Systematic Analysis of Double Gamow–Teller Sum Rules

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model-Independent and Model-Dependent Sum Rules

3. Formalism and Benchmark

3.1. Formalism: Configuration–Interaction Shell Model

3.2. Formalism: Projection After Variation of Nucleon-Pair Condensates

3.3. Formalism: Sum Rules as Expectation Values

3.4. Benchmark of and

4. Double Gamow–Teller Sum Rules

4.1. Formalism

4.2. Benchmark DGT Sum Rules

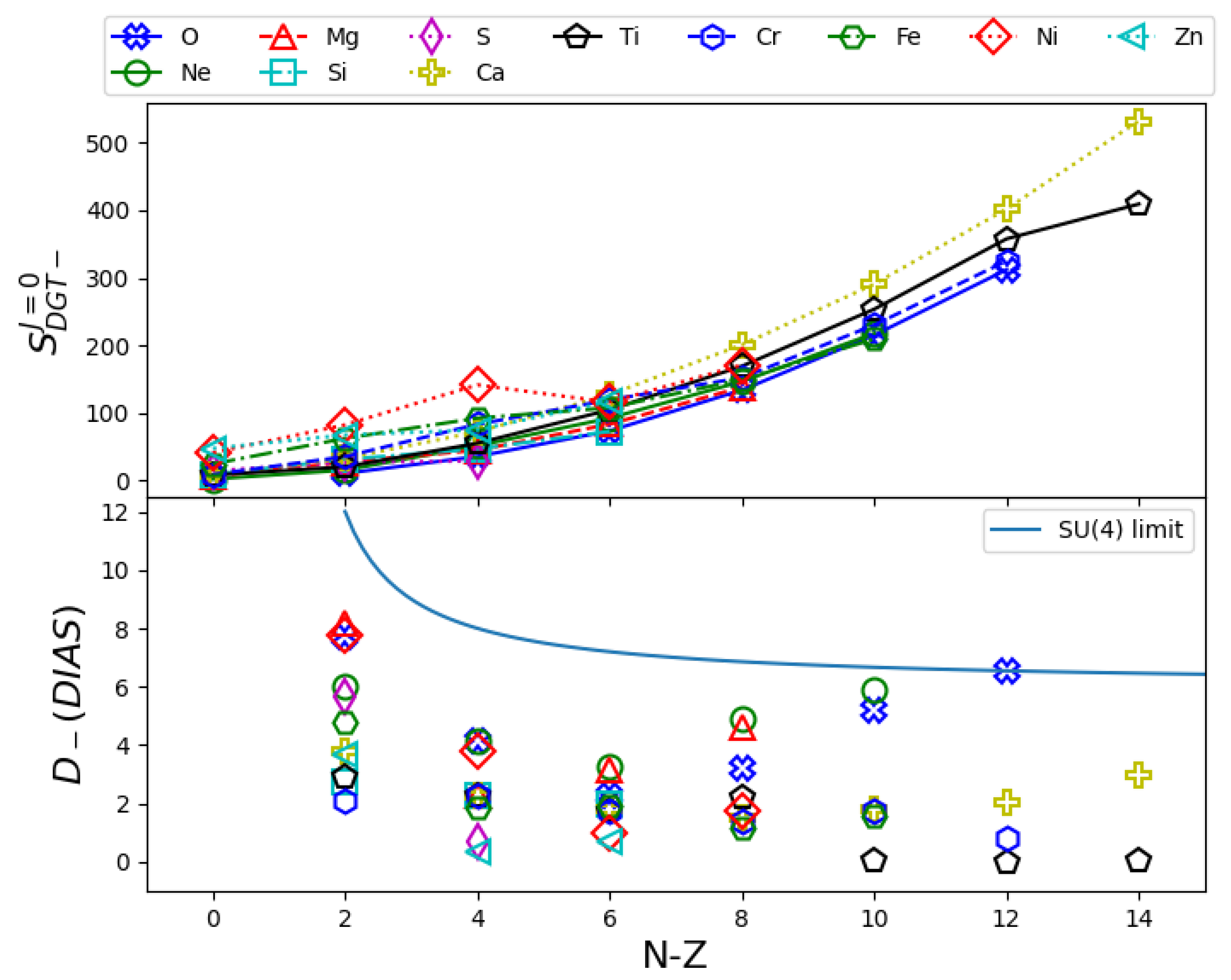

4.3. Systematic Analysis of

4.4. DGT Strength on the DIAS Final State

5. Summary and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DGT | Double Gamow–Teller |

| DGTSR | Double Gamow–Teller Sum Rule |

| DIAS | Double Isospin Analog States |

| DCX | Double Charge Exchange |

References

- Osterfeld, F. Nuclear spin and isospin excitations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1992, 64, 491–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, M.; Sakai, H.; Wakasa, T. Spin–isospin responses via (p,n) and (n,p) reactions. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2006, 56, 446–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Rubio, B.; Gelletly, W. Spin-isospin excitations probed by strong, weak and electro-magnetic interactions. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2011, 66, 549–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordechai, S.; Fred Moore, C. Double giant resonances in atomic nuclei. Nature 1991, 352, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenske, H.; Cappuzzello, F.; Cavallaro, M.; Colonna, M. Heavy ion charge exchange reactions as probes for nuclear beta-decay. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2019, 109, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuzzello, F.; Lenske, H.; Cavallaro, M.; Agodi, C.; Auerbach, N.; Bellone, J.; Bijker, R.; Burrello, S.; Calabrese, S.; Carbone, D.; et al. Shedding light on nuclear aspects of neutrinoless double beta decay by heavy-ion double charge exchange reactions. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2023, 128, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, N.; Menéndez, J.; Yako, K. Double Gamow-Teller Transitions and its Relation to Neutrinoless ββ Decay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 142502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, N.; Zamick, L.; Zheng, D.C. Double Gamow-Teller strength in nuclei. Ann. Phys. 1989, 192, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, N.; Minh Loc, B. Nuclear structure studies of double-charge-exchange Gamow-Teller strength. Phys. Rev. C 2018, 98, 064301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Maza, X.; Sagawa, H.; Colò, G. Double charge-exchange phonon states. Phys. Rev. C 2020, 101, 014320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, R.; Watt, A.; Kelvin, D. Shell-model calculation of strength functions. Phys. Lett. B 1980, 89, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caurier, E.; Martínez-Pinedo, G.; Nowacki, F.; Poves, A.; Zuker, A.P. The shell model as a unified view of nuclear structure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005, 77, 427–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevo Dinur, N.; Barnea, N.; Ji, C.; Bacca, S. Efficient method for evaluating energy-dependent sum rules. Phys. Rev. C 2014, 89, 064317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyomi, I. Collective Excitation of Unlike Pair States in Heavier Nuclei. Progr. Theoret. Phys. 1964, 31, 434–451. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, P.; Ericson, M.; Vergados, J.D. Sum rules for two-particle operators and double beta decay. Phys. Lett. B 1988, 212, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.C.; Zamick, L.; Auerbach, N. Generalization of the sum rule for double Gamow-Teller operators. Phys. Rev. C 1989, 40, 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muto, K. Sum rules for double Gamow-Teller excitation. Phys. Lett. B 1992, 277, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagawa, H.; Uesaka, T. Sum rule study for double Gamow-Teller states. Phys. Rev. C 2016, 94, 064325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.W.; Ormand, W.; Krastev, P.G. Factorization in large-scale many-body calculations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2013, 184, 2761–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kurath, D. Effective interactions for the 1p shell. Nucl. Phys. 1965, 73, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.A.; Richter, W.A. New “USD” Hamiltonians for the sd shell. Phys. Rev. C 2006, 74, 034315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, M.; Otsuka, T.; Brown, B.A.; Mizusaki, T. Shell-model description of neutron-rich pf-shell nuclei with a new effective interaction GXPF 1. Eur. Phys. J.-Hadron. Nucl. 2005, 25, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T.; Honma, M.; Mizusaki, T.; Shimizu, N.; Utsuno, Y. Monte Carlo shell model for atomic nuclei. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2001, 47, 319–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D.J.; Song, T.; Chen, H. Unified pair-coupling theory of fermion systems. Phys. Rev. C 1991, 44, R598–R601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre-Brac, B.; Piepenbring, R. Multiphonon theory: Generalized Wick’s theorem and recursion formulas. Phys. Rev. C 1982, 26, 2640–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Jiang, H.; Pittel, S. Variational approach for pair optimization in the nucleon pair approximation. Phys. Rev. C 2020, 102, 024310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Johnson, C.W.; Shen, J.J. Nuclear states projected from a pair condensate. Phys. Rev. C 2022, 105, 034317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, M.; Davies, J.; Theiler, J.; Gough, B.; Jungman, G.; Alken, P.; Booth, M.; Rossi, F.; Ulerich, R. GNU Scientific Library; Network Theory Limited: Godalming, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.Y.; Lu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Johnson, C.W.; Fu, G.J.; Shen, J.J. Shannon entropy of optimized proton-neutron pair condensates. Phys. Rev. C 2025, 111, 024310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.W. Systematics of strength function sum rules. Phys. Lett. B 2015, 750, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Johnson, C.W. Transition sum rules in the shell model. Phys. Rev. C 2018, 97, 034330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.W.; Luu, K.A.; Lu, Y. Exact sum rules with approximate ground states. J. Phys. Nucl. Part. Phys. 2020, 47, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, S.M.; Frye, H.C.; Johnson, C.W. Benchmarking angular-momentum projected Hartree–Fock as an approximation. J. Phys. Nucl. Part. Phys. 2021, 48, 095107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, H.; Adachi, T.; Bai, C.L.; Algora, A.; Berg, G.P.A.; von Brentano, P.; Colò, G.; Csatlós, M.; Deaven, J.M.; et al. Observation of Low- and High-Energy Gamow-Teller Phonon Excitations in Nuclei. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 112502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, H.; Adachi, T.; Susoy, G.; Algora, A.; Bai, C.L.; Colò, G.; Csatlós, M.; Deaven, J.M.; Estevez-Aguado, E.; et al. High-resolution study of Gamow-Teller excitations in the 42Ca(3He,t)0.28em0ex42Sc reaction and the observation of a “low-energy super-Gamow-Teller state”. Phys. Rev. C 2015, 91, 064316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Sagawa, H.; Sasano, M.; Uesaka, T.; Hagino, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, F. Role of T=0 pairing in Gamow–Teller states in N=Z nuclei. Phys. Lett. B 2013, 719, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial State | J = 0 | J = 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 6He | 12.00 (12) | 0.013 (0) |

| 8He | 39.54 (39.7) | 81.39 (80.7) |

| 14C | 7.57 (8.98) | 10.87 (7.55) |

| 18O | 10.42 (10.4) | 3.99 (3.96) |

| 20O | 33.77 (35.5) | 91.2 (91.3) |

| 42Ca | 8.50 (8.5) | 8.75 (8.75) |

| 44Ca | 31.68 (32.6) | 100.8 (98.5) |

| 46Ca | 70.38 (72.3) | 274.0 (269.3) |

| 48Ca | 125.75 (135.5) | 525.6 (501.2) |

| 18O | 22Ne | 26Mg | 30Si | 34S | 38Ar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42Ca | 46Ti | 50Cr | 54Fe | 58Ni | 62Zn | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, H.-J.; Lu, Y.; Liang, S.-Y.; Lei, Y.; Johnson, C.W. Systematic Analysis of Double Gamow–Teller Sum Rules. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122134

Xie H-J, Lu Y, Liang S-Y, Lei Y, Johnson CW. Systematic Analysis of Double Gamow–Teller Sum Rules. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122134

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Hong-Jin, Yi Lu, Shu-Yuan Liang, Yang Lei, and Calvin W. Johnson. 2025. "Systematic Analysis of Double Gamow–Teller Sum Rules" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122134

APA StyleXie, H.-J., Lu, Y., Liang, S.-Y., Lei, Y., & Johnson, C. W. (2025). Systematic Analysis of Double Gamow–Teller Sum Rules. Symmetry, 17(12), 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122134