A Machine Learning Approach for the Three-Point Dubins Problem (3PDP)

Abstract

1. Introduction

Paper Contributions

2. Problem Formulation and Related Work

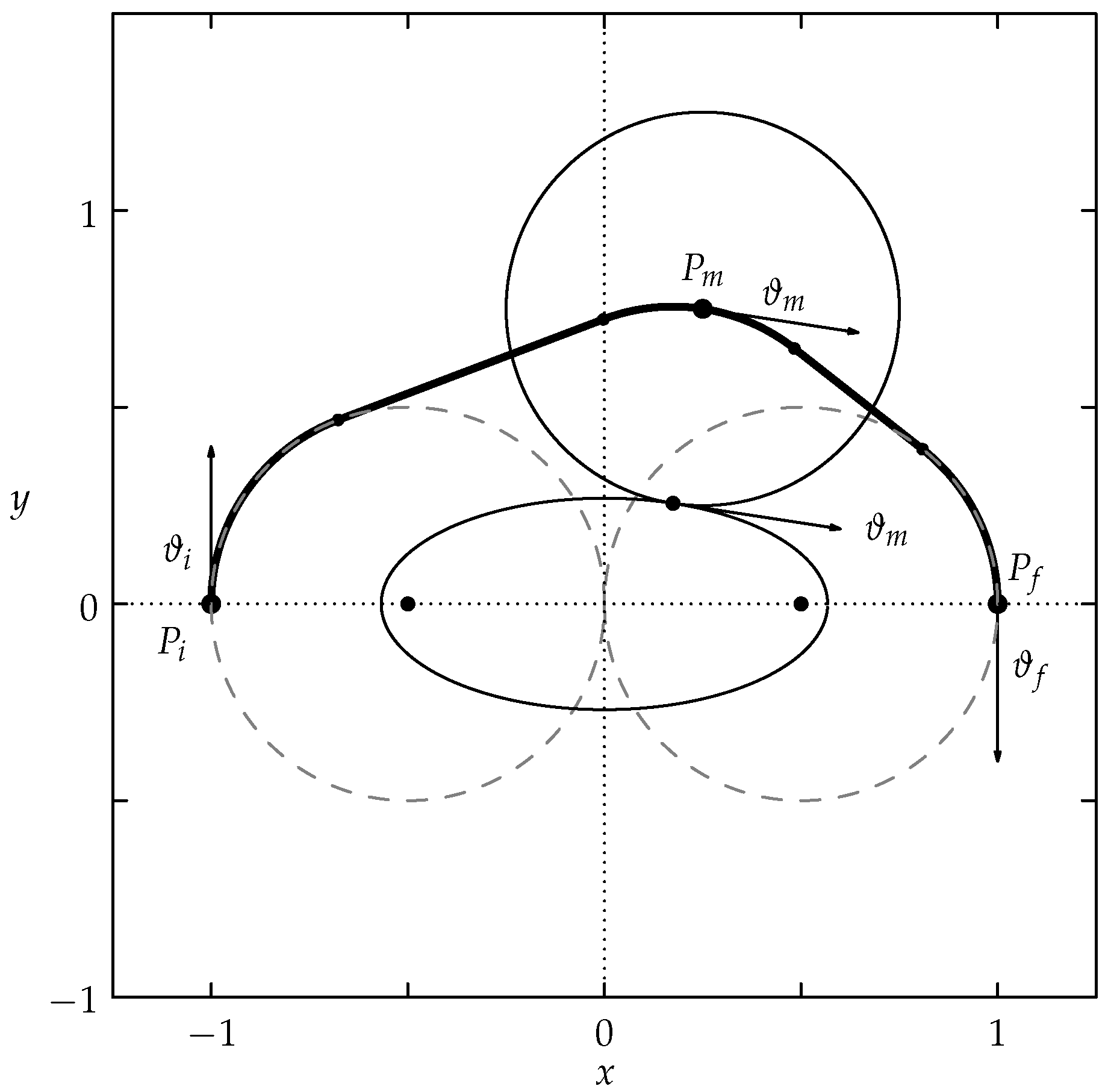

2.1. Problem Formulation and Observations

2.2. State of the Art

3. Symmetries of the Problem

3.1. Symmetries of the Markov–Dubins Problem

3.2. Symmetries of the 3PDP

4. Construction of the Training Set

- 1.

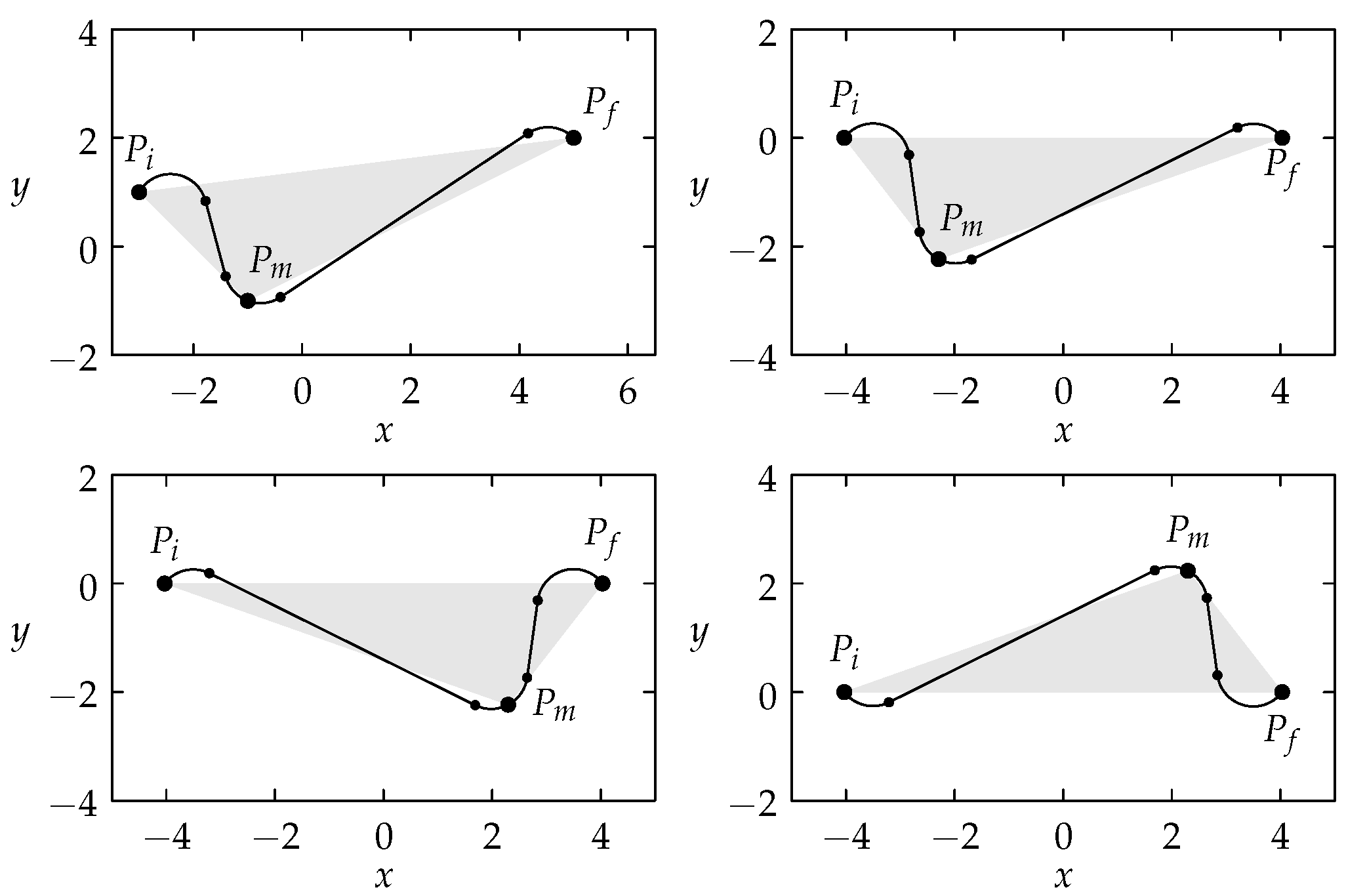

- Translate and rotate the points such that and , where (Figure 3 top right). This is conducted with the invertible map T, whereThe new angle produced by this first step, which is a solution of this rotated and shifted problem, relates to the original angle by means of .

- 2.

- After this step, can be negative; i.e., is to the left of the y-axis. We reflect the problem with respect to the vertical axis so that the new has (Figure 3 bottom left). The angle produced by this second step is .

- 3.

- At this point, can be negative; i.e., is under the x-axis. We can reflect the problem with respect to the horizontal axis so that the new has (Figure 3 bottom right). The angle produced by this third step is .

- 4.

- The problem can be further standardized by scaling the three points by a factor of . This step produces a triangle with a base from to for ; the point is mapped to the unitary square . Depending on which of the three variables realizes the maximum in r, one or more of the variables will be one. This corresponds to four cases when the triangle is acute or obtuse with “far” or “close”, specifically

- (a)

- if and , the point is contained inside the unitary square and ;

- (b)

- if and , then ;

- (c)

- if and , then and ;

- (d)

- if and , then and the maximum between the components of will be unitary.

Since this scaling operation is the same on both axes, the solution angle is not altered by this step.

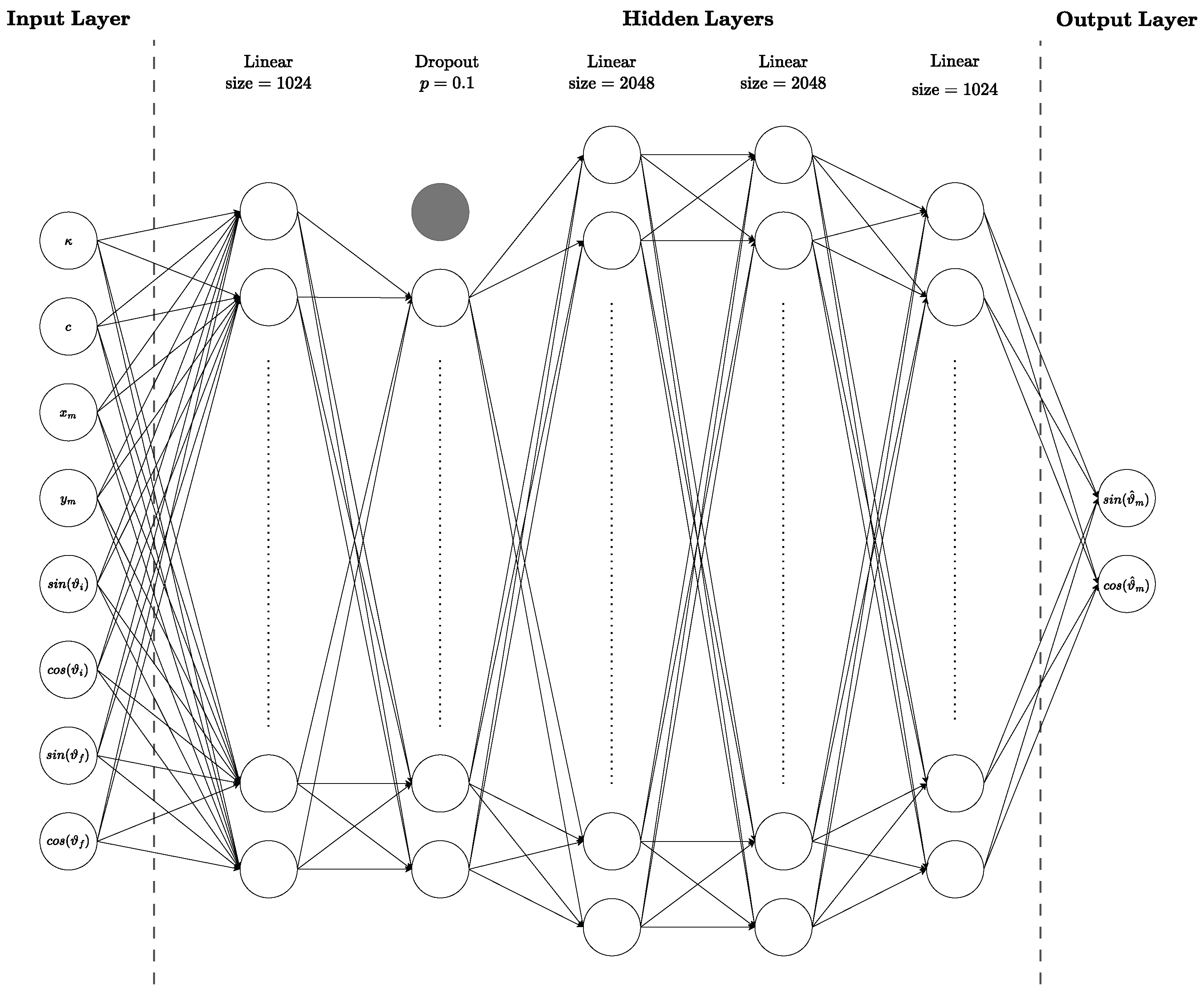

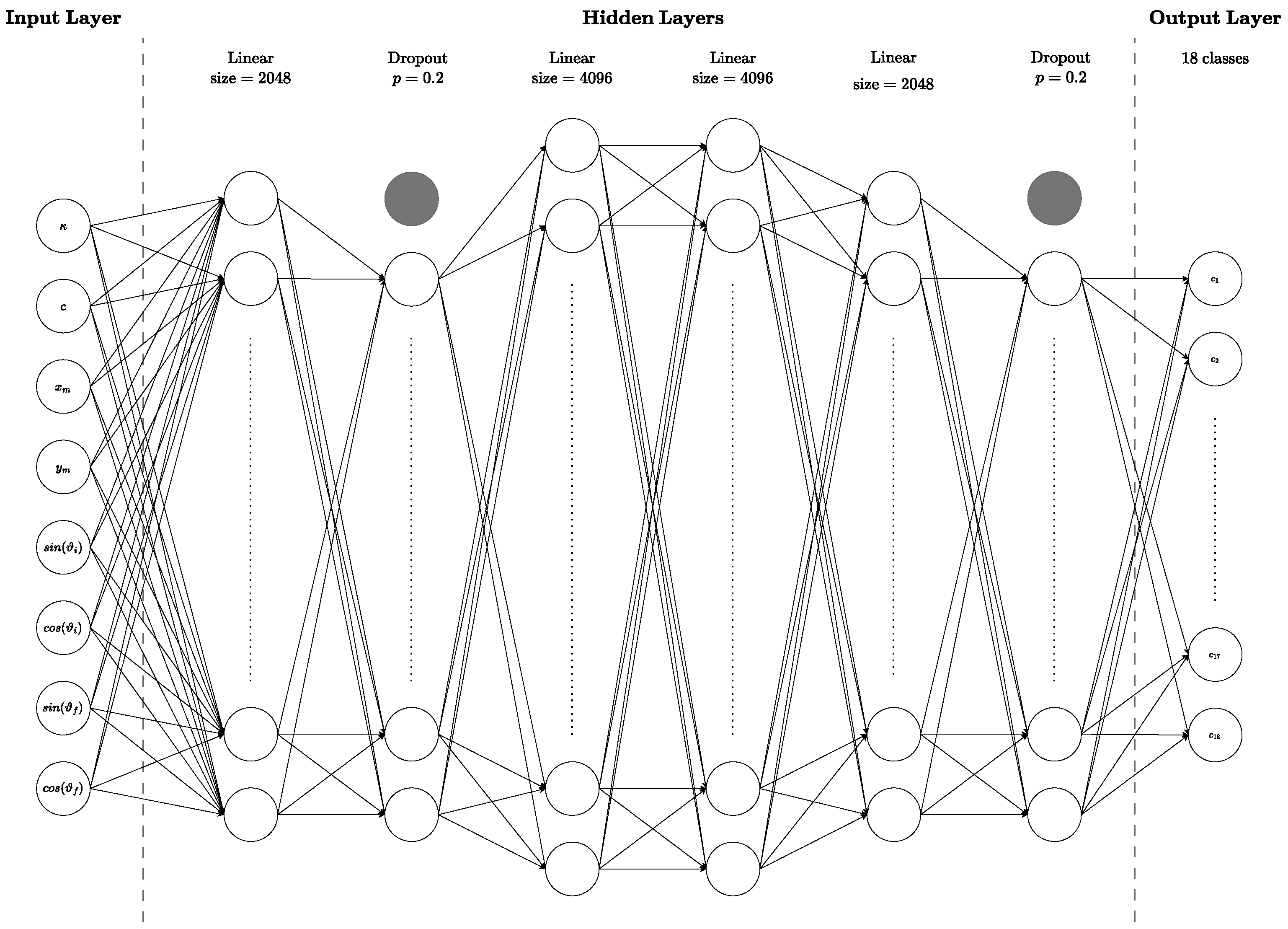

5. Training Phase

- The regression models for finding the first estimate of the optimal angle for the problem subsequently use the iterative algorithm [2] to either improve on the solution, leading to a better approximation of the optimal angle with fewer iterations, or improve the accuracy score for the same number of iterations.

- The classification model allows for identifying the type of maneuver and then computing the optimal angle by solving the corresponding polynomial formula, as shown in [19] for the PBM.

6. Results

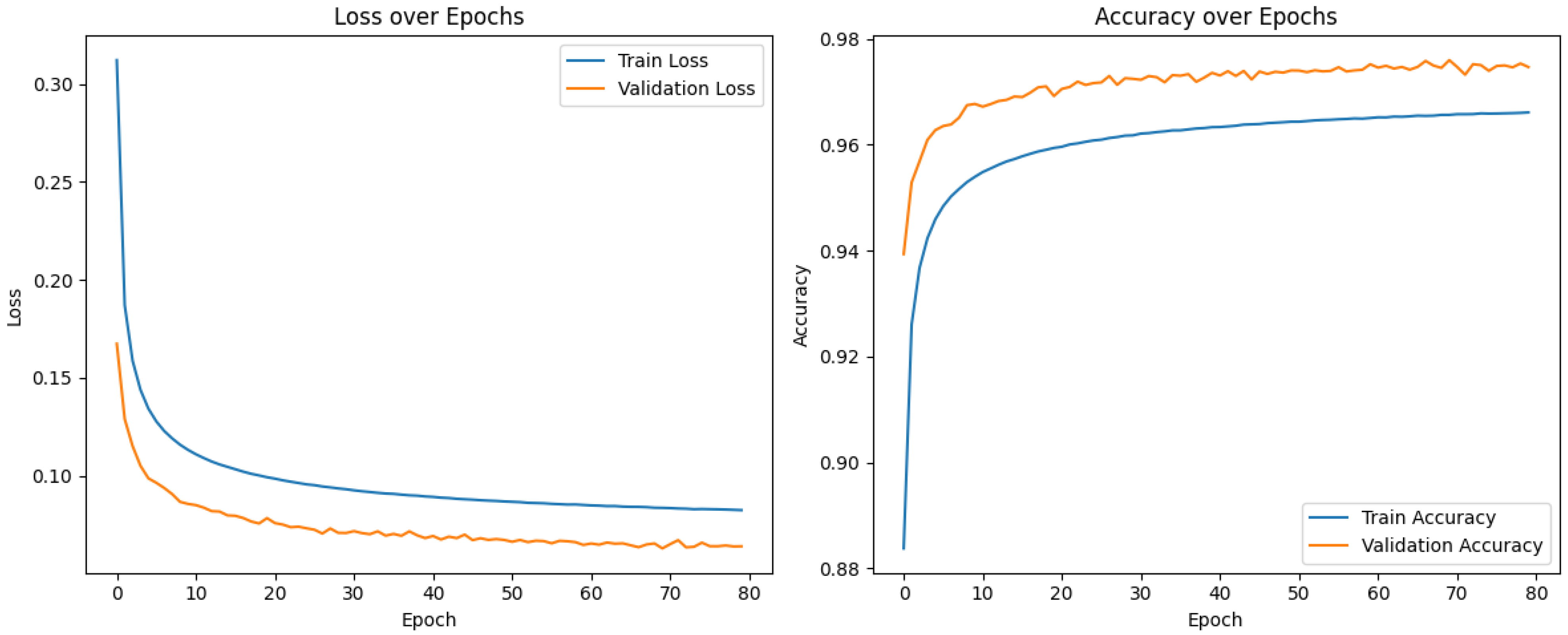

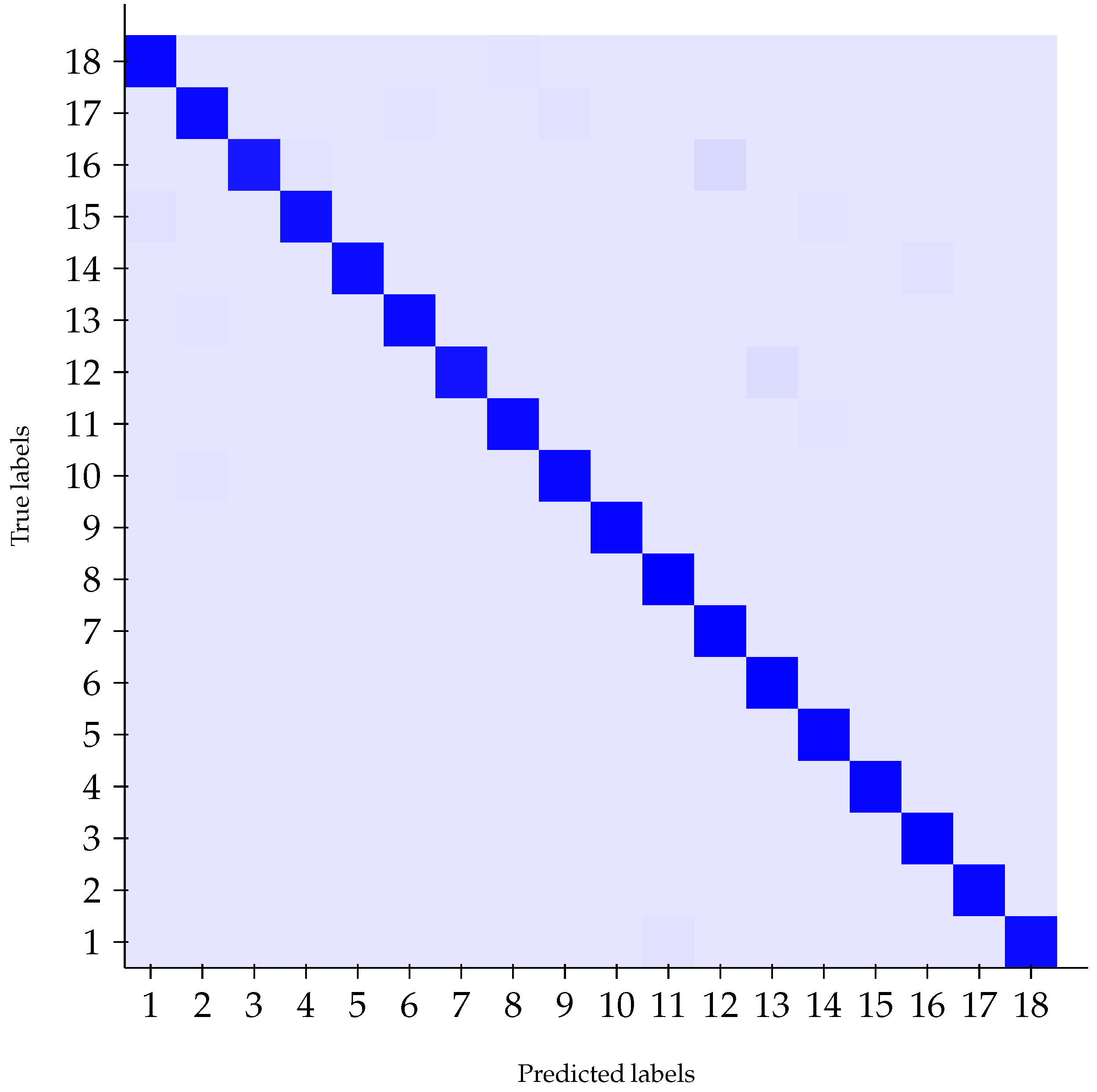

6.1. Classification Results on the Test Set

6.2. Regression Results on the Test Set

6.3. Remarks on Performance

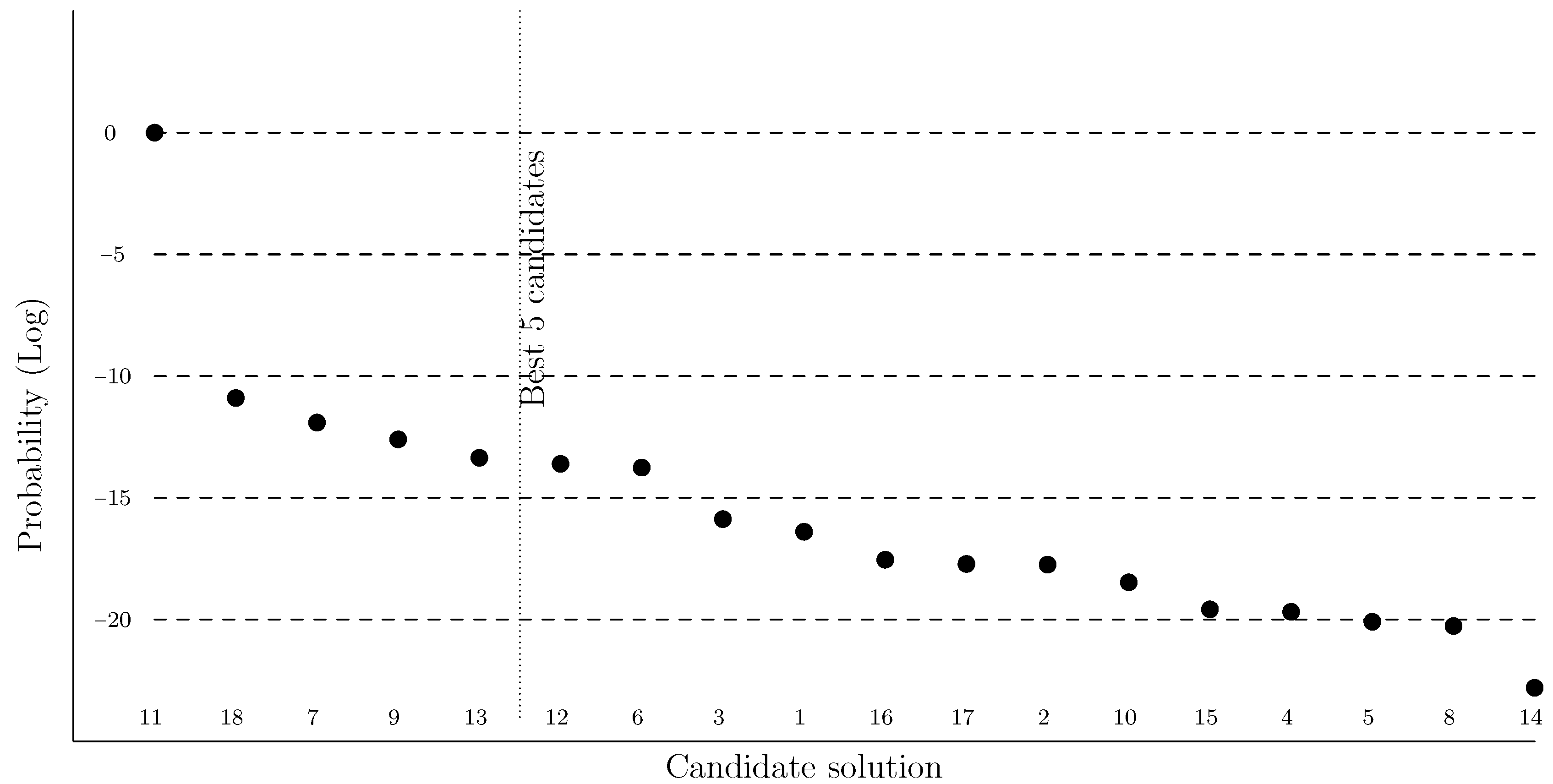

6.4. Study Case

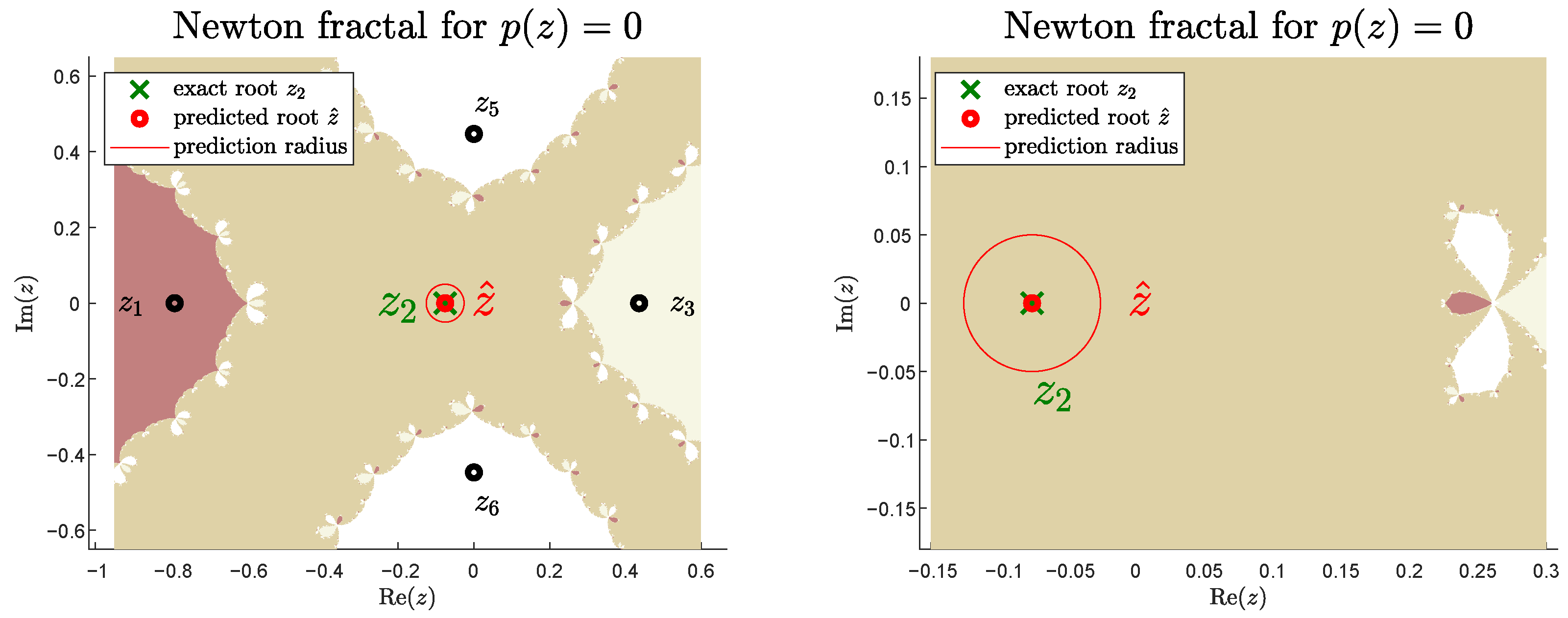

6.5. A Counterexample

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lavalle, S. Planning Algorithms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frego, M.; Bevilacqua, P.; Saccon, E.; Palopoli, L.; Fontanelli, D. An Iterative Dynamic Programming Approach to the Multipoint Markov-Dubins Problem. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 2483–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, H.; Salaris, P.; Pallottino, L. Controllability analysis of a pair of 3D Dubins vehicles in formation. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2016, 83, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlangeli, G.; De Palma, D.; Attanasi, R. A novel approach for 3PDP and real-time via point path planning of Dubins’ vehicles in marine applications. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 144, 105814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolazzi, E.; Frego, M. G1 fitting with clothoids. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2015, 38, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakolas, E.; Tsiotras, P. On the generation of nearly optimal, planar paths of bounded curvature and bounded curvature gradient. In Proceedings of the 2009 American Control Conference, St. Louis, MO, USA, 10–12 June 2009; pp. 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, P.; Frego, M.; Bertolazzi, E.; Fontanelli, D.; Palopoli, L.; Biral, F. Path planning maximising human comfort for assistive robots. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Control Applications (CCA), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 19–22 September 2016; pp. 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, P.; Dagnino, S.; Saccon, E.; Frego, M.; Palopoli, L. Fast Shortest Path Polyline Smoothing with G1 Continuity and Bounded Curvature. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 3182–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T.; Stölzle, M.; Turricelli, E.; Achermann, F.; Lawrance, N.; Siegwart, R.; Chung, J.J. Learn to Path: Using neural networks to predict Dubins path characteristics for aerial vehicles in wind. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savla, K.; Frazzoli, E.; Bullo, F. Traveling salesperson problems for the Dubins vehicle. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 1378–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ny, J.; Feron, E.; Frazzoli, E. On the Dubins Traveling Salesman Problem. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živojević, D.; Velagić, J. Path Planning for Mobile Robot using Dubins-curve based RRT Algorithm with Differential Constraints. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium ELMAR, Zadar, Croatia, 23–25 September 2019; pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Leeghim, H.; Kim, D. Dubins Path-Oriented Rapidly Exploring Random Tree* for Three-Dimensional Path Planning of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Electronics 2022, 11, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Peng, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Z. Position-based Dubins-RRT* path planning algorithm for autonomous surface vehicles. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 324, 120702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bi, C.; Liu, F.; Shan, J. Dubins-RRT* motion planning algorithm considering curvature-constrained path optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 296, 128390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeds, J.A.; Shepp, L.A. Optimal paths for a car that goes both forwards and backwards. Pac. J. Math. 1990, 145, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consonni, C.; Brugnara, M.; Bevilacqua, P.; Tagliaferri, A.; Frego, M. A new Markov–Dubins hybrid solver with learned decision trees. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Smith, S.L. On efficient computation of shortest Dubins paths through three consecutive points. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 55th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 6010–6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shima, T. Shortest Dubins paths through three points. Automatica 2019, 105, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, M.; Bertolazzi, E.; Frego, M. A Non-Smooth Numerical Optimization Approach to the Three-Point Dubins Problem (3PDP). Algorithms 2024, 17, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubins, L.E. On curves of minimal length with a constraint on average curvature, and with prescribed initial and terminal positions and tangents. Am. J. Math. 1957, 79, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussmann, H.J.; Tang, G. Shortest paths for the Reeds-Shepp car: A worked out example of the use of geometric techniques in nonlinear optimal control. Rutgers Cent. Syst. Control Tech. Rep. 1991, 10, 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, C.Y. Markov–Dubins path via optimal control theory. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2017, 68, 719–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, P.; Frego, M.; Fontanelli, D.; Palopoli, L. A novel formalisation of the Markov-Dubins problem. In Proceedings of the European Control Conference (ECC2020), St. Petersburg, Russia, 12–15 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Do Carmo, M.P. Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces; Prentice Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1976; pp. I–VIII, 1–503. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Wang, N.; Chen, T.; Li, M. Empirical evaluation of rectified activations in convolutional network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.00853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.L.; Hannun, A.Y.; Ng, A.Y. Rectifier nonlinearities improve neural network acoustic models. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–21 June 2013; 30, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Saccon, E.; Frego, M. Dataset and Models for A Machine Learning Approach for the Three-Point Dubins Problem (3PDP); Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccon, E.; Bevilacqua, P.; Fontanelli, D.; Frego, M.; Palopoli, L.; Passerone, R. Robot motion planning: Can GPUs be a game changer? In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 45th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC); IEEE; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

| CCCCC: | RLRLR, LRLRL |

| CCCSC: | RLRSR, RLRSL, LRLSL, LRLSR |

| CSCCC: | RSRLR, LSRLR, RSLRL, LSLRL |

| CSCSC: | RSRSR, LSRSR, RSRSL, LSRSL, |

| LSLSL, RSLSL, LSLSR, RSLSR |

| Method | Test Loss | MSE | Mean Angular | Accuracy (%) | F1-Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sine | Cosine | Error (Rad) | Top-1 | Top-4 | Top-5 | |||

| Classification | 0.0644 | - | - | - | 97.54 | 99.99 | 100.0 | 0.95 |

| Regression | 0.0093 | 0.0106 | 0.0079 | 0.0467 | - | - | - | - |

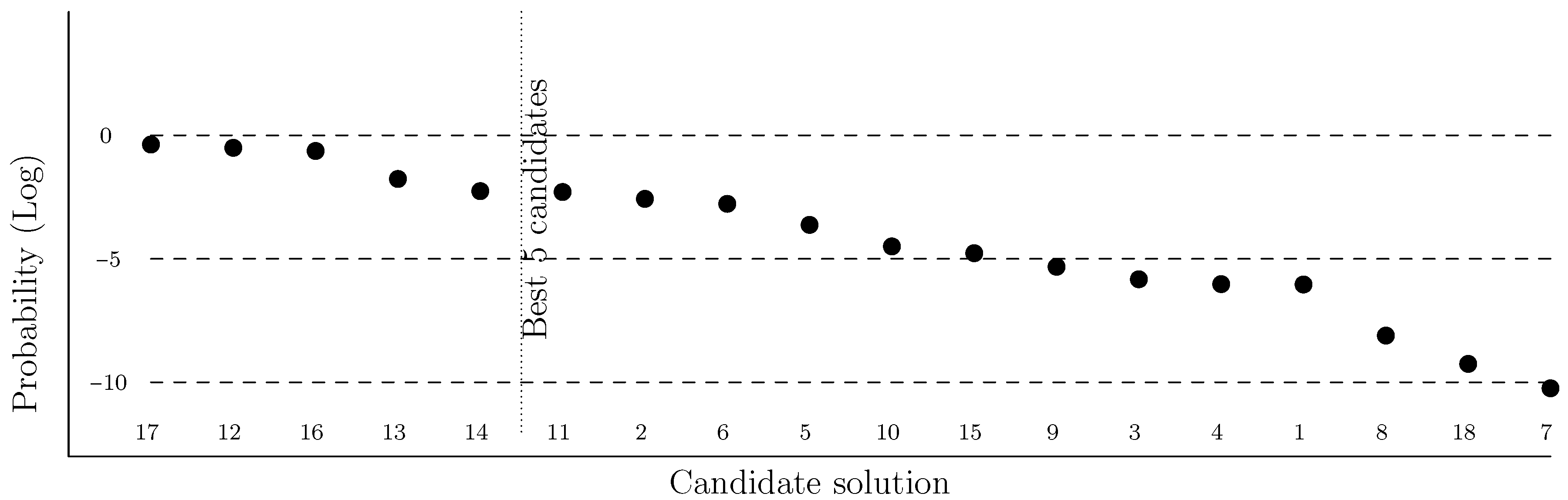

| Case | Type | Prob | L | Error on L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | RSR-RSR | 0.0050 | 5.1556 | 6.0152 | optimal |

| 17 | RSL-LSL | 0.4238 | non real | ||

| 12 | LSR-RSR | 0.3110 | −2.3797 | 6.9146 | 15% |

| 16 | RSL-LSL | 0.2327 | non real | ||

| 13 | RSR-RSL | 0.0171 | 2.6664 | 7.1440 | 19% |

| 14 | LSR-RSL | 0.0055 | 0.0176 | 9.2334 | 54% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saccon, E.; Frego, M. A Machine Learning Approach for the Three-Point Dubins Problem (3PDP). Symmetry 2025, 17, 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122133

Saccon E, Frego M. A Machine Learning Approach for the Three-Point Dubins Problem (3PDP). Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122133

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaccon, Enrico, and Marco Frego. 2025. "A Machine Learning Approach for the Three-Point Dubins Problem (3PDP)" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122133

APA StyleSaccon, E., & Frego, M. (2025). A Machine Learning Approach for the Three-Point Dubins Problem (3PDP). Symmetry, 17(12), 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122133