Theoretical Analysis of Blood Rheology as a Non-Integer Order Nanofluid Flow with Shape-Dependent Nanoparticles and Thermal Effects

Abstract

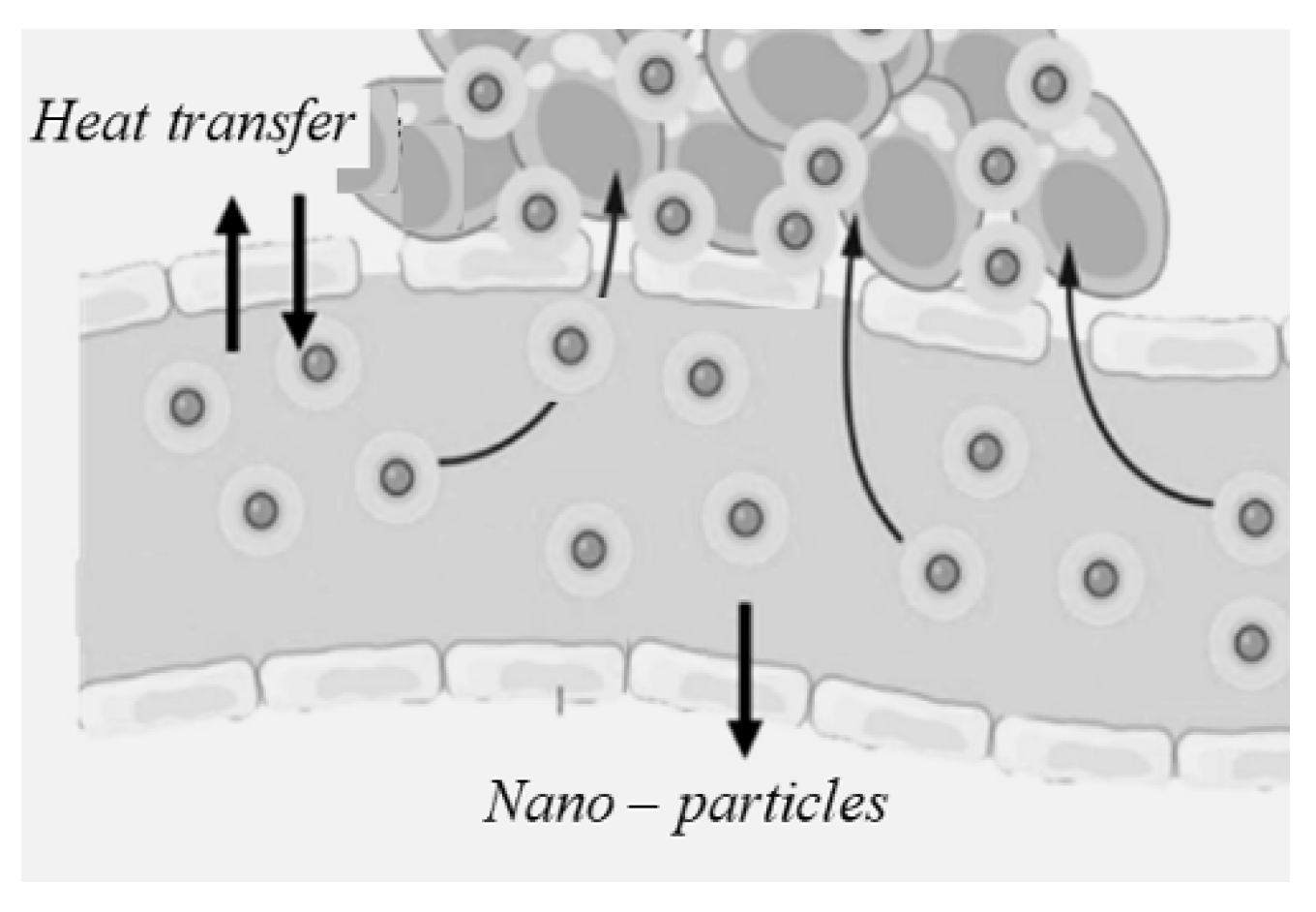

1. Introduction

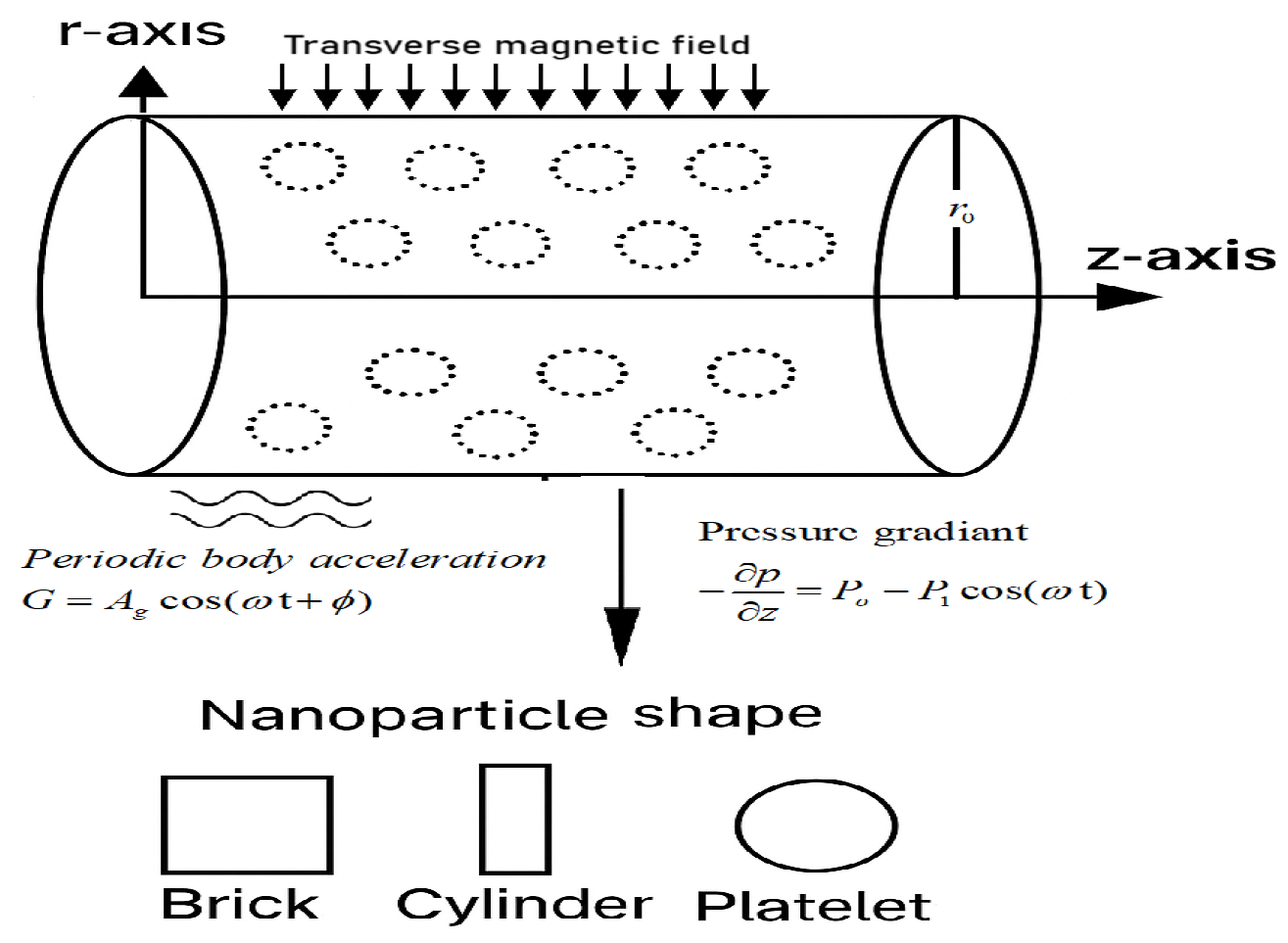

2. Research Design

3. Description and Mathematical Modeling of the Problem

Governing Equations

4. Non-Integer Order Analog of the Problem

5. Computational Framework

5.1. Computation for the Temperature Profiles

5.2. Computation for the Velocity Profiles

6. Heat Transfer Rate

7. Result Validation

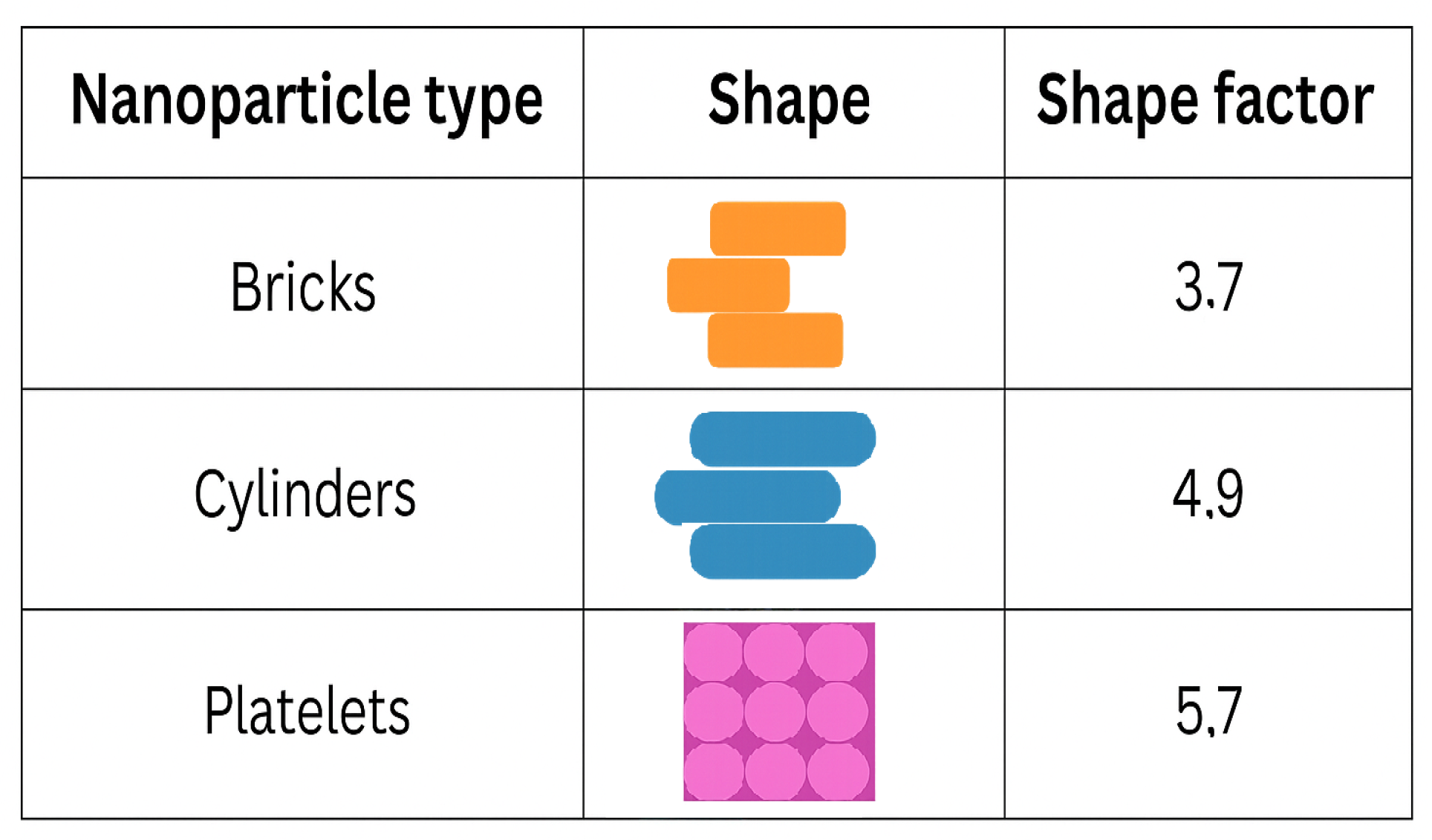

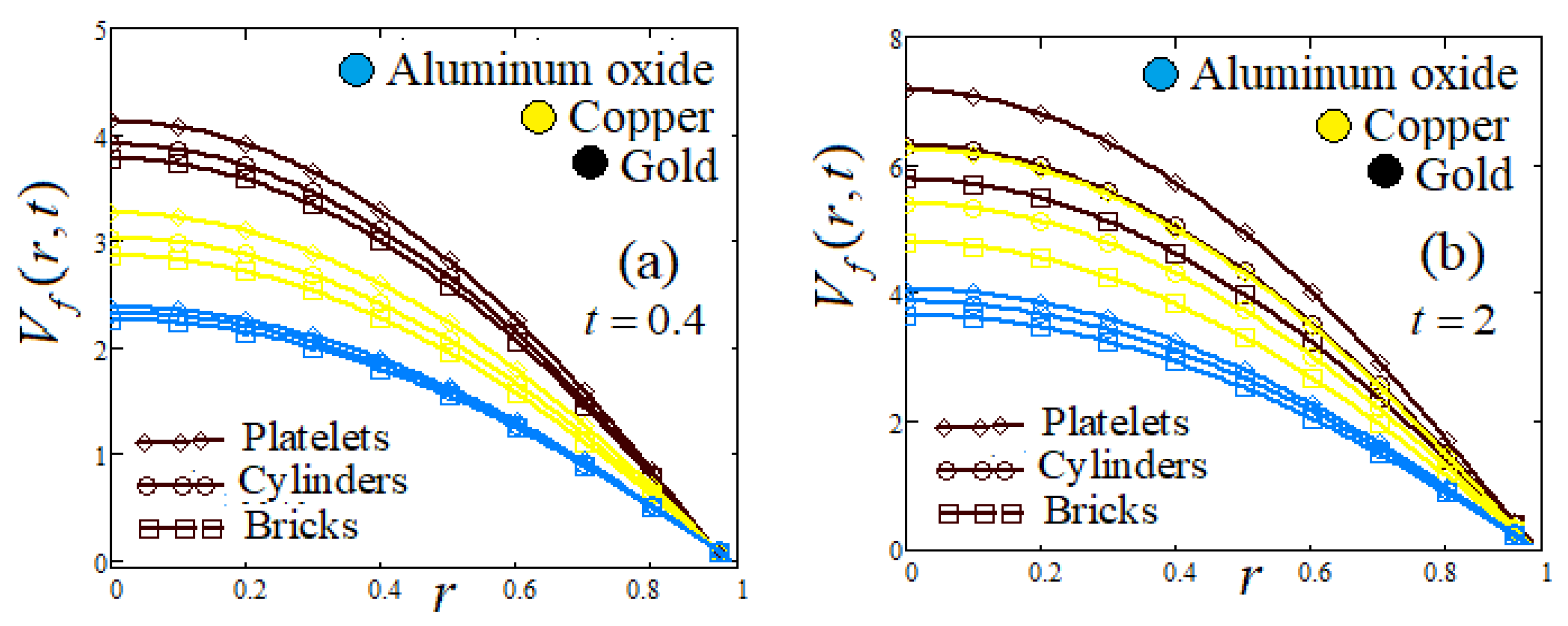

8. Graphs and Discussion

- (a)

- Influence of shapes of NPs

- (b)

- Influence of radial parameter

- (c)

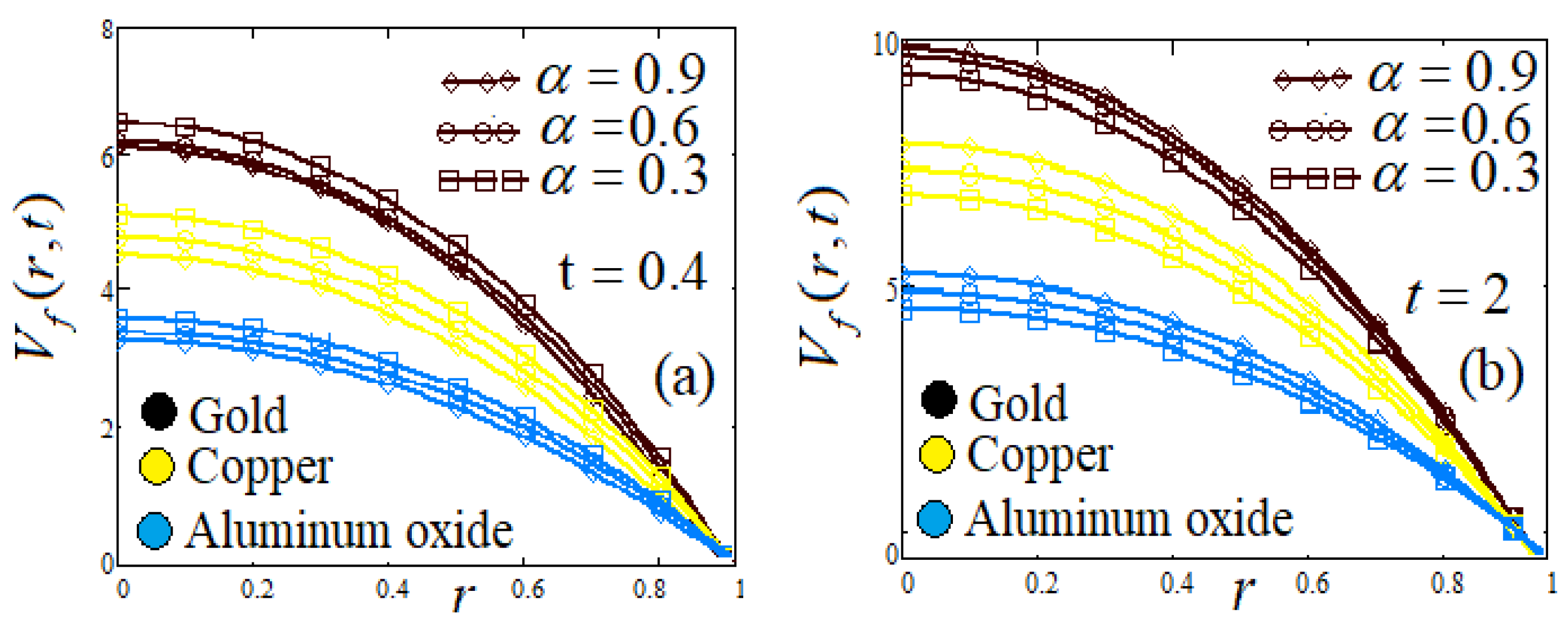

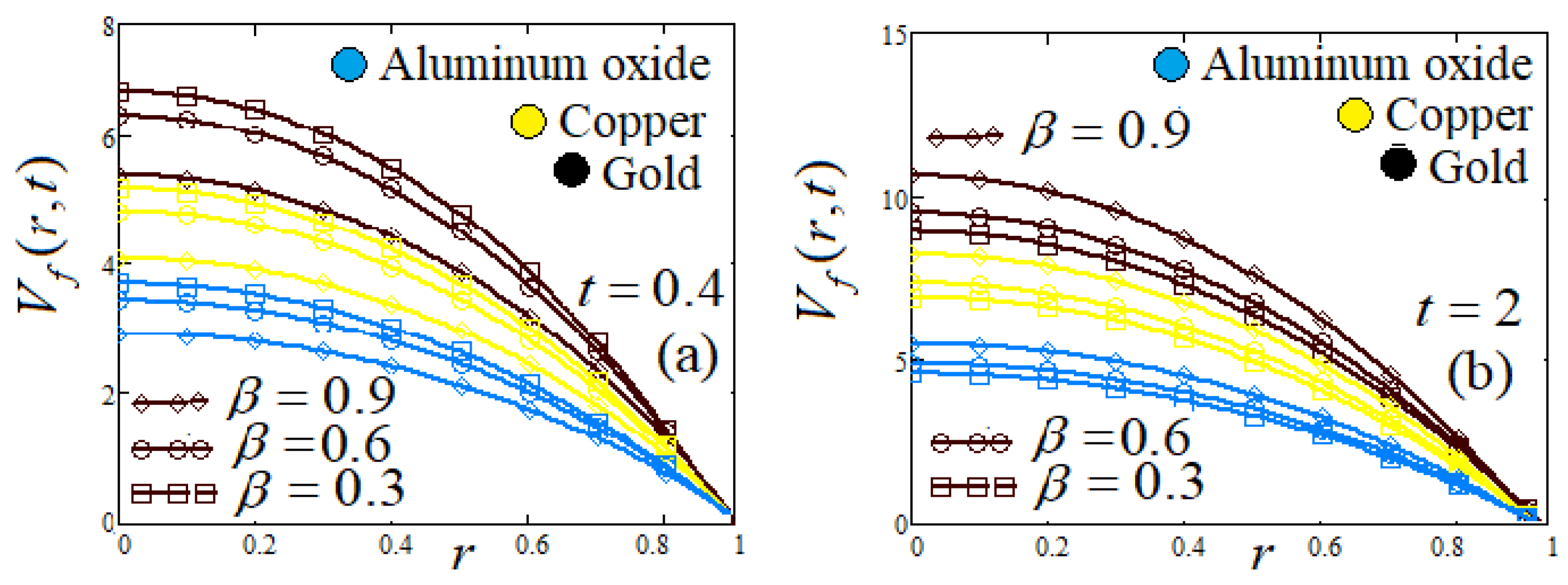

- Influence of fractional parameter α and β

- (d)

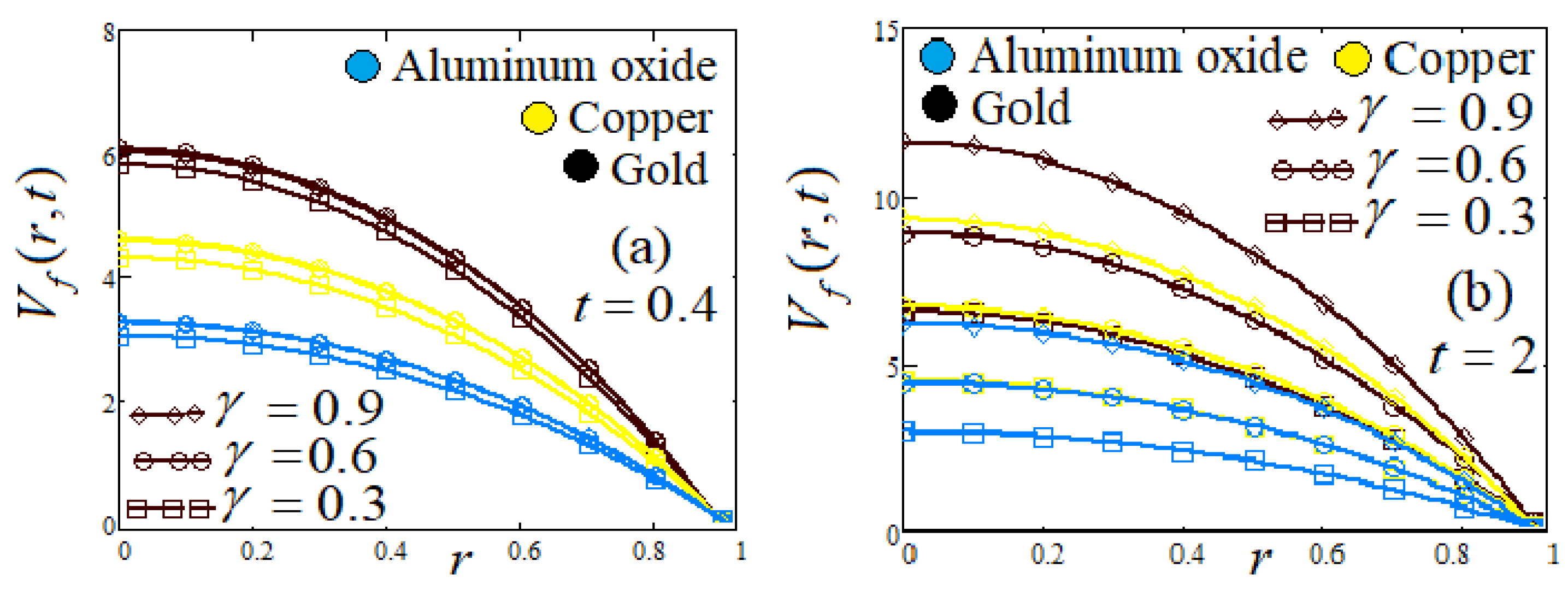

- Influence of fractional parameter

- (e)

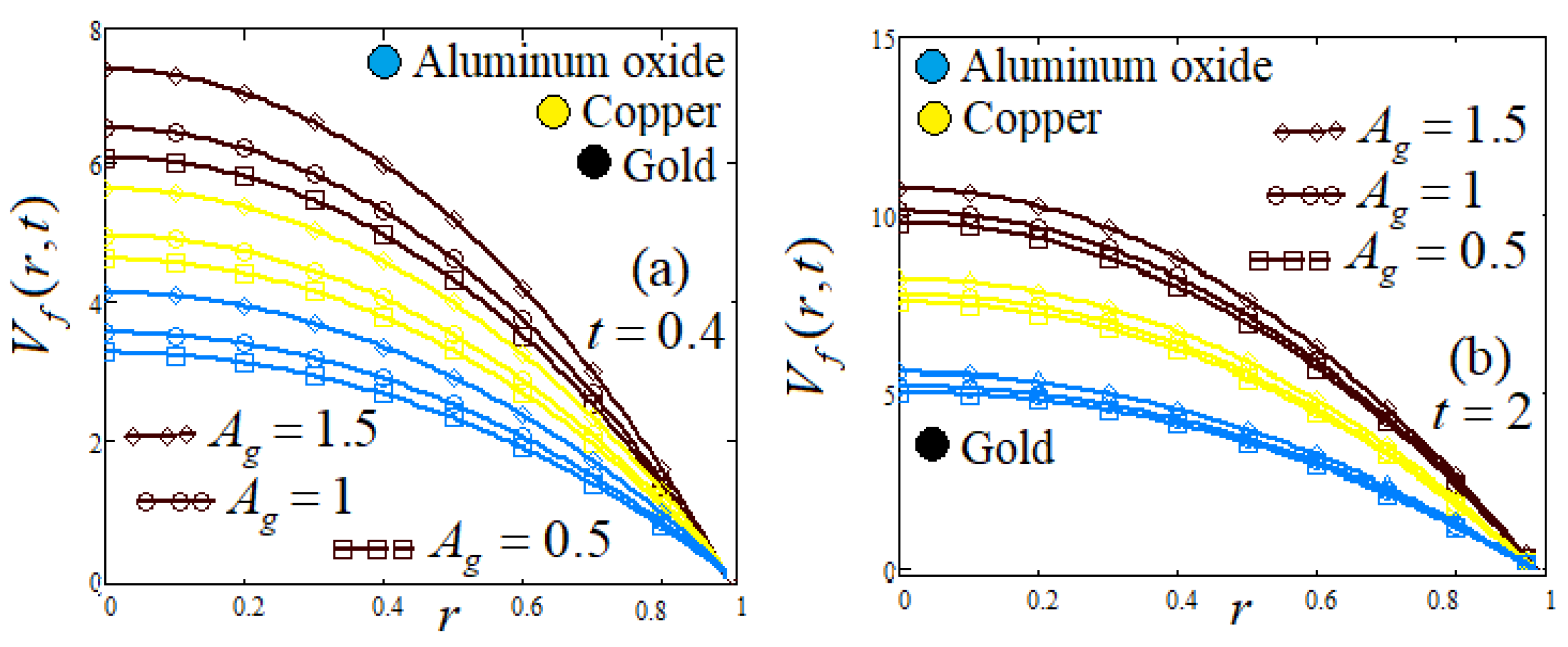

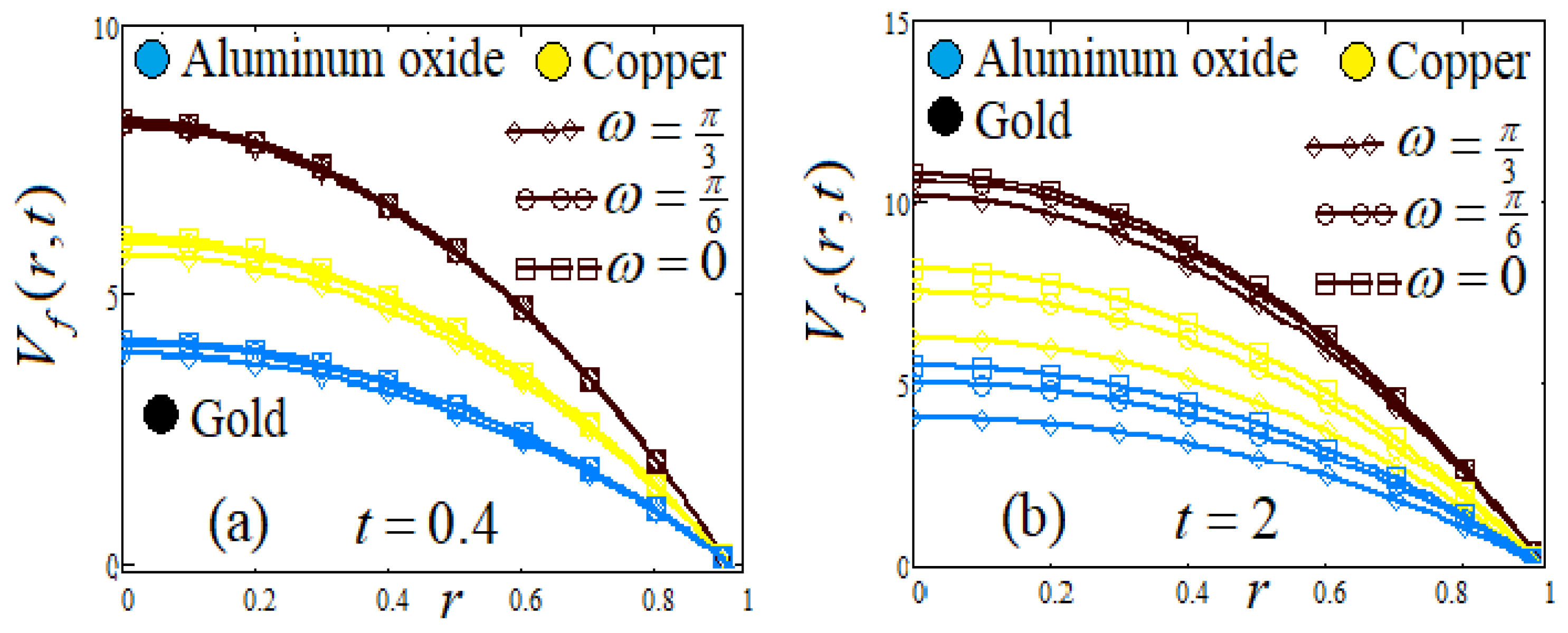

- Influence of amplitude and frequency of body acceleration ω

- (f)

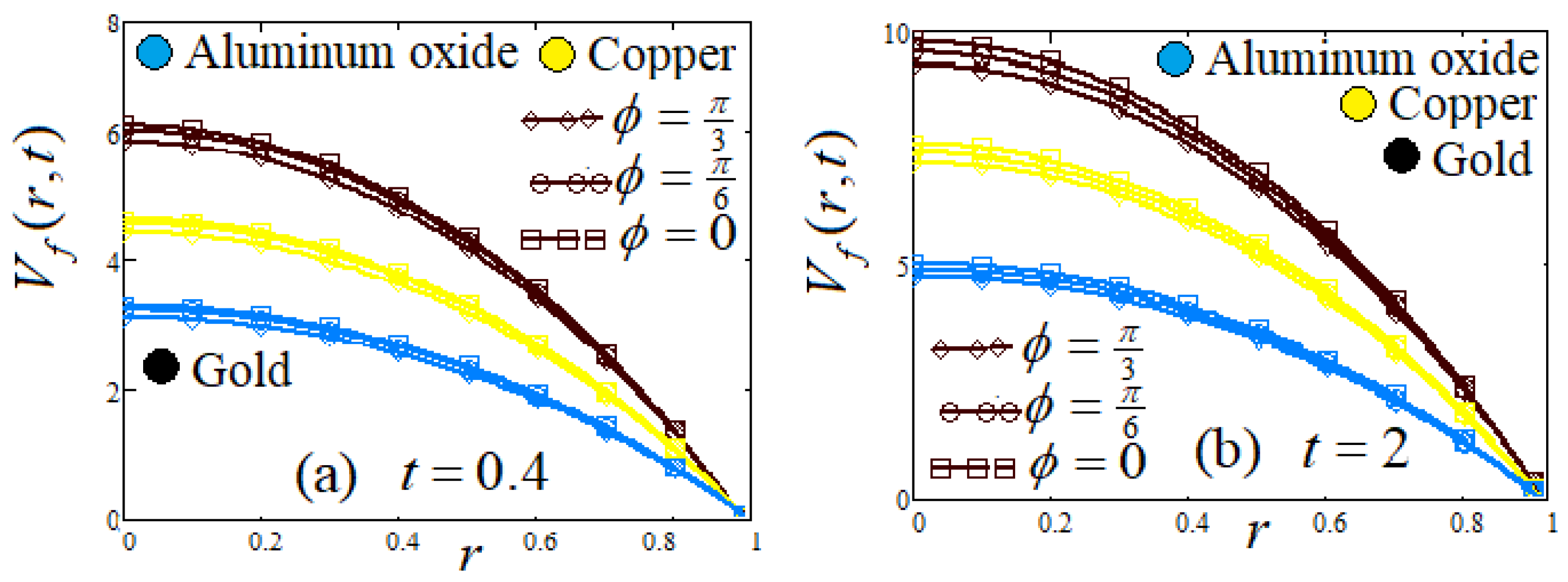

- Influence of lead angle ϕ

- (g)

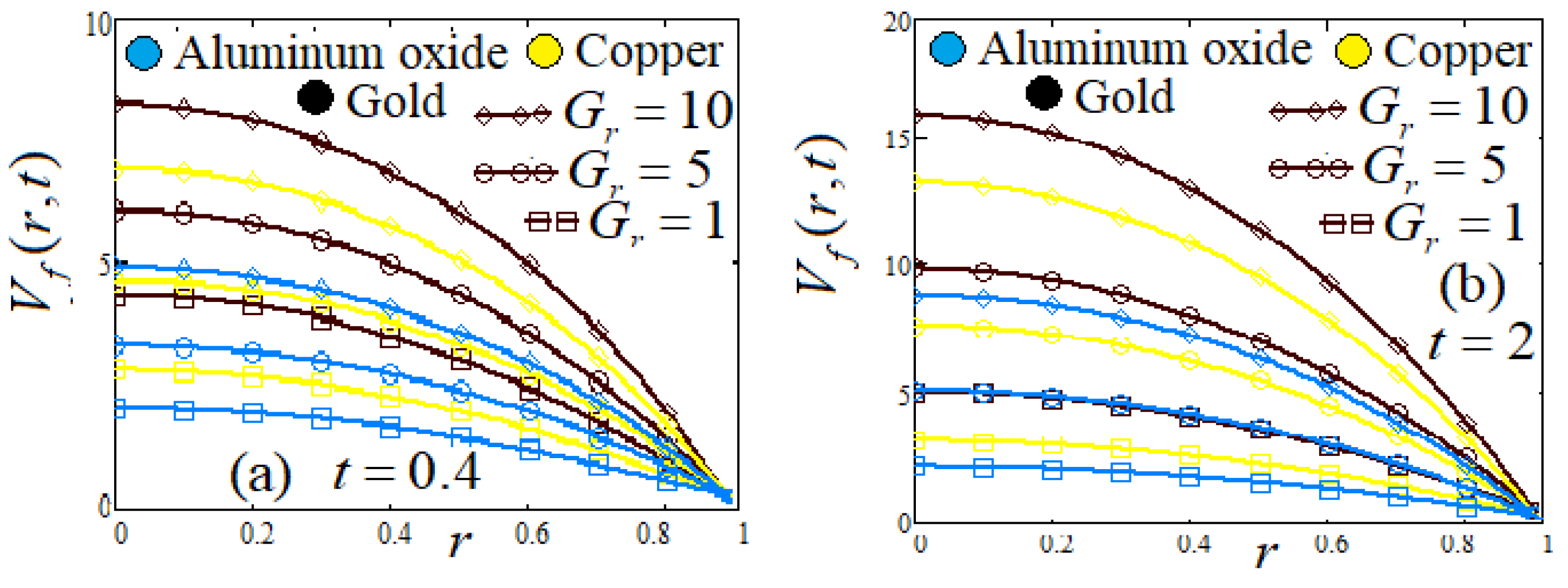

- Influence of Hartman number , and Grashof Number

- (h)

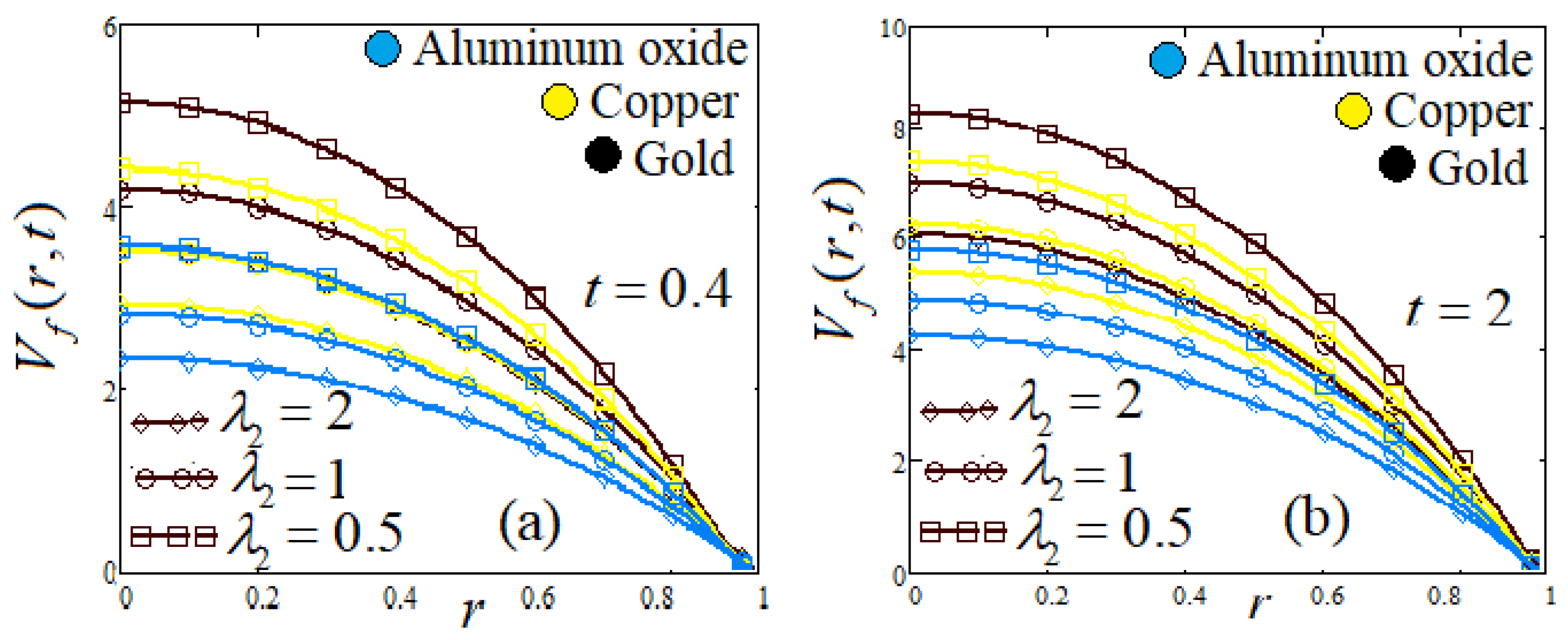

- Influence of relaxation time parameter and retardation time parameter

- (i)

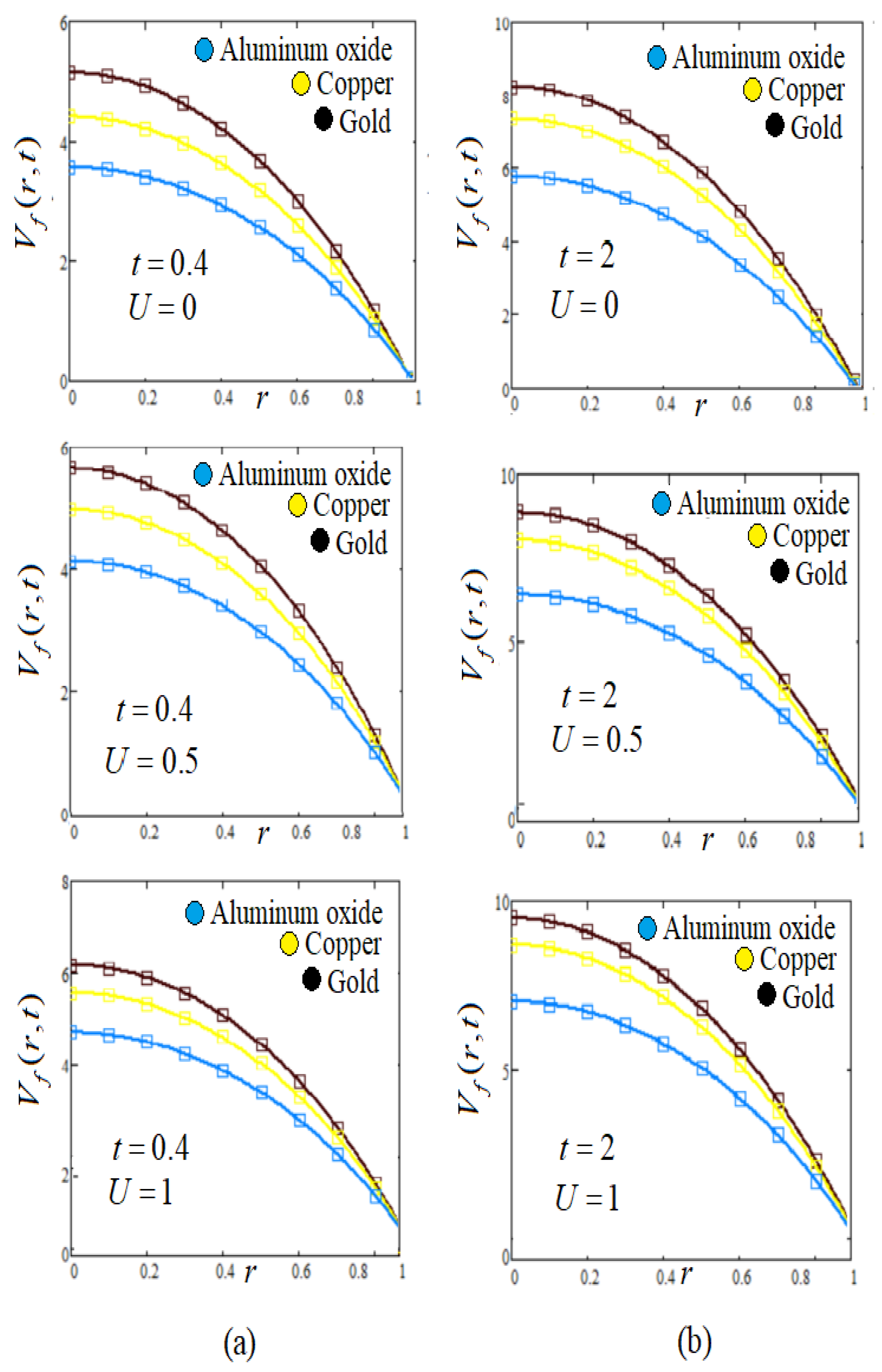

- Influence of slip effect U

- (j)

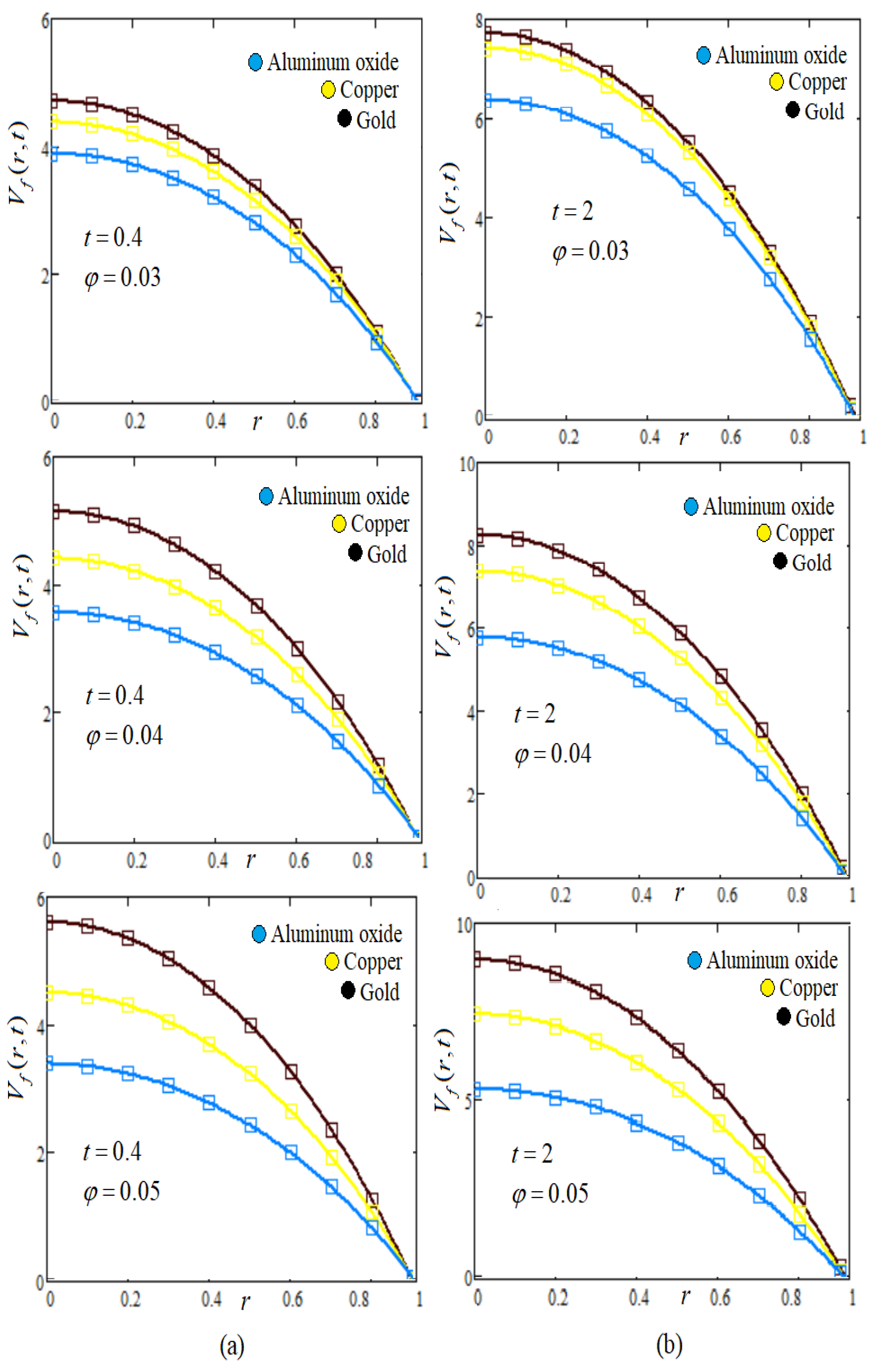

- Influence of NP volume fraction φ

8.1. Pairwise Comparative Analysis of NP Performance

8.1.1. vs.

8.1.2. vs.

8.1.3. vs.

9. Conclusions

10. Limitations in the Current Study and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NF | Nanofluid |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| MHD | Magnetohydrodynamics |

| FC | Fractional Calculus |

| ABC | Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo |

| LT | Laplace transform |

| FHT | Finite Hankel transform |

References

- Choi, S.U.S.; Eastman, J.A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. Fluids Eng. Div. 1995, 231, 99105. [Google Scholar]

- Peer, M.S.; Cascetta, M.; Migliari, L.; Petrollese, M. Nanofluids in Thermal Energy Storage Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2025, 18, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, V.; Cascetta, F.; Nardini, S. Application of nanofluids in industrial processes. The case of food processing. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 53, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, E.M.; Khaffaf, A.; Yasin, O.; Abu El-Rub, Z.; Al-Gharabli, S.; Al-Kouz, W.; Chamkha, A.J. Review of nanofluids and their biomedical applications. J. Nanofluids 2021, 10, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Bakr, A.F.; Kanagawa, T.; Abu-Nab, A.K. Analysis of doublet bubble dynamics near a rigid wall in ferroparticle nanofluids. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34, 102060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Nab, A.K.; Mamdouh, H.O.; Mohamed, K.G.; Abu-Bakr, A.F. Hydrodynamics and heat transfer of cavitation bubble in nanoparticles/water nanofluids based on the effects of variable surface tension and viscous forces. J. Nanofluids 2023, 12, 2044–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Jang, S.P. Effect of particle shape on suspension stability and thermal conductivities of water-based bohemite alumina nanofluids. Energy 2015, 90, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gu, H.; Fujii, M. Effective thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of nanofluids containing spherical and cylindrical nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 31, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: A comprehensive review for biologists. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Main, K.; Eberl, B.; McDaniel, D.; Tikadar, A.; Paul, T.C.; Khan, J.A. Nanoparticles shape effect on viscosity and thermal conductivity of ionic liquids based nanofluids. In Proceedings of the 5th Thermal and Fluids Engineering Conference (TFEC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–8 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, E.W.; Benis, A.M.; Gilliland, E.R.; Sherwood, T.K.; Salzman, E.W. Pressure-flow relations of human blood in hollow fibers at low flow rates. J. Appl. Physiol. 1965, 20, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, K.; Intaglietta, M.; Tartakovsky, D.M. Non-Newtonian flow of blood in arterioles: Consequences for wall shear stress measurements. Microcirculation 2014, 21, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Sankar, D.S.; Hemalatha, K.; Yatim, Y. Mathematical analysis of Casson fluid model for blood rheology in stenosed narrow arteries. J. Appl. Math. 2013, 2013, 583809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, G.B. Viscoelasticity of human blood. Biophys. J. 1972, 12, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeleswarapu, K.K.; Kamaneva, M.V.; Rajagopal, K.R.; Antaki, J.F. The flow of blood in tubes:Theory and experiment. Mech. Res. Commun. 1998, 25, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, G.B. Rheological parameters for the viscosity, viscoelasticity and Thixotropy of blood. Biorheology 1979, 16, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.A.; Awan, A.U.; Khan, R.; Tlili, I.; Farooq, M.U.; Salah, B.; Chung, J.D. Free convection Hartmann flow of a viscous fluid with damped thermal transport through cylindrical tube. Chin. J. Phys. 2022, 80, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Imran, M.; Imran, M.A.; Khan, I.; Nisar, K.S. Natural convection flow of a second grade fluid in an infinite vertical cylinder. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Shah, N.A.; Tassaddiq, A.; Mustapha, N.; Kechil, S.A. Natural convection heat transfer in an oscillating vertical cylinder. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 0188656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Shah, N.A.; Vieru, D. Natural convection with damped thermal flux in a vertical circular cylinder. Chin. J. Phys. 2018, 56, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, L.; Hussain, A.; Fernandez, G.U.; Akbar, S.; Rehman, A.; Sherif, E.S.M. Thermal enhancement and numerical solution of blood nanofluid flow through stenotic artery. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Gao, L.; Chen, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; Hu, K. Nanoparticles: A new approach to upgrade cancer diagnosis and treatment. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, W.F.W.; Mohamad, A.Q.; Jiann, L.Y.; Shafie, S. Unsteady natural convection flow of blood Casson nanofluid (Au) in a cylinder: Nano-cryosurgery applications. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, A.; Foong, O.M.; Aamina, A.; Khan, N.; Farhad, A.; Khan, N. Generalized model of blood flow in a vertical tube with suspension of gold nanomaterials: Applications in the cancer therapy. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2020, 65, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, M.; Lauga, E.; Stone, H. Microfluidics: The No-Slip Boundary Condition; Springer Handbooks; Tropea, C., Yarin, A.L., Foss, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nubar, Y. Blood fow, slip and viscometry. Biophys. J. 1971, 11, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.A.; Sarwar, S.; Imran, M. Effects of slip on free convection flow of Casson fluid over an oscillating vertical plate. Bound. Value Probl. 2016, 2016, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saqib, M.; Ali, F.; Khan, I.; Sheikh, N.A. Heat and mass transfer phenomena in the flow of Casson fluid over an infinite oscillating plate in the presence of first-order chemical reaction and slip effect. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 30, 2159–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qi, H.; Xu, H.; Jiang, X. Transient electroosmotic slip flow of fractional Oldroyd-B fluids. Microfluid. Nanofluid 2017, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.A.; Wang, X.; Qi, H.; Wang, S.; Hajizadeh, A. Transient electro-osmotic slip flow of an Oldroyd-B fluid with time fractional Caputo-Fabrizio derivative. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2019, 5, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma, R.; Selvi, R.T.; Ponalagusamy, R. Effects of slip and magnetic field on the pulsatile flow of a Jefrey fluid with magnetic NPs in a stenosed artery. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2019, 134, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma, R.; Ponalagusamy, R.; Selvi, R.T. Mathematical modeling of electro hydrodynamic non-Newtonian fluid flow through tapered arterial stenosis with periodic body acceleration and applied magnetic field. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 362, 124453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F. Fractional calculus: Some basic problems in continuum and statistical mechanics. In Fractals and Fractional Calculus in Continuum Mechanics; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1997; Volume 378, pp. 291–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, K.B.; Spanier, J. The Fractional Calculus; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Baleanu, D.; Jajarmi, A.; Mohammadi, H.; Rezapour, S. A new study on the mathematical modelling of human liver with Caputo-Fabrizio fractional derivative. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2020, 134, 109705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awrejcewicz, J.; Zafar, A.A.; Kudra, G.; Riaz, M.B. Theoretical study of the blood flow in arteries in the presence of magnetic particles and under periodic body acceleration. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2020, 140, 110204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, W.F.W.; Mohamad, A.Q.; Jiann, L.Y.; Shafie, S. Mathematical Modelling on Pulsative MHD Blood Casson Nanofluid in Slip and Porous Capillaries for Nano-cryosurgery with Caputo-Fabrizio Approach. Braz. J. Phys. 2025, 55, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldroyd, J.G. On the Formulation of Rheological Equations of State. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1950, 200, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, D.G.; Abdulhameed, M.; Adamu, G.T.; Hassan, U.; Kaurangini, M.L. Construction of the exact solution of blood flow of Oldroyd-B fluids through arteries with effects of fractional derivative magnetic field and heat transfer. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2022, 22, 2250068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, J. Drug Delivery: Tracer NPs May Predict Which Tumors Will Respond to Nanomedicine. 2015. Available online: https://cen.acs.org/articles/93/i46/New-Technique-Help-Personalize-Nanomedicine.html (accessed on 19 November 2015).

- Mandal, P.K. An unsteady analysis of non-Newtonian blood flow through tapered arteries with astenosis. Int. J. Nonlin. Mech. 2005, 40, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellahi, R.; Hassan, M.; Zeeshan, A. Shape effects of nanosize particles in Cu-H20 nanofluid on entropy generation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 81, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.L.; Crosser, O.K. Thermal conductivity of heterogeneous two-component systems. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 1962, 1, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A.; Baleanu, D. New fractional derivatives with non-local and non-singular kernel: Theory and applications to heat transfer model. Thermal Sci. 2016, 20, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, L.; Bhatta, D. Integral Transforms and Their Applications, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C.F.; Hartley, T.T. Generalized functions for fractional calculus. Phys. Rev. 2013, 25, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehfest, H. Numerical Inversion of Laplace Transform. Commun. ACM 1970, 13, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, M.M.; Hurd, W.J.; Fortune, E.; Lugade, V.; Kaufman, K.R. Accelerations of the waist and lower extremities over a range of gait velocities to aid in activity monitor selection for field-based studies. J. Appl. Biomech. 2014, 30, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chinyoka, T.; Makinde, O.D. Computational dynamics of arterial blood flow in the presence of magnetic field and thermal radiation therapy. Adv. Math. Phys. 2014, 2014, 915640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Unit | Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity of the fluid | ||

| K | Temperature of the fluid | |

| K | Temperature at wall | |

| K | Temperature of atmosphere | |

| Magnetic field | ||

| Thermal conductivity of base fluid | ||

| Thermal conductivity of Nanofluid | ||

| Thermal conductivity of nanoparticles | ||

| Constant amplitude | ||

| Pulsatile component’s amplitude | ||

| Density of fluid | ||

| Density of nanofluid | ||

| Viscosity of nanofluid | ||

| Viscosity of fluid | ||

| Kinematic viscosity of the nanofluid | ||

| Thermal expansion coefficient of base fluid | ||

| Thermal expansion coefficient of nanofluid | ||

| Thermal expansion coefficient of nanoparticles | ||

| s | Relaxation time parameter | |

| s | Retardation time parameter | |

| Frequency of body acceleration | ||

| Electrical conductivity of base fluid | ||

| Electrical conductivity of nanofluid | ||

| Electrical conductivity of nanoparticles | ||

| rad | Lead angle | |

| Amplitude of body acceleration | ||

| no units | Fractional parameter | |

| no units | Fractional parameter | |

| no units | Fractional parameter | |

| no units | Hartman number | |

| no units | Prandtl number | |

| no units | Solid volume fraction of nanoparticles | |

| m | no units | Shapes parameter of nanoparticles |

| Physical Properties | Blood | Al2O3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (J/kgK) | 3594 | 128.8 | 385 | 686.2 |

| (kg/ | 1063 | 19,300 | 8933 | 4250 |

| K (W/mK) | 0.492 | 314.4 | 400 | 8.95 |

| ( | 0.18 | 1.4 | 1.67 | 0.9 |

| (s/m) | 0.67 | 4.11 | 5.17 |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for | Enhancement | for | Enhancement | for | Enhancement | for | Enhancement | for Al2O3 | Enhancement | for Al2O3 | Enhancement | |

| 1.214 | - | 0.345 | - | 1.214 | - | 0.345 | - | 1.214 | - | 0.345 | - | |

| 1.306 | 7.5% | 0.377 | 9 % | 1.303 | 7.3 % | 0.376 | 8.7% | 1.288 | 6% | 0.372 | 7.7 % | |

| 1.398 | 15.1% | 0.409 | 18.5 % | 1.390 | 14.3 % | 0.407 | 17.9 % | 1.363 | 12 % | 0.399 | 15.6 % | |

| 1.502 | 23.4 % | 0.442 | 29.4% | 1.483 | 23.2 % | 0.444 | 28.3 % | 1.452 | 19.6 % | 0.430 | 26.4% | |

| 1.607 | 32.3% | 0.486 | 40.8 % | 1.596 | 31 % | 0.481 | 39.4 % | 1.542 | 27.1% | 0.461 | 33.6% | |

| 1.725 | 42% | 0.532 | 54.2 % | 1.711 | 40.9 % | 0.521 | 51 % | 1.638 | 34.9% | 0.497 | 44% |

| Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Increasing) | Velocity | Velocity | Temperature | Temperature |

| of Fluid | of Fluid | of Fluid | of Fluid | |

| r | decreases | decreases | - | - |

| decreases | increases | - | - | |

| decreases | increases | - | - | |

| increases | increases | - | - | |

| decreases | decreases | - | - | |

| decreases | decreases | - | - | |

| increases | increases | - | - | |

| increases | increases | - | - | |

| decreases | decreases | - | - | |

| decreases | decreases | - | - | |

| increases | increases | - | - | |

| increases | increases | increases | increases |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shahzaib, M.; Zafar, A.A. Theoretical Analysis of Blood Rheology as a Non-Integer Order Nanofluid Flow with Shape-Dependent Nanoparticles and Thermal Effects. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111854

Shahzaib M, Zafar AA. Theoretical Analysis of Blood Rheology as a Non-Integer Order Nanofluid Flow with Shape-Dependent Nanoparticles and Thermal Effects. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111854

Chicago/Turabian StyleShahzaib, Muhammad, and Azhar Ali Zafar. 2025. "Theoretical Analysis of Blood Rheology as a Non-Integer Order Nanofluid Flow with Shape-Dependent Nanoparticles and Thermal Effects" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111854

APA StyleShahzaib, M., & Zafar, A. A. (2025). Theoretical Analysis of Blood Rheology as a Non-Integer Order Nanofluid Flow with Shape-Dependent Nanoparticles and Thermal Effects. Symmetry, 17(11), 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111854