Machine Learning Framework for Automated Transistor-Level Analogue and Digital Circuit Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1.

- How effectively can GE generate functional transistor-level circuit designs while recognising and exploiting domain-level symmetries?

- RQ2.

- What is the impact of multi-objective evaluation and objective-induced symmetries (e.g., logic thresholds) on optimisation dynamics and the emergence or breaking of symmetric circuit forms?

- RQ3.

- Can the proposed automated system consistently generate competitive or superior analogue/digital circuits by balancing symmetry preservation and asymmetry-driven innovation across technology nodes?

2. Evolutionary Algorithm (EA)

2.1. Grammatical Evolution (GE)

2.2. EA in Circuit Design

3. Transistor-Level Design and Automation Using SKILL

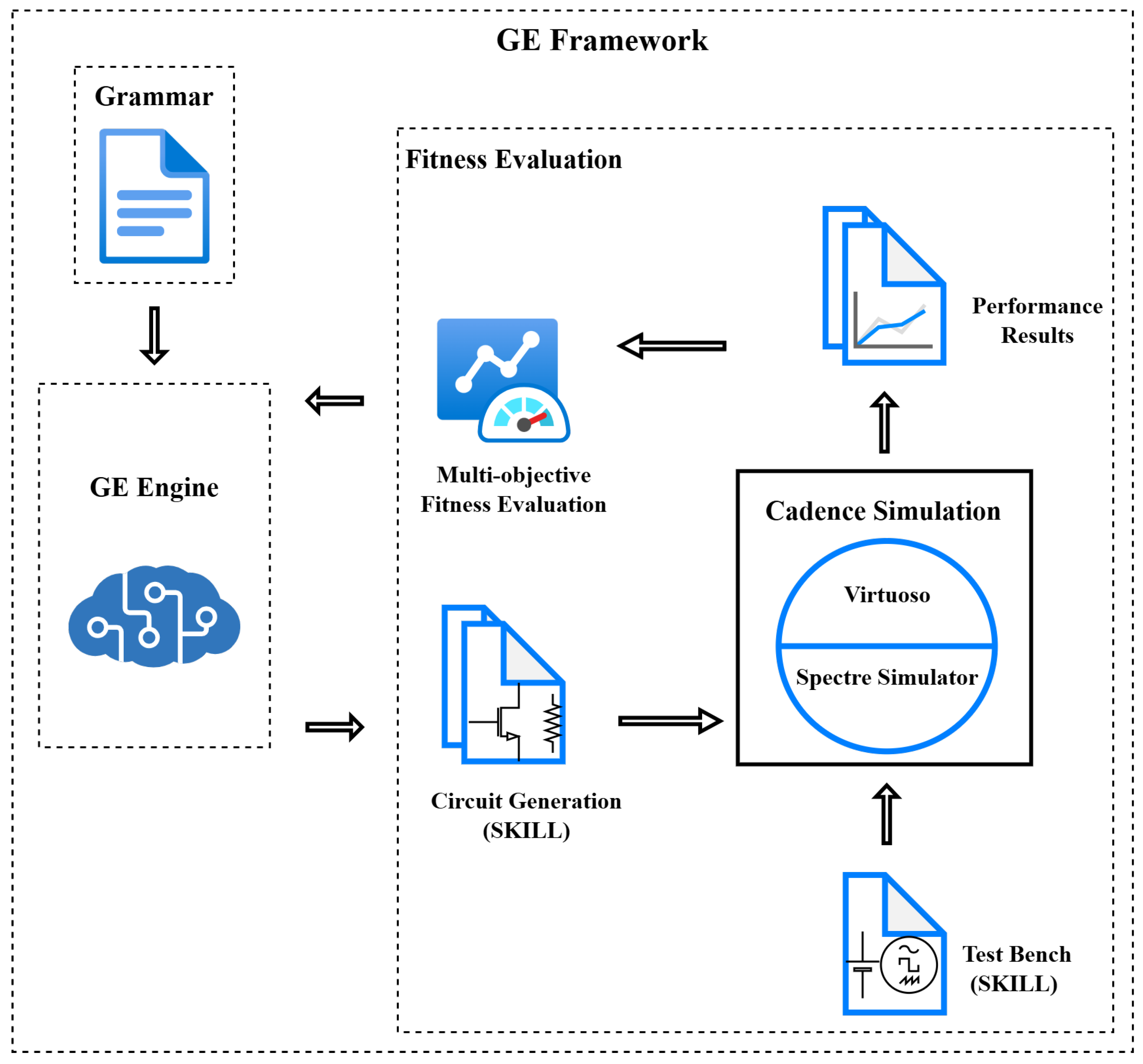

4. Methodology

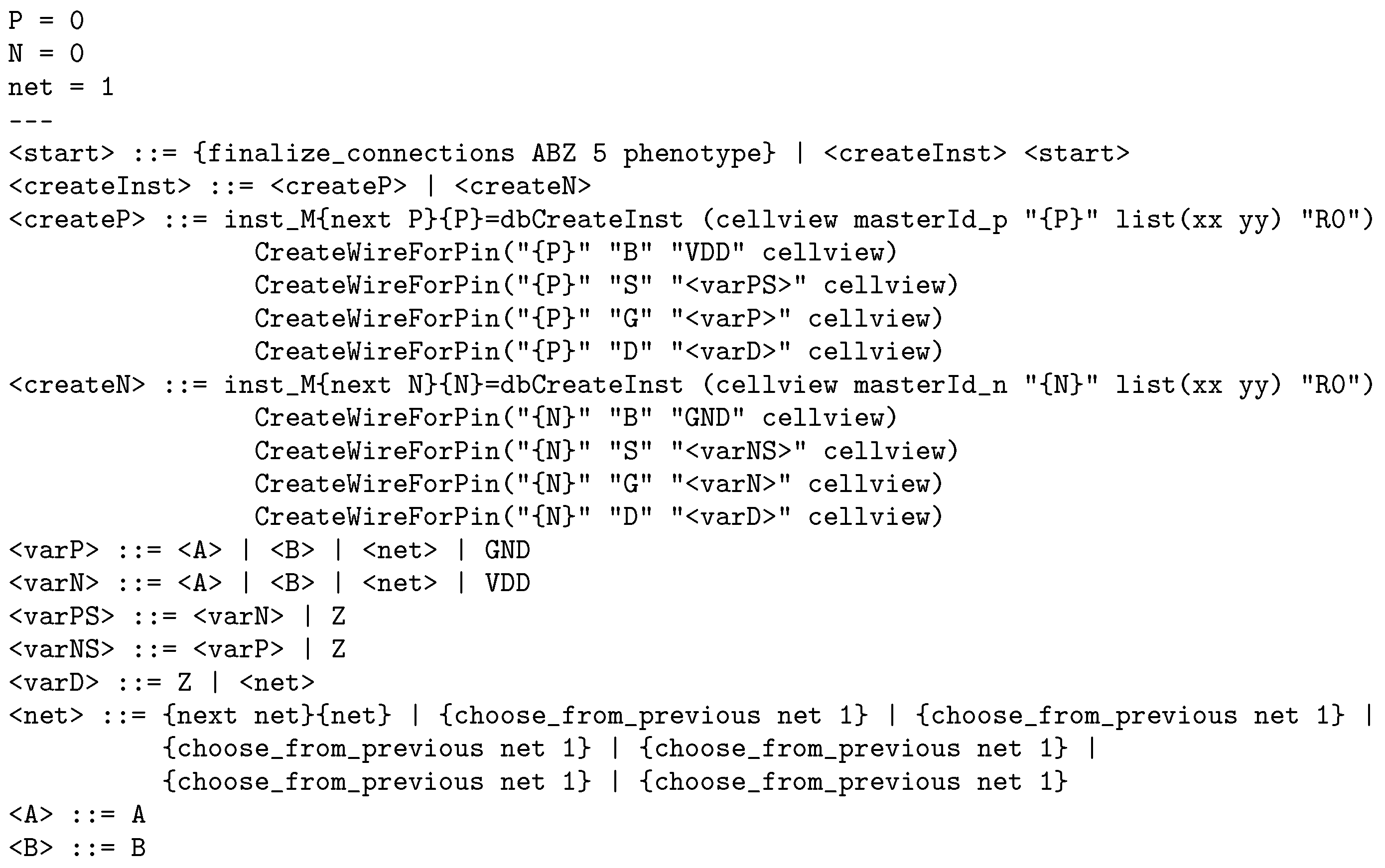

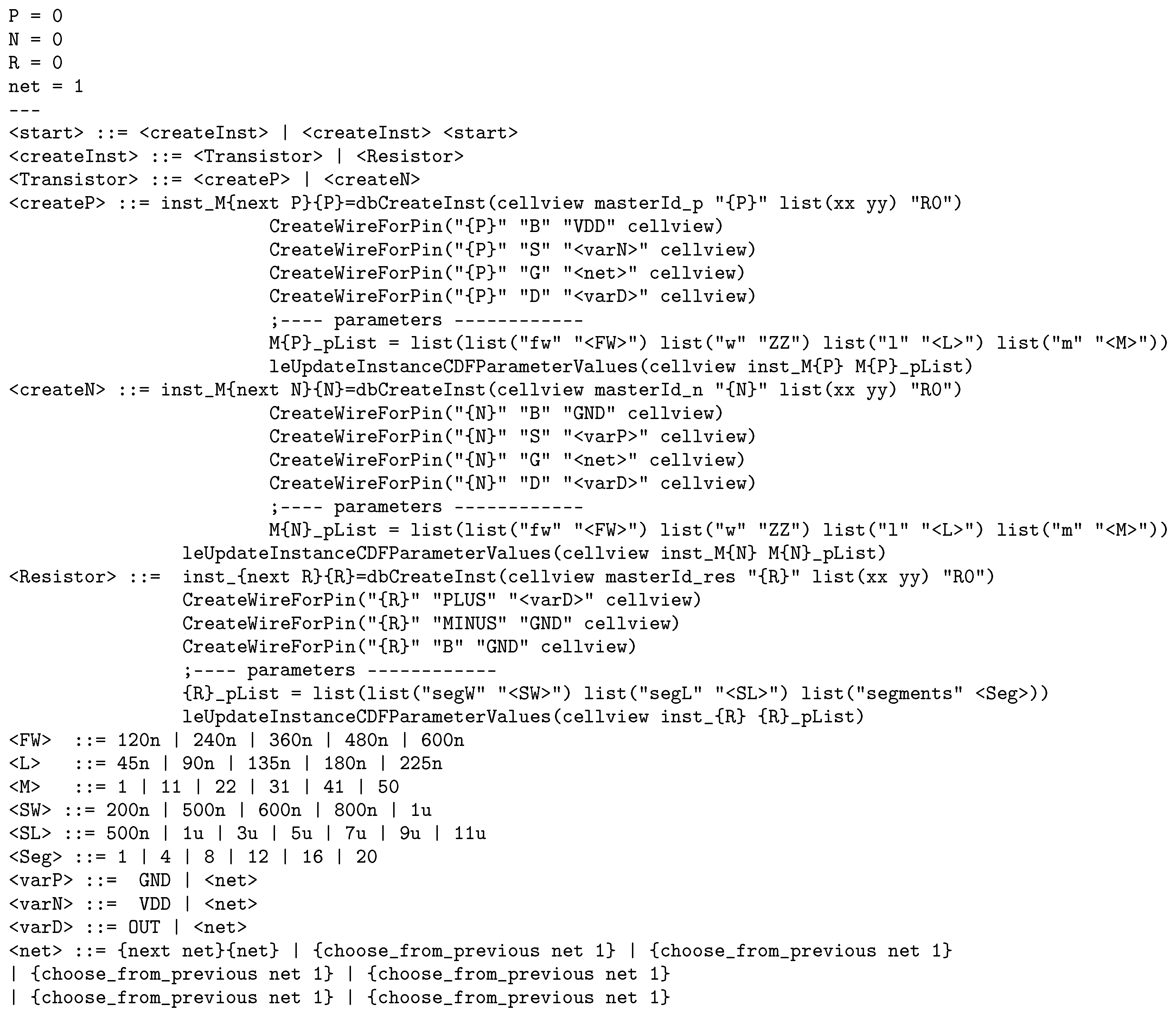

4.1. Digital Circuit Grammar

- Dynamic variable initialisation: Variables that are updated dynamically are initialised using the equality operator (=) to ensure consistent naming and reuse.

- Core BNF components:

- (a)

- Start symbol: The entry point of the grammar, typically the leftmost non-terminal (e.g., <start>).

- (b)

- Production rules: Define how non-terminal symbols are expanded into terminals and other non-terminals. For example, <createInst> ::= <createP>|<createN>.

- (c)

- Terminals: Leaf symbols that appear in the final program, such as A, B, GND, VDD, and Z.

- (d)

- Non-terminals: Intermediate symbols used to structure the grammar (e.g., <createInst>).

- AFs: Conceptually similar to semantic functions, these functions guide both initialisation and dynamic phenotype construction. They include the following:

- (a)

- Phenotype access functions: Ensure correct finalisation and integration of generated instances (e.g., {finalize_connections}), typically consuming multiple codons.

- (b)

- Attribute variables: Track state information such as transistor indices or net counts without consuming codons (e.g., {Next}).

- (c)

- Codon-consuming AFs: Functions like {choose_from_previous} allow reuse of previously defined nodes or nets, adding flexibility while consuming codons.

- (d)

- Substitution AFs: Inline substitution of dynamic variable values at specific points in the phenotype (e.g., {P}).

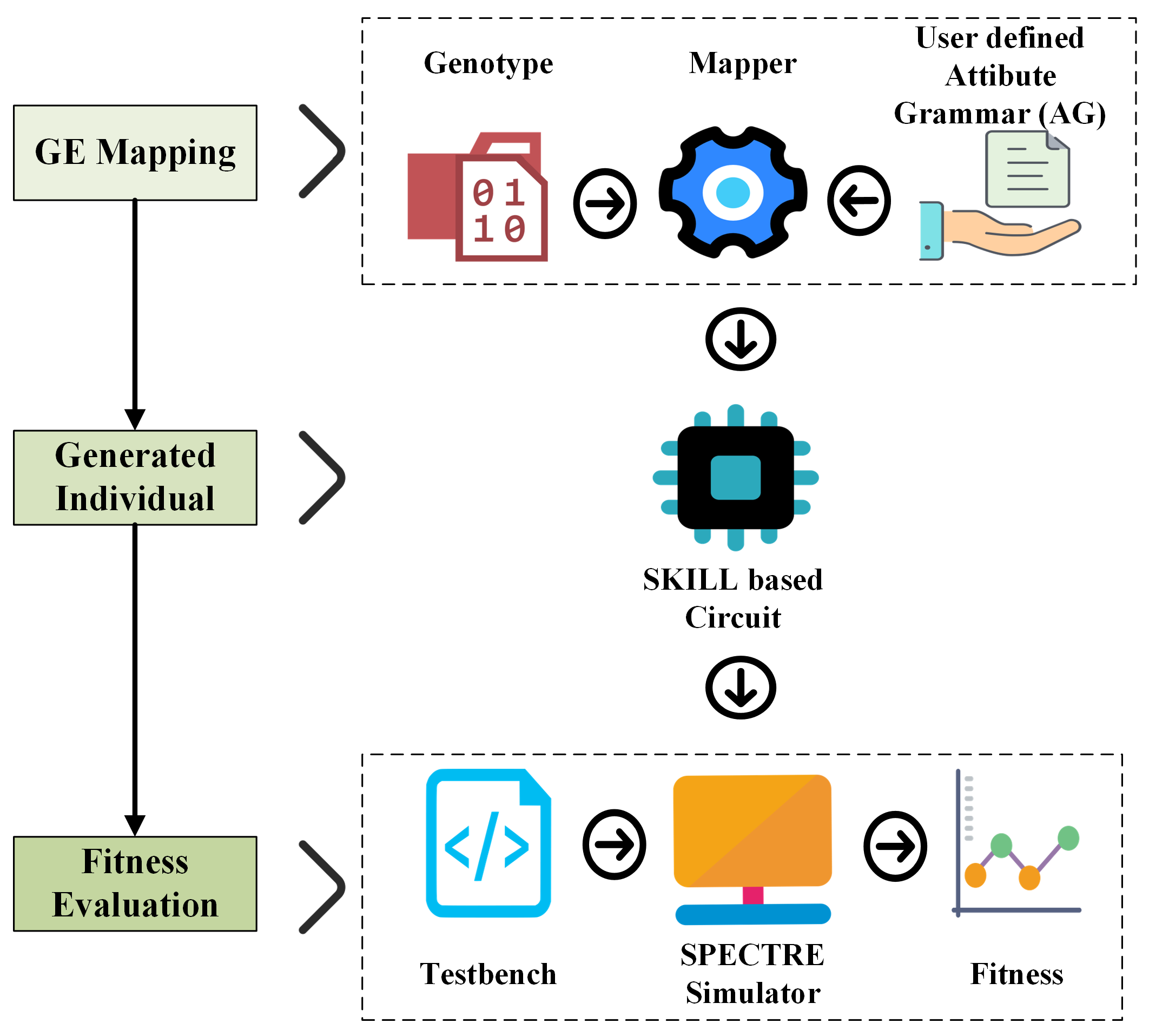

4.2. Genotype-to-Phenotype Decoding Example

| 61, 20, 12, 23, 16, 22, 49, 7, 26, 31, 21, 171, 31, 57, 99, 110, 34, 76, 120, 156, 188, 220, 10, 15, 41, 40, 47, 125, 110, 74, 5 |

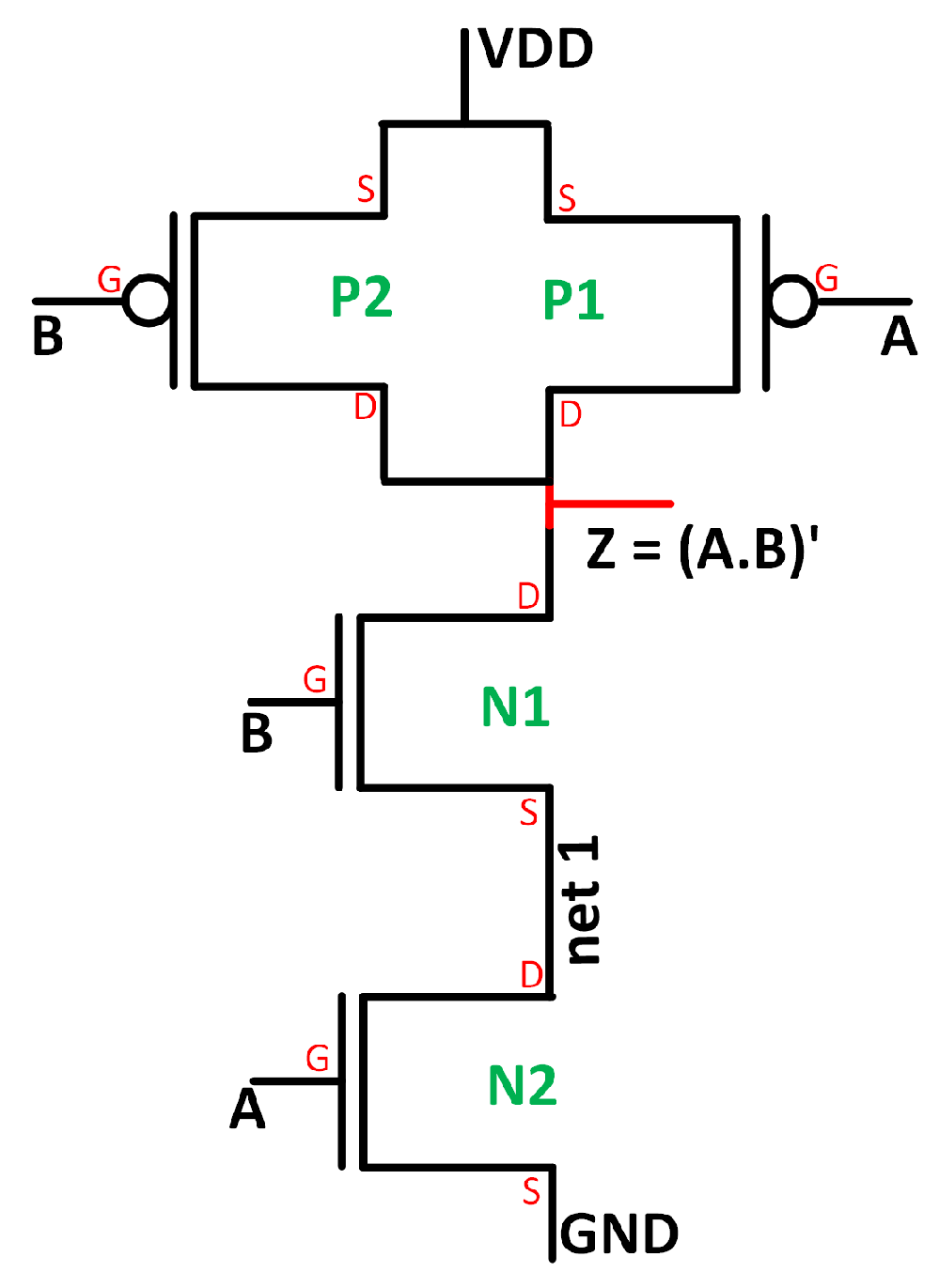

- Step 1.

- Mapping begins with <start>.

- Step 2.

- The first codon is picked, and a Modulo (MOD) operation is performed with 2, since there are two options in this production rule. Therefore, we calculate 61% 2, which is one. This chooses the <createInst> <start> rule. Note that execution proceeds from left to right.

- Step 3.

- 20% 2; choose <createP> to create a PMOS transistor.

- Step 4.

- One attribute variable AF and six substitution AFs dynamically assign values to P. {next P} updates the index (e.g., P0 to P1), and {P} substitutes the updated index. No codons are consumed. Then, non-terminals <varPS>, <varP>, and <varD> are executed one by one.

- Step 5.

- 12% 2 = 0; choose <varN>.

- Step 6.

- 23% 4 = 3; choose terminal VDD.

- Step 7.

- 16% 4 = 0; choose <A>, which yields A.

- Step 8.

- 22% 2 = 0; choose terminal Z.

- Step 9.

- Execution returns to <start>. 49% 2 = 1; choose <createInst> <start>.

- Step 10.

- 7% 2 = 1; choose <createN> to create an NMOS transistor.

- Step 11.

- Similarly to Step 4, variable N is dynamically assigned using attribute and substitution AFs.

- Step 12.

- 26% 2 = 0; choose <varP>.

- Step 13.

- 31% 4 = 3; choose terminal GND.

- Step 14.

- 21% 4 = 1; choose <B>, which yields B.

- Step 15.

- 171% 2 = 1; choose non-terminal <net>.

- Step 16.

- 31% 7 = 3; choose {choose_from_previous}, which connects to net1, as net is initialised as 1.

- Steps 17–22.

- These steps repeat the logic from Steps 9 to 16, using codons 57, 99, 110, 34, 76, 120, and 156 to create an NMOS transistor connected to net1, A, and Z.

- Step 23.

- <start> is executed again. Then 188% 2 = 0; choose {finalize_connection}.

- Step 24.

- {finalize_connection} consumes five codons (220, 10, 15, 41, and 40) and creates a PMOS transistor with Source, Gate, and Drain connected to VDD, B, and Z.

4.3. Analogue Circuit Grammar

4.4. Fitness Function

- The first objective, , measures how accurately the output of the evolved circuit matches that of a reference “gold” circuit—a version designed using conventional logic (CMOS, TGL, and GDI). Essentially, it captures the circuit’s error by comparing its outputs bit by bit:Here, N represents the total number of binary bits tested. The function 1(·) is an indicator that returns 1 whenever the evolved circuit’s output bit differs from the corresponding bit in the gold circuit’s output and 0 when they match.

- The second objective, , estimates the circuit’s area by simply counting how many transistors are used in the evolved design:Here, is the total number of transistors in the evolved circuit.

- The third objective () estimates the evolved circuit’s total average power consumption, calculated as follows:Here, and are the instantaneous voltage and current, respectively, and T is the total simulation time.

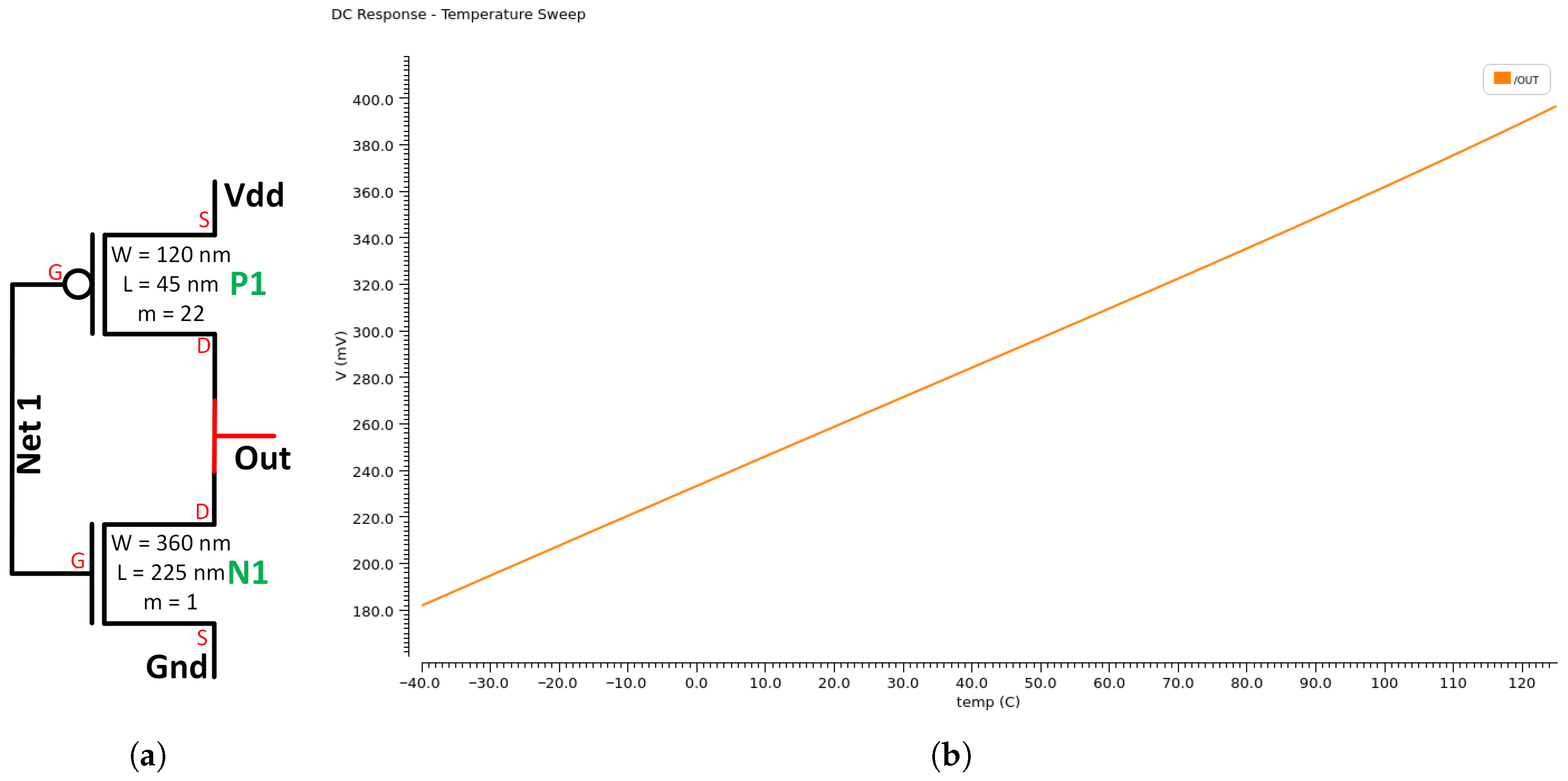

- The first objective, , represents how much the sensor’s output (typically voltage or current) changes in response to a change in temperature. This is usually expressed as the output change per degree Celsius (e.g., mV/°C) and is given byHere, is the temperature at step i, given by is the temperature step size; is the measured voltage at temperature ; and N is the total number of steps, given by , where and are the maximum and minimum temperatures.

- The second objective, , is the INL, which measures the deviation of the sensor’s actual output from an ideal linear response across the temperature range. It indicates how accurately the sensor maintains a straight-line relationship between temperature and output and is given byHere, is the intercept of the best-fit line and is the slope of the best-fit line.

- The third objective, , estimates the static power consumption of the temperature sensor:Here, V represents the supply voltage and I represents the direct current.

- Finally, estimates the actual area in terms of the number of devices in the circuit and the number of parameters associated with each device:Here, is the number of devices in the design; is the number of parameters of the device i; i is the device counter; and l is the parameters’ counter.

4.5. Experimental Setup, Tools, and Evolutionary Parameters

5. Results and Evaluation

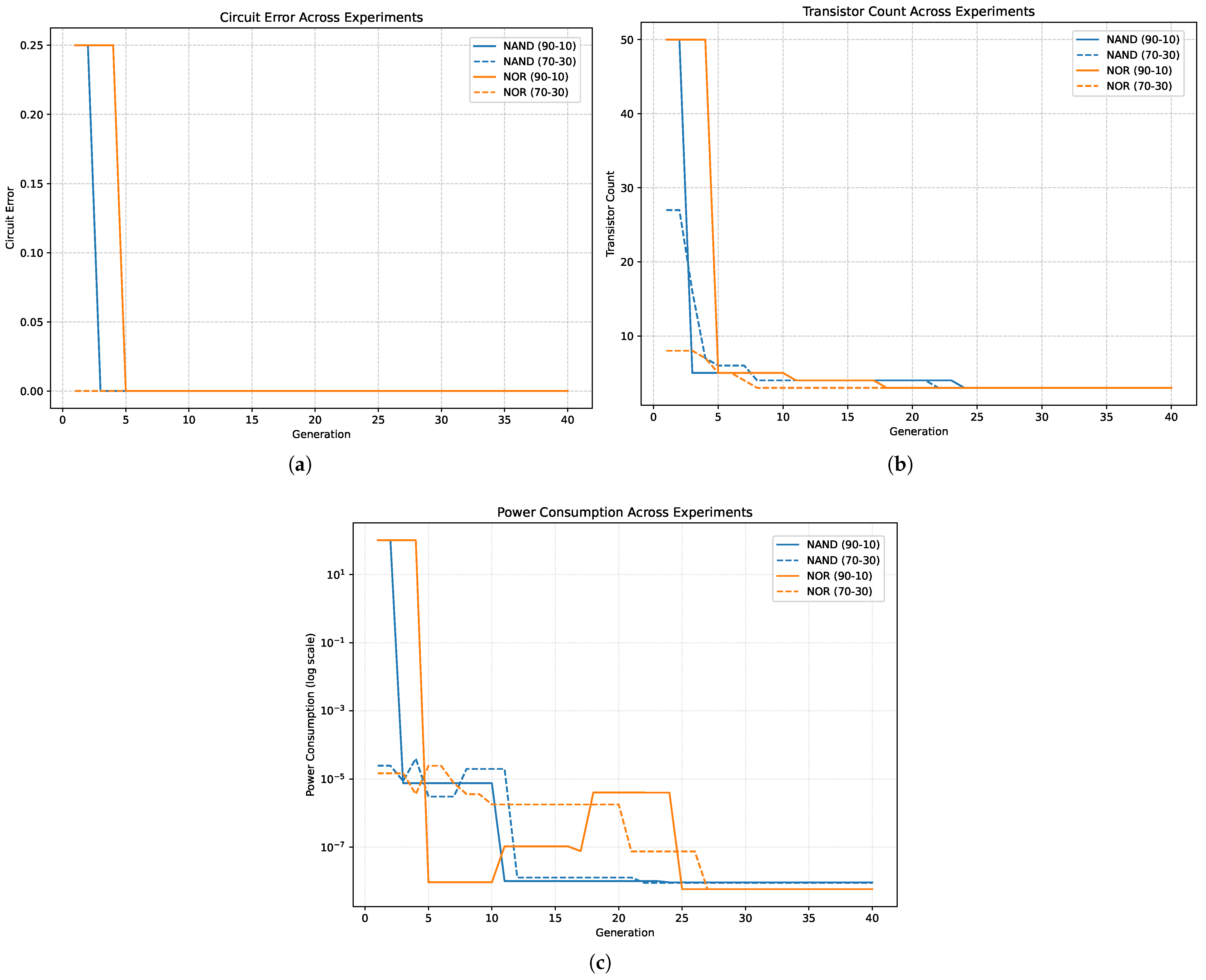

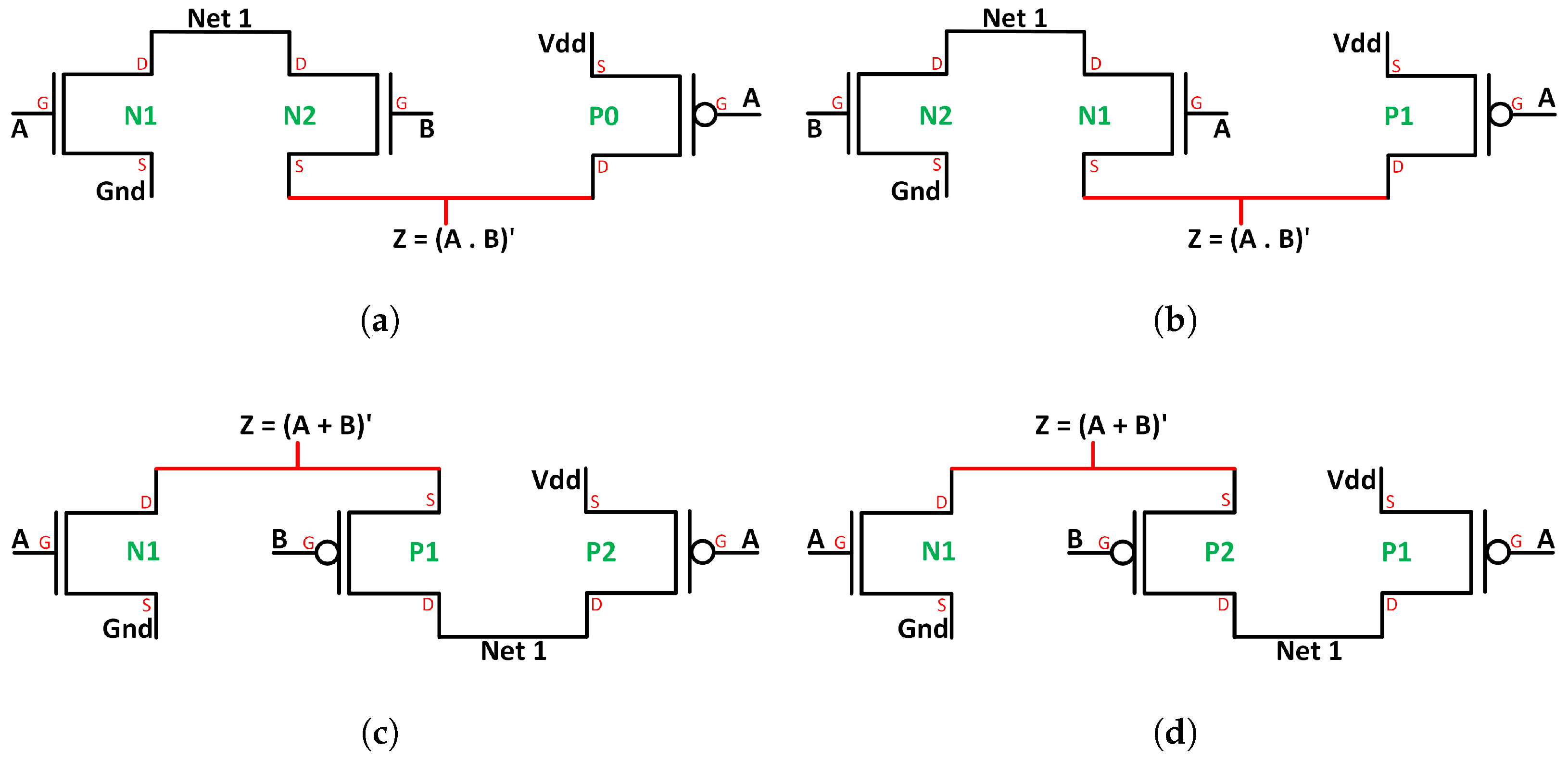

5.1. Evolution of NAND/NOR (Digital Circuit)

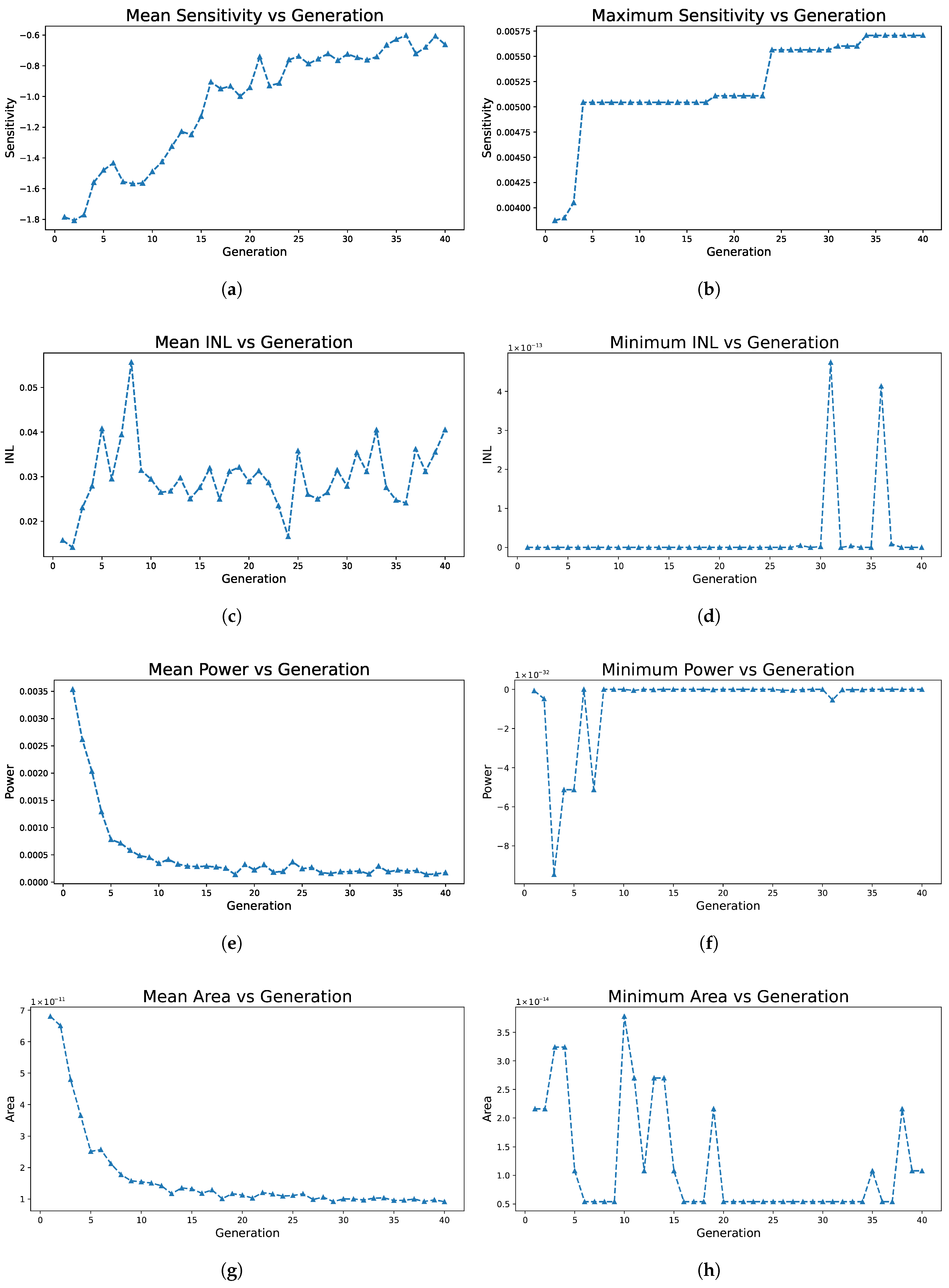

5.2. Evolution of Temperature Sensor (Analogue Circuit)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Razavi, B. Design of Analog CMOS Integrated Circuits; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rabaey, J.M.; Chandrakasan, A.; Nikolic, B. Digital Integrated Circuits: A Design Perspective, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nassif, S.R. Modeling and analysis of manufacturing variations. In Proceedings of the Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), San Diego, CA, USA, 9–9 May 2001; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Borkar, S. Design challenges of technology scaling. IEEE Micro 1999, 19, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semiconductor, F. CMOS, the Ideal Logic Family. Application Note 77. 1983. Available online: https://shrubbery.net/~heas/willem/PDF/NSC/AN/AN-77.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Al-Assadi, W.; Jayasumana, A.P.; Malaiya, Y.K. Pass-transistor logic design. Int. J. Electron. Theor. Exp. 1991, 70, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenshtein, A.; Fish, A.; Wagner, I.A. Gate-diffusion input (GDI): A power-efficient method for digital combinatorial circuits. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2003, 10, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, D.P.; Litovski, V.B. Fault models of CMOS transmission gate. Int. J. Electron. 1991, 71, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, D.; Kozen, D.; Tiuryn, J. Dynamic logic. ACM SIGACT News 2001, 32, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, D.A.; Martin, K. Analog Integrated Circuit Design; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Laker, K.R.; Sansen, W.M.C. Design of Analog Integrated Circuits and Systems; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.; Collins, J.; Neill, M.O. Grammatical evolution: Evolving programs for an arbitrary language. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Genetic Programming, Paris, France, 14–15 April 1998; Banzhaf, W., Poli, R., Schoenauer, M., Fogarty, T.C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bäck, T.; Fogel, D.B.; Michalewicz, Z. Handbook of Evolutionary Computation; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Genetic algorithms. Sci. Am. 1992, 267, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koza, J.R. Genetic Programming: On the Programming of Computers by Means of Natural Selection; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.; Tetteh, M.; McEllin, J.; Mota-Dias, D.; Conway, R.; Naredo, E. ADDC: Automatic design of digital circuit. In Genetic Algorithms; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tetteh, M.; Dias, D.M.; Ryan, C. Grammatical evolution of complex digital circuits in SystemVerilog. SN Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, B.; McEllin, J.; Sarma, R.; Youssef, A.; Dias, D.; Ryan, C. Grammatical Evolution of Synthesizable Finite State Machine-Based Behavioural Level Hardware Description Language Codes. In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence—ECTA. INSTICC, Porto, Portugal, 20–22 November 2024; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2024; pp. 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blickle, T. Tournament selection. Evol. Comput. 2000, 1, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Helmuth, T.; Spector, L.; Matheson, J. Solving Uncompromising Problems with Lexicase Selection. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2015, 19, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz Echeandía, M.; de la Puente, A.O.; Alfonseca, M. Attribute grammar evolution. In Proceedings of the International Work-Conference on the Interplay Between Natural and Artificial Computation, Las Palmas, Spain, 15–18 June 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 182–191. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, M.R.; Ryan, C. On improving grammatical evolution performance in symbolic regression with attribute grammar. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2014 Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–16 July 2014; pp. 139–140. [Google Scholar]

- Girardi, A.; De-Oliveira, T.; Ghissoni, S.; Aguirre, P.C.; Compassi-Severo, L. A comprehensive review on automation-based sizing techniques for analog IC design. J. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2022, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebulum, R.; Pacheco, M.; Vellasco, M. Comparison of different evolutionary methodologies applied to electronic filter design. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation Proceedings. IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence (Cat. No.98TH8360), Anchorage, Alaska, 4–9 May 1998; pp. 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koza, J.R. Genetic Programming III: Darwinian Invention and Problem Solving; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; Duarte-Villaseáor, M.A. Evolutionary electronics: Automatic synthesis of analog circuits by GAs. In Success in Evolutionary Computation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, G.R.; Reyes-Garcia, C.A. Applications of evolutionary algorithms in the design automation of analog integrated circuits. J. Appl. Sci. 2010, 10, 1859–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Cho, S.B. Automated synthesis of multiple analog circuits using evolutionary computation for redundancy-based fault-tolerance. Appl. Soft Comput. 2012, 12, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlenbein, H.; Zinchenko, L.; Kureichik, V.; Mahnig, T. Effective mutation rate for probabilistic evolutionary design of analogue electrical circuits. Appl. Soft Comput. 2007, 7, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Higuchi, T. Promises and challenges of evolvable hardware. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Part C (Appl. Rev.) 1999, 29, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConaghy, T.; Gielen, G. Genetic programming in industrial analog CAD: Applications and challenges. In Genetic Programming Theory and Practice III; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, M.; Brabazon, A. Recent patents on genetic programming. Recent Patents Comput. Sci. 2009, 2, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- McConaghy, T.; Palmers, P.; Steyaert, M.; Gielen, G.G. Variation-aware structural synthesis of analog circuits via hierarchical building blocks and structural homotopy. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2009, 28, 1281–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConaghy, T.; Eeckelaert, T.; Gielen, G. CAFFEINE: Template-free symbolic model generation of analog circuits via canonical form functions and genetic programming. In Proceedings of the Design, Automation and Test in Europe, Munich, Germany, 7–11 March 2005; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 1082–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Kunaver, M. Grammatical evolution-based analog circuit synthesis. Inf. MIDEM 2019, 49, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Castejón, F.; Carmona, E.J. Automatic design of analog electronic circuits using grammatical evolution. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 62, 1003–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žaloudek, L.; Sekanina, L. Transistor-level evolution of digital circuits using a special circuit simulator. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Evolvable Systems, Prague, Czech Republic, 21–24 September 2008; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 320–331. [Google Scholar]

- Campilho-Gomes, M.; Tavares, R.; Goes, J. Automatic flat-level circuit generation with genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the Doctoral Conference on Computing, Electrical and Industrial Systems, Costa de Caparica, Portugal, 1–3 July 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, F.H., III; Koza, J.R.; Keane, M.A.; Yu, J.; Mydlowec, W.; Stiffelman, O. Evolution by Means of Genetic Programming of Analog Circuits that Perform Digital Functions. In Proceedings of the GECCO, Orlando, FL, USA, 13–17 July 1999; pp. 1477–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Settaluri, K.; Haj-Ali, A.; Huang, Q.; Hakhamaneshi, K.; Nikolic, B. Autockt: Deep reinforcement learning of analog circuit designs. In Proceedings of the 2020 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Grenoble, France, 9–13 March 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, K.; Yang, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, N.; Lee, H.S.; Han, S. GCN-RL circuit designer: Transferable transistor sizing with graph neural networks and reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 July 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Petrus, E.S. SKILL: A Lisp based extension language. ACM SIGPLAN Lisp Pointers 1993, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloatti, L.; Wade, M.; Stojanovic, V.; Popovic, M.; Ram, R.J. Photonics design tool for advanced CMOS nodes. IET Optoelectron. 2015, 9, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.; Carvalho, S.; Dias, D.M.; Naredo, E.; Sullivan, J.P.; Ryan, C. GRAPE: Grammatical Algorithms in Python for Evolution. Signals 2022, 3, 642–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koza, J.R.; Bennett, F.H., III; Andre, D.; Keane, M.A. Automated design of both the topology and sizing of analog electrical circuits using genetic programming. In Artificial Intelligence in Design’96; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Noren, K.V.; Ross, J.E. Analog circuit design using genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the Second Online Symposium for Electronics Engineers, Denver, CO, USA, 7–9 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Karci, H.; Tohumoğlu, G.; Nacaroğlu, A. Speciation-based genetic algorithm in analog circuit design. Turk. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2016, 24, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malits, M.; Brouk, I.; Nemirovsky, Y. Study of CMOS-SOI Integrated Temperature Sensing Circuits for On-Chip Temperature Monitoring. Sensors 2018, 18, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Population Size | 800 |

| No. of Generations | 40 |

| No. of Run | 1 |

| Initialisation | Sensible |

| Mutation Rate | 0.01 |

| Crossover Rate | 0.8 |

| Elitism | Yes |

| Algorithm | NSGA-II |

| Metric | CMOS | TGL | GDI | Evolved (90–10%) | Evolved (70–30%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Transistors | 4 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Average Power (W) | 12.66 n | 29.99 n | 14.05 n | 9.201 n | 8.99 n |

| Delay (s) | 121.6 p | 127.4 p | 92.32 p | 123.6 p | 91.39 p |

| PDP (J) | 1.539 a | 3.821 a | 1.297 a | 1.137 a | 0.822 a |

| Metric | CMOS | TGL | GDI | Evolved (90–10%) | Evolved (70–30%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Transistors | 4 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Average Power (W) | 6.934 n | 24.24 n | 9.862 n | 5.834 n | 5.834 n |

| Delay (s) | 154.7 p | 117.9 p | 83.18 p | 137.9 p | 137.9 p |

| PDP (J) | 1.073 a | 2.858 a | 0.82 a | 0.805 a | 0.805 a |

| Metric | PTAT (Gold) Circuit | Evolved Best-Fit Individual |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (V/°C) | 1.18 m | 1.30 m |

| INL (V) | 6.94 m | 2.408 m |

| Nominal Temp. Static Power (W) | 15.6 µ | 4.524 µ |

| Area (m2) | 184 p | 199.8 f |

| No. of Transistors | 5 | 2 |

| No. of Resistors | 2 | 0 |

| Domain | EA(s) | Application/Target | Key Contribution | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing methods available in the literature | ||||

| Analogue circuits | GP | Analogue building blocks such as filters, amplifiers (SPICE-based) | Demonstrated complete analogue circuit evolution [25,26]. Widely adopted approach with flexible topology search [32,33,34,35]. | Tree-based GP leads to bloat; manual seeding/topology intervention; front-end only, no end-to-end automation. |

| Analogue circuits | GA, UMDA | Current mirrors, differential pairs | Device sizing and optimisation without analytical models [27,28,29,30]. | Limited structural exploration; high design complexity; front-end only, no end-to-end automation. |

| Analogue circuits | GE | Small transistor-level blocks | Grammar-driven synthesis ensures syntactic validity [36,37]. | Limited semantic control; small scale; front-end only, no end-to-end automation. |

| Digital circuits | GE | Logic gates, arithmetic circuits (SPICE evaluation) | Block grammars enable diverse and valid designs [38]. | Mostly component-level; not full systems; front-end only, no end-to-end automation. |

| Digital circuits | GA, GP | Transistor-level digital designs | Optimisation of correctness, delay, and power [39,40]. | Limited automation; high design complexity; front-end only, no end-to-end automation. |

| Digital circuits | GE (HDL-based) | Verilog/VHDL code generation | Generates syntactically valid HDL for synthesis [16,17,18]. | Focused on gate/behavioural level; front-end only, no end-to-end automation. |

| EH | – | Digital logic, FPGAs, fault-tolerant systems | Low-level synthesis and adaptation; hardware-in-the-loop testing [31]. | High evaluation cost; domain-specific; front-end only, no end-to-end automation. |

| RL | – | Circuit optimisation (early studies) | Complementary to EAs; learning-guided optimisation [41,42]. | Still nascent at the transistor level. |

| Proposed method | ||||

| Analogue and Digital circuits | GE | Transistor (device) level circuit design using Cadence SKILL | Front-end, end-to-end automation; topology and device sizing automation; can be extended to back-end automation as well. | Not yet tested on complex analogue or digital circuits. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarma, R.; Singh, D.K.; Sediek, M.K.N.; Ryan, C. Machine Learning Framework for Automated Transistor-Level Analogue and Digital Circuit Synthesis. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2169. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122169

Sarma R, Singh DK, Sediek MKN, Ryan C. Machine Learning Framework for Automated Transistor-Level Analogue and Digital Circuit Synthesis. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2169. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122169

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarma, Rajkumar, Dhiraj Kumar Singh, Moataz Kadry Nasser Sediek, and Conor Ryan. 2025. "Machine Learning Framework for Automated Transistor-Level Analogue and Digital Circuit Synthesis" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2169. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122169

APA StyleSarma, R., Singh, D. K., Sediek, M. K. N., & Ryan, C. (2025). Machine Learning Framework for Automated Transistor-Level Analogue and Digital Circuit Synthesis. Symmetry, 17(12), 2169. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122169