1.1. Background

Modern target tracking systems (such as air defense early warning, air traffic control, missile defense, and autonomous driving perception systems) all rely on radar as the primary long-range, all-weather detection tool [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Radar sensors periodically scan the environment, detect targets, and generate raw track points [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, radar track data has the following characteristics: inherent noise and uncertainty, as radar measurements are subject to thermal noise, clutter interference, multipath effects, and other factors, leading to significant random errors in the obtained position and velocity information; limited angular resolution and uneven distance measurement accuracy, meaning that a single measurement cannot reflect the target’s true state; discrete sampling characteristics, as radar operates on a fixed cycle, so the target’s state can only be ‘captured’ at discrete time points; and nonlinear and non-ideal motion, as radar typically measures in polar coordinates, while targets often move in Cartesian coordinates and frequently maneuver. Coordinate transformation introduces nonlinear errors, and the target’s actual motion often deviates from simplified motion models. These issues, dictated by both radar hardware characteristics and the detection environment, result in raw track points naturally containing noise disturbance, data gaps, position jumps, and accuracy limitations. Without effective processing, such data cannot directly support high-reliability situational awareness, early warning decisions, or weapon guidance [

18].

To achieve real-time, accurate, and stable estimation of a moving target’s state, track filtering serves as the core component of target tracking, playing an irreplaceable foundational role. Track filtering processes the sequence of sensor detection points through temporal fusion, eliminating noise, compensating for uncertainty, and associating measurements with the true target motion, ultimately generating a smooth, continuous, and reliable target track that can be used to predict future positions [

19,

20].

1.2. Current Methods Review

The historical development of filtering algorithms has broadly progressed through three distinct phases: Initially dominated by elementary techniques such as moving averages and polynomial fitting, subsequent evolution shifted toward state-space model-based methodologies, culminating in the current era, where machine learning approaches demonstrate significant potential, enabled by advances in computational capabilities. Among conventional methods, the Kalman Filter (KF) [

21] gained widespread adoption owing to its optimal estimation properties, though its inherent linearity constraints limit efficacy in nonlinear systems. To address this limitation, researchers developed enhanced variants including the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) and Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF).

The Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) utilizes local linearization through first-order Taylor expansion to approximate nonlinear system dynamics and observation models, subsequently implementing the standard Kalman filtering framework for state estimation [

22]. Primary advantages of this approach include computational efficiency, primarily attributable to the sole requirement of Jacobian matrix computation; effective applicability in real-time operational scenarios; and operational maturity in engineering implementations, with demonstrated stability in weakly nonlinear systems. Nevertheless, fundamental limitations persist: non-negligible linearization errors arising from first-order truncation, inducing systematic state-space distortion; precipitous accuracy deterioration or filter divergence under strongly nonlinear conditions; analytical intractability of Jacobian derivations for complex systems, necessitating error-prone numerical approximations that elevate computational complexity and uncertainty propagation; and heightened sensitivity to initialization inaccuracies and parametric mismatches, potentially inducing catastrophic failure through linearization breakdown.

The Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) propagates the statistical properties of nonlinear systems through a set of deterministically selected sigma points via the unscented transform (UT), thereby circumventing the linearization process. Core advantages of this methodology include superior estimation accuracy, attributable to full capture of second-order statistical characteristics in nonlinear systems; demonstrated performance advantages over Extended Kalman Filters (EKFs) for high-maneuvering target tracking [

23,

24]; elimination of Jacobian matrix computations, simplifying implementation and mitigating model-mismatch risks; and enhanced numerical stability with robustness against parametric uncertainties and noise non-stationarity. However, inherent limitations require attention: computational complexity escalation resulting from the 2

n + 1 sigma-point requirement, where

n denotes state dimension, constraining real-time performance in high-dimensional systems; and inherent Gaussian noise assumption, leading to persistent estimation bias under heavy-tailed distributions within complex electromagnetic environments.

The Particle Filter (PF) algorithm approximates the posterior probability distribution through large-scale Monte Carlo simulations with weighted particles. While effectively addressing nonlinear and non-Gaussian system constraints, this methodology exhibits three fundamental limitations: excessive computational load inherent to particle propagation mechanisms; progressive particle degeneracy requiring systematic resampling interventions; compromised real-time capability stemming from algorithmic complexity; and significant dependency on empirical parameter tuning that undermines theoretical rigor [

25].

These constraints collectively reveal the core inadequacy of conventional filtering paradigms: contemporary frontier applications demand increasingly stringent operational requirements: including high-fidelity estimation, adaptive dynamics, and rapid response latency, which cannot be satisfied solely by predetermined physical models and stationary statistical assumptions [

26,

27]. Fortunately, there is rapid development in deep learning technology, which demonstrates, in particular, excellent performance in nonlinear modeling, pattern recognition, and end-to-end learning.

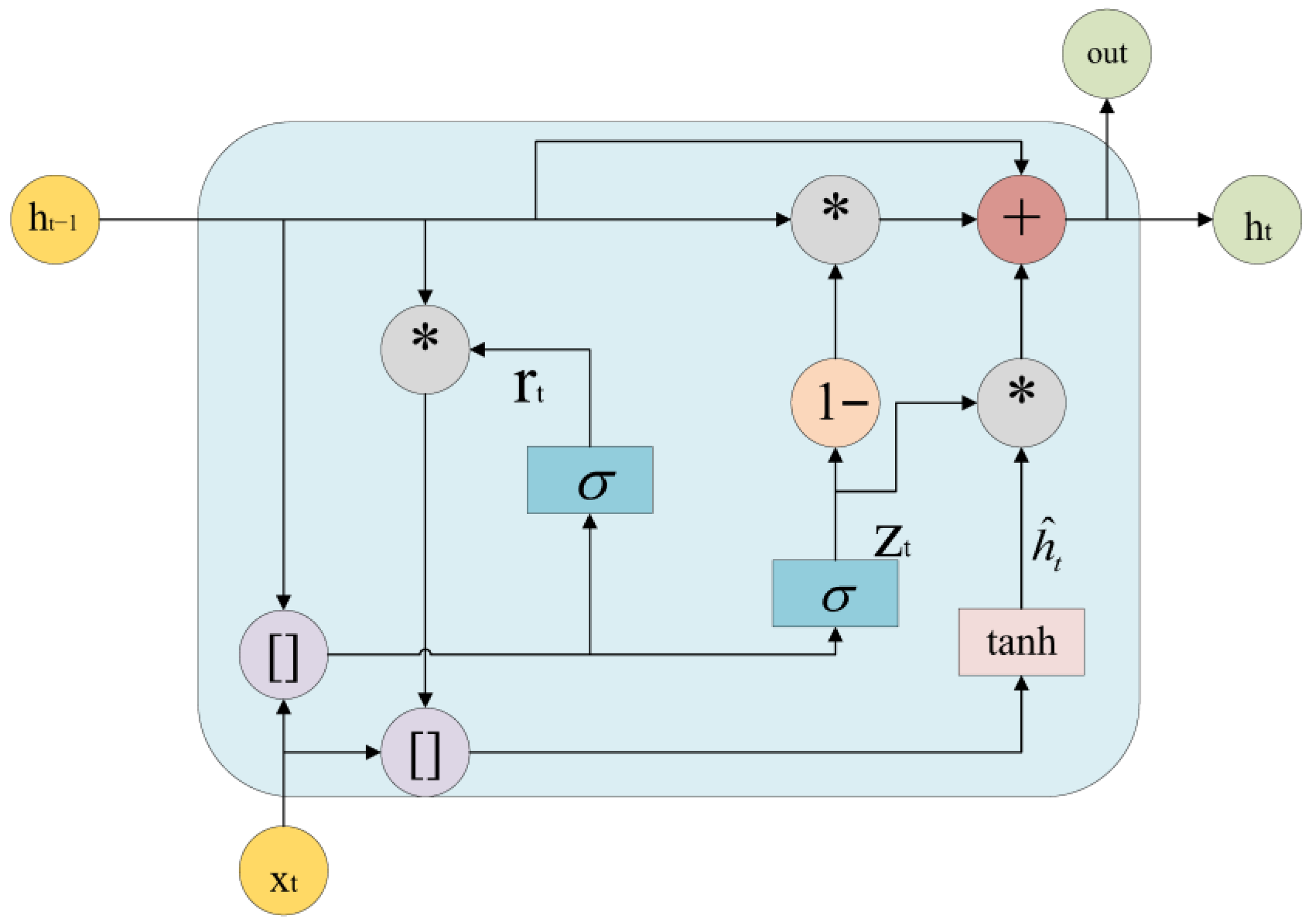

The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), formally instantiated in Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, resolves the long-term temporal dependency problem inherent in vanilla RNNs through three synergistic mechanisms: superior sequential modeling capacity for temporal forecasting tasks, intrinsic resistance to vanishing gradients, and length-agnostic input handling eliminating fixed-window constraints. Fundamental limitations comprise computational inefficiency with gate operations incurring three times higher training overhead than convolutional counterparts [

28,

29]; inherent sequential dependency hindering GPU parallelization; suboptimal short-term feature extraction due to sigmoidal gate inertia; and delayed response to abrupt state transitions from temporal smoothing effects.

The convolutional neural network leverages parameterized kernel operators to extract hierarchical spatial representations, establishing translation-equivariant feature hierarchies through its architectural inductive bias. Core advantages include spatially-localized feature extraction achieving state-of-the-art performance in image/radar point cloud processing; massive parallelism from kernel operation independence; and spatial translation invariance ensuring consistent recognition under coordinate perturbations. Fundamental limitations encompass temporal modeling deficiency requiring auxiliary architectures for dynamic sequence processing; constrained receptive fields limiting large-scale dependency capture; and input dimensionality rigidity typically mandating fixed-size inputs due to fully connected layer constraints [

30].

A graph convolutional neural network is based on a node-edge structure modeling relationship, and aggregates neighborhood information through message transmission [

31,

32]. Advantages include outstanding relationship reasoning capability, suitable for multi-source sensor network interaction modeling, dynamic structure adaptation, strong integration of graph and heterogeneous graph supporting topology change, and capable of processing different types of nodes/edges. Disadvantages include high computational complexity, exponential growth of neighborhood aggregation with the number of connections, risk of over-smoothing, convergence of node characteristics caused by deep GCN, difficulty of industrial deployment, and great difficulty in real-time graph construction/update in embedded systems [

33,

34].

With the development of deep learning, a single network can no longer meet task requirements, so the mainstream is now moving towards hybrid network models.

Xu, Y proposed the LSTM-MHA architecture, using LSTM networks to capture temporal dependencies, and the MHA mechanism to enhance focus on critical time steps [

35]. This method enhanced the recognition of key events in long sequences, but MHA introduced additional computational overhead [

36]. Zeng X proposed the GRU-Attention architecture. GRU simplifies time series modeling, and the attention mechanism adaptively weights historical states. Its computational efficiency surpasses that of LSTM-MHA, and attention mitigates the long-term memory decay problem of GRU, but a simple attention mechanism struggles to handle multi-factor interactions. C. Cao proposed the BiGRU-MA architecture. Bidirectional GRU extracts context, and the MA module enhances the memory of historical patterns. It significantly improves robustness to sparse data, and the MA module suppresses repetitive noise patterns, but the bidirectional structure results in latency for streaming predictions [

37,

38,

39]. Yan H proposed the LSTM-Transform architecture [

40]. It combines the local smoothness of LSTM with the global relational capability of Transformer, but the hybrid architecture results in complex gradient propagation paths, causing unstable training and increased latency [

41]. Gao Z proposed the TCN and Dual Attention architecture. It uses a TCN to capture long-term dependencies, channel attention to weight sensor features, and temporal attention to focus on critical moments. Its parallel-computed temporal convolution is three times faster than RNNs, and the dual attention mechanism addresses the multi-sensor heterogeneous feature fusion problem, but tuning the spatiotemporal attention coupling design is difficult [

42]. Xu, Y proposed the CNN-biLSTM-MHA architecture. It uses a CNN to extract spatial features, biLSTM to model spatiotemporal evolution [

43,

44], and MHA to focus on key regions. It simultaneously captures environmental semantics and temporal dynamics, and uses MHA to enhance sensitivity to key spatial regions, but the four-stage computational flow results in high latency [

45].

Table 1 is as shown above. Traditional methods are either applicable only to linear systems, weakly linear systems, or Gaussian systems, or their computational complexity increases sharply as the time series grows. Deep learning methods, on the other hand, face issues such as vanishing gradients, exploding gradients, risk of overfitting, slow convergence, limited memory capacity, and difficulty in learning features in complex scenarios. The latest deep learning methods focus on hybrid networks, which usually also result in problems such as a large number of parameters, high computational complexity, and slow convergence.

It can be seen that under the above frontier and key application background, the era calls for a new generation of filtering theory, model, and algorithm that can meet the three core requirements of “high precision”, “strong robustness”, and “hard real-time”.

1.3. Proposed Solution

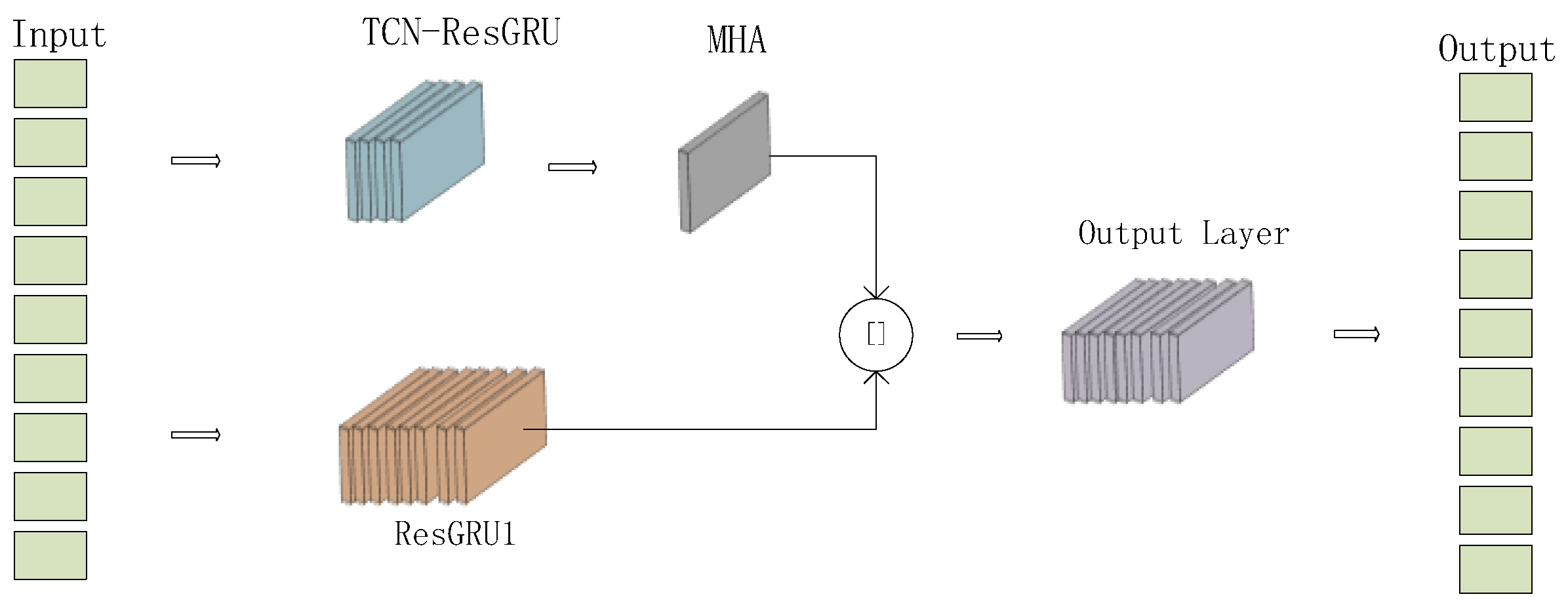

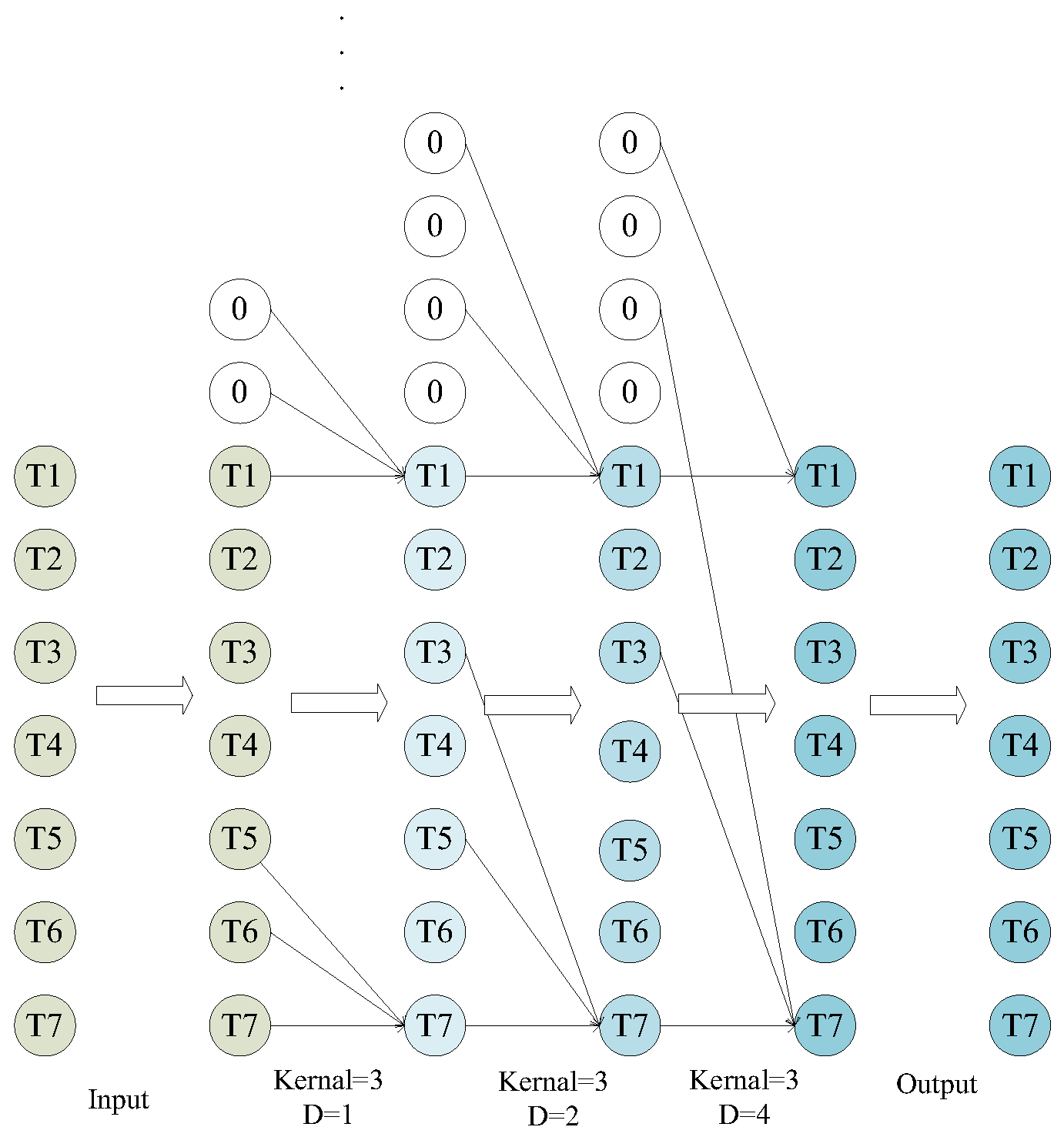

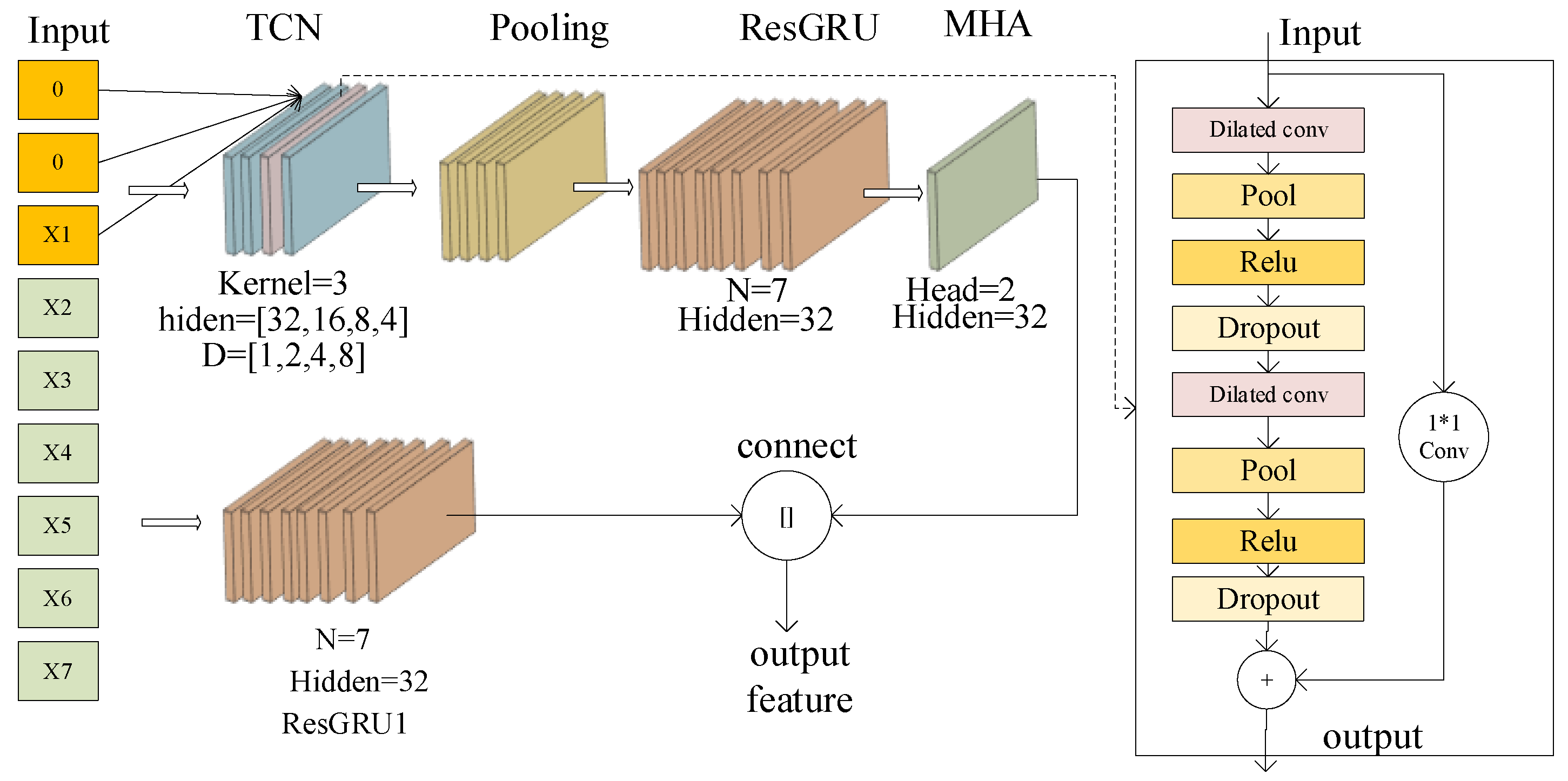

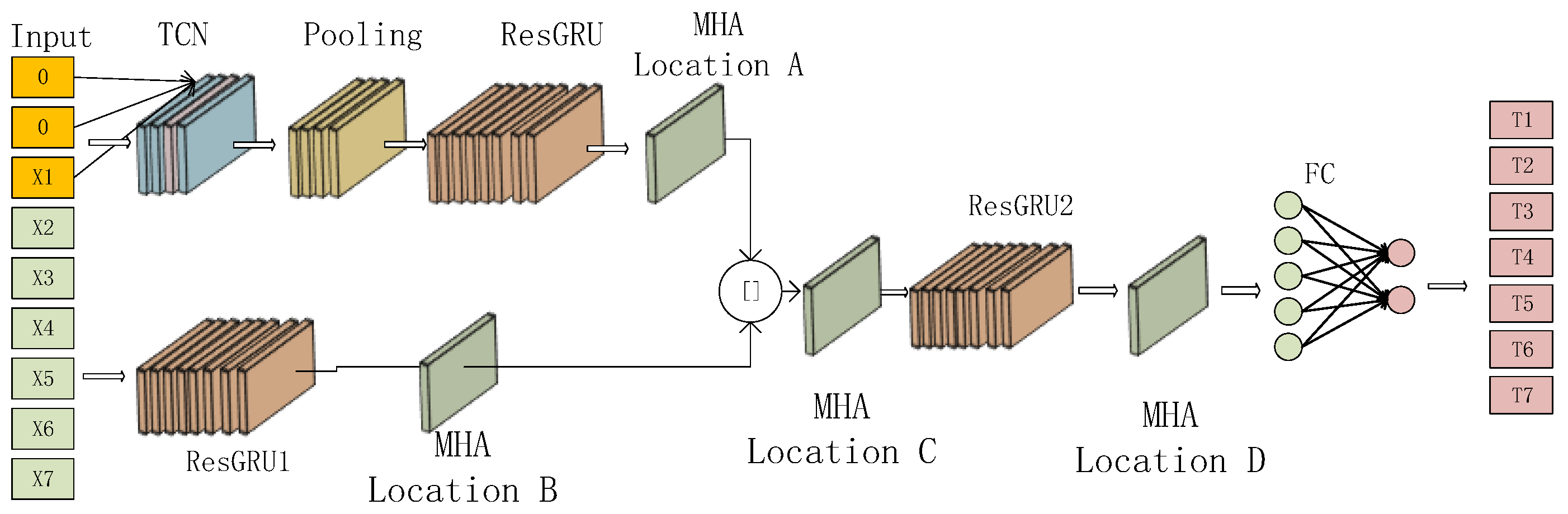

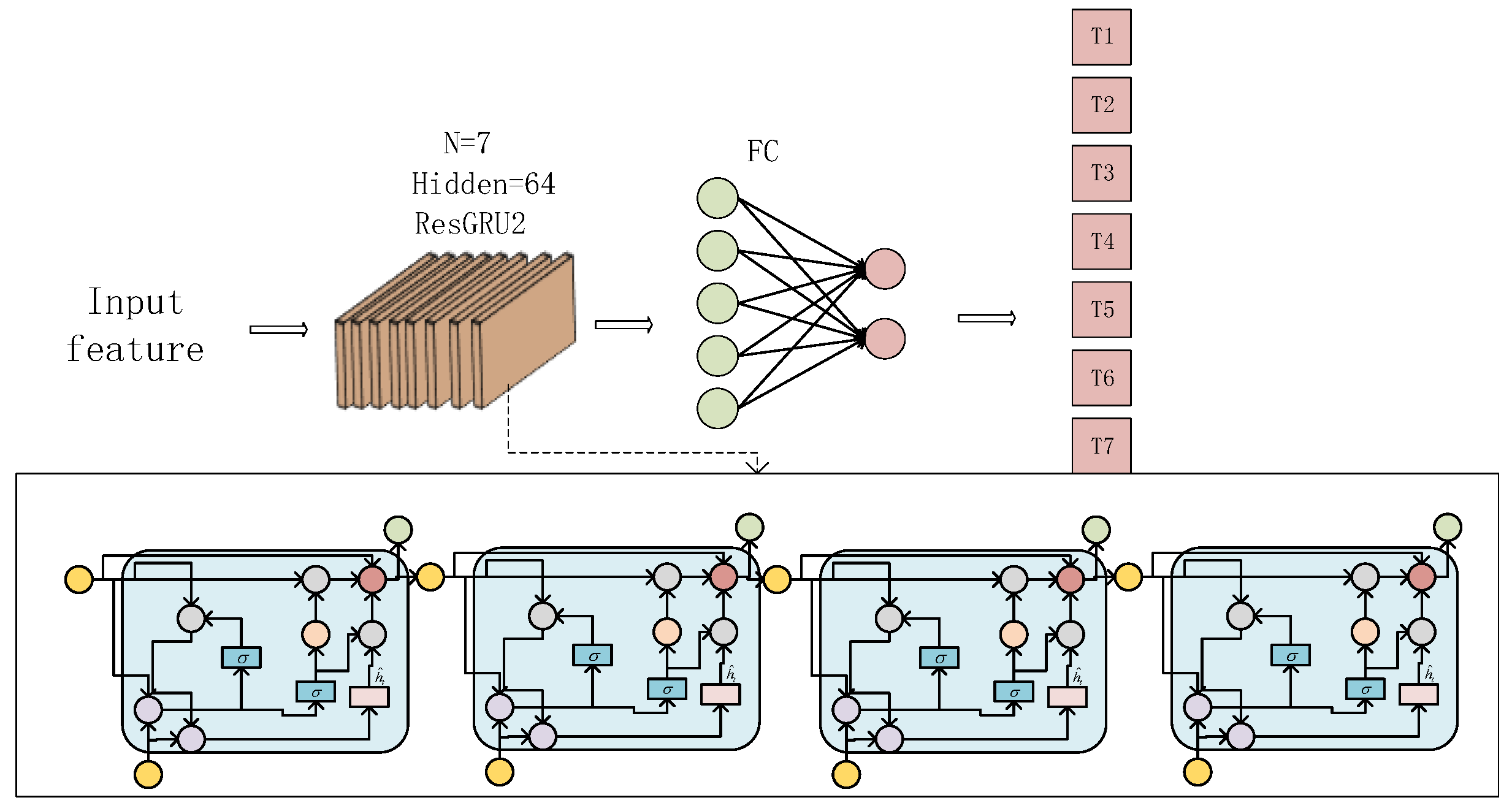

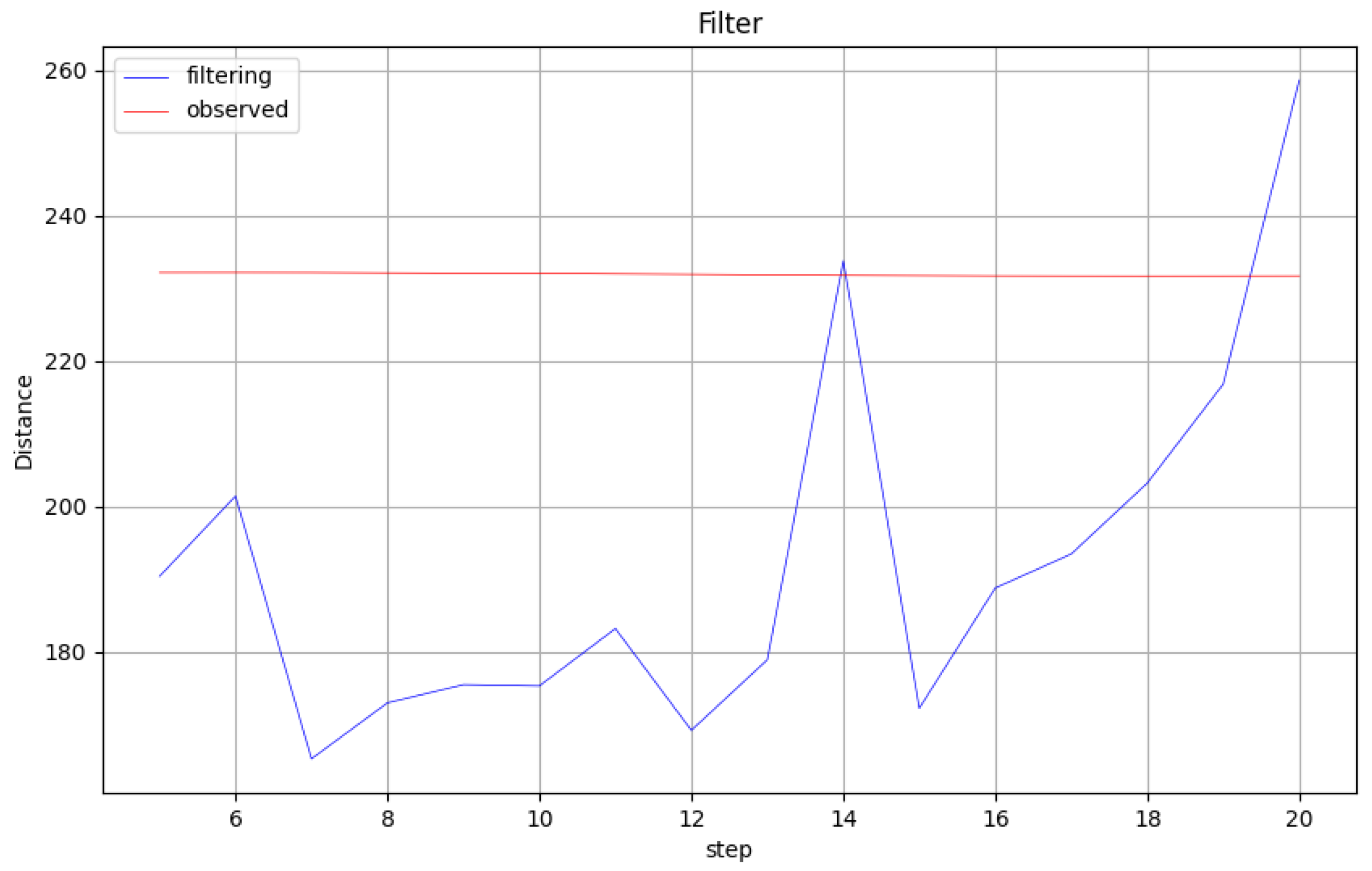

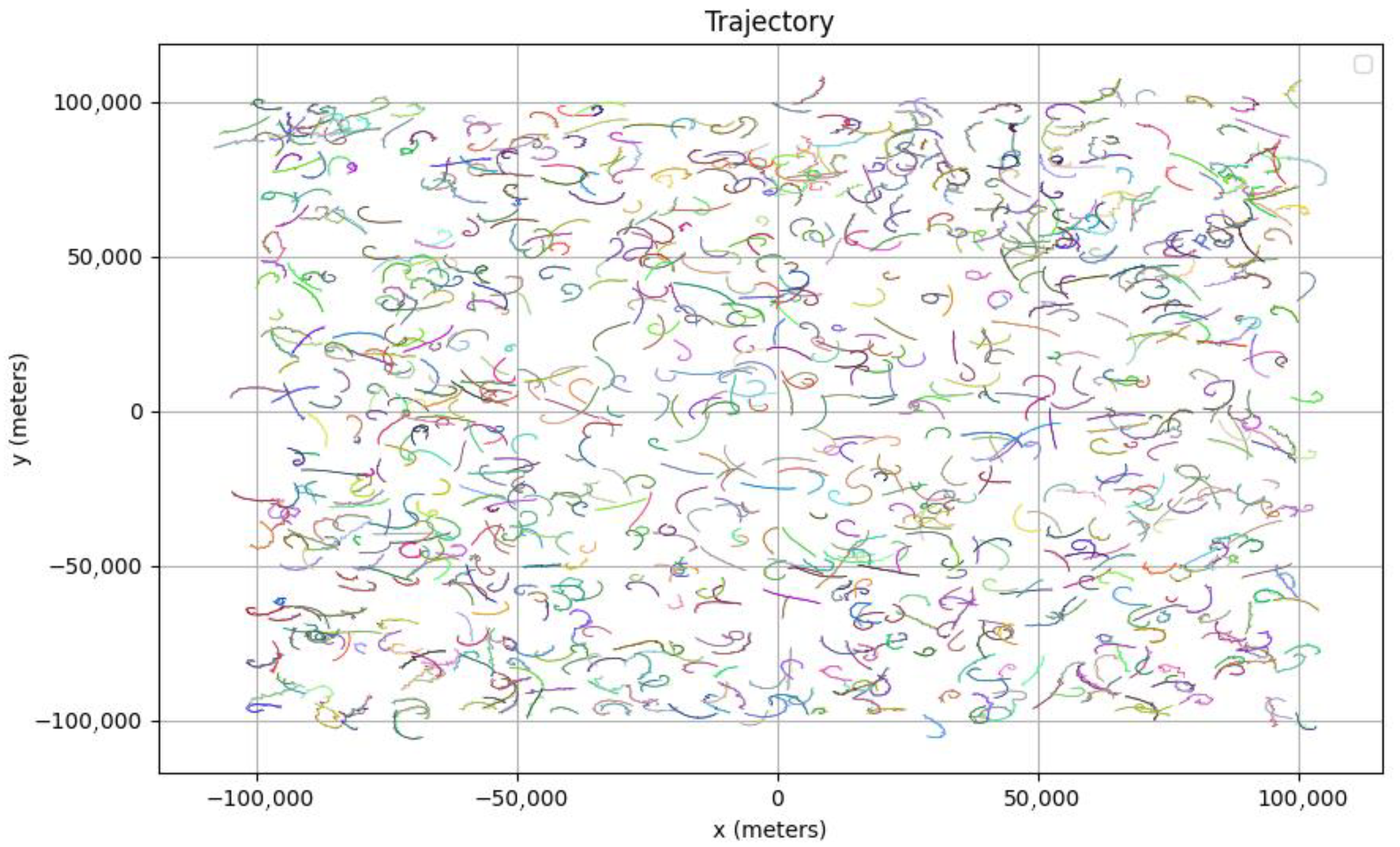

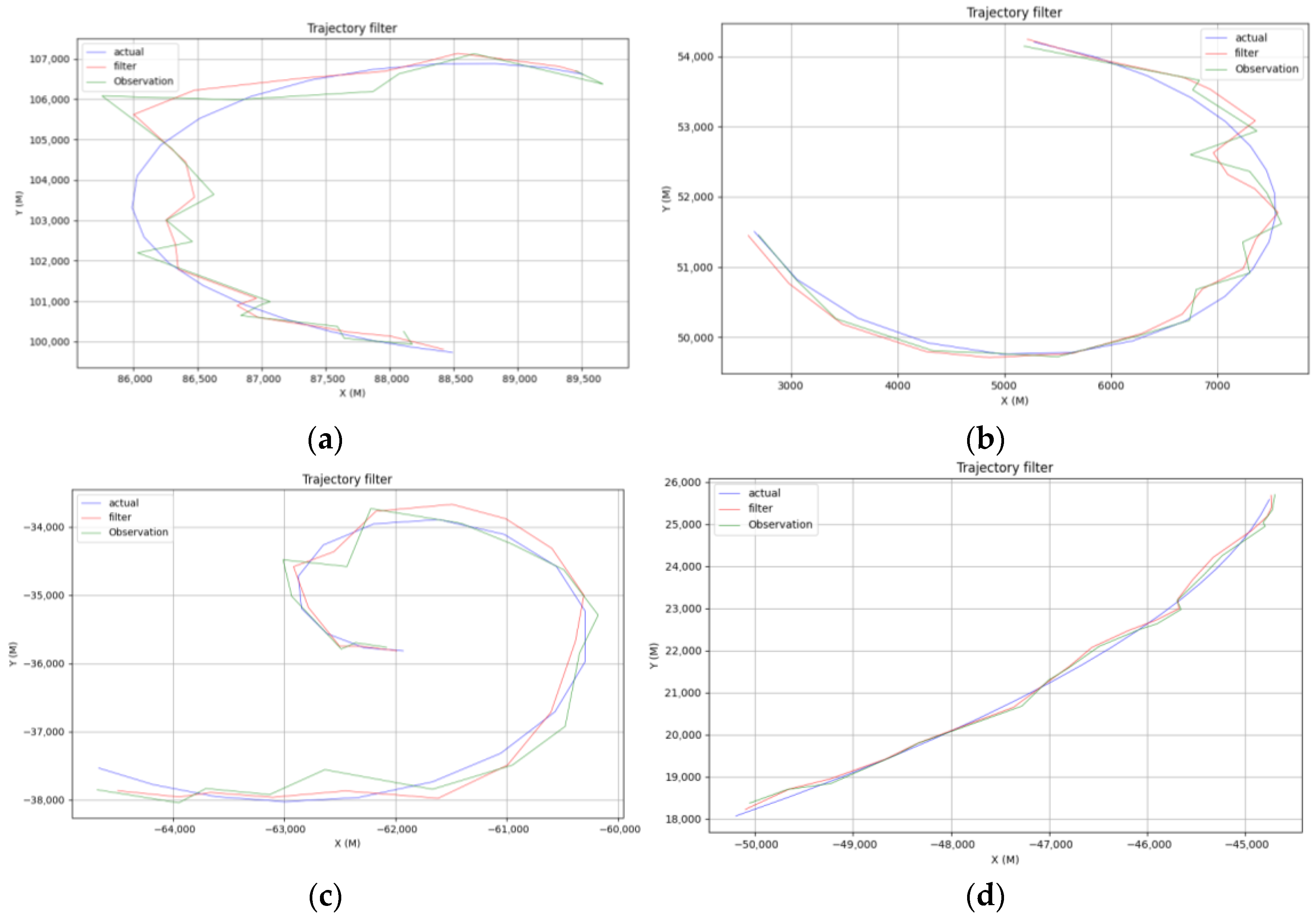

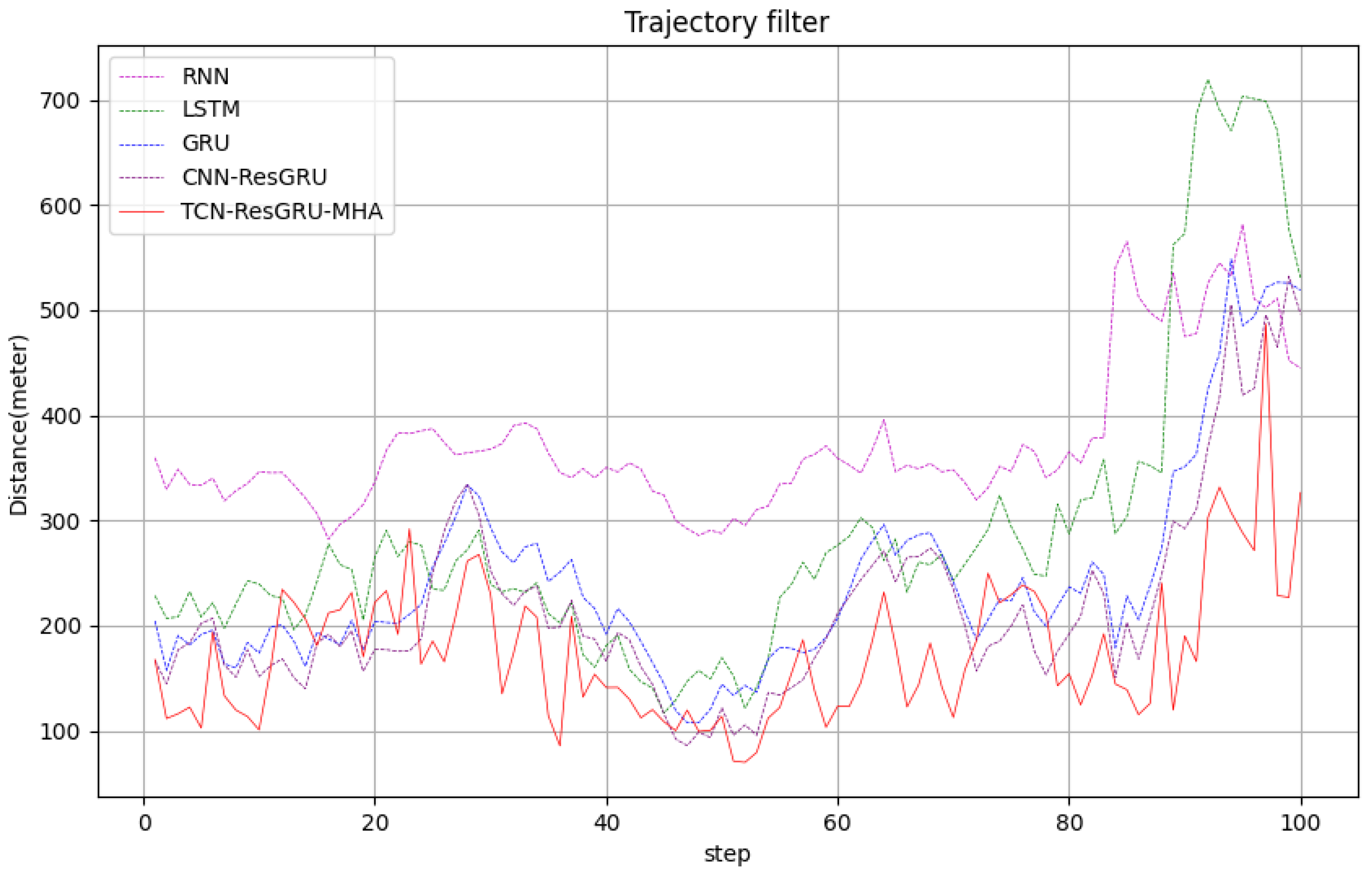

To address the above challenges in track filtering, this study proposes a novel TCN-ResGRU-MHA hybrid model that integrates temporal feature extraction and adaptive weighting mechanisms. The framework first uses a sliding window to sample the original data and divide it into new datasets of fixed length. On the basis of this preprocessing, the framework combines three key components: (1) A temporal convolutional network, which uses dilated causal convolution to effectively capture the characteristics of different time scales, while maintaining the advantages of efficient parallel computing of a convolutional neural network, overcomes the shortcomings of a traditional CNN that struggles to capture long-term dependencies. The introduction of residual connection weakens the gradient vanishing problem in deep network training. (2) A residual gate recurrent unit, which integrates long time sequence dependence, introduces a residual module on the basis of the GRU, and converts the original network from learning the characteristic of each time step to learning the characteristics of the difference between each time step. (3) The multi-head attention module, which can dynamically weight the time sequence features of the radar track, suppress the noise in the time sequence features or the features that have little effect on the prediction, and make it focus on the key features. This integrated design not only addresses the limitations of individual components, but also produces synergistic effects that significantly improve prediction accuracy. Finally, in order to verify the accuracy and stability of the proposed model, we select simulation data to simulate real radar data, and use different algorithms to conduct comparative experiments to evaluate the performance of the TCN-ResGRU-MHA combined model.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical approach adopted in this study.

Section 3 introduces the proposed radar track filtering method.

Section 4 discusses the experimental results and the corresponding analysis. Finally, the main conclusions are summarized in

Section 5.