, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Deng, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Q.M. UAV 3D Path Planning Based on Improved Hybrid Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm. Radio Eng. 2024, 54, 918–927. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, X. Robot path planning using a hybrid grey wolf optimization algorithm. Comput. Eng. Sci. 2020, 42, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.; Chen, J.; Ma, Y. Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm with Improved Convergence Factor and Position Update Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Intelligent Human-Machine Systems and Cybernetics (IHMSC), Hangzhou, China, 24–25 August 2019; pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Lu, D.; Xiang, H.; Xu, K. Three-Dimensional Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Trajectory Planning Based on the Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.S.; Lin, H.; Xie, S.; Dong, X.; Lin, Y.; Shiva, C.K.; Mbasso, W.F. An intelligent hybrid grey wolf-particle swarm optimizer for optimization in complex engineering design problem. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, X.; Dong, N.; Liu, S.; Chen, H. UAV path planning based on a dual-strategy ant colony optimization algorithm. Intell. Robot. 2023, 3, 666–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, W. A global dynamic evolution snow ablation optimizer for unmanned aerial vehicle path planning under space obstacle threat. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Lü, S.; Mao, L.; Xu, K.; Bao, T.; Bao, X. Path planning of UAV using levy pelican optimization algorithm in mountain environment. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 2368343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).