Resolving Spatial Asymmetry in China’s Data Center Layout: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Data Center Optimization and Green Transition

2.2. Applications of Evolutionary Game Theory

3. Model Construction

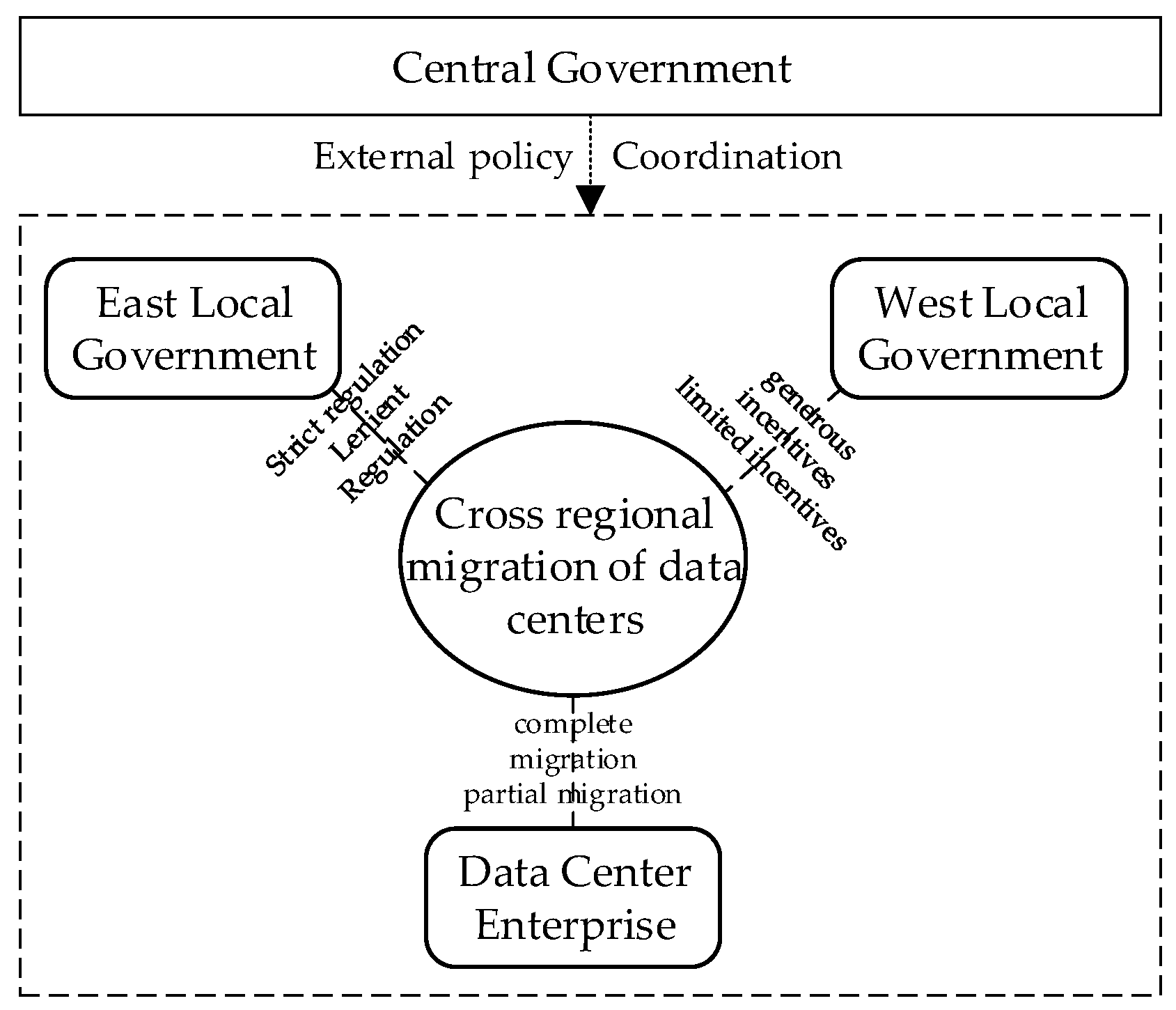

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. Model Assumptions

3.3. Parameter Definitions

- Baseline cost parameters. The eastern regulatory cost, western incentive cost, and enterprise migration cost are anchored to benchmark ranges reported in authoritative industry studies, such as those from the China Center for Information Industry Development (CCID), and complemented by relevant policy documents issued by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). In particular, the eastern regulatory cost is modeled as a largely administrative expenditure that is relatively stable in the short run and does not scale proportionally with enterprise size.

- Policy and green parameters. Policy-linked items—including the PUE-compliance subsidy, corporate carbon-quota-related costs, green-certificate-related returns, and differentiated intergovernmental transfers—are specified with reference to national “dual-carbon” policy documents, officially released market transaction indicators, and Ministry of Finance regulations. Carbon-related parameters follow the compliance-and-trading logic of China’s national Emissions Trading System (ETS) and are benchmarked to published transaction statistics for China Emission Allowances (CEA). Green attributes are aligned with the official green electricity certificate issuance and trading framework. Notably, power usage effectiveness (PUE) enters the model through the compliance concept underlying the subsidy instrument, rather than as an explicitly assigned numerical PUE value.

- Behavioral granularity parameters. To capture heterogeneous behavioral intensities, the model introduces a migration-degree coefficient and an incentive-intensity coefficient, which measure, respectively, the depth of enterprise migration and the strength of western governmental support. Although both affect incentive-related outlays, they correspond to different decision makers and operate through different payoff components.

- Societal cost parameters. Non-pecuniary costs—such as migration-related losses borne by enterprises and reputation-related losses borne by governments—are informed by established evolutionary-game studies that incorporate social and public-opinion pressures, reflecting the comprehensive considerations present in real-world decision-making.

3.4. Payoff Matrix

3.5. Expected Payoff Functions and Replicator-Dynamics Equations

4. Evolutionary Game Equilibrium Analysis

4.1. Solving for Equilibrium Points

4.2. Analysis of the Four Scenarios of Equilibrium Point Stability Strategy

4.3. Local Stability Analysis of Equilibria

5. Simulation Analysis

5.1. Parameter Settings and Initial Values

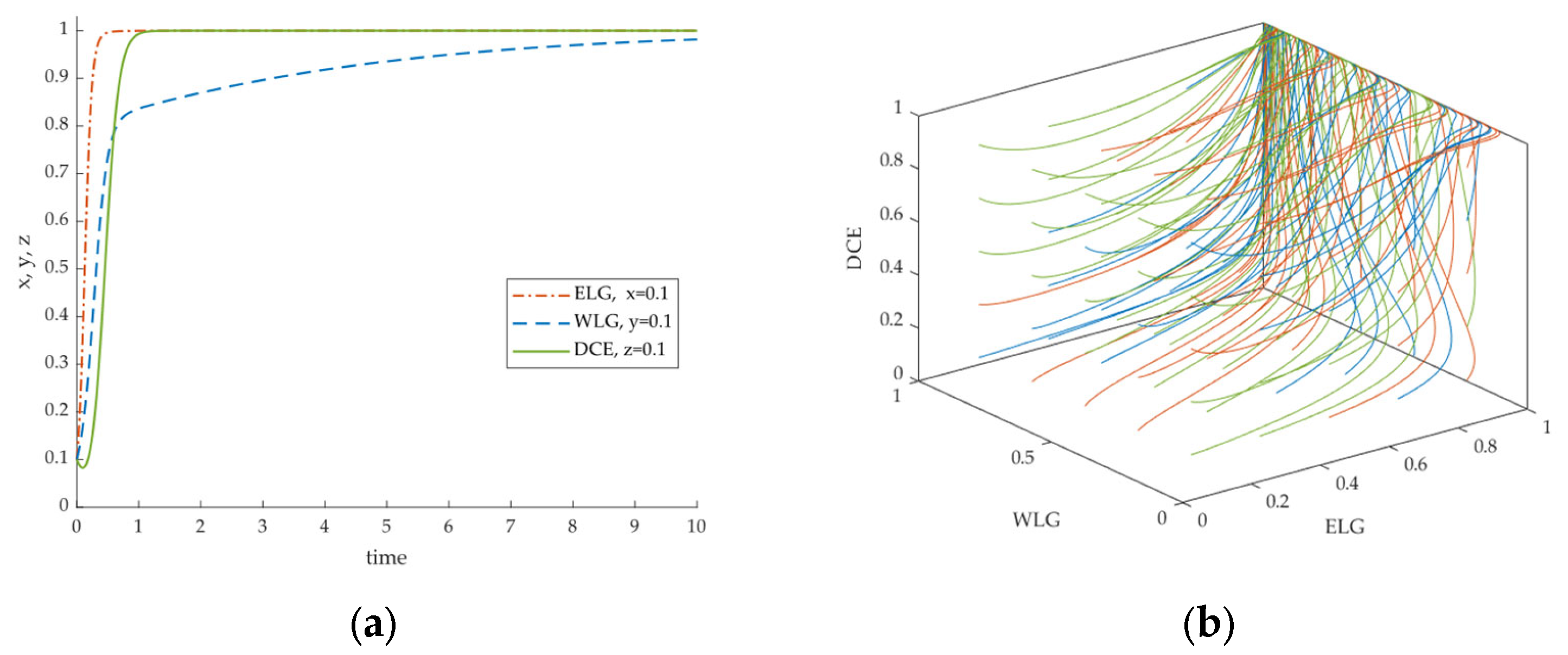

5.2. Model Stability Analysis

5.3. The Initial Willingness and Its Impact on the Strategy Evolution of the Three Parties

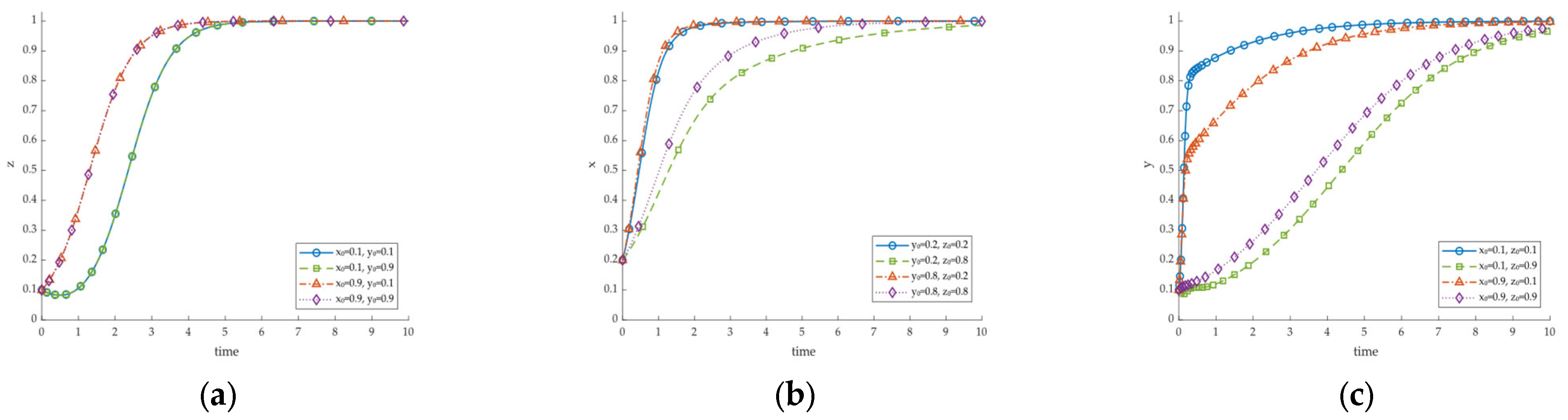

5.3.1. Impact of ELG and WLG’s Initial Willingness on DCE’s Migration Decision

5.3.2. Impact of WLG and DCE’s Initial Willingness on ELG’s Regulatory Decision

5.3.3. Impact of ELG and DCE’s Initial Willingness on WLG’s Incentive Decision

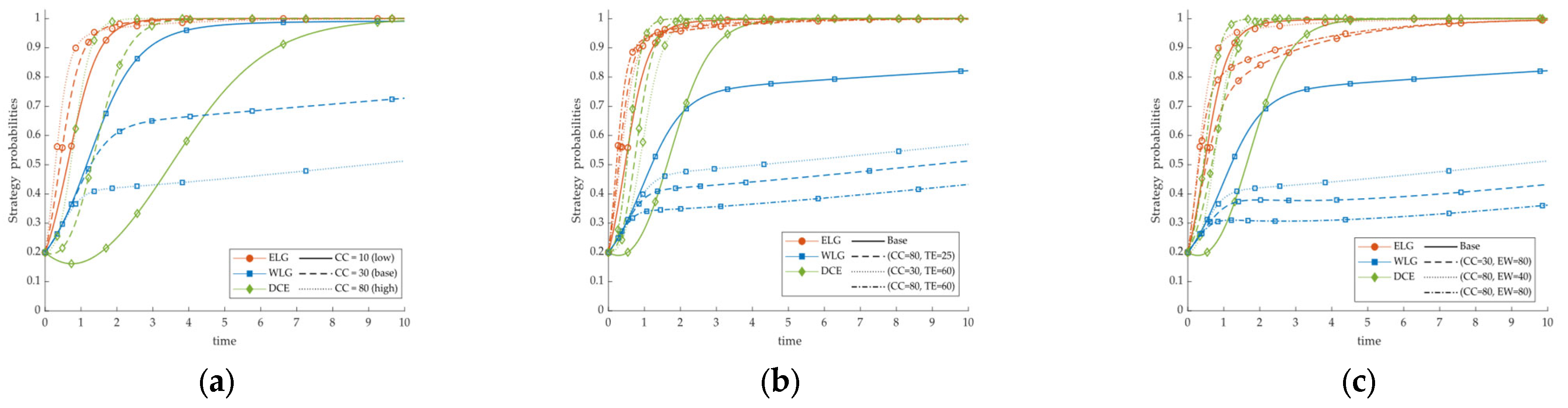

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Policy Parameters

5.4.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Carbon-Quota Cost Combined with Green Penalties and Energy Advantages (CC, TE, EW)

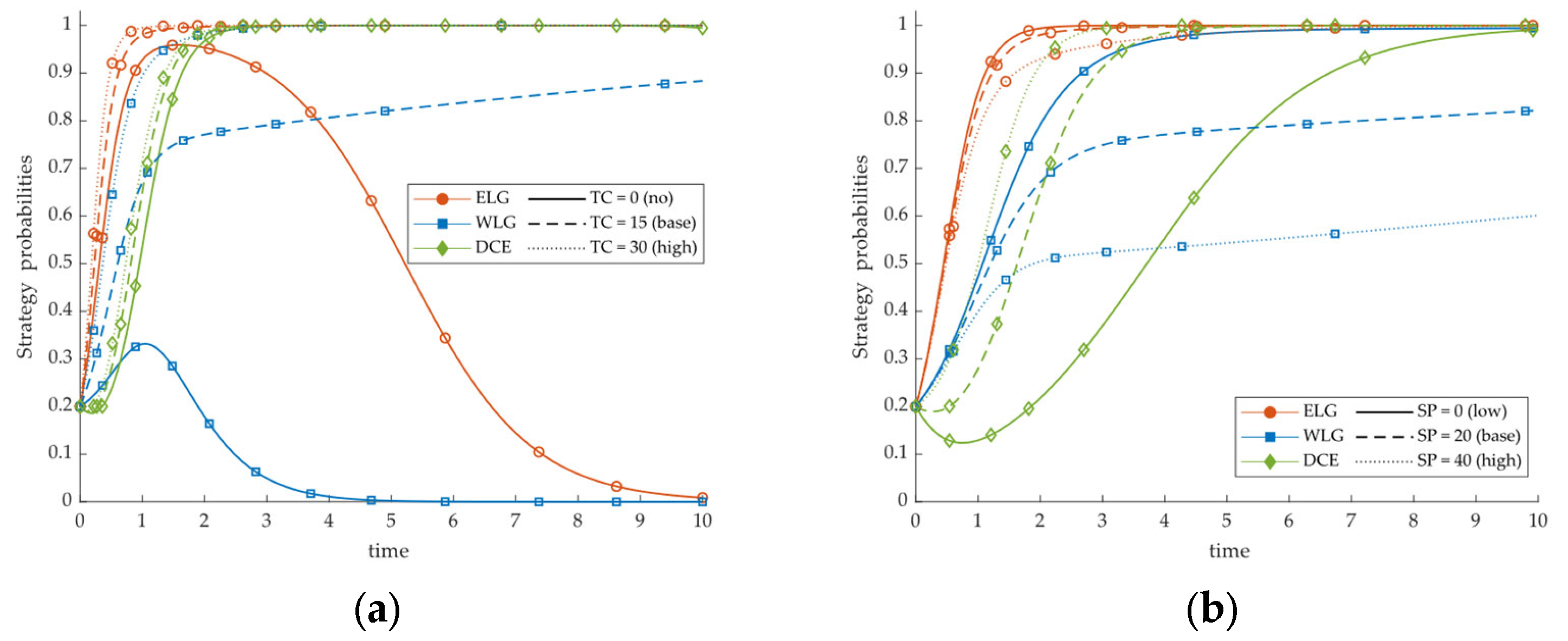

5.4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Central Penalty Cost (TC)

5.4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Central PUE-Compliance Subsidy (SP)

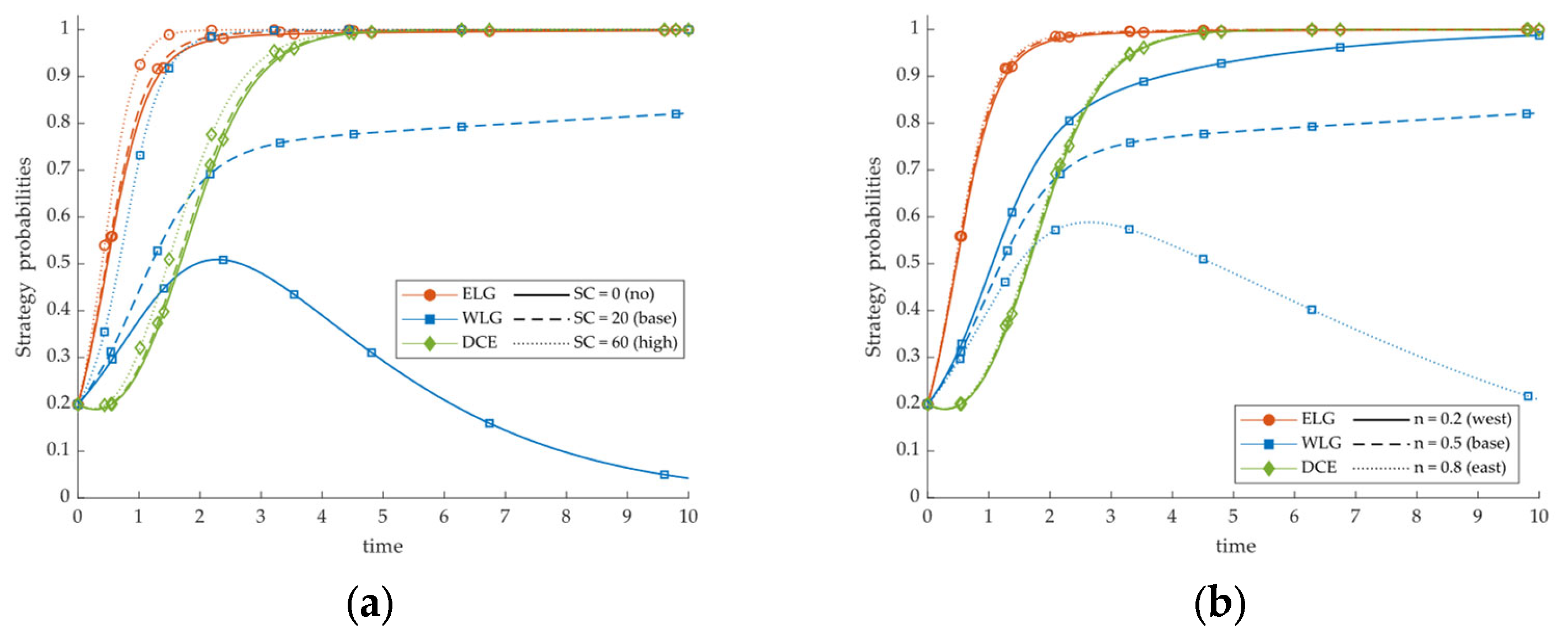

5.4.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Central Regional-Coordination Subsidy and Allocation Ratio (SC, n)

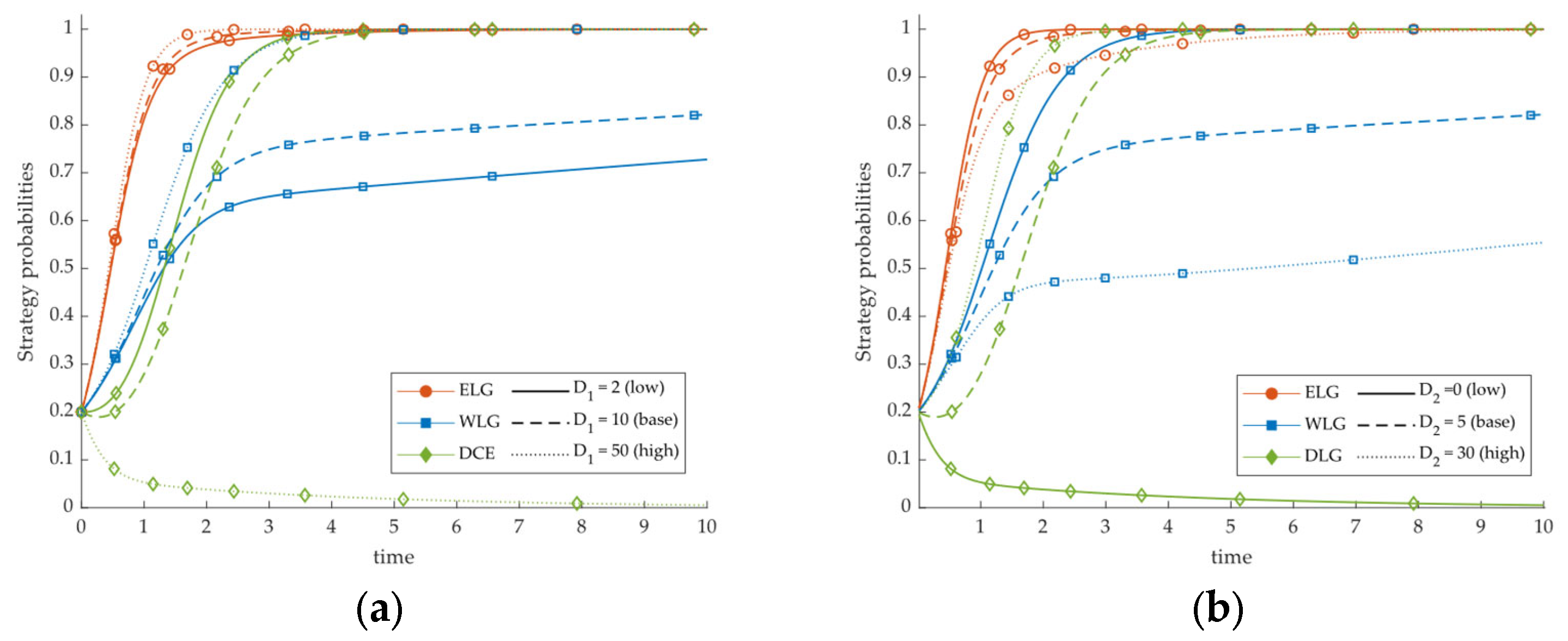

5.4.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Migration-Loss Parameters (D1, D2)

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary and Conclusions

- There exist multiple attainable equilibria and the coordinated optimum does not arise spontaneously. The system can converge to a coordinated state with strict regulation, high incentives, and complete migration; to a policy-failure state with lenient regulation, low incentives, and partial migration; or to intermediate outcomes such as a strong eastern push with weak western pull or active governments with cautious enterprises. Only when the intensities and structures of eastern regulation, western incentives, and central rewards and penalties are well aligned does the system converge stably to the coordinated optimum; otherwise it tends to remain in suboptimal or failing states.

- The eastern regulatory push is the primary driver, while western incentives and central policies amplify and calibrate these driving effects. Raising eastern carbon-quota costs and environmental penalties significantly accelerates convergence to complete migration and reduces dependence on large western subsidies, indicating that strong constraints are more effective than subsidies alone in promoting complete migration. Western energy-cost advantages and local incentives display threshold effects: below the threshold, migration costs dominate and firms prefer partial migration; above the threshold, these factors primarily affect the speed of convergence. Central penalties provide a baseline constraint on local behavior, whereas PUE-compliance and regional-coordination subsidies improve return expectations and reduce policy uncertainty, thereby accelerating coordination; excessive subsidy levels or East-skewed allocations may erode WLG’s capacity to sustain high incentives and divert the system from the ideal state.

- Migration risk is pivotal for understanding persistent partial migration under otherwise favorable policy environments. When complete migration entails substantial business-interruption and customer-loss costs and partial migration is nearly costless, firms adopt a conservative partial-migration strategy; lowering the risk of complete migration and moderately raising the opportunity cost of partial migration are necessary prerequisites for converting policy push and pull into firm action and moving the system from a partial-migration equilibrium to coordinated complete migration.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

- Eastern Local Government (ELG): Strengthen a credible regulatory push. ELG should reinforce green regulation by strictly enforcing energy-efficiency and carbon-compliance requirements and by progressively increasing compliance costs (e.g., via carbon pricing, CC) to discourage low-efficiency capacity. To avoid disruptive shocks, phased arrangements—such as time windows for technological upgrading and staged relocation—should accompany enforcement, thereby improving policy credibility and strengthening the regulatory “push”.

- Western Local Government (WLG): Build sustainable hosting competitiveness. WLG should shift from short-term subsidy competition (e.g., SG) toward long-term competitiveness in total cost and business environment. Priority should be given to expanding reliable renewable-energy supply and upgrading backbone networks and supporting services, which can reduce migration frictions and operational losses (e.g., D1, D2) and make the “pull” fiscally sustainable beyond the subsidy period. In addition, practical “migration-enablement” measures are needed, such as providing secure and standardized logistics services for server/equipment transportation and reassembly, setting up installation and commissioning support capacity, and improving cross-regional connectivity through dedicated bandwidth/peering arrangements and stability-oriented service guarantees.

- The central government: Coordinate incentives and constraints to align regions. Central-level instruments should be designed to prevent local inaction while stabilizing expectations. Coordination subsidies (e.g., SC) can be made conditional on the joint adoption of stringent regulation and meaningful incentives, and should be combined with enforceable penalties (e.g., TC) and balanced interregional transfers to align incentives without crowding out western participation. To address infrastructure bottlenecks directly, central programs can prioritize interregional backbone upgrades that reduce latency and improve transmission stability, and support “green-channel” institutional arrangements for data-center relocation (e.g., streamlined permitting and standardized technical/operational requirements for secure transportation and commissioning).

- Data-center enterprises (DCE): Reduce complete-migration risks and convert policy signals into action. To lower effective losses from complete migration, a staged relocation roadmap should be supported by risk-compensation tools (e.g., migration insurance and green financing for first movers). In parallel, strengthening cross-regional high-speed interconnection and computing-scheduling platforms and cultivating western demand for computing services can improve revenue stability after relocation. Operationally, migration plans should incorporate redundancy and service-continuity arrangements (e.g., data replication and performance-oriented network service commitments) to reduce interruption risk and customer-loss pressure during relocation.

6.3. Global Generalizability

6.4. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Parameter | Symbol | Parametric Meaning and Practical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern regulatory cost | CE | The regulatory expenditure incurred by ELG to strictly supervise data-center PUE and carbon emissions. |

| Western incentive cost | CW | The fiscal cost borne by WLG to implement incentive policies aimed at attracting data-center enterprises. |

| Western incentive intensity coefficient | m | The proportional coefficient for WLG’s fiscal cost when offering incentive policies (0 < m ≤ 1). |

| Enterprise migration degree coefficient | k | The proportion of an enterprise’s data center capacity relocated to the West relative to its total facility scale (0 < k ≤ 1). |

| Enterprise migration costs | CF | The comprehensive migration expenditure required for relocating the data center to the West, encompassing logistics and transportation (server shipping), equipment reassembly, installation and commissioning, and site/facility preparation, with the realized cost varying with the migration degree k. |

| Baseline return of eastern enterprises | RE | The baseline profit obtained when the enterprise’s data center remains fully in the East and operates normally (varying with the migration degree). |

| Western energy advantage return | EW | The economic gain from using western renewable energy—relative to eastern energy costs—when the enterprise completely relocates. |

| Western subsidy | SG | The subsidy provided by WLG to enterprises relocating to the West (varying with the incentive intensity, with SG < CW). |

| Central PUE-compliance subsidy | SP | The fiscal subsidy granted by the central government to data-center enterprises that, after complete migration, meet the required PUE standard. |

| Central regional-coordination subsidy | SC | An additional subsidy is provided by the central government when ELG adopts strict regulation and WLG offers generous incentives simultaneously, rewarding their coordinated policy interaction. |

| Coordination subsidy allocation ratio | n | The share of the central coordination subsidy allocated to ELG (0 < n ≤ 1). |

| Enterprise carbon-quota cost | CC | The cost paid by the enterprise to ELG for purchasing additional carbon quotas when, under strict regulation, partial migration leads to excess emissions from facilities remaining in the East. |

| Enterprise green certificate return | RG | The revenue obtained from green certificates when the enterprise completely relocates and uses renewable electricity in the West. |

| Central fiscal transfer to the East | BE | The fiscal transfer provided by the central government to ELG when it strictly enforces regulatory standards. |

| Central fiscal transfer to the West | BW | The fiscal transfer provided by the central government to WLG when it actively undertakes data-center projects by offering incentive policies. |

| Eastern penalty revenue | TE | The fines collected by ELG from noncompliant facilities that remain in the East after partial migration under strict regulation. |

| Central penalty cost | TC | The punitive cost imposed by the central government on ELG and WLG when they relax regulation or fail to actively undertake data-center projects. |

| Loss of complete enterprise migration | D1 | The short-term commercial losses associated with complete migration—such as service interruption risk, customer churn, and temporary service-quality degradation—potentially amplified by logistics frictions (server transportation), installation and commissioning time, and supply-chain stability during relocation. |

| Partial migration loss of enterprises | D2 | The operating loss under partial migration caused by cross-regional coordination and data transmission, where network latency, bandwidth constraints/costs, transmission stability, and data-transmission efficiency affect service quality and performance. |

| Reputational loss of ELG | SE | The social cost borne by the ELG due to reputational damage arising from environmental problems caused by lax enforcement when enterprises partially migrate. |

| Reputational loss of WLG | SW | The social cost borne by the WLG stemming from reputational damage and the negative externalities of “race-to-the-bottom” local competition triggered by generous incentives policies when enterprises completely migrate. |

Appendix A.2

| Equilibrium Point | Eigenvalues λ1, λ2, λ3 | Stability Condition |

|---|---|---|

| E1(0, 0, 0) | ||

| E2(0, 0, 1) | ||

| E3(0, 1, 0) | ||

| E4(0, 1, 1) | ||

| E5(1, 0, 0) | ||

| E6(1, 0, 1) | ||

| E7(1, 1, 0) | ||

| E8(1, 1, 1) |

References

- Qin, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Skare, M. Artificial intelligence and economic development: An evolutionary investigation and systematic review. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 1736–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilz, K.F.; Mahmood, Y.; Heim, L. Can AI Scaling Continue Through 2030? Available online: https://epoch.ai/blog/can-ai-scaling-continue-through-2030 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Data Centers Will Use Twice as Much Energy by 2030—Driven by AI. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-01113-z (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Energy and AI: Special Report. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Long-term Energy Consumption Forecasting for Data Center Industry in China. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration, Taiyuan, China, 22–24 October 2022; pp. 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, T.; Holzapfel, P.; Stobbe, L.; Grimm, A.; Nissen, N.F.; Finkbeiner, M. Toward climate neutral data centers: Greenhouse gas inventory, scenarios, and strategies. iScience 2025, 28, 11637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AI: Five Charts That Put Data-Centre Energy Use and Emissions into Context. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/ai-five-charts-that-put-data-centre-energy-use-and-emissions-into-context/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Dang, N.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, K.; Zhou, T. Coordinated transition of the supply and demand sides of China’s energy system. Renew. Sustain. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2024, 203, 114744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Yao, M.; She, G. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of data centers in China: An empirical analysis based on the geodetector model. Energy Build. 2025, 336, 115588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Duan, H.; Guan, Y.; Mao, R.; Song, G.; Yang, J.; Shan, Y. The “Eastern Data and Western Computing” initiative in China contributes to its net-zero target. Engineering 2024, 52, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fan, W.; Hong, Y.; Chen, C. A study on the comprehensive evaluation and analysis of China’s renewable energy development and regional energy development. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 635570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lv, T.; Hou, X.; Deng, X.; Li, N.; Liu, F. Spatiotemporal characteristics and influencing factors of renewable energy production in China: A spatial econometric analysis. Energy Econ. 2022, 116, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, A.; Hamilton, J.; Maltz, D.A.; Patel, P. The cost of a cloud: Research problems in data center networks. ACM SIGCOMM Comp. Commun. Rev. 2008, 39, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, D.; Radgen, P. Optimized data center site selection—Mesoclimatic effects on data center energy consumption and costs. Energy Effic. 2021, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, N.; Masanet, E. Statistical analysis for predicting location-specific data center PUE and its improvement potential. Energy 2020, 201, 117556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F. A genetic algorithm-based virtual machine scheduling algorithm for energy-efficient resource management in cloud computing. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2024, 36, e8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Zhao, L.; Yue, D.; Xie, X.; Xie, L.; Gorbachev, S.; Korovin, I.; Ge, Y. A game theory based optimal allocation strategy for defense resources of smart grid under cyber-attack. Inf. Sci. 2024, 652, 119759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, D.; Goh, H.H.; Wang, S.; Ahmad, T.; Mao, D.; Wu, T. Future data center energy-conservation and emission-reduction technologies in the context of smart and low-carbon city construction. Sust. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Han, Y.; Tan, H. Greening China’s digital economy: Exploring the contribution of the East–West Computing Resources Transmission Project to CO2 reduction. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Huang, K.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, Z. China’s green data center development: Policies and carbon reduction technology path. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Gou, Z. Towards energy-efficient data centers: A comprehensive review of passive and active cooling strategies. Energy Built Environ. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Sandoval, O.R.; Taslimi, M.S.; Sahrakorpi, T.; Amorim, G.; Pabon, J.J.G. Review of energy efficiency and technological advancements in data center power systems. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuventi, J.; Mehdizadeh, R. A critical analysis of power usage effectiveness and its use in communicating data center energy consumption. Energy Build. 2013, 64, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, N.; Azevedo, I. Power usage effectiveness in data centers: Overloaded and underachieving. Electr. J. 2016, 29, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, F.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y. Impact of computing infrastructure on carbon emissions in China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Hu, X.; Du, H.; Kang, Y.; Ju, Y.; Wang, Q. CO2 emission-mitigation pathways for China’s data centers. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 202, 107383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, S. Decarbonizing data centers through regional bits migration: A comprehensive assessment of China’s ‘eastern data, Western computing’ initiative and its global implications. Appl. Energy 2025, 392, 126020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, C.; Schossau, J.; Hintze, A. Evolutionary game theory using agent-based methods. Phys. Life Rev. 2016, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuyls, K.; Parsons, S. What evolutionary game theory tells us about multiagent learning. Artif. Intell. 2007, 171, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimar, O.; McNamara, J.M. Learning leads to bounded rationality and the evolution of cognitive bias in public goods games. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Zhang, J. Complexity analysis of a decision-making game concerning governments and heterogeneous agricultural enterprises with bounded rationality. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 140, 110220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Wang, Q.; Tang, J. Evolutionary game analysis of environmental pollution control under the government regulation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Feng, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J. A tripartite evolutionary game study of low-carbon innovation system from the perspective of dynamic subsidies and taxes. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, K.; Jia, Y. A tripartite evolutionary game analysis on China’s waste incineration projects from the perspective of responsible innovation. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yu, J. Personal Data Value Realization and Symmetry Enhancement Under Social Service Orientation: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Approach. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z. Evolutionary game of the green investment in a two-echelon supply chain under a government subsidy mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzberger, K.; Weibull, J.W. Evolutionary selection in normal-form games. Econometrica 1995, 63, 1371–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wei, X.; Liu, C. Tripartite evolutionary game analysis of shared manufacturing by manufacturing companies under government regulation mechanism. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 7706727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pauw, D.J.W.; Vanrolleghem, P.A. Practical aspects of sensitivity function approximation for dynamic models. Math. Comput. Model. Dyn. Syst. 2006, 12, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donello, M.; Carpenter, M.H.; Babaee, H. Computing sensitivities in evolutionary systems: A real-time reduced order modeling strategy. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 44, A128–A149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ELG | WLG | DCE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Migration | Partial Migration | ||

| Strict Regulation | Generous Incentives | ||

| Limited Incentives | |||

| Lenient Regulation | Generous Incentives | ||

| Limited Incentives | |||

| Scenario | Stable Equilibrium | Qualitative Description | Key Policy Lever |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | E8(1, 1, 1) | Coordinated optimum | Aligned net payoffs (effective push–pull + central support/discipline) |

| Scenario 2 | E1(0, 0, 0) | Policy failure/stalemate | Weak push/pull (insufficient central incentives/discipline) |

| Scenario 3 | E6(1, 0, 1) | Strong eastern push, weak western pull | Eastern compliance pressure dominates (migration profitable even with limited incentives) |

| Scenario 4 | E7(1, 1, 0) | Coordination impeded: active governments, cautious firms | Enterprise-side migration risk (reduce complete-migration loss; improve networks/markets) |

| Equilibrium Points | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ1, λ2, λ3 | Stability | λ1, λ2, λ3 | Stability | λ1, λ2, λ3 | Stability | λ1, λ2, λ3 | Stability | |

| E1(0, 0, 0) | ?, ?, + | unstable | −, −, − | ESS | +, ?, + | Saddle | ?, +, − | unstable |

| E2(0, 0, 1) | ?, ?, + | unstable | ?, ?, + | unstable | +, ?, − | unstable | ?, +, + | unstable |

| E3(0, 1, 0) | −, +, ? | unstable | −, +, ? | unstable | +, +, ? | unstable | −, −, ? | unstable |

| E4(0, 1, 1) | −, +, + | Saddle | −, +, + | Saddle | +, +, − | unstable | +, ?, + | unstable |

| E5(1, 0, 0) | +, −, ? | unstable | +, −, ? | unstable | −, −, ? | Saddle/ESS | −, −, − | ESS |

| E6(1, 0, 1) | +, −, + | Saddle | +, −, + | Saddle | −, −, − | ESS | −, −, + | Saddle |

| E7(1, 1, 0) | +, +, ? | unstable | +, +, ? | unstable | −, +, ? | unstable | −, −, − | ESS |

| E8(1, 1, 1) | −, −, − | ESS | +, +, + | Source | −, +, − | Saddle | −, −, + | Saddle |

| Parameter | Baseline Value | Parameter | Baseline Value | Parameter | Baseline Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE | 30 | BW | 40 | TC | 15 |

| CW | 50 | BE | 20 | TE | 25 |

| CF | 100 | SG | 40 | D1 | 10 |

| CC | 30 | SP | 20 | D2 | 5 |

| RG | 15 | SC | 20 | m | 0.4 |

| RE | 80 | SE | 10 | k | 0.5 |

| EW | 40 | SW | 10 | n | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, C.; Chen, D.; Wei, X.; Chen, Y. Resolving Spatial Asymmetry in China’s Data Center Layout: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122136

Gao C, Chen D, Wei X, Chen Y. Resolving Spatial Asymmetry in China’s Data Center Layout: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122136

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Chenfeng, Donglin Chen, Xiaochao Wei, and Ying Chen. 2025. "Resolving Spatial Asymmetry in China’s Data Center Layout: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122136

APA StyleGao, C., Chen, D., Wei, X., & Chen, Y. (2025). Resolving Spatial Asymmetry in China’s Data Center Layout: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis. Symmetry, 17(12), 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122136