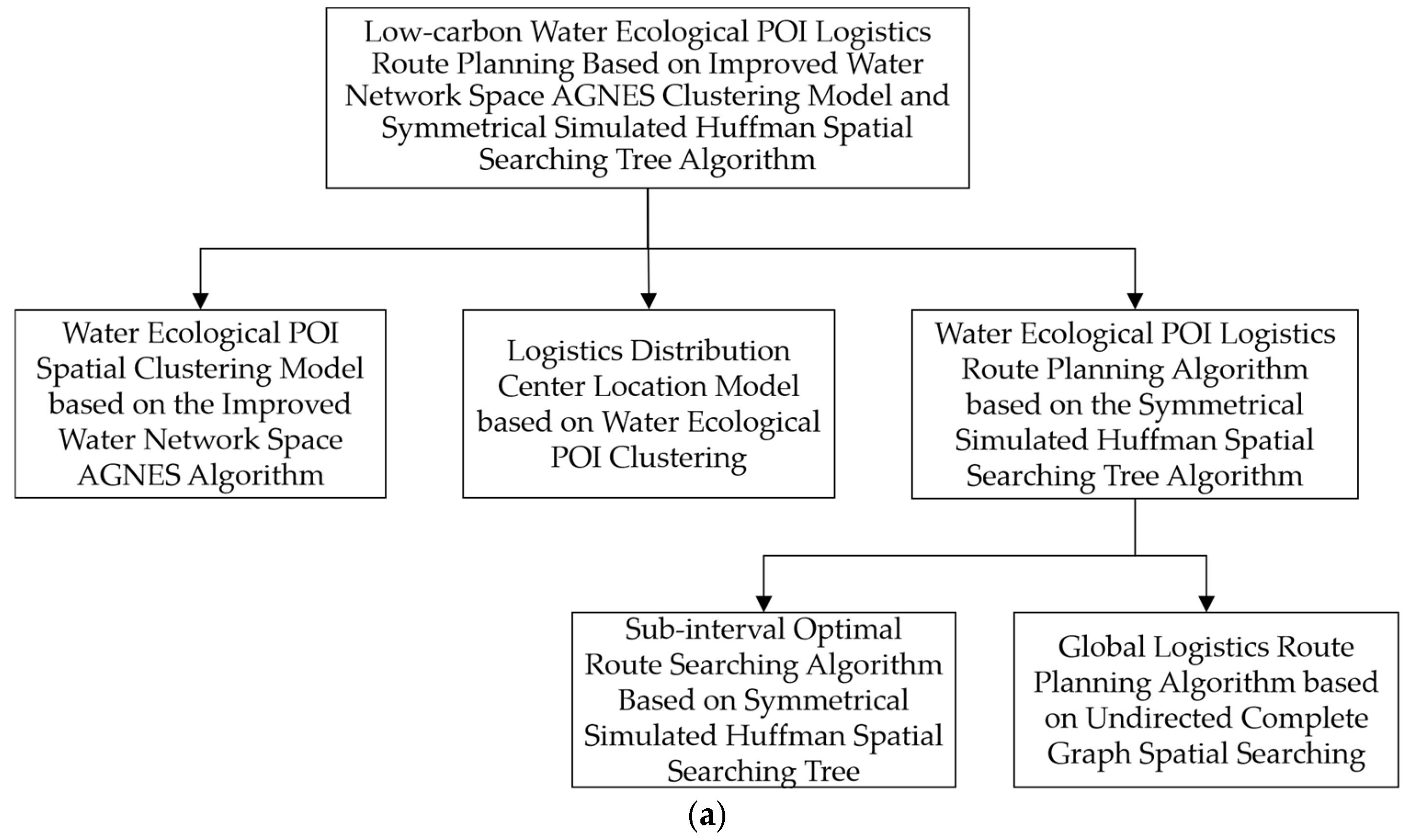

In response to the spatial distribution features of the water ecological POIs and the demands for the logistics route planning, we first construct the clustering relationship model between the water ecological POIs and the water network buffer zones. Secondly, we establish the spatial relationship model between the urban distribution centers and water ecological POIs in each cluster, and search for the optimal distribution center location as the starting and ending points of logistics routes. Based on this, we construct a multi-level logistics route algorithm based on the symmetrical simulated Huffman spatial searching tree algorithm to search for the optimal routes in the logistics sub-intervals and logistics intervals.

3.1. Water Ecological POI Spatial Clustering Model Based on Improved Water Network Space AGNES Algorithm

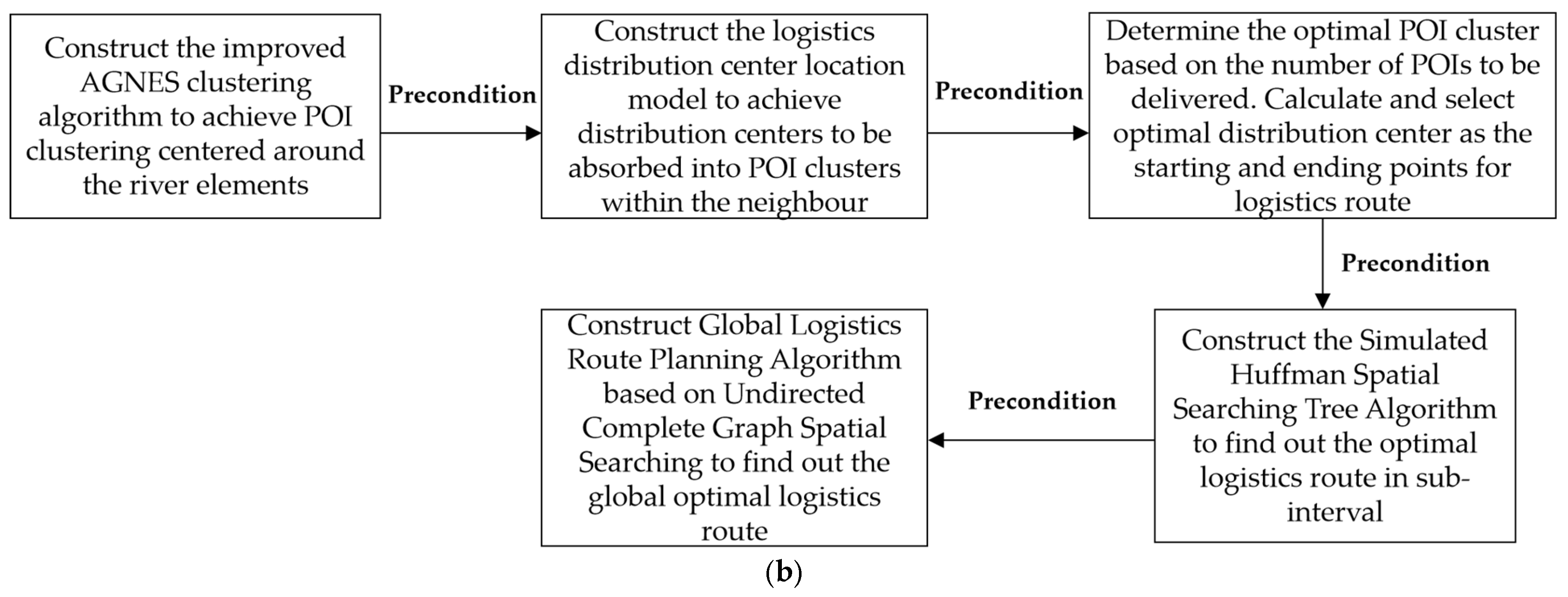

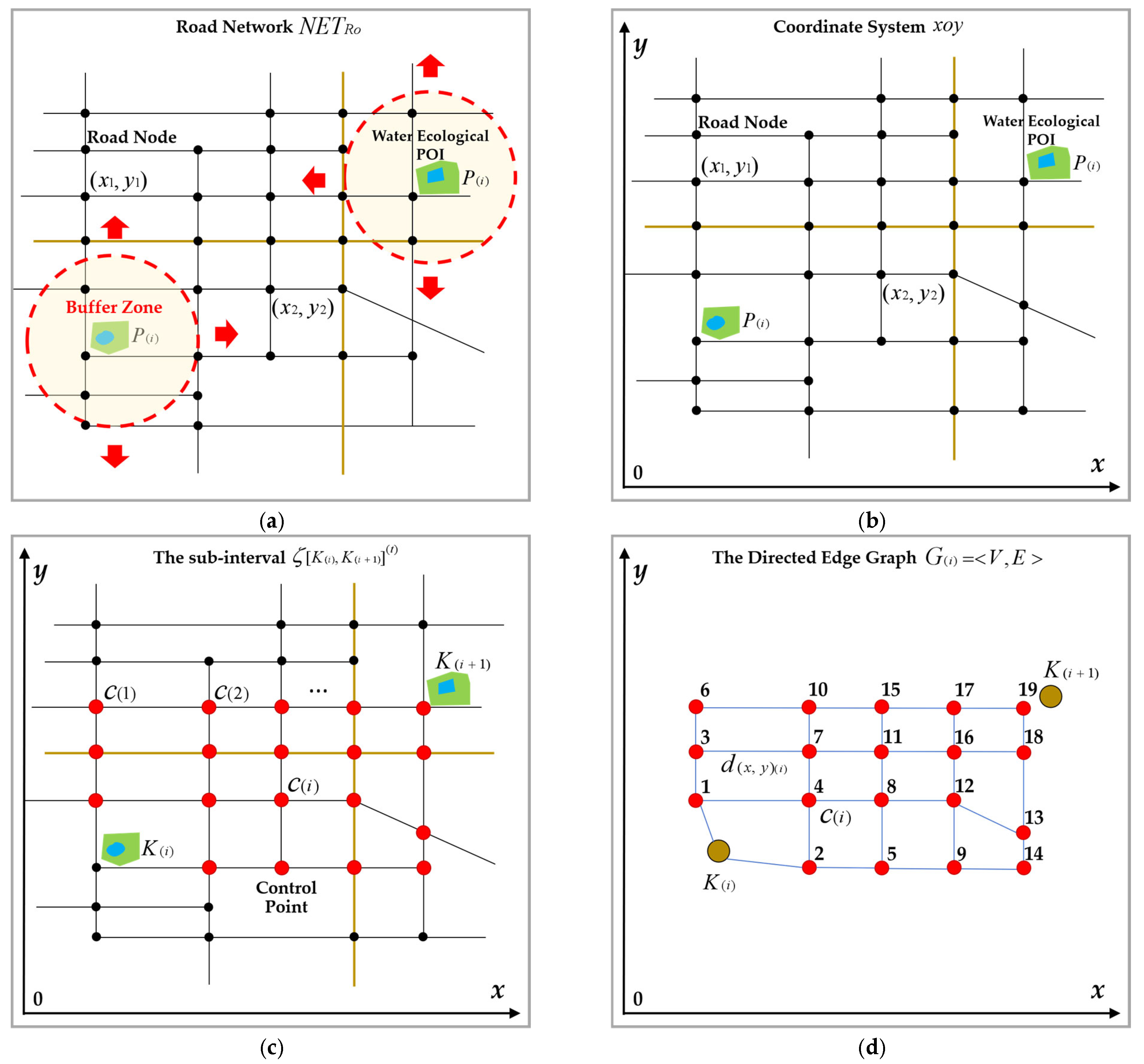

Water ecological POIs are distributed in urban geospatial environments and have geographic spatial attributes such as geographic coordinates, spatial distance, etc. In tourist cities dominated by water ecological POIs and water network rivers, the water network rivers form the natural network system and are usually represented by linear symbols on maps [

23,

24]. For the water network rivers represented by linear symbols, we selected those with important tourism value and basic water ecological architecture from the urban geospatial environment, and projected them onto the coordinate system to form the meta-structure of water ecological POI clustering. By establishing the urban spatial road network, we constructed the control point set for the main water network meta-structure, and then used the control point set to construct a buffer zone for the main water network meta-structure. Then, the improved AGNES clustering algorithm was established to achieve the spatial relationship between the water ecological POIs and control point set, thereby realizing the water ecological POI clustering based on the main water network meta-structure.

Definition 1.

Establish a coordinate system covering all water ecological POIs and water network in the water tourism city. The coordinate system is defined as the water ecological POI clustering coordinate system, denoted as . The water ecological POI for material distribution is defined as a water ecological POI element. If the number of element in the city is , then , . The geographic coordinates of in are denoted as and .

Definition 2.

The selected main roads in the water tourism city are projected onto to form a road network, denoted as . The selected main water network channels in the water tourism city are projected onto to form the main water network meta-structure, denoted as . Project onto and extract number of rivers, and each river is denoted as a dataset element , , . The dataset consisting of the number of extracted rivers is defined as the river projection dataset. The is a subset of .

Definition 3.

The water ecological POI buffer zone is formed by the

, which is extended to form the POI cluster , , , where is the number of the clusters. The point set formed by the intersection of element and the is defined as the cluster control point set, denoted as . Set the number of control points in of as , and the number of control points form the structure of , and . Note the element of as , as No. control point of , , . The coordinates of are and .

Definition 4.

Construct a

dimension matrix to store the set of control points in of the dataset . The rows represent the elements and the columns represent the No. control point . When the number of water ecological POIs form number of clusters , a dimension matrix is constructed to store each cluster POI. The rows represent clusters and the columns represent the No. POI element of the cluster, , . Formulas (1) and (2) represent the matrix , and Formula (3) is the matrix .

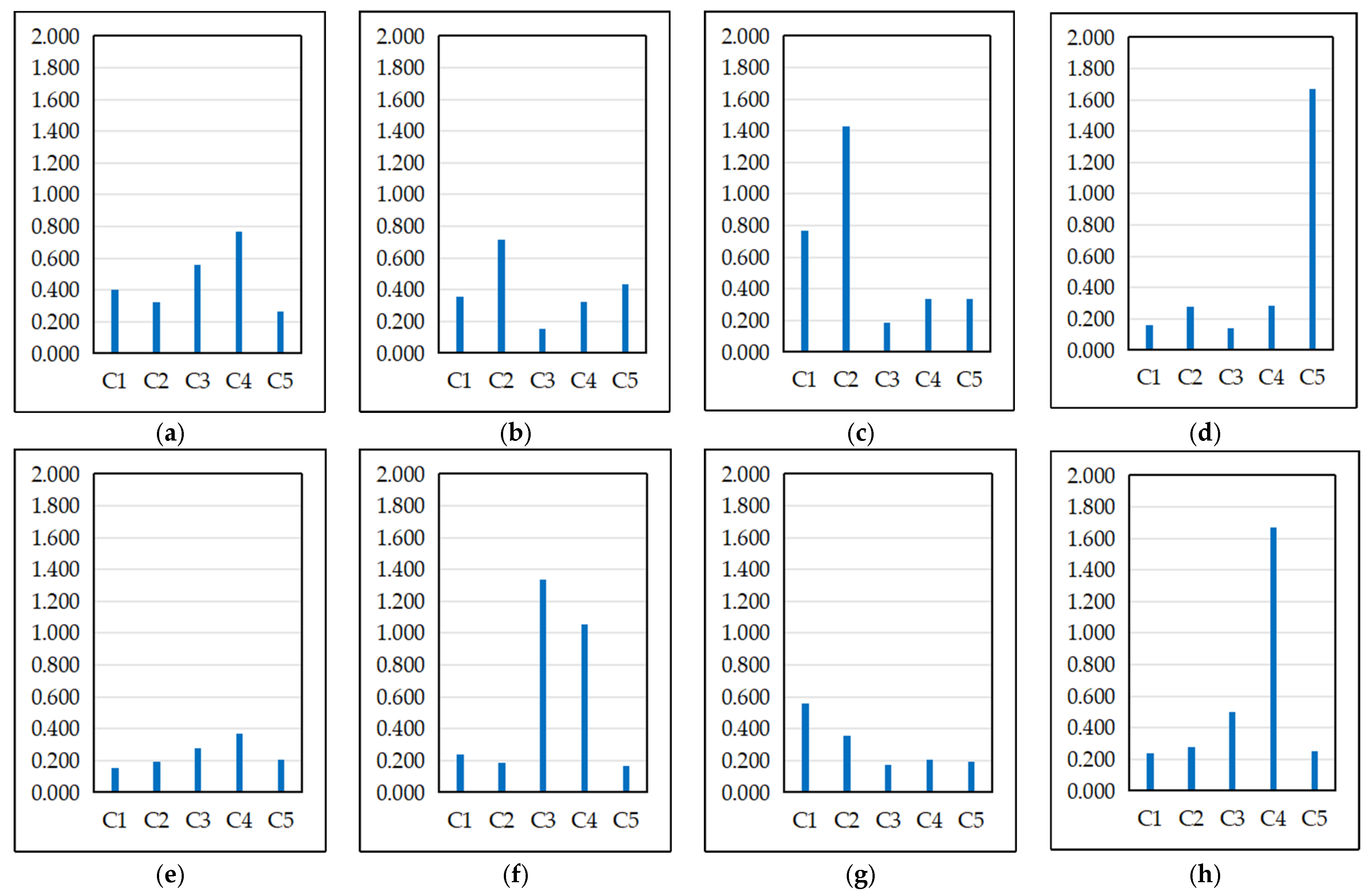

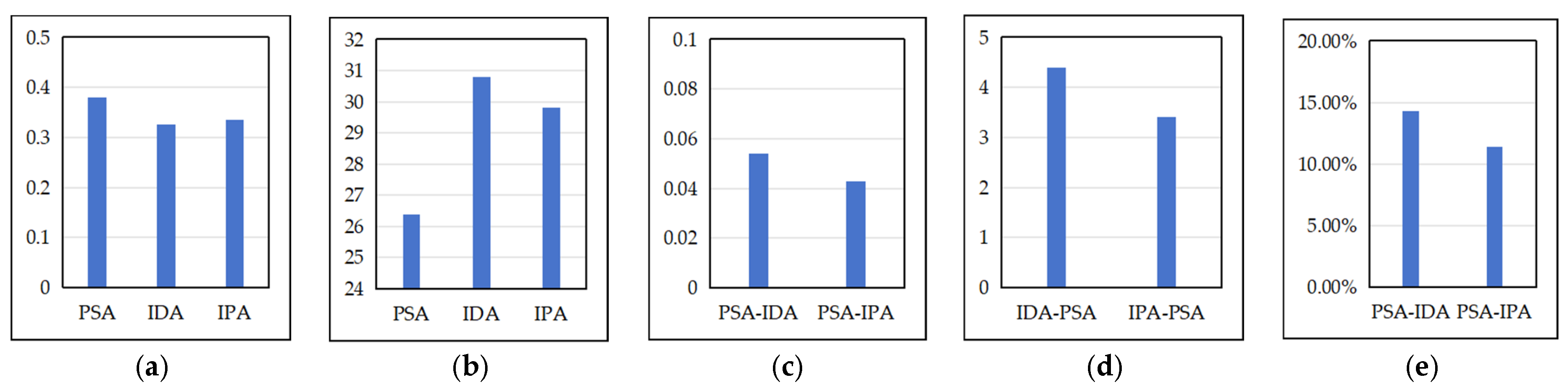

According to the definition,

Figure 2 shows the generating process of the

,

, dataset

and elements

, cluster

buffer zones, and control point sets

by the urban water network channels and main roads in the coordinate system

. Among them,

Figure 2a shows the constructed main water network meta-structure (

),

Figure 2b shows the constructed main road network (

),

Figure 2c shows the constructed river projection dataset

,

Figure 2d shows the constructed water network cluster

and the buffer zone,

Figure 2e shows the overlay model of

and

, and

Figure 2f shows the constructed cluster control point set

.

The objective function for constructing the cluster is defined as , and its calculating criterion is the spatial accessibility of to . The spatial accessibility model is constructed as in the Formula (4), and is the dimensionality reduction parameter. The definition of value is as follows:

(1) If the spatial distance between and meets , ;

(2) If the spatial distance between and meets , ;

(3) If the spatial distance

between

and

meets

,

; and so forth.

Based on Formula (4), construct the function as the Formulas (5) and (6), and is the dimensionality reduction parameter. The definition of value is as follows:

(1) If the reciprocal of meets , ;

(2) If the reciprocal of meets , ;

(3) If the reciprocal of

meets

,

; and so forth.

Based on the set and the dimension of , a complete binary tree with number of nodes is constructed, and it is defined as the complete binary tree for the water ecological POI clustering. The tree node stores the function value , and its structure satisfies the following conditions:

(1) The height of the tree is , and the parent node level is 0. Therefore, all the child nodes are at No. level, , , and for any node , it can contain at most 2 child nodes and at least no child nodes;

(2) When , the No. layer contains number of nodes;

(3) If there are child nodes in the No. layer, all the child nodes are concentrated on the leftmost side;

(4) For any No. layer node and No. layer node, satisfy ;

(5) For any No. layer, satisfy ;

(6) If a node contains only one child node, it must satisfy the condition of node not containing any child node, .

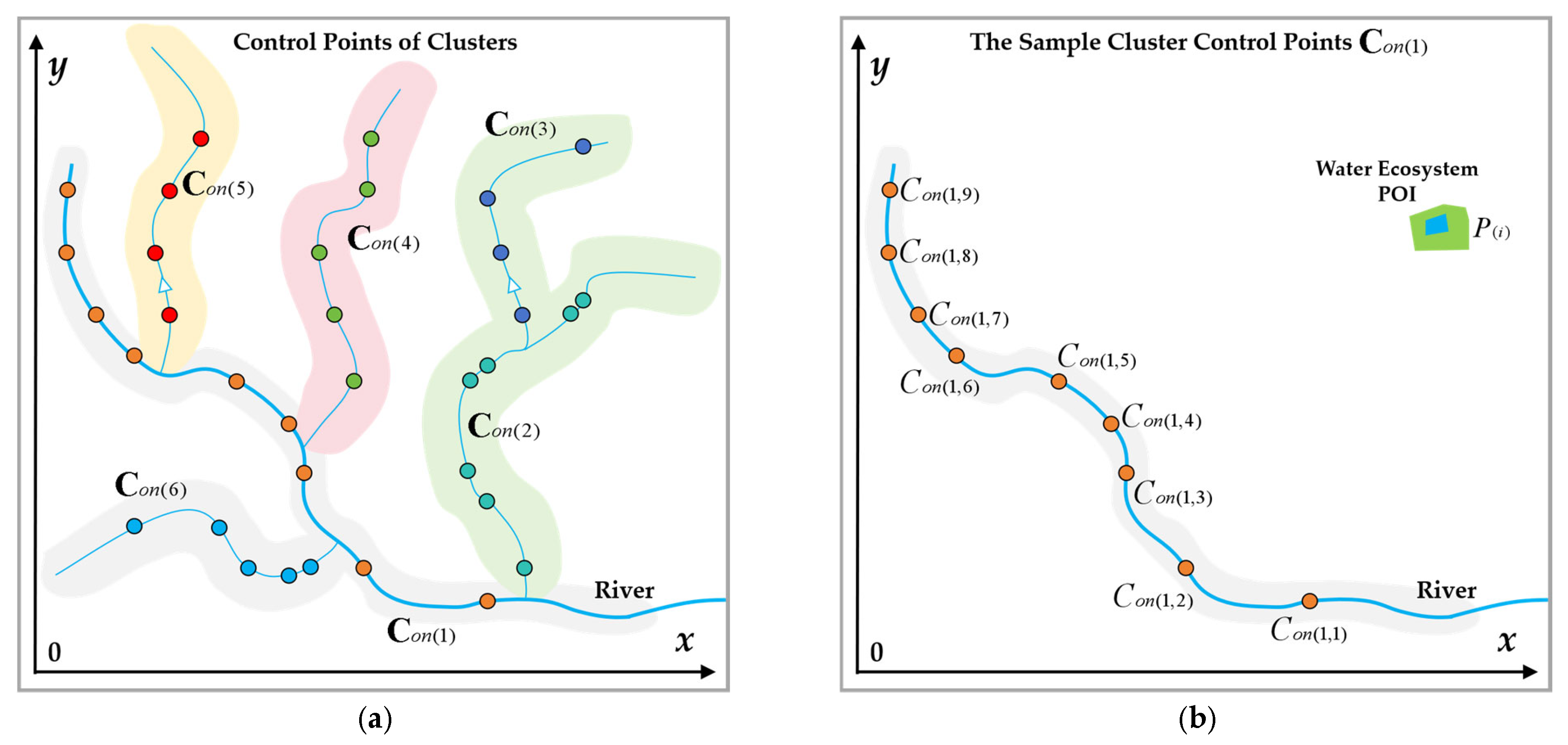

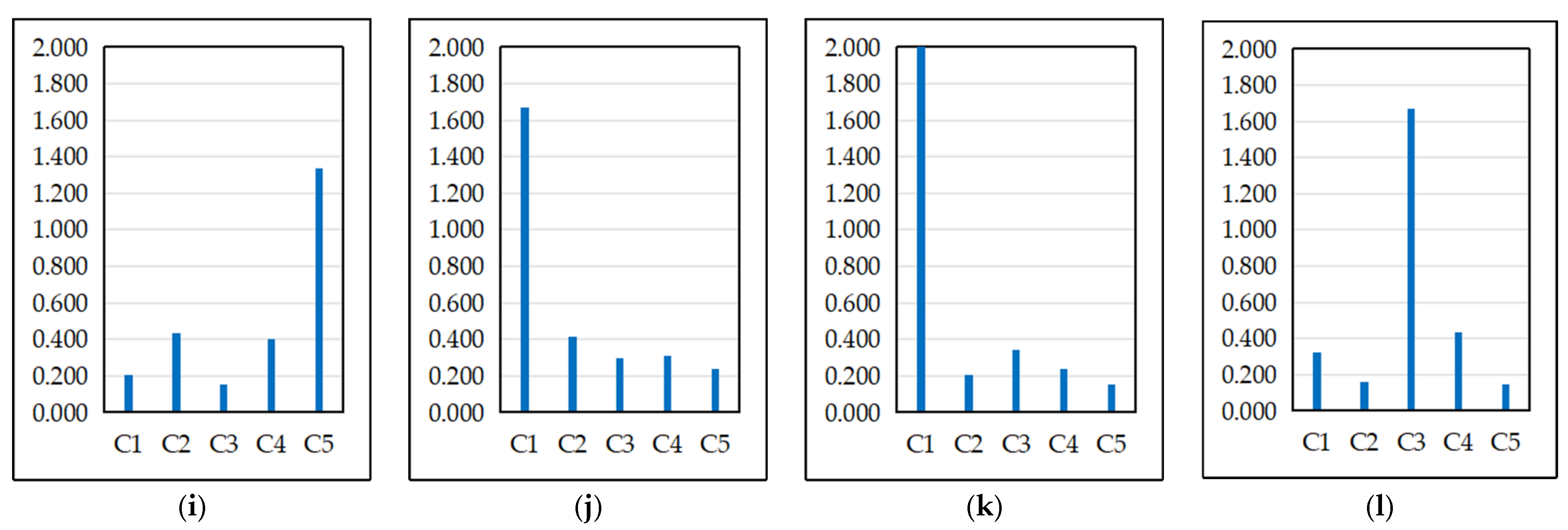

Figure 3 shows the process of constructing the complete binary tree

based on the river channel elements

and the control point sets

.

Figure 3a shows the cluster control point sets

,

Figure 3b shows the selected sample cluster control point set

,

Figure 3c shows the water ecological POI clustering objective function model

, and

Figure 3d shows the generated water ecological POI clustering complete binary tree

based on

. The complete binary tree

is the key model for constructing the clustering algorithm [

25].

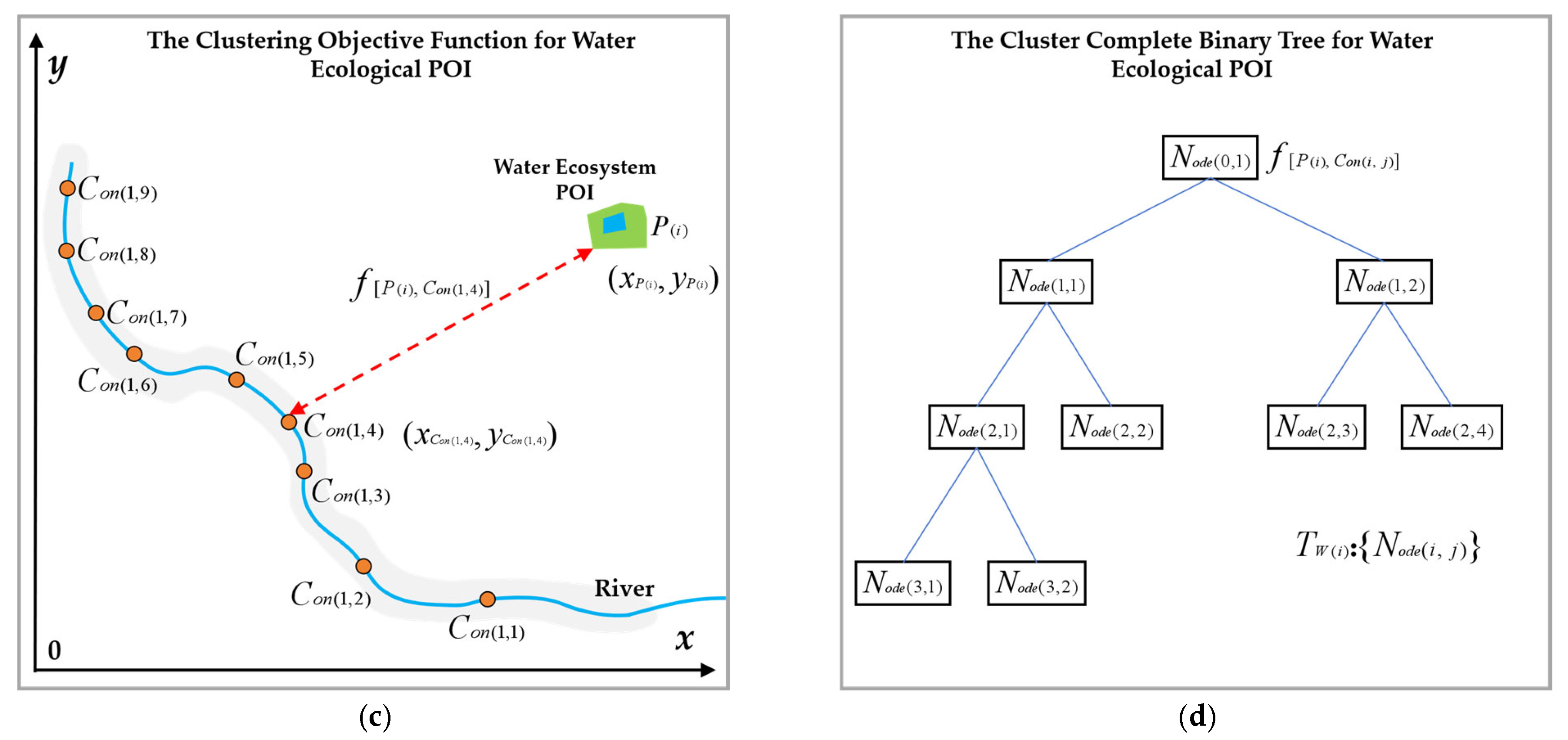

The water ecological POI spatial clustering model based on the improved water network space AGNES algorithm is constructed as follows.

Figure 4 shows the process of constructing the clustering algorithm model [

26]:

Step 1: Collect and model the river water network data.

(1) Construct the coordinate system .

(2) Determine the number of water ecological POI elements to be clustered and their coordinates and .

(3) Based on the urban geospatial data, construct and .

(4) Extract number of river channel elements from the and construct the dataset .

Step 2: Model the control point set and construct the matrix .

(1) Project the and to form the coordinate system .

(2) Take the element in , determine the control points formed by the intersection of and and construct control point set , store them in the corresponding first row of the matrix , and determine the row rank .

(3) Take the element in , determine the control points formed by the intersection of and and construct the control point set , store them in the corresponding second row of the matrix , and determine the row rank .

(4) Repeat the above steps. Take , traverse , determine the control points formed by the intersection of and and construct the control point set , store them in the corresponding No. row of the matrix , and determine the row rank , till the matrix arrives at full rank.

(5) Determine the coordinates and of each control point .

Step 3: Build the spatial relationship model between the water ecological POI element and the element , and extract from the entire POI element set.

(1) Take the first row point set of the matrix , with row rank and row elements , corresponding to the river channel element .

(2) Construct a complete binary tree with number of nodes, denoted as .

(3) Calculate , subscript traverses . Compare and :

① If , store to the parent node and store to the child node .

② If , store to the parent node and store to the child node .

(4) Take , Compare and :

① If :

(i) If , store , and to the parent node , child node and .

(ii) If , store , and to the parent node , child node and .

(iii) If , store , and to the parent node , child node and .

② If :

(i) If , store , and to the parent node , child node and .

(ii) If , store , and to the parent node , child node and .

(iii) If , store , and to the parent node , child node and .

(5) Repeat the above steps, take , ,…, and make a comparison. According to the binary tree storage rules, store the elements to each node of the binary tree .

(6) When the traversal is complete, , the binary tree is stored and forms a large tree. The function value stored in the current parent node is the optimal spatial relationship value between the POI element and river element , denoted as .

(7) Return to Step (1), take the second row point set of the matrix , with row rank and row element , corresponding to the river channel element . Calculate the function values between the POI element and elements . Traverse and store the elements to each node of the binary tree according to the storage rules of the binary tree. The function value stored in the current parent node is the optimal spatial relationship value between the POI element and river channel element , denoted as .

(8) Repeat steps (1) to (6) until all rows of the matrix form a binary tree , resulting in number of binary trees with stored value for each tree’s parent node .

(9) Build a complete binary tree containing number of nodes, traverse all the stored values of the parent nodes of the river element binary trees, and store them in the complete binary tree according to the storage rules of the complete binary tree. Take the element value corresponding to the parent node as the maximum value of all the river element binary trees. Search for the corresponding row of matrix , and the related No. channel element is the cluster corresponding to the POI element .

(10) Store the POI element in the first element position of the cluster row corresponding to the No. channel element in the clustering matrix . The clustering process of the POI element ends.

Step 4: Return to Step 3 and extract from the set of all the POI elements.

(1) According to the Step 3 algorithm, output a complete binary tree of all the river channel elements in the dataset corresponding to , and output number of parent nodes .

(2) Build a binary tree of the river channel elements containing number of nodes, and take the corresponding element of its parent node.

(3) Search for the corresponding row of matrix , and the corresponding No. channel element is the cluster corresponding to the POI element .

(4) Judge the first element position of the cluster row corresponding to the No. river channel element in the clustering matrix . If it is an empty element, store the POI element . If it is a non-empty element, store it in the second element. The clustering process of the POI element ends.

Step 5: Continue searching for other POI elements and then calculate according to the algorithm from Step 3 to Step 4. Search for the corresponding row of matrix . The corresponding No. channel element is the cluster corresponding to the POI element , and the POI element is stored in . Traverse until the No. element is stored in the matrix . Output the clustering matrix .

3.2. Logistics Distribution Center Location Model Based on Water Ecological POI Clustering

The modeling basis of the POI logistics route-planning algorithm is to select the material distribution center as the starting and ending points of the route, and the water ecological POIs that require material distribution as route nodes. The route completes the delivery in a certain order. Under the constraints of the urban geographic space, the key condition for controlling the logistics costs and pollutant emissions is to determine the spatial relationship between the distribution center of assembly materials and the water ecological POIs. That is, when the water ecological POIs to be delivered are determined, the optimal location of the distribution center is achieved by constructing a spatial relationship model between the distribution center and POIs to ensure that the materials depart from the optimal location of the distribution center and minimize the logistics costs and pollutant emissions [

27,

28]. Based on the modeling idea, we established a logistics distribution center location model based on the water ecological POI clustering, the distribution center dataset, and the POI dataset to be delivered. The material assembly points with material reserve capacity in the city are defined as the distribution centers

. Its coordinates are denoted as

and

. The distribution center is the starting and ending point of the POI logistics route. The number of candidate distribution centers is

.

Definition 5.

The closeness between

and cluster

is determined by the closeness algorithm between the control points of

and

. Define the closeness model

as Formula (7). The value rules for parameters

and

are the same as Formulas (4)–(6):

Definition 6.

The spatial relationship between

and POIs to be delivered is defined as the closeness model

, as shown in Formula (8). When the number of POIs to be delivered is

, the average closeness model between

and

number of POIs

is defined as

, as shown in Formula (9). The value rules for parameters

and

are the same as Formulas (4)–(6):

Definition 7.

Construct a

dimension matrix to store the closeness relationship between

and

. The No.

row represents the No.

cluster

, and the column represents the No.

center

with the highest closeness value to

. Formula (9) is the matrix

,

represents

, and

represents that there are

number of

with high closeness values in

:

The relationship between and cluster is determined by the closeness model and could be transformed into a closeness relationship with the control points of the river element to . We construct a complete binary tree containing number of nodes for storing the closeness values . This binary tree is defined as the distribution center closeness complete binary tree, denoted as . Among them, represents the number of control points for rivers , that is, the number of control points for the cluster . The subscript corresponds to the No. distribution center , and the superscript indicates the closeness relationship with the No. cluster . Corresponding to number of clusters , the number of complete binary trees output number of parent nodes, , , and the cluster corresponding to the optimal parent node is the cluster with the highest degree of closeness to the distribution center. Then, calculate the number of between number of the candidate distribution centers and number of the POIs to be delivered. We construct a complete binary tree containing number of nodes to store the values . This binary tree is defined as the distribution center optimal location, a complete binary tree, denoted as .

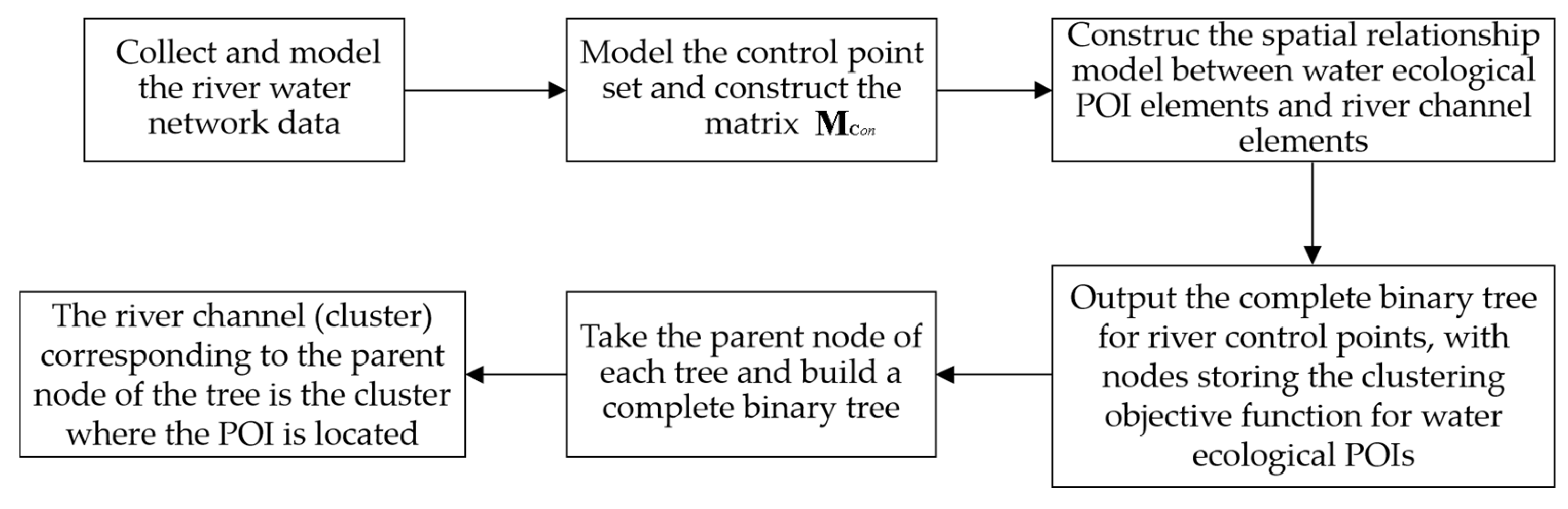

We constructed the logistics distribution center location model based on water ecological POI clustering to determine the optimal starting and ending points of water ecological POI logistics routes.

Figure 5 shows the process of constructing the distribution center location algorithm model:

Step 1: Collect the basic modeling data.

(1) Determine the number of candidate distribution centers and their coordinates and in the urban coordinate system .

(2) Determine the number of POI elements to be delivered and the coordinates and .

(3) Determine the control points and coordinates and of all clusters corresponding to the river channels .

(4) Establish the closeness matrix .

Step 2: Build the closeness relationship between number of candidate distribution centers and number of clusters . Select the distribution center and cluster , and construct the distribution center closeness complete binary tree .

(1) Take the first row of the control points in the cluster matrix , with row rank and row element , corresponding to the river channel element and cluster .

(2) Construct a complete binary tree with a node number count of , denoted as .

(3) Traverse the subscripts from 1 to and calculate .

(4) Compare the current , ,…, . Nodes 1 to Note are stored according to the maximum complete binary tree rule.

(5) Repeat steps (3) to (4) until , the traversal is complete, and the output is .

(6) Take the parent node and the corresponding function value of the binary tree .

Step 3: Return to Step 2, select the distribution center and cluster , and construct the distribution center closeness complete binary tree .

(1) Take the No. row of the control points in the cluster matrix , with row rank and row element , corresponding to the river channel element and cluster .

(2) Construct a complete binary tree with a node number count of , denoted as .

(3) Traverse the subscripts from 1 to and calculate .

(4) Compare the current , ,…, . Nodes 1 to Note are stored according to the maximum complete binary tree rule.

(5) Repeat steps (3) to (4) until , the traversal is complete, and the output is .

(6) Take the parent node and the corresponding function value of the binary tree .

Step 4: Repeat the algorithm from Step 2 to Step 3 and traverse the cluster subscripts .

(1) Output the closeness values between the distribution center and number of clusters.

(2) Select and determine its corresponding cluster , which has the highest degree of closeness with the distribution center .

(3) Store in the No. row corresponding to the cluster in the closeness matrix .

Step 5: Return to Step 2 and calculate according to the algorithm from Step 2 to Step 4.

(1) Traverse and calculate the closeness relationship between distribution center and cluster .

(2) Select and determine its corresponding cluster , which has the highest degree of closeness with the distribution center .

(3) Store in the No. row corresponding to the cluster in the closeness matrix .

(4) For the distribution center , after traversal , output a full ranked matrix . The No. row of the matrix corresponds to the distribution centers with the highest closeness values for the cluster.

Step 6: Search for number of water ecological POI elements to be delivered. Initialize the counter , in which represents the number of occurrences for the cluster .

(1) Search for element , determine , and iterate for the counter of cluster .

(2) Search for element , determine , and iterate for the counter of cluster .

(3) Repeat the above search. Search for the element , determine , and iterate for the counter of cluster .

(4) Traverse until all the water ecological POI elements have been searched.

(5) Count for each cluster and select the corresponding cluster of as the optimal location cluster, denoted as .

Step 7: Locate the row in the matrix for , in which all the distribution centers are the candidate elements for the optimal distribution center, with a quantity of . Construct a complete binary tree for the optimal location of distribution centers with number of candidate distribution centers as nodes.

(1) Note number of candidate distribution centers as , , .

(2) Determine the coordinates and of each distribution center , and identify the number of water ecological POI elements to be delivered and their coordinates and .

(3) Construct a complete binary tree with a node number count of , denoted as .

(4) For , traverse subscripts from 1 to , and calculate .

(5) For , traverse subscripts from 1 to , and calculate .

(6) Repeat steps (4) to (5), traverse , for , traverse subscripts from 1 to , and calculate .

(7) Compare the current , ,…, . Store the number of values in number of nodes according to the maximum complete binary tree rule, and output .

(8) Take the parent node and corresponding function value of the binary tree , and the corresponding distribution center is the optimal distribution center for the number of water ecological POI elements to be delivered, which is the starting and ending point of the logistics route.

3.3. Water Ecological POI Logistics Route-Planning Algorithm Based on Symmetrical Simulated Huffman Spatial Searching Tree Algorithm

After determining the optimal distribution center as the starting and ending points of the logistics route, the delivery vehicle departs from the starting point and delivers to the

number of POI elements

in a certain logical order, and finally returns to the starting point. In the coordinate system

, the starting and ending points of the distribution center

and the POI elements

to be delivered are both constrained by the geospatial conditions of the city. When constructing a logistics route with starting and ending points, while the material distribution points are nodes, the cost of the route generated by vehicles comes from two dimensions. One is that the vehicles move between nodes, and different moving routes will generate different costs due to the influence of road distance and road nodes; another factor is that the vehicle starts from the starting point, completes the material distribution of POIs, and finally returns to the destination. This process goes through

number of nodes, and different delivery orders will generate different costs [

29,

30].

Both of the two dimensions have symmetrical features. Firstly, within the logistics sub-interval composed of the distribution points, regardless of whether the logistics vehicle moves from the starting point to the endpoint or from the endpoint to the starting point, under the condition of the same round-trip path and passing through the same road nodes, the moving vector of the logistics vehicle is spatially symmetrical, and the moving distance by the vector iteration is also equally symmetrical. Secondly, within the logistics interval composed of the distribution center and all the distribution points, when the optimal paths for all sub-intervals are determined, the logistics vehicle departs from the distribution center, and under the condition of the same round-trip path and passing through the same distribution point sequence, the moving vector of the logistics vehicle is spatially symmetrical, and the moving distance by the vector iteration is also equally symmetrical. This characteristic ensures the logical rationality of the undirected complete graph when constructing the logistics route model, ensuring that the logistics vehicle maintains symmetry in the moving distances on the round-trip vectors of the same distribution points and delivery order under the same sub-interval path conditions.

Based on the two cost constraints and the symmetrical features, we first construct the optimal route model between the arbitrary two nodes, and then construct the global optimal route model connecting all nodes, outputting the logistics route with the lowest cost and pollutant emissions.

3.3.1. Sub-Interval Optimal Route-Searching Algorithm Based on Symmetrical Simulated Huffman Spatial Searching Tree

According to the modeling idea, we first establish the optimal route between the logistics nodes and search for the route with the lowest cost. The starting and ending points of logistics and the POI elements to be delivered are defined as the logistics route nodes . The logistics route consisting of the distribution center and number of POI elements contains number of nodes, in which the starting and ending points of the route are both , and the middle node of the route is . For nodes , there are , .

In a logistics route, the interval formed by the movement of vehicles between any two adjacent nodes and is the sub-interval of the logistics route, in which is the sub-interval number. The road nodes that vehicles may pass through within a sub-interval are the sub-interval control points , and the number of control points within any sub-interval is specified as . If the starting and ending points remain unchanged, the number of nodes will form number of the sub-intervals, then . The starting point , ending point , and number of the control points of a sub-interval together form a directed weighted edge graph of the sub-interval. Among them , is a directed weighted edge composed of the adjacent vertices , , or . The movement distance between two adjacent points is the edge weight , and represents the two adjacent points , or , and the subscript represents the current found No. weight edge during the iterative searching. According to the directionality of the logistics vehicle movement, each edge in the graph is a directed edge.

Definition 8.

In a directed weighted edge graph

, logistics vehicles may pass through different weighted edges

during their movement from

to

. The distance cost is calculated by iterating through each weighted edge, and the terminal point

is searched for when the last iteration is completed. The distance cost function generated after iterating the No.

weight edge is defined as the dynamic cost function of the logistics sub-interval, denoted as

, as in Formula (11), and

is the dimensionality reduction parameter. The definition of value

is as follows:

(1) If the sum

of distance

meets

,

;

(2) If the sum

of distance

meets

,

;

(3) If the sum

of distance

meets

,

; and so forth.

The first objective of controlling the logistics route costs is to construct an optimal cost model for the sub-intervals

, that is, to construct a searching model that optimizes the function

. The Huffman tree is a type of structural tree with the shortest weighted path. Based on the generation rules of the Huffman tree, we combine the graph of the Huffman tree searching for the optimal path and the directed weighted edge graph

of the sub-intervals to construct a sub-interval optimal route-searching algorithm based on the symmetrical simulated Huffman spatial searching tree [

31,

32]. We search for the optimal path of the sub-intervals

and find the optimal function value

opt:

.

The spatial optimization logic, mathematical foundation, innovation, and correlation with Huffman data encoding of the proposed simulated Huffman spatial searching tree (SHSST) are as follows:

(1) Spatial optimization logic: We simulate the spatial structure of the Huffman tree to search for the path with the minimum cost and redesign the algorithm logic. We use the road nodes of the sub-interval as nodes of the tree and combine them with the movement direction of logistics vehicles in the urban geographic space in the real environment. Then, we determine the feasible paths according to the vehicle movement direction. The road nodes are connected to form the weighted edges along the path searching direction to construct a directed weighted edge graph of the sub-interval. Iteratively, we compare the path costs by searching for globally feasible paths and output the optimal path with the minimum cost.

(2) Mathematical foundation: Search for feasible paths along the direction of logistics vehicle movement, without turning back, and iterate the path cost while searching until the endpoint is reached. Output one feasible path and cost . Continue searching for number of feasible paths and costs in the same way, , . Establish a global route-searching algorithm to search and determine the corresponding route as the optimal path.

(3) Innovation. The constructed SHSST is an innovative algorithm with a structure similar to that of a Huffman tree but with a different algorithmic logic. The innovation is manifested as follows. Firstly, the algorithm logic of the Huffman tree is to search for a tree structure with the minimum weighted path length (WPL), and when calculating WPL, all nodes of the entire tree need to be iterated. The search target of SHSST is not the entire tree, but a single feasible path, involving a subset of the tree node set. Secondly, the Huffman tree is formed by gradually merging the binary trees with the smallest weights to form the tree with the smallest WPL. Each merger selects the two trees with the smallest weights from the current forest. SHSST searches for feasible paths based on the direction of vehicle movement and then searches for the global optimal route with the lowest cost after finding all feasible paths.

(4) Correlation with Huffman data encoding. The traditional Huffman tree can be used for data encoding, while the application goal of SHSST is not data encoding, but to search for the optimal route. The SHSST is not based on the encoding rules of traditional Huffman trees, but an innovative algorithm designed on the basis of the spatial structure of the Huffman tree.

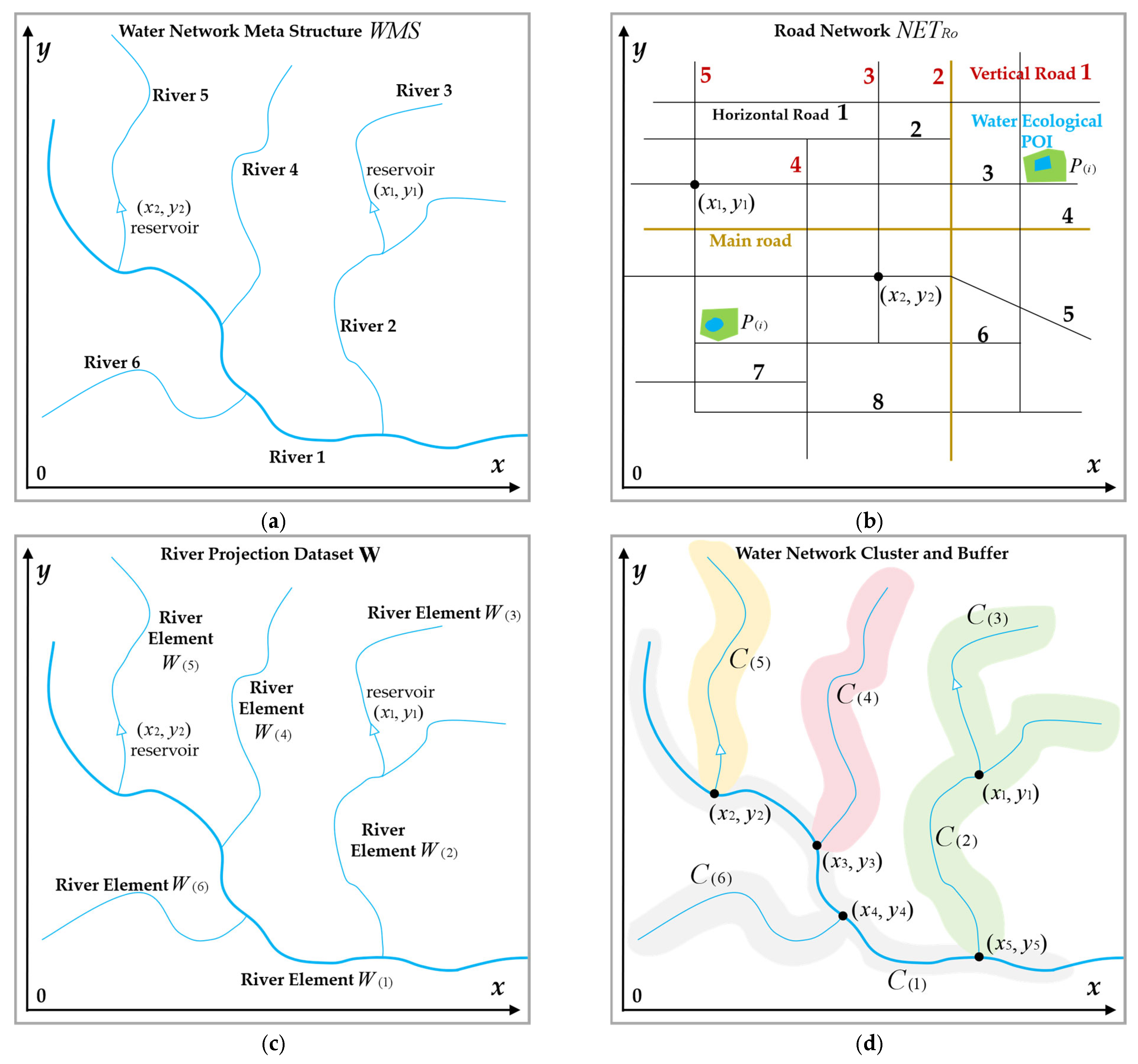

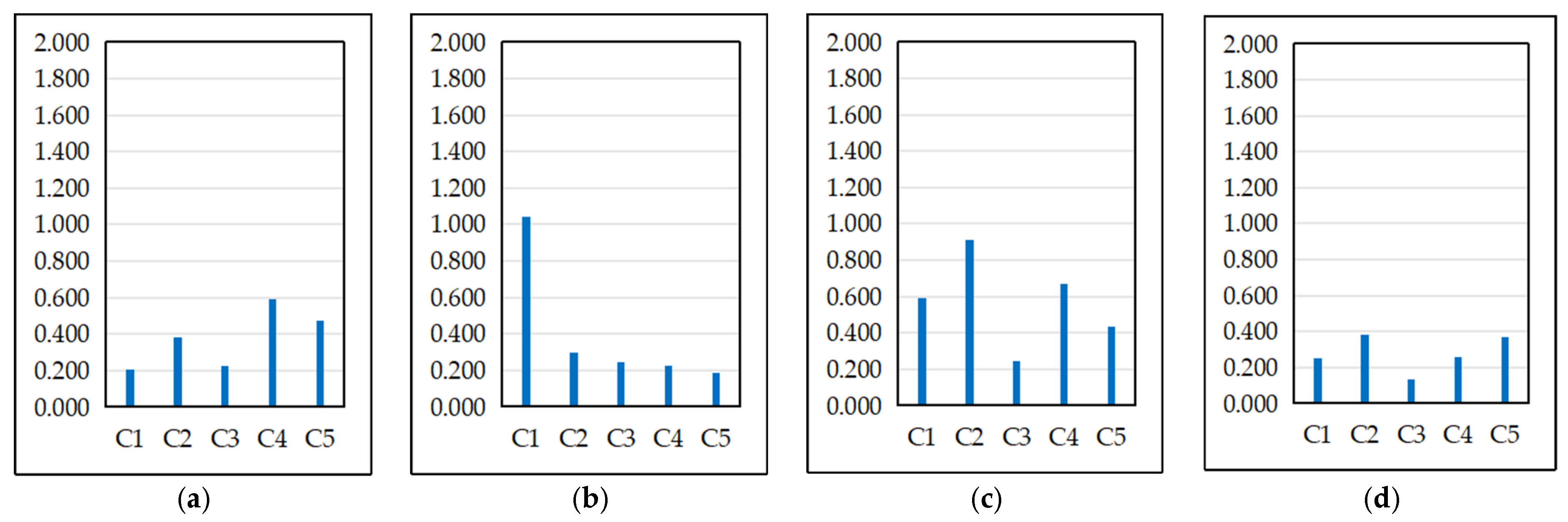

Figure 6 shows the process of constructing the sub-interval coordinate system

, sub-intervals

, and the directed weighted edge graph

between the urban water ecological POIs by the

.

Figure 6a shows the road network, road nodes, and the constructed

within the buffer zone of POIs;

Figure 6b shows the constructed coordinate system

for

based on

Figure 6a;

Figure 6c shows the process of selecting the key control points

from the coordinate system

, determining

and

to form the sub-interval

;

Figure 6d shows the directed weighted edge graph

and sub-interval

.

According to the directional features of the logistics routes, the process of the vehicles moving from the starting point of the water ecological POI to the endpoint of the water ecological POI has the feature of one-way non-turning. Therefore, the process of constructing the simulated Huffman spatial searching tree (SHSST) takes the direction of the vehicle movement as the node searching direction, and the route does not turn back. We stipulate the following:

(1) The parent node of SHSST is the starting point , the highest level node is the endpoint , and the tree node is the key control point .

(2) The tree node storage structure is < , >, in which is the edge weight between the current node and the previous node , and is the total weight of the current searched path when SHSST searches to the node .

(3) At the end of the search for SHSST, it contains multiple feasible paths. The minimum value of the highest-level node is searched, and the path that connects the minimum value is the shortest path in the sub-interval .

Suppose that the List

represents the set of points in the control point set

that have been searched and have a determined distance to the starting point

, and the List

represents the set of points in the control point set

that have not been determined to have a distance to the starting point

, then there is

,

. The cost

of the current searching state from the starting point

to the control points

in the set

is defined as the cost of the shortest path that starts from the starting point

and passes through the control points in the List

, but directly arrives

without passing through the control points in the List

. For all control points

in the set

, if there is a weight edge of a connected path from the starting point

to the current searching point

, then there is

, otherwise,

is specified. For the set

of all control points

, search for the point that makes the

minimum:

In Formula (12),

is the minimum cost obtained by the searching from the starting point

to

, and

is currently the closest point in the set

to

. Remove

from

and store it in the List

. For all other points

in the set

that are adjacent to the current one

, iteratively update

according to Formula (13) until they satisfy

and

.

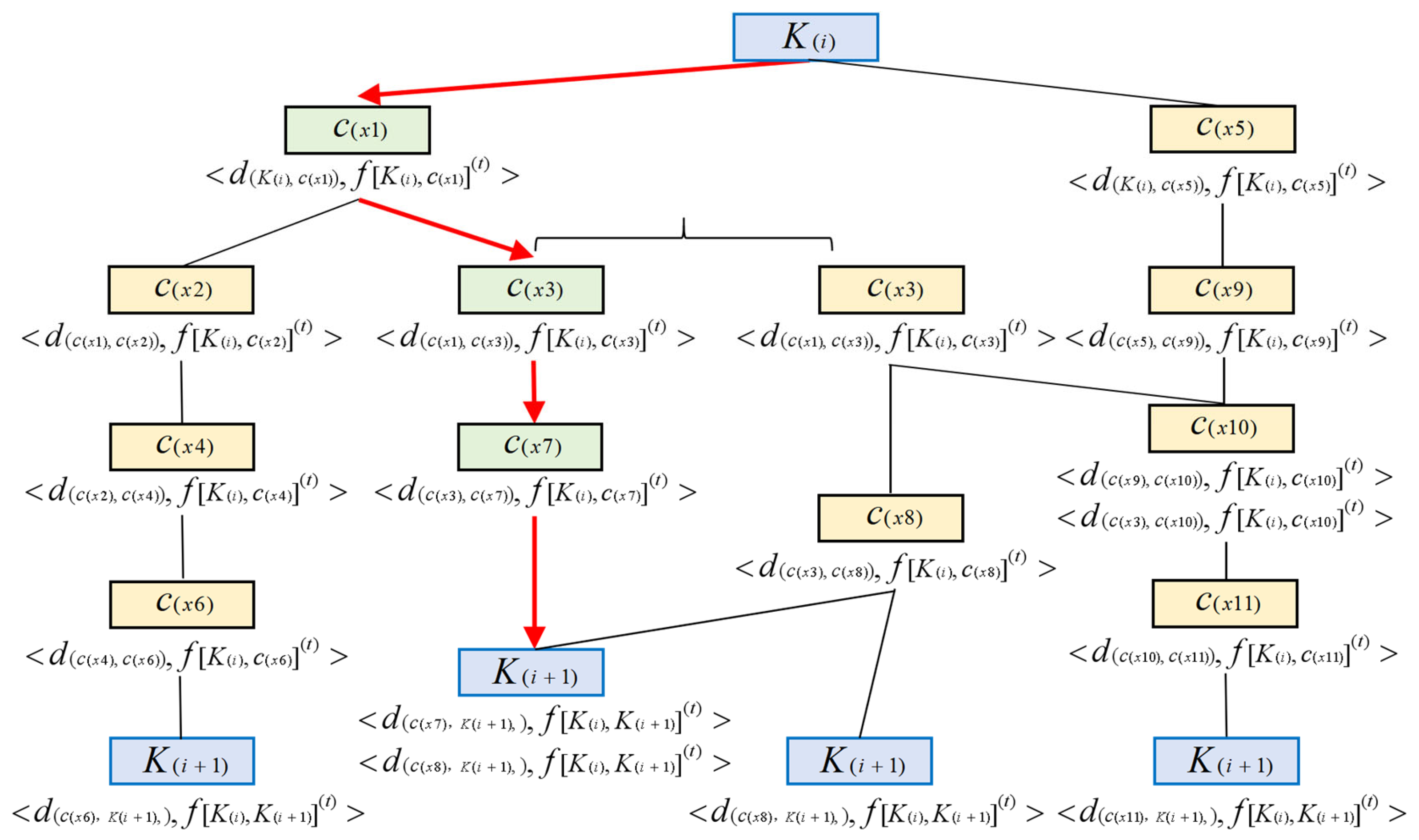

According to the SHSST modeling principle, we construct the sub-interval optimal route-searching algorithm based on the symmetrical simulated Huffman spatial searching tree as follows:

Step 1: In the graph , set as the previous point in the shortest path from the starting point to the point , and is the set containing points , , and in the SHSST. Initialize , .

Step 2: For any , if there is , then there must be the following: , ; Otherwise, , .

Step 3: Search , so that , then the is the minimum cost from to .

Step 4: Update , .

Step 5: If , the algorithm ends; Otherwise, turn to Step 6.

Step 6: For all the adjacent points

to

, if they satisfy

, in which

satisfies the Formula (14),

is the dimensionality reduction parameter, the

is the cost from

to

, the

is the cost from

to

adding the cost from

to

, then turn to Step 3; Otherwise, for the points

that are not satisfied, set

,

, and turn to Step 3.

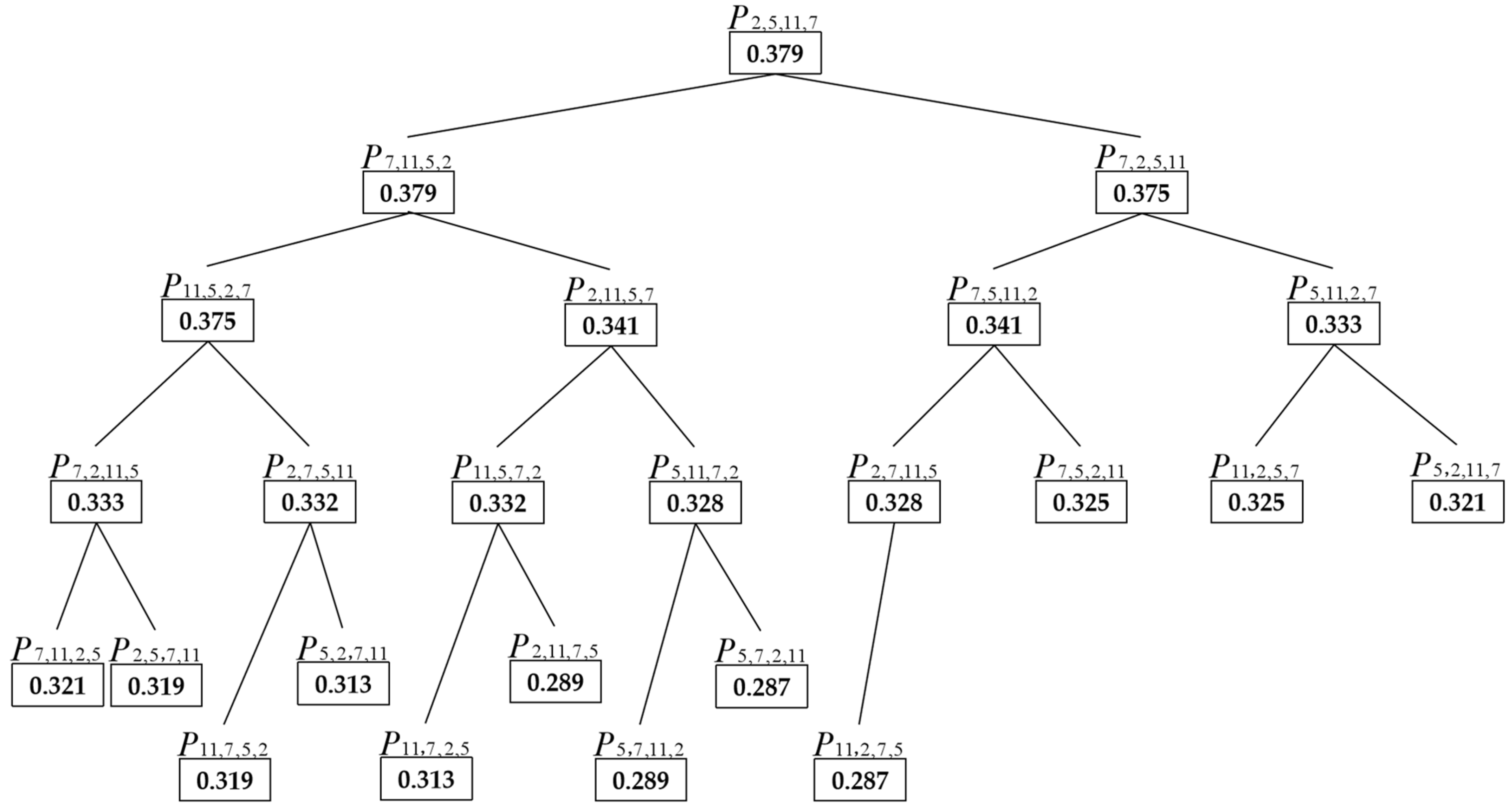

According to the algorithm modeling process, construct the symmetrical simulated Huffman spatial searching tree model, SHSST, as shown in

Figure 7, in which each node represents a sub-interval control point

and the connecting edges of the tree are logistics paths. The red path in the

Figure 7 is an example of the optimal path in the sub-interval.

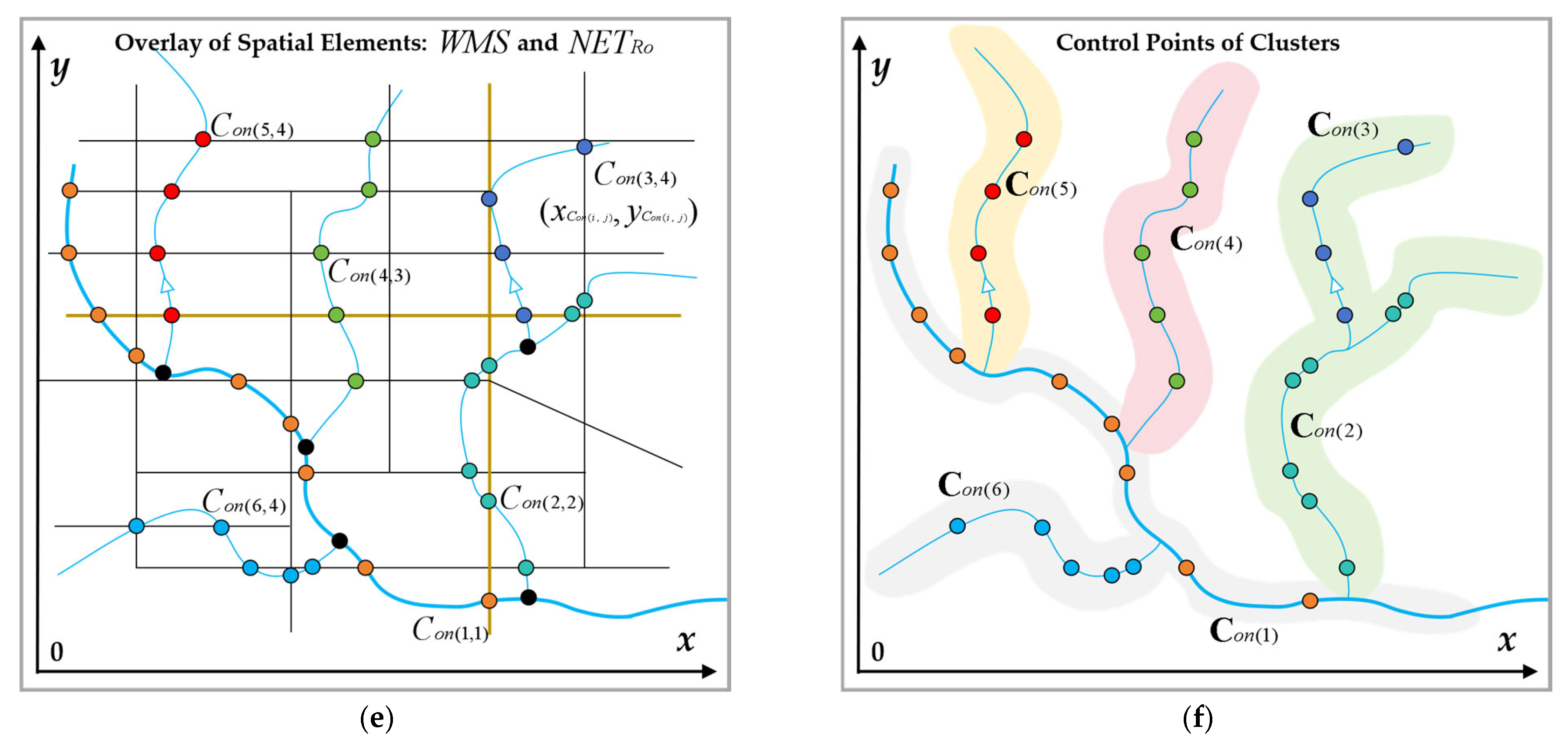

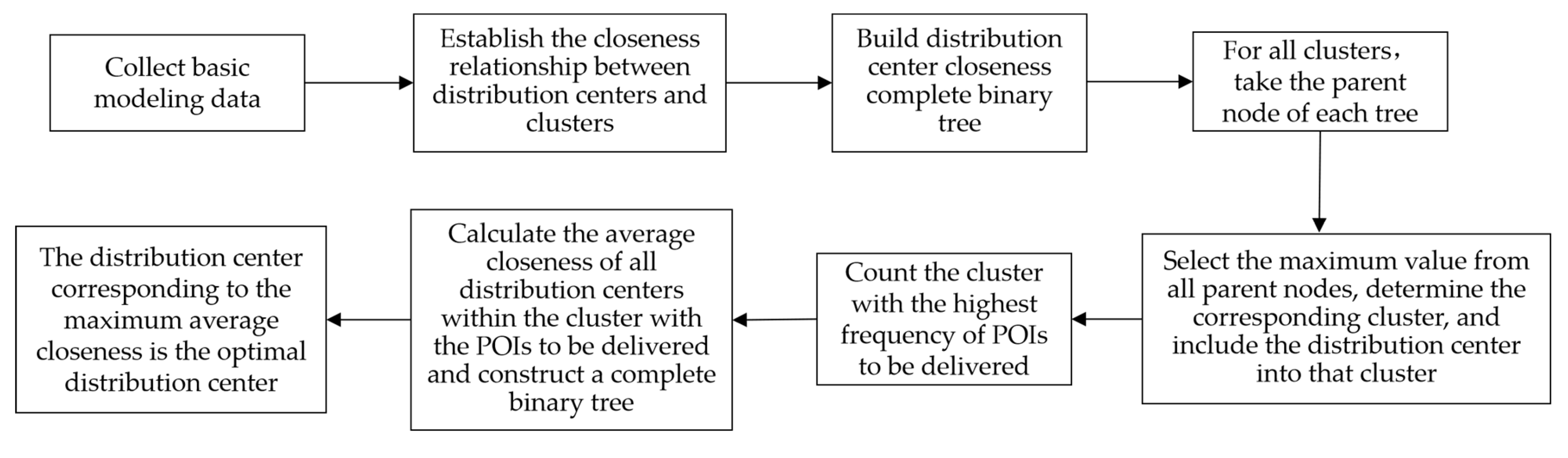

3.3.2. Global Logistics Route-Planning Algorithm Based on Undirected Complete Graph Spatial Search

On the basis of constructing the sub-interval SHSST model, we determine the logistics path

with the minimum cost

for each sub-interval. The logistics vehicle starts from the departure point

, completes the material distribution of

number of water ecological POIs, and finally returns to the destination

, forming a closed logistics route. The closed route contains

number of sub-intervals

. In non-emergency situations, due to the disorderliness of the logistics distribution, the logistics vehicles show the feature of disorderliness in the material distribution to the

number of water ecological POIs. That is, when the distribution order changes, the logistics route and cost also change accordingly [

33,

34]. Based on this characteristic, we construct the global logistics route-planning algorithm based on the undirected complete graph spatial search.

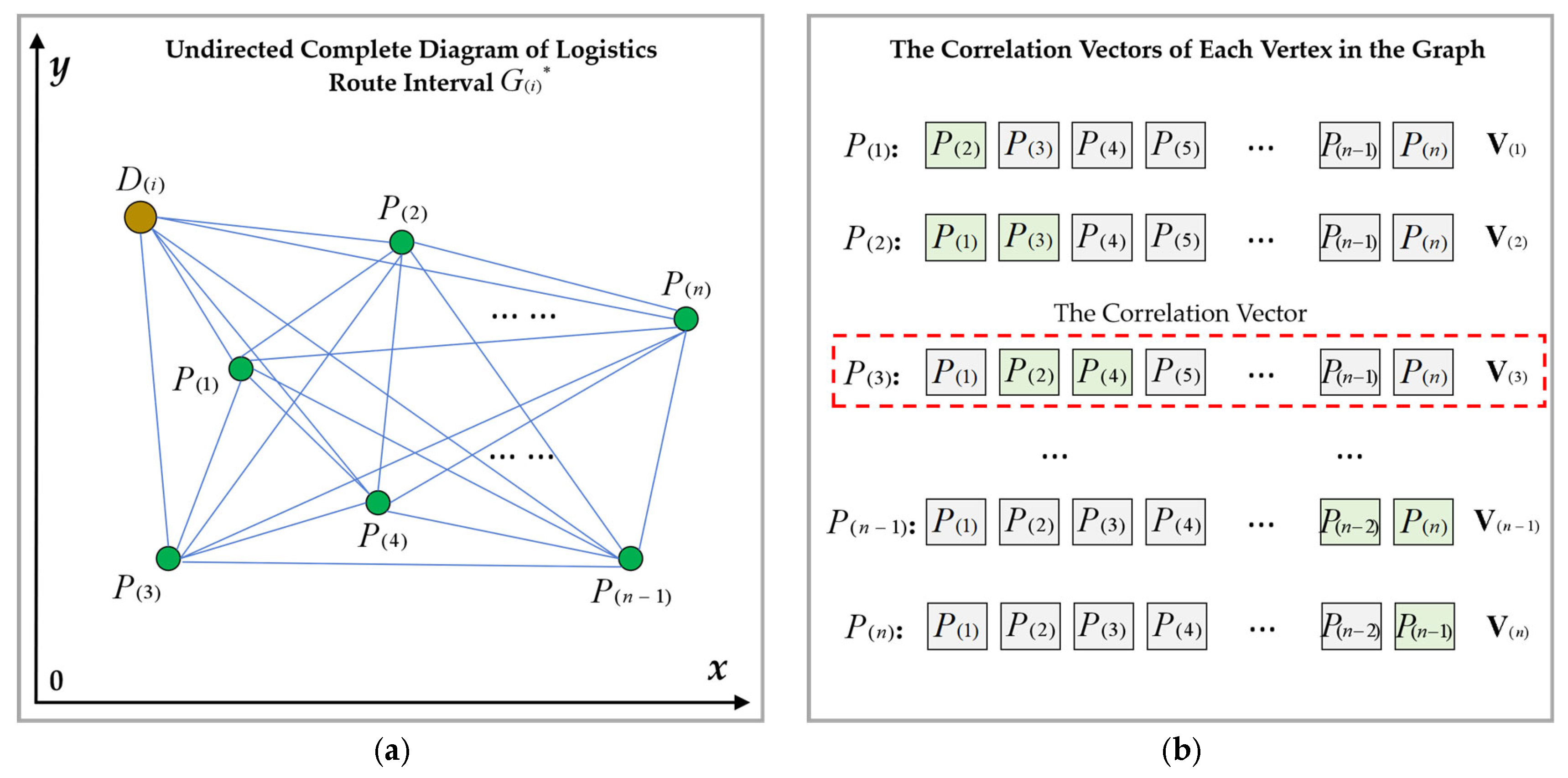

Specifically, the logistics vehicle starts from the departure point , passes through number of water ecological POI nodes for material distribution, and finally returns to the destination . The complete route formed by this process is the logistics route interval , in which represents the No. type of interval. Construct a dimension logistics route interval vector for storing logistics route nodes , in which represents the No. type of vector. The vector contains number of elements, with No. element specified as . The elements and store , and ~ store POIs .

According to the disorderliness of the logistics distribution, the logistics route intervals have the undirected features, including

number of nodes and

number of sub-intervals

. Construct a graph containing

number of vertices and

number of undirected edges, with each vertex connected to the other

number of vertices, which forms an undirected complete graph, denoted as

. Discretize the graph

. For any vertex

of

, a

dimension vector

is constructed by connecting the remaining

number of vertices through the undirected weighted edges. Its elements store the remaining

number of vertices, and the vector is the discrete correlation vector of the graph

. Set the vector element as

,

,

.

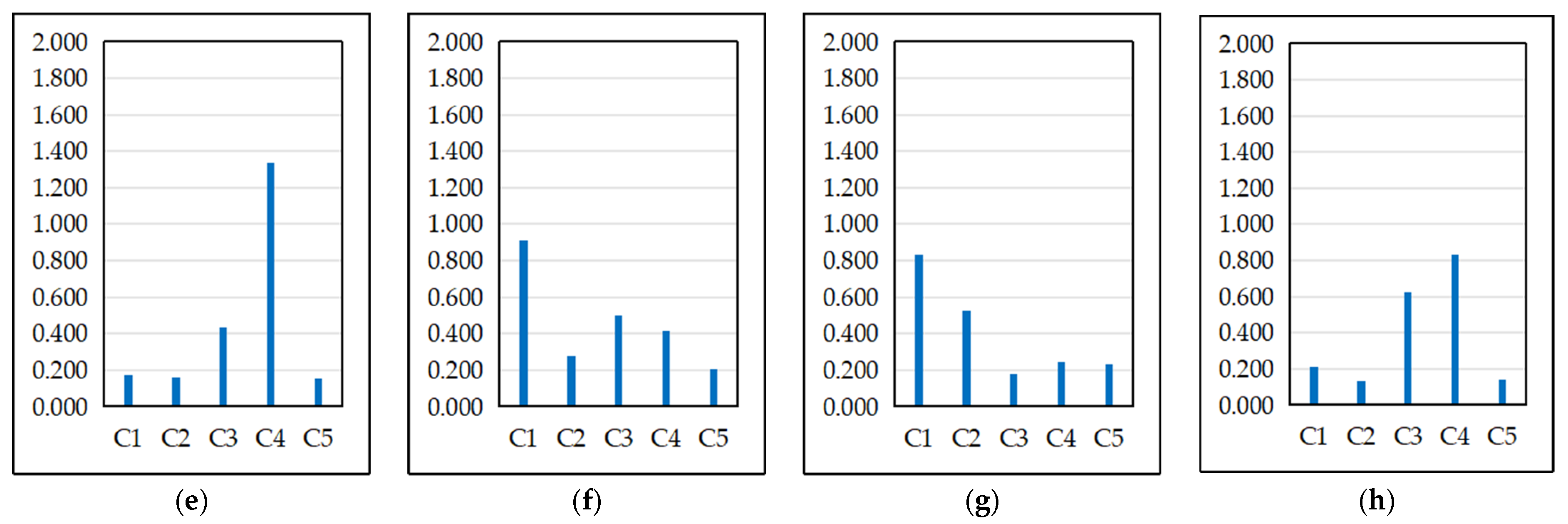

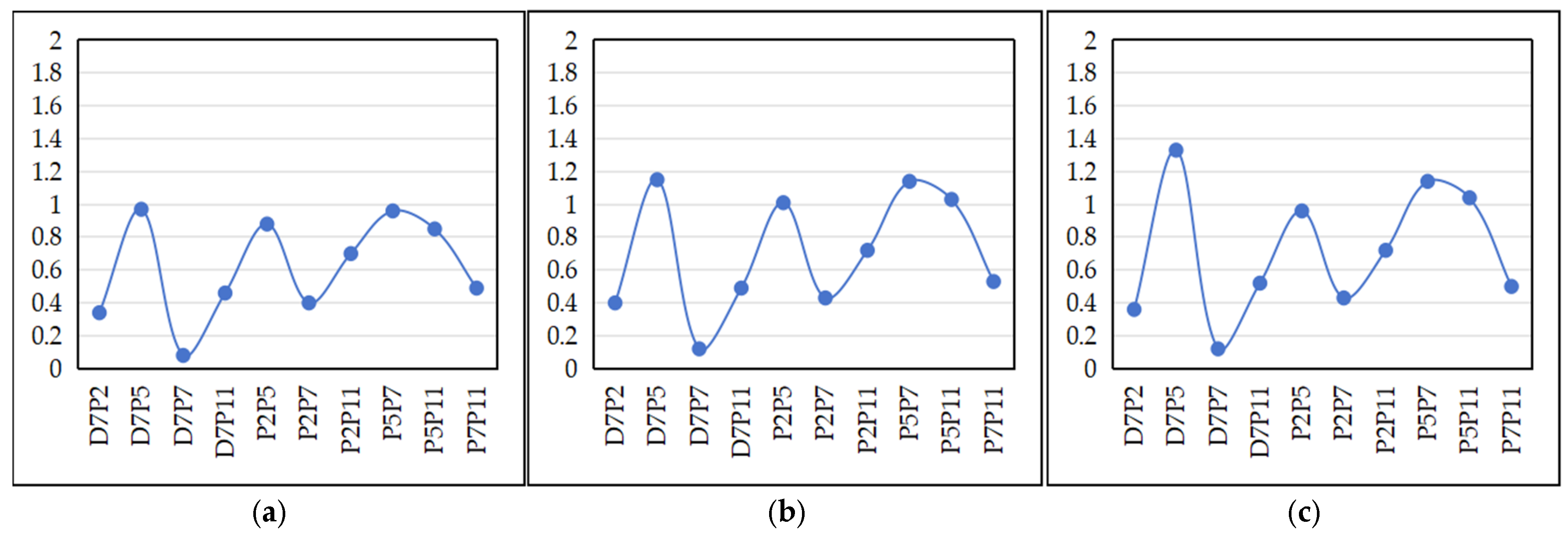

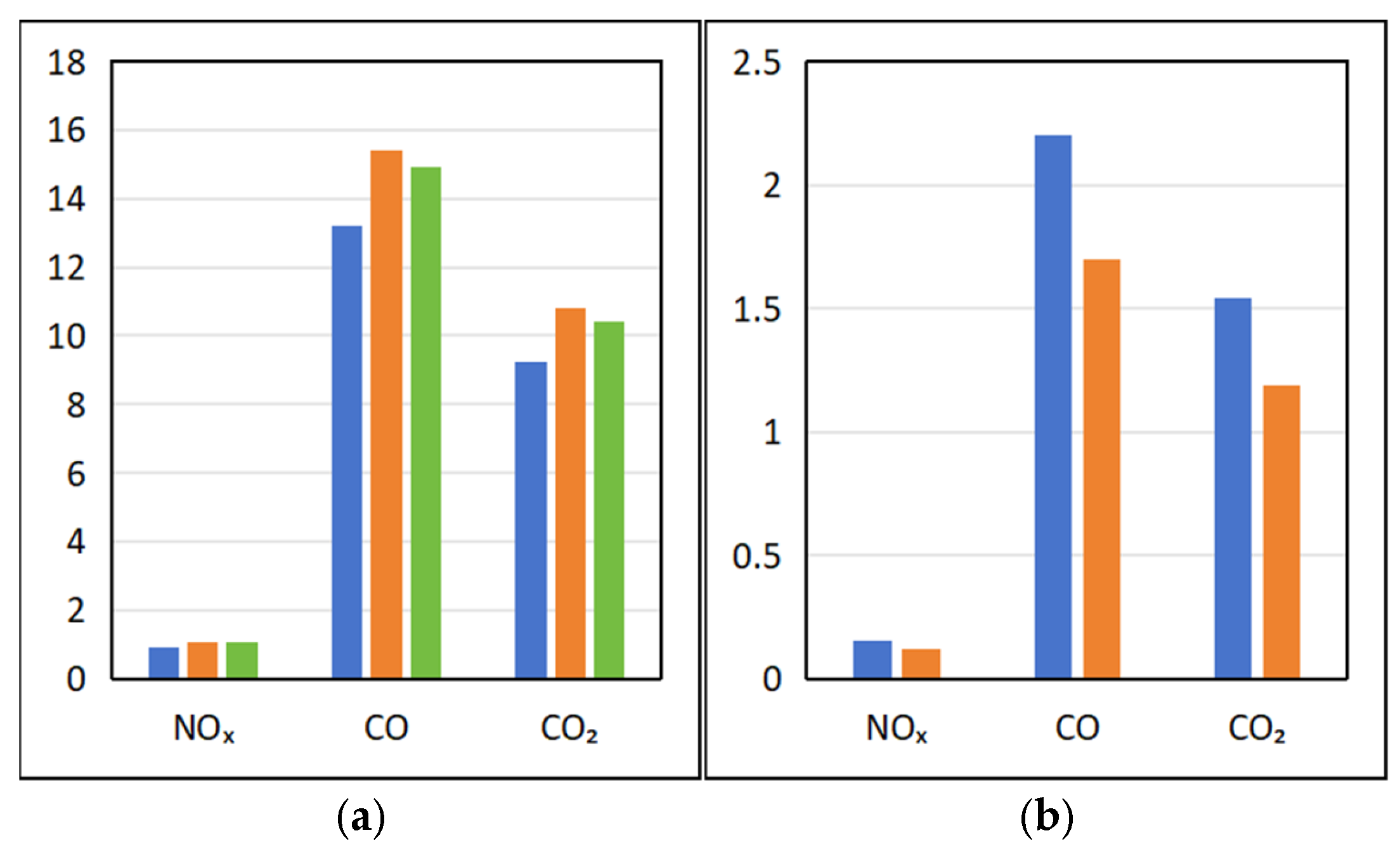

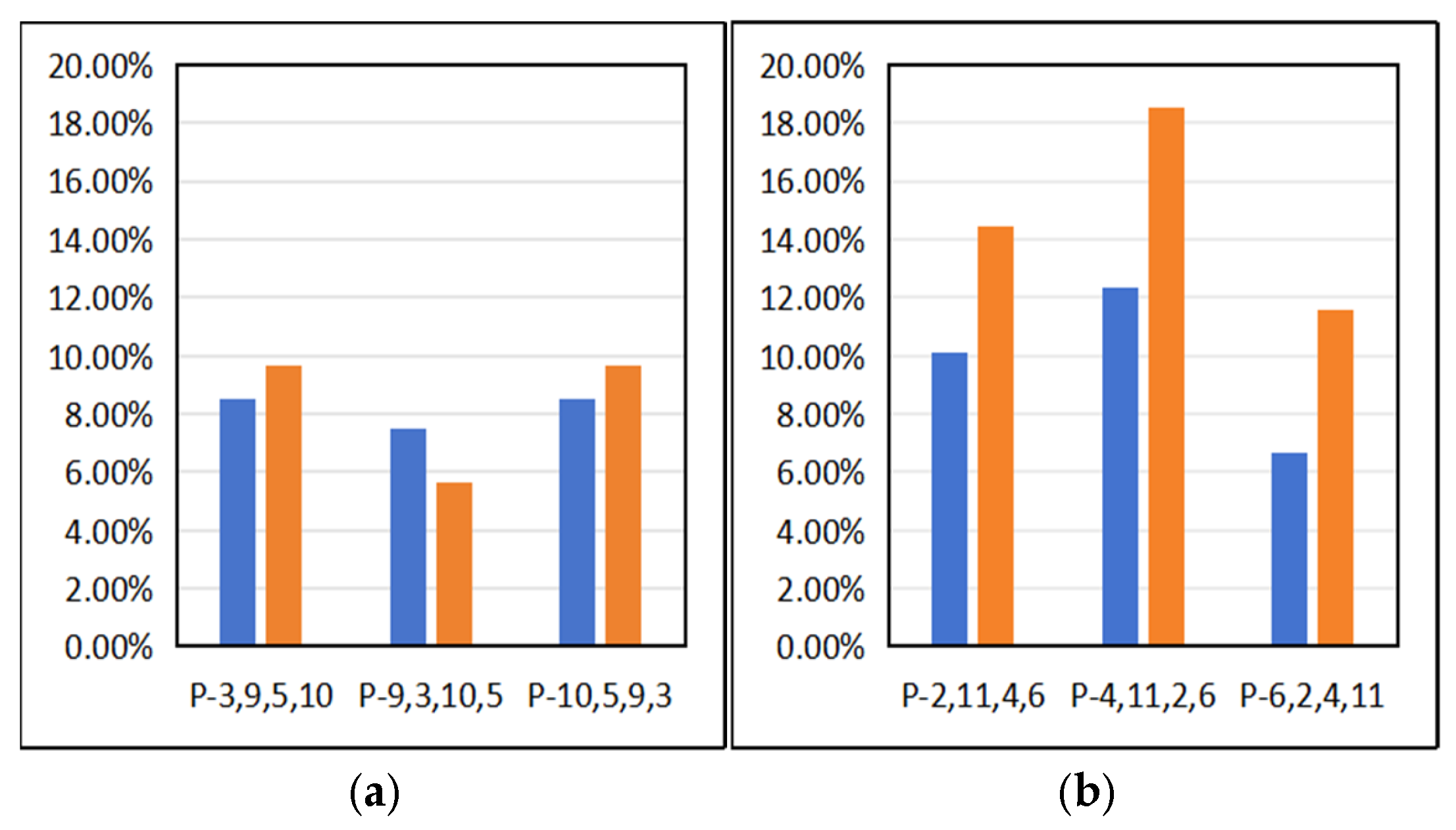

Figure 8a shows the undirected complete graph

, and

Figure 8b is the example of the correlation vectors of each vertex obtained after the discretization of graph

.

Based on the vector

and the sub-interval cost

, the logistics interval cost function

is constructed as Formula (15), in which the

represents the No.

kind of vector. It represents the different generated route directions when the logistics sequence changes. Based on the

number of logistics distribution POI nodes

and possible types of routes, it meets

,

.

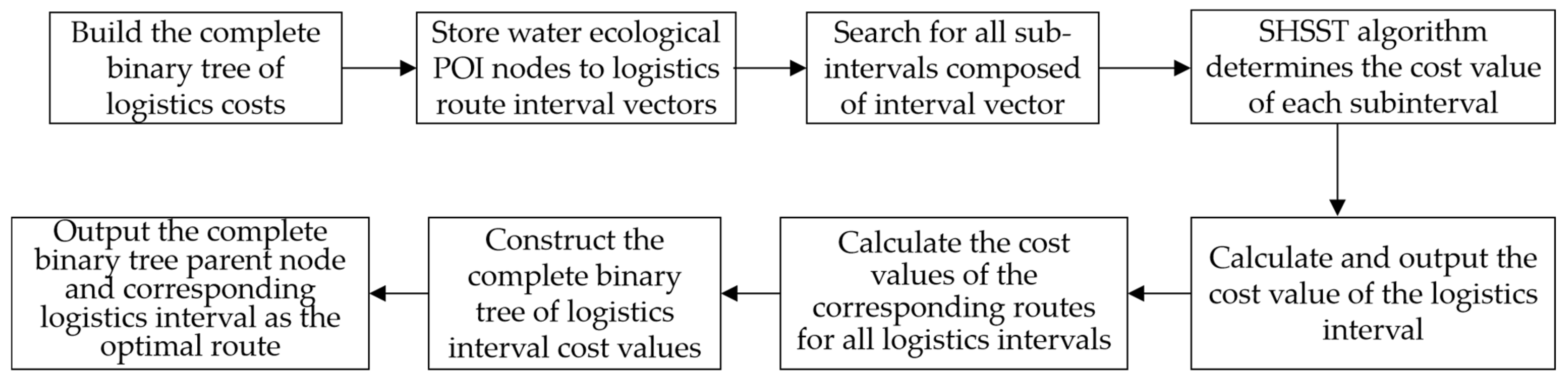

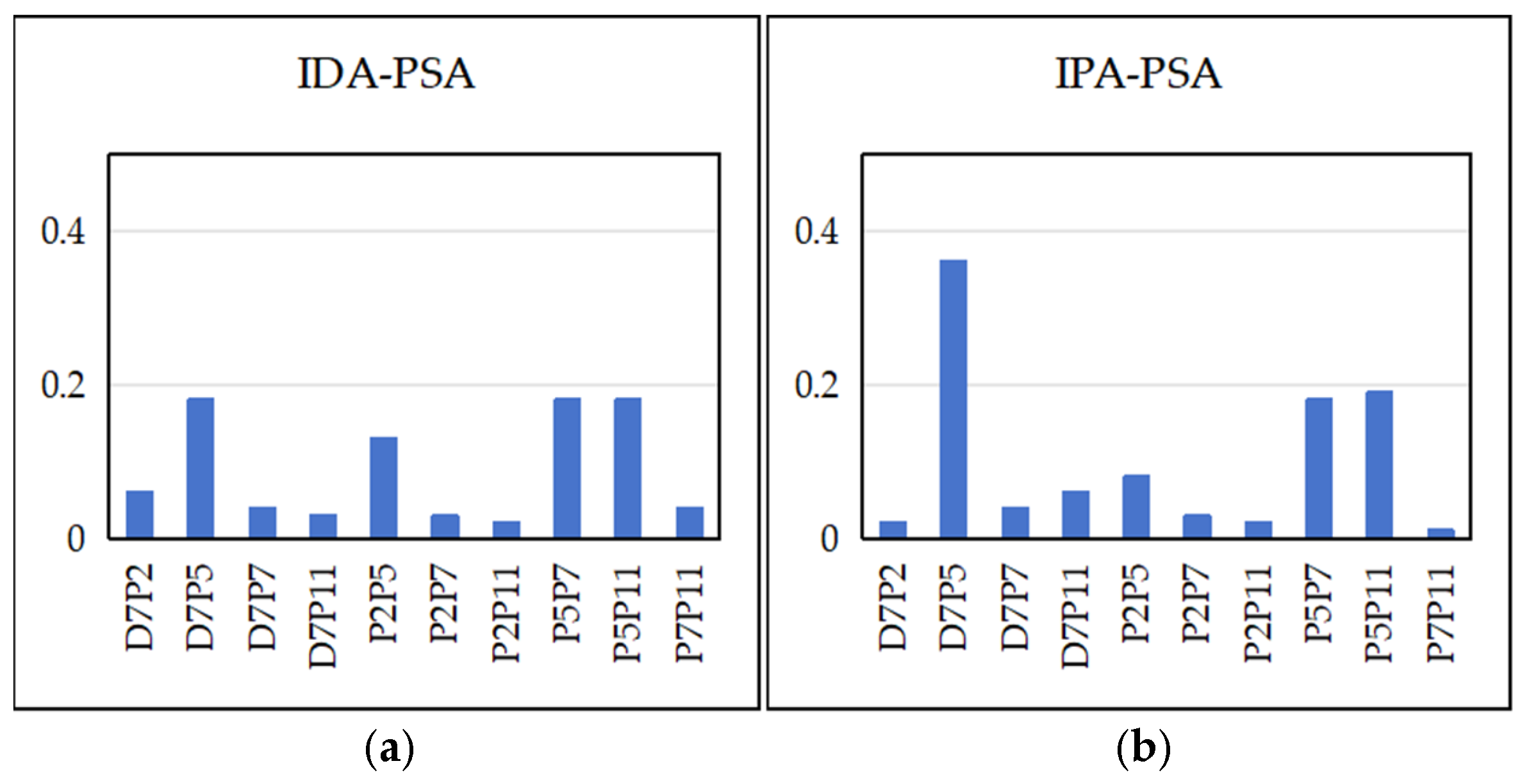

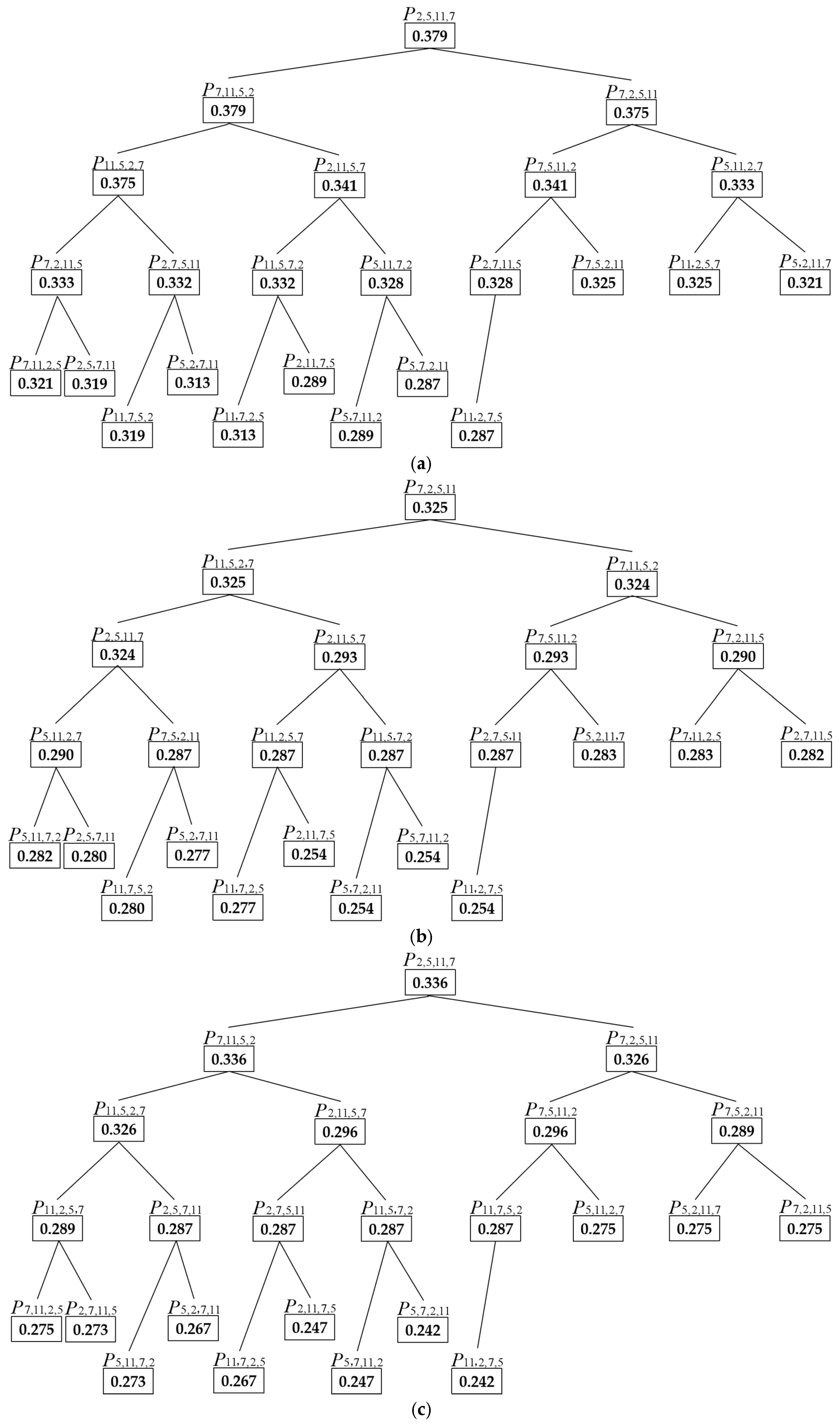

Based on the number of the logistics intervals output by the iteration, we calculate number of the cost functions for the logistics intervals, then construct the logistics cost complete binary tree with number of nodes to store .

We construct the global logistics route-planning algorithm based on the undirected complete graph spatial search.

Figure 9 shows the flowchart of the constructed algorithm.

Step 1: Build a logistics cost complete binary tree containing number of nodes. Set , initialize , and establish the first vector . Store the selected starting and ending points in the element and .

Step 2: Store number of water ecological POI nodes to elements ~.

(1) Initialize number of correlation vectors : ~ for .

(2) In , randomly select the arbitrary element ~ and store it as an element in the vector .

(3) In , randomly select the arbitrary element ~ and determine the following:

① If , store ~ into the element of the vector .

② If , delete , return to Step (3) to select and judge until the selected meets condition ①, and then store it in the element .

(4) According to the method in Step (3), randomly select an arbitrary element ~ from , , and determine the following:

① If , then among them the traverses . Store ~ into the element of the vector .

② If , delete , return to Step (4) to select and judge until the selected meets condition ①, and then store it in the element .

(5) Repeat Step (4) until the vector search is complete. Store the elements that meet the conditions into . The vector storage is completed.

Step 3: Based on the vector and the element storage structure, search for number of sub-intervals consisting of number of nodes . Determine the cost value of each sub-interval and calculate to output the interval cost value .

Step 4: Return to the Step 1, set , initialize , and set up the second vector .

(1) Store number of water ecological POI nodes to elements ~.

(2) Based on the vector and the element storage structure, search for number of sub-intervals consisting of number of nodes .

(3) Determine the cost value of each sub-interval and calculate to output the interval cost value .

Step 5: According to the algorithm from the Step 3 to Step 4, for any , initialize the and establish the No. vector , and calculate to output interval cost . Traverse and output number of cost values of the logistics intervals .

Step 6: Store number of cost values to the complete binary tree .

(1) Take and and compare the following:

① If , store to the parent node and store to the child node .

② If , store to the parent node and store to the child node .

(2) Take , and further compare the following:

① If :

(i) If , store , , and to the parent node , child node , and .

(ii) If , store , , and to the parent node , child node , and .

(iii) If , store , , and to the parent node , child node , and .

② If :

(i) If , store , , and to the parent node , child node , and .

(ii) If , store , , and to the parent node , child node , and .

(iii) If , store , , and to the parent node , child node , and .

(4) Repeat the above steps, take , ,…, and make the comparison. According to the binary tree storage rules, store the elements to each node of the binary tree.

(5) For , when the traversal is complete, the binary tree completes the storage and forms the largest tree.

Step 7: For the output complete binary tree , select the parent node whose stored corresponding to vector is the optimal logistics route with the lowest cost and pollutant emissions.