Triaxiality in the Low-Lying Quadrupole Bands of Even–Even Yb Isotopes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Method

- (I)

- Axial deformations, i.e.,

- (II)

- (III)

- Since Yb isotopes are characterized by the fully symmetric proton hw irrep (see Table II of [29]), the proxy-SU(3)-predicted are unnaturally low across the entire isotopic chain (see earlier discussion in Section 1). To remedy this behavior, it is necessary to take into account the next-highest-weight (nhw) irreps in the calculation of the intrinsic deformation for each of the examined isotopes. A simple first approach is to take the average of the deformation values predicted with the use of the hw and nhw irreps (see relevant discussions in [7,46]), i.e.,where and are calculated from Equation (5).

3. Results and Discussion

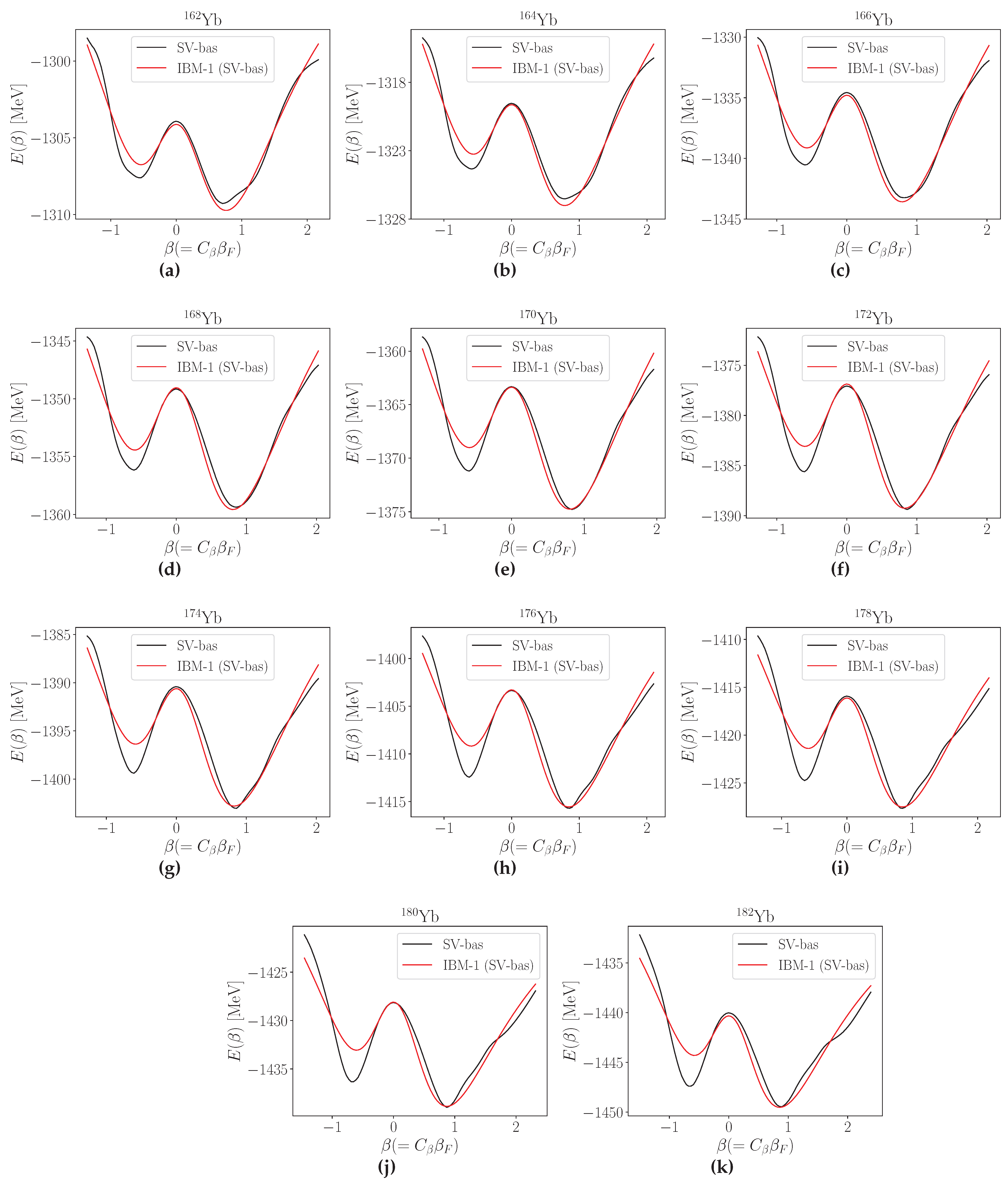

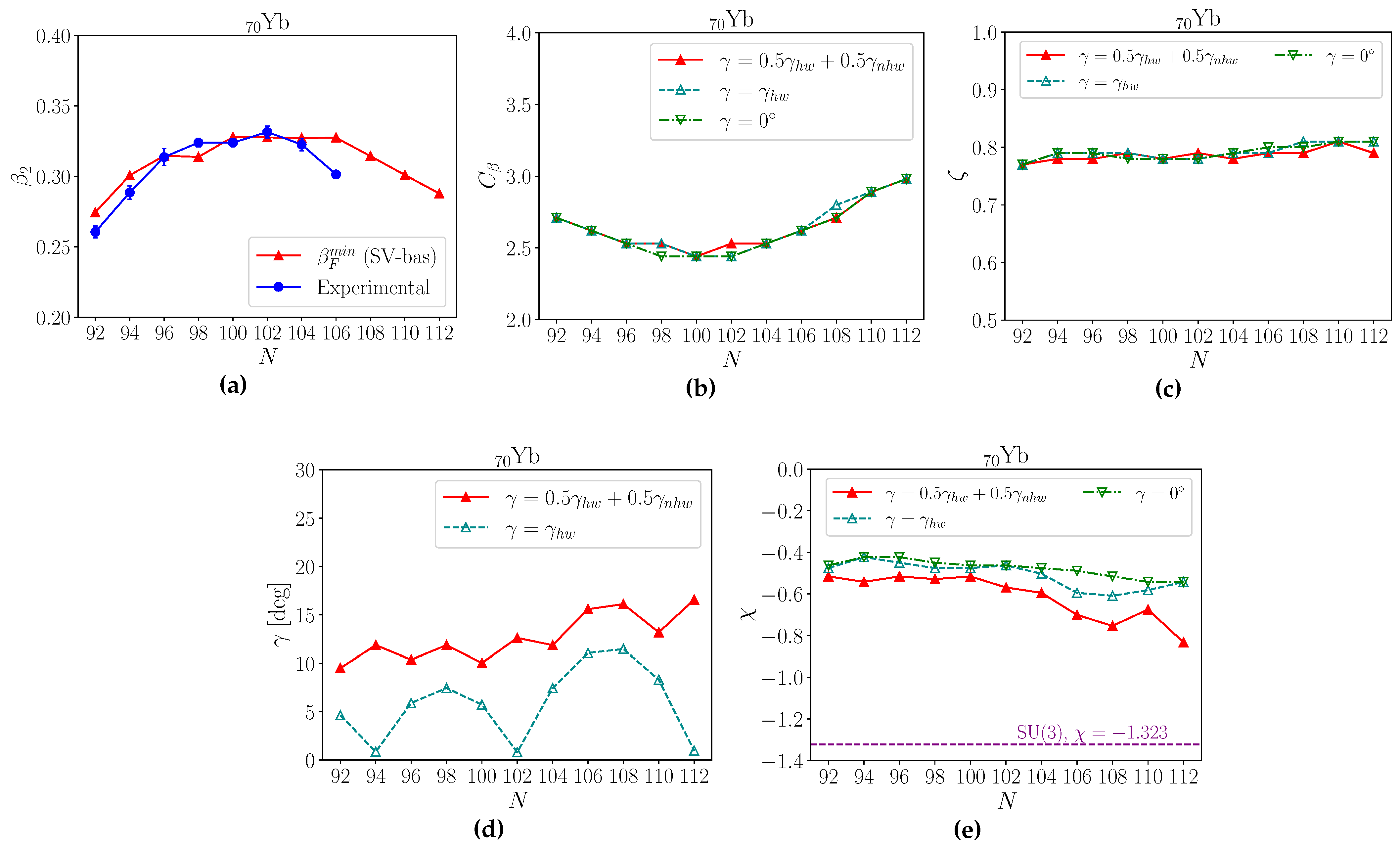

3.1. Parameter Systematics

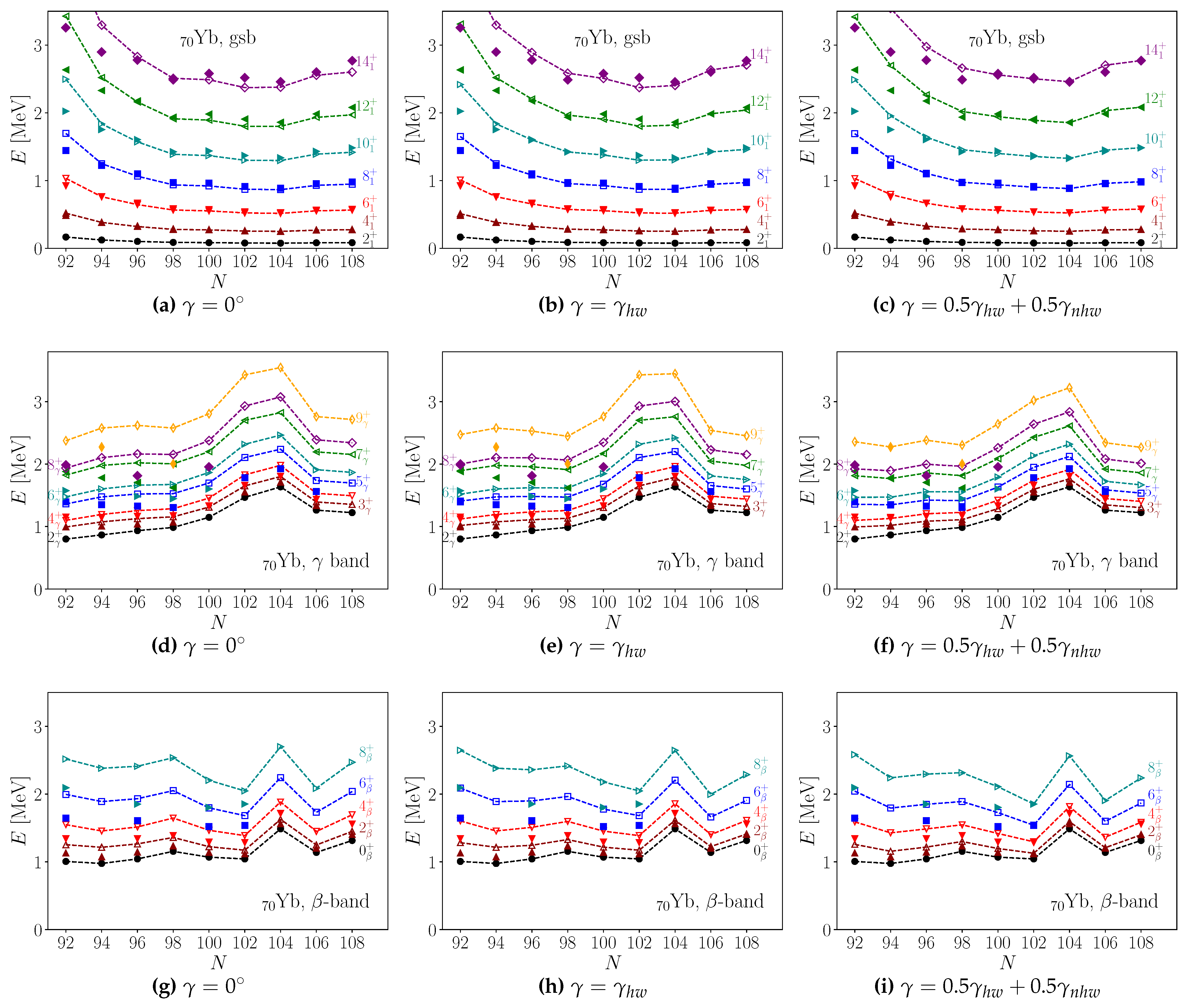

3.2. Energy Levels

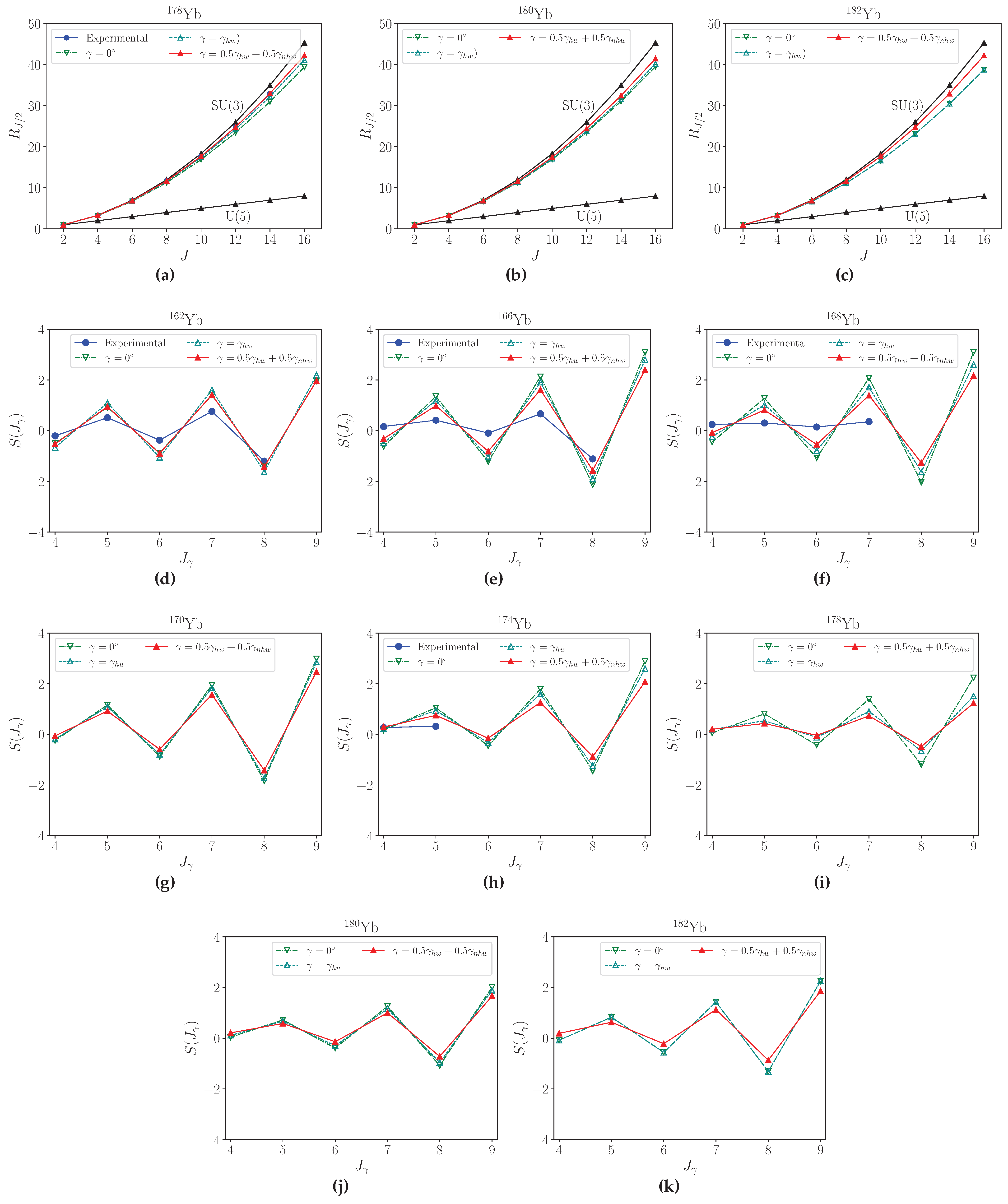

3.2.1. Ground and Bands

3.2.2. Bands

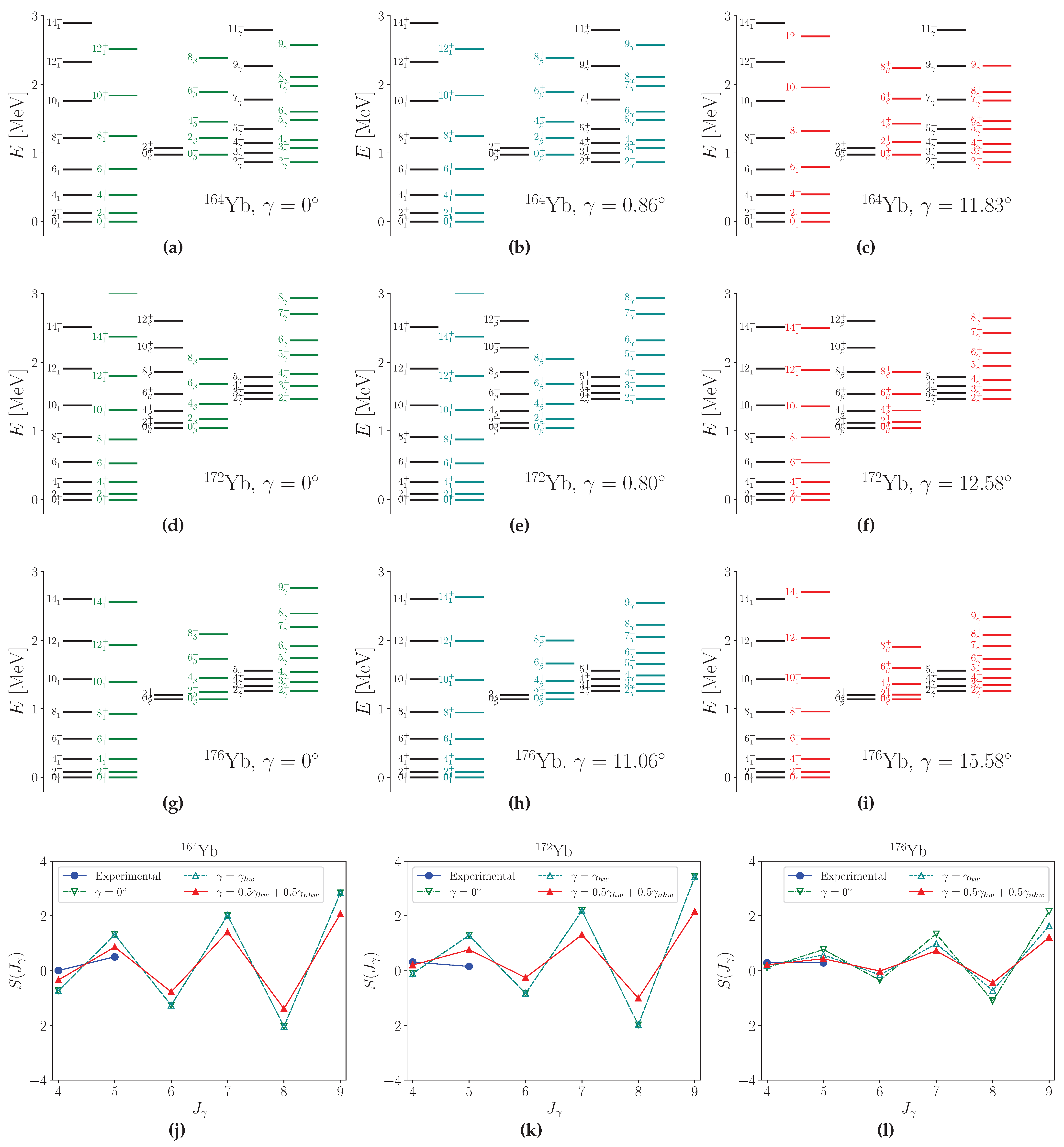

3.2.3. 164,172,182Yb94,102,112

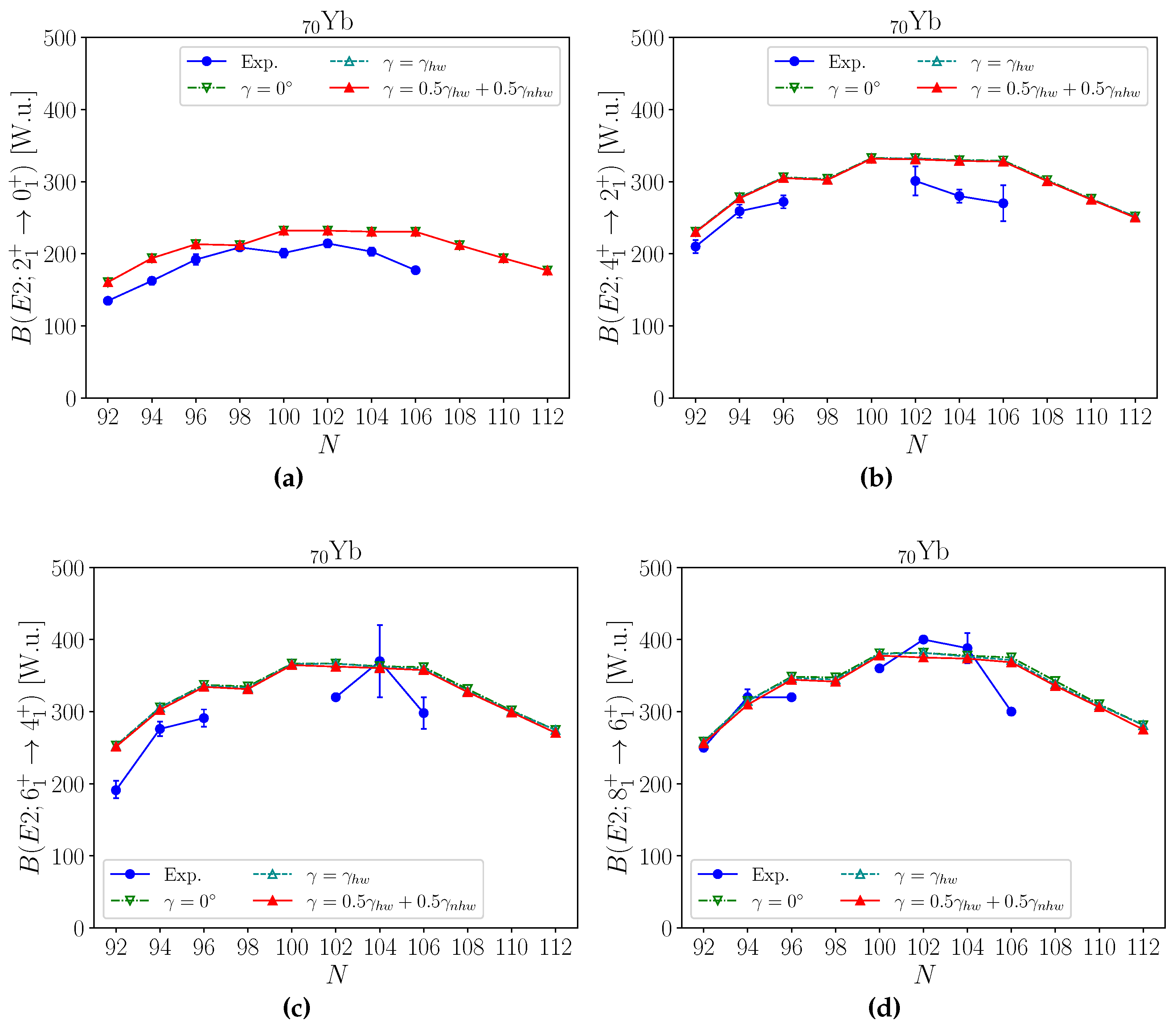

3.3. E2 Transitions

3.3.1.

3.3.2.

3.3.3.

3.4. Comparison with Monte Carlo Shell Model Predictions

4. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| irreps | irreducible representations |

| PSM | projected shell model |

| TPSM | triaxial projected shell model |

| MCSM | Monte Carlo shell model |

| hw | highest weight |

| nhw | next highest weight |

| IBM | interacting boson model |

| DS | dynamical symmetry |

| SCMF | self-consistent mean field |

| PES | potential energy surface |

| PEC | potential energy curve |

| HF+BCS | Hartree–Fock+Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer |

| CQF | consistent-Q formalism |

References

- Davydov, A.S.; Filippov, G.F. Rotational states in even atomic nuclei. Nucl. Phys. 1958, 8, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, A.S.; Rostovsky, V.S. Relative transition probabilities between rotational levels of non-axial nuclei. Nucl. Phys. 1959, 12, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-ter-Vehn, J. Collective model description of transitional odd-A nuclei: (I). The triaxial-rotor-plus-particle model. Nucl. Phys. A 1975, 249, 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunoda, Y.; Otsuka, T. Triaxial rigidity of 166Er and its Bohr-model realization. Phys. Rev. C 2021, 103, L021303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouoof, S.; Nazir, N.; Jehangir, S.; Bhat, G.H.; Sheikh, J.A.; Rather, N.; Frauendorf, S. Fingerprints of the triaxial deformation from energies and B(E2) transition probabilities of γ-bands in transitional and deformed nuclei. Eur. Phys. J. A 2024, 60, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T.; Tsunoda, Y.; Shimizu, N.; Utsuno, Y.; Ueno, H. Prevailing triaxial shapes in atomic nuclei and a quantum theory of rotation of composite objects. Eur. Phys. J. A 2025, 61, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatsos, D.; Martinou, A.; Peroulis, S.K.; Petrellis, D.; Vasileiou, P.; Mertzimekis, T.J.; Minkov, N. Preponderance of triaxial shapes in atomic nuclei predicted by the proxy-SU(3) symmetry. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 2025, 52, 015102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatsos, D.; Martinou, A.; Peroulis, S.K.; Petrellis, D.; Vasileiou, P.; Mertzimekis, T.J.; Minkov, N. Triaxial Shapes in Even-Even Nuclei: A Theoretical Overview. Atoms 2025, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.G.; Jensen, J.H.D. Elementary Theory of Nuclear Shell Structure; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Heyde, K.L.G. The Nuclear Shell Model; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Talmi, I. Simple Models of Complex Nuclei: The Shell Model and the Interacting Boson Model; Harwood: Chur, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, N. Recent Progress of Shell-Model Calculations, Monte Carlo Shell Model, and Quasi-Particle Vacua Shell Model. Physics 2022, 4, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, S.G. Binding states of individual nucleons in strongly deformed nuclei. Dan. Mat. Fys. Medd. 1955, 29, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, K.; Sun, Y. Projected Shell Model and High-Spin Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 1995, 4, 637–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J.A.; Hara, K. Triaxial Projected Shell Model Approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 3968–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.P. Collective motion in the nuclear shell model. I. Classification schemes for states of mixed configurations. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1958, 245, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.P. Collective motion in the nuclear shell model II. The introduction of intrinsic wave-functions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1958, 245, 562–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.P.; Harvey, M. Collective motion in the nuclear shell model III. The calculation of spectra. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1963, 272, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaños, O.; Draayer, J.P.; Leschber, Y. Shape variables and the shell model. Z. Phys. A 1988, 329, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Draayer, J.P.; Park, S.C.; Castaños, O. Shell-Model Interpretation of the Collective-Model Potential-Energy Surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 62, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wybourne, B.G. Classical Groups for Physicists; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Moshinsky, M.; Smirnov, Y.F. The Harmonic Oscillator in Modern Physics; Harwood: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, R.; Draayer, J.; Hecht, K. Search for a coupling scheme in heavy deformed nuclei: The pseudo SU(3) model. Nucl. Phys. A 1973, 202, 433–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draayer, J.P.; Weeks, K.J. Shell-Model Description of the Low-Energy Structure of Strongly Deformed Nuclei. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 51, 1422–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draayer, J.; Weeks, K. Towards a shell model description of the low-energy structure of deformed nuclei I. Even-even systems. Ann. Phys. 1984, 156, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuker, A.P.; Poves, A.; Nowacki, F.; Lenzi, S.M. Nilsson-SU3 self-consistency in heavy N=Z nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2015, 92, 024320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuker, A.P.; Retamosa, J.; Poves, A.; Caurier, E. Spherical shell model description of rotational motion. Phys. Rev. C 1995, 52, R1741–R1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonatsos, D.; Assimakis, I.E.; Minkov, N.; Martinou, A.; Cakirli, R.B.; Casten, R.F.; Blaum, K. Proxy-SU(3) symmetry in heavy deformed nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2017, 95, 064325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatsos, D.; Assimakis, I.E.; Minkov, N.; Martinou, A.; Sarantopoulou, S.; Cakirli, R.B.; Casten, R.F.; Blaum, K. Analytic predictions for nuclear shapes, prolate dominance, and the prolate-oblate shape transition in the proxy-SU(3) model. Phys. Rev. C 2017, 95, 064326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatsos, D.; Martinou, A.; Peroulis, S.K.; Mertzimekis, T.J.; Minkov, N. The Proxy-SU(3) Symmetry in Atomic Nuclei. Symmetry 2023, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.P.; Wilsdon, C.E. Collective motion in the nuclear shell model IV. Odd-mass nuclei in the sd shell. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1968, 302, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinou, A.; Bonatsos, D.; Mertzimekis, T.J.; Karakatsanis, K.E.; Assimakis, I.E.; Peroulis, S.K.; Sarantopoulou, S.; Minkov, N. The islands of shape coexistence within the Elliott and the proxy-SU(3) Models. Eur. Phys. J. A 2021, 57, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinou, A.; Bonatsos, D.; Karakatsanis, K.E.; Sarantopoulou, S.; Assimakis, I.E.; Peroulis, S.K.; Minkov, N. Why nuclear forces favor the highest weight irreducible representations of the fermionic SU(3) symmetry. Eur. Phys. J. A 2021, 57, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iachello, F.; Arima, A. The Interacting Boson Model; Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Arima, A.; Iachello, F. Interacting boson model of collective nuclear states II. The rotational limit. Ann. Phys. 1978, 111, 201–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, A.; Iachello, F. Interacting boson model of collective states I. The vibrational limit. Ann. Phys. 1976, 99, 253–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, A.; Iachello, F. Interacting boson model of collective nuclear states IV. The O(6) limit. Ann. Phys. 1979, 123, 468–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Isacker, P.; Chen, J.Q. Classical limit of the interacting boson Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev. C 1981, 24, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyde, K.; Van Isacker, P.; Waroquier, M.; Moreau, J. Triaxial shapes in the interacting boson model. Phys. Rev. C 1984, 29, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiamova, G. The IBM description of triaxial nuclei. Eur. Phys. J. A 2010, 45, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, F.; Dai, L.R.; Draayer, J.P. Triaxial rotor in the SU(3) limit of the interacting boson model. Phys. Rev. C 2014, 90, 044310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, Y.W.; Karlsson, D.; Qi, C.; Pan, F.; Draayer, J. A theoretical interpretation of the anomalous reduced E2 transition probabilities along the yrast line of neutron-deficient nuclei. Phys. Lett. B 2022, 834, 137443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieperink, A.E.L.; Bijker, R. On triaxial features in the neutron-proton IBA. Phys. Lett. B 1982, 116, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walet, N.R.; Brussaard, P.J. A study of the SU(3)* limit of IBM-2. Nucl. Phys. A 1987, 474, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevrin, A.; Heyde, K.; Jolie, J. Triaxiality in the proton-neutron interacting boson model: Systematic study of perturbations in the SU/emph> (3) limit. Phys. Rev. C 1987, 36, 2621–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatsos, D.; Martinou, A.; Peroulis, S.K.; Petrellis, D.; Vasileiou, P.; Mertzimekis, T.J.; Minkov, N. Robustness of the Proxy-SU(3) Symmetry in Atomic Nuclei and the Role of the Next-Highest-Weight Irreducible Representation. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, P.; Bonatsos, D.; Mertzimekis, T.J. Mean-field-derived IBM-1 Hamiltonian with intrinsic triaxial deformation. Phys. Rev. C 2024, 110, 014313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, P.; Bonatsos, D.; Mertzimekis, T.J. Triaxiality in Er isotopes in the framework of IBM-1. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 055306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginocchio, J.N.; Kirson, M.W. Relationship between the Bohr Collective Hamiltonian and the Interacting-Boson Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 44, 1744–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieperink, A.E.L.; Scholten, O.; Iachello, F. Classical Limit of the Interacting-Boson Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 44, 1747–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Shimizu, N.; Otsuka, T. Mean-Field Derivation of the Interacting Boson Model Hamiltonian and Exotic Nuclei. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 142501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Shimizu, N.; Otsuka, T. Formulating the interacting boson model by mean-field methods. Phys. Rev. C 2010, 81, 044307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Otsuka, T.; Shimizu, N.; Guo, L. Microscopic formulation of the interacting boson model for rotational nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2011, 83, 041302(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, P.G.; Schuetrumpf, B.; Maruhn, J. The Axial Hartree–Fock + BCS Code SkyAx. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 258, 107603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goriely, S.; Hilaire, S.; Girod, M.; Péru, S. First Gogny-Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov Nuclear Mass Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 242501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartree–Fock–Bogoliubov Results Based on the Gogny Force. 2006. Available online: https://www-phynu.cea.fr/science_en_ligne/carte_potentiels_microscopiques/carte_potentiel_nucleaire_eng.htm (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- HFB+5DCH Results. 2006. Available online: https://www-phynu.cea.fr/science_en_ligne/carte_potentiels_microscopiques/tables/HFB-5DCH-table_eng.htm (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Yang, X.Q.; Wang, L.J.; Xiang, J.; Wu, X.Y.; Li, Z.P. Microscopic analysis of prolate-oblate shape phase transition and shape coexistence in the Er-Pt region. Phys. Rev. C 2021, 103, 054321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Nuclear Data Center. Available online: https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/nudat3 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- ENSDF. Available online: https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/ensdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Pritychenko, B.; Birch, M.; Singh, B.; Horoi, M. Tables of E2 transition probabilities from the first 2+ states in even–even nuclei. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 2016, 107, 1–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klüpfel, P.; Reinhard, P.G.; Bürvenich, T.J.; Maruhn, J.A. Variations on a theme by Skyrme: A systematic study of adjustments of model parameters. Phys. Rev. C 2009, 79, 034310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, D.D.; Casten, R.F. Revised Formulation of the Phenomenological Interacting Boson Approximation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 1385–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, D.D.; Casten, R.F. Predictions of the interacting boson approximation in a consistent Q framework. Phys. Rev. C 1983, 28, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, N.V.; von Brentano, P.; Casten, R.F.; Jolie, J. Test of two-level crossing at the N=90 spherical-deformed critical point. Phys. Rev. C 2002, 66, 021304(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, V.; von Brentano, P.; Casten, R.; Scholl, C.; McCutchan, E.; Krücken, R.; Jolie, J. Alternative interpretation of E0 strengths in transitional regions. Eur. Phys. J. A 2005, 25, 455–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casten, R.F. Nuclear Structure from a Simple Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, D.H.; Gilmore, R.; Deans, S.R. Phase transitions and the geometric properties of the interacting boson model. Phys. Rev. C 1981, 23, 1254–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iachello, F.; Zamfir, N.V.; Casten, R.F. Phase Coexistence in Transitional Nuclei and the Interacting-Boson Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 1191–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchan, E.A.; Bonatsos, D.; Zamfir, N.V. Connecting the X(5)-β2, X(5)-β4, and X(3) models to the shape/phase-transition region of the interacting boson model. Phys. Rev. C 2006, 74, 034306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, A.; Mottelson, B.R. Nuclear Structure; Vol. II: Nuclear Deformations; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ginocchio, J.; Kirson, M. An intrinsic state for the interacting boson model and its relationship to the Bohr-Mottelson model. Nucl. Phys. A 1980, 350, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolos, R.V.; von Brentano, P.; Pietralla, N. Generalized Grodzins relation. Phys. Rev. C 2005, 71, 044305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolos, R.V.; von Brentano, P.; Dewald, A.; Pietralla, N. Spin dependence of intrinsic and transition quadrupole moments. Phys. Rev. C 2005, 72, 024310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolos, R.V.; von Brentano, P. Mass coefficient and Grodzins relation for the ground-state band and γ band. Phys. Rev. C 2006, 74, 064307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolos, R.V.; von Brentano, P. Bohr Hamiltonian with different mass coefficients for the ground- and γ bands from experimental data. Phys. Rev. C 2007, 76, 024309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolos, R.; Kolganova, E. Derivation of the Grodzins relation in collective nuclear model. Phys. Lett. B 2021, 820, 136581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casperson, R. IBAR: Interacting boson model calculations for large system sizes. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2012, 183, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyriliou, A.; Mertzimekis, T.J.; Chalil, A.; Vasileiou, P.; Mavrommatis, E.; Bonatsos, D.; Martinou, A.; Peroulis, S.; Minkov, N. A study of some aspects of the nuclear structure in the even–even Yb isotopes. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2022, 137, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, N.V.; Casten, R.F. Signatures of γ softness or triaxiality in low energy nuclear spectra. Phys. Lett. B 1991, 260, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchan, E.A.; Bonatsos, D.; Zamfir, N.V.; Casten, R.F. Staggering in γ-band energies and the transition between different structural symmetries in nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2007, 76, 024306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprahamian, A.; Lee, K.; Lesher, S.; Bijker, R. The nature of 0+ excitations in deformed nuclei. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2025, 143, 104173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchan, E.A.; Zamfir, N.V.; Casten, R.F. Mapping the interacting boson approximation symmetry triangle: New trajectories of structural evolution of rare-earth nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2004, 69, 064306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchan, E.A.; Zamfir, N.V. Simple description of light W, Os, and Pt nuclei in the interacting boson model. Phys. Rev. C 2005, 71, 054306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchan, E.A.; Casten, R.F.; Zamfir, N.V. Simple interpretation of shape evolution in Pt isotopes without intruder states. Phys. Rev. C 2005, 71, 061301(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, A.; Knafla, L.; Frießner, G.; Häfner, G.; Jolie, J.; Blazhev, A.; Dewald, A.; Dunkel, F.; Esmaylzadeh, A.; Fransen, C.; et al. Lifetime measurements in the tungsten isotopes 176,178,180W. Phys. Rev. C 2022, 106, 024326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, J.; Werner, V.; Kern, R.; Pietralla, N.; Bucurescu, D.; Carroll, R.; Cooper, N.; Daniel, T.; Filipescu, D.; Florea, N.; et al. Evolution of E2 strength in the rare-earth isotopes 174,176,178,180Hf. Phys. Rev. C 2019, 99, 024316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, P.; Mertzimekis, T.J.; Mavrommatis, E.; Zyriliou, A. Nuclear Structure Investigations of Even–Even Hf Isotopes. Symmetry 2023, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isotope | c [MeV] | [deg] | (exp.) | (th.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Axially symmetric | ||||||||

| 162Yb | 11 | −0.463 | 0.770 | 2.286 | 2.71 | 0.00 | 2.92 | 3.11 |

| 164Yb | 12 | −0.423 | 0.790 | 1.815 | 2.62 | 0.00 | 3.13 | 3.11 |

| 166Yb | 13 | −0.423 | 0.790 | 1.680 | 2.53 | 0.00 | 3.23 | 3.15 |

| 168Yb | 14 | −0.450 | 0.780 | 1.582 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 3.27 | 3.19 |

| 170Yb | 15 | −0.463 | 0.780 | 1.677 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 3.29 | 3.23 |

| 172Yb | 16 | −0.463 | 0.780 | 1.700 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 3.31 | 3.25 |

| 174Yb | 17 | −0.476 | 0.790 | 1.833 | 2.53 | 0.00 | 3.31 | 3.27 |

| 176Yb | 16 | −0.489 | 0.800 | 1.883 | 2.62 | 0.00 | 3.31 | 3.27 |

| 178Yb | 15 | −0.516 | 0.800 | 1.808 | 2.71 | 0.00 | 3.31 | 3.27 |

| 180Yb | 14 | −0.542 | 0.810 | 1.000 | 2.89 | 0.00 | — | 3.27 |

| 182Yb | 13 | −0.542 | 0.810 | 1.000 | 2.98 | 0.00 | — | 3.25 |

| II. Triaxial, with proxy-SU(3) h.w. () | ||||||||

| 162Yb | 11 | −0.476 | 0.770 | 2.154 | 2.71 | 4.64 | 2.92 | 3.06 |

| 164Yb | 12 | −0.423 | 0.790 | 1.815 | 2.62 | 0.86 | 3.13 | 3.11 |

| 166Yb | 13 | −0.450 | 0.790 | 1.720 | 2.53 | 5.90 | 3.23 | 3.17 |

| 168Yb | 14 | −0.476 | 0.790 | 1.655 | 2.53 | 7.45 | 3.27 | 3.22 |

| 170Yb | 15 | −0.476 | 0.780 | 1.693 | 2.44 | 5.73 | 3.29 | 3.23 |

| 172Yb | 16 | −0.463 | 0.780 | 1.700 | 2.44 | 0.80 | 3.31 | 3.25 |

| 174Yb | 17 | −0.503 | 0.790 | 1.860 | 2.53 | 7.45 | 3.31 | 3.28 |

| 176Yb | 16 | −0.595 | 0.790 | 1.943 | 2.62 | 11.06 | 3.31 | 3.30 |

| 178Yb | 15 | −0.609 | 0.810 | 1.920 | 2.80 | 11.46 | 3.31 | 3.30 |

| 180Yb | 14 | −0.582 | 0.810 | 1.000 | 2.89 | 8.31 | — | 3.28 |

| 182Yb | 13 | −0.542 | 0.810 | 1.000 | 2.98 | 0.97 | — | 3.25 |

| III. Triaxial, with proxy-SU(3) h.w. + n.h.w. () | ||||||||

| 162Yb | 11 | −0.516 | 0.770 | 2.235 | 2.71 | 9.53 | 2.92 | 3.11 |

| 164Yb | 12 | −0.542 | 0.780 | 1.950 | 2.62 | 11.83 | 3.13 | 3.19 |

| 166Yb | 13 | −0.516 | 0.780 | 1.762 | 2.53 | 10.39 | 3.23 | 3.21 |

| 168Yb | 14 | −0.529 | 0.790 | 1.713 | 2.53 | 11.85 | 3.27 | 3.25 |

| 170Yb | 15 | −0.516 | 0.780 | 1.737 | 2.44 | 10.04 | 3.29 | 3.25 |

| 172Yb | 16 | −0.569 | 0.790 | 1.841 | 2.53 | 12.58 | 3.31 | 3.29 |

| 174Yb | 17 | −0.595 | 0.780 | 1.903 | 2.53 | 11.85 | 3.31 | 3.30 |

| 176Yb | 16 | −0.701 | 0.790 | 2.023 | 2.62 | 15.58 | 3.31 | 3.31 |

| 178Yb | 15 | −0.754 | 0.790 | 1.959 | 2.71 | 16.13 | 3.31 | 3.31 |

| 180Yb | 14 | −0.675 | 0.810 | 1.000 | 2.89 | 13.17 | — | 3.30 |

| 182Yb | 13 | −0.833 | 0.790 | 1.000 | 2.98 | 16.55 | — | 3.31 |

| Experimental | MCSM | T.W. () | T.W. () | T.W. () | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 164Yb | |||||

| , | |||||

| 162.4 (53) | 155 | 193.82 | 193.82 | 193.82 | |

| — | 5.6 | 9.03 | 9.03 | 7.10 | |

| — | — | 35.11 | 35.11 | 22.61 | |

| — | — | 11.10 | 11.10 | 9.51 | |

| 168Yb | |||||

| , | |||||

| 208.8 (44) | 186 | 211.75 | 211.75 | 211.75 | |

| 5.0 (7) | 1.8 | 9.02 | 8.37 | 7.36 | |

| 9.2 (10) | — | 27.31 | 23.14 | 18.79 | |

| — | — | 9.42 | 7.78 | 6.91 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vasileiou, P.; Bonatsos, D.; Mertzimekis, T.J. Triaxiality in the Low-Lying Quadrupole Bands of Even–Even Yb Isotopes. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122135

Vasileiou P, Bonatsos D, Mertzimekis TJ. Triaxiality in the Low-Lying Quadrupole Bands of Even–Even Yb Isotopes. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122135

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasileiou, Polytimos, Dennis Bonatsos, and Theo J. Mertzimekis. 2025. "Triaxiality in the Low-Lying Quadrupole Bands of Even–Even Yb Isotopes" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122135

APA StyleVasileiou, P., Bonatsos, D., & Mertzimekis, T. J. (2025). Triaxiality in the Low-Lying Quadrupole Bands of Even–Even Yb Isotopes. Symmetry, 17(12), 2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122135