1. Introduction

As a strategic transportation mode clearly deployed in the “Outline for Building a Transportation Power”, the vacuum tube maglev train relies on its breakthrough ultra-high-speed characteristics—the target speed can exceed 1000 km per hour—as well as ultra-low energy consumption levels and extreme operational efficiency, which lead to disruptive changes in the ground transportation system. The train runs inside a cylindrical narrow low vacuum metal pipe, and the resistance generated by mechanical friction can be eliminated by means of magnetic levitation technology, while the aerodynamic noise and energy consumption can be minimized by combining the near-vacuum environment, that is, the synergy between superconducting magnetic levitation technology and vacuum pipe realizes supersonic “near-ground flight” [

1]. In recent years, China’s research institutions have made significant progress in vacuum tube maglev technology. For example, Southwest Jiaotong University built a prototype test platform [

2] and later launched a dynamic test platform with a design speed of 1500 km/h [

3]. Additionally, the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation plans to build a test line in Datong [

4]. These efforts highlight the growing interest and capability in this field. When operating in a sealed metal pipe near vacuum, the aerodynamic resistance is significantly reduced. The restricted metal cylinder structure becomes the main influencing factor of electromagnetic wave propagation, causing strong waveguide and multi reflection effects. Therefore, it is necessary to capture it in the channel model. A hybrid electromagnetic suspension system (EMS) support structure with low energy consumption and small volume is proposed in reference [

5] for vacuum tube maglev train. Reference [

6] proposes an optimization scheme based on the combination of distributed energy storage and efficient transmission lines, aiming at improving the stability and energy utilization efficiency of train power system. At present, these engineering practices and research are more focused on the fields of power and transportation. When the train runs in the near-vacuum pipeline at a speed of nearly 1000 km/h, the strong constraints of the above environment and the dual challenge of ultra-high-speed mobility pose a greater challenge to the communication quality. The extreme Doppler frequency shift caused by the huge relative velocity results in the sharp change in wireless channel, followed by the millisecond change in relative position of transceiver, which makes the visibility of scatterer in pipeline present transient switch, and the channel response presents strong non-stationarity in time–space simultaneously. Under dual constraints, existing channel models based on open space or low-speed scenarios will no longer be applicable.

In the field of wireless communication research, accurate and efficient channel modeling is the core foundation for in-depth exploration of wireless transmission characteristics and optimization of communication system performance. Time-varying channel modeling faces many complex problems in wireless communication. The key to solve these problems lies in not only accurately identifying the channel characteristics of each time node, but also deeply exploring the dynamic evolution law of channel with time. Especially in special application scenarios such as vacuum pipeline maglev train, it is very important to establish a channel model that fits the actual environment and accurately describes the propagation characteristics and fading laws of radio waves. In reference [

7], the propagation characteristics of radio waves in tunnels with rough surfaces are studied by using vector parabolic equations. Compared with the measured data of tunnels with various shapes, the theory has better modeling accuracy. Reference [

8] combines waveguide mode theory with incident and reflected ray method to study the extra loss in the far field region of tunnel, carries out channel measurement at 3.5 GHz and 5.6 GHz frequency bands in subway tunnel scene, and determines the empirical model between extra loss coefficient and tunnel curvature radius. This method realizes the accuracy equivalent to the ray tracing model. In [

9], transmission characteristics of leaky cable at the 28 GHz frequency band are carried out under short tunnel scenario, and channel statistical parameters such as root Mean Square Delay spread (RMS-DS), K factor, and shadow fading are analyzed. A single-bounce GBSM-MIMO channel model of a leaky cable in a tunnel scenario is proposed in reference [

10]. The channel impulse response of a leaky cable propagation in a tunnel is derived theoretically, and the condition number, channel capacity, and channel correlation coefficient are analyzed by comparing the modeling results with the actual measurement results. Reference [

11] has verified the advantages of 2.4 GHz leaky rectangular waveguide by experimental methods, and proposed the basic architecture of vehicle–ground communication system based on 2.4 GHz leaky rectangular waveguide. In the field of channel modeling for confined spaces, several studies have laid important groundwork. Reference [

12] proposed a three-dimensional geometry-based stochastic model to capture the non-stationarity of the radio channel at 1.8 GHz in rectangular tunnels. Furthermore, reference [

13] applied the GBSM within the vacuum pipeline and proposed a new non-stationary channel model.

Currently, the main wireless channel modeling methods can be divided into deterministic models and stochastic models. Deterministic channel models are usually constructed based on specific propagation environments and antenna configurations, taking into account channel gain, phase, and delay for each possible propagation path, and the construction of propagation environments, including buildings, ground, trees, etc. [

14]. This kind of model has high precision and can truly reflect the actual physical phenomenon, but it needs a lot of computational resources to describe the propagation environment, and the computational complexity increases sharply in complex scenes, so the practical application is limited. A deterministic channel model based on a ray-tracing algorithm is proposed in reference [

15], which is applied to composite high-speed railway scenarios. Doppler domain channel characteristics in transition regions of composite scenarios are studied for statistical analysis. In contrast, the stochastic model uses randomly distributed scatterers to describe the environment and models channel characteristics in a concise and efficient way by adjusting the shape of scattering region or scatterers distribution function. The model has the advantages of strong universality and low computational complexity, and greatly reduces the difficulty and cost of modeling under the premise of ensuring certain accuracy. A 3D Geometry-Based Stochastic Modeling (GBSM) for the entrance scene of railway tunnel in a mountainous area is proposed in reference [

16]. The GBSM is verified by measured data, and the influence of scene boundary, anisotropic scattering degree, and antenna position on channel correlation is analyzed. The existing channel modeling methods, whether based on measurement or theoretical research, seldom discuss the propagation characteristics of radio waves in ultra-high-speed scenarios, especially the time-varying non-stationary characteristics of channels in confined narrow spaces. In tunnel scenarios, narrow space and high mobility of trains lead to reflection through tunnel walls, tunnel wedge diffraction, and scattering in tunnels, which leads to more serious fast fading phenomena, which will produce significant waveguide effects and affect signal propagation. Because of the narrow space and strong mobility of trains in tunnels, radio waves will be reflected by tunnel walls, diffracted by tunnel wedges and scattered in tunnels, resulting in more serious fast fading. All these phenomena cause waveguide effects, which affect signal propagation [

17] and make the existing channel models for high-speed train scenarios [

18] no longer suitable for vacuum tube maglev trains because they do not fully consider such non-stationary characteristics. It is an urgent problem to construct a vacuum channel model which can describe time-varying non-stationary characteristics with both accuracy and efficiency. The research mentioned above has provided valuable insights into channel modeling for tunnels and confined spaces. However, existing cluster-based models and GBSM models typically assume open or relatively low-speed environments, without fully considering the rapid evolution of clusters caused by ultra-high-speeds.

In wireless channel modeling, the concept of cluster is introduced to characterize the typical aggregation characteristics of multipath signals in delay and angle domain. Each cluster corresponds to a set of multipath components. These components have similar characteristics in terms of time delay, and their angles of departure and arrival are also similar. They usually come from the same type of dominant scatterers or reflectors. Cluster modeling is the key to grasp the space–time correlation of channels. Moreover, cluster structure can improve the model’s ability to describe the spatial selective fading characteristics of real channels and reduce the complexity of high-precision channel model effectively. In reference [

19], a low complexity serial one-dimensional search algorithm is proposed to extract the spatial propagation parameters of multipath components in multi-cluster instead of joint maximum likelihood estimation algorithm. A cluster-based time-varying 5G railway (5G-R) channel model is proposed in reference [

20]. The birth and death process of clusters is analyzed through measured data and the typical characteristics of multipath clusters are extracted and analyzed by using four-state Markov chain modeling. Reference [

21] proposes an innovative three-dimensional cluster-based channel model, which distinguishes dynamic clusters from static clusters in vehicle-to-vehicle massive MIMO scenarios and deeply fuses traffic density parameters to the evolutionary algorithm of birth and death process of clusters. Based on the background mentioned above, this paper devotes itself to constructing the scattering cluster dynamic evolution theory mechanism of vacuum pipeline maglev vehicle ground channel. GBSM framework is introduced into the running environment of this special train—the GBSM framework is recommended by international standards bodies for modeling complex time-varying channels, especially in scenarios with defined geometries [

22]—and the probability correlation between the spatial distribution of scatterers and the cluster birth and death process in the pipeline is established. Multipath components are included in wireless channel modeling in cluster form, which takes into account the simplification of geometric level and the actual measurement of channel, controls the complexity of the model, and ensures the accuracy of wireless channel model. In cluster-based time-varying wireless channel modeling methods, accurate identification and trajectory tracking of multipath clusters are necessary prerequisites for building reliable models. This process requires not only instantaneous capture of channel characteristics, but also continuous monitoring of its evolution trend in time dimension, so as to achieve a complete characterization and identification of time-varying channel characteristics. By analyzing the birth and death process of scattering clusters, the evolution mechanism of cluster structure in ultra-high-speed mobile is revealed, and then the dynamic model is fused. The closed expression of channel time autocorrelation function (ACF) is analyzed, and the influence of coupling on channel time-varying characteristics in high-speed state and special environment is described, which provides a certain reference for communication system design. However, existing cluster-based models and GBSM models are not fully suitable for vacuum tube maglev trains due to the extreme Doppler shifts, closed metal pipe structure, and unique scatterer distribution. These models often assume open or low-speed environments and do not account for the rapid cluster evolution caused by ultra-high-speeds. Our work fills this gap by integrating a birth–death process into the GBSM framework, specifically tailored for the vacuum tube maglev scenario. This integration allows us to capture the non-stationary characteristics and dynamic cluster evolution in both time and space domains.

2. Channel Model

The running scene of vacuum pipeline maglev train has obvious propagation environment characteristics. The time-varying characteristics of the channel caused by the narrow and closed pipe structure and the high speed movement of trains cannot be ignored. Although the scatterers distribution in the pipeline presents some spatial regularity, the dynamic evolution of multipath signals is mainly due to the high speed movement of the receiving end. The stochastic modeling method is the best method to characterize this kind of channel because of its adaptability to non-stationary process and low computational complexity. The GBSM model provides an effective way for channel analysis in complex propagation environment by combining geometric constraints and statistical distribution. The method is based on electromagnetic wave propagation mechanism, constrains scatterer distribution through preset geometric structure, and simulates actual propagation path by means of scattering points randomly arranged in space; additionally, it not only retains the intuitiveness of physical propagation mechanism, but also has a flexible statistical modeling ability, can simultaneously characterize spatial distribution characteristics of scatterers and time evolution rules of channels, and is especially suitable for dynamic propagation scenes with deterministic structure constraints such as vacuum pipelines. Based on the above characteristics, GBSM is proposed to analyze the coverage characteristics and fading mechanism of wireless free waves in vacuum pipes.

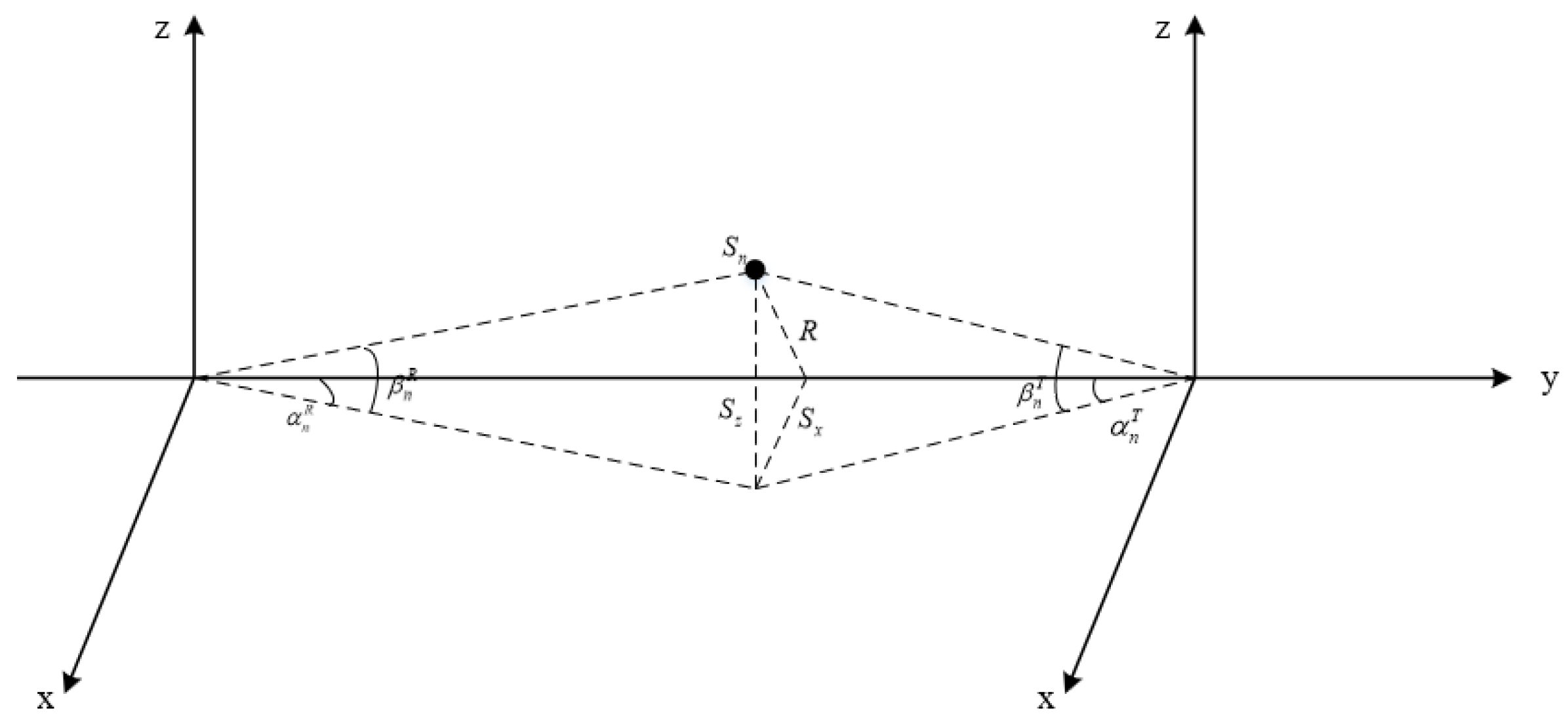

Assuming a 2 × 2 antenna system is adopted, the vacuum pipeline has a symmetrical structure with rotational symmetry in its cross-section. A rectangular coordinate system is established with the central axis of the cylindrical vacuum pipe as the y axis and the running direction of the maglev train as the positive direction.

Figure 1 shows the wireless free wave propagation schematic diagram based on GBSM. Considering the communication link between the lower train and the ground, the transmitting antenna is located at the top of the inner side of the pipeline and the receiving antenna is located on the train, which are, respectively, recorded as

and

. In the 2 × 2 antenna system, the coordinates of the transmitting and receiving antennas are as follows:

The distance between transmitting and receiving antenna array elements are

and

, respectively, the included angle between transmitting and receiving antenna array and train moving direction are

and

, respectively, the initial distance between transmitting and receiving antennas is L, the running speed is v, and the heights of transmitting and receiving antennas are

and

, respectively. The heights

and

are measured from the bottom of the pipe to the respective antennas. During the train operation, the scattering point is located on the inner wall of the cylindrical vacuum pipe. The scattering point is recorded as

; the coordinates of the scattering point satisfy the following formula:

where x and z represent the coordinate components of the scattering point on the x axis and z axis, respectively, in the Cartesian coordinate system, and

R is the radius of vacuum pipe. Using the method of equal areas and the cosine theorem (please refer to

Appendix A for specific derivation), the coordinates expressed in

and

can be derived as follows:

where

and

represent link pitch angle and horizontal angle, respectively.

Under the condition of single-bounce propagation, it is assumed that scattering points act on electromagnetic wave propagation in the form of clusters. Taking the propagation link between to as an example, it contains a line-of-sight (LoS) component and a non-line-of-sight (NLoS) component, which can be expressed as follows:

where

is the direct path and

is the non-direct path, which can be expressed as follows:

where

is the total energy,

is the wavelength,

is the K factor of the link,

represents the number of scattered paths,

is the phase offset and obeys a uniform distribution in

,

represents the distance of the direct link

,

and

represent the distance of the indirect link

and

, respectively, and

and

represent the Doppler shift in the direct component and the indirect component, respectively:

3. Scattering Clusters Birth-Dead Process

In the wireless channel environment of the vacuum tube maglev train, the time-varying characteristics of the channel are mainly caused by the relative position change between the scatterer and the transceiver antenna caused by the train moving at high speed, which will further lead to the dynamic change in the multipath structure of the channel with time. Modeling the wireless channel is essentially modeling and analyzing multipath components. In order to describe the dynamic evolution process of the channel better, this paper introduces an evolutionary algorithm based on the birth and death process of time clusters, considering that the dynamic changes in multipath components in the channel can be reflected by the birth and death of clusters in the case of single-bounce, and the evolution law of clusters and the characteristics of time autocorrelation function can be further revealed by analyzing the distribution probability density of scattering points. This method combines GBSM with the time evolution process, which can describe the channel characteristics of the maglev train in a vacuum pipeline more comprehensively and accurately. The speed of vacuum pipeline high speed maglev train will reach 1000 km/h, and the huge speed difference between the transceiver and the transmitter will lead to more obvious non-stationarity of the wireless channel. The birth and death of scattering clusters in dynamic scenes will affect the non-stationarity of channels. The evolution of clusters is mainly related to the speed by birth and death process. The faster the train moves in time domain, the more obvious the birth and death of clusters become. At the initial time, there will be initial clusters, and the number of initial clusters is denoted by

and calculated as follows:

where

is the formation rate of scattering clusters,

is the death rate of scattering clusters, and the number of clusters at initial time is represented by the formation rate and death rate, which mainly depend on the velocity. As t changes, the number of clusters corresponding to t also changes. The birth and death of clusters depend on the survival probability of time

. Specifically, it can be expressed as follows:

where

is the time-dependent distance constant of cluster time-non-stationary modeling, which affects the time-non-stationary modeling of scattering clusters, and the corresponding typical values include 10 m, 30 m, 50 m, and 100 m [

23]. The survival probability calculated by the above formula changes with time. Correspondingly, the number of clusters changes with time, but it is no longer a fixed value that can be determined at a certain time, but it follows certain statistical characteristics:

In this paper, multipath components are abstracted into a “cluster” structure in wireless channel modeling. Each cluster represents a collection of scattering paths that have similar propagation delay or angular characteristics. Each path in the path set is referenced to the cluster center, plus some random offset, that is, scattering points are clustered around the cluster center and form clusters. Then the method of space geometry constraint can be adopted in the process of generating scattering points in each cluster. First, the number of scattering points contained in each cluster is set to

M. The core mechanism of scattering point generation is based on double offset constraint: add random offset dy in the axial direction (y direction) of the pipeline, and its value range is determined by the maximum grid length, but calculated by physical constraint formula:

Here,

is the minimum value of the Euclidean distance between the cluster center and the transmitting antenna and the receiving antenna, and

is the wavelength. This formula can ensure that scattering points conform to the geometrical optics approximation conditions of electromagnetic wave propagation. The axial offset dy obeys uniform distribution, that is, dy values in the range [−1, 1]. In the angle dimension, the angular offset

corresponds to the arc length offset in the circumferential direction of the pipe. Multiplying the angular offset by the radius

R yields approximately the same linear displacement in the circumferential direction. First calculate the original azimuth of the cluster center:

A random angular offset is then applied. From the perspective of the pipeline’s circumferential symmetry, and based on the characteristic that the physical properties of the pipeline’s inner wall remain consistent in all directions, we set the angular distribution of scattering points on the inner wall to follow a uniform law. This offset is constrained by the pipe radius R and takes a range of values

to form a new azimuth:

The angular offset in Equation (14) is constrained by the pipe radius to ensure that the scattering points remain on the inner wall. This constraint is derived from the arc length formula, where the circumferential displacement is approximately , and the range of is set to to cover the entire circumference while maintaining physical consistency with the cylindrical geometry.

The three-dimensional coordinates of scattering points are finally formed by the strict constraint of double migration and the scattering points satisfy the inner wall surface of the pipeline. The spatial angle characteristics of each scattering point are characterized by two parameters, namely, and , which provide the basic spatial parameters for calculating the subsequent space–time correlation function.

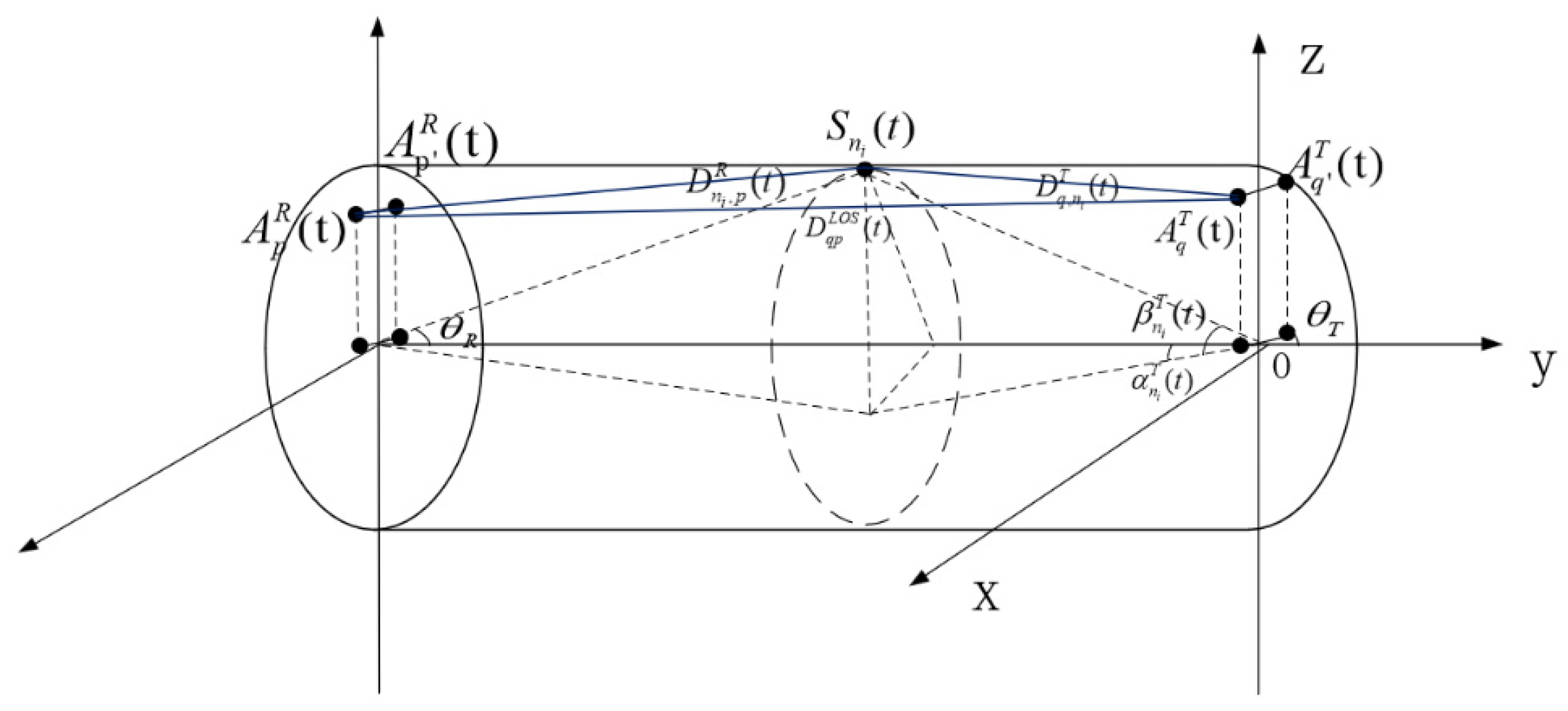

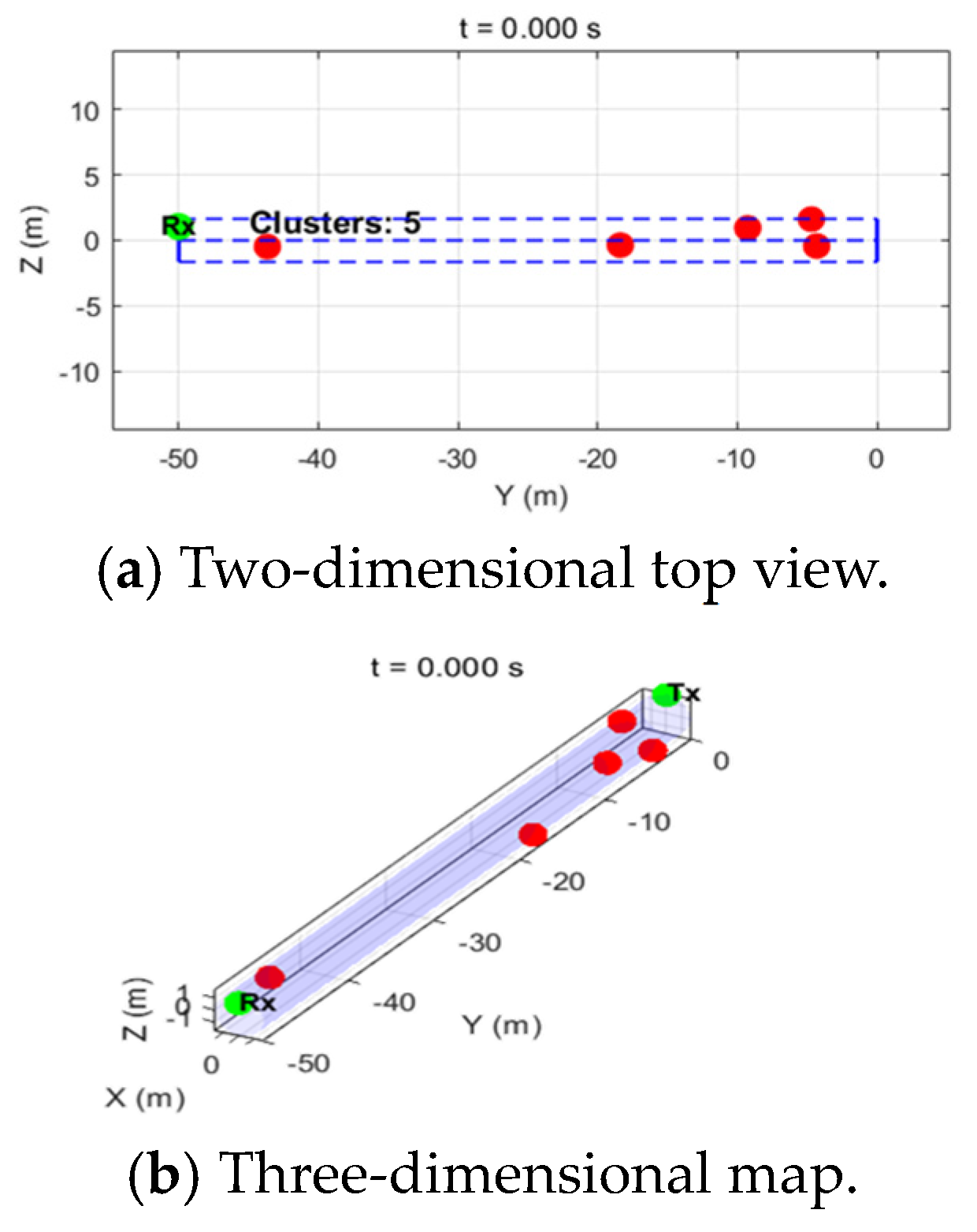

According to the above obtained cluster evolution under non-stationarity and scattering point distribution calculation, propose the birth and death cluster evolution method under the vacuum pipeline maglev train scene; as shown in

Figure 2, the specific steps are as follows:

Cluster initialization: Initialize the scattering cluster on the inner wall of the vacuum pipeline in the initial stage, determine the initial number of scattering clusters according to the ratio of generation rate and death rate, adopt cylindrical coordinate system to realize, and obtain the Cartesian system cluster center coordinates through coordinate transformation:

The initialization, i.e., the cluster distribution at time 0, is accomplished by following a uniform distribution in the axial y direction at [−50, 0] and a uniform distribution in the angular direction at

, immediately generating scattering points based on the center of each cluster and simultaneously recording the current state.

Iterative update: Set the minimum update interval to update the scatter cluster distribution and update the channel state simultaneously. Specifically, information about the channel environment, such as coordinates of the transmitting and receiving end, is updated at each basic time interval, the existence and death of the scattering cluster are determined based on the survival probability of the cluster according to the update condition, and scattering point generation is immediately performed for the updated survival cluster set.

Cycle termination: Repeat step 2 until the expiration time.

Through the GBSM-based channel model combined with the dynamic evolution mechanism of the time cluster birth and death process, the time-varying wireless channel under the vacuum pipeline maglev train scene can be simply and finely modeled and analyzed. This mechanism constructs a complete channel evolution sequence by updating the channel state and birth and death cluster information iteratively after initializing the scattering clusters and scattering points. Based on this channel state sequence, the space–time correlation function theory can be further introduced to quantify the channel statistical characteristics.

5. Simulation

According to the theory and formula above, this section will simulate and analyze the evolution mechanism of birth and death clusters based on GBSM in the vacuum tube maglev train scene. Pipe radius

R = 1.65 m and horizontal distance

L = 50 m at the initial time. In 2013, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and China Railway Group reached a consensus on using the 2.1 GHz frequency band for 5G-R construction. In 2020, the China Railway Group issued the Interim Specification for Railway 5G Dedicated Mobile Communication (5G-R) System Requirements, the Interim Specification for Railway 5G Private Network Business and Function Requirements, and other important standards, and the selection of the 2.1 GHz frequency band was comprehensively demonstrated in terms of frequency transmission characteristics, network carrying capacity, industrial support, and system applicability; therefore,

was selected as the frequency. Additionally,

is obtained from data in reference [

24]. See

Table 1 for all parameter settings of the model.

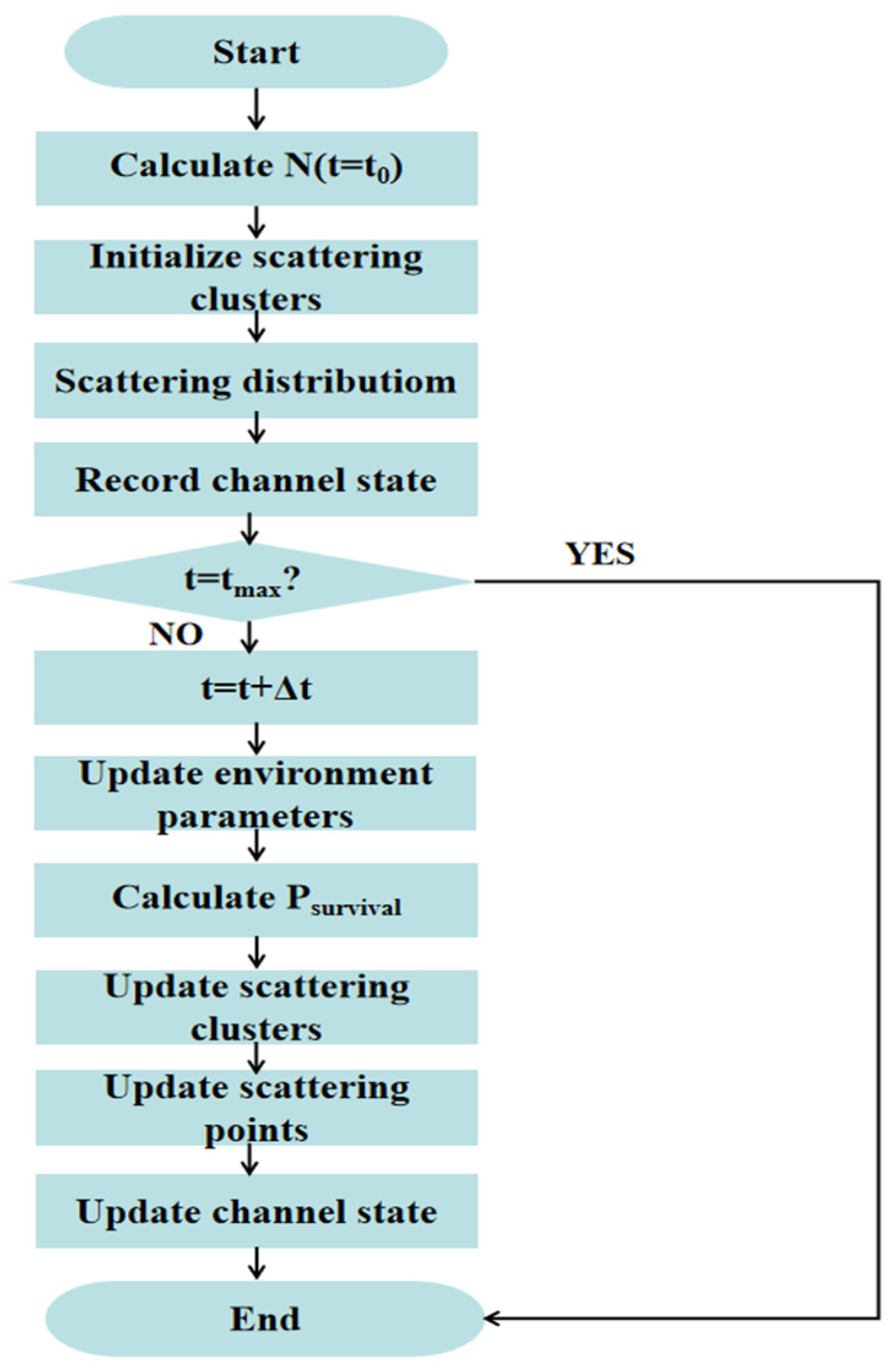

The non-stationarity of channel in time domain is characterized by the birth and death of scattering clusters, that is, the evolution of clusters in time coordinate is discussed. Characterizing the evolution state of a cluster is the survival and death of the cluster under a certain probability in the operating environment, that is, whether it can be observed.

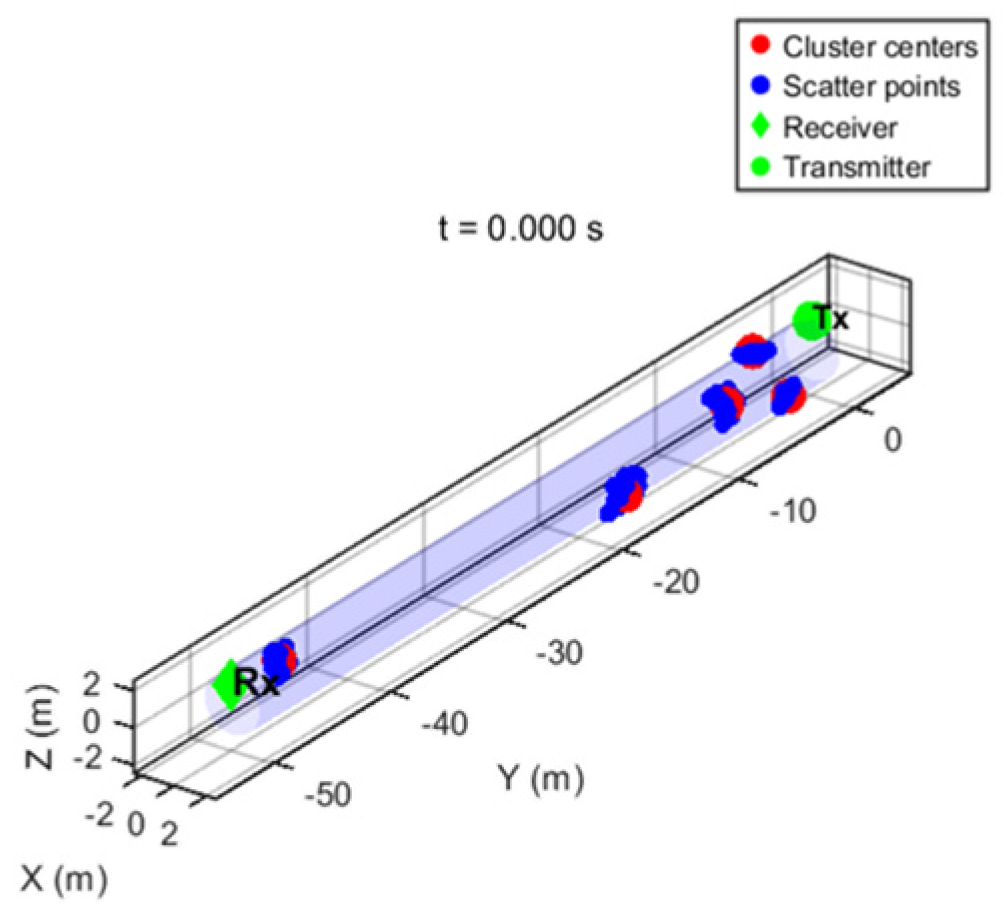

Firstly, the initialization of scattering clusters is performed. The model assumes that scatterers are distributed independently in two-dimensional uniform distribution in the pipe section, and the scattering area is a cylindrical pipe area with radius R within the horizontal distance from the transmitting and receiving antenna. The number of initial clusters is obtained according to the values of generation rate

and mortality rate

at the initial time

, and the distribution of clusters at the initial time is obtained as shown in the

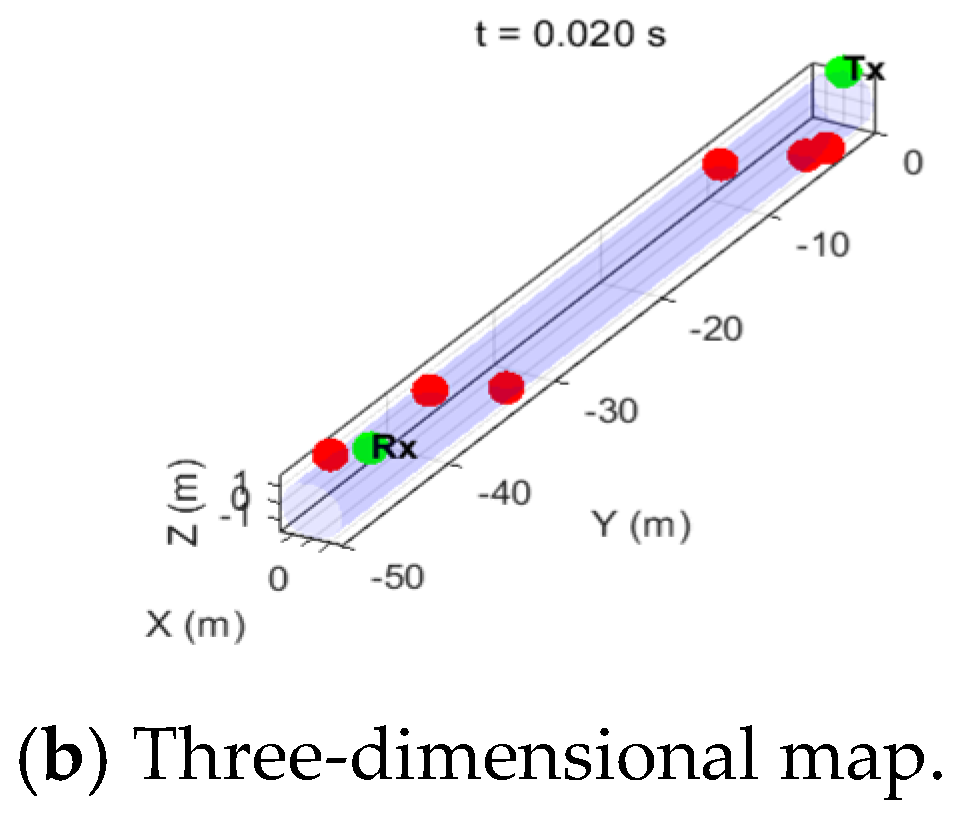

Figure 3, wherein (a) is a two-dimensional plan view, and (b) is a three-dimensional stereoscopic view.

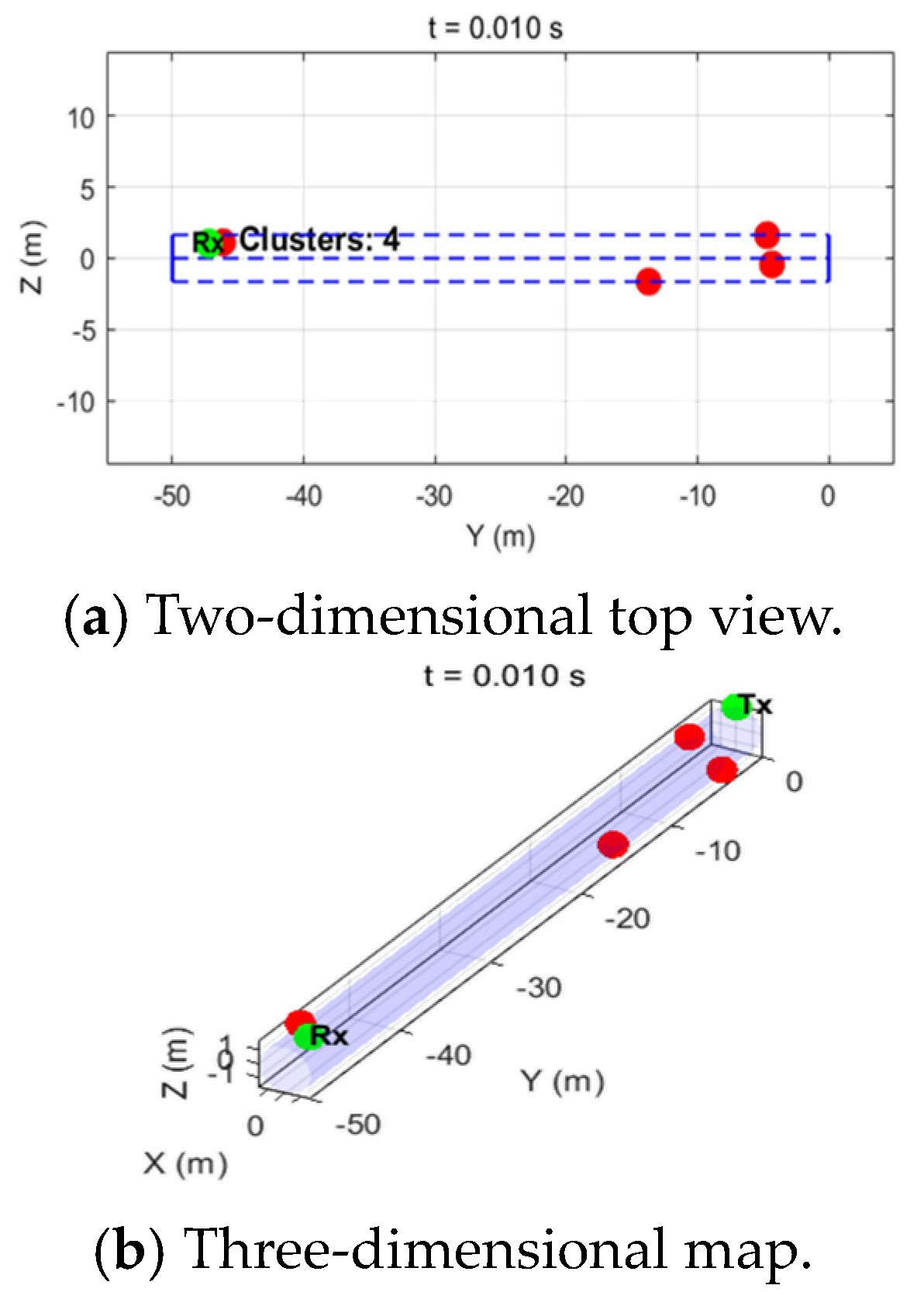

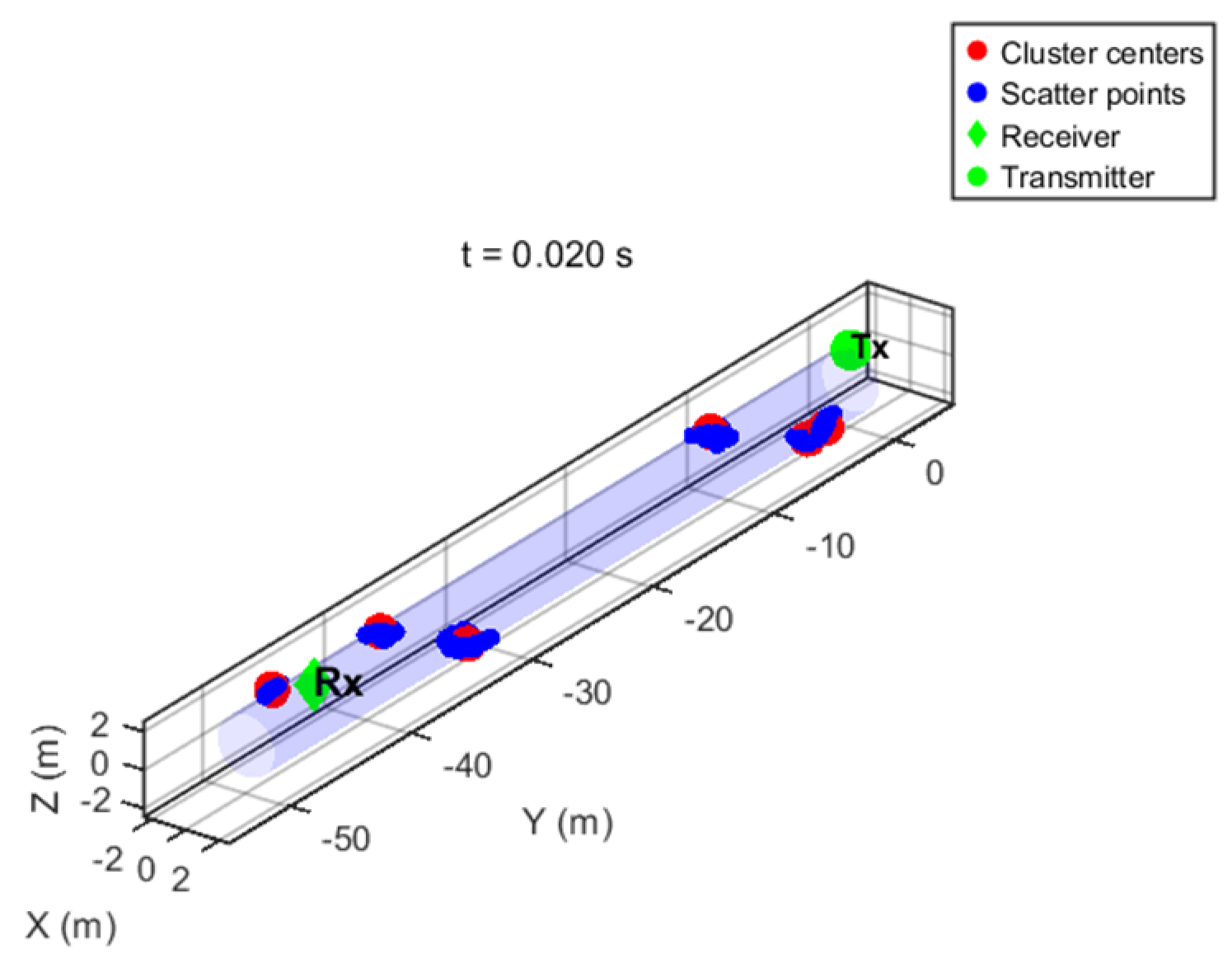

The intra-cluster scattering at the initial time is generated by double offset constraint, and the channel state at the current time is recorded as shown in

Figure 4.

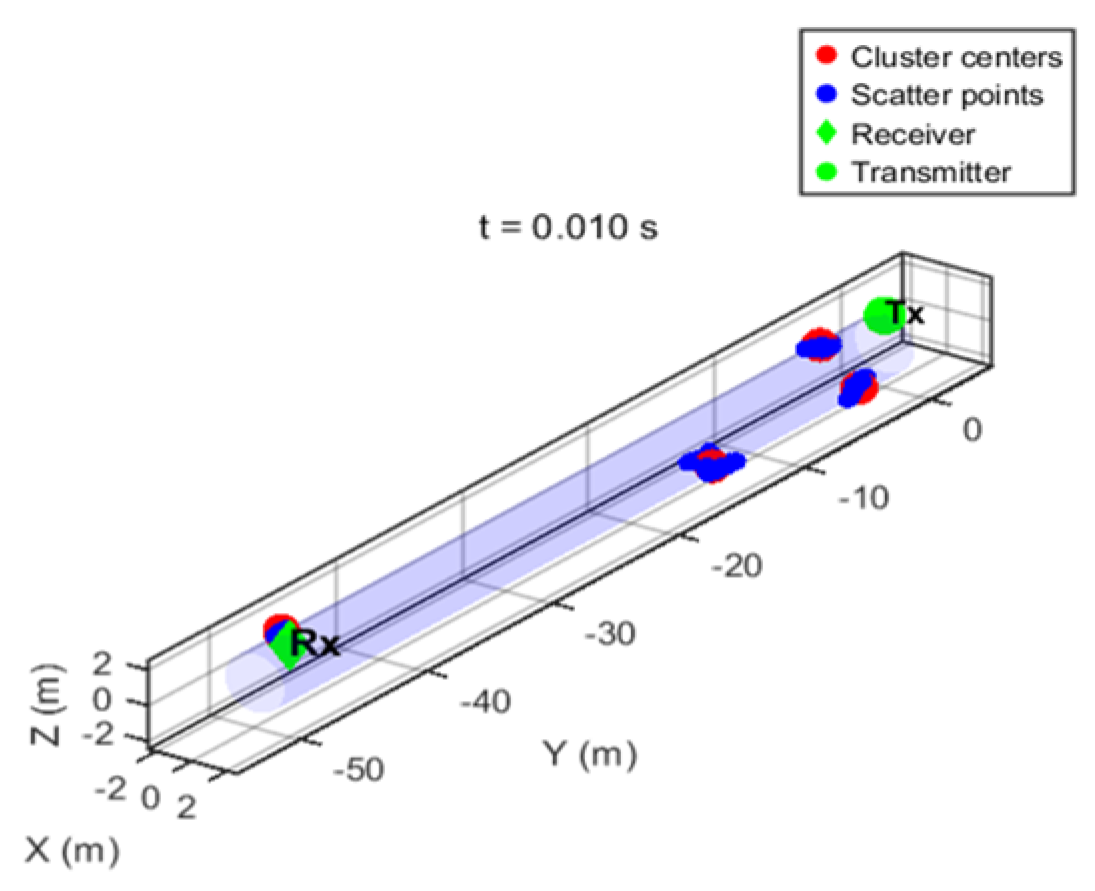

When the train moves along the axial direction of the pipeline at the speed v, the relative position of the scatterer and the antenna changes with time, resulting in dynamic adjustment of the effective scattering area. Select the time

to update the environmental information at the time

. Based on the statistical expectation of the number of scattering clusters, the number is updated and the position update is still updated with uniform distribution so as to obtain the distribution of scattering clusters at this time as shown in the figure, wherein (a) is a two-dimensional plan view, and (b) is a three-dimensional stereoscopic view. The scatter points in that cluster at time

are generated through double offset constraint, and the channel state is recorded as shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

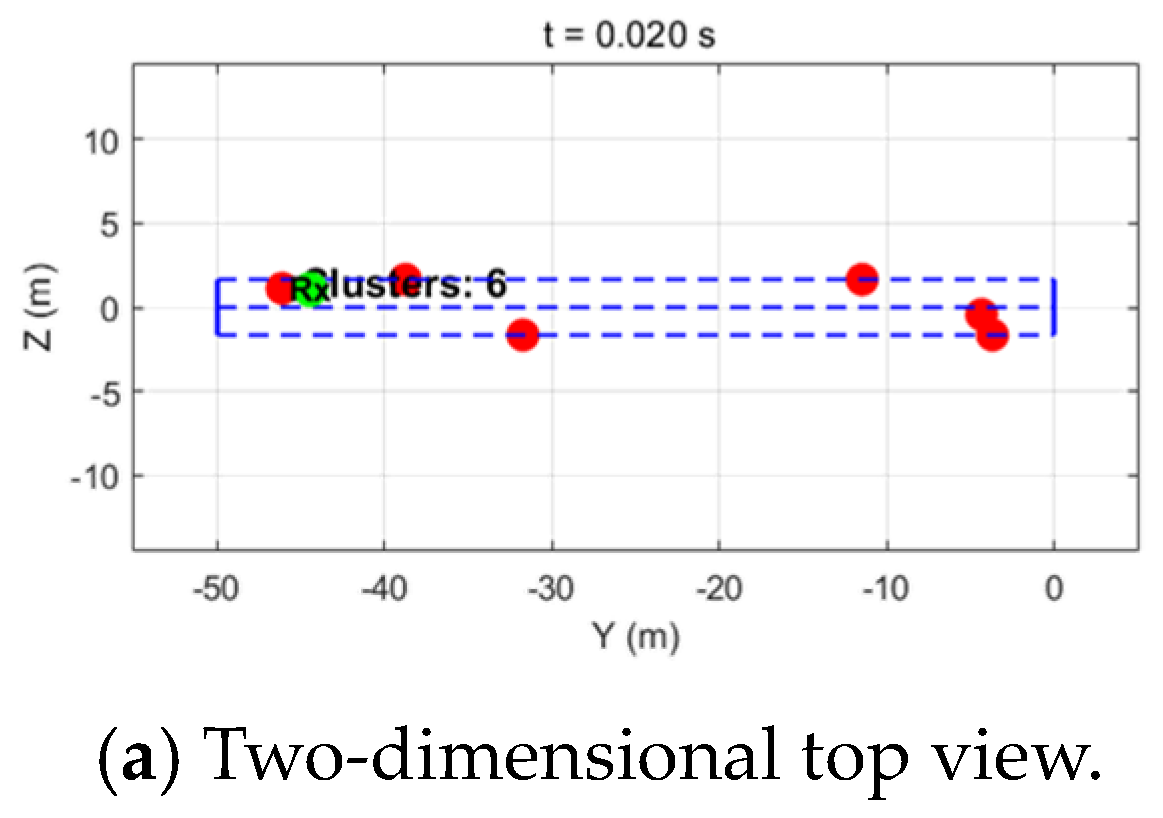

is selected to update environmental information such as the position of the transceiver antenna at the current time

. The corresponding number update and position update are still performed to obtain the distribution of scattering clusters at this time point as shown in the

Figure 7, wherein (a) is a two-dimensional plan view, and (b) is a three-dimensional stereoscopic view. The scatter point distribution in the cluster at the current time is shown in the figure below. The current channel state is recordedas shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

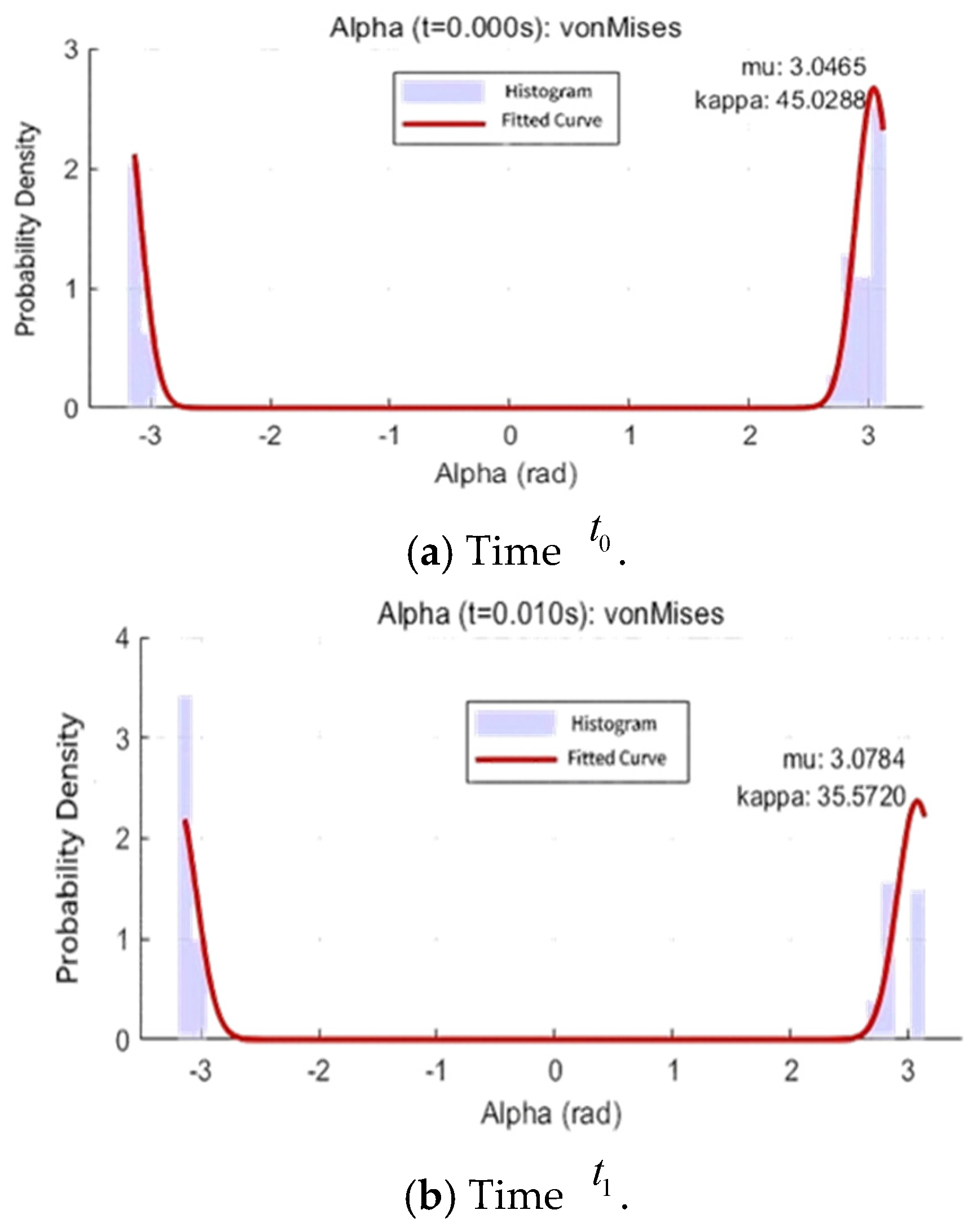

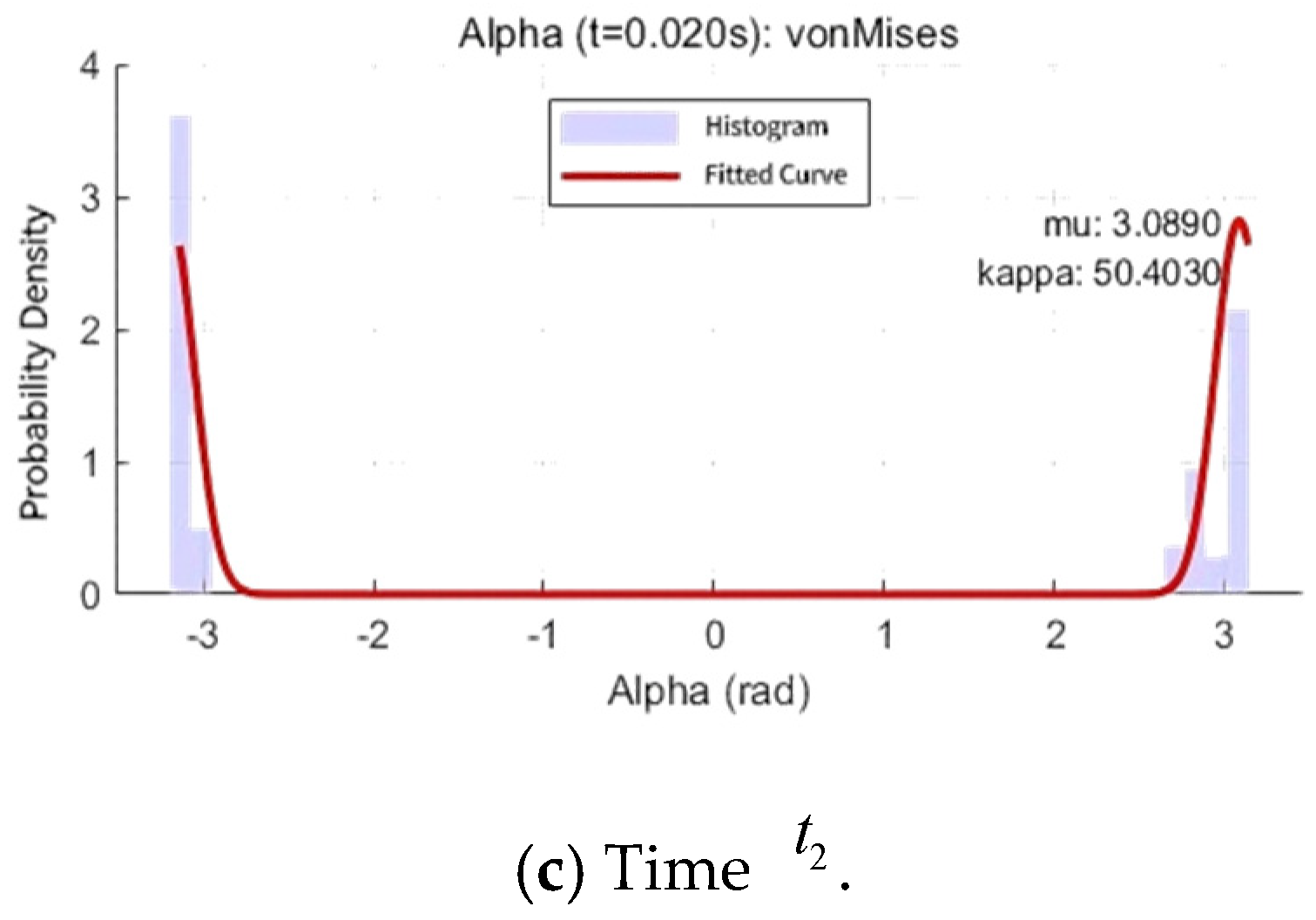

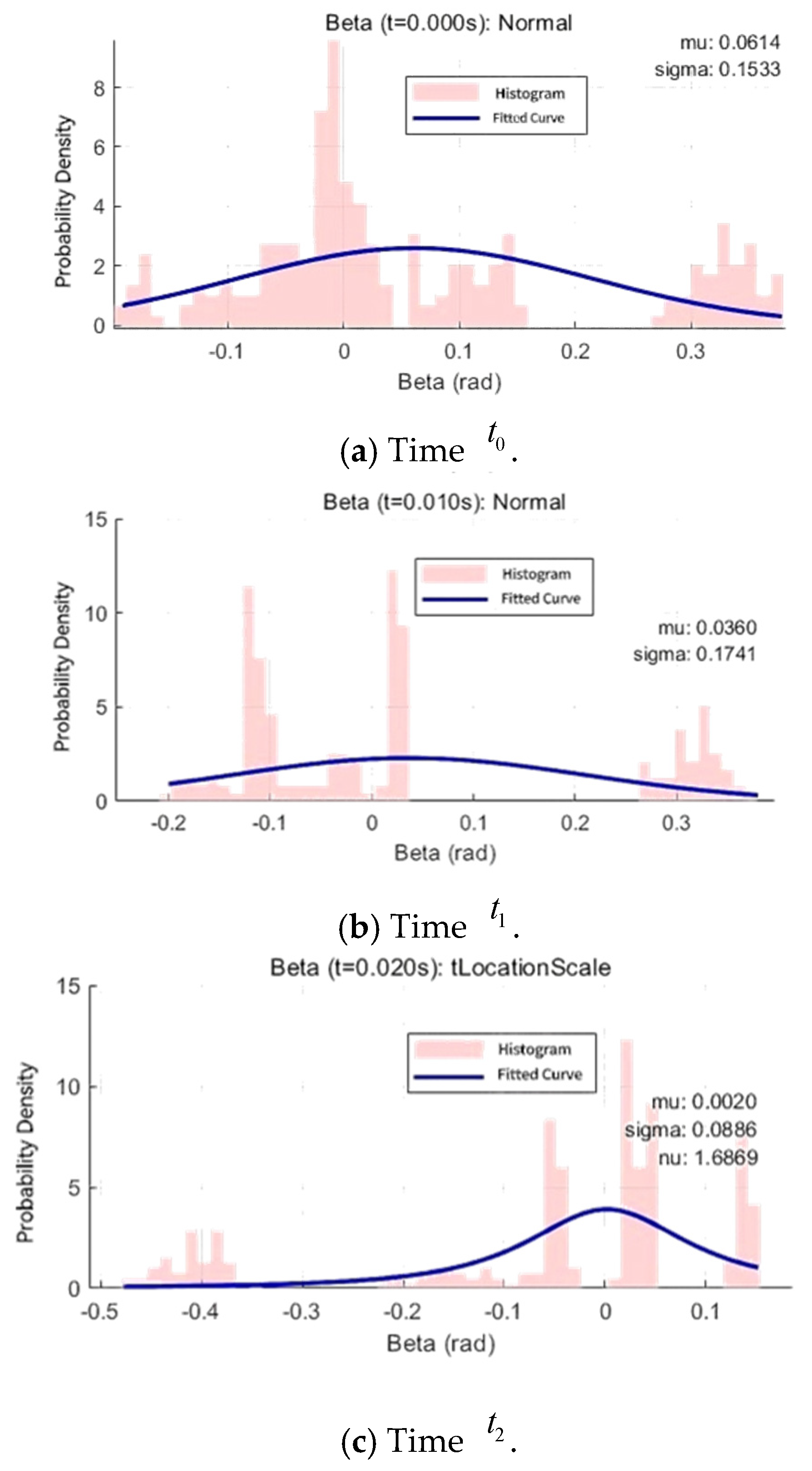

The angles are statistically analyzed and recorded as above at the three times, and statistical fitting for

and

is made. The fitting results are shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

By fitting

, it is made clear that the von Mises distribution is obeyed three times, and the probability density function is as follows:

where at time

,

, at time

,

, and at time

,

. The initial

distribution is centered around 45°, indicating that the pitch angle of the scattering cluster is relatively stable at the initial time, which is mainly constrained by the pipe geometry. The high

value indicates that the pitch angle of the scattering point changes little, and the channel presents strong spatial consistency. At

, the average direction of α decreases from 45° to 35°, indicating that the pitch angle of the scattering cluster moves downward as the train moves. This may be due to the change in the relative height of the receiving antenna and the scattering points on the pipe wall caused by the movement of the train, which makes the multipath component more horizontal, and the κ value slightly increases, indicating that the pitch angle distribution is slightly more concentrated, but the overall change is small. At time

, the average direction of α rises to 50.4°, and the value of

is close to

, indicating that the pitch angle distribution returns to a centralized but direction shifted. This may be because the train moves to different sections of the pipeline, the pipeline bends, or local structural changes cause the elevation angle of the scattering point to move upward. The channel is characterized by periodic spatial variation.

By fitting

,

and

obey normal distribution. The probability density function is as follows:

The parameter of

is represented as

. Time

obeys the T Location-Scale distribution, and the probability density function is as follows:

where

. The probability fitting parameters of the three moments are listed in

Table 2 and

Table 3. The initial

distribution is very concentrated, indicating that the horizontal angle deviation is very small, and the scattering points are mainly distributed along the axial direction of the pipeline. This reflects that the channel is dominated by the pipeline wave guide effect at the initial time, and the angular diffusion of multipath components is limited. At time

, the standard deviation of

increases significantly, indicating that the horizontal angular diffusion intensifies. This is due to the introduction of Doppler spread and scattering cluster birth and death process into the high-speed train movement, resulting in more dispersed angle distribution. The channel non-stationarity begins to appear, and the randomness of multipath components in the horizontal direction increases. At

, the distribution changes from normal to heavy-tailed T distribution, indicating that the probability of extreme value of horizontal angle increases. This reflects the fast birth and death process of scattering clusters under high speed movement: the survival time of remote clusters is longer, but the angle changes sharply; a short life cycle of close cluster leads to abnormal value of angle distribution. The channel non-stationarity intensifies, and the time correlation further decreases.

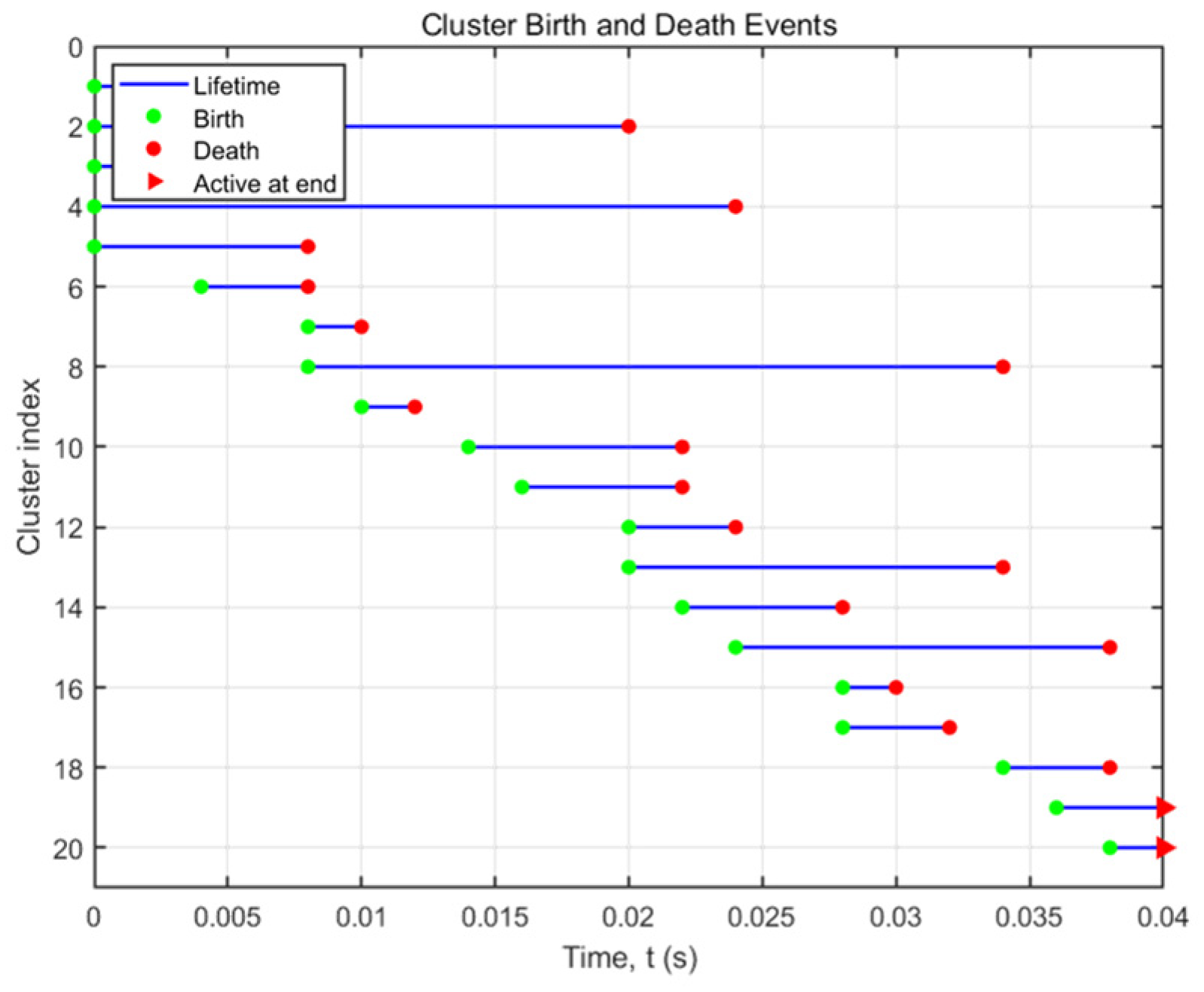

Analyzing the change in scattering clusters in the initial 0.04 s, we can clearly see the rule of the number of scattering clusters changing with time from

Figure 11: the number of active clusters is not much at the beginning, and gradually increases with time. The simulation results show the appearance and disappearance of each cluster at a specific time point, and the horizontal line segments with different lengths obviously reflect the difference in existence time of each cluster. These birth and death events are distributed unevenly on the timeline, which reflects the temporal non-stationarity of the channel. And most of the clusters generated near the train have a shorter life cycle. This is because high-speed moving trains will quickly pass through local areas of these clusters, reducing the survival probability, and close-distance clusters are more likely to exceed the relevant distance range due to the rapid movement of trains. The long lifetime of the distant cluster is due to the small radial velocity component of the distant cluster relative to the receiver. At the same time, the pipe structure also restricts the spatial distribution of clusters to some extent, and the lateral cluster position changes slowly. By simulating the evolution of scattering clusters, we can not only know the state of clusters at the current time, but can also provide a coherent basis for the simulation of correlation function.

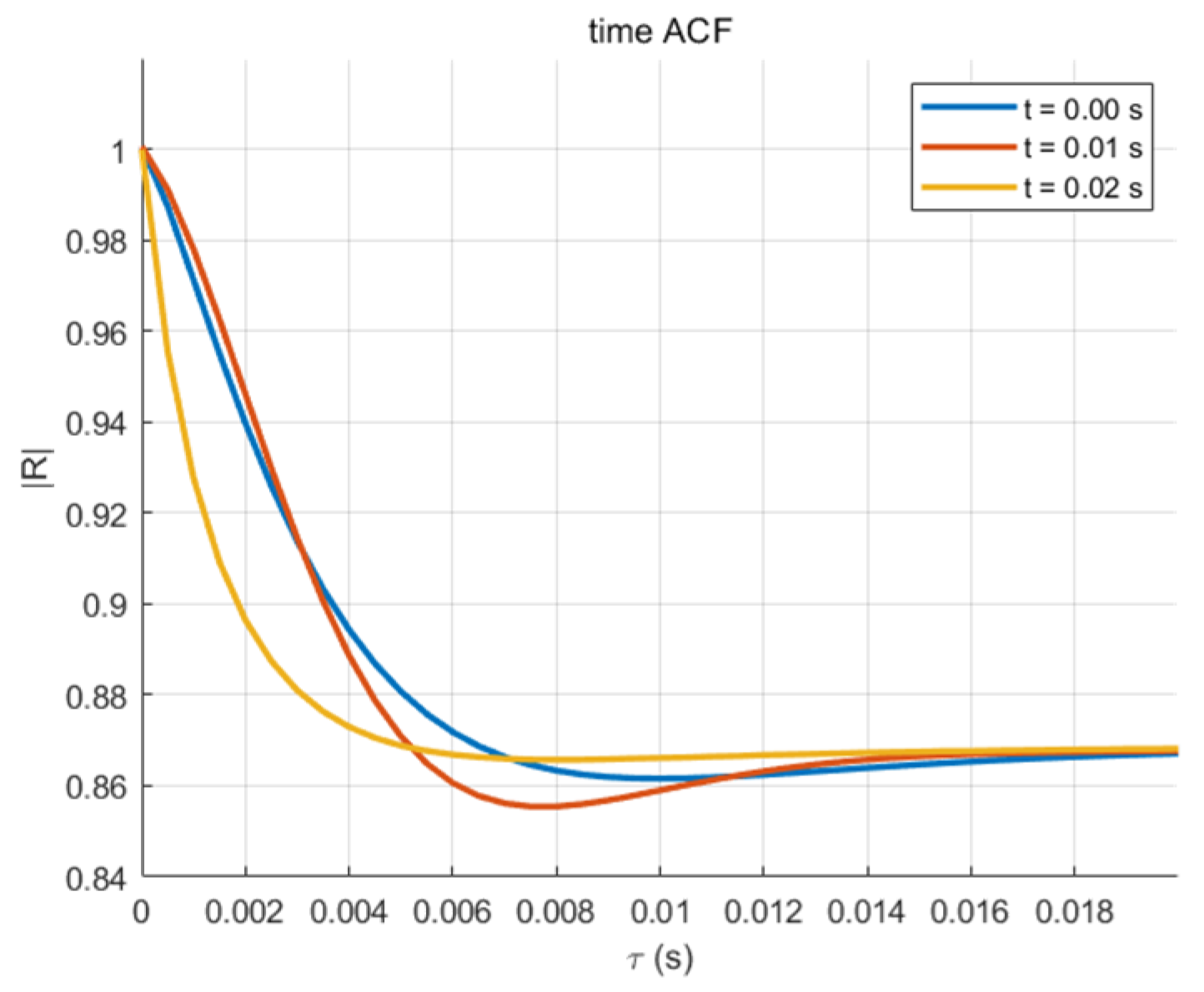

After the evolution characterization of scattering clusters in time domain is obtained, the simulation of time ACF is emphasized.

Figure 12 shows time ACF curves for t = 0 s, t = 0.01 s, and t = 0.02 s. A comparative analysis of these curves reveals the dynamic impact of cluster evolution on channel coherence. ACF of the proposed model is different at different time points under the condition of high speed of maglev train: The initial rapid attenuation of ACF across all time instances is primarily driven by the fast birth and death process of scattering clusters and the significant Doppler spread induced by the ultra-high-speed. Correlation attenuation is fast when new scattering clusters appear suddenly under the condition of a high speed of train; conversely, scattering clusters tend to be stable, time-variation is weak, and correlation attenuation is slow. Notably, the ACF at t = 0.02 s exhibits the slowest initial decay, suggesting a period of relative cluster stability at that specific moment. Although the CIR correlation decreases with the increase in delay, it is easy to see from the figure that the correlation tends to stabilize at 0.861 with the delay increasing. This indicates that no matter how the train moves, there is always a highly correlated steady-state core component in the channel. This is probably due to the inherent and static strong reflector of the pipe itself, such as the waveguide effect produced by parallel pipe walls. The time ACF stability value of the model in this paper is significantly higher than that in [

21], indicating that the channel core is more stable due to the waveguide effect in the enclosed pipe, while [

21] has lower correlation due to the open dynamic V2V environment. Compared with [

25], the model in this paper introduces dynamic cluster evolution, which can capture the transient characteristics of multipath components under ultra-high-speed. The static model treats the scattering environment as uniform and time-invariant, thereby averaging the contributions of all possible multipath components, including transient components under high-speed conditions. In contrast, our model’s integrated birth–death process dynamically accounts for the disappearance of short-lived, rapidly evolving scattering clusters caused by the train’s extreme velocity. This mechanism allows the model to highlight and more accurately quantify the persistent channel core sustained by the waveguide effect of the enclosed metal pipe. This persistent correlation core, maintained by the guiding structure of the pipe, has critical implications for system design: it suggests that a baseline level of channel predictability exists, which could be leveraged by robust modulation schemes or tracking algorithms to mitigate the otherwise severe non-stationarity.

6. Conclusions

This article proposes a dynamic evolutionary modeling method based on geometric random models and integrated scattering cluster birth and death processes in symmetrical cylindrical pipelines to solve the non-stationary modeling problem of the wireless channel between the maglev train and the ground in vacuum pipelines under the dual challenges of high-speed operation and closed pipeline environments. The core of this study is to dynamically correlate the train speed with the update rate of scattering clusters through the survival probability of clusters, thereby accurately characterizing the generation and disappearance of multipath components over time within the GBSM framework.

Theoretical derivation and simulation analysis show that the time autocorrelation function of the channel stabilizes at about 0.861 after the delay increases, revealing that under strong non-stationarity, the pipe waveguide effect can still provide a stable channel core component. At the same time, the life and death evolution diagram of clusters intuitively shows that the life cycle of near vehicle clusters is extremely short. This discovery directly quantifies the upper limit of channel coherence time and imposes strict requirements on the system pilot density and channel estimation algorithm for millisecond-level fast tracking.

In summary, the model established in this article not only systematically reveals the dynamic evolution laws of the channel in the time and space domains in the vacuum pipeline maglev scenario but also provides specific guidance for communication system design: the system needs to configure high-density pilots to cope with rapid channel changes, and predictive algorithms can be developed using the steady-state characteristics of ACF to improve performance. Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations that point to future research directions. First, the computational complexity of iteratively updating clusters and scattering points may pose challenges for real-time channel simulators, and optimization in this regard is needed. Second, a comprehensive sensitivity analysis of key parameters will be performed to better understand their impact and guide parameter selection. Finally, a quantitative performance comparison with existing channel models was not conducted due to implementation challenges specific to the vacuum tube scenario; such a comparison remains an important future task. Future work will focus on these aspects.