Numerical Study of Symmetry in Tunneling-Induced Soil Arch

Abstract

1. Introduction

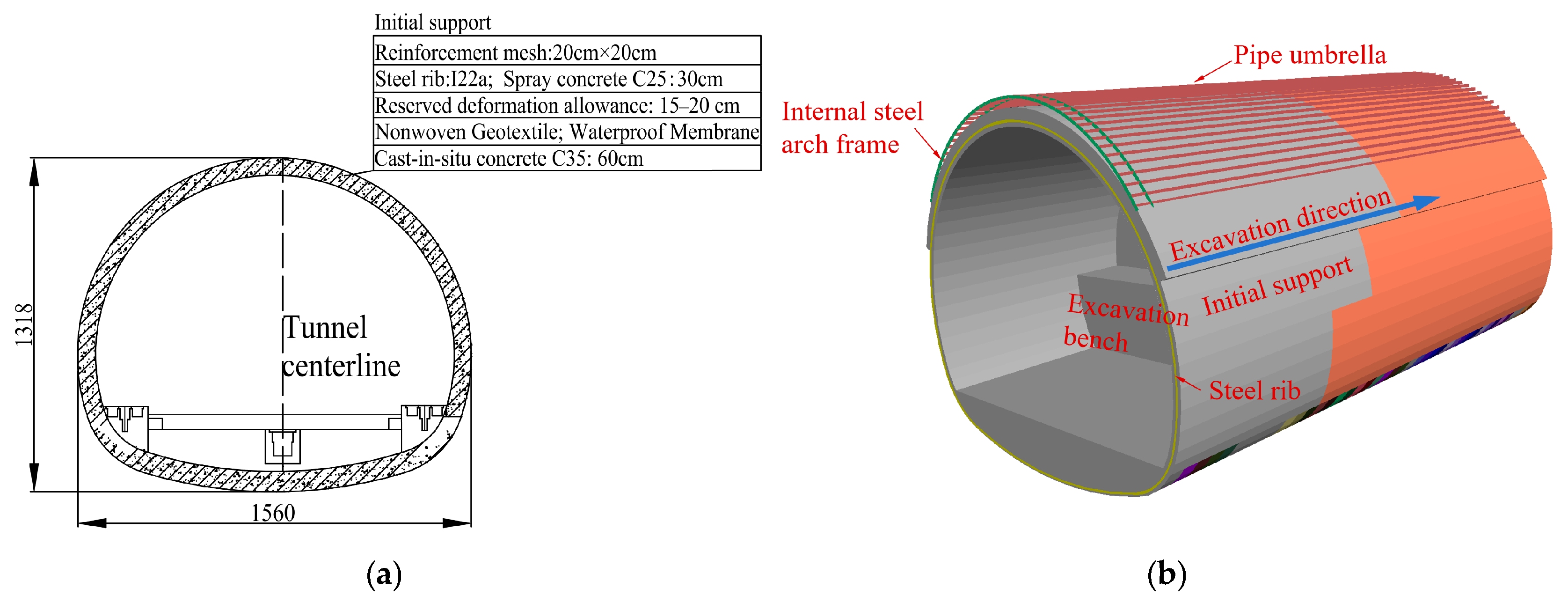

2. Engineering Background

3. Three-Dimensional Numerical Model

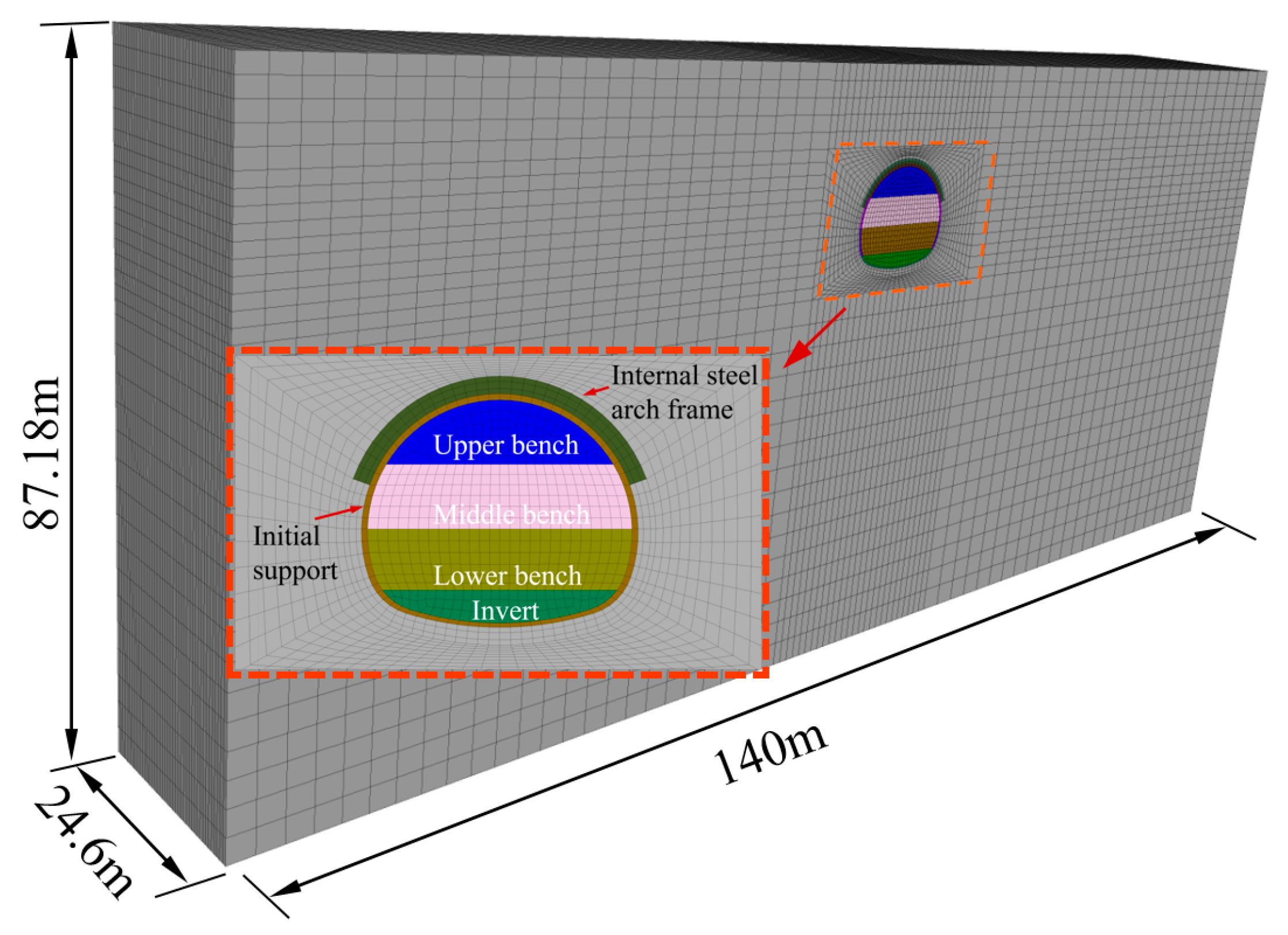

3.1. Model Establishment

3.2. Model Parameters

4. Results

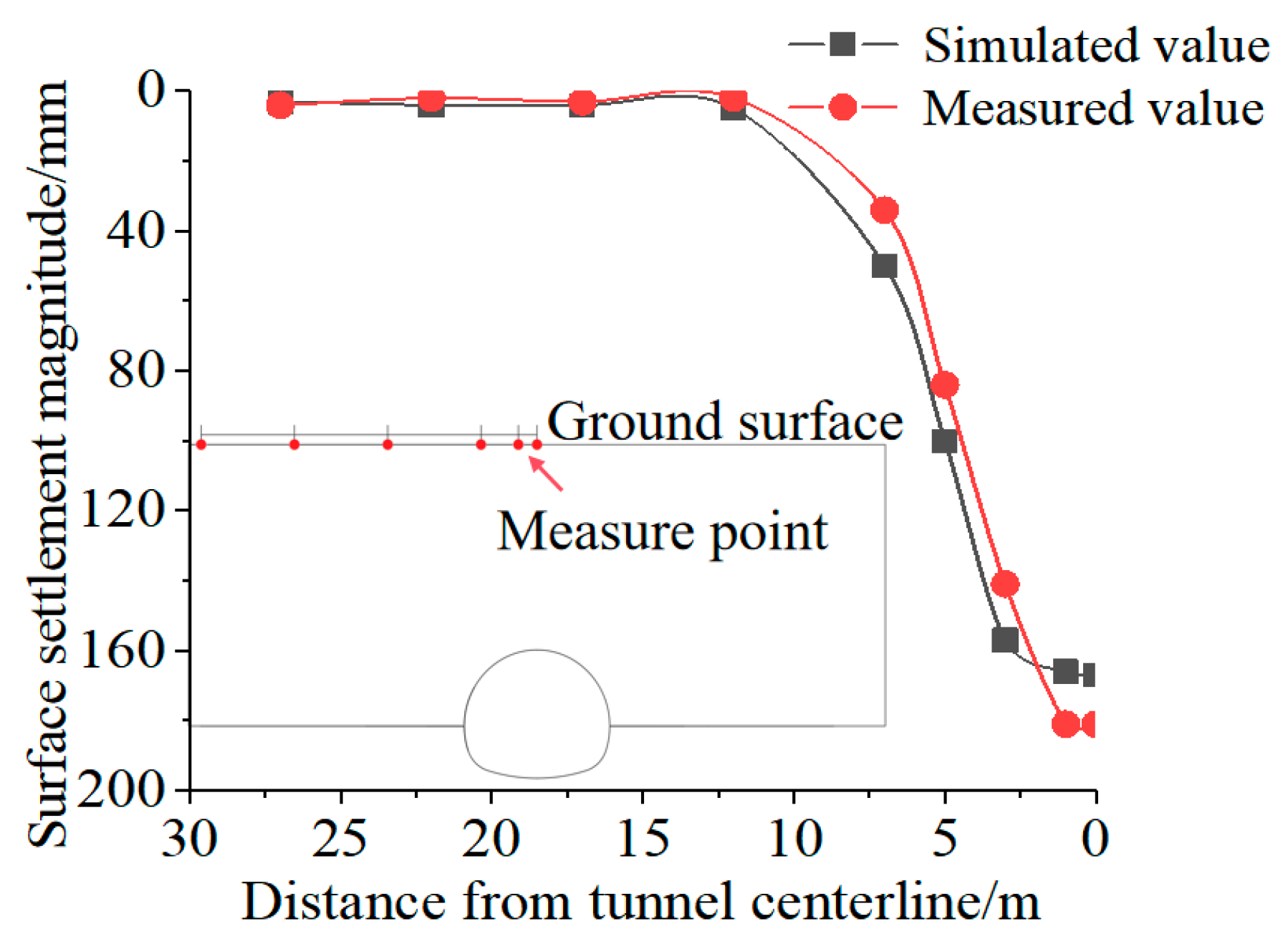

4.1. Validation of Simulation Model

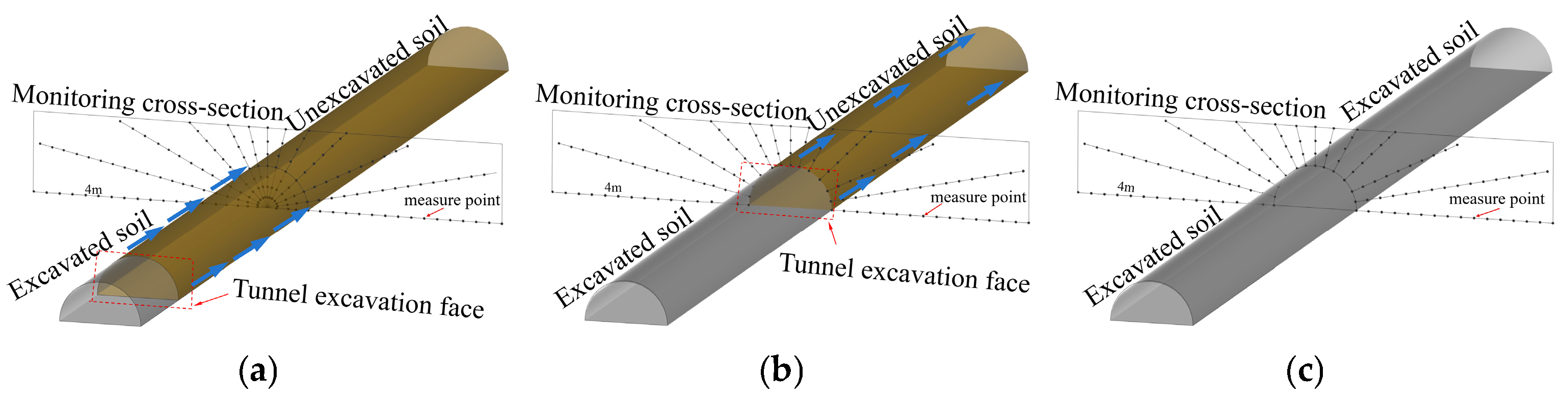

4.2. Monitoring Points Arrangement

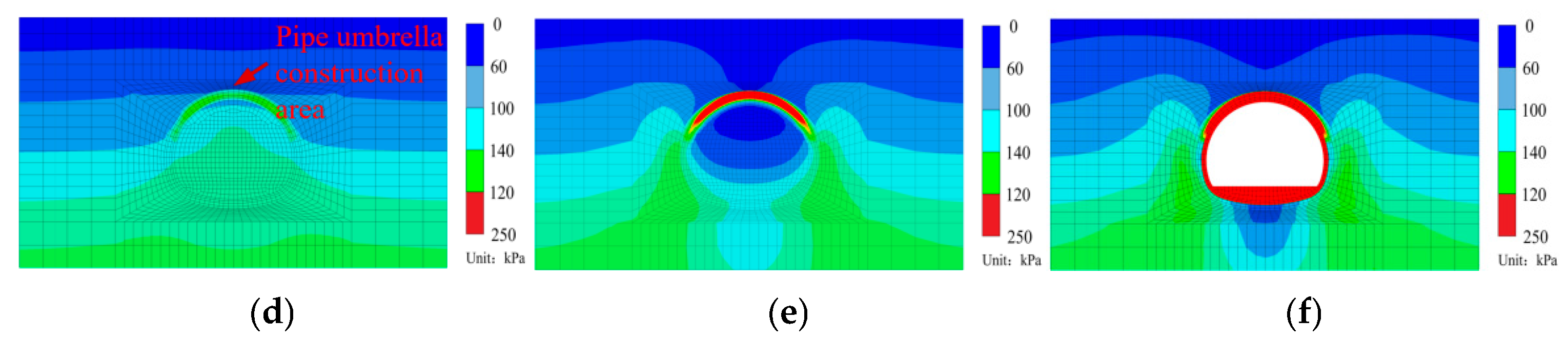

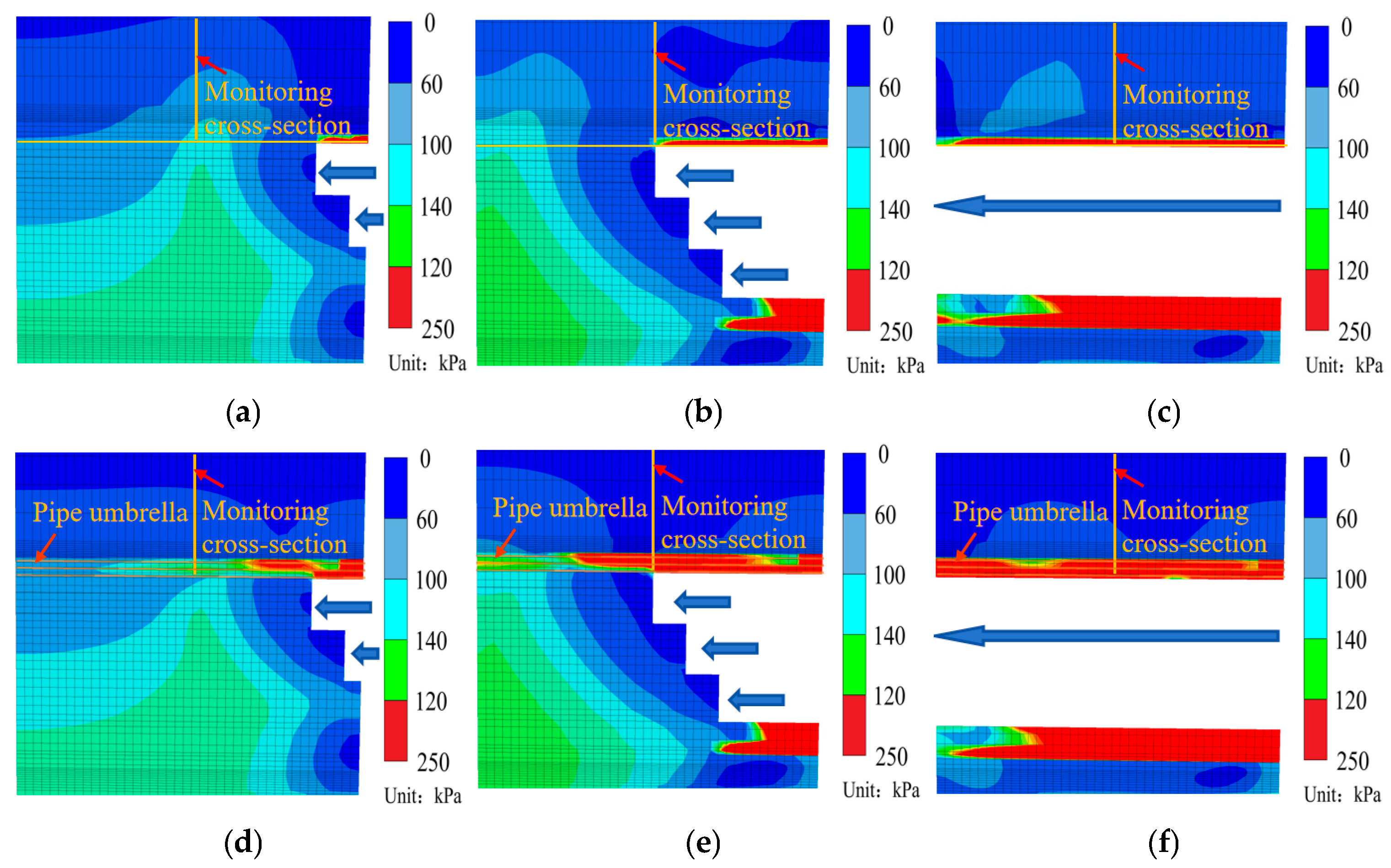

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Stress Field Evolution Under Two Working Conditions

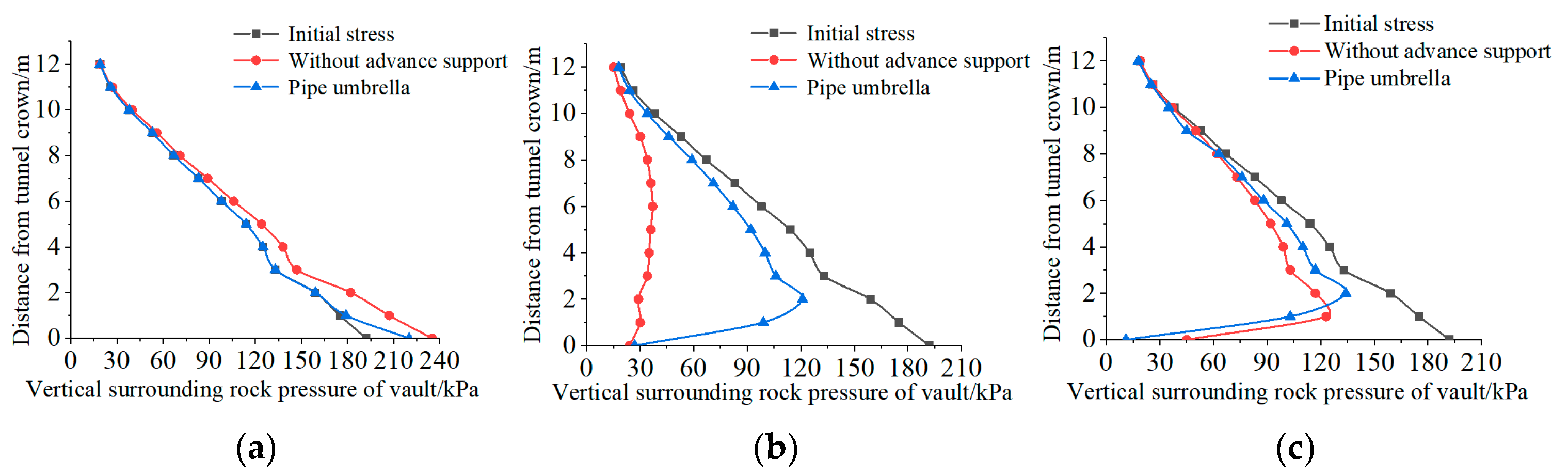

4.3.1. Vertical Stress Distribution at Different Depths Above the Vault

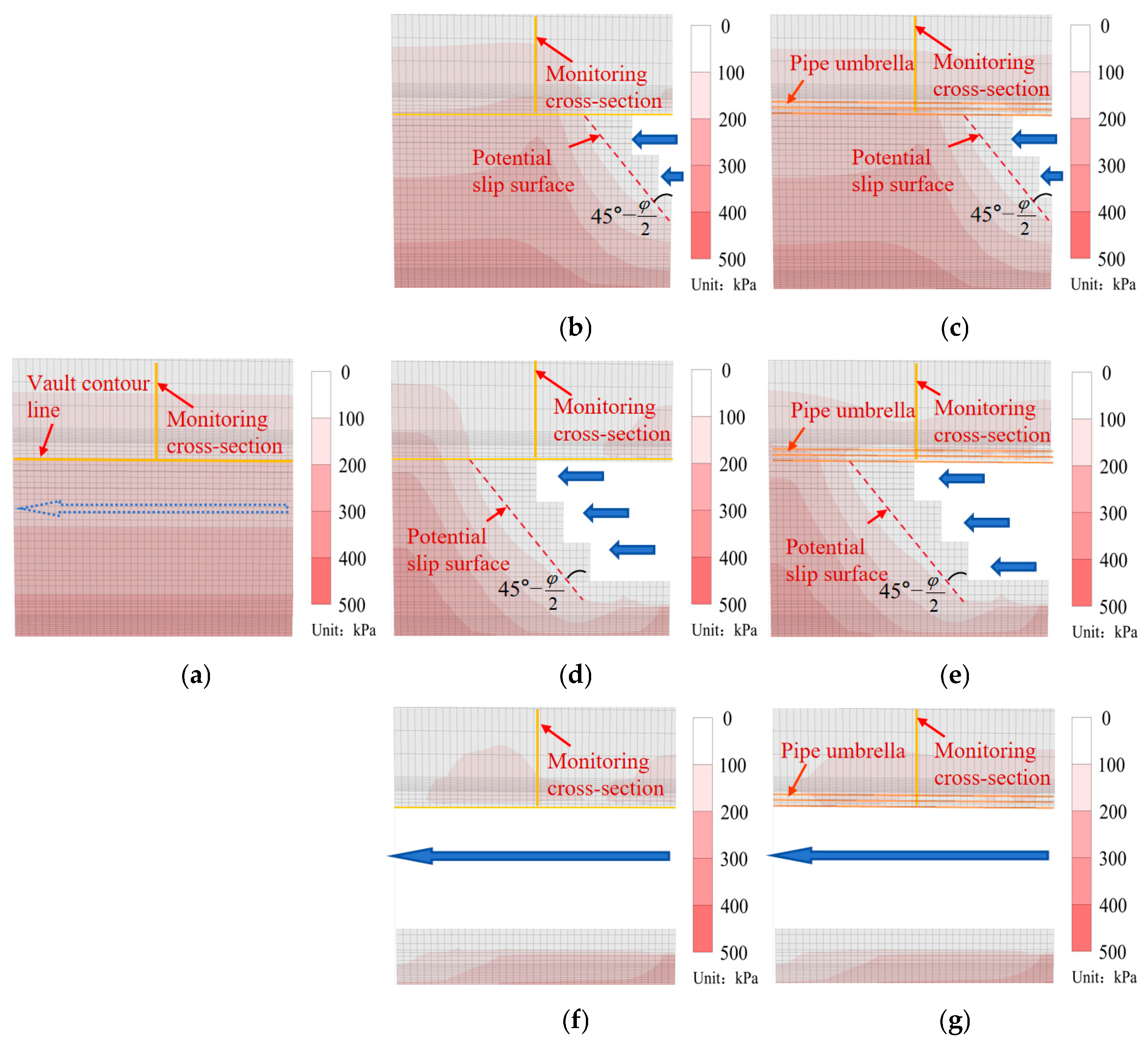

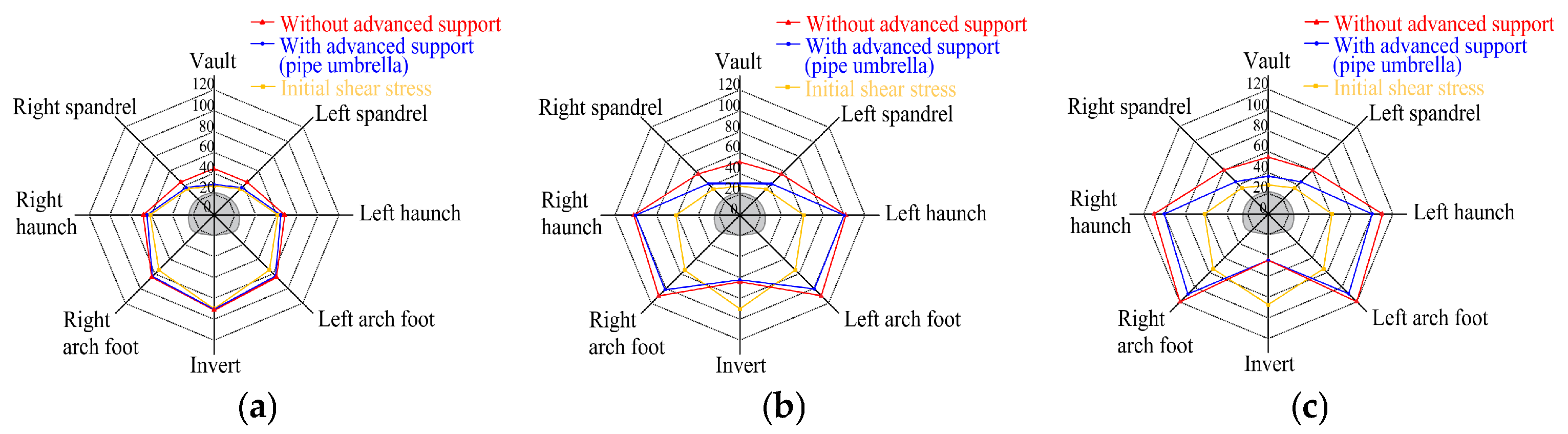

4.3.2. Maximum Shear Stress Distribution

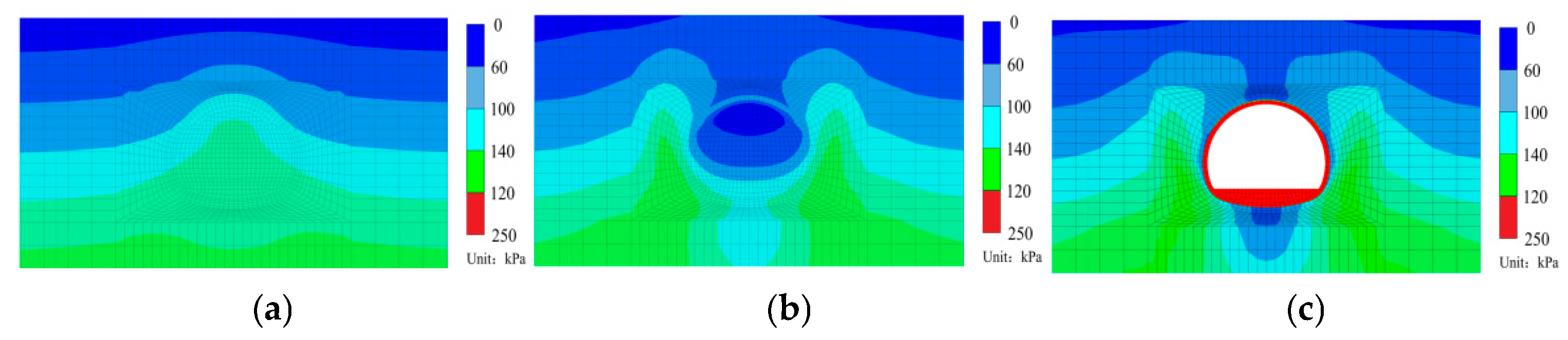

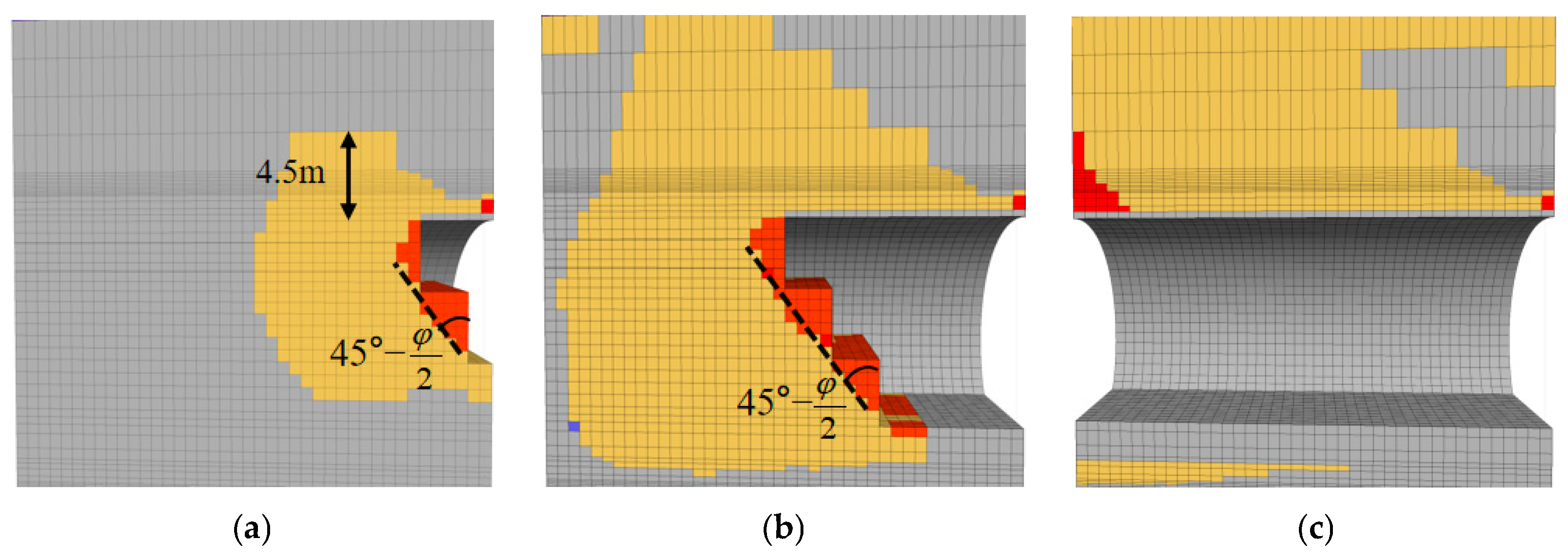

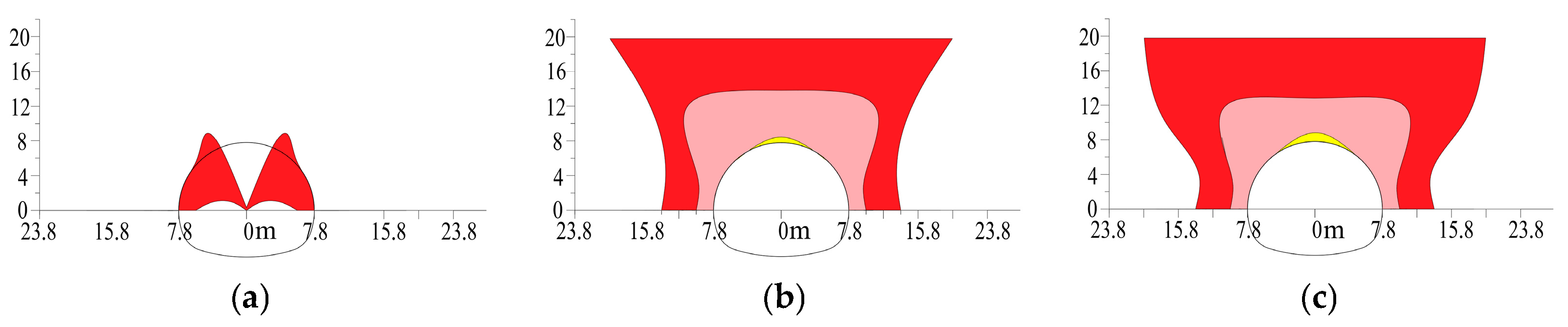

4.3.3. Plastic Zone

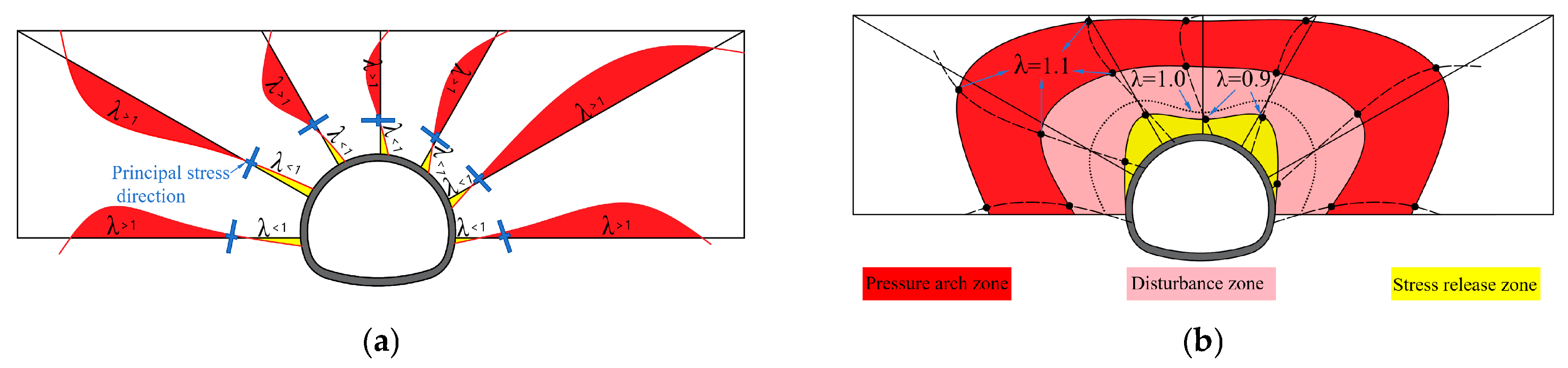

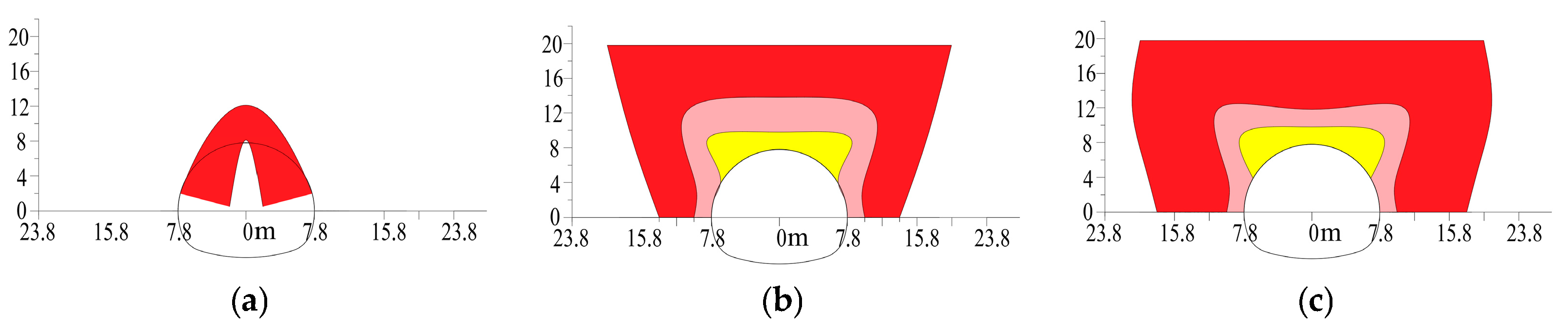

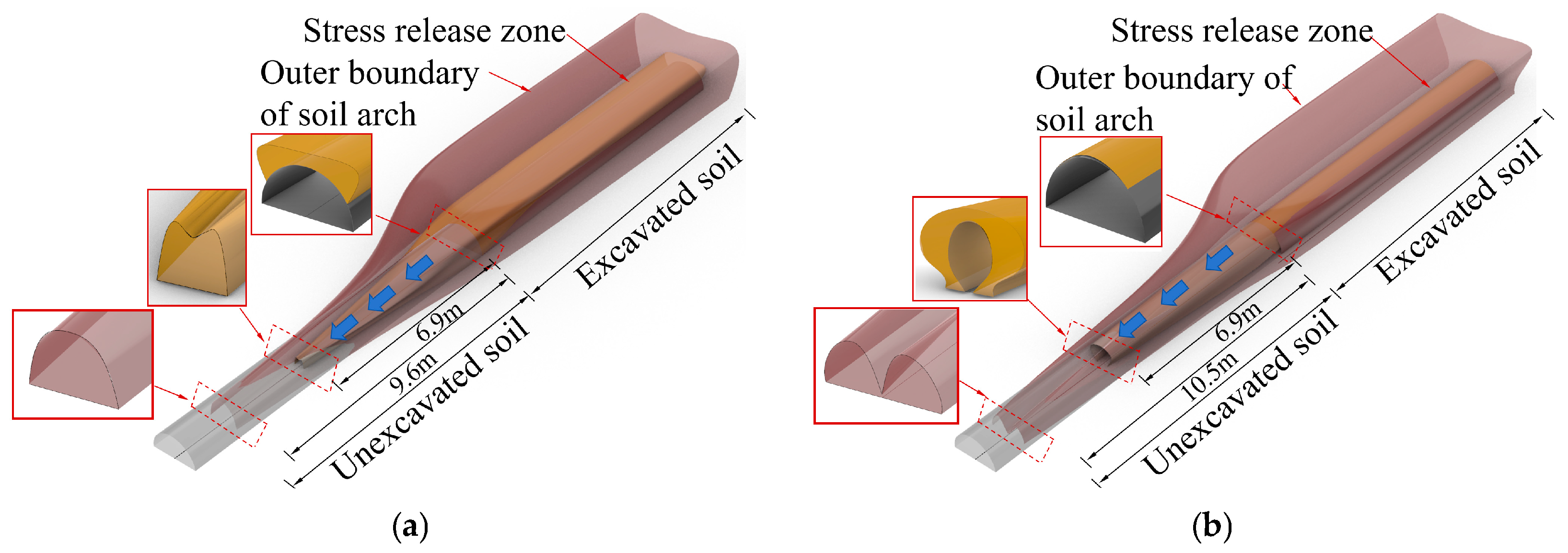

4.4. Evolution of Soil Arch

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The advanced pipe umbrella support system achieves effective full-process control over stress redistribution in the surrounding soil through its “pre-support and load-bearing” mechanism. This mechanism effectively alleviates stress concentration 0.5 D ahead of the tunnel excavation face, reduces the stress release magnitude at the vault from over 80% in unsupported conditions to below 30% when excavation reaches the monitoring section, and facilitates stable and orderly stress recovery following tunnel breakthrough. Ultimately, this results in the formation of a more efficient active pressure arch system with a higher load-bearing capacity.

- (2)

- The longitudinal beam-forming and transverse arch-forming effects of pipe umbrella significantly enhance the mechanical stability of surrounding soil. These effects effectively mitigate the concentration and propagation of shear stress at critical locations, such as the arch shoulder and arch foot. Furthermore, they reduce the extent of the plastic zone in the surrounding soil from 413.3 m2 (when fully penetrating to the ground surface without support) to 95.0 m2, achieving a reduction of over 77%. This reduction prevents overall instability of the surrounding soil and ensures construction safety.

- (3)

- The pipe umbrella support optimizes the formation mechanism and load-bearing efficiency of the soil arch. In unsupported conditions, the surrounding soil responds passively, leading to the development of a “passive soil arch” characterized by extensive coverage and considerable thickness, albeit with significant relaxation. In contrast, the pipe umbrella actively assumes and redistributes loads, prompting the surrounding soil to form an “active soil arch” with a greater influence depth and a markedly reduced relaxation zone, thus achieving efficient reconstruction of the load transfer path.

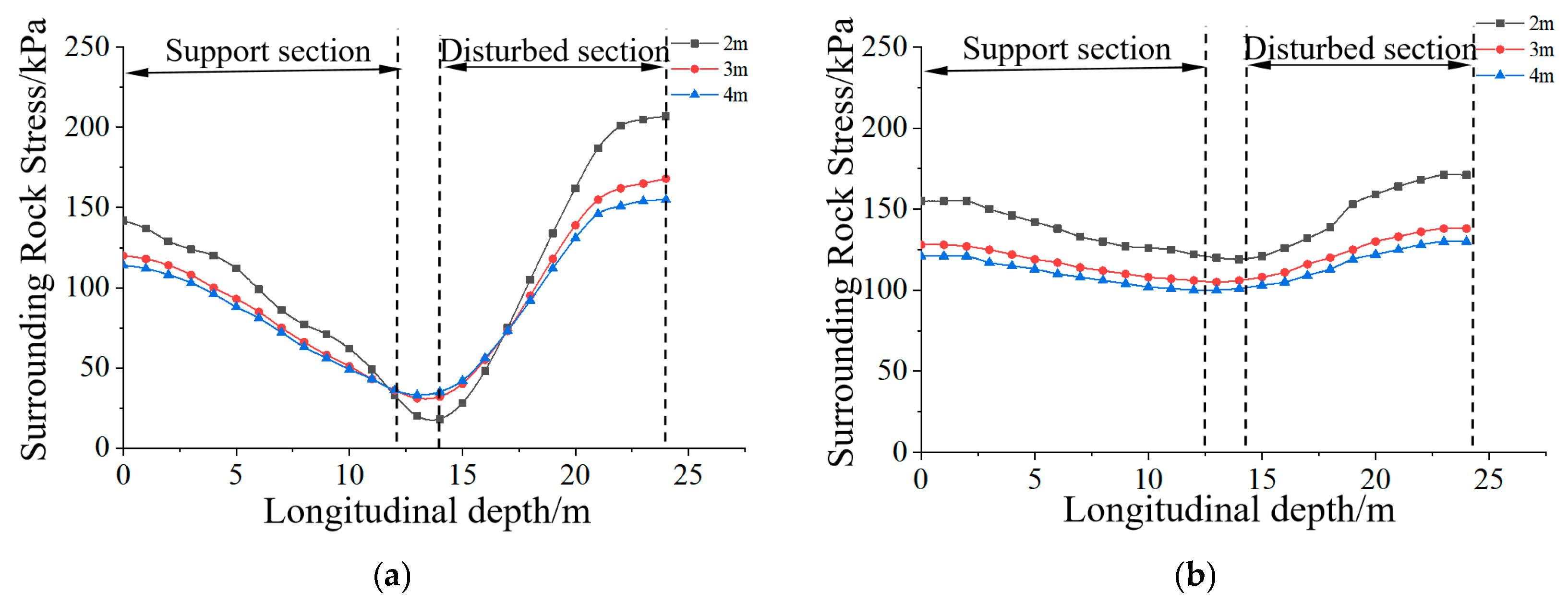

- (4)

- Based on the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of loads revealed by numerical simulation, the established Pasternak elastic foundation beam model, which accounts for the spatiotemporal effects of support, describes the segmented mechanical behavior of pipe umbrella in supported, unsupported, and disturbed zones. This model identifies the most unfavorable stress location of the pipe umbrella near the tunnel excavation face, theoretically elucidates its ‘longitudinal beam-forming’ mechanism from a mechanical perspective, and provides a quantitative theoretical tool for optimizing support parameters.

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.-Z.; Yan, S.-H.; Sun, W.-Y. Study on Destabilization and Damage Mechanism of surrounding soil in Shallow Buried Large Section Loess Tunnel. Railw. Eng. 2025, 65, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; He, W.-S. Study on the Application of Double-Side Heading Method in the Construction of Shallow and Large Section Loess Tunnel. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2022, 18, 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y.-C.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Miao, X.-Y. Analysis of Characteristics and Formation Mechanism of Ground Surface Cracks of Shallow Buried Loess Tunnel with Large Section. Railw. Stand. Des. 2020, 64, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.-G.; Wu, Z.-S.; Wang, W.-W.; Yang, L.; Feng, D. Large Deformation Control Technology and Effect of shallow Loess Tunnel with Large Section. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2020, 20, 2470–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.-H.; Bai, M.-L.; Ma, X.-M.; Xie, J.-T.; Mi, W.-J. Application Research on the Surface Grouting in Shallow Buried Loess Tunnel with Large Section. J. Railw. Eng. Soc. 2019, 36, 48–51+99. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.-W.; Han, X.-Q.; Liao, K. Real-Time Monitoring and Early Alarms for Collapse Prevention in a Shallow Loess Tunnel with a Large Section. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2014, 51, 11–15+22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-F.; Zhong, Z.-L. Research on the Large Deformation of Ultra-shallow and Large-bias Separated Tunnel in Loess Plateau and Its Treatment. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2012, 8, 1841–1845. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.-G.; Yang, G.-Q.; Cao, K.-L.; Wang, J.-H. Research on Bench Excavation Method for Large Section Sandy Loess Tunnel. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2025, 21, 600–609. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.-M.; Tan, Y.-M.; Yao, S.-Y.; Yan, Z.-J.; Zhang, J.-R.; Wang, S.-T. Deformation Control Mechanism of shallow Cohesive Loess Tunnel and Related Countermeasures. Tunn. Constr. 2023, 43, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.-Y.; Yu, X.-G.; Lin, D.-M.; Xu, C.-J. Comprehensive Deformation Control Technology for Shallow Buried Tunnel in Aeolian Sandy Loess. J. Eng. Geol. 2022, 30, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.-C.; Fan, F.-F.; Li, Z.-Q.; Li, B.-L.; Qiu, J.-L. Analysis of Control Effect of Large-section Loess Tunnel Crossing Gully Based on Large Tubular Shed Support. Highway 2020, 65, 380–385. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.-L.; Song, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Li, B. Double-layer Support Technology of Large-section Loess Tunnel by Benching Method. Strateg. Study CAE 2014, 16, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Xie, L.-F.; Qian, J.-G.; Jin, Z.-Y. Study on the Solution to and Influencing Factors of Loosening Soil Pressure of Shallow Buried Loess Shield Tunnels. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2024, 61, 454–465. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.-B.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.-X.; Wang, C.-W. Method for Calculating Pressure of surrounding soil in Loess Tunnels. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 47, 1210–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.-H.; He, H.-N.; Lan, K.-J.; Li, Y.-B. Influences of Increase of Moisture Content on Surrounding Soil Pressure of Large-span Tunnels in Loess. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 43, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.-X.; He, J.-W.; Zheng, G.-W.; Zhou, Q.-C.; Shi, L.-X.; Gao, X.-M.; Yang, Y.-W. Analysis of the Load Bearing Mechanism and Mechanical Properties of the Advanced Pipe Roof and Discussion on Its Engineering Application. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2025, 62, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Guo, X.-H.; Wang, L.-C.; Yang, J.-K.; Sun, D.-S. Experimental Study on Bearing Characteristics and Support Parameters of Tunnel Pipe-Roof Supports. Tunn. Constr. 2024, 44, 1554–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.-Y. Mechanical Response Characteristics and Engineering Applications of Advance Long-Pipe Roofs for Tunnels. Tunn. Constr. 2025, 45, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Wang, S.-T.; Wang, J.-F.; Zhang, D.; Chen, P.; Pan, H.; Li, A. Mechanical Behaviors and Supporting Effect Evaluation of Pipe Roof in Tunneling Engineering Considering Micro-arch Effects. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 45, 561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Itasca Consulting Group. FLAC 3D Version 6, User’s Guide; Itasca Consulting Group: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Wang, W.-Z.; Yang, X.-C. Using FLAC3D to Study the Influence Range of Underground Mining on Surrounding Rock. Nonferrous Met. 2009, 61, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.-R.; Pu, S.; Xiang, C.-Z.; Yu, T.; Yao, Z.-G.; Xiang, L. Study on Excavation Disturbance Characteristics and Rockburst Mechanism of Horizontal Layered Hard Rock Tunnel under High Geostress. Highway 2025, 70, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.-Z.; Wu, Y.-J.; Wang, W.; Tang, Y. Analysis of Influence of Excavation Spatial Effect on Large-section Soft Rock Tunnel. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2021, 17, 511–519. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.-Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.-Y.; Cheng, Z.-Q.; Yang, D.-H. Study on Solving Accuracy of Numerical Model Stability for Soil Slope. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2024, 41, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Çetindemir, O. Nonlinear Constitutive Soil Models for the Soil–Structure Interaction Modeling Issues with Emphasis on Shallow Tunnels: A Review. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 12657–12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qi, C.; Yang, J.; Luo, L. Progress and Prospect of Construction Technology for Loess Tunnels. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2024, 61, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.-N.; Dong, Y.-C.; Yu, L. Elastoplastic Analytical Solution of Surrounding Rock for Loess Tunnel Based on Bilinear Strength Criterion. China Railw. Sci. 2019, 40, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.-P.; Zhao, M.-K.; Liu, Y.-Y. Control Technology and Effect Analysis of Surrounding Rock Pressure for Shallow Buried Loess Tunnel. China J. Highw. Transp. 2024, 37, 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.-B.; Chen, Z.-M.; Ye, F.; Liang, X.; Feng, H.; Xia, T. Model Tests on Disturbance Characteristics of surrounding soil of Loess Shield Tunnels During Excavation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 46, 968–977. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.-B.; Ye, F.; Feng, H.-L.; Han, X.; Tian, C.-M.; Lei, P. Pressure of surrounding soil of Deep-buried Loess Shield Tunnel. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 43, 1271–1278+1377. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.-P.; Wang, S.-Y.; Su, C.-S.; Pan, H.-W.; Wei, S.-F. Optimization of Construction Scheme for Shallow Buried Small Clear-distance Asymmetric Section Tunnel in Loess Stratum. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2022, 54, 646–656. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, G.-J.; Liu, C.-D.; Guan, R.-S.; Huang, J.-H.; Zhang, Q. Analysis on Excavation Deformation and Surrounding Rock Stress of Shallow Buried Small Clear Distance Tunnel with Weak Interlayer. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2022, 39, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S.-H.; Cao, X.; Li, W.-P.; Lin, B.-B.; Li, X.-G. Study on the Engineering Characteristics of surrounding soil in Fault Fracture Zone and the Influence of Tunnel Construction. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2025, 21, 1038–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B.; Xu, H.; Guo, G.-H.; Xing, H.; Zhang, H.-T.; Wang, G.-Z. Analysis and Control Methods of Surface Subsidence in Shallow Buried Section of Mountain Tunnel. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 2025, 33, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Tian, H.-S.; Yang, W.-B.; Dong, M.; Zhou, Y.; You, Z. Study on Deformation and Structural Mechanical Characteristics of Tunnel Intersection Section in High Geostress Squeezing Surrounding Rock. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2024, 43, 1952–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.-L.; Yang, W.-B.; Tian, H.-S.; Kou, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.-L.; Yang, Q.-W.; He, C. Study on Deformation Control of Double-layer Initial Support in Tunnel Considering Short-term Creep Effect of Surrounding Rock. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2023, 42, 1731–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.; Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Guo, Z.; Chen, H. Replicating the sequential excavation method in tunnel model tests. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 158, 106425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | γ (kN/m3) | φ (°) | c (kPa) | ν | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 Loess | 16.5 | 27.5 | 47.5 | 0.3 | 45 MPa |

| Initial support | 24.83 | - | - | 0.24 | 28.51 GPa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Du, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; López-Almansa, F. Numerical Study of Symmetry in Tunneling-Induced Soil Arch. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122167

Meng H, Li Y, Chen H, Du X, Chen X, Zhang H, López-Almansa F. Numerical Study of Symmetry in Tunneling-Induced Soil Arch. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122167

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Haoran, Yao Li, Houxian Chen, Xuchao Du, Xingli Chen, Haoyu Zhang, and Francisco López-Almansa. 2025. "Numerical Study of Symmetry in Tunneling-Induced Soil Arch" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122167

APA StyleMeng, H., Li, Y., Chen, H., Du, X., Chen, X., Zhang, H., & López-Almansa, F. (2025). Numerical Study of Symmetry in Tunneling-Induced Soil Arch. Symmetry, 17(12), 2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122167