Platform-Targeted Technology Investment and Sales Mode Selection Considering Asymmetry of Power Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does targeted advertising affect the pricing of goods, advertising strategies, and commodity demand, and further affect the profit distribution of all parties?

- Under different power structures, how should platforms and manufacturers choose the sales mode?

- Under what conditions should the platform make targeted technology investments to optimize its operational efficiency and market performance?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Targeted Advertising

2.2. Platform Sales Mode

2.3. Summary and Research Gap

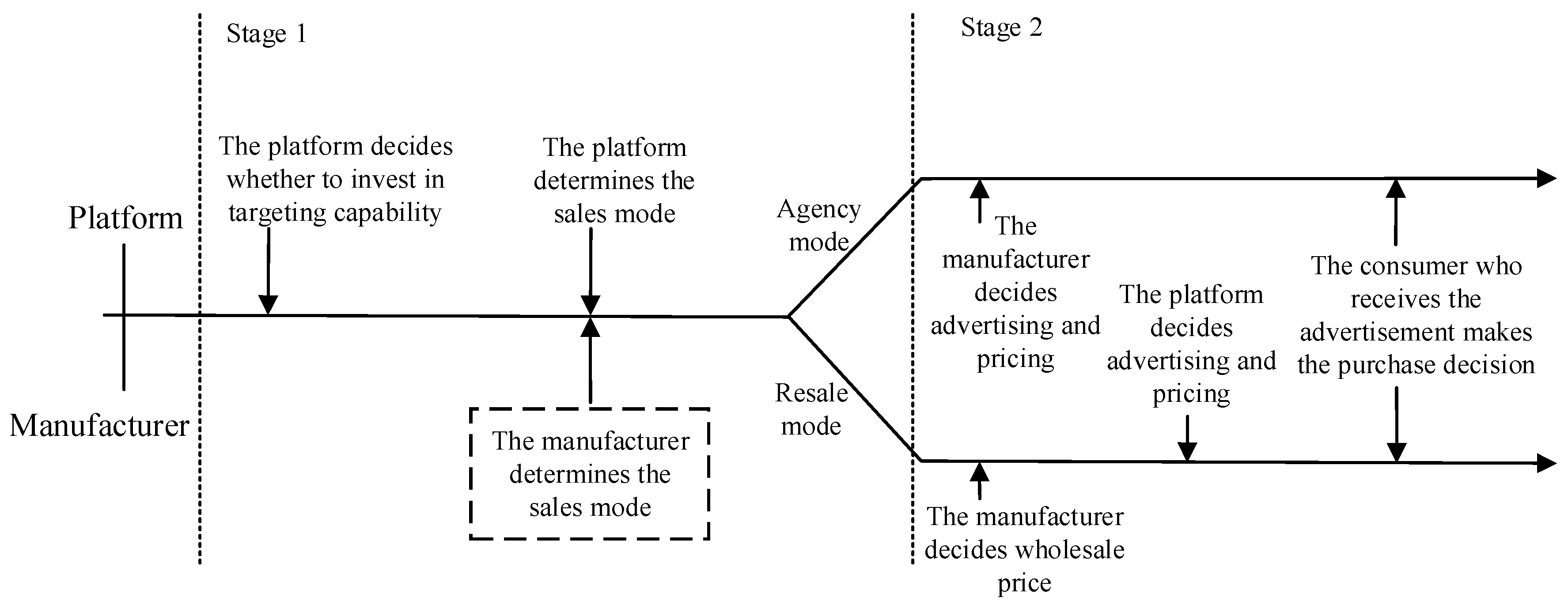

3. Model

3.1. Agency Mode + Uniform Advertising (AU)

3.2. Agency Mode + Targeted Advertising (AT)

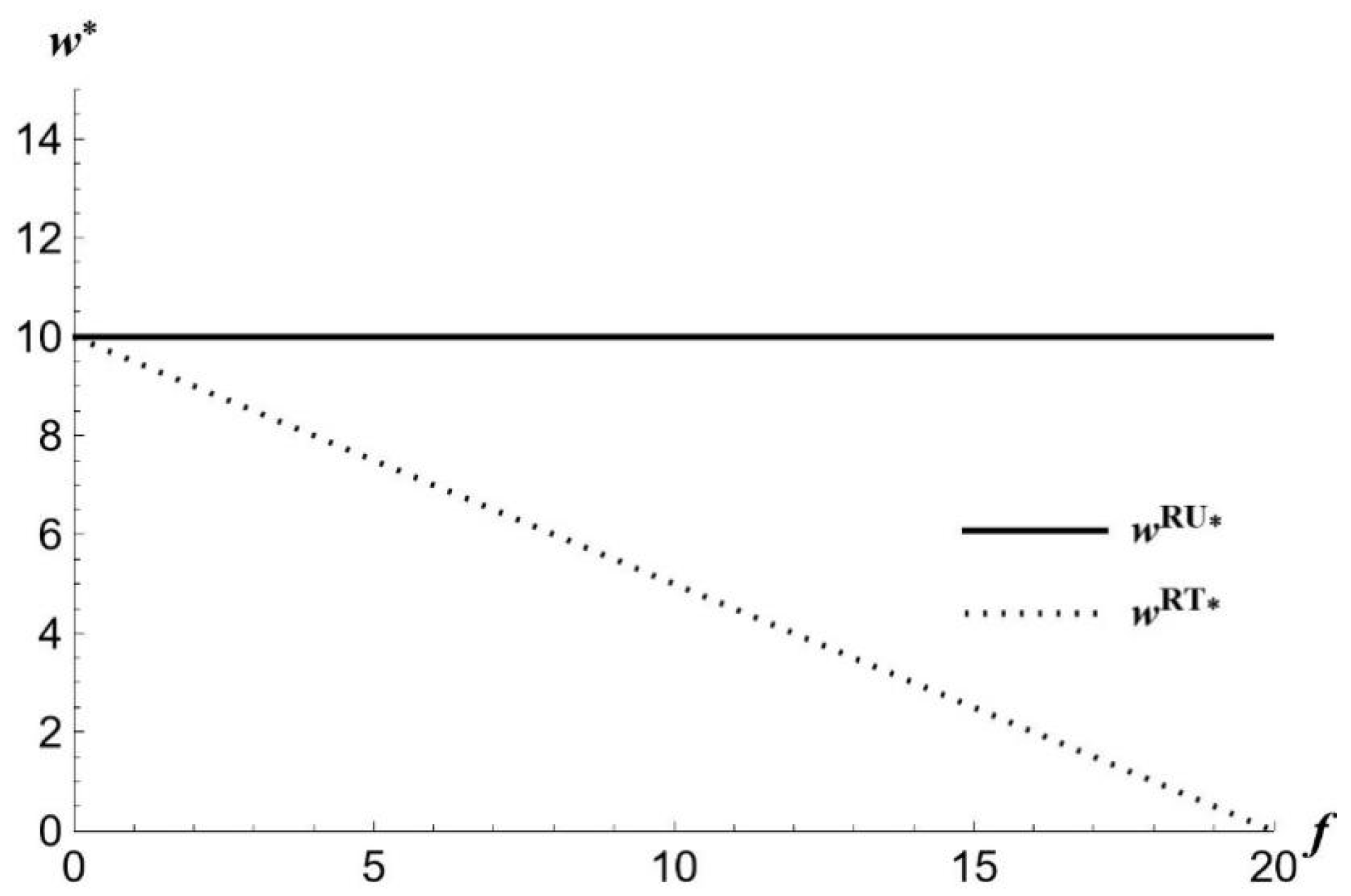

3.3. Resale Mode + Uniform Advertising (RU)

3.4. Resale Mode + Targeted Advertising (RT)

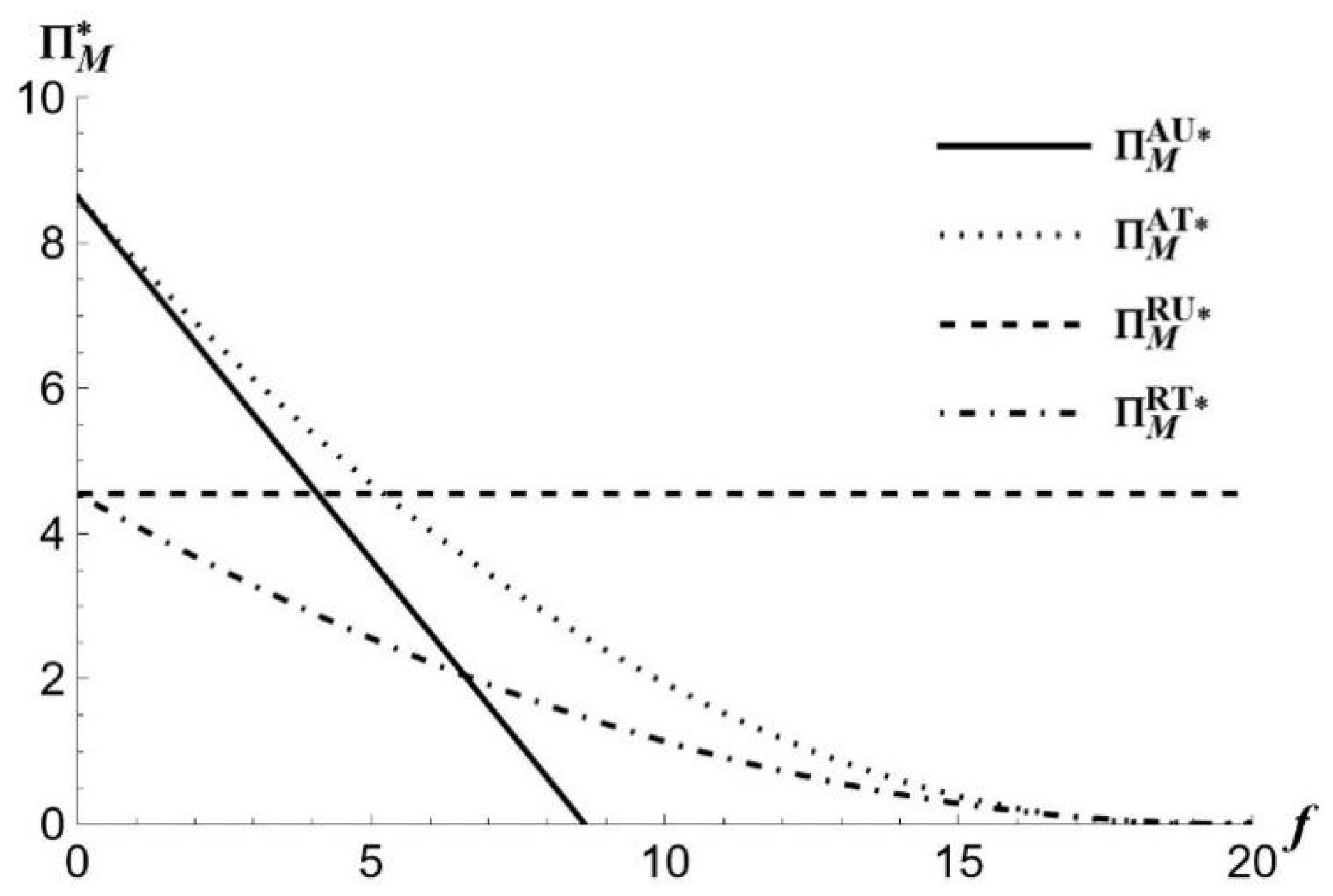

4. Equilibrium Analysis

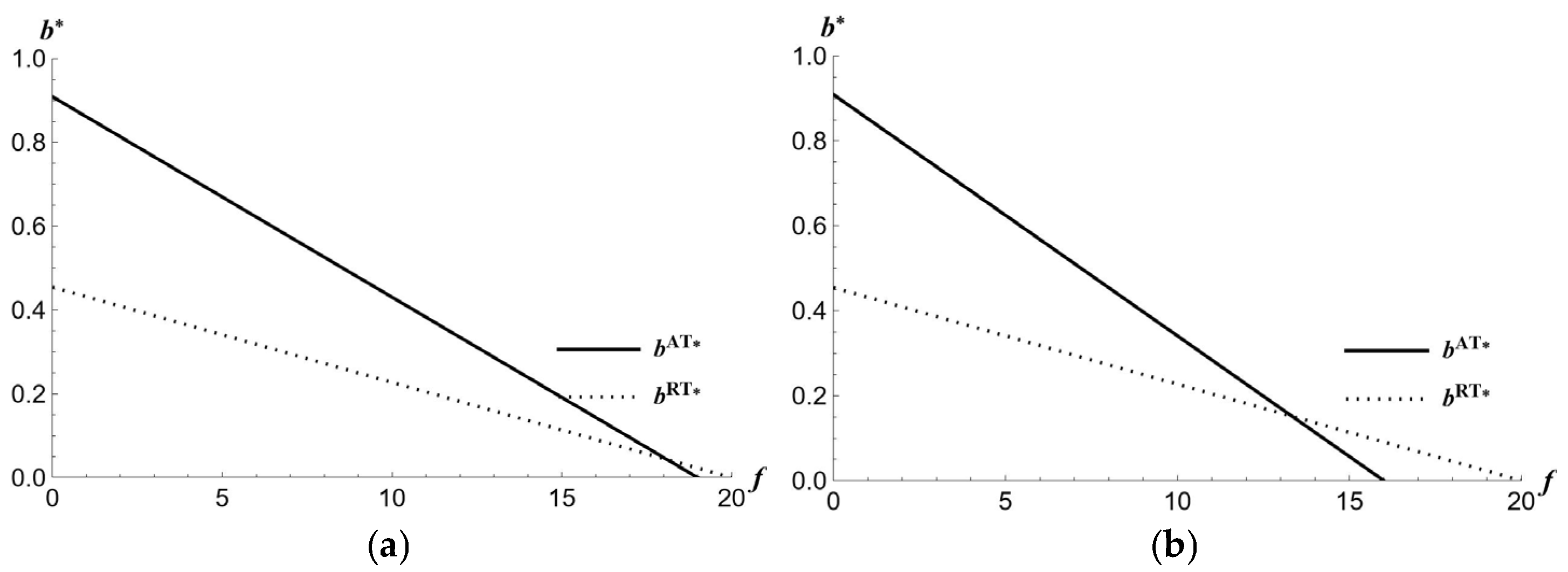

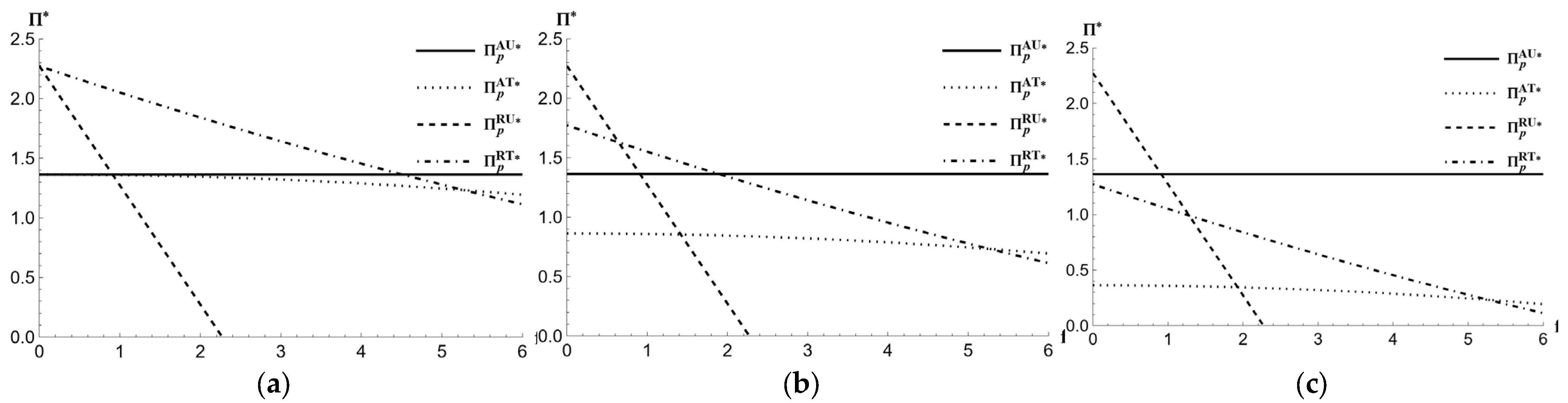

4.1. The Effect of Targeted Advertising on Equilibrium

- 1.

- , ;

- 2.

- , ;

- 3.

- .

4.2. Sales Mode Selection

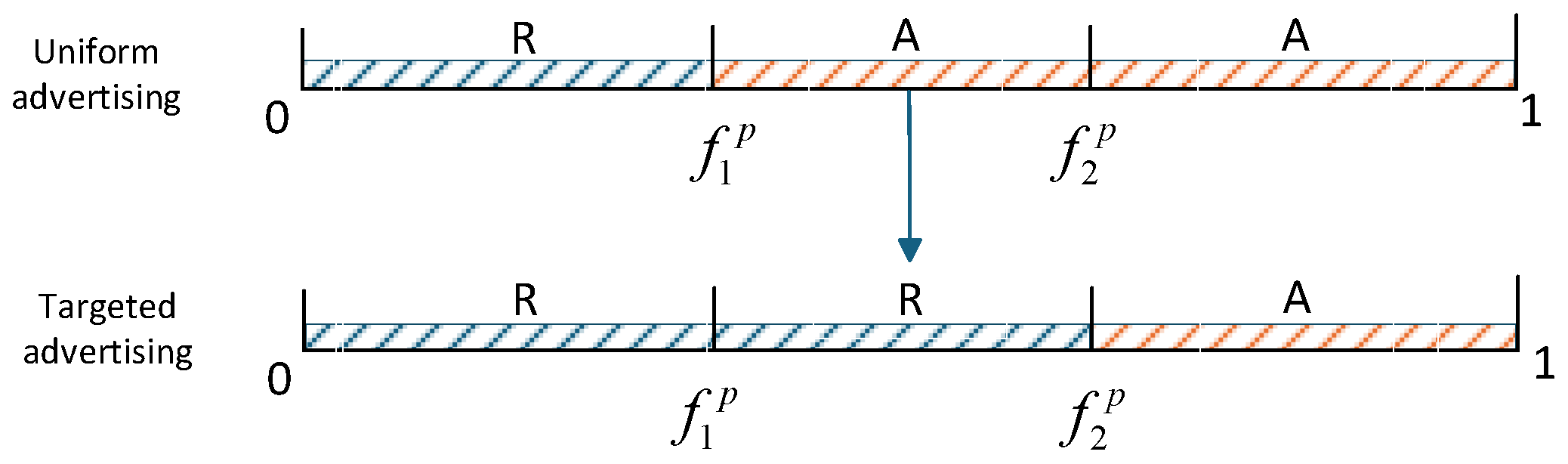

4.2.1. Platform-Led Sales Mode

- 1.

- First item: under uniform advertising, when , the platform chooses the resale mode; when , the platform chooses the agency mode.

- 2.

- Under targeted advertising, when , the platform chooses the resale mode; when , the platform chooses the agency mode.

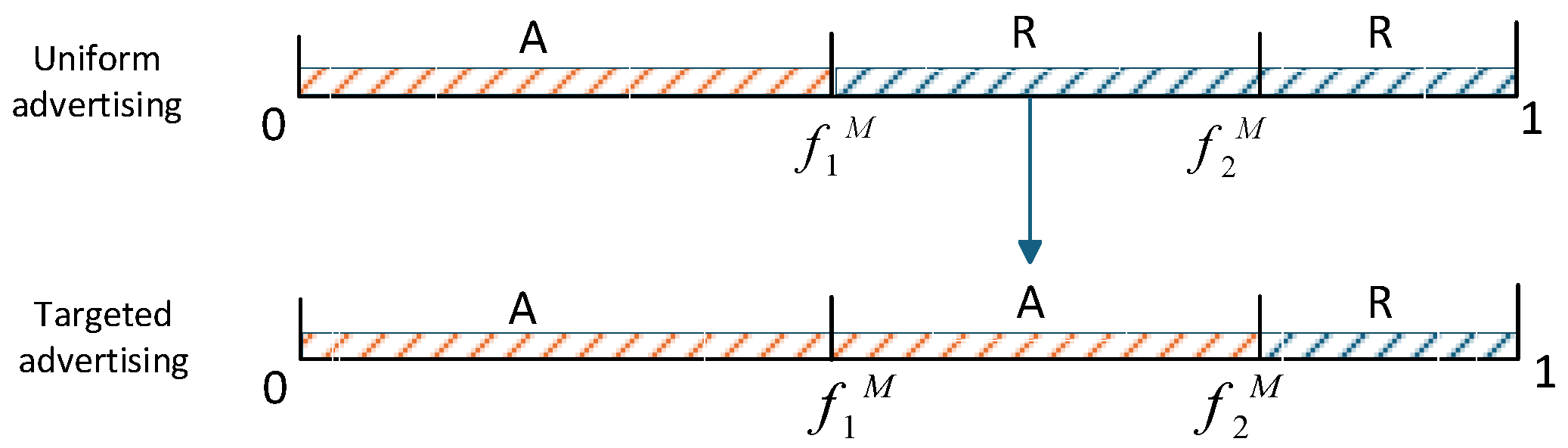

4.2.2. Manufacturer-Led the Sales Mode

- 1.

- Under uniform advertising, if , the manufacturer chooses the agency mode, otherwise they choose the resale mode.

- 2.

- Under targeted advertising, if , the manufacturer chooses the agency mode, otherwise they choose the resale mode.

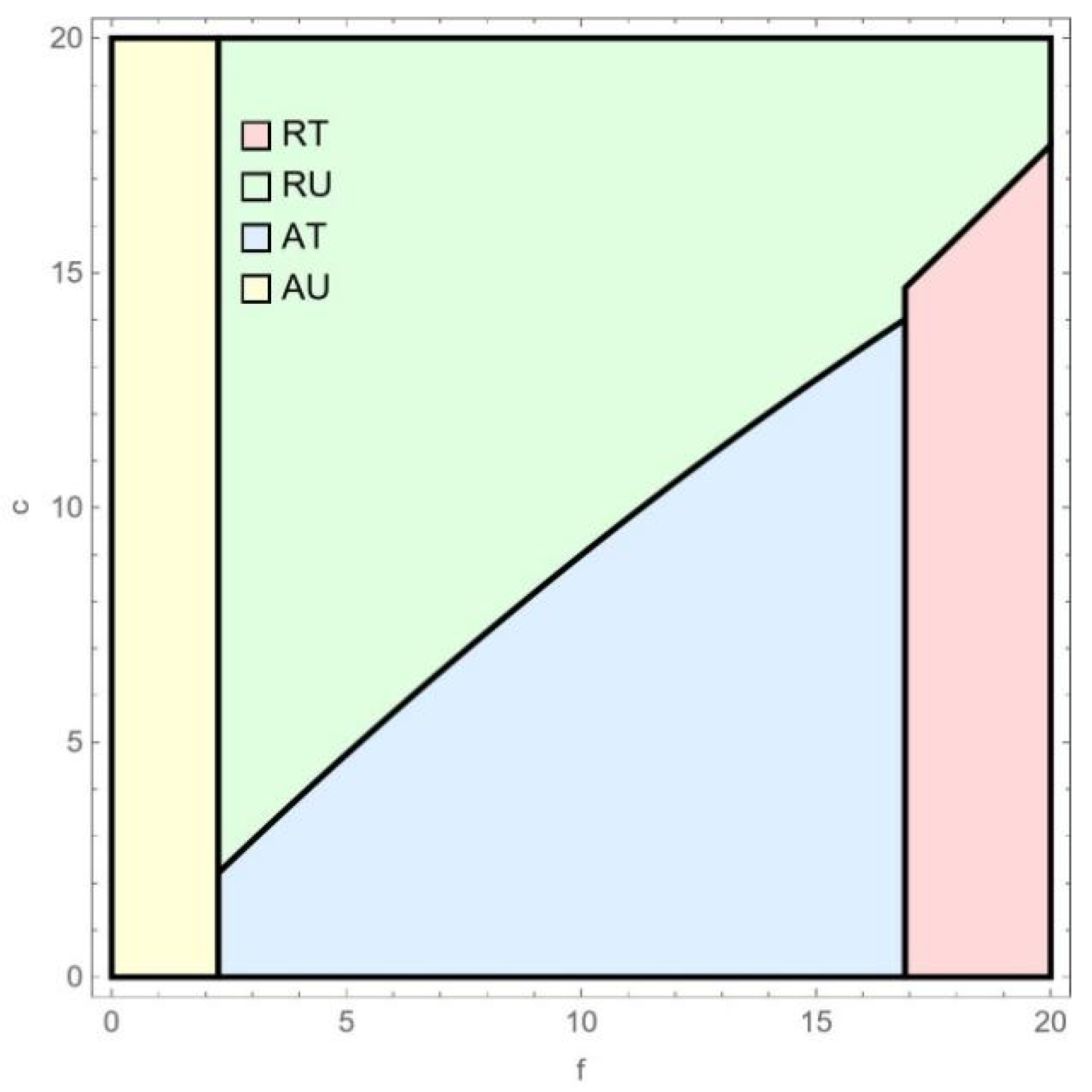

4.3. Targeted Investment Decisions

4.3.1. Platform-Led Sales Mode

- 1.

- When , the platform invests in targeted technology and chooses the resale mode (RT);

- 2.

- When and , the platform does not invest and chooses the resale mode (RU);

- 3.

- When and , the platform does not invest and chooses the agency mode (AU);

- 4.

- When , the platform does not invest. If , the platform chooses the resale mode (AU). If , the platform chooses the agency mode (RU).

4.3.2. Manufacturer-Led the Sales Mode

- 1.

- When , the platform chooses not to invest in targeted technology, and the manufacturer chooses the agency mode (AU);

- 2.

- When , if , the platform invests in targeted technology and the manufacturer chooses the agency mode (AT); if , the platform does not invest in targeted technology and the manufacturer chooses the resale mode (RU);

- 3.

- When , if , the platform invests in targeted technology and the manufacturer chooses the resale mode (RT). If , the platform does not invest in targeted technology and the manufacturer chooses the resale mode (RU).

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Management Implications

5.3. Limitations

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AU | The scenario “agency mode + uniform advertising” |

| AT | The scenario “agency mode + targeted advertising” |

| RU | The scenario “resale mode + uniform advertising” |

| RT | The scenario “resale mode + targeted advertising” |

References

- Iyer, G.; Soberman, D.; Villas-Boas, J.M. The targeting of advertising. Mark. Sci. 2005, 24, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, X. Targeted advertising by asymmetric firms. Omega 2019, 89, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despotakis, S.; Yu, J. Multidimensional targeting and consumer response. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 4518–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, H.; Yu, J. Competitive targeted online advertising. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2023, 87, 102924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Balachander, S. Coordinating traditional media advertising and online advertising in brand marketing. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023, 32, 1865–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Shin, J.; Yu, J. Targeted advertising as implicit recommendation: Strategic mistargeting and personal data opt-out. Mark. Sci. 2025, 44, 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, W. Attack and defend: The role of targeting in a distribution channel. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, S.; Shahrokhi Tehrani, S. Targeted advertising spending and price on hoteling line. Mark. Sci. 2023, 42, 1029–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, R.B.; Resende, J. Competitive targeted advertising with price discrimination. Mark. Sci. 2016, 35, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.J.; Chen, Y.J. Targeted information release in social networks. Oper. Res. 2016, 64, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhong, W.J.; Mei, S.E. Advertising strategies of competing firms considering consumer privacy concerns. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 2424–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Yang, L. Platform advertising and targeted promotion: Paid or free? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 55, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepall, L.; Richards, D. Targeted advertising, concentration, and consumer welfare. Inf. Econ. Policy 2025, 70, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Platform targeted capability investment, seller price and advertising strategies. INFOR Inf. Syst. Oper. Res. 2025, 63, 668–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, V.; Jerath, K.; Zhang, Z.J. Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 2259–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Vakharia, A.J.; Tan, Y.; Xu, Y. Marketplace, reseller, or hybrid: Strategic analysis of an emerging e-commerce model. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Agency selling or reselling: E-tailer information sharing with supplier offline entry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 280, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yan, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhao, R.N. Promotion decisions under asymmetric demand-generation information: Self-operated, online-platform and offline-outlet strategies. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 27, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Chen, J.; Li, W. Spillover effect of consumer awareness on third parties’ selling strategies and retailers’ platform openness. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 32, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Peng, J.; Li, J.; Xu, L. Impact of platform owner’s entry on third-party stores. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 1467–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.J.; Jerath, K.; Srinivasan, K. Firm strategies in the “mid tail” of platform-based retailing. Mark. Sci. 2011, 30, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Si, Y.; Han, Z.; Ma, C. Research on private label introduction and sales mode decision-making for e-commerce platforms considering coupon promotion strategies. Systems 2025, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Xiang, Z.; Ji, T. Platform’s premium store brand introduction and sales mode selection strategies with the cost-advantageous manufacturer. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiu, A.; Wright, J. Marketplace or reseller? Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.L.; Liu, Z.X.; Tian, L. The optimal combination between selling mode and logistics service strategy in an e-commerce market. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 289, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.Y.; Tong, S.L.; Wang, Y.J. Channel structures of online retail platforms. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2022, 24, 1547–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, J. Socially responsible e-commerce supply chains: Sales mode preference and store brand introduction. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 193, 103829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Yang, L. Resale or agency sale? Equilibrium analysis on the role of live streaming selling. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, N.; Fan, J.; Wu, X. The cost-sharing mechanism for blockchain technology adoption in the platform-led e-commerce supply Chain. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2025, 34, 156–179. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, F.; Li, B.; Lv, Y.; Qin, X. Eco-labels and sales mode selection strategies for e-commerce platform supply chain. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2024, 46, 1278–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirole, J. The Theory of Industrial Organization; MIT Press Books: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Literature | Platform | Sales Mode | Targeted Advertising | Power Structure | Targeted Technology Investment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iyer [1]; Zhang and He [2]; Despotakis and Yu [3]; Ning et al. [6]; Moorthy and Tehrani [8] | ✓ | ||||

| Hao and Yang [12] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Zhang [14] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Lu et al. [22] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Wan et al. [29] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Hagiu and Wright [24] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Zhang et al. [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| This paper | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Notations | Definitions |

|---|---|

| The utility of goods purchased by consumers located in x | |

| The consumer preference | |

| The unit mismatch cost | |

| Platform commission rate | |

| Consumer valuation of goods | |

| Wholesale price | |

| The selling price of a commodity | |

| The fixed cost of investment targeted technology | |

| Unit advertising cost | |

| Advertising volume | |

| Commodity demand | |

| Manufacturer’s profit | |

| Platform’s profit | |

| AU | Scenario “agency mode + uniform advertising” |

| AT | Scenario “agency mode + targeted advertising” |

| RU | Scenario “resale mode + uniform advertising” |

| RT | Scenario “resale mode + targeted advertising” |

| AU | AT | RU | RT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | |||

| — | — | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H. Platform-Targeted Technology Investment and Sales Mode Selection Considering Asymmetry of Power Structures. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2168. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122168

Zhang H. Platform-Targeted Technology Investment and Sales Mode Selection Considering Asymmetry of Power Structures. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2168. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122168

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hua. 2025. "Platform-Targeted Technology Investment and Sales Mode Selection Considering Asymmetry of Power Structures" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2168. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122168

APA StyleZhang, H. (2025). Platform-Targeted Technology Investment and Sales Mode Selection Considering Asymmetry of Power Structures. Symmetry, 17(12), 2168. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122168