Research on the Follow-Up Braking Control of the Aircraft Engine-Off Taxi Towing System Under Complex Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

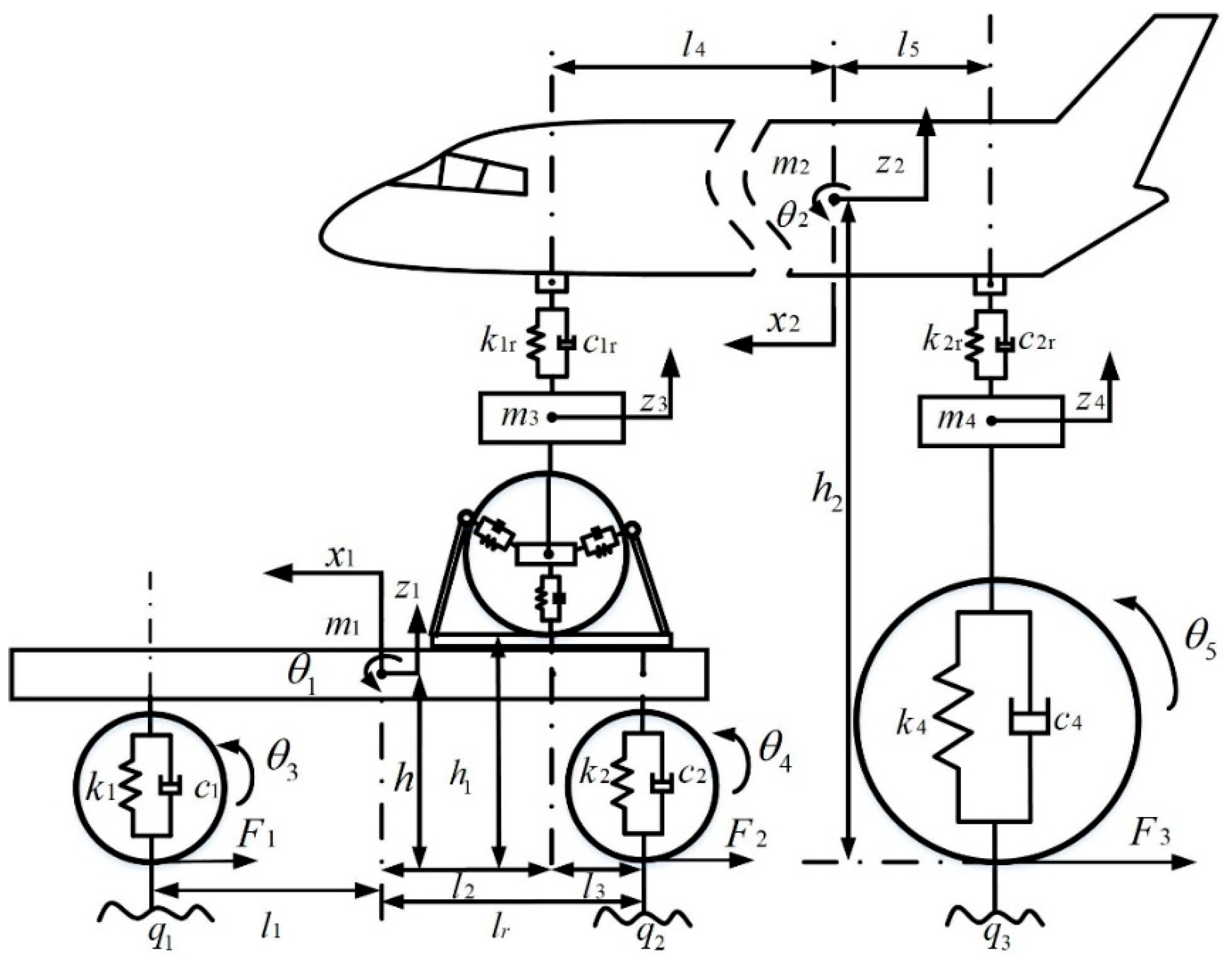

2. Symmetry-Based Dynamic Model of AEOTTS

2.1. Symmetry-Based Longitudinal Dynamic Modeling of the AEOTTS

- (1)

- The AEOTTS longitudinal dynamic equations

- (2)

- The wheel rotation dynamic equations

- (3)

- The total vertical load of each wheel

- (4)

- The AEOTTS Vertical Dynamics Equations

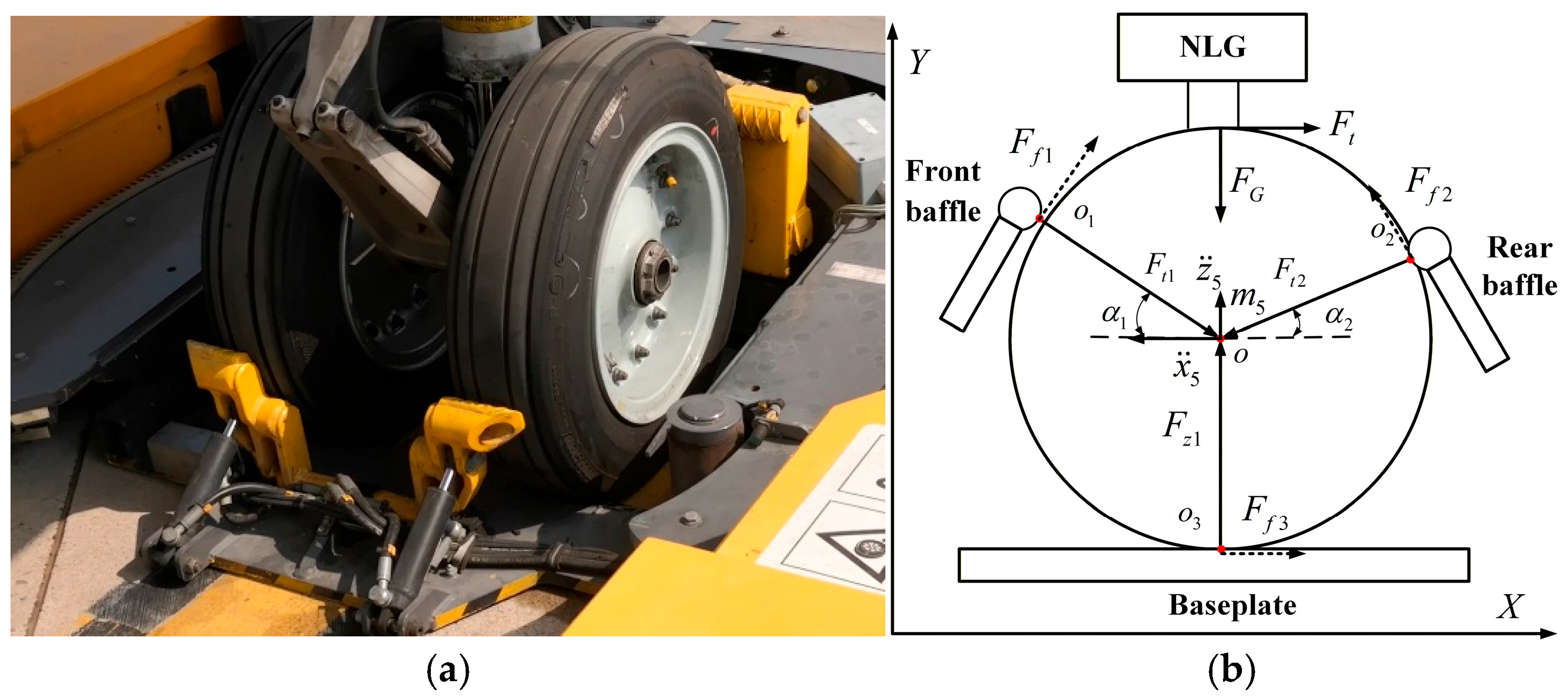

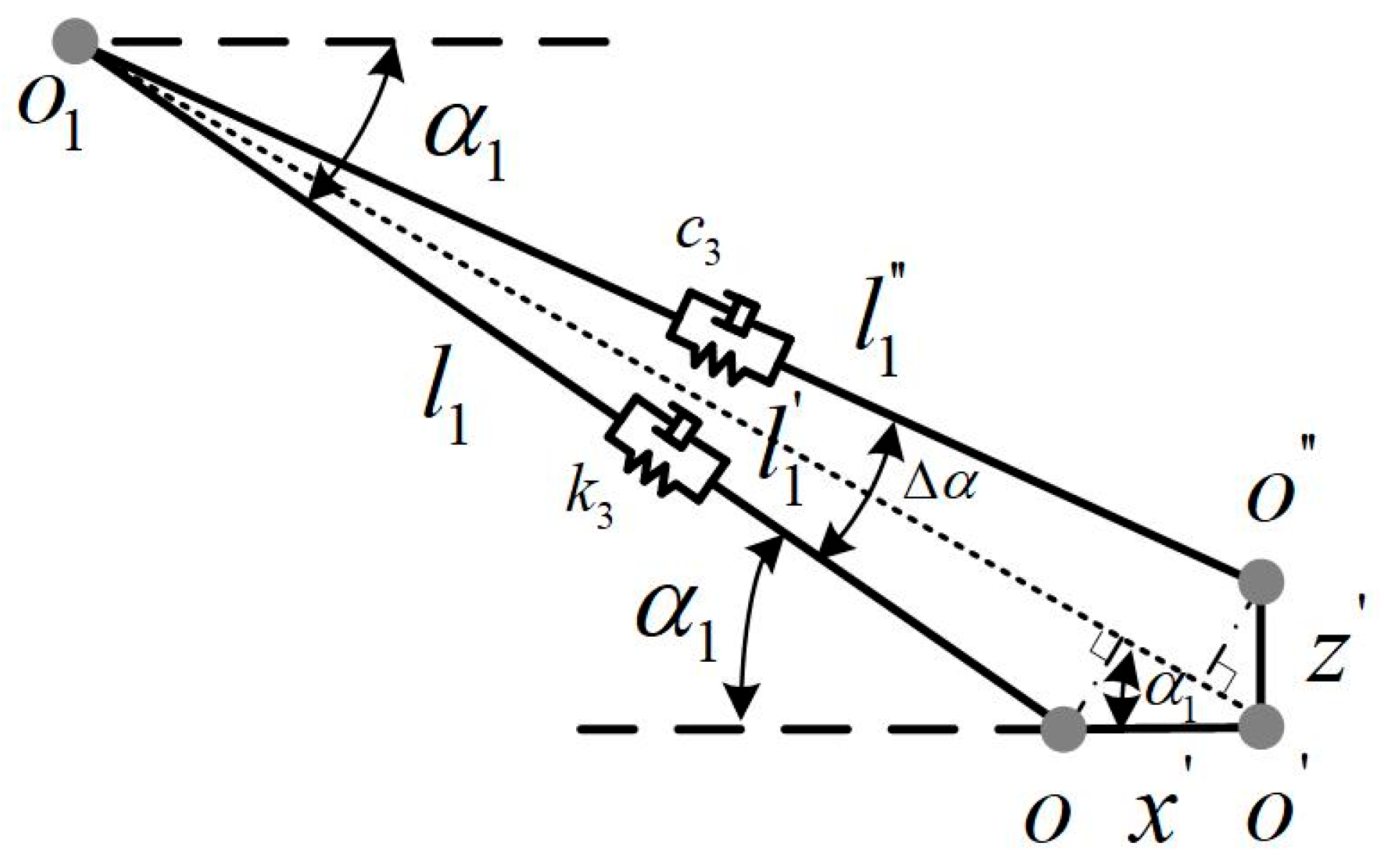

2.2. PUHS–Aircraft Nose Wheel Contact Model

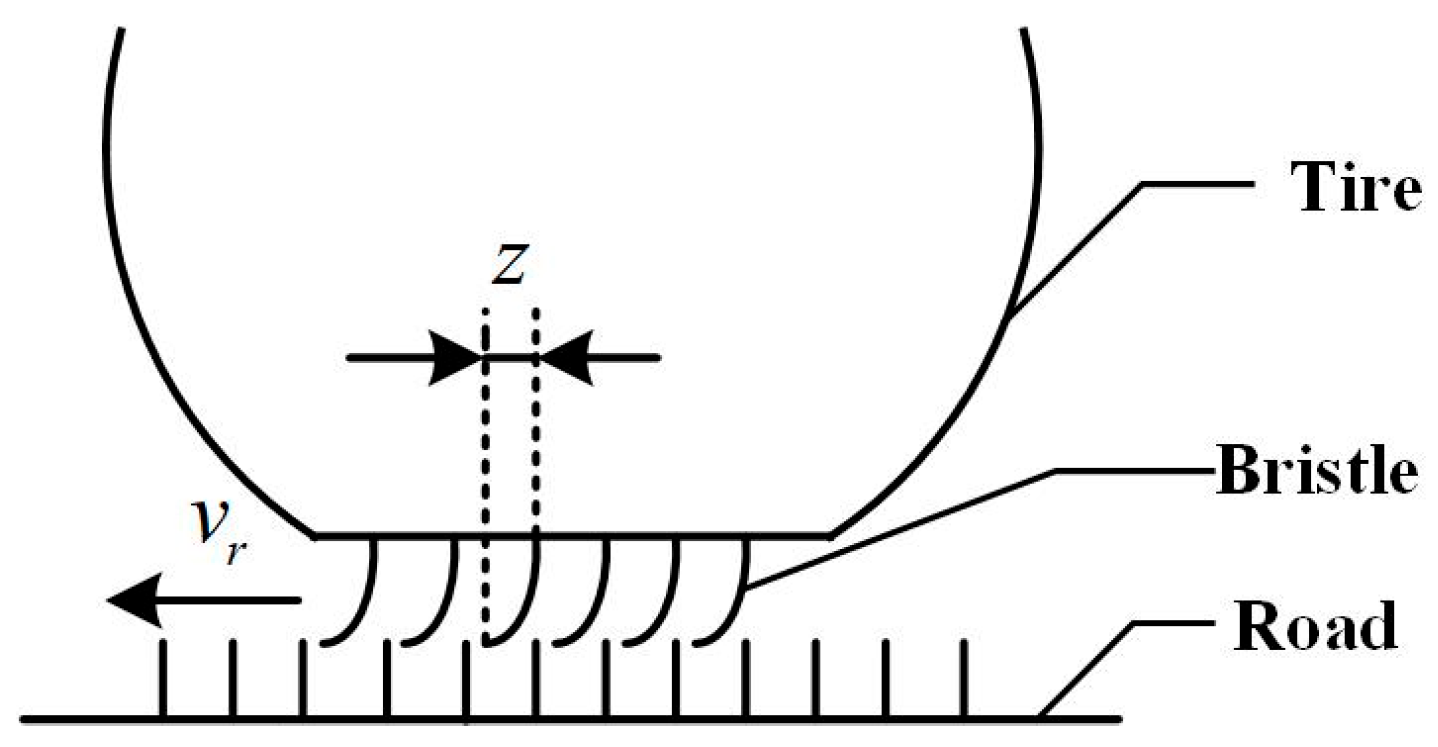

2.3. Tire Model

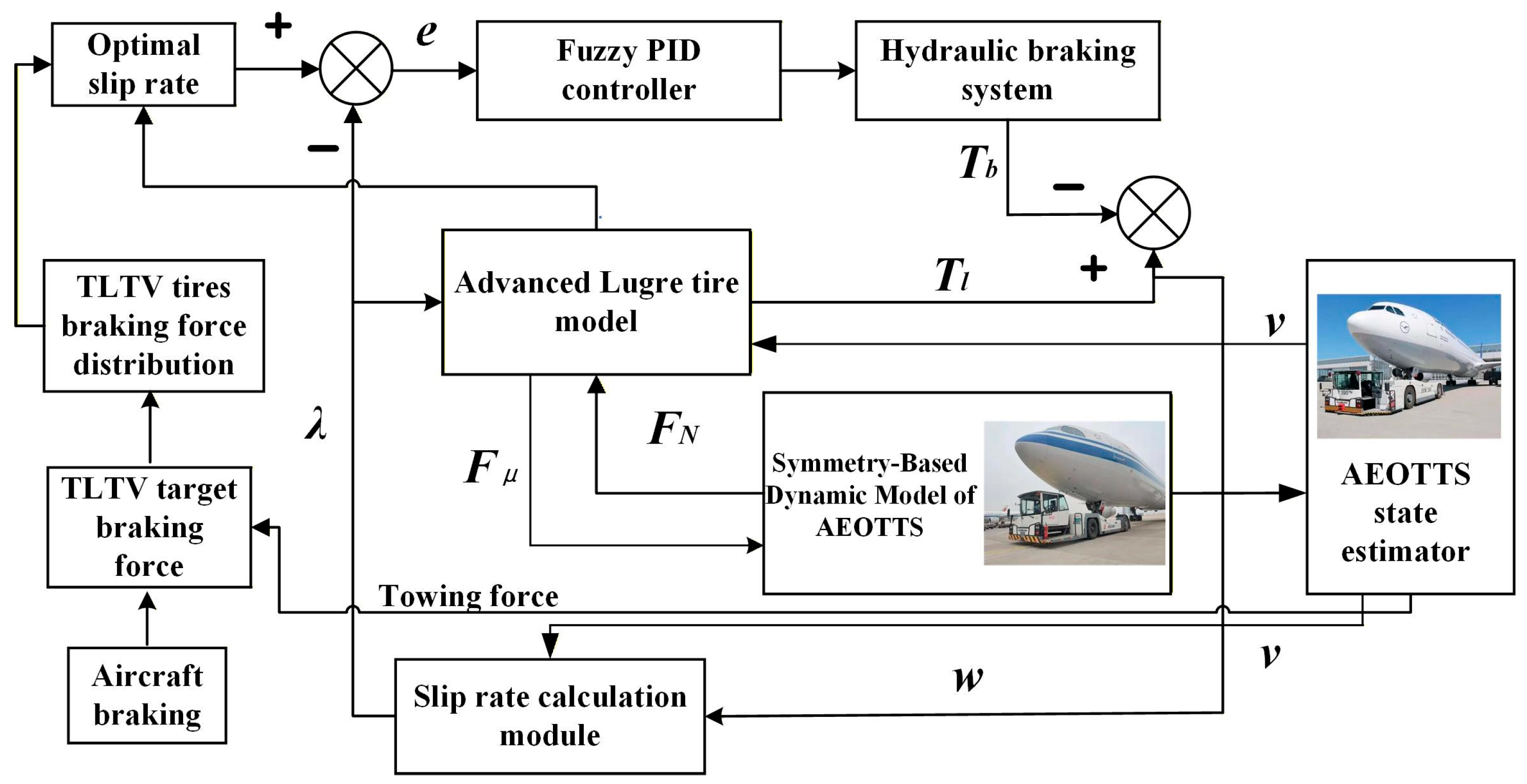

3. Follow-Up Control System of the AEOTTS Symmetric Model

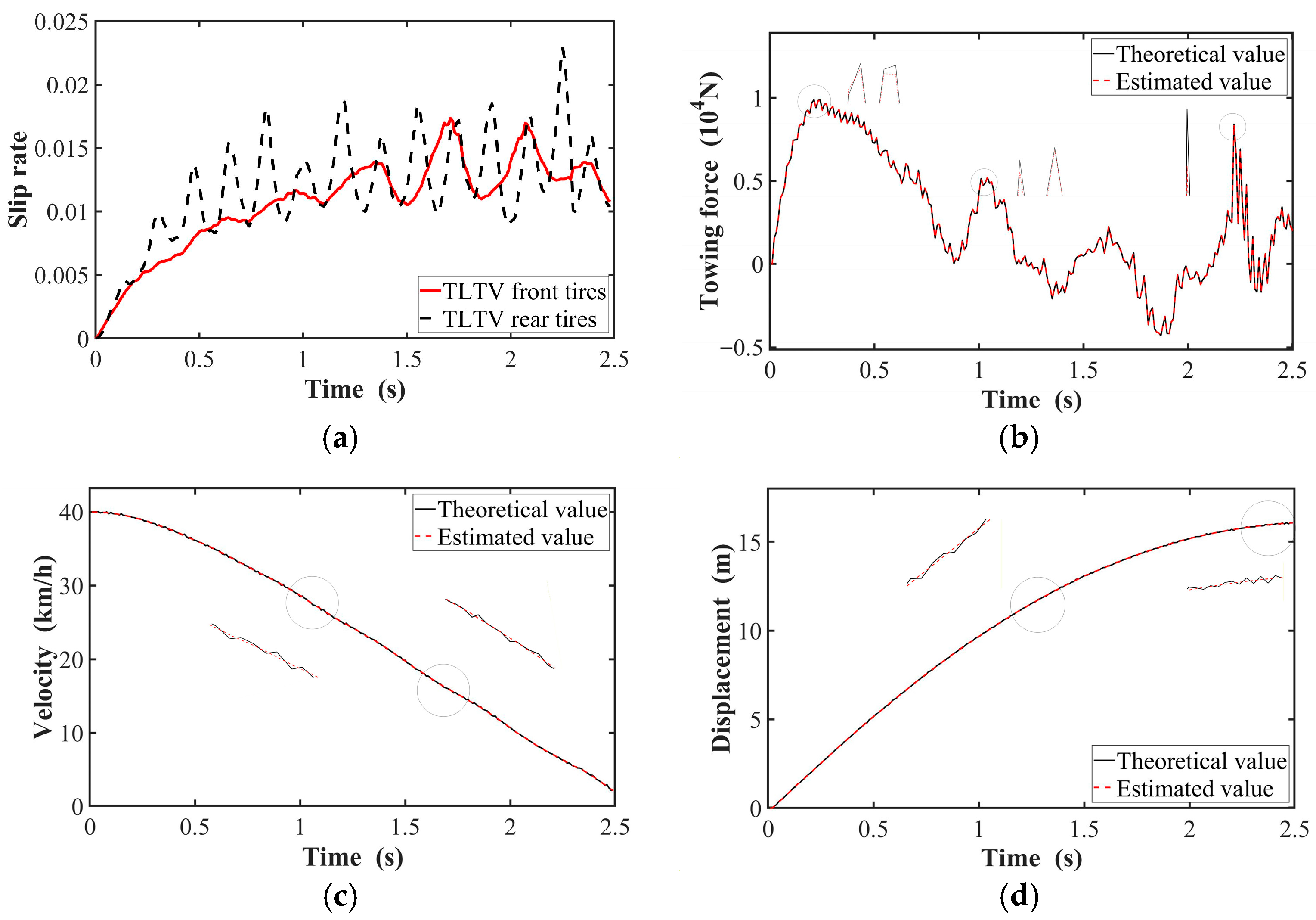

3.1. AEOTTS State Estimation

3.2. AEOTTS Follow-Up Control

Braking Force Computation and Distribution

3.3. Unevenness Runway Input

4. Follow-Up Braking Analysis of AEOTTS Under Complex Conditions

4.1. Analysis of Follow-Up Braking Characteristics

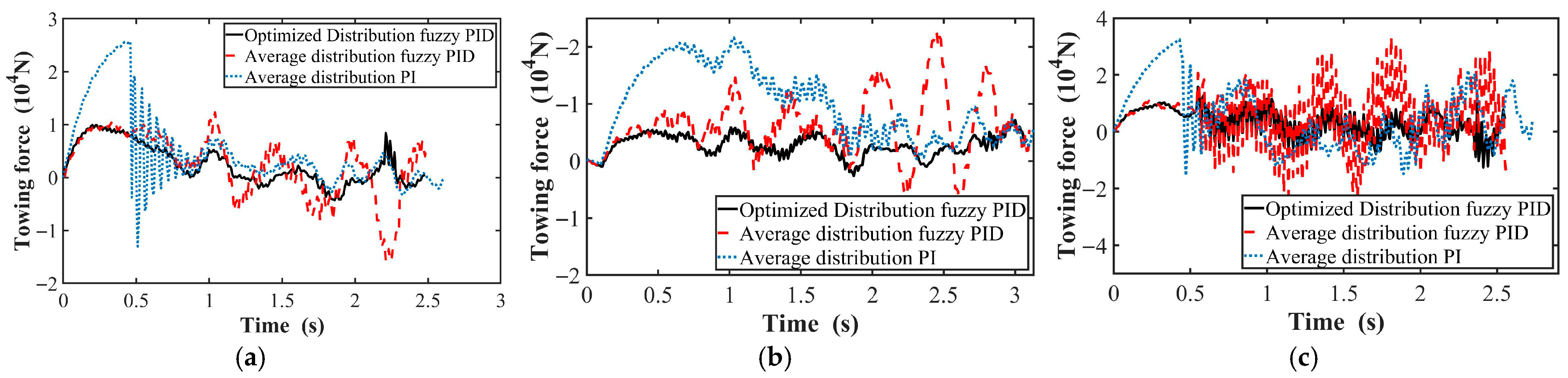

4.2. Analysis of Towing Force on NLG

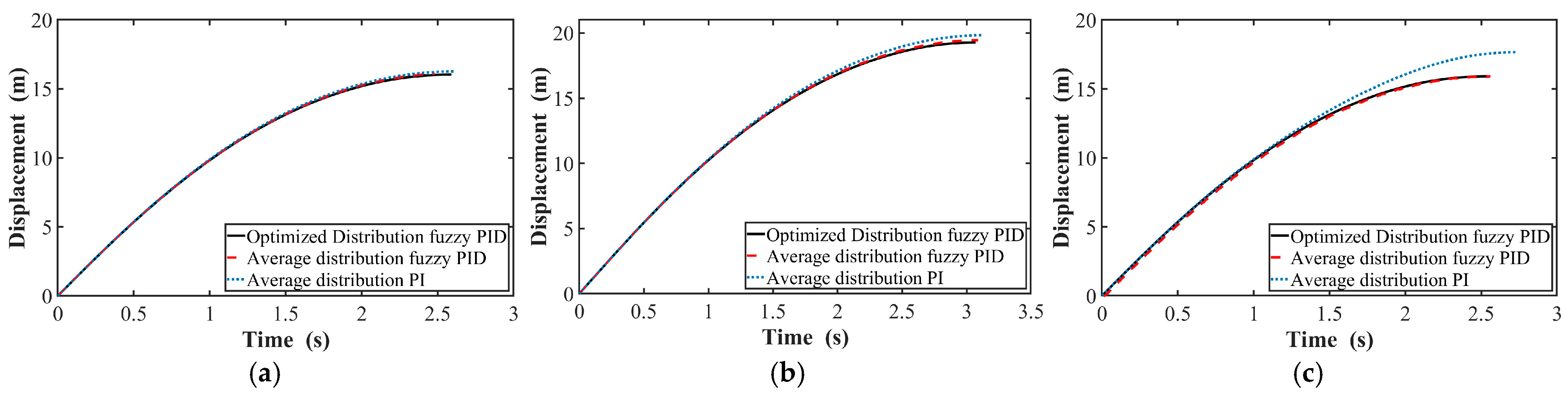

4.3. Analysis of Braking Distance

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on the refined symmetrical dynamic model of the AEOTTS, the follow-up estimator can effectively predict the state changes of the AEOTTS. The maximum error between the estimated and theoretical values of aircraft traction force is 2.7%. Under the follow-up braking control mode, the tire slip rate of the TLTV initially increases and then stabilizes with oscillations, with the front wheels demonstrating superior control performance.

- (2)

- Under three braking conditions considering road adhesion coefficient and runway unevenness, the braking performance of the AEOTTS was compared across three follow-up control modes: average distribution PI control, average distribution fuzzy PID control, and optimized distribution fuzzy PID control. The fuzzy PID follow-up control system based on optimized distribution significantly reduced the towing force on the aircraft’s NLG, with the peak towing force decreasing by up to 68.9% and the RMS value of the force by up to 70.9%. Additionally, the braking distance of the AEOTTS was reduced by up to 9.9%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Komite Nasional Keselamatan Transportasi. Aircraft Accident Investigation Report; Komite Nasional Keselamatan Transportasi: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham, D.; Stephens, M.; Chymiy, A. Deriving Benefits from Alternative Aircraft-Taxi Systems; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H.; Li, G.Y. Kinematic simulation of clamping/holding mechanism for no-rod airplane tractor based on Pro/Engineer. Hoisting Conveying Mach. 2008, 4, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Z.; Yu, H.B. Kinematics analysis of the clamping and lifting mechanism of new aircraft tractor. Hoisting Conveying Mach. 2019, 1, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.W.; Wu, Z.H.; Zhang, W. Kinematics Analysis for Clamping and Lifting Mechanism of Tow-bar-less Aircraft Tractor. Mach. Tool Hydraul. 2015, 43, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.C. Structure Design and Analysis of Lifting Mechanism of Aircraft Tractor. J. Shandong Univ. Aeronaut. 2020, 36, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.Q.; Qi, J.Y.; Gao, X. Design of clamping and lifting mechanism for towbarless aircraft tractor. Hoisting Conveying Mach. 2019, 18, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.Z.; Huang, A.; Shi, P.C. Anti-vibration optimization design for clamp-lifting device on aircraft tractors. J. Mech. Strength 2022, 44, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.T. Research on Braking Performance of the Towbarless Aircraft Tractor. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S. Research on Simulation of Braking Performance of Carrier Aircraft Tracting System. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.K.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.W.; Liu, J.H.; Zhu, H.J.; Liu, Y.X.; Qin, J.H. Review on aircraft towing taxi technologies. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2023, 23, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.J.; Zhou, L.J.; Song, Q.; Zhang, D.F. Simulation research on braking safety properties of aircraft traction system. Key Eng. Mater. 2010, 419, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, H.; Qi, J.; Sun, H.; Tian, X.; Liu, H.; Fan, X. An Acquisition method of agricultural equipment roll angle based on multi-source information fusion. Sensors 2020, 20, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Fu, Z.; Xu, Q. An adaptive multi-dimensional vehicle driving state observer based on modified Sage-Husa UKF algorithm. Sensors 2020, 20, 6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C. Research on Vehicle State Estimation with Steer-by-Wire System Based on Nonlinear Estimation Method. Ph.D. Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Gu, L.; Dong, M. Vehicle system state estimation based on adaptive unscented Kalman filtering combing with road classification. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 27786–27799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yu, Z.; Xiong, L. Anti-lock braking system control design on an integrated-electro-hydraulic braking system. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2017, 1, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Xu, D. Research on anti-lock braking control strategy of distributed-driven electric vehicle. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 162467–162478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, Y. Regenerative braking control strategy to improve braking energy recovery of pure electric bus. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2020, 4, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Lian, Q. Adaptive fuzzy fractional-order sliding mode controller design for antilock braking systems. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2016, 138, 041008–041016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavinejad, E.; Han, Q.-L.; Yang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Vlacic, L. Integrated control of ground vehicles dynamics via advanced terminal sliding mode control. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2017, 55, 268–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, J.F. Analysis on braking stability of towbar-less towing vehicle under steering and braking. J. Mach. Des. 2020, 37, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W. Optimization design of towbarless aircraft tractor frame based on ansys workbench. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 268, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.J.; Qi, K.; Wang, L.W.; Zhang, W. Longitudinal dynamics modeling and braking performance of towbarless aircraft taxiing system on wet roads. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2024, 45, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.; Botha, T.; Hamersma, H. Model-free intelligent control for antilock braking systems on rough roads. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2023, 7, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q. Coherence of phase angle of harmonic superposition components in time domain simulation of road roughness for right and left wheel tracks. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 2019, 39, 1034–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 7031-2005; Mechanical Vibration-Road Surface Profiles-Reporting of Measured Data. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’ s Republic of China. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China, Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2005.

| Symbol | Description | Value | Symbol | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLTV mass | 1.3 × 104 kg | Height from ground to TLTV CG | 0.5 m | ||

| The TLTV’s Pitch moment of inertia | 5.4 × 104 kg·m2 | Height from ground to aircraft CG | 10 m | ||

| Aircraft mass | 6.0 × 104 kg | Height from ground to aircraft nose wheel center | 0.1 m | ||

| The aircraft’s pitch moment of inertia | 4.7 × 106 kg·m2 | MLG stiffness coefficient | 1 × 106 N·m−1 | ||

| NLG unsprung mass | 400 kg | MLG damping coefficient | 40,000 N·s·m−1 | ||

| MLG unsprung mass | 2000 kg | Spacing between TLTV CG and the front axle | 0.5 m | ||

| Stiffness coefficient TLTV of front wheel | 4 × 106 N·m−1 | Spacing between TLTV CG and aircraft nose wheel | 2 m | ||

| Damping coefficient of TLTV front wheel | 1200 N·s·m−1 | Spacing between aircraft nose wheel and TLTV rear axle | 1.5 m | ||

| Dtiffness coefficient of TLTV rear wheel | 5 × 106 N·m−1 | Spacing between TLTV CG and the rear axle | 3.5 m | ||

| Damping coefficient of TLTV rear wheel | 1200 N·s·m−1 | Spacing between aircraft CG and the nose wheel | 15 m | ||

| Stiffness coefficient of aircraft nose wheel | 2 × 106 N·m−1 | Spacing between aircraft CG and the main wheel | 1 m | ||

| Damping coefficient of aircraft nose wheel | 900 N·s·m−1 | TLTV tire rolling radius | 0.39 m | ||

| Aircraft main wheel stiffness coefficient | 1 × 107 N·m−1 | Aircraft main wheel rolling radius | 0.56 m | ||

| Aircraft main wheel damping coefficient | 4000 N·s·m−1 | TLTV wheel moment of inertia | 7.8 kg·m2 | ||

| NLG equivalent stiffness coefficient | 2 × 105 N·m−1 | Aircraft main wheel moment of inertia | 9.2 kg·m2 | ||

| NLG equivalent damping coefficient | 1 × 104 N·s·m−1 |

| Lugre Model Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| 138 | |

| 0.001 | |

| 0.456 | |

| 1.4 | |

| 5 |

| Braking Condition | Maximum NLG Towing Force (104 N) | NLG Towing Force RMS Value (104 N) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Distribution PI | Average Distribution Fuzzy PID | Optimized Distribution Fuzzy PID | Average Distribution PI | Average Distribution Fuzzy PID | Optimized Distribution Fuzzy PID | |

| standard braking | 2.56 | 1.59 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 0.46 |

| wet runway braking | 2.18 | 2.29 | 0.71 | 1.17 | 0.83 | 0.34 |

| Class C runway braking | 3.25 | 3.37 | 1.57 | 1.30 | 1.24 | 0.59 |

| Braking Condition | Braking Distance (9 m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Distribution PI | Average Distribution Fuzzy PID | Optimized Distribution Fuzzy PID | |

| standard braking | 16.26 | 16.09 | 16.03 |

| wet runway braking | 19.83 | 19.41 | 19.27 |

| Class C runway braking | 17.66 | 15.93 | 15.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qi, K.; Li, G.; Chow, W.K.; Li, M. Research on the Follow-Up Braking Control of the Aircraft Engine-Off Taxi Towing System Under Complex Conditions. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2131. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122131

Qi K, Li G, Chow WK, Li M. Research on the Follow-Up Braking Control of the Aircraft Engine-Off Taxi Towing System Under Complex Conditions. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2131. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122131

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Kai, Gang Li, Wan Ki Chow, and Mengling Li. 2025. "Research on the Follow-Up Braking Control of the Aircraft Engine-Off Taxi Towing System Under Complex Conditions" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2131. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122131

APA StyleQi, K., Li, G., Chow, W. K., & Li, M. (2025). Research on the Follow-Up Braking Control of the Aircraft Engine-Off Taxi Towing System Under Complex Conditions. Symmetry, 17(12), 2131. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122131