1. Introduction

Wind energy has emerged as one of the most promising renewable energy sources for achieving carbon neutrality and mitigating climate change, with global installed capacity exceeding 900 GW and continuing rapid expansion [

1,

2,

3]. However, the inherent intermittency, volatility, and uncertainty of wind power generation pose significant challenges to power grid stability, dispatch efficiency, and renewable energy integration [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Accurate wind power forecasting (WPF) across multiple time horizons is, therefore, critical to maintaining grid security [

8], optimizing unit commitment and dispatch decisions [

9], enabling reliable integration of wind energy into modern power systems [

10], supporting electricity market operations [

11], and facilitating the transition toward sustainable energy systems.

Recent advances in deep learning have significantly improved WPF accuracy through sophisticated temporal modeling techniques. Recurrent neural networks including LSTM [

6,

12,

13], GRU [

14], and bidirectional architectures [

15,

16,

17] have been widely adopted to capture sequential dependencies through their internal memory mechanisms. However, these recurrent architectures suffer from vanishing gradient problems, limited parallelization capabilities, and difficulties in capturing very-long-range dependencies. Convolutional neural networks [

18,

19] offer an alternative approach by extracting multi-scale local features through hierarchical representations. Transformer-based architectures have emerged as powerful alternatives due to their ability to model global temporal dependencies through self-attention mechanisms, including specialized variants such as iTransformer [

20,

21]. Despite their effectiveness in achieving state-of-the-art performance, these models typically require extensive training data, substantial computational resources, and careful hyperparameter tuning, limiting their applicability in data-scarce scenarios.

Hybrid and multi-scale forecasting frameworks have been developed to combine multiple complementary techniques for enhanced prediction accuracy and robustness. Signal decomposition methods including variational mode decomposition (VMD), complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise (CEEMDAN), empirical mode decomposition (EMD) [

22,

23], and wavelet transforms [

24] decompose complex wind power series into components with distinct frequency characteristics, enabling the separate modeling of different temporal scales. Spatiotemporal modeling approaches have gained increasing attention for multi-site forecasting scenarios, leveraging graph neural networks [

25] and spatiotemporal CNNs [

26] to capture both geographical correlations and temporal evolution patterns. Advanced optimization techniques including transfer learning [

27], probabilistic forecasting [

28], and ensemble methods have further enhanced performance through improved generalization and uncertainty quantification.

Despite these advances, existing deep learning methods face three fundamental limitations. First, they primarily rely on numerical time-series data such as wind speed, direction, temperature, and historical power output, failing to leverage rich semantic information about weather patterns and domain knowledge that could significantly enhance forecasting interpretability and enable better reasoning about causal relationships. Second, most models struggle with limited training data availability, particularly critical in newly deployed wind farms without sufficient historical operational data and rare weather events that occur infrequently in training sets, substantially limiting their generalization ability. Third, conventional deep learning architectures often require extensive fine-tuning with large-scale datasets to achieve satisfactory performance, involving computationally expensive hyperparameter optimization and prolonged training procedures that increase both computational costs and deployment complexity.

Large language models (LLMs) have recently demonstrated remarkable capabilities across diverse domains, including natural language understanding, code generation, mathematical reasoning, and scientific discovery [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], offering potential solutions to the aforementioned challenges. LLMs possess several inherent advantages: robust semantic representations learned from large-scale pre-training that encode rich world knowledge, strong few-shot and zero-shot learning capabilities [

34] enabling rapid adaptation to new tasks with minimal training examples, and the ability to process and integrate multimodal information. Recent pioneering work has begun exploring LLMs for time-series forecasting [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], leveraging various adaptation techniques, including carefully designed prompt engineering, cross-modality alignment mechanisms, and reprogramming layers that transform numerical sequences into token representations. However, most existing LLM-based approaches require fine-tuning all or a substantial portion of the LLM parameters on domain-specific forecasting tasks, significantly increasing computational costs and potentially compromising the model’s generalization ability through a catastrophic forgetting of pre-trained knowledge.

To address these gaps and unlock the potential of language models for wind power forecasting while maintaining computational efficiency, we propose LLM-WPFNet (Large Language Model-empowered Wind Power Forecasting Network), a novel dual-modality framework that synergistically combines specialized time-series analysis with frozen pre-trained language models through an innovative asymmetric attention-based fusion mechanism. Our key insight is that wind power temporal patterns, including statistical properties such as mean, variance, and extreme values, as well as dynamic characteristics such as trends, periodicities, and change rates, can be effectively encoded as structured textual prompts, enabling the LLM to provide rich semantic guidance and inject domain knowledge into the forecasting process without requiring any fine-tuning of the pre-trained language model parameters. By keeping the LLM completely frozen and training only lightweight adaptation layers, LLM-WPFNet maintains the robust semantic representations learned during large-scale pre-training while dramatically reducing computational requirements.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

We propose LLM-WPFNet, a novel dual-modality fusion framework that integrates a time-series encoding branch (processing meteorological and operational data through MLP blocks, positional encoding, Transformer encoder, and 1D convolutional layers) with a frozen LLM-empowered encoding branch (extracting semantic representations from structured textual prompts), enabling effective knowledge transfer from pre-trained language models while maintaining computational efficiency by keeping the LLM parameters frozen during training.

We design a dual-modality collaborative learning mechanism where the time-series encoding branch captures temporal dynamics and meteorological patterns from numerical data, while the frozen LLM branch extracts semantic representations from structured textual prompts that describe statistical properties and temporal trends, with the attention fusion layer enabling the model to leverage both numerical patterns and semantic domain knowledge from the pre-trained language model to enhance forecasting accuracy without fine-tuning.

We conduct comprehensive experiments on four real-world wind farm datasets with capacities ranging from 36 MW to 200 MW across multiple prediction horizons (1–24 h ahead), demonstrating that LLM-WPFNet consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines including Transformer-based models Informer, PatchTST, and iTransformer) and recurrent architectures (Bi-LSTM and DLinear) by approximately 11% in both the MAE and RMSE metrics, validating the effectiveness of integrating frozen language models for wind power forecasting.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on deep learning methods for wind power forecasting and recent applications of large language models in time-series analysis.

Section 3 presents the detailed methodology of LLM-WPFNet, including the dual-modality encoding architecture, multi-head attention fusion mechanism, and training strategy.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup, datasets, and evaluation metrics and presents comprehensive results, including main performance comparisons, ablation studies, prompt design analysis, hyperparameter sensitivity analysis, and attention visualization analysis.

Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of key findings and discusses future research directions.

3. Methodology

This section presents the technical details of LLM-WPFNet (Large Language Model-empowered Wind Power Forecasting Network), the proposed dual-modality framework for wind power forecasting. We first provide an overview of the overall architecture, followed by detailed descriptions of each key module.

3.1. Framework Overview

LLM-WPFNet comprises three key modules: dual-modality encoding, multi-head attention fusion, and time-series forecasting, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Dual-modality encoding includes a time-series encoding branch and an LLM-empowered encoding branch, designed to effectively learn embeddings for input time-series data and textual prompts, respectively.

The time-series encoding branch consists of an MLP block, position encoding, a Transformer encoder, and a 1D convolutional block. The MLP block with batch normalization and dropout first transforms raw time series into intermediate representations. Position encoding is then added to incorporate temporal order information. The Transformer encoder with 8-head self-attention captures long-range temporal dependencies. Finally, a 1D convolutional block with masked multi-head self-attention extracts local temporal patterns and generates the embedded time-series tokens.

The LLM-empowered encoding branch comprises a frozen pre-trained LLM and a prompt encoder. The tokenizer converts textual prompts into token sequences, which are processed by the frozen LLM to extract semantically rich embeddings. The prompt encoder then refines these embeddings across multiple variables to generate the embedded prompt tokens.

Multi-head attention fusion employs a multi-head attention mechanism to fuse information from both modalities. The embedded prompt tokens serve as keys (K), while the embedded time-series tokens serve as both queries (Q) and values (V), enabling effective knowledge transfer from the pre-trained language model to enhance time-series representations.

Time-series forecasting applies a linear transformation to the fused embeddings, followed by an output projection layer to generate the final wind power predictions.

3.2. Dual-Modality Encoding

3.2.1. Time-Series Encoding Branch

The time-series encoding branch processes raw wind power time series through multiple stages to extract informative embeddings.

MLP Block. Given the input time-series data

, where

T denotes the number of time steps and

N represents the number of variables including meteorological features (wind speed at multiple heights, wind direction, temperature, pressure, and humidity) and historical power output across wind farm sites, the MLP block first transforms the input through two fully connected layers with regularization:

where

and

denote fully connected layers,

represents batch normalization, and

applies dropout regularization to prevent overfitting. The output

, where

D is the hidden dimension, serves as the initial embedding.

Position Encoding. To preserve temporal order information, we add sinusoidal position encodings to the MLP output:

where

denotes the position encoding matrix, with each element being computed as

where

t is the time step position and

i is the dimension index.

Transformer Encoder. The position-encoded embeddings

are fed into a Transformer encoder with an 8-head self-attention mechanism. Each encoder layer applies layer normalization, multi-head self-attention, and feed-forward networks:

where

l denotes the layer index,

represents 8-head self-attention with queries, keys, and values are all derived from the input

where

,

,

, and

are learnable projection matrices for the

h-th attention head.

One-Dimensional Convolutional Block. The output from the Transformer encoder is processed through a 1D convolutional block to extract local temporal patterns:

where

applies 1D convolution with kernel size 3 and 64 output channels, followed by batch normalization, average pooling, and dropout. Subsequently, the convolutional features undergo layer normalization and masked multi-head self-attention (MMSA):

where

represents the final embedded time-series tokens. Masked attention prevents information leakage from future time steps during training.

3.2.2. LLM-Empowered Encoding Branch

Pre-trained large language models have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in learning robust representations from large-scale text data [

41]. Inspired by recent work on aligning time series with language models [

35,

39], we leverage a frozen LLM to extract semantic embeddings from textual prompts that describe the wind power time-series characteristics. Unlike approaches that fine-tune LLMs [

36,

38], we keep the LLM parameters frozen to preserve pre-trained knowledge and reduce computational costs [

35].

LLM Selection. We select GPT-2 (117 M parameters) as the frozen backbone due to its favorable balance between semantic representation capability and practical deployment requirements. GPT-2 offers open-source accessibility ensuring reproducibility and reasonable computational efficiency for real-time forecasting operations. The compact model size facilitates edge deployment in resource-constrained wind farm environments, while the frozen architecture allows for straightforward substitution with alternative LLMs when application-specific requirements justify additional computational overhead.

Tokenization and LLM Processing. Following recent work on prompt-based time-series forecasting [

36,

37,

40], we design structured textual prompts

that encode domain knowledge about temporal patterns, magnitude scales, rate of change, and statistical properties. The domain knowledge includes (1) temporal trend patterns (e.g., “increasing trend indicates rising generation”), (2) magnitude scales providing operational context (e.g., “values ranging 45–78 MW suggests moderate output regime”), (3) rate of change enabling ramp event recognition (e.g., “every 15 min resolution captures sub-hourly dynamics”), and (4) statistical properties signaling condition uncertainty (e.g., “high variance indicates turbulent conditions”). A concrete example prompt for wind power forecasting is given as follows: “From t

1 to t

96, wind power values were 45.2, 48.7, 52.1, 55.8, 61.4, 67.9, 72.5, 78.3 MW every 15 min. The total trend value was +33.1 MW.” This structured encoding enables the LLM to recognize linguistic patterns associated with a “sustained increasing trend” that guide prediction of continued growth or potential saturation. The tokenizer converts each prompt into a sequence of token IDs:

where

represents the token sequence for the

n-th variable and

denotes the sequence length.

The token sequences are fed into a frozen pre-trained LLM (GPT-2) to generate contextualized embeddings. All parameters in the LLM remain frozen during training to preserve the pre-trained linguistic knowledge. The LLM processes the tokens through multiple Transformer layers, where each layer applies causal self-attention and feed-forward transformations. Due to the frozen nature of the LLM (indicated by the snowflake symbol in the architecture), the embeddings remain consistent across training epochs, which significantly reduces computational costs.

Token Selection. Following LLM processing, we obtain a sequence of token embeddings for each prompt. These token embeddings are organized as , where each represents the embedding of the i-th token and is the LLM’s hidden dimension. The architecture extracts multiple token embeddings from each prompt to capture comprehensive semantic information.

Prompt Encoder. To refine the LLM embeddings and align them with the time-series modality, we employ a prompt encoder that processes the token embeddings across all variables:

where

represents the embedded prompt tokens. The prompt encoder applies attention mechanisms to capture relationships between different variables’ semantic descriptions, generating refined embeddings that serve as keys (K) in the subsequent fusion module.

3.3. Multi-Head Attention Fusion

The multi-head attention fusion module integrates information from both time-series and prompt modalities through a cross-attention mechanism [

39]. Different from some cross-modality alignment approaches that treat both modalities symmetrically [

37], our design explicitly assigns different roles to each modality based on their characteristics, where the frozen LLM embeddings serve as semantic guidance for the time-series branch.

We employ an asymmetric attention mechanism wherein embedded time-series tokens function as both queries (Q) and values (V), while embedded prompt tokens serve as keys (K). This Q = TS, K = Prompt, V = TS configuration orchestrates a unidirectional information flow that fundamentally reshapes cross-modal interaction: temporal patterns actively query the frozen LLM’s semantic knowledge repository, selectively extracting relevant linguistic priors without compromising the numerical characteristics inherent to forecasting tasks. By designating time-series representations as query initiators, the model ensures that temporal dynamics govern the knowledge transfer process rather than being subordinated to linguistic representations. Concurrently, positioning LLM embeddings as passive responders (keys) circumvents the architectural misalignment that would arise if frozen text-oriented parameters were compelled to directly adapt to numerical prediction objectives. Crucially, retaining time-series tokens as values ensures that the fused output preserves essential temporal structures and numerical scales, where attention weights function as a learned semantic gating mechanism that modulates—rather than replaces—the original time-series representations.

This asymmetric design exhibits dual advantages in maintaining architectural integrity. First, it operationalizes the frozen LLM paradigm by confining all cross-modal adaptation to trainable projection matrices (, , ) while preserving pre-trained parameters intact, thereby preventing the catastrophic forgetting of linguistic knowledge. Second, alternative configurations prove architecturally incompatible: a reversed assignment (Q = Prompt, K = TS, V = TS) would necessitate frozen LLM embeddings initiating queries toward temporal data, contradicting their pre-training objective; conversely, a symmetric configuration (Q = TS, K = Prompt, V = Prompt) would allow LLM representations to dominate the output, introducing text-derived statistical properties detrimental to numerical forecasting accuracy. Our asymmetric formulation thus represents the optimal reconciliation between leveraging pre-trained linguistic knowledge and maintaining the numerical fidelity requisite for time-series prediction.

This configuration allows the model to attend to relevant semantic information from the prompts while preserving the temporal dynamics encoded in the time series:

where

,

, and

are learnable projection matrices.

The multi-head attention mechanism computes attention scores between time-series and prompt embeddings:

where

represents the attention weight matrix and

is the dimension of the key vectors. The fused embeddings

incorporate semantic knowledge from the LLM while maintaining the temporal structure of the original time series.

3.4. Time-Series Forecasting

The time-series forecasting module transforms the fused embeddings into wind power predictions through a linear layer followed by an output projection.

Linear Transformation. The fused embeddings are first processed through a linear layer to map them to an intermediate representation:

where

and

are learnable parameters.

Output Projection. The final prediction is generated through an output projection layer that maps the intermediate representation to the target space:

where

represents the predicted wind power values for

M future time steps across

N wind farm sites, and

and

are learnable parameters.

3.5. Training Strategy and Objective Function

LLM-WPFNet is trained in an end-to-end manner using a combination of prediction loss and regularization. Following best practices in time-series modeling [

43,

44], we employ batch normalization and layer normalization to stabilize training and improve convergence. The snowflake symbol in the architecture indicates that the LLM remains frozen during training, while the flame symbol marks components with trainable parameters, including the MLP block, the Transformer encoder, the 1D convolutional block, the prompt encoder, the attention fusion module, and the forecasting layers.

The training objective consists of two components:

where

is a hyperparameter that balances prediction accuracy and model complexity.

The prediction loss employs Mean Squared Error (MSE):

where

represents the ground-truth wind power value at time step

m for wind farm site

n and

is the corresponding prediction.

The regularization term

applies

regularization to trainable parameters:

where

represents the set of trainable parameters (excluding the frozen LLM parameters).

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Datasets

We conduct experiments on wind farm datasets collected from multiple sites with different nominal capacities. The datasets contain measurements recorded every 15 min throughout 2019, with comprehensive meteorological and operational variables. Details are summarized as follows:

Wind Farm Site 1 (nominal capacity: 99 MW);

Wind Farm Site 2 (nominal capacity: 200 MW);

Wind Farm Site 3 (nominal capacity: 66 MW);

Wind Farm Site 4 (nominal capacity: 36 MW).

Each dataset includes 12 variables: wind speed measurements at multiple heights (10 m, 30 m, 50 m, and hub height), wind direction measurements at multiple heights, meteorological variables (air temperature, atmospheric pressure, and relative humidity), and the target variable power output (MW). The data were collected through SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems at 15 min intervals throughout 2019–2020 and were provided by the Chinese State Grid with proper authorization [

45]. The datasets are split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test sets (15%) following a temporal split to ensure realistic evaluation of forecasting performance.

Following the systematic preprocessing protocol for renewable energy data [

45], we implement a comprehensive data quality control pipeline to ensure reliable model training and evaluation. The datasets contain 15 min resolution measurements throughout 2019–2020, collected via SCADA systems at each wind farm site. Missing data characteristics vary across sites, with typical missing rates being below 2% for meteorological variables and below 1% for power output. For handling missing value, we identify entries marked as 0, null, “NA”, “0.001”, “−99”, or “–” as missing data. Short-term gaps (up to 10 consecutive time steps, corresponding to 2.5 h) are filled using forward/backward filling or linear interpolation to maintain temporal continuity, while long-term gaps exceeding 100 consecutive time steps (over 25 h) are removed from the dataset, as they likely indicate equipment maintenance periods. For outlier detection, we employ the interquartile range (IQR) method with a threshold of 1.5 × IQR to identify values significantly deviating from the normal range. However, considering the inherent volatility of wind power generation where rapid ramp events and weather fronts cause legitimate extreme values, we retain most detected outliers that fall within physical constraints (wind speed below 50 m/s and power output within turbine capacity), allowing the model to learn from the full spectrum of operational scenarios. This preprocessing ensures data integrity while preserving the natural variability essential to robust wind power forecasting.

4.2. Experimental Setting

The lookback window length is fixed at 96 time steps (24 h), and we evaluate predictions at multiple horizons, {4, 12, 24, 48, 96} time steps, corresponding to {1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h} ahead forecasting. These forecast horizons are crucial to wind power grid integration and operational planning.

We use GPT-2 (117 M parameters) as the frozen backbone language model. The trainable components include the MLP block, the Transformer encoder, the 1D convolutional block, the prompt encoder, the attention fusion module, and forecasting layers. The model is trained using the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.0005 (5 ), a batch size of 32 for training, and a batch size of 1 for testing to ensure fair comparison. Each experiment is repeated three times with different random seeds (42, 123, and 2024), and we report the average performance. All experiments are conducted on NVIDIA A100 GPUs with 40 GB of memory.

Table 1 summarizes the key hyperparameters used in our experiments. These settings are carefully tuned to ensure fair comparison across all models while maintaining computational efficiency.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

We employ two widely used evaluation metrics to assess forecasting performance:

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

where

and

represent the ground-truth and predicted power values at time step

m for Wind Farm Site

n,

M is the prediction horizon, and

N is the number of wind farm sites. Lower values of both metrics indicate better forecasting performance.

4.4. Baselines

We evaluate five baseline models representing state-of-the-art approaches in time-series forecasting:

(1) Recurrent neural networks: Bi-LSTM [

15] captures sequential dependencies through bidirectional long short-term memory units.

(2) Transformer-based models: Informer [

46] introduces ProbSparse attention for long-term forecasting efficiency; PatchTST [

47] processes time series as patches for enhanced representation; iTransformer [

20,

21] inverts the architecture to model multivariate correlations.

(3) Linear-based method: DLinear [

48] demonstrates that simple linear layers with decomposition achieve competitive performance. These baselines represent current best practices in deep learning for time-series forecasting, ensuring a rigorous benchmarking of our proposed approach.

4.5. Main Results

Table 2 presents the forecasting performance comparison across different prediction horizons on all four wind farm sites. We report the average MAE and RMSE values over three independent runs with different random seeds (42, 123, and 2024). Standard deviations are shown for the average rows to demonstrate statistical significance, with typical values ranging from 2 to 5% of the mean, confirming the stability and reproducibility of the results.

LLM-WPFNet achieves state-of-the-art performance across all prediction horizons and all four wind farm sites, outperforming the second-best baseline by approximately 11% in both MAE and RMSE on average. This consistent improvement validates the effectiveness of the dual-modality fusion design in leveraging both temporal patterns from time series and semantic knowledge from the frozen language model. Notably, the performance advantage is consistent across sites with different capacities (36 MW to 200 MW), demonstrating strong generalization ability.

The results reveal three critical patterns that illuminate the mechanisms underlying our dual-modality approach. First, examining prediction horizon effects, performance improvement over Informer increases from 6.9% at h = 4 to 19.1% at h = 96 for Site 1, with particularly pronounced gains at longer horizons. This pattern suggests that as prediction distance increases, historical patterns may provide diminishing guidance for extrapolation, whereas semantic knowledge from the LLM could act as supplementary guidance. The frozen language model, having encountered diverse descriptions of temporal phenomena during pre-training, potentially provides contextual understanding that complements pattern-based extrapolation. Second, cross-site analysis reveals that larger wind farms (Site 2: 200 MW) exhibit greater absolute errors but similar relative improvements (13.1%) compared with smaller sites (Site 4: 36 MW, 14.3%), suggesting that the dual-modality framework’s advantage stems from the improved modeling of temporal dynamics rather than capacity-dependent calibration. The consistency across diverse operational scales validates that semantic representations capture general forecasting principles applicable regardless of physical system size. Third, the performance gap between LLM-WPFNet and the baselines widens more dramatically for iTransformer (39.1%) and Bi-LSTM (29.3%) compared with Informer (12.5%), indicating that semantic guidance particularly benefits architectures that struggle with long-term dependency modeling, serving as an architectural bottleneck compensator.

Among the baselines, Transformer-based models significantly outperform RNN and linear methods. iTransformer and PatchTST achieve competitive performance due to their ability to capture multivariate correlations and long-range temporal dependencies. Bi-LSTM shows reasonable performance in short-term forecasting but degrades rapidly for longer horizons, exposing the fundamental limitation of recurrent architectures in maintaining gradient flow across extended sequences. DLinear, despite its simplicity, provides a strong baseline, confirming recent findings that properly configured linear models can be surprisingly effective for time-series forecasting when temporal patterns exhibit sufficient regularity. The substantial performance gap between DLinear and other methods (85.7% average degradation) suggests that wind power forecasting involves complex non-linear dynamics that simple decomposition and linear projection cannot adequately model.

Despite incorporating a frozen 117 M parameter GPT-2 model, LLM-WPFNet maintains computational efficiency by training only the lightweight dual-modality encoding and fusion modules, significantly reducing the trainable-parameter count and memory requirements compared with fine-tuning the entire language model. This architectural decision reflects a broader insight about transfer learning in time series: rather than adapting the entire semantic representation space to numerical forecasting (which risks catastrophic forgetting and requires massive data), our approach strategically queries the frozen knowledge base through learned attention mechanisms, analogous to how retrieval-augmented generation systems access external knowledge without re-training foundation models. The frozen architecture enforces a valuable inductive bias—semantic embeddings must remain interpretable through their original linguistic lens, preventing the model from collapsing semantic distinctions into arbitrary numerical encodings and ensuring that knowledge transfer retains meaningful structure.

Table 3 provides a systematic summary of relative improvements achieved by LLM-WPFNet over all baseline models across the four wind farm sites. The results demonstrate consistent superiority across diverse wind farm characteristics, with improvements ranging from 11.2% to 13.8% over state-of-the-art Transformer-based methods (Informer, PatchTST, and iTransformer), 31.4% to 45.7% over recurrent architectures (Bi-LSTM), and 83.5% to 84.8% over simple linear methods (DLinear) on average. These stratified improvements reveal a hierarchical pattern: the performance gain inversely correlates with baseline sophistication, with the largest margins being observed against purely linear models and progressively smaller (yet substantial) advantages over increasingly complex architectures. This gradient reflects diminishing marginal returns from architectural complexity alone—modern Transformer baselines already capture sophisticated temporal patterns, yet still benefit significantly from semantic augmentation. The consistent 11–15% improvement over Informer, a mature architecture specifically designed for long-range forecasting, is particularly noteworthy: it suggests that semantic knowledge provides genuinely orthogonal information rather than merely compensating for architectural deficiencies. The relative consistency of improvements across different wind farm sites indicates that the dual-modality advantage arises from fundamental forecasting principles rather than dataset-specific artifacts, supporting generalizability to unseen wind farm deployment.

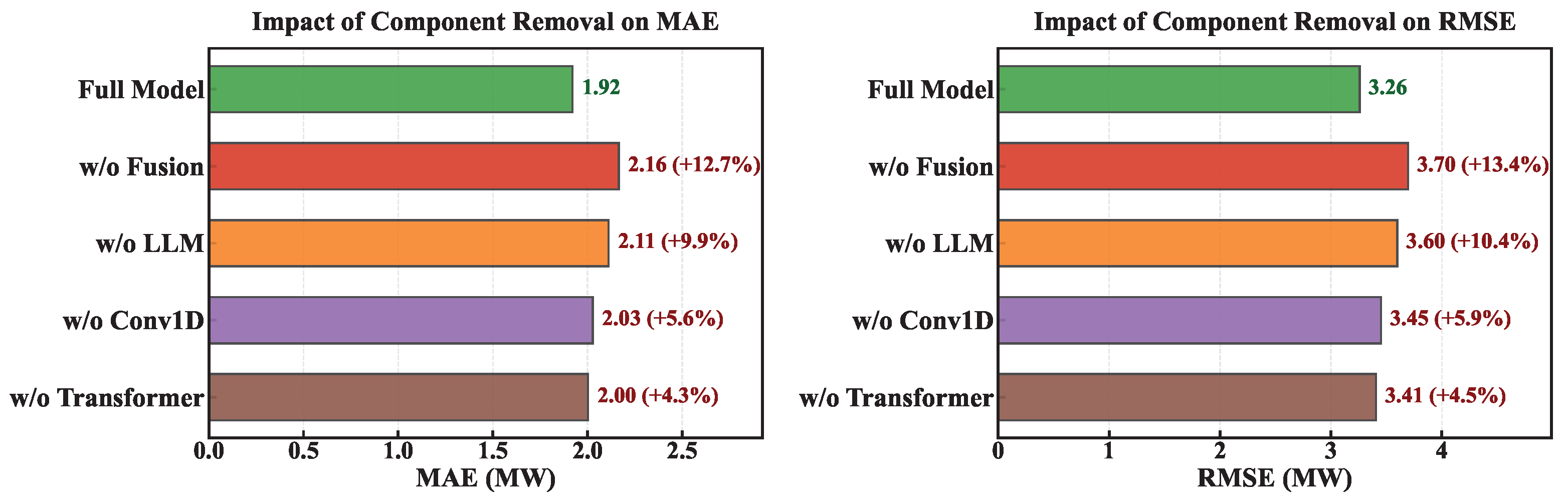

4.6. Ablation Study

To systematically validate the contribution of each component, we conduct ablation studies on Wind Farm Site 1 by removing individual modules while keeping other components unchanged. The results are presented in

Figure 2, showing average MAE and RMSE across all prediction horizons. We evaluate four variants: w/o Fusion (replacing multi-head attention fusion with simple concatenation), w/o LLM (removing the LLM-empowered encoding branch), w/o Conv1D (removing the 1D convolutional block), and w/o Transformer (removing the Transformer encoder).

Multi-head attention fusion has the most significant impact, with performance degrading by approximately 12.7% in MAE when replaced with simple concatenation. This validates our design choice of the asymmetric query–key–value assignment strategy (TS as Q&V, Prompt as K), which enables selective knowledge transfer from prompt embeddings based on time-series queries. The mechanism underlying this substantial contribution operates at two levels. At the architectural level, attention-based fusion implements dynamic, context-dependent modality integration: different temporal patterns query different semantic concepts, with attention weights effectively routing information flow based on instantaneous relevance. The model can adaptively emphasize different prompt tokens encoding various temporal characteristics (such as change rate, trend magnitude, mean level, and variance) depending on the temporal context. Simple concatenation, by contrast, enforces static fixed-weight integration that cannot adapt to varying temporal contexts, explaining the dramatic 12.7% degradation. At the information-theoretic level, attention fusion performs soft feature selection in the joint semantic–temporal representation space, dynamically allocating representational capacity to the most informative modality dimensions while suppressing noise. This selective integration prevents semantic knowledge from contaminating temporal representations when unhelpful, while amplifying its contribution when extrapolation confidence is low.

The LLM-empowered branch is the second most critical component—removing it causes 9.9% performance degradation, confirming that semantic embeddings from the frozen language model provide valuable complementary information beyond temporal patterns. This finding addresses a fundamental question in cross-modal learning: can knowledge learned from one domain (natural language) genuinely transfer to another (numerical time-series forecasting)? The 9.9% performance drop, substantial yet smaller than fusion’s contribution, reveals a nuanced answer. Semantic knowledge does not directly encode wind power dynamics; rather, it may provide abstract relational priors about temporal phenomena—concepts of monotonicity, periodicity, stability, and transition—that potentially generalize across domains. The frozen LLM, though never explicitly trained on time series, learned from text corpora where humans frequently describe temporal patterns using consistent linguistic structures. When prompted with descriptions like “increasing trend” or “high variance,” the LLM activates embedding subspaces shaped by similar textual descriptions, potentially serving as a form of prior knowledge over temporal behaviors. The gap between fusion’s importance (12.7%) and LLM branch importance (9.9%) suggests that how modalities are integrated matters nearly as much as what information they provide—a critical insight for future multi-modal architectures.

The 1D convolutional block contributes to capturing local temporal patterns, with its removal leading to 5.6% degradation. This component contributes to capturing local temporal patterns. Wind power generation exhibits high-frequency fluctuations (sub-hourly) that may display strong local autocorrelation but weak long-range structure. Convolutional filters with receptive fields spanning three–five time steps effectively capture these localized perturbations, extracting features such as acceleration magnitude and local volatility that inform short-term predictability. The Transformer encoder, optimized for global context through self-attention, cannot efficiently model such localized patterns without consuming disproportionate parameters. This complementarity—Conv1D for local structure, Transformer for global context—reflects an important principle: multi-scale temporal phenomena require multi-scale architectural components. The moderate but non-negligible contribution (5.6%) validates that effective forecasting demands hierarchical temporal modeling.

The Transformer encoder shows moderate but consistent contribution, with its removal causing approximately 4.3% degradation. While smaller than other components’ contributions, this result requires careful interpretation. The Transformer’s relatively modest impact does not indicate limited value; rather, it reflects redundancy between long-range modeling mechanisms. The LLM branch, through the semantic encoding of historical trends spanning the full lookback window, implicitly captures long-range dependencies that partially substitute for Transformer-based temporal modeling. This redundancy is deliberate: robust forecasting benefits from multiple pathways for critical information, providing graceful degradation when individual components underperform. The ablation hierarchy (Fusion > LLM > Conv1D > Transformer) reveals the system’s architectural priorities: cross-modal integration dominates, complemented by semantic priors and local pattern extraction, with long-range temporal modeling serving as a supporting mechanism. This ordering provides practical guidance for resource-constrained deployment—if computational budgets require simplification, the Transformer encoder could be compressed with minimal performance loss, whereas fusion and LLM components are non-negotiable.

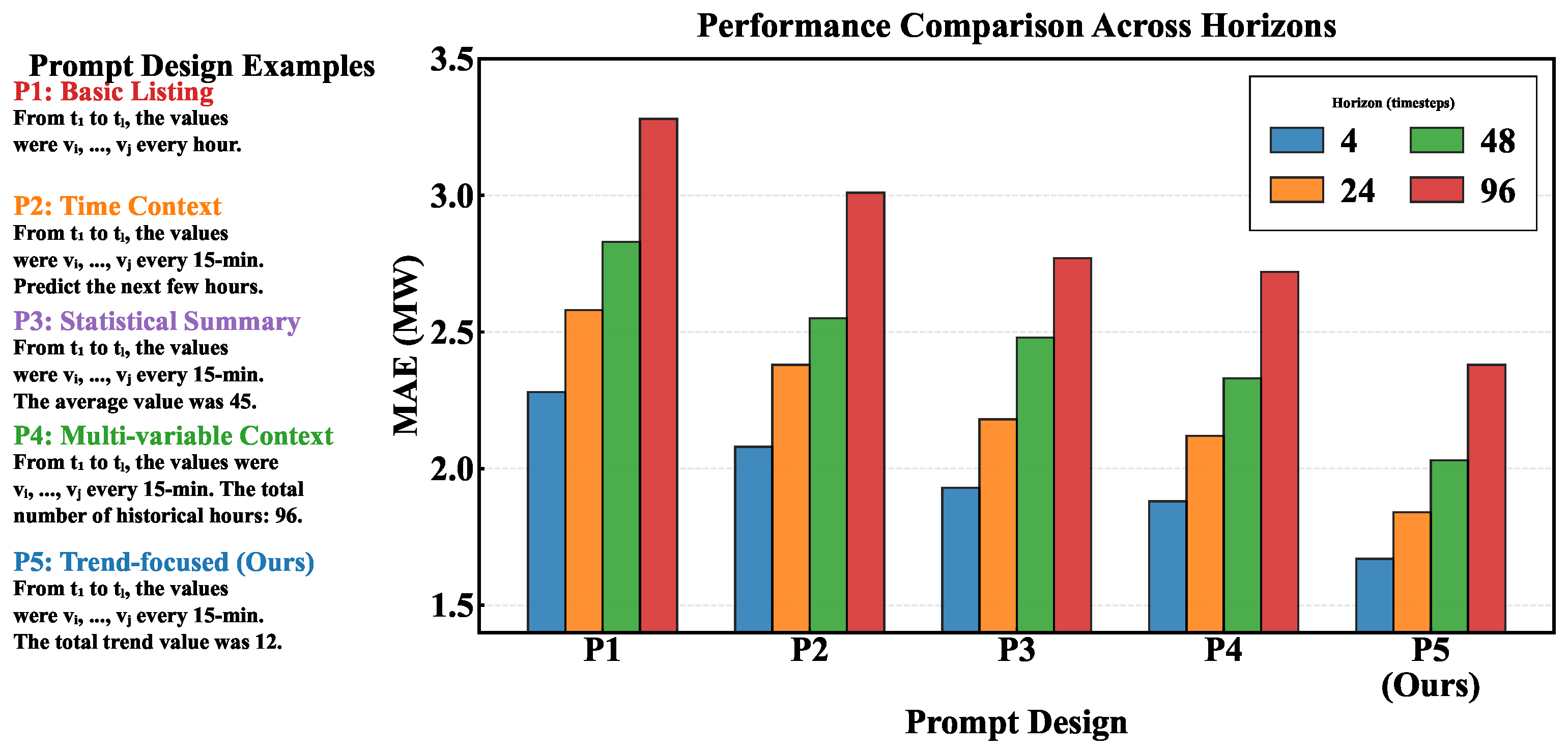

4.7. Prompt Design Analysis

Prompt design is critical to LLM-based time-series forecasting, as it determines how temporal information is encoded for the language model. We systematically evaluate five prompt templates with different focuses: basic value listing (Prompt 1), time-stamped context (Prompt 2), statistical summary (Prompt 3), multi-variable context incorporating meteorological features (Prompt 4), and our trend-focused design that combines historical values with explicit trend quantification (Prompt 5). The prompts are designed with increasing complexity to identify the most effective information encoding strategy for wind power forecasting.

As shown in

Figure 3, the trend-focused prompt (Prompt 5) achieves the best performance across all prediction horizons, outperforming the simplest prompt (Prompt 1) by approximately 10% in MAE when averaged across all horizons, with the improvement becoming more pronounced for longer prediction horizons (reaching approximately 27% at 96 time steps). This substantial gap illuminates a fundamental principle in LLM-based time-series forecasting: effective prompts must bridge the semantic gap between numerical sequences and linguistic concepts that the LLM’s pre-training optimized for. The explicit encoding of trend information (

) translates raw temporal dynamics into a linguistically grounded summary statistic—“The total trend value was +33.1 MW”—that resonates with the LLM’s training on textual descriptions of change and progression. This design exploits a cognitive alignment: humans naturally describe time series through directional trends and magnitude shifts rather than exhaustive value enumerations, and text corpora reflect this preference. By conforming prompts to this human-centric encoding, we enable the LLM to leverage semantic associations learned from millions of temporal descriptions in natural language, effectively accessing a vast meta-dataset of how temporal phenomena are conceptualized and communicated.

Multi-variable context (Prompt 4) ranks second-best, demonstrating that incorporating meteorological variables helps the LLM understand physical relationships governing wind power generation, though it underperforms Prompt 5 by approximately 3% in MAE when averaged across all horizons, with the gap widening to approximately 12.5% at longer horizons (96 time steps). This relative ranking reveals a hierarchy of prompt informativeness: causal drivers (wind speed and atmospheric pressure) provide context, but without directional summaries (trends), the LLM struggles to synthesize disparate variables into coherent extrapolation guidance. The performance gap suggests that while multi-variable prompts expand semantic context, they dilute focus on the temporal continuity that forecasting fundamentally requires. This finding challenges a common assumption in multi-modal learning—that more information universally improves performance—by demonstrating that information structure and relevance matter more than quantity.

Simple prompts show significantly worse performance, exposing critical failure modes in cross-modal information encoding. Basic value listing (Prompt 1) performs the poorest because it treats time series as unstructured token sequences, analogous to encoding images as raw pixel intensities without spatial structure. The LLM, lacking explicit inductive biases for numerical sequences, cannot efficiently extract meaningful patterns from such representations—its attention mechanisms optimize for semantic coherence in linguistic space, not numerical regularity detection. Temporal context (Prompt 2) shows modest improvement by anchoring values within time boundaries (“From t1 to t96”), providing minimal semantic scaffolding that helps the LLM interpret the sequence as a temporal progression. Statistical summary (Prompt 3) represents an opposite failure mode: excessive abstraction discards fine-grained dynamics, reducing the time series to scalar statistics (mean and variance) that erase the sequential structure essential to extrapolation. Ironically, this prompt provides semantically interpretable summaries but destroys predictive informativeness, highlighting that interpretability and utility do not always align. Across all prompt designs, the MAE consistently increases with the prediction horizon (from 4 to 96 time steps), reflecting the inherent challenge of long-term forecasting. However, the performance advantage of the trend-focused prompt becomes progressively more pronounced at longer horizons, suggesting that explicit trend encoding provides particularly valuable guidance when extrapolating further into the future where pattern-based methods struggle.

The substantial performance span across prompt designs (averaging approximately 10% across all horizons but reaching over 27% at longer horizons) has profound implications beyond wind power forecasting. It suggests that LLM-based time-series methods inherit a form of “prompt brittleness”—performance depends sensitively on how numerical data are verbalized, introducing a new hyperparameter space that lacks the theoretical grounding of traditional model architectures. Our trend-focused prompt strikes an optimal balance between detailed historical values (preserving temporal structure) and high-level trend abstractions (enabling semantic grounding), but this balance is domain-specific and may not generalize to other forecasting tasks with different temporal characteristics. This limitation motivates future research on prompt meta-learning or automatic prompt optimization techniques that can systematically discover effective encodings without extensive manual engineering, analogous to neural architecture search for model design.

4.8. Prompt Length Sensitivity Analysis

The prompt length determines how much temporal information is encoded for the frozen LLM to process. We systematically evaluate five prompt lengths, {4, 8, 12, 16, 24} tokens, on Wind Farm Site 1 across all prediction horizons, while maintaining the trend-focused prompt template structure to isolate the length effect.

Table 4 presents the results showing the accuracy–efficiency trade-off.

The results reveal a clear pattern validating 12 tokens as optimal. Very short prompts (four–eight tokens) provide insufficient temporal context—with only four tokens, the prompt can barely convey basic trend information, resulting in 8.9% performance degradation (MAE 2.09 MW). The eight-token configuration allows for sparse historical values but lacks comprehensive statistical properties, yielding 5.3% worse performance (MAE of 2.02 MW). In contrast, the 12-token configuration captures essential temporal characteristics, including trend quantification, representative historical values, and frequency indicators within a concise format aligned with GPT-2’s attention mechanism. Longer prompts (16–24 tokens) enable more detailed descriptions but show only marginal improvements—the 16-token variant improves by merely 1.6% while increasing inference time by 17.3%, and the 24-token configuration provides a 2.4% gain at 38.6% computational overhead—making them impractical for real-time operational forecasting.

The 12-token structure is decomposed into four functional components: (1) the temporal context boundary (2 tokens: “From ”) establishes the time window scope, (2) representative historical values (6 tokens: “values were ”) provide concrete numerical examples sampled from the lookback window, (3) the frequency indicator (2 tokens: “every 15 min”) specifies the temporal resolution, and (4) trend quantification (2 tokens: “trend ”) explicitly encodes the cumulative change direction and magnitude. This fixed structure ensures consistency across different wind farm sites and meteorological conditions while maintaining computational efficiency for operational deployment.

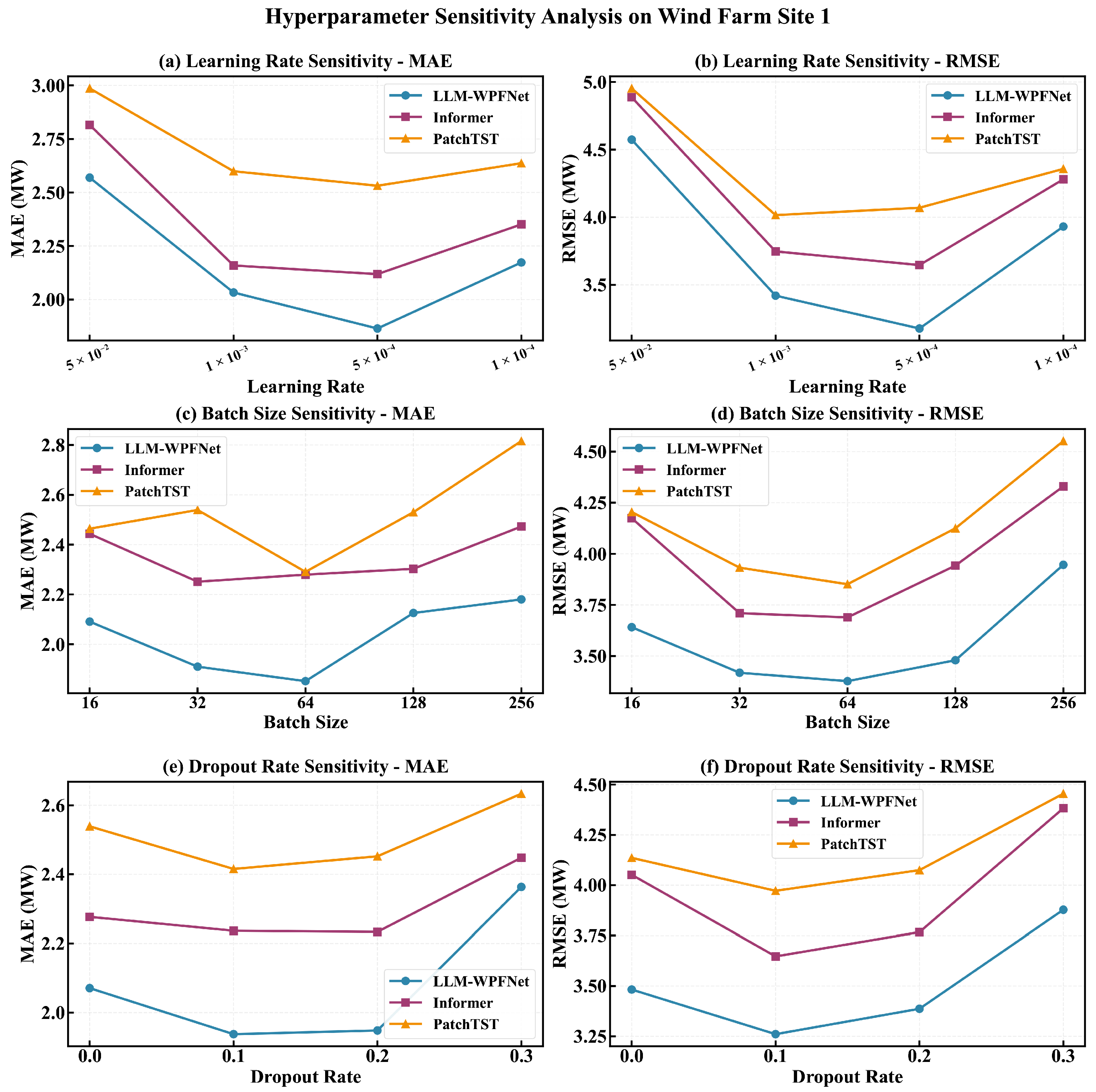

4.9. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

Understanding how hyperparameters affect model performance is crucial to practical deployment and reproducibility. We conduct comprehensive sensitivity analysis on three key hyperparameters—learning rate, batch size, and dropout rate—that significantly impact training dynamics and generalization.

Figure 4 presents the sensitivity curves for LLM-WPFNet alongside two competitive baselines (Informer and PatchTST) on Wind Farm Site 1, evaluated using both MAE and RMSE metrics across different parameter settings.

The learning rate demonstrates the most pronounced impact on all models. By evaluating four learning rates (5 , 1 , 5 , and 1 ), we observe that extremely large learning rates (5 ) cause severe training instability, with an increase of over 60% in the MAE, while very small learning rates (1 ) lead to slow convergence with 25–30% performance degradation. LLM-WPFNet achieves optimal performance at 5 , maintaining a consistent 11–15% advantage across the entire spectrum. Batch size analysis (16, 32, 64, 128, and 256) reveals that small batches (16) introduce excessive gradient noise, with 18–20% degradation, while very large batches (128–256) suffer from reduced stochastic regularization. The optimal batch size of 32 provides the best balance. Interestingly, baseline models exhibit performance crossovers at different batch sizes, while LLM-WPFNet demonstrates greater robustness, suggesting that semantic knowledge from the frozen LLM provides implicit regularization. Dropout rate evaluation (0.0, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3) shows that without dropout, all models exhibit overfitting (15–18% degradation), while excessive dropout (0.3) causes severe underfitting (30–35% loss). The optimal dropout rate of 0.1 balances regularization with model capacity. Notably, LLM-WPFNet is less sensitive to dropout variations than baseline models, with the frozen LLM embeddings acting as a stable semantic anchor that reduces reliance on dropout for regularization.

4.10. LLM Backbone Comparison

To validate our choice of GPT-2 as the frozen LLM backbone, we conduct comparative experiments with alternative language models on Wind Farm Site 1 across all prediction horizons.

Table 5 presents the performance comparison including BERT-base (110 M), GPT-2 (117 M), GPT-2 Medium (345 M), and GPT-2 Large (774M). Results show means ± std over three runs with different random seeds. Inference time is measured on an NVIDIA A100 GPU with a batch size of 1.

The results demonstrate that GPT-2 achieves substantial improvement over BERT-base (a 11.9% MAE reduction), validating the effectiveness of GPT-2’s causal language modeling pre-training for time-series semantic understanding. However, larger GPT-2 variants yield only marginal gains—GPT-2 Medium improves by merely 2.1% (1.88 vs. 1.92 MW) while doubling inference time (23.8 ms vs. 11.4 ms), and GPT-2 Large provides a 3.1% improvement (1.86 MW) at 265% computational overhead (41.6 ms). This finding confirms that the performance bottleneck lies primarily in cross-modal alignment between time-series and textual embeddings rather than in the frozen LLM’s semantic capacity, validating that moderately sized language models suffice for effective knowledge transfer in dual-modality forecasting frameworks. The diminishing returns from larger models, combined with GPT-2’s favorable inference efficiency and accessibility, justify our selection for practical wind power forecasting deployment.

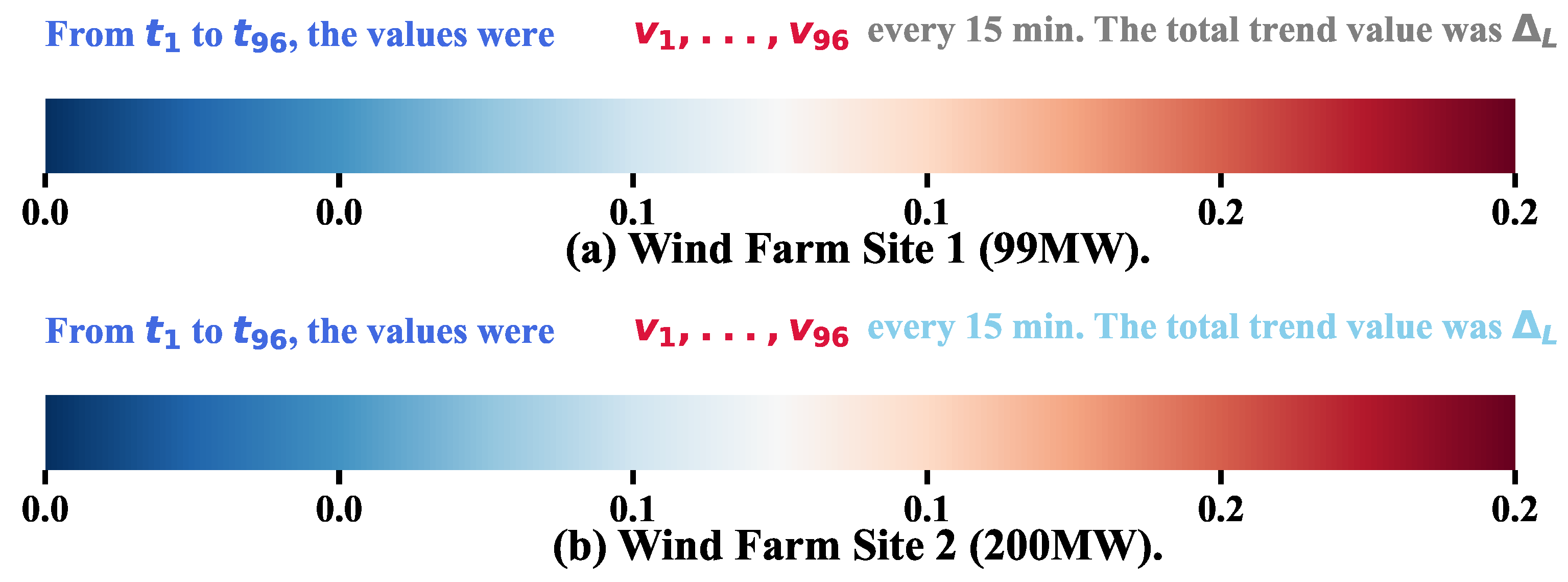

4.11. Attention Visualization Analysis

To validate that multi-head attention fusion performs meaningful semantic guidance rather than simple feature averaging, we conduct two complementary visualization analyses. First, we examine the attention weight distributions between time-series queries and prompt keys across different prediction horizons. Second, we analyze the internal attention mechanism within the frozen LLM to verify how the trend quantification token captures information from the prompt structure.

Cross-Modal Attention Analysis. To understand how the multi-head attention fusion module integrates information from both time series and LLM branches, we visualize the average attention patterns across all eight attention heads.

Figure 5 presents the attention weight distribution between TS branch embeddings (queries) and LLM branch prompt embeddings (keys) for Wind Farm Site 1.

The attention weights are computed through a scaled dot-product attention mechanism, where TS branch embeddings serve as queries (Q) and LLM branch prompt embeddings serve as keys (K). The attention scores are obtained by computing , followed by a softmax operation to normalize the scores into attention weights. The heatmap displays the average attention weights across all eight attention heads, computed by taking the mean of attention weights from each head. The attention heatmap reveals non-uniform attention distribution across features, with wind-related measurements (wind speed and direction at 10 m, 30 m, 50 m, and hub height) receiving consistently higher attention weights than environmental variables such as air temperature, atmospheric pressure, and relative humidity. The attention patterns exhibit temporal variations, with wind features showing peak attention at specific time steps (e.g., t = 38 and t = 76), while environmental features remain at lower attention levels throughout the sequence. This selective attention mechanism indicates that the fusion module learns to prioritize semantically relevant LLM prompt embeddings based on both feature characteristics and temporal context, rather than applying uniform weighting across all features. The observed patterns validate that the multi-head attention fusion implements selective knowledge transfer, where TS branch embeddings dynamically query and integrate relevant semantic information from the LLM branch.

To understand how the frozen LLM processes temporal information within prompts, we visualize the attention patterns of the last token

(trend quantification) from the final layer of GPT-2. We segment the prompt into distinct components: temporal context boundary (“From

to

”), time-series values (

), frequency indicator (“every 15 min”), and the trend token itself.

Figure 6 presents the attention distribution of the last token to previous segments for two representative wind farm sites with different capacity (99 MW and 200 MW).

The visualization reveals that the highest attention weights from the token are consistently directed toward the time-series value segment, with attention scores concentrated in the range of 0.1–0.2 across both sites. This attention pattern demonstrates that the trend quantification token effectively captures numerical information from the historical values, synthesizing them into a semantic representation of temporal dynamics. The consistency of this attention behavior across sites with different capacity (99 MW vs. 200 MW) validates that the frozen LLM’s internal mechanism reliably extracts relevant temporal information from structured prompts regardless of operational scale. This finding confirms that our prompt design successfully enables the frozen LLM to ground its semantic embeddings in actual time-series values, bridging the gap between linguistic representations and numerical forecasting tasks.

4.12. Limited Training Data Analysis

To validate the effectiveness of LLM-WPFNet in data-scarce scenarios, we conduct experiments with varying quantities of training data on Wind Farm Site 1 with 24 h ahead forecasting. We compare LLM-WPFNet against the best-performing baselines (Informer and PatchTST) using 10%, 25%, 50%, and 100% of the training data while keeping the validation and test sets unchanged. This experiment directly addresses one of the key motivations: leveraging LLMs’ semantic knowledge to compensate for limited training data availability.

As shown in

Table 6, LLM-WPFNet demonstrates superior performance across all data regimes, with the performance gap becoming more pronounced as the training data decrease. With only 10% of training data, LLM-WPFNet achieves a 17.6% lower MAE compared with the best baseline (Informer), significantly outperforming the 5.9% improvement observed with the full training data. This validates our hypothesis that semantic knowledge from the frozen LLM provides valuable domain guidance that is particularly beneficial when training data are scarce. The consistent performance degradation across all models with reduced training data confirms that data scarcity remains a fundamental challenge. However, LLM-WPFNet’s relative advantage increases from 5.9% (100% of data) to 17.7% (10% of data), demonstrating that the dual-modality design effectively leverages pre-trained linguistic knowledge to compensate for limited training samples. This finding is particularly relevant for practical deployment scenarios such as newly established wind farms or rare weather conditions where historical data are limited.

4.13. Model Efficiency Analysis

To evaluate the computational efficiency of LLM-WPFNet, we compare training parameters, GPU memory consumption, and inference speed against the baseline models on Wind Farm Site 1. All models are trained with batch size 32 on NVIDIA A100 GPUs, and inference speed is measured as milliseconds per sample averaged over 100 runs.

Table 7 presents the efficiency comparison of LLM-WPFNet against baseline models on Wind Farm Site 1. To ensure fair comparison, all models are trained with a batch size of 32 on NVIDIA A100 GPUs. The results show that LLM-WPFNet has significantly fewer trainable parameters (3.2 M) compared with Transformer-based models (9.1–14.2 M), thanks to the frozen LLM design where the 117 M parameter GPT-2 remains untrainable. GPU memory consumption (8.9 GB) is comparable to that of Informer (9.2 GB) and lower than that of TimesNet (10.5 GB), as frozen parameters do not require gradient storage during backpropagation. Inference time (11.4 ms/sample) is slightly higher than for PatchTST (6.2 ms) but faster than for Bi-LSTM (12.3 ms), remaining practical for real-time applications. This demonstrates that the frozen LLM design does not increase computational costs substantially and essentially improves prediction accuracy by 11% while training only 25% of Informer’s parameters and 35% of PatchTST’s parameters.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents LLM-WPFNet, a novel dual-modality framework that leverages frozen pre-trained language models to enhance wind power forecasting. The proposed approach addresses key challenges in time-series prediction by effectively integrating temporal dynamics from time-series data with semantic knowledge from large language models through an asymmetric multi-head attention fusion mechanism. Comprehensive experiments on four wind farm datasets with different nominal capacity (36–200 MW) across five prediction horizons (1–24 h ahead) demonstrate that LLM-WPFNet consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines by approximately 11% in both MAE and RMSE. Ablation studies validate the effectiveness of each component, with multi-head attention fusion and the LLM-empowered branch being the most critical contributors to performance. Systematic analyses of LLM backbone selection, prompt length optimization, and attention configuration design confirm the robustness of our architectural choices.

Key advantages of LLM-WPFNet include superior forecasting accuracy through effective dual-modality learning, computational efficiency by maintaining the LLM frozen during training with significantly fewer trainable parameters than baseline models, and strong few-shot learning capability with 17.6% improvement over the best baseline when trained on only 10% of data. The frozen LLM design maintains competitive computational costs while benefiting from robust semantic representations learned from large-scale text data, demonstrating the practical viability of incorporating language models into time-series forecasting without prohibitive computational overhead.

Several limitations warrant acknowledgment. The model’s performance exhibits sensitivity to prompt design, with approximately 10% variation across different formulations, introducing dependency on domain expertise for effective prompt engineering. Computational overhead (11.4 ms inference time) remains higher than lightweight baselines (3.1–6.2 ms), potentially limiting applications requiring sub-5 ms latency. Generalization to geographically distinct wind farms, extreme weather events, and significantly different capacity ranges requires further validation, as our experiments focus on four sites within similar regions (36–200 MW capacity). The current deterministic framework lacks uncertainty quantification capabilities increasingly demanded for risk-aware grid operations. Additionally, while experimental evidence supports semantic knowledge transfer, the extent of genuine semantic reasoning versus sophisticated feature extraction remains an open question requiring deeper investigation through counterfactual analyses and attention intervention studies.

Future research should address these limitations through automated prompt optimization techniques, computational acceleration via quantization and distillation, cross-regional validation experiments, integration of probabilistic forecasting capabilities, and rigorous semantic reasoning validation. Extending the framework to other renewable energy domains (e.g., solar power and hydropower), incorporating additional modalities (e.g., satellite imagery and numerical weather predictions), and developing online learning strategies for concept drift adaptation represent promising directions. Deployment in operational environments will provide crucial insights for practical refinement and broader adoption of LLM-based renewable energy forecasting systems.