2.1. Emerging Mixed Traffic Flows

The next generation simulation (NGSIM) dataset is a pivotal resource in the field of transportation, providing a wealth of authentic microscopic traffic data crucial for understanding micro-level traffic flow and car-following behavior, thereby advancing the development of traffic flow theory [

26,

27]. Over the past decade, numerous microscopic traffic studies have leveraged NGSIM’s traffic flow data, which includes urban roadway scenarios [

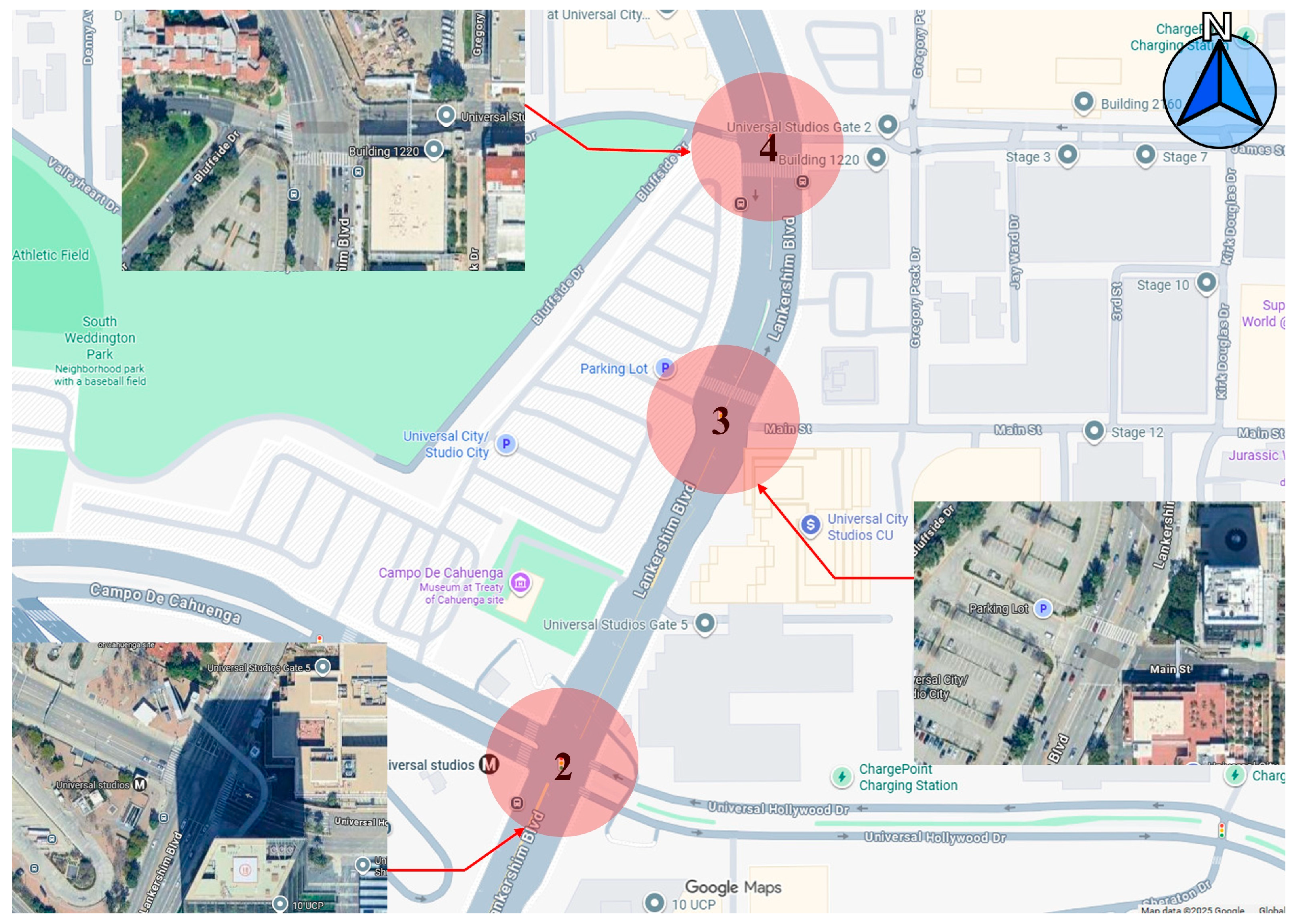

28]. In light of this, using the traffic flow data recorded on the Lankershim Boulevard segment from 8:30 to 8:45 as the data source, select intersections 2, 3, and 4 as the target intersections. Extract vehicle movement data within the region formed by these three intersections, and construct a road network model based on the trajectory data. The geographic location of the study area is shown in

Figure 1, while the geometric design information of each intersection used in the simulation model is presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

The traffic flow on this road segment consists of four vehicle types: motorcycles, trucks, buses, and cars, with the former three constituting a small proportion, accounting for only 4.63% of the total. To more accurately represent the actual operational conditions and traffic load within the intersection, after eliminating vehicle trajectory data with spatiotemporal inconsistencies, it is necessary to convert the volumes of motorcycles, trucks, and buses into equivalent traffic volumes using cars as the standard [

29]. The method for calculating equivalent traffic volumes is provided in Equation (1).

where

is the

of the objective vehicle type;

denotes the average time headway of objective vehicle type, s;

represents the average time headway of the vehicles following the objective vehicle type, s;

signifies the average time headway of a standard passenger car, s; and

is the average time headway of the vehicles following a standard car, s.

Based on this, after obtaining the traffic volume during peak periods at the target area’s intersections, the traffic volume is scaled up by 400% to derive the peak hour traffic flow for the intersections. The traffic flow and directionality for intersection 2, intersection 3, and intersection 4 during peak hours are presented in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5, respectively.

Upon determining the directional traffic flows at each intersection approach, vehicle routes were assigned based on real-world trajectory data. The specific origin-destination routes are detailed in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8. For all defined routes, the departure lane parameter “departlane” was set to “free,” thereby allowing each vehicle to select the fastest available lane at the moment of insertion.

The MPRs of CAVs were set at 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%, progressively integrating CAVs into the traffic flow originally composed solely of HDVs [

30,

31]. Based on the society of automotive engineers (SAE) classification of automation levels, current market-available CAVs predominantly operate at L1 and L2, relying primarily on onboard sensors such as cameras, radar, and lidar to acquire information about their own state and surrounding environment [

32,

33,

34]. Accordingly, CAV sensing systems could be categorized into vision-based and lidar-based systems. Radar is an indispensable component in both vision-based and lidar-based configurations, and could be further classified into short-range radar (0.15–30 m), medium-range radar (1–100 m), and long-range radar (10–250 m) [

35]. Based on these radar detection ranges, CAVs in emerging mixed traffic flows were divided into three types, CAV-S1, CAV-S2, and CAV-S3, corresponding to radar detection ranges of 30 m, 60 m, and 100 m, respectively, with the assumption that longitudinal target detection by CAVs relies on their equipped radar [

36]. As previously stated, CAVs in the emerging mixed traffic flow exhibit varying levels of automation, and the performance differences of the onboard radar systems on which they rely are manifested not only in maximum detection range but also in sensing accuracy. In prior studies, longitudinal ranging errors of onboard radar systems have been reported to reach or exceed 2 m, 5 m, and even 10 m [

37,

38,

39]. On this basis, the radar detection accuracy for CAV-S1, CAV-S2, and CAV-S3 was set with error margins of [−2, +2] m, [−5, +5] m, and [−10, +10] m, respectively, thereby achieving the perception asymmetry among different CAVs. Additionally, the proportions of CAV-S1, CAV-S2, and CAV-S3 within the CAV population were configured as 45%, 35%, and 20%, respectively, to complete the setup of the emerging mixed traffic flow [

19,

20]. These proportions do not represent market penetration rates, but instead reflect the practical assumption that vehicles with shorter sensing ranges correspond to lower-cost advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) configurations and are therefore more common in the market, whereas vehicles equipped with medium- and long-range sensing capabilities rely on more expensive sensors and thus constitute smaller shares of CAVs.

On the other hand, when simulating regional traffic operations by inputting extracted traffic flow data into SUMO, the intelligent driver model (IDM) and cooperative adaptive cruise control (CACC) were employed as the car-following models for HDVs and CAVs, respectively. Specifically, key parameters in the car-following models, including maximum acceleration (acc), maximum deceleration (dec), maximum speed (spe), and the minimum gap maintained at a standstill (gap), were calibrated based on the actual operating conditions of the vehicles. More precisely, the expected values of maximum acceleration, maximum deceleration, and maximum speed at each intersection were adopted as the acc, dec, and spe parameters for both IDM and CACC [

40]. For the calibration of the gap parameter, vehicle trajectory segments were extracted according to commonly accepted minimum safe TTC ranges for HDVs and CAVs. TTC values between 1.0 and 1.5 s for HDVs and between 0.9 and 1.0 s for CAVs represent typical lower-bound safe following conditions observed in previous studies, where drivers or automated systems maintain the smallest stable spacing. Therefore, trajectory data falling within these TTC intervals were used to estimate the corresponding steady-state spacing and to derive the gap parameters for IDM and CACC. The expected values for the parameters to be calibrated at each intersection are presented in

Table 9.

Based on the actual operating conditions of vehicles in the study area, the car-following model parameters were calibrated as follows: acc and dec were set to 4.83 m/s

2, and spe was set to 16.69 m/s. Additionally, the gap was established at 6.0 m for IDM and 5.0 m for CACC. To account for the lateral maneuvers exhibited by both HDVs and CAVs during real-world operation, the default lane-changing model LC2013 implemented in SUMO is adopted [

41]. The physical attributes and kinematic characteristics of each vehicle type are presented in

Table 10, which indicates that, apart from differences in control strategies and perception capabilities, no discrepancies exist in the inherent vehicle parameters across different vehicle types. Furthermore, all vehicles are modeled as gasoline-powered passenger cars compliant with Euro 4 emission standards, with fuel consumption derived from the emission factors provided by the handbook emission factors for road transport (HBEFA) version 3.1 [

42].

2.2. Control Strategies for Intersections and Vehicles

2.2.1. Signal Timing for the Intersection

To achieve green wave coordinated control among intersections 2, 3, and 4, signal timing schemes were designed for each intersection based on the traffic flow direction, number of lanes, and lane functions at their respective approaches [

43,

44,

45]. The resulting fixed signal timing schemes for each intersection are presented in

Table 11.

From

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5, it could be observed that the NBAs of the intersections constitute the dominant inflow paths, with a substantial number of vehicles entering the study area from the NBA of intersection 4 and exiting mainly through the SBA of intersection 2. Given that this directional flow represents the primary movement within the network and contributes most significantly to overall traffic demand, the green-wave coordination is designed along the NBAs to improve progression efficiency for these major-stream vehicles. The phase splits at each intersection were first determined using the Webster signal timing method, in which the optimal cycle length and the green–yellow allocations for each phase were calculated based on the observed approach volumes and lane configurations derived from the NGSIM trajectory data. The average vehicle speed at the NBA of intersection 4 is 5.56 m/s, while that at the NBA of intersection 3 is 11.11 m/s. For intersection 2, the average vehicle speed at both the NBA and SBA is 8.33 m/s. Additionally, the recorded segment length of the NBA at intersection 4 is 100 m, the distance between the center points of intersection 4 and intersection 3 is 500 m, and the distance between the center points of intersection 3 and intersection 2 is 650 m. After the phase splits and cycle lengths were obtained through the Webster method, the offsets between consecutive intersections were then assigned according to these distances and the prevailing average speeds along the north–south direction. Under these physical road conditions, traffic demand characteristics, and prevailing speeds, the resulting signal timing configuration for green wave coordination targeting the north-to-south traffic flow is illustrated in

Figure 2.

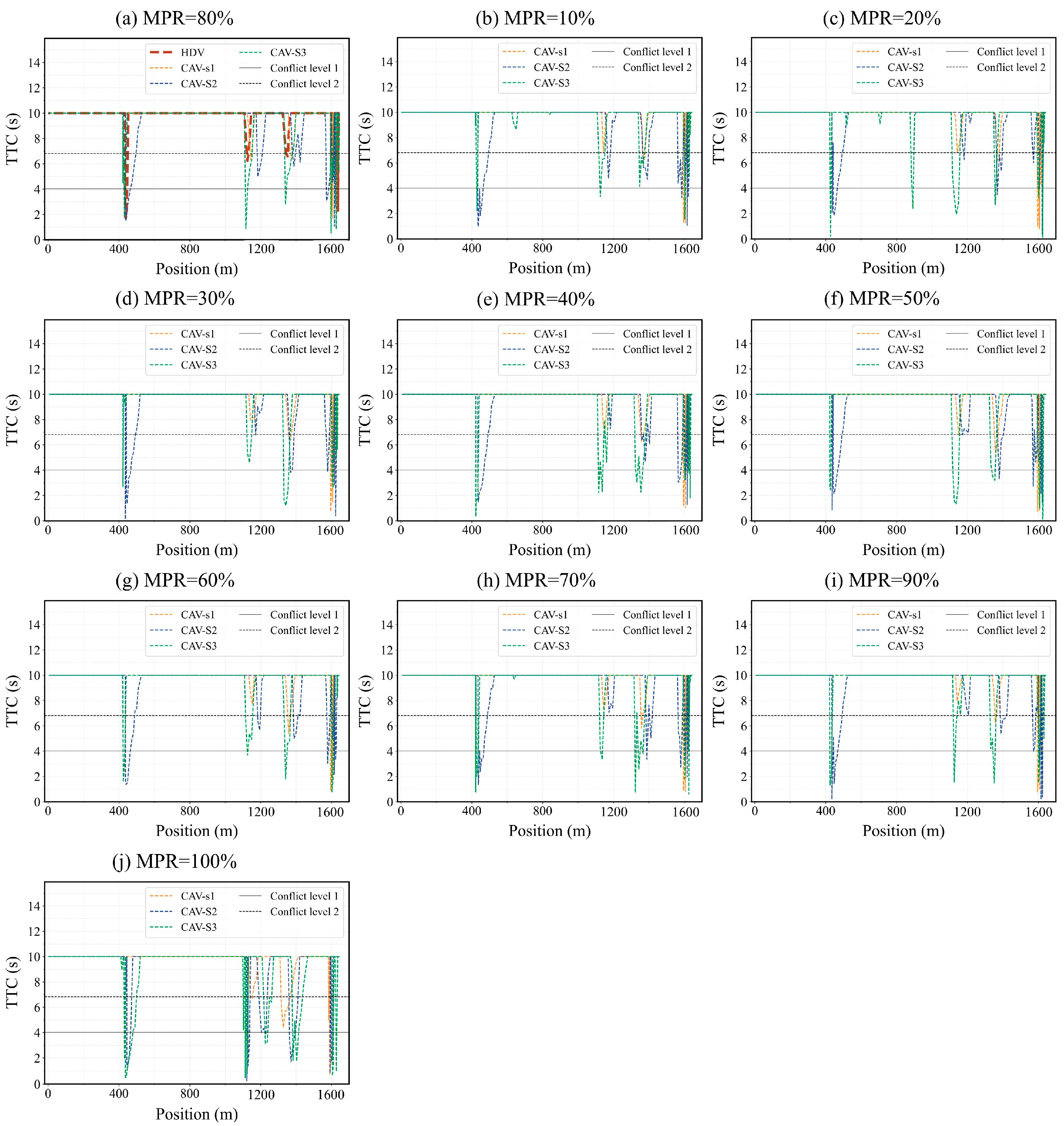

2.2.2. Evaluation of the Crash Risk for Vehicles

Prior to implementing control strategies for CAVs in emerging mixed traffic flows, it is essential to ascertain the current safety status of the target vehicle, determine the presence of potential conflicts, and evaluate the severity of crash risks to provide a foundation for vehicle control decisions. The application of the PnG to CAVs fundamentally involves controlling their longitudinal speed. For conflicts that may arise due to longitudinal speed variations, TTC is one of the most commonly used surrogate safety measures in such scenarios [

46,

47]. Furthermore, the calculation of TTC is straightforward, and the required parameters are relatively easy to obtain, making it well-suited for processing large-scale data or prolonged applications. Consequently, TTC was selected as the evaluation metric for the crash risk to characterize the safety status of vehicles within the study area, with its mathematical expression provided in Equation (2).

where

is the position of the leading vehicle;

denotes the position of the following vehicle;

represents the velocity of the leading vehicle;

signifies the velocity of the following vehicle; and

is the length of the vehicle.

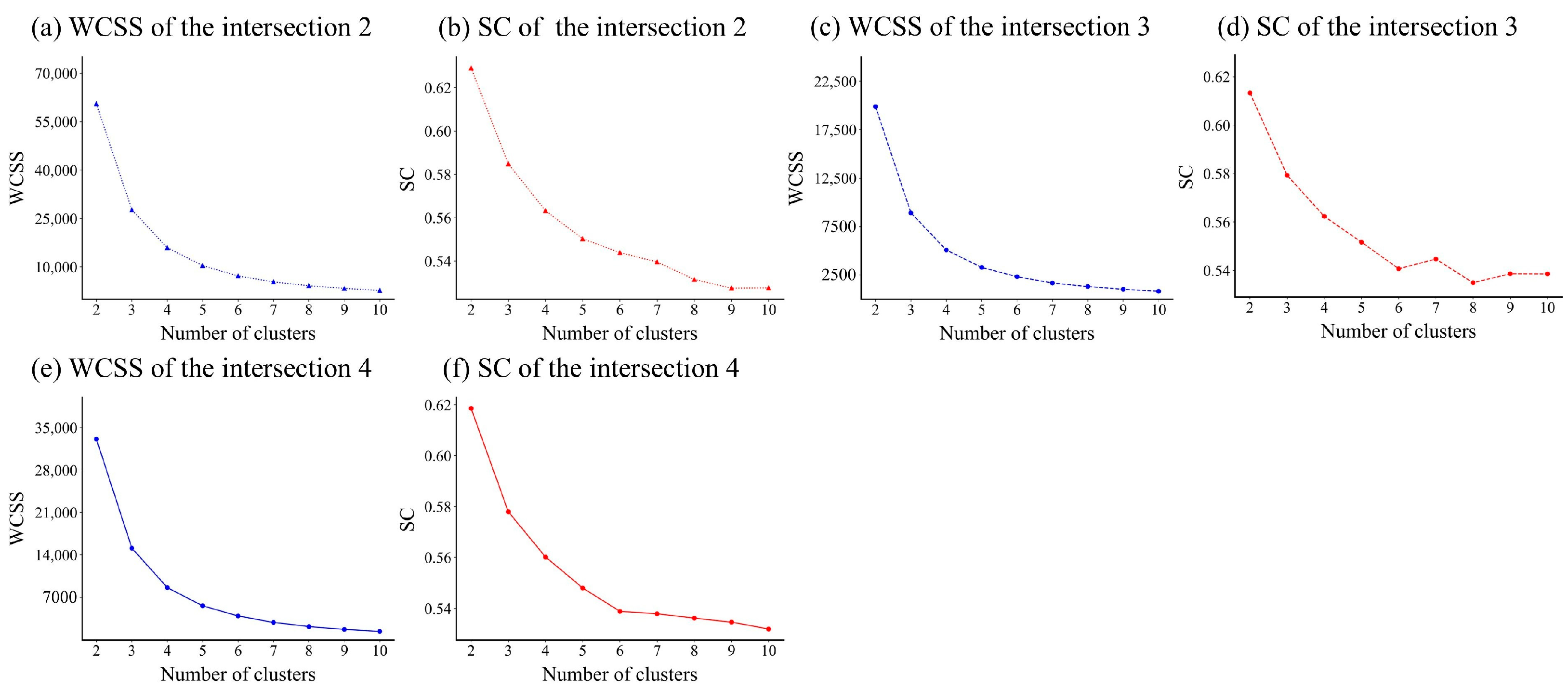

After calculating the TTC values within the regions of each intersection and filtering for data within the range of [

1,

10], the distribution characteristics of TTC at each intersection were analyzed using clustering methods. Specifically, the elbow method and silhouette coefficient (SC) were employed to determine the optimal number of clusters for intersections 2, 3, and 4. The elbow method identifies the optimal number of clusters by locating the inflection point (elbow) where the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) ceases to decrease substantially, whereas the silhouette coefficient (SC) method favors the cluster number that maximizes the average silhouette score. The search range for the number of clusters was set to [

2,

10].

For the TTC data collected at Intersection 2, a pronounced change in the rate of WCSS reduction was observed when the cluster number reached 3. Beyond this point, further increases in the number of clusters yielded progressively smaller reductions in WCSS, while the silhouette coefficient exhibited a consistent declining trend with increasing cluster numbers. Consequently, the optimal number of clusters for the TTC distribution at Intersection 2 was determined to be 3, as illustrated in

Figure 3a,b. A similar analysis was performed for Intersection 3, with results shown in

Figure 3c,d, again yielding an optimal cluster number of 3. The corresponding results for Intersection 4 are presented in

Figure 3e,f, where the optimal number of clusters was likewise found to be 3.

Subsequently, a gaussian mixture model (GMM) was applied to cluster the TTC data for these intersections, with the resulting clustering outcomes presented in

Table 12,

Table 13 and

Table 14.

When the TTC falls within cluster 1, it indicates a significant crash risk, designated as conflict level 1. At this level, vehicles should decelerate or, if necessary, change lanes to avoid rear-end crashes. Notably, the upper limit of conflict level 1 at intersection 2 is the lowest, at 3.95 s, primarily due to the high traffic volume, elevated traffic flow density, and reduced inter-vehicle spacing at this intersection. Cluster 2 signifies the presence of a conflict with a high likelihood of further escalation, denoted as conflict level 2, where acceleration maneuvers should be executed with caution to avoid excessive intensity. In contrast, cluster 3 corresponds to larger TTC values, indicating greater flexibility for speed adjustments, and is classified as conflict level 3. When TTC exceeds 10 s, a conflict with the leading vehicle persists, but the driver or control system has sufficient space to adjust the vehicle’s speed, allowing maintenance of the current speed or acceleration, thus designated as conflict level 4. It should be noted that TTC values exceeding 10 s are not interpreted as absolute safety; rather, they indicate that the vehicle has sufficient longitudinal spacing under normal conditions. When TTC decreases and the vehicle transitions into lower conflict levels, the corresponding control strategies are activated to ensure that safety is continuously maintained.

2.2.3. Speed Planning for Vehicles

- (1)

PnG control under the green wave

For a CAV entering the study area from the NBA of intersection 4 and intending to exit via the SBA of intersection 2, when it first appears at the NBA of an intersection, assuming no leading vehicle in its lane, if it arrives at the stop line at the area’s average speed during the green indication of the corresponding signal phase, it is deemed likely to be within the green wave. Furthermore, if the vehicle is within the green wave and its initial appearance at the NBA coincides with the green indication, and there is either no leading vehicle, no conflict, or the TTC is at conflict level 2 or higher, the area’s average speed is adopted as the average speed for the vehicle’s PnG mode. The acceleration is set to the optimal value of 0.61 m/s

2 derived by Tian et al. [

48], while the gliding deceleration is established at 0.16 m/s

2, thereby simulating the condition in which the engine is decoupled from the powertrain and the vehicle glides purely by inertia, achieving zero fuel consumption during this phase [

17].

On the other hand, when a vehicle is within the green wave but initially appears at the NBA before the onset of the green indication, its average speed in the PnG mode should enable it to traverse the intersection within the first 30% of the green indication, provided there are no leading vehicles, no conflicts, or a conflict level of 4 [

18]. The specific calculation method is presented in Equation (3).

where

is the average speed of the PnG mode, m/s;

denote the position where the vehicle first appeared at the NBA, m;

represents the position of the stop line for the NBA, m;

signifies the time where the vehicle first appeared at the NBA;

is the start time of the green light;

denotes the length of the green light, s; and

represents the average speed of the area where the vehicle is located, m/s.

Conversely, when a conflict exists and the conflict level exceeds 1, the vehicle could determine the average speed for the PnG mode based on its current conflict level. In contrast, if the vehicle is in conflict level 1, it should fully adhere to the control of CACC, maintaining sufficient spacing from the leading vehicle to increase the TTC and thereby improve the vehicle’s safety state. Specifically, if the vehicle is in conflict level 2, it is required to pass through the intersection within the first 90% of the green indication, with the calculation process for the average speed of its PnG mode outlined as follows:

For CAVs in conflict level 3, the vehicle is scheduled to traverse the intersection within the first 60% of the green indication, with the computation of its PnG mode average speed detailed in Equation (5).

It should be noted that the thresholds of 30%, 60%, and 90% of the green phase are not derived from existing PnG or signal-coordination literature. Instead, these values are purposely designed within the proposed control framework to reflect the perception asymmetry among different CAV types. CAVs equipped with larger detection ranges could assess traffic conditions and the leading vehicle earlier, allowing them to safely activate the PnG mode sooner. Assigning smaller green-window requirements (e.g., 30%) enables these CAVs to make fuller use of the green-wave progression and pass the intersection efficiently. In contrast, CAVs with shorter detection ranges require more time to verify safety conditions before accelerating, and thus larger thresholds (60% or 90%) ensure that the planned traversal remains feasible and safe. Therefore, the progressive thresholds serve as a graded control mechanism aligned with the sensing capabilities of each CAV type.

- (2)

PnG control outside the green wave

When CAVs are not within the green wave, the activation of the PnG mode should still adhere to safety constraints. In scenarios where there is no leading vehicle, no conflict exists, or the conflict level is 2 or higher, the vehicle may adopt the average speed of the current area as the PnG mode’s average speed to perform acceleration and deceleration maneuvers. Conversely, for CAVs where the TTC does not meet safety constraints, the vehicle should operate under CACC to maintain a safe distance from the leading vehicle, prohibiting the activation of the PnG mode to avoid crashes due to acceleration.

On the other hand, for HDVs operating under the IDM, only the desired speed is specified without additional control measures. Specifically, when an HDV is traveling at the NBA of intersection 4, its desired speed is set to 5.56 m/s. When the HDV navigates the road segment between intersection 4 and intersection 3 in the southbound direction, its desired speed is set to 11.11 m/s. For all other road segments, the desired speed is uniformly set to 8.83 m/s. The desired speeds of HDVs on each segment were obtained from the empirical trajectory dataset used to construct the network. Specifically, the average observed speed of HDVs on each segment was calculated and adopted as the desired speed, allowing the simulated HDVs to more closely reflect the driving behavior patterns and traffic operation characteristics observed in the real-world data.