1. Introduction

With the development of Internet technologies, people are increasingly engaged in online activities such as social interaction, trading and remote work, resulting in massive and diverse network graph data. For decentralized networks, analyzing the connections between nodes and mining valuable information for further analysis are crucial for service providers and network operators [

1]. Typical examples include social media and trading platforms such as Odysee and the Bitcoin Network, which rely on users’ friendship or historical interaction records to recommend potential friends or products. In some real-world scenarios, directed graphs can represent relationships more precisely than undirected ones. For example, on platforms like Facebook, directed edges can denote “following” or “sharing” relationships, while in the Autonomous System level Internet, directed edges can represent provider-customer relationships—facilitating the analysis and optimization of network traffic.

Although analyzing the connections between nodes and mining valuable information for further analysis are crucial for service providers and network operators [

1], it is not easy or sometimes impossible to collect an accurate representation of the whole graph due to decentralized nature of the network or private concerns. Users are generally unwilling to disclose their contact lists, trust relationships, or transaction histories [

2]. Directly collecting such private information may violate privacy regulations [

3]. Moreover, in decentralized communication scenarios such as social networks or email systems, it is inherently difficult for servers to gather fragmented and non-global information.

Therefore, a comprised approach is to generate a global graph that closely approximates the original network based on per-user uploaded information—in a manner that preserves each user’s privacy. Local differential privacy (LDP) [

4] is a decentralized variant of differential privacy (DP) [

5] that introduces random noise into individual data points to ensure privacy and maintain the overall symmetry of the statistical distribution, and has been widely adopted. Unlike standard DP, LDP assumes there is no trusted third party: each user perturbs their own data locally to protect privacy. Using this approach, users can both protect their own privacy information and contribute data to obtain better services, and its inherent symmetric framework highlights the balance between distributed information uploading and centralized information processing. LDP is often for undirected graphs, our work extends LDP to the task of generating directed graphs based on locally perturbed user data. We assume that node attributes and similar intrinsic information are available to the server, but the edge relationships between nodes remain private.

To preserve users’ private edge relationships while maintaining the utility of the generated graph, we propose a Local Differential Privacy based Directed DGG-LDP (Directed Graph Generation With Local Differential Privacy), which guarantees user privacy while producing synthetic graphs with high data utility. When handling edge direction, we enforce the practical constraint that, under LDP, each user can only perturb information that is locally observable—typically their own out-adjacency (outgoing links) representing connections they initiated. Incoming links are controlled by other nodes and are often not publicly observable in decentralized or privacy-preserving settings; for example, on blockchain platforms a user knows to whom he sends funds (outgoing edges) but cannot directly observe who else may be interacting with his address. Based on this realistic assumption, we focus on collecting out-degree edges in the first round of information gathering. Starting with intrinsic node information and drawing on ideas from graph structure learning, we iteratively update the synthetic graph by combining low-noise signals with an initial graph structure:

First, we perform initial node grouping based on node attributes, labels, and related information. Then, according to these initial groups, we collect the first-round intra-community clustering degree vectors (out-degree vectors), and use them together with graph structural and node similarity information to construct an initial directed graph. After obtaining the initial graph, we apply graph embedding to extract its low-dimensional representations. Next, during the second round of information collection, each user uploads their updated community degree vectors—now including both out-degree and in-degree information—based on the community structure of the initial graph. Finally, we utilize the low-noise information gathered in the second round, together with the initial graph embeddings, to perform graph structure enhancement: weakly correlated edges in the initial graph are pruned, while strongly correlated edges are reinforced or added based on the embedding similarity, resulting in an updated and higher-quality final synthetic directed graph.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

We propose a directed graph generation method under Local Differential Privacy (LDP) that preserves user privacy while ensuring that the generated synthetic directed graph maintains high data utility.

We integrate ideas from graph structure learning, performing node partitioning based on node attributes and constructing the initial graph using the first-round community degree vectors. Then, we apply structural enhancement using the second-round community degree vectors combined with graph embeddings to mitigate noise effects and further improve the data utility of the final synthetic graph.

We conduct extensive experiments on four real-world datasets, including three directed graph datasets and one directed version of an originally undirected dataset. The experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness and utility of the proposed approach.

2. Related Work

At present, a large number of graph synthesis and publishing methods based on Local Differential Privacy (LDP) have attracted widespread attention. Privacy-preserving graph learning in centralized environments has been extensively studied [

6,

7,

8,

9]. These methods typically start with the observation that similar graphs share structural properties and aim to generate new graphs from similar distributions. Representative approaches employ Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) or their variants to learn from node features extracted from the graph. However, such methods rely on a centralized server for data collection and training, making them unsuitable for decentralized network settings. In decentralized environments, most existing privacy-preserving graph methods focus on edge-level protection. The most fundamental approach is the Randomized Response (RR) mechanism [

10], in which each user randomly flips bits in their local adjacency view, and the system aggregates these perturbed local views into a global graph. However, the RR-based local view is high-dimensional—its dimension is nearly proportional to the number of users—thus inevitably introducing substantial noise, which becomes even more severe in the case of directed graphs. Another feasible approach collects only low-dimensional graph statistics [

11], such as node in-degree and out-degree, and then synthesizes graphs using generative models like BTER or Chung–Lu. While this method reduces the impact of noise, it tends to produce graphs with overly random neighbor relationships for in- and out-degrees, resulting in a significant deviation from the original data and lower data utility.

For graph generation in decentralized settings, Qin et al. [

2] analyzed the limitations of initial graph generation methods in terms of noise and proposed LDPGEN, a method based on node grouping and the computation of grouped degree vectors, marking an early exploration of graph synthesis under LDP. However, this approach still introduces a large number of spurious edges, which can distort the graph’s structural properties. Wei et al. [

12] separately processed node attribute information and degree information, estimating unbiased and joint distributions to reduce noise influence, and proposed the ASGLDP algorithm based on consistency principles, which generates more reasonable graph structures. Nonetheless, its sampling process may lose fine-grained node-level details. Ye et al. [

13] identified adjacency bit vectors and node degree vectors as important metrics that can effectively guide subsequent graph synthesis, though this approach also suffers from significant noise, affecting the quality of the generated graphs. Hu et al. proposed WTLDP, an improved method for undirected weighted graph synthesis under LDP, by applying low-noise perturbations and optimizing community partitioning—representing an initial exploration into the domain of LDP-based weighted attributed graphs. Regarding graph analysis and downstream tasks under Local Differential Privacy (LDP), clustering is a key operation for analyzing and understanding the complex structure of graph data. Zhang et al. [

14] explored clustering under LDP by classifying nodes based on partition thresholds and iteratively refining the clusters for improved accuracy. However, their method performs poorly when node degree vector distributions are relatively uniform. Fu et al. [

15] extended clustering to directed graphs, proposing the concept of viewing a directed graph as a star-shaped graph and incorporating 2-hop neighbor information for clustering. While effective, this approach introduces substantial inter-node computations, leading to high time complexity. Guo et al. [

16] employed an extreme-value optimization strategy for community detection and social relationship generation, achieving promising results in recommendation systems. Zhang et al. [

4] applied homomorphic sensing to preprocess node information and construct an initial graph, then introduced an average degree vector–based structural enhancement during GNN training to balance the trade-off between noise and structural fidelity—offering valuable insights for applying synthetic graphs to downstream tasks.

In graph synthesis, Yuan’s method [

17] neglected the impact of noise on the final synthetic graph, resulting in low overall data utility. Hou et al. [

14] improved these approaches through graph structure learning (GSL), which models the relationship between node attributes and graph topology in an end-to-end manner. By learning low-noise structural representations and synthesizing graphs based on them [

4], this approach reconstructs realistic decentralized graph data with higher data utility.

It is well known that directly processing typical network structures can lead to extremely large data volumes and high computational complexity. To address this, Cui et al. [

18] introduced node embedding, which encodes network structures into continuous, low-dimensional vector representations that effectively preserve local network information. The Word2Vec algorithm (Mikolov et al., 2013) [

19] employs a skip-gram model to convert textual words into low-dimensional embeddings, ensuring that similar words have similar vector representations. DeepWalk (Perozzi et al., 2014) [

20] combines random walks with the skip-gram model to learn node representations in networks. Node2Vec (Grover and Leskovec, 2016) [

21] further optimizes random walks by maximizing the likelihood of node co-occurrence, producing higher-quality and more informative embeddings than DeepWalk [

22]. Regarding the integration of local differential privacy with other techniques, federated learning (FL) was once considered secure. Miao [

23] proposes a compressed privacy-preserving federated learning scheme (CAFL) based on a deep neural network architecture, which uses compressive sensing and adaptive local differential privacy to improve model accuracy under strong noise. Xie [

24] presents an efficient and secure federated learning scheme (ESFL), which leverages adaptive LDP and compressive sensing to resist backdoor attacks and addresses the limitations of traditional LDP-based FL schemes. Zhang [

25] proposed MENTOR, a hybrid model-based recommendation method that integrates matrix factorization within the LDP framework, demonstrating its great effectiveness in balancing privacy and practicality in recommendation systems. Feng [

26] proposes for the first time a recurrent neural network based on differential privacy tensors (DPTRNN), ensuring data privacy while keeping accuracy loss within an acceptable range.

In summary, existing research has primarily focused on undirected and weighted graphs, with relatively limited exploration of directed graph data [

27,

28,

29]. For undirected graphs, the analysis typically involves binary relationships (the presence or absence of edges). In contrast, directed graphs require not only identifying edge existence but also handling edge directionality, making methods designed for undirected graphs unsuitable for directed data. Furthermore, it is essential to account for noise effects when processing collected data. In our work, we leverage graph structural information and graph embeddings to effectively synthesize directed graph data and address these existing challenges.

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Problem Statement

Given a directed graph dataset

, where

denotes the set of nodes and

represents the set of directed edges (e.g., “follow” or “transaction” relationships),

represents the overall graph data. For each user (node)

, the out-degree adjacency matrix row can be expressed as a vector

. Formally, the adjacency matrix of the directed graph is defined as:

Under the Local Differential Privacy (LDP) setting, we assume that each user only has access to their own outgoing view (which can be considered as a star-shaped subgraph consisting of their outgoing edges). This corresponds to a single row of the out-degree adjacency matrix, representing the user’s connections to others.

From the server’s perspective, the goal is to collect information from all users without violating privacy, aggregate the perturbed data, and synthesize a global graph structure that closely approximates real-world relationships among users (such as social links or transaction records). Third-party entities, such as network operators, can then utilize this synthesized global graph for various downstream tasks, including community detection and social recommendation.

3.2. Local Differential Privacy

Unlike traditional Differential Privacy (DP), Local Differential Privacy (LDP) assumes that no centralized server can be trusted. To obtain personalized services while preserving privacy, users must perturb their own data locally before uploading it. The server then processes the perturbed data—performing tasks such as denoising, data reconstruction, or synthetic data generation. The formal definition of Local Differential Privacy is as follows [

4]:

, where

denotes the randomizing (perturbation) mechanism,

and

are any two possible user inputs, and the output is the perturbed value. Here,

is the privacy budget,

is the domain of possible user inputs, and

represents any measurable subset of the output space. The term

denotes the probability that the mechanism’s output lies within set

given input

.

In addition, let f(x) denote a numeric statistic computed on user data (e.g., the community out-degree of a node). The global sensitivity of f is defined as:

For community-level degree vectors, changing a single user’s true data can affect each component by at most 1, thus for each coordinate. From this definition, it is clear that the privacy budget controls the level of randomness (or “blurring”) applied to the input data:

When is small, the output distributions corresponding to different inputs are more similar, providing stronger privacy protection but potentially reducing data utility due to higher noise.

Conversely, when is large, the perturbation is weaker, improving data utility but weakening privacy protection.

3.3. Graph Structure Learning

Graph structure learning aims to infer or optimize the structure of a graph from data, making it more suitable for downstream tasks. The community degree vector serves as a key representation in this process—it reflects the node structure based on community partitioning. For directed graphs, once the nodes are divided into different communities, the out-degree community vector and in-degree community vector, respectively, represent the total number of directed edges from one community to others and from other communities to that community. The length of these vectors depends on the number of communities.

In previous methods, nodes were often grouped randomly, resulting in indistinct community structures and poor data utility. Direct edge generation under such random groupings is highly sensitive to noise, which degrades the quality of the synthesized graph. In our work, inspired by the idea that preserving structural symmetry helps maintain balanced and coherent graph topology, we adopt an iterative refinement strategy from graph structure learning to better preserve both local and global structural patterns. By incorporating graph embeddings and reducing spurious asymmetric edges introduced in the second-round noisy community degree vectors, we update the initial graph synthesized from the first-round community degree vectors. This refinement effectively mitigates the impact of noise and produces a more reliable synthetic graph. We formally define this structure learning process as follows:

where

is the initial graph structure,

is the learned (optimized) graph structure,

denotes node features,

is the reconstruction or embedding loss,

is a balancing coefficient, and

is the structural consistency regularization term.

3.4. Edge Local Differential Privacy

Local Differential Privacy (LDP) can be categorized into two types: Node-level LDP, which protects the privacy of node attributes, and Edge-level LDP (Edge-LDP), which focuses on protecting the privacy of edge information. In this paper, we primarily focus on Edge-LDP.

Definition (Edge Local Differential Privacy): A randomized mechanism satisfies Edge-LDP if, for any two graphs G1 and G2 that differ by exactly one edge, and for any possible output, the following holds: Here, denotes that the two graphs differ by one directed edge, is the perturbation mechanism, is the privacy budget, and represents the output space of all possible perturbed graphs.

4. Solution

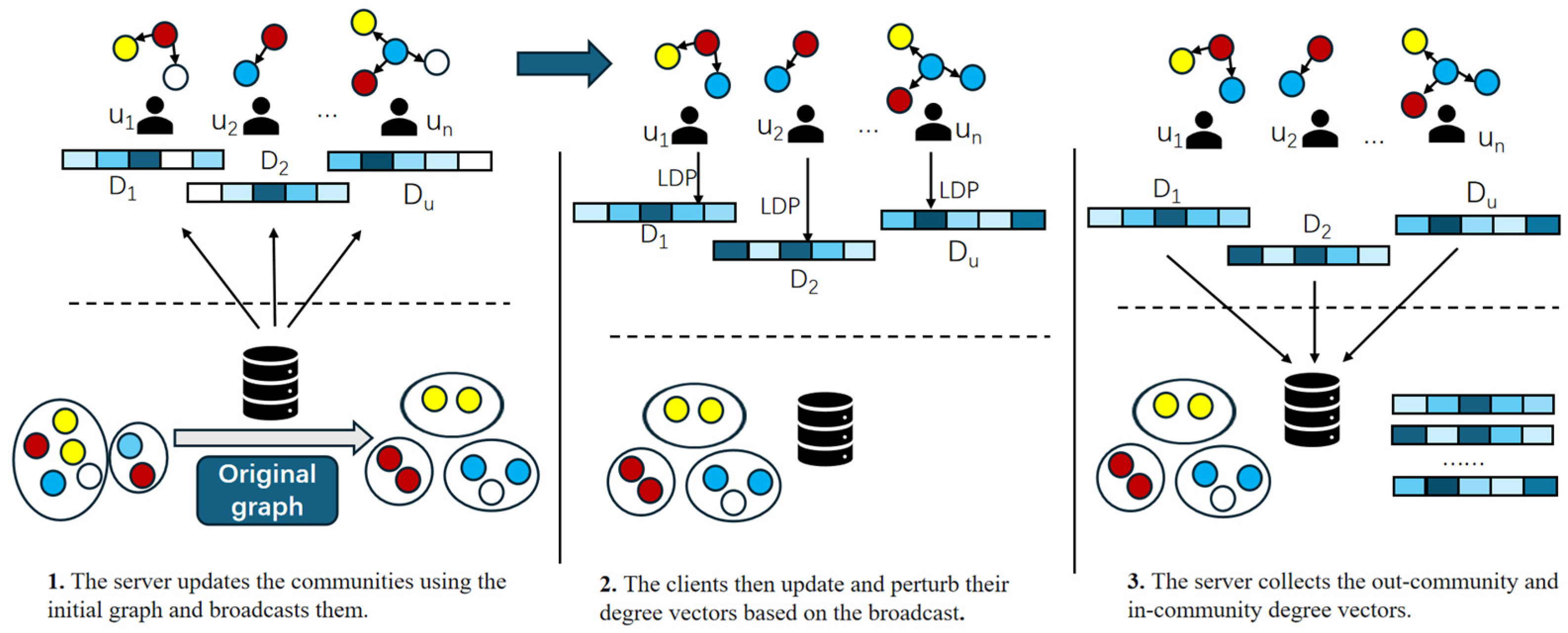

As shown in

Figure 1, our directed graph synthesis framework consists of three main stages: Stage 1: We first collect node attributes and perform community-based node classification. Stage 2: On the client side, each user uploads a community out-degree vector for their node based on the initial community partition (broadcast by the server after classification). The server then computes node similarities, aggregates the collected community degree vectors, and generates edges both within and between communities. Next, a graph embedding is performed to obtain low-dimensional node representations, which are used to update the community partition. Stage 3: Users again upload community degree vectors based on the updated community partition (after the server’s second broadcast). At this point, each node’s vector contains both community out-degree and in-degree information.

We then combine these vectors with the previously obtained graph embedding structure to perform structural enhancement—removing weak, low-correlation edges from the initial graph and adding new strong edges that satisfy high-similarity conditions. This process produces the final synthesized directed graph, which demonstrates stronger connectivity and higher data utility—more closely resembling the original graph. The overall experimental framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Regarding node information, we note that in user-oriented applications such as social media, each user’s private data typically includes items such as contacts, follow lists, or transaction records, which the server cannot freely access. However, inherent user attributes—such as labels, interests, or activity histories—are usually voluntarily provided or selected during app usage, and thus are accessible to the server without violating user privacy.

In our approach, DGG-LDP first partitions nodes into initial communities based on non-private attributes. Then, using the Initial Graph Generation (IGG-LDP) algorithm, we compute node similarities and construct the initial graph.

Finally, by combining the initial graph embedding with the updated community out-degree and in-degree vectors, the Final Graph Generation (FGG-LDP) algorithm synthesizes the final directed graph. The resulting synthetic graph and node embeddings can subsequently be applied to downstream tasks such as social recommendation and link prediction. In

Section 4,

Section 4.1 introduces the initial community partition and the collection of community degree vectors;

Section 4.2 discusses the initial graph generation and presents the graph embedding process;

Section 4.3 explains the structural enhancement mechanism and the principles for updating edges;

All privacy proofs for the noise-added mechanisms are provided in

Section 4.4.

4.1. Community Partitioning and Degree Vector Collection

In conventional approaches, researchers often represent each node’s adjacency list in a decentralized network as a binary view. When users upload their edge information, they typically employ a randomized perturbation mechanism, such as applying randomized response to each bit of their adjacency list. However, this approach introduces substantial noise. The community degree vector proposed in LDPGEN [

2] effectively alleviates this issue. Instead of reporting individual edges, each node reports a community-based degree vector, which records the number of connections between the node and each community. This design not only captures the encoding information of communities and nodes but also significantly reduces noise.

It is worth noting that when using community-based structures, the number of communities must be predefined. The method for determining the optimal group number proposed in the LDPGEN [

2] paper (for undirected graphs) remains applicable here. We integrate this method with the node classification results produced by our classifier and evaluate multiple trials to determine the optimal community partition size.

To perform the initial community partition, we follow the approach in [

4] and pretrain a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) classifier that satisfies edge-local differential privacy (Edge-LDP). This MLP is trained on non-private node attributes and labels, and assigns each node to a corresponding cluster based on its label information. The server then broadcasts the community assignments to all users. Once the initial community partition is established, each user uploads their community out-degree vector, computed based on their assigned community. To ensure Edge-LDP protection, each vector is perturbed with noise before uploading. The server collects these noisy community degree vectors for use in subsequent stages of graph synthesis.

4.2. Initial Graph Generation

In this section, our main goal is to generate an initial graph using the community structure obtained from the MLP classifier together with the collected noisy community out-degree vectors, serving as a foundation for subsequent graph enhancement.

Traditional graph generation models—such as the Chung–Lu model—create edges between nodes based on random probabilities. However, generating edges purely at random introduces many false or spurious edges, which degrade the utility of the initial graph. To mitigate this, we reuse node label information and compute pairwise node similarities, adding edges only between nodes with similarity above a given threshold.

The similarity metric is defined as:

where

and

are two nodes in the graph,

denotes the set of neighbors directly connected to

, and

denotes the neighbor set of

. For directed graphs, edges can be outgoing or incoming, leading to distinct effects. To simplify computation and conserve the privacy budget, we adopt the out-degree star view described earlier, treating each edge as an outgoing edge. We then apply a similarity-weighted variant of the Chung–Lu model to generate the initial directed graph.

The initial graph generation process is shown in Algorithm 1.The generated initial graph already exhibits basic structural utility, reflecting underlying relationships among nodes to some extent. Subsequently, we perform graph embedding on this initial structure, using random walks to obtain directed walk sequences for each node. From these sequences, we identify frequently co-occurring nodes as candidate connections, which will later be used to enhance the graph structure in the final synthesis stage.

| Algorithm 1. IGG-LDP (Initial Graph Generation) |

Input:- ●

Node feature vector set: - ●

: - ●

Noisy community out-degree vectors uploaded by user (expected connections to each community) - ●

Weighted averaging parameter

Output:- ●

Initial directed graph

Procedure:- 1.

Initialize an empty directed graph . - 2.

Compute the node similarity matrix , where - 3.

Construct a node constraint matrix:

- (1)

For each node pair ,

- i.

set .

- 4.

Compute the hybrid matrix . - 5.

For each node :

- (1)

Retrieve the noisy vector uploaded by user , where each dimension has been independently perturbed with Laplace noise - (2)

For each community :

- i.

If : continue - ii.

Define the candidate set - iii.

Compute scores for each candidate . - iv.

Select the top nodes with the highest scores and add edges .

- 6.

Return the constructed initial directed graph .

|

Moreover, to obtain low-dimensional structural representations of the intermediate graph, we employ Directed Node2Vec, consistent with the asymmetric adjacency and random-walk transition rules of directed graphs. In our implementation, the bias parameters are set to mildly encourage breadth-first exploration and preserve local community information. Since Node2Vec relies on stochastic random walks, the embeddings exhibit mild variance across different runs. However, in the DGG-LDP pipeline this variance has a limited effect on the overall stability for two reasons: embeddings are used only in the refinement stage, after an initial structure has already been constructed using community-based degree vectors; the refinement is regulated by the hyperparameter α, which restricts the pro-portion of edges that may be replaced. Consequently, the stability of the final graph depends more strongly on the balancing coefficient α than on small fluctuations in the embedding space.

4.3. Final Graph Generation

In

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2, we collected noisy community-based out-degree vectors and generated an initial graph structure based on the initial community partition. However, this preliminary structure remains imprecise. To better approximate the true edge relationships in the original graph, we update the initial graph in this stage.

After executing the IGG-LDP algorithm, the server refines the original coarse community structure based on the initial graph and broadcasts the updated community partition to all users. Each user then updates their out-degree and in-degree adjacency lists according to the new community assignment. During this second perturbation round, users again upload their community-based degree vectors, but this time, the vectors are based on the refined community structure (which more accurately reflects the true data). The privacy budget allocated in this round is larger than in the first round, and is evenly divided between the out-degree and in-degree community degree vectors to balance privacy and utility.

After the server receives the outgoing and incoming community degree vectors from all users as it shows in

Figure 2, it applies a symmetry-based refinement procedure. For each node, the server examines its community-level out-degree and in-degree vectors: if both vectors indicate the presence of the same edge, the edge is classified as a strong edge. If an edge appears only in the community out-degree vector but not in the in-degree vector (or vice versa), it is considered a weak edge. Weak edges are then corrected by enforcing symmetry—i.e., replacing the missing direction with the corresponding strong counterpart.

Subsequently, these refined edges are integrated with the previously obtained graph embeddings to compute node-to-node similarity. Using the candidate neighbor sets preserved from the embedding stage, the algorithm replaces weak edges with stronger and more structurally meaningful connections. Specifically, based on the node’s embedding-based top candidate set:

where

is the set of directed random walk sequences starting from node

is the candidate node set,

is the candidate set size.

Weak edges (with similarity below a certain threshold) are iteratively replaced with stronger edges connecting to high-similarity candidates. The process repeats until all edges with similarity below the threshold are replaced.

Through the FGG-LDP algorithm shown in Algorithm 2, weak or noisy connections in the initial graph are progressively replaced with high-similarity, community-consistent edges, improving structural fidelity. As a result, the final synthesized graph achieves higher utility, better preserving the topological and community structure of the original directed network while maintaining Edge-LDP guarantees.

| Algorithm 2. FGG-LDP (Final Graph Generation) |

Input:- ●

Initial graph - ●

Node attribute matrix (e.g., community one-hot vectors) - ●

Perturbed clustering degree vectors - ●

Control parameters: - ●

Candidate set size , minimum replacement similarity , iteration number .

Output:- ●

Final structurally enhanced graph .

Procedure:- 1.

Initialize , let be the node set and . - 2.

For each iteration : - (1)

Perform graph embedding on to obtain the embedding matrix . - (2)

Construct node feature vectors by concatenating embedding, attributes, and degree vectors: - (3)

Compute the node similarity matrix: - (4)

Initialize a new empty graph G’ and add all nodes . - (5)

For each node :

- i.

Retrieve its outgoing neighbor set . - ii.

Sort all by , and retain the top edges as strong edges . - iii.

Add strong edges to (G’). - iv.

Construct a candidate set - v.

Select the top most similar nodes satisfying , and add edge with probability .

- (6)

Update .

- 3.

Return the final enhanced graph .

|

4.4. Illustrative Example of DGG-LDP

To highlight the core and innovations of DGG-LDP, we provide a small illustrative example consisting of six nodes partitioned into two communities:

Community A: {1, 2, 3} (blue).

Community B: {4, 5, 6} (red).

The original directed graph contains intra-community dense links, sparse cross-community links, and asymmetric directions. There are two communities, so the length of the community degree vector is now two. In the first stage, users upload only their community out-degree vectors under local differential privacy (the vectors in the image are for demonstration purposes only and have not been noised). Based on these noisy vectors and node similarity, the server constructs an initial directed graph. As shown in

Figure 3, the initial graph already recovers part of the true community structure, but certain edges are incorrect due to LDP noise (e.g., the direction between nodes 2 and 3 is reversed, and the edge 5→6 is missing).

Next, the server performs directed graph embedding, which preserves asymmetric transition statistics and places nodes from the same community into coherent clusters in embedding space.

In the second stage, users upload lower-noise community out-degree and in-degree vectors, enabling the server to refine the structure. Using the refinement strategy, the algorithm retains α = 0.8 of strong existing edges and selectively adds high-similarity candidate edges with probability β = 0.2. This process corrects incorrect directions and restores missing edges. The final synthetic directed graph aligns closely with the original structure.

This example demonstrates three key properties of DGG-LDP:

Directional preservation under LDP: community-level vectors allow recovery of directed patterns without exposing node-level degrees.

Two-stage LDP significantly improves fidelity: the refinement round reduces noise-induced distortions.

FGG is essential: it corrects orientation errors and recovers missing structure that the initial LDP stage cannot resolve.

4.5. Privacy Analysis

In this section, we demonstrate that DGG-LDP satisfies Edge Local Differential Privacy (Edge-LDP). Recall the definition of Edge-LDP: a randomized algorithm

satisfies

if and only if for any two input graphs

and

differing by exactly one edge, and for any output

, we have:

Theorem 1. The star-graph-based community out-degree vector collection mechanism satisfies local differential privacy. In this mechanism, each node computes its connections to each community and adds Laplace noise:where is the number of edges from node to community (this stage only considers out-degree). The sensitivity is 1, since adding or removing a single edge can change at most one community count by 1. Proof. Let graphs

and

differ by only one edge. This affects the vector of some node

:

and

, For any output vector

:

Using the Laplace mechanism’s probability density function:

Thus, the perturbed community out-degree vector uploaded by each node satisfies . During initial graph construction, these vectors are used to generate edges by the server. Since edge generation is performed server-side without additional access to raw user data, this stage preserves . □

Theorem 2. The two-stage community out-degree and in-degree vector collection mechanism satisfies local differential privacy.

In the second stage, users upload perturbed out-degree and in-degree vectors:

The sensitivity per dimension remains 1. The perturbation is applied independently to each dimension, with vector length now 2C.

Proof. Analogous to Theorem 1: a single edge affects at most one dimension (out-degree or in-degree for a community), and Laplace noise is added independently. Therefore, also satisfies . Consequently, in the structure enhancement stage, uploading perturbed out-degree/in-degree vectors also satisfied . □

The final graph generation only performs edge replacement or addition based on these vectors, without additional privacy cost.

Theorem 3. The entire Directed Graph Generation process satisfies .

According to the Sequential Composition Theorem [

26] in LDP: if mechanisms

) satisfy

respectively, then their combined mechanism

satisfied

.

Thus, the overall Directed Graph Generation algorithm satisfies: . Hence, the proposed algorithm ensures edge-level local differential privacy throughout the graph synthesis process.

4.6. Hyperparameter Settings and Rationale

The proposed DGG-LDP framework contains several hyperparameters in both the initial graph construction stage and the refinement stage. To ensure reproducibility and clarify their functional roles, this subsection provides a formal definition, theoretical justification, and principled selection rules for the fusion coefficient α, the replacement probability β, and the candidate size .

- (1)

Fusion coefficient . In the FGG-LDP update, α controls the proportion of existing outgoing edges retained for each node. A larger α encourages conservative updates that preserve the original structural backbone, while a smaller α allows more edge replacement and increases the level of exploration.

- (2)

Replacement threshold For each high-similarity candidate edge in the top-K set, the algorithm adds the edge with probability β. Larger values increase the expected number of new edges and may improve recall, whereas smaller values favor precision and mitigate noise amplification.

- (3)

Candidate size . For each node, only the nodes with the highest similarity scores are considered as potential replacements of weak edges. The value of determines the size of the local search space, significantly affecting both computational complexity and refinement behavior.

5. Experimental Evaluation

5.1. Datasets and Parameters Configuration

Advogato is an online community of open-source software developers, representing a trust network among users. The edge direction indicates that node i trusts node j, and the edge weight represents one of four increasing levels of declared trust from i to j: Observer (0.4), Apprentice (0.6), Journeyer (0.8), and Master (1.0). It consists of 6542 nodes and 51,127 directed edges. In our study, we ignore edge weights and only process directed edges.

Soc-sign-bitcoinalpha represents a “who-trusts-whom” network among users transacting with Bitcoin on the Bitcoin Alpha platform. The edge direction indicates that node i trusts node j, and members rate others on a scale from −10 (completely distrust) to +10 (completely trust). The dataset contains 3783 nodes and 24,186 directed edges. On-chain transaction graphs are sometimes public at the level of pseudonymous addresses, but linking addresses to real-world identities, off-chain metadata, or user behavioral attributes remains sensitive. In our practice the local views are sensitive.

Soc-sign-bitcointrust is a trust network from the Bitcoin OTC platform, similar to the Alpha dataset. The edge direction indicates node i trusts node j, with trust scores ranging from −10 to +10. It contains 5881 nodes and 35,592 directed edges.

Facebook-M2 comes from the Facebook-organizations (2013) dataset, which consists of six friendship networks among users employed at six target companies, with varying company sizes. We use the M2 network, which originally is an undirected graph of 3862 nodes and 87,364 edges [

30]. For our study, we treat each edge as directed from the source node to the target node, converting the dataset randomly into a directed graph.

In all experiments, the value represents the total privacy budget available to each user. This budget is allocated proportionally to the two phases of our framework: 40% of the total budget is allocated to the first phase, and the remaining 60% is allocated to the second phase. In the second phase, the budget is further evenly distributed between the perturbed out-degree and in-degree vectors, ensuring symmetric protection of information in both directions. The hyperparameters α and β were set to 0.8 and 0.2, respectively. This allocation scheme remains consistent across all datasets and experimental settings.

5.2. Baseline Methods

To demonstrate and compare the performance of our proposed method, we use three partially adapted classical algorithms as baselines:

LDPGEN-D: Proposed by Qin et al. [

2], LDPGEN initially partitions communities, then refines them using K-means, collects community degree vectors, and generates the graph structure using the Chung-Lu model under edge-level local differential privacy. The original LDPGEN is designed for undirected graphs and is not fully applicable to directed graphs. We refine its degree vector collection by splitting the privacy budget evenly between community out-degree and community in-degree vectors, using this adapted version as Baseline 1. Specifically, we adapt the LDPGEN pipeline by separating collected grouped degree vectors into out-directed and in-directed components. During synthesis, the allocated group-level outgoing counts for each source node are distributed to candidate target nodes within each destination group according to estimated in-degree weights. Formally, the per-edge probability can be written as:

Which reduces to uniform assignment if no further per-node in-degree information is available. Laplace perturbation is applied independently to each directed group-count dimension, preserving Edge-LDP at the directed-vector level.

ASGLDP-D: Proposed by Wei et al. [

12], this framework collects and generates attribute-based social graphs under LDP. Node attributes and degrees are perturbed and uploaded; unbiased and joint distributions of attributes are computed. The method then assigns degrees and attribute lists to nodes and generates an attribute graph using the AGM model. Finally, the graph is adjusted based on structural, attribute, and community consistency. Originally designed for undirected graphs, we adapt it to directed graphs by separating degree vectors into out-degree and in-degree, perturbing each with an equal privacy budget. This serves as Baseline 2. Specifically, the attribute-aware LDP generator adapts to the directed setting by modeling attribute out-degree and in-degree relationships separately and sampling directed edges based on source-target joint bias:

where

represents the direction-aware similarity term. This structure preserves attribute degree relevance while maintaining edge direction; Laplace noise is applied to the directed degree components consistent with Edge-LDP.

HAGLDP-D: Proposed by Zhang et al. [

4], this method is a structure-learning-based LDP graph learning approach for training GNNs under local differential privacy. It initializes with a homomorphically aware graph structure to reduce noise, assigns similarity scores to nodes, links edges based on graph homogeneity, and then enhances the graph using average degree vectors combined with neighbors’ degree vectors for GNN training in semi-supervised tasks. Originally for undirected graphs, we adapt it for directed graphs by separately collecting community out-degree and community in-degree vectors under the same privacy budget, without iterative GNN training. We combine homomorphically aware graph initialization with average degree vector estimation for directed graph generation, using this as Baseline 3. Specifically, to convert HAGLDP to a directed setting, we split the degree-related statistics into out-degree and in-degree components and replace the undirected neighborhood metric with direction-aware similarity. Specifically, the link probabilities following the Chung-Lu sampling style are replaced with:

This preserves the expected out-degree and in-degree. Neighborhood similarity is calculated from the directed neighbor set (e.g., ) by weighting the sender→receiver and receiver→sender overlap. These adjustments take into account the directionality of edges while maintaining the first-order statistical properties of the original HAGLDP.

5.3. Evaluation Metrics

For evaluating the data utility of the synthetic graphs, we consider two main aspects:

Experiments are conducted on each dataset under different privacy budgets. Graph Statistics: We evaluate graph statistics using the average clustering coefficient and global clustering coefficient.

Average Clustering Coefficient

measures the probability that a node’s neighbors form closed triangles, reflecting the general connectivity of the graph. It is defined as:

where the local clustering coefficient

is:

Here, is the number of edges among the neighbors of node (v) (triangle count), is the degree of node (number of neighbors), and is the number of nodes considered.

Directed Global Clustering Coefficient

adapts the global clustering metric for directed graphs, it considers the symmetry and asymmetry of edges in the directed graph and measures the probability that a node’s neighbors form a closed triangle, including one-way and two-way edges:

A is defined as a center node connected to two neighbors (via in-, out-, or mixed edges); a closed triplet has a third edge forming a closed loop among the three nodes.

Directed Average Clustering Coefficient: Fagiolo [

31] extended local clustering to directed graphs by considering all possible edge types (single- and double-directed edges), adjusting the denominator from the undirected version and removing double-counted edges:

Here, is the number of directed triangles involving node , is the total degree (in-degree + out-degree), and denotes the number of bidirectional edges connected to ( v and ).

Community Detection: We perform community detection on the synthetic directed graphs for soc-sign-bitcoinalpha, soc-sign-bitcointrust, and Facebook-M2. Since conventional community detection methods often ignore edge direction, we use a directed graph clustering method based on singular value decomposition (SVD) [

32]. The results are evaluated with the following metrics:

NMI (Normalized Mutual Information): A normalized version of Mutual Information (MI) that quickly measures the similarity between clustering results and true labels, scaled to [0, 1]. Higher values indicate more similarity [

33].

AMI (Adjusted Mutual Information): Adjusted version of MI that accounts for randomness, measuring shared information between two clusters. Its range is [0, 1], with higher values indicating more similar clustering [

34].

ARI (Adjusted Rand Index): Adjusted version of the Rand Index, accounting for random assignment, ranging from [−1, 1]. It measures the similarity between two clusters (predicted vs. true labels), with higher values indicating more similar underlying cluster structures and higher synthetic graph accuracy [

35].

5.4. Ablation Study

In our study, we performed initial community partitioning, degree vector uploads, initial graph generation, followed by a second round of degree vector uploads and graph updates.

For the ablation experiment, we simplify the algorithm by taking the initial graph after a basic community partition and generation, removing subsequent steps such as graph embedding and structural enhancement. This allows us to observe the effect of omitting graph embedding and structure-based updates on the synthetic initial graph, and to quantify the contribution of the second-round degree vector collection and graph structure enhancement to the final generated graph.

5.5. Experimental Results

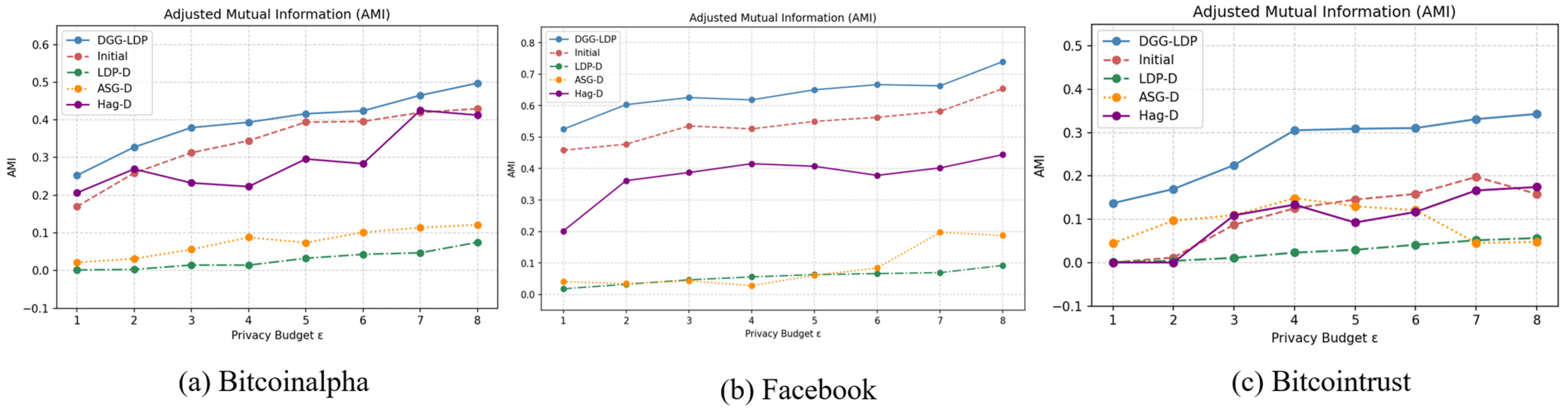

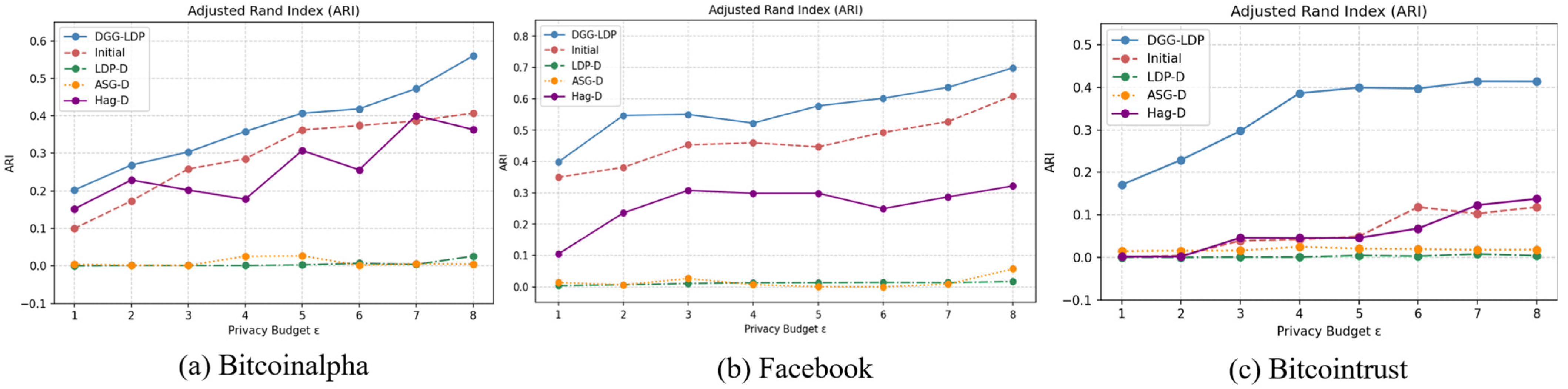

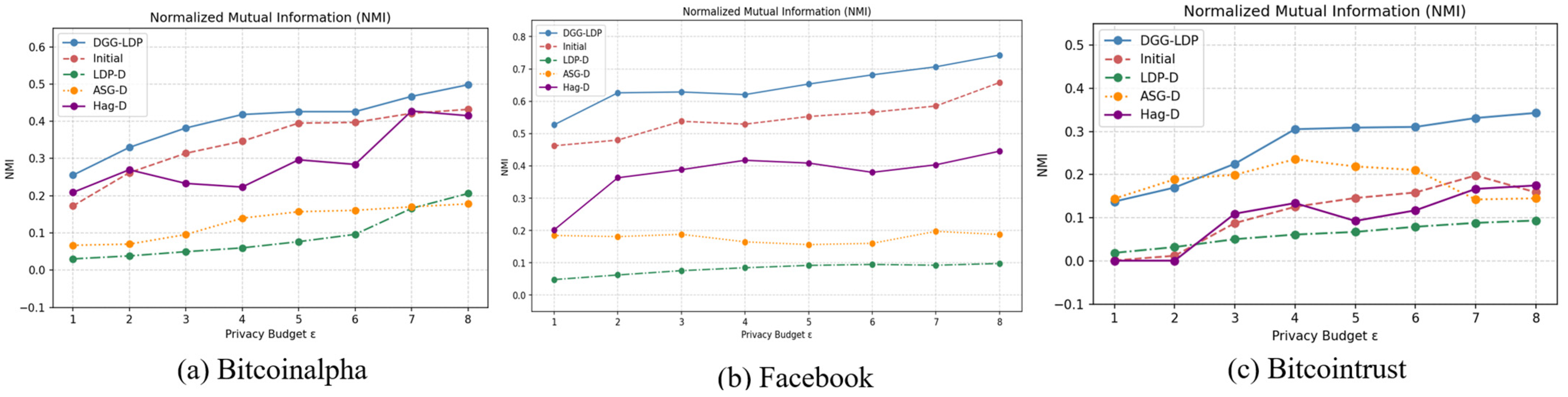

In this section, we report the experimental results of the community detection phase based on the aforementioned evaluation metrics. As shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, as the privacy budget increases, the community partitions obtained from the final synthetic directed graph become more consistent with the ground-truth community structure of the original graph. This is because a larger privacy budget allows the algorithm to preserve community out-degree and in-degree vectors with less noise perturbation, enabling DGG-LDP to more accurately reconstruct the original graph and generate synthetic graphs with higher data utility.

In comparative evaluations, the proposed method significantly outperforms the baseline approaches. Specifically, Baseline 1 and Baseline 2 fail to effectively leverage structural similarities between adjacent nodes, resulting in only coarse-grained community partitions. Meanwhile, Baseline 3 lacks refinement in community modeling, leading to limited ability to recover community information. In contrast, DGG-LDP better preserves the intrinsic community patterns in the graph through initial community partitioning and similarity computation.

A more detailed analysis from the metric perspective reveals the following observations. First, for all baseline methods, the AMI and NMI values are close, with NMI generally slightly higher than AMI. This is because AMI incorporates a normalization step that subtracts the expected mutual information due to random cluster assignments, thereby providing a debiased and more fair assessment. In comparison, our method effectively reduces structural errors in community partitioning by incorporating graph embeddings and node similarity measures, thus achieving better AMI and NMI performance across all three datasets with clear community structures.

Second, both AMI and NMI values are generally higher than those of ARI. This is attributed to the high sensitivity of ARI to partitioning errors: it strongly penalizes both splitting nodes from the same community into different clusters (fragmentation error) and merging nodes from different communities into the same cluster (merge error). By integrating similarity computation and graph structural embeddings, our approach better maintains node associations within and between communities, resulting in relatively higher ARI values across all three datasets, which reflects its more accurate recovery of community structures.

DGG-LDP, by combining similarity calculations with node graph embedding information, processes neighboring nodes more effectively, thereby better preserving the original graph’s community structure.

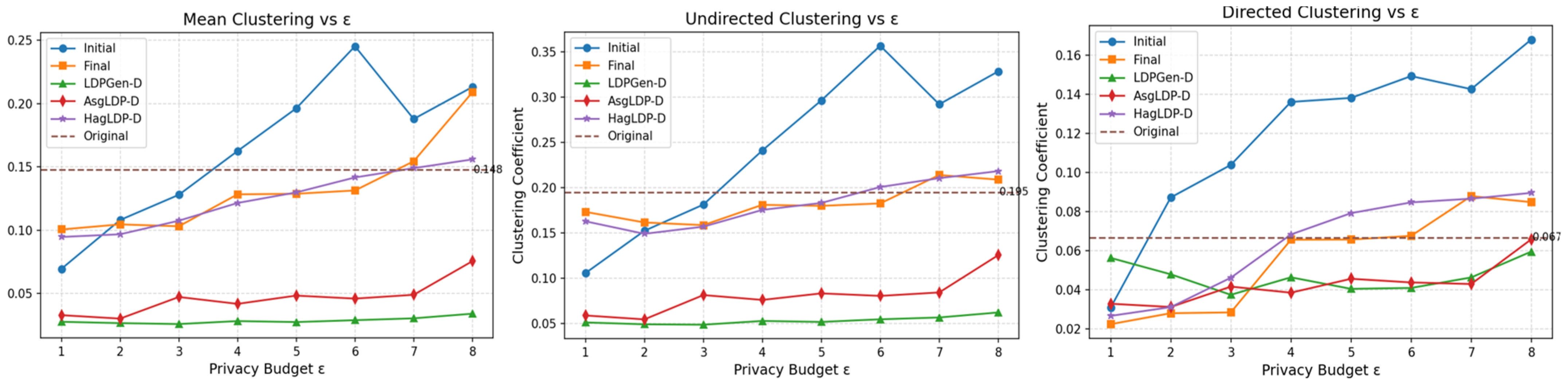

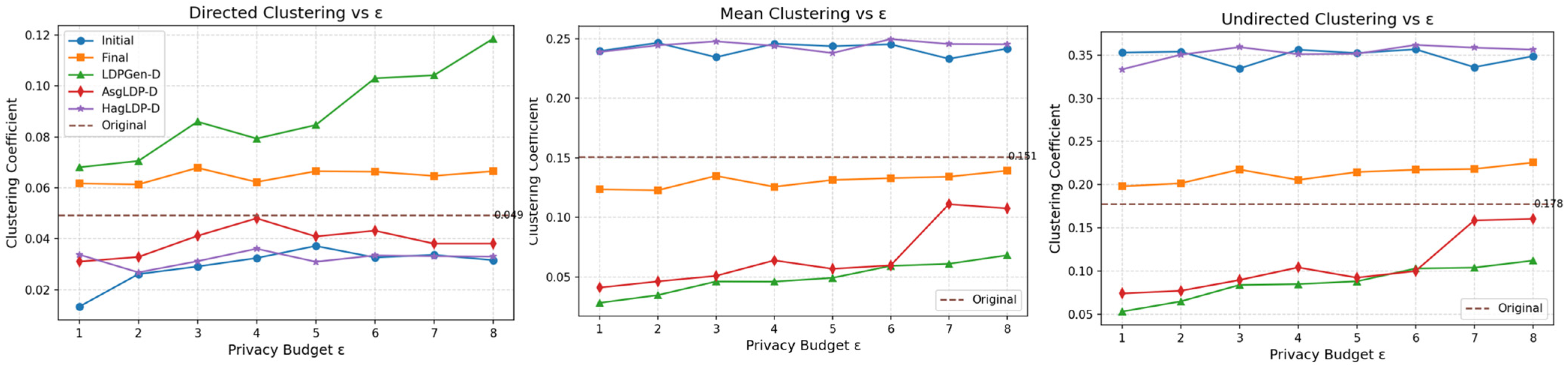

A In

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, the orange line represents the proposed DGG-LDP method. It can be observed that the synthetic graphs generated by the ablation study and other baseline methods exhibit significant deviations from the original graph in terms of structural metrics such as clustering coefficients. Specifically, in all three datasets, our method maintains the values of undirected clustering coefficient, directed clustering coefficient, and directed average clustering coefficient within a narrow range of fluctuation. By considering local clustering coefficients while preserving global average coefficients, it maintains the geometric symmetry of the graph. Unlike other approaches, the metrics do not monotonically increase with the privacy budget nor show large deviations. This indicates that during the graph synthesis process, DGG-LDP effectively reconstructs the topological characteristics of the original graph through similarity calculation and filtering mechanisms, combined with secondary graph structure learning and iterative updates, rather than merely relying on an increased privacy budget to enhance data utility.

In summary, Baseline 1 and Baseline 2 preserve certain graph structural features to some extent, but the community structure quality in their synthetic graphs is relatively poor. Baseline 3 performs better in restoring community structures, but falls short in maintaining graph topological properties. The proposed DGG-LDP method comprehensively incorporates multiple aspects of graph structural information, considered and utilizes the symmetry difference between directed graphs and undirected graphs, and achieving a better balance between privacy protection and graph data utility.

5.6. Statistical Evaluation, Variability Analysis, and Computational Complexity

5.6.1. Subsubsection

In this section, to assess the stability and robustness of the proposed DGG-LDP framework, we perform a statistical evaluation across 10 independent runs under a fixed privacy budget of ε = 4. Because the randomization mechanisms in our method—Laplace perturbation, directed Node2Vec sampling, and the stochastic edge-replacement rule—introduce inherent variability, reporting only single-run results would not be sufficient. Therefore, all metrics are presented in the form of mean ± standard deviation. In all experimental configurations, 40% of the total privacy budget was assigned to the first phase, while the remaining 60% was allocated to the second phase. The refinement procedure used fixed hyperparameters across all datasets, namely α = 0.8 and β = 0.2.

Table 1 summarizes the structural utility metrics, including AMI, ARI, and directed clustering coefficients. AC, DGC and DAC means Average Clustering Coefficient, Directed Global Clustering Coefficient and Directed Average Clustering Coefficient.

Most low standard deviations observed across all datasets indicate that the proposed refinement mechanism is stable, and the variability is well controlled by the balancing hyperparameter. The results confirm that the observed performance gains are not due to random fluctuations. Furthermore, in scenarios with highly sensitive node information—such as the Bitcoin-Trust dataset—the community structure becomes difficult to identify during the initial partitioning stage. The initial synthetic graph exhibits low utility (with an ARI of only 0.09). Nevertheless, through the subsequent structural enhancement phase, the generated directed graph becomes significantly closer to the original topology, improving the ARI to 0.32, and the structured data is also closer to the original graph. This outcome highlights the necessity and effectiveness of the second-stage refinement when dealing with complex directed networks.

5.6.2. Algorithm Limitations

Although DGG-LDP achieves strong structural utility on several real-world datasets, several important limitations should be noted:

Dependence on non-high private community information. The initial community partition in our pipeline relies on an MLP classifier trained on (non-private or weakly private) node attributes. In such cases (for example, certain configurations of the Bitcoin-Trust dataset), the quality of the initialization degrades and downstream refinement can only partially re-cover the structure, often yielding lower final utility

Limited applicability when mesoscopic structure is absent. DGG-LDP assumes the presence of meaningful mesoscopic community structure. If the underlying network lacks community structure (e.g., it is extremely sparse or nearly fully connected), community degree vectors become non-discriminative and lose efficacy.

Degradation under very strong privacy (very small ε). When the privacy budget is extremely small, the scale of Laplace perturbation grows so large that the injected noise may dominate the structural signal, and the synthetic graph may diverge substantially from the original topology.

Together, these limitations clarify the practical operating envelope of DGG-LDP and suggest concrete directions for future work in algorithmic robustness and scalability.

5.6.3. Computational Complexity

The computational cost of DGG-LDP is dominated by four components.

Directed graph embedding,

Similarity estimation among all nodes,

Initial Graph Generation,

The iterative structural refinement stage.

We summarize them in

Table 2, where n denotes the number of nodes, m denotes the number of edges, k is the top-K parameter used in the refinement stage, d denotes the embedding dimension, L and W are the random-walk length in Node2Vec and the number of walks per node, respectively.

While the proposed DGG-LDP framework provides substantial improvements in structural utility, its computational cost—particularly from graph embedding and all-pairs similarity computation—remains non-trivial, suggesting that future work could explore more scalable embedding and neighbor-search techniques.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a locally differentially private directed graph synthesis method, named DGG-LDP, which ensures edge-level local differential privacy for graph data. DGG-LDP is capable of generating graphs under low privacy budgets while preserving data utility.

The method integrates noisy degree-vector collection, community-aware initial graph construction, directed graph embedding, and a refinement stage that leverages low-noise structural signals. Experiments on three real-world directed datasets and one transformed directed dataset demonstrate that DGG-LDP can maintain meaningful structural patterns under moderate privacy budgets, effectively balancing privacy protection and utility.

In future work, we aim to focus on novel graph attributes, such as edge weights, combinations of weight and direction, and dynamic graph handling. The goal is to maintain high data utility while still protecting user privacy. Additionally, we plan to explore integration with machine learning tasks, enabling the synthetic graphs to support prediction, analysis, and other more complex downstream applications.