Research on Enterprise Public Opinion Crisis Response Strategies in the Context of Information Asymmetry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Emotions in Public Opinion Dissemination

2.2. Research on the Formation and Spread of Panic

2.3. The Application of Tipping Point Theory in the Dissemination of Public Opinion

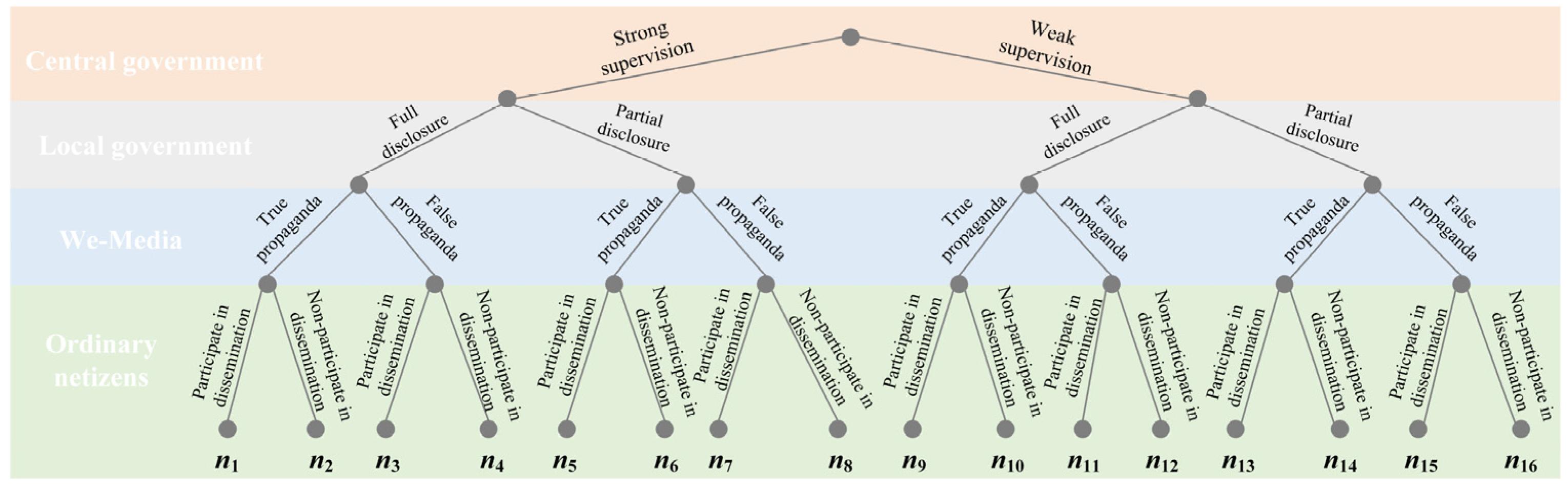

3. Multi-Agent Evolutionary Game Model

3.1. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Strategies in the Context of Information Asymmetry

3.2. Basic Assumptions

3.3. Model Construction and Analysis

3.4. Analysis of the Stability Conditions for Strategy Combinations

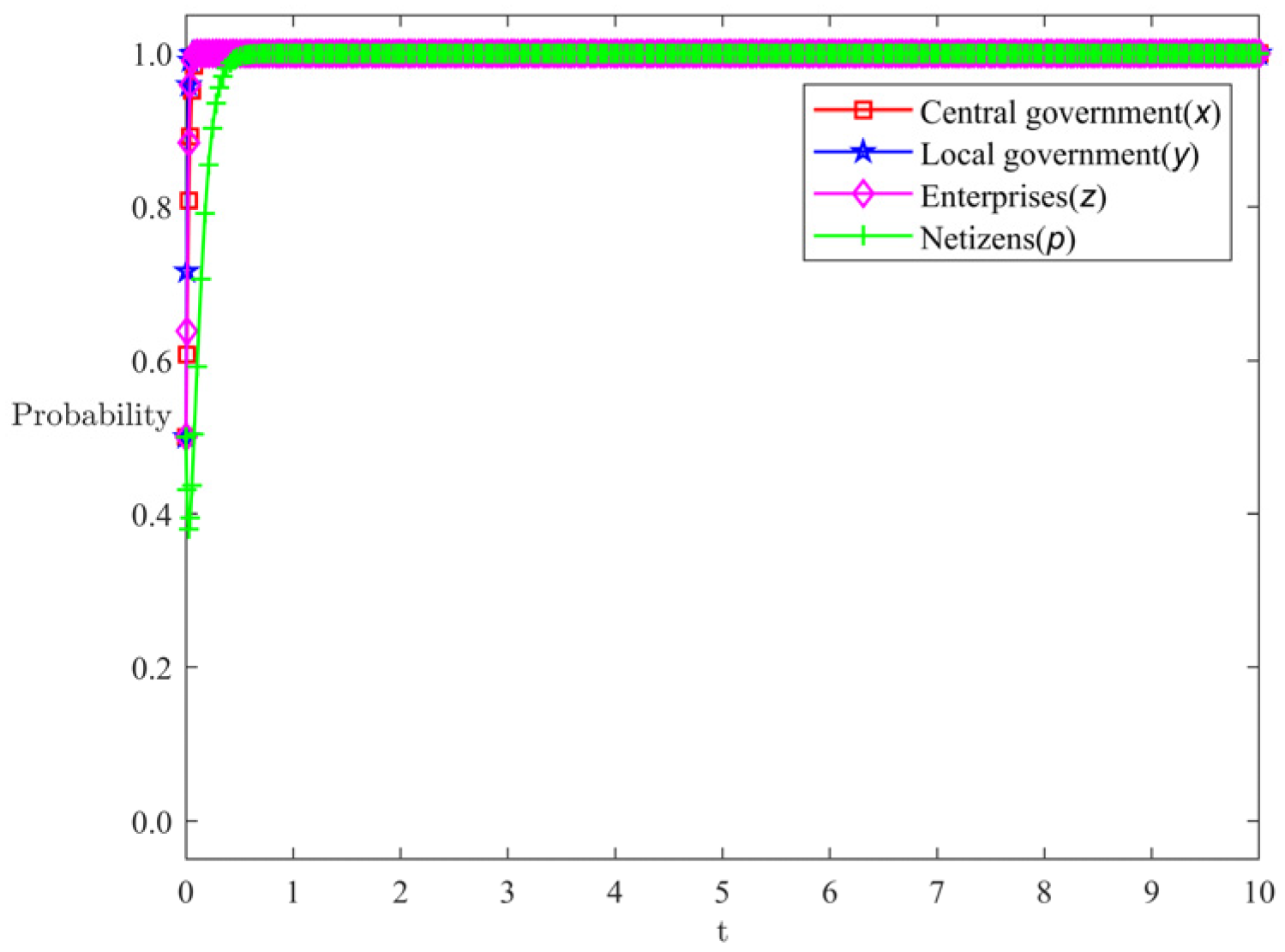

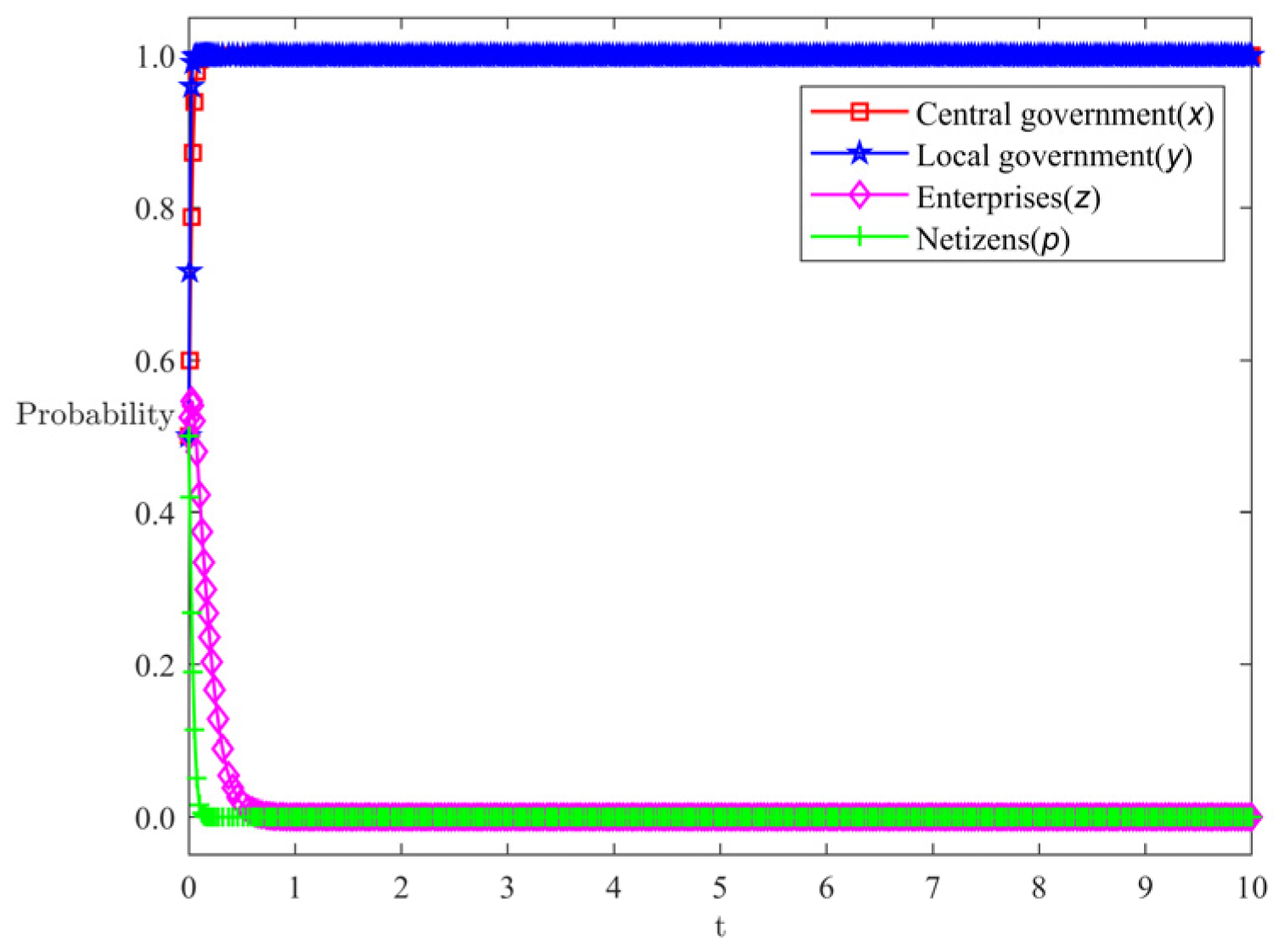

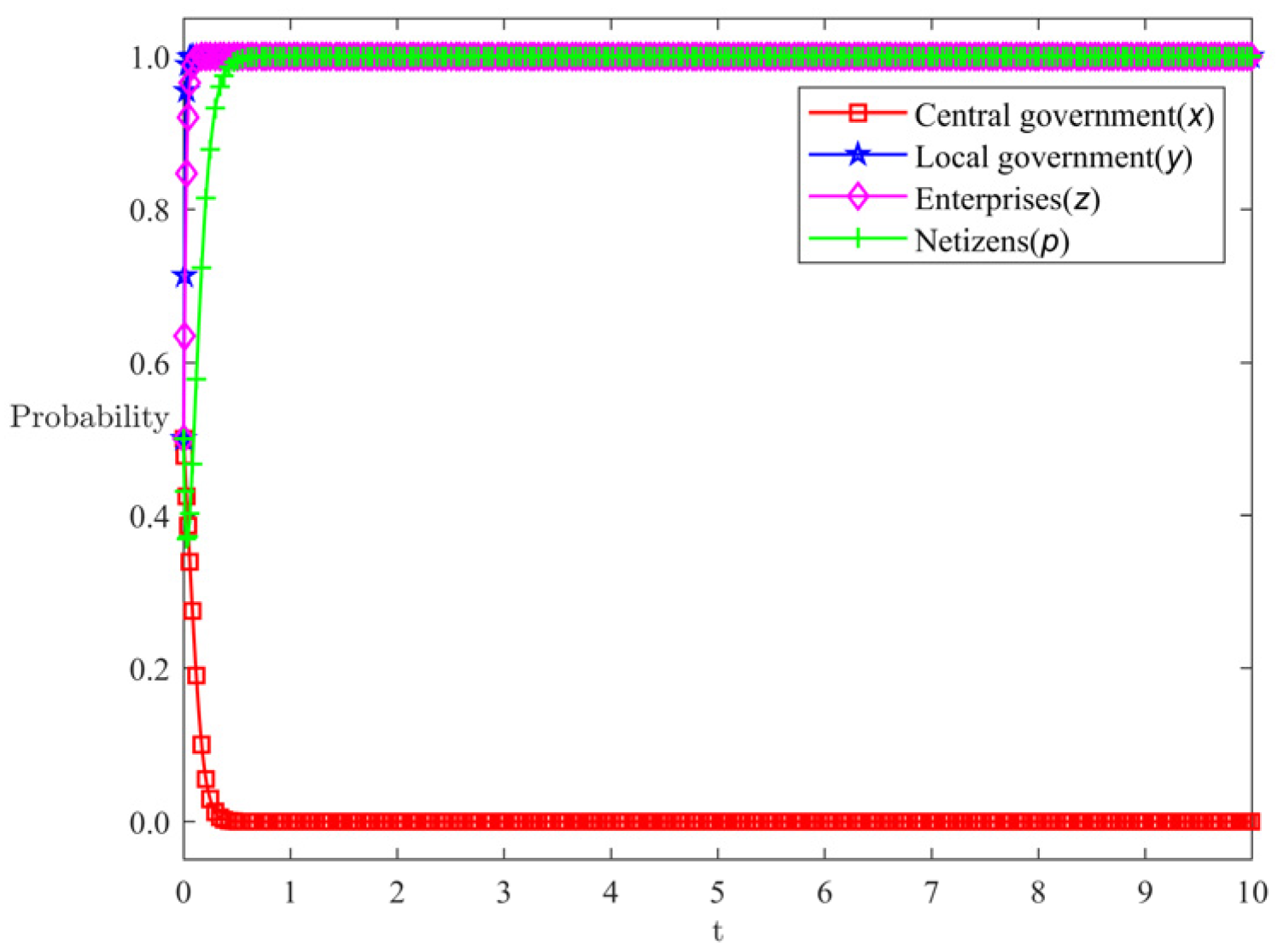

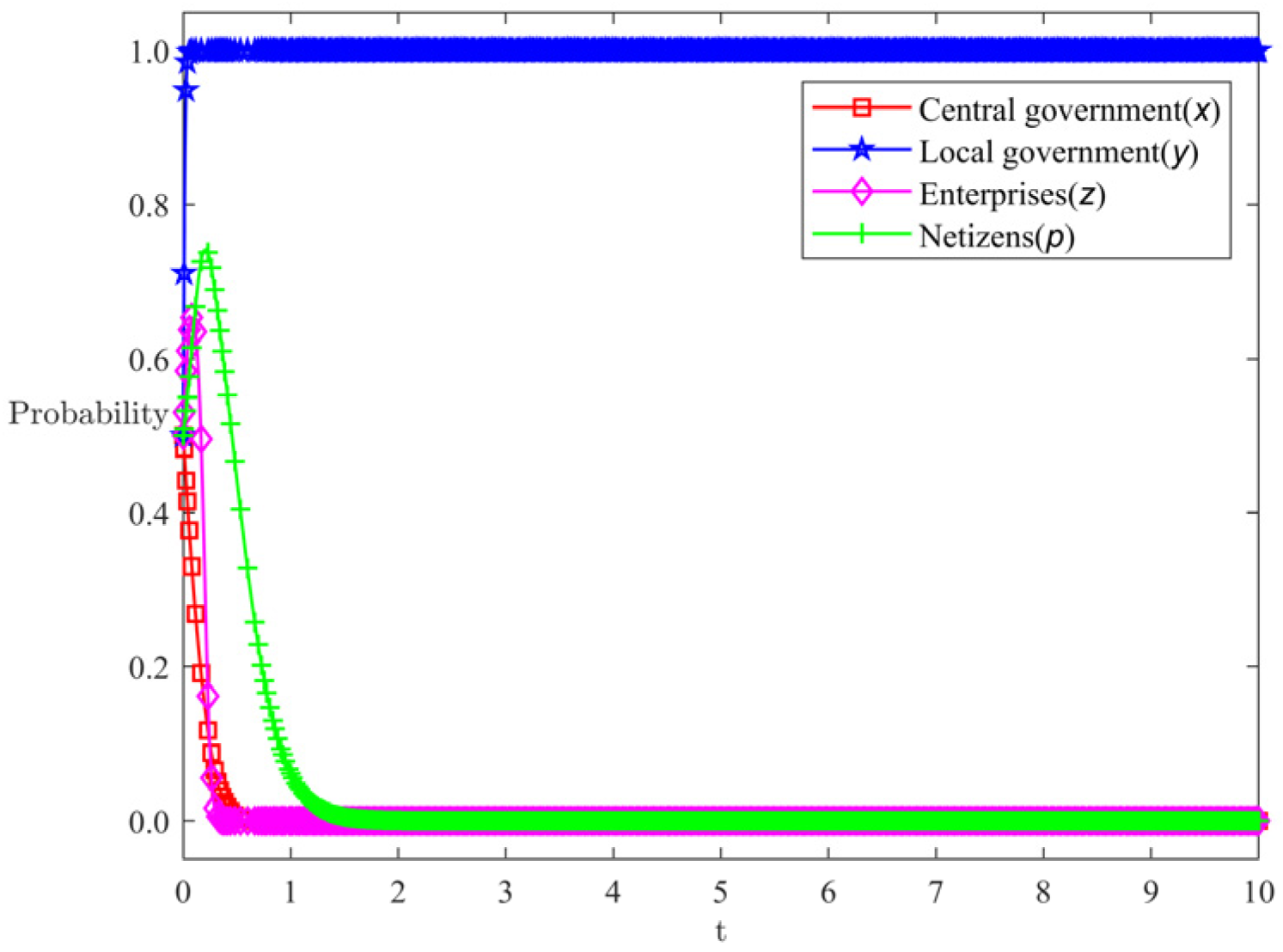

4. Simulation Analysis

4.1. Initial Assignment for Simulation

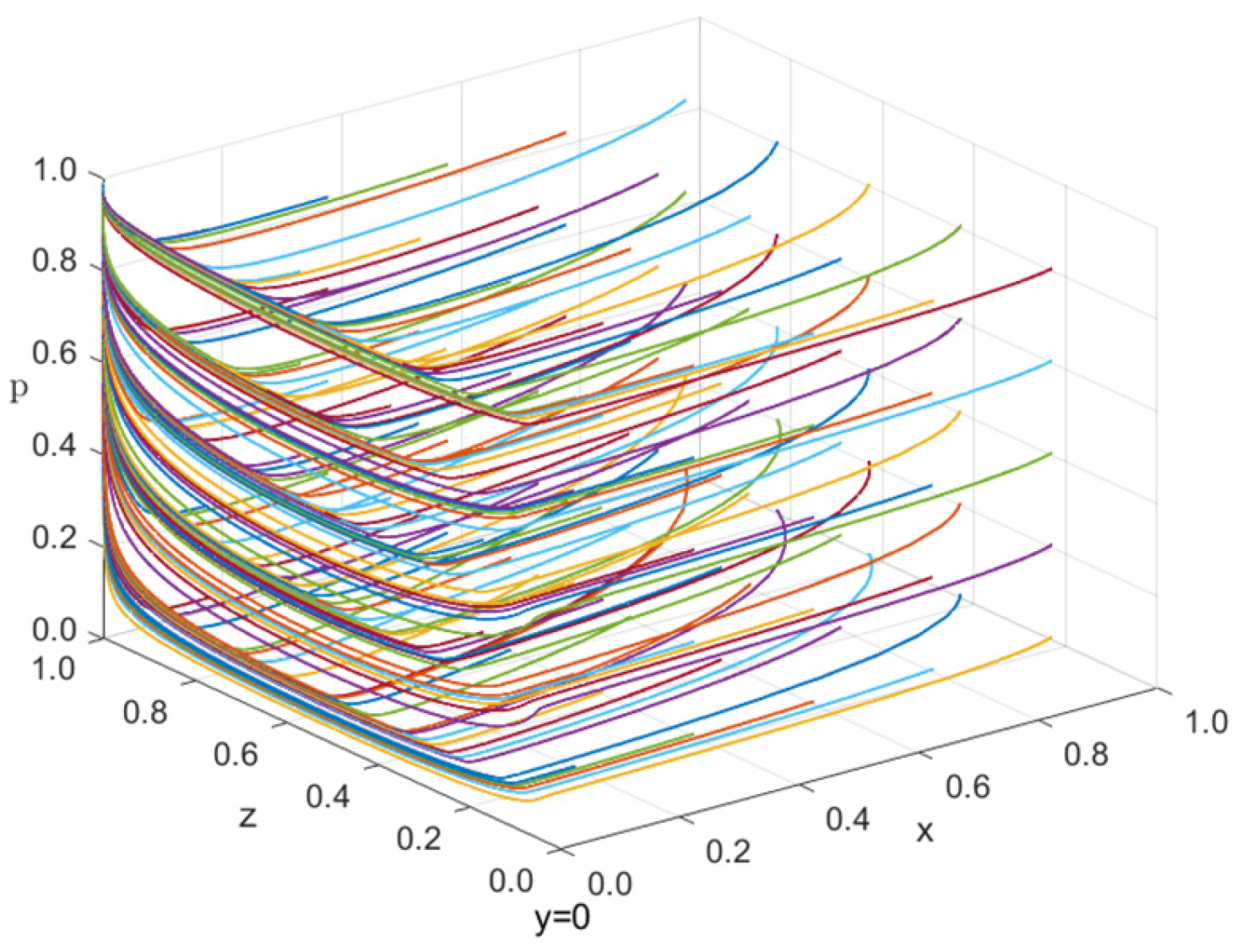

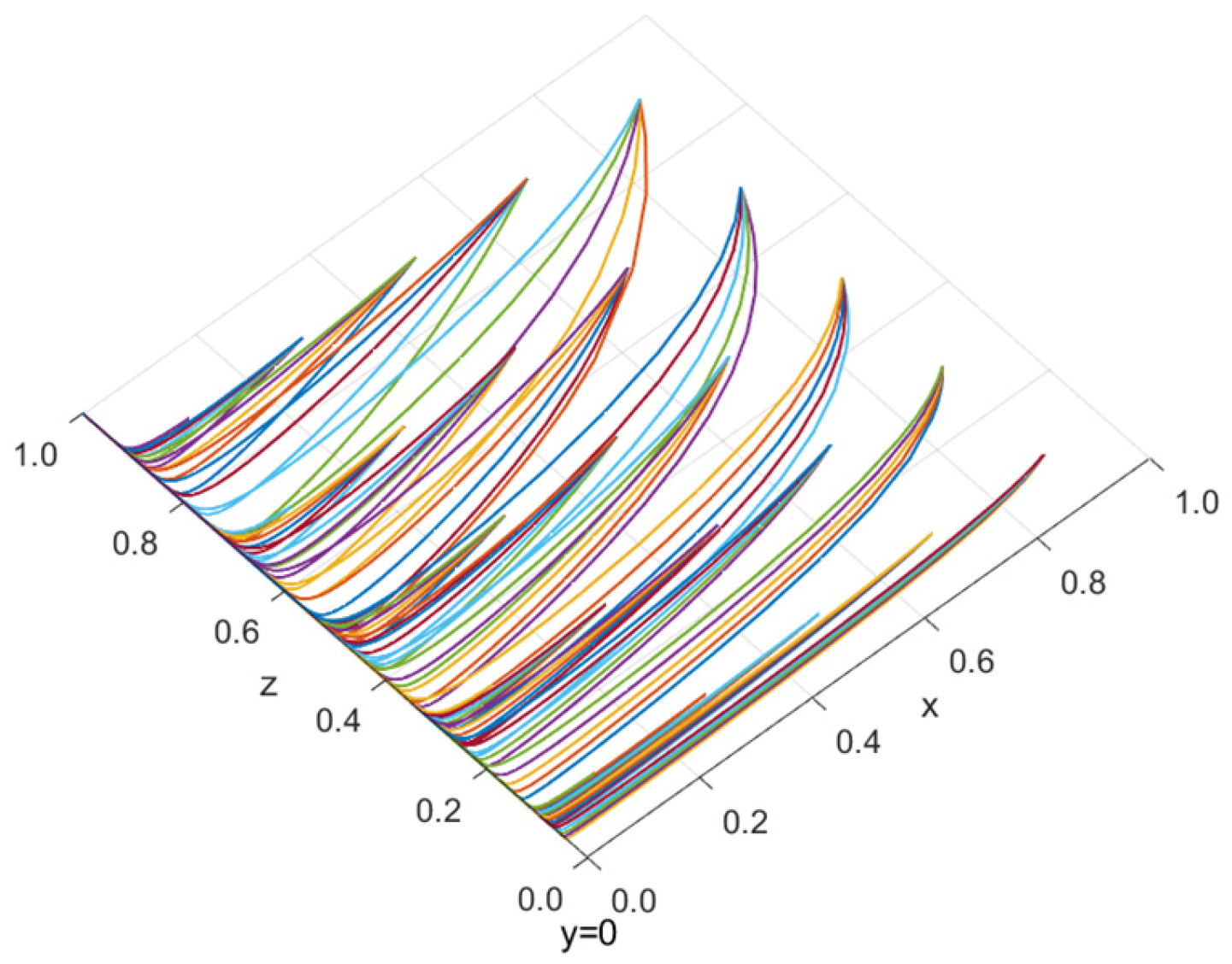

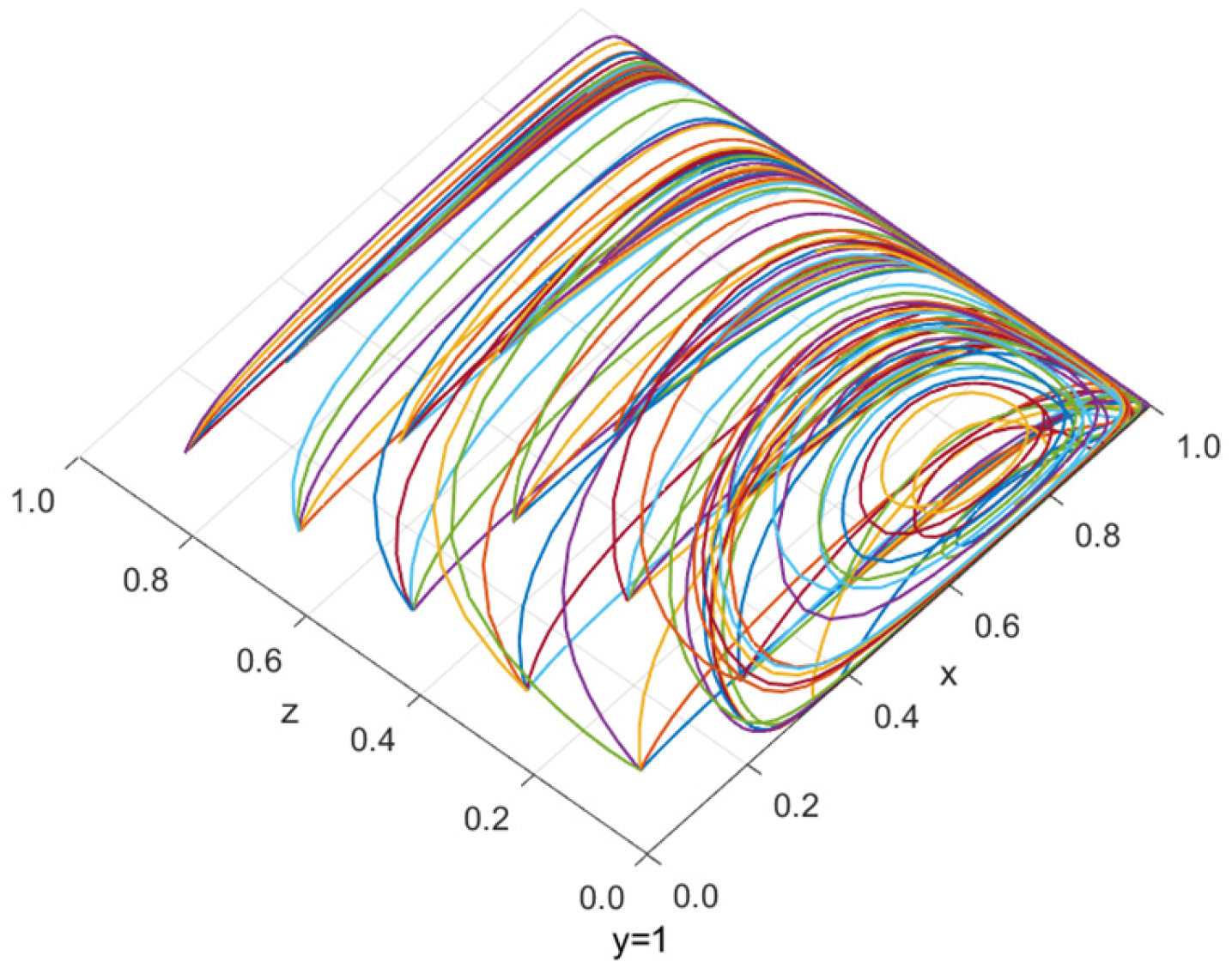

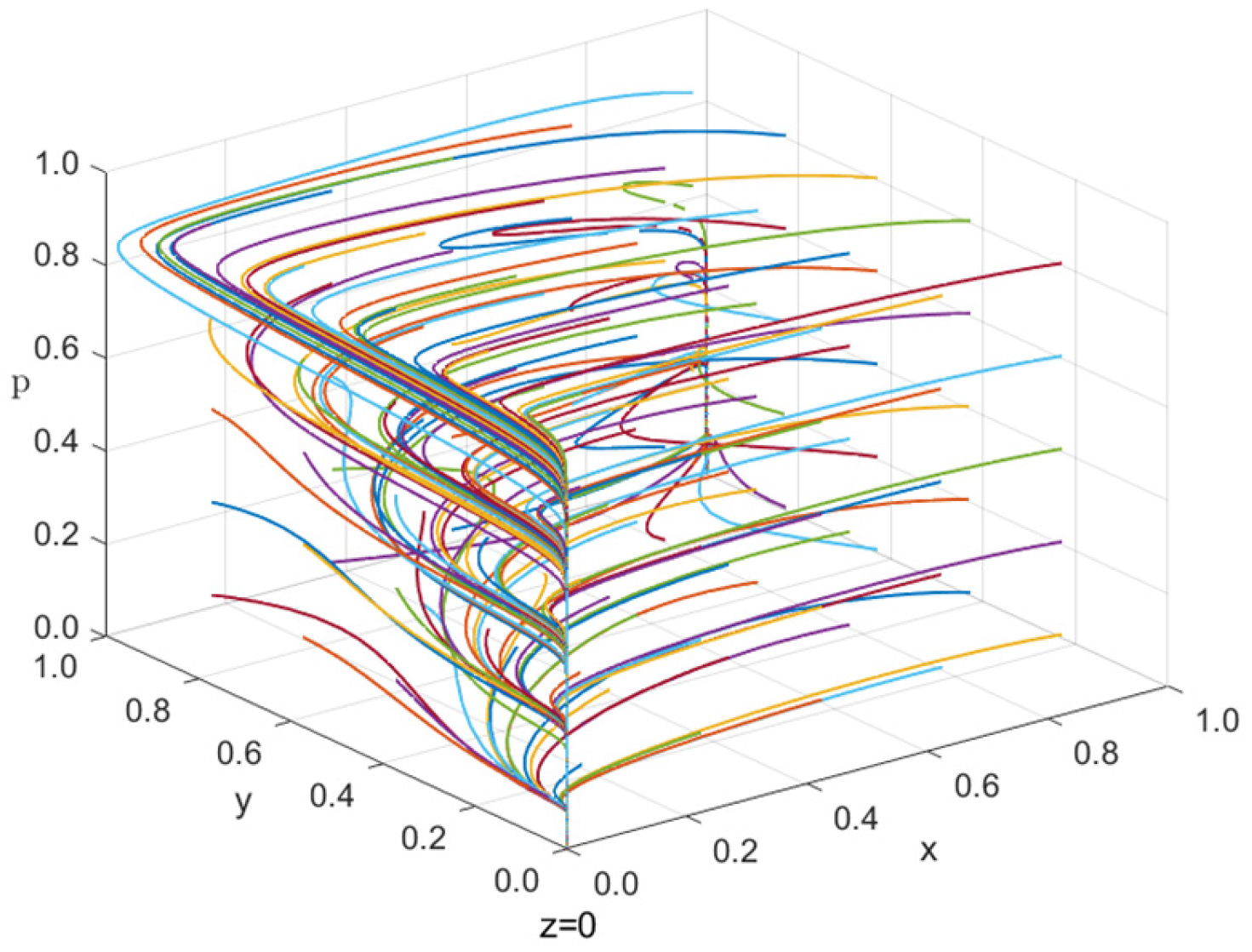

4.2. The Influence of Public Panic on Evolutionary Equilibrium

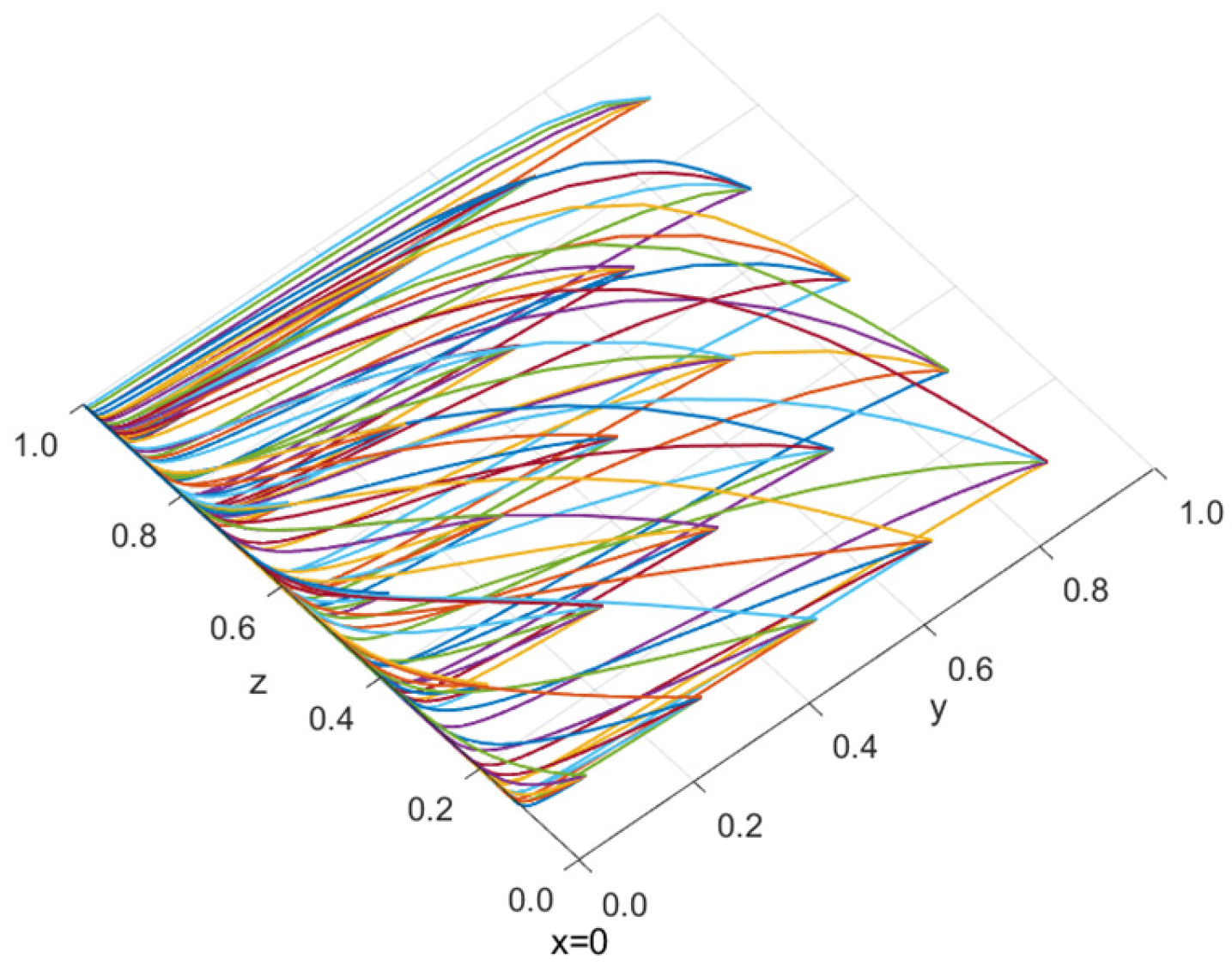

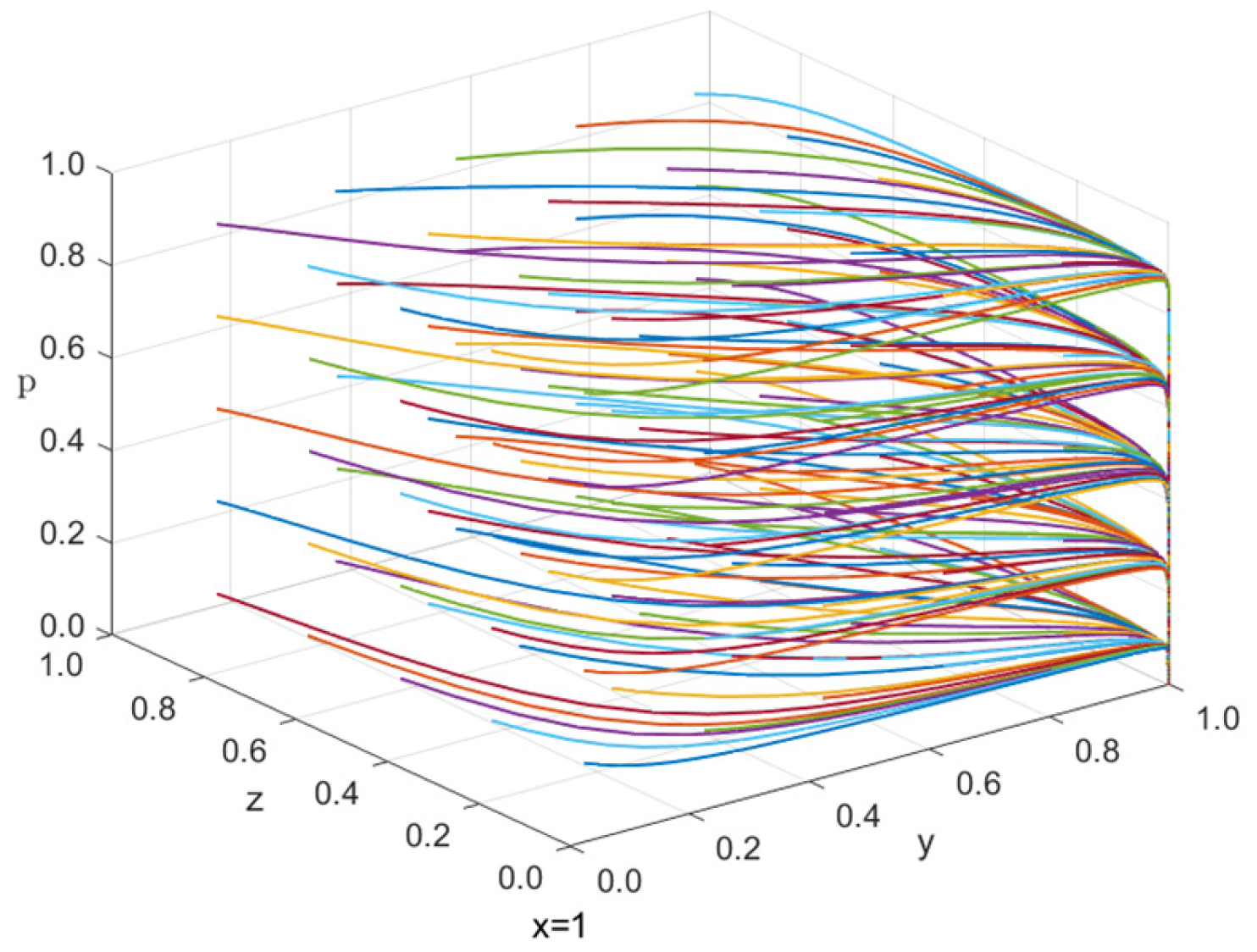

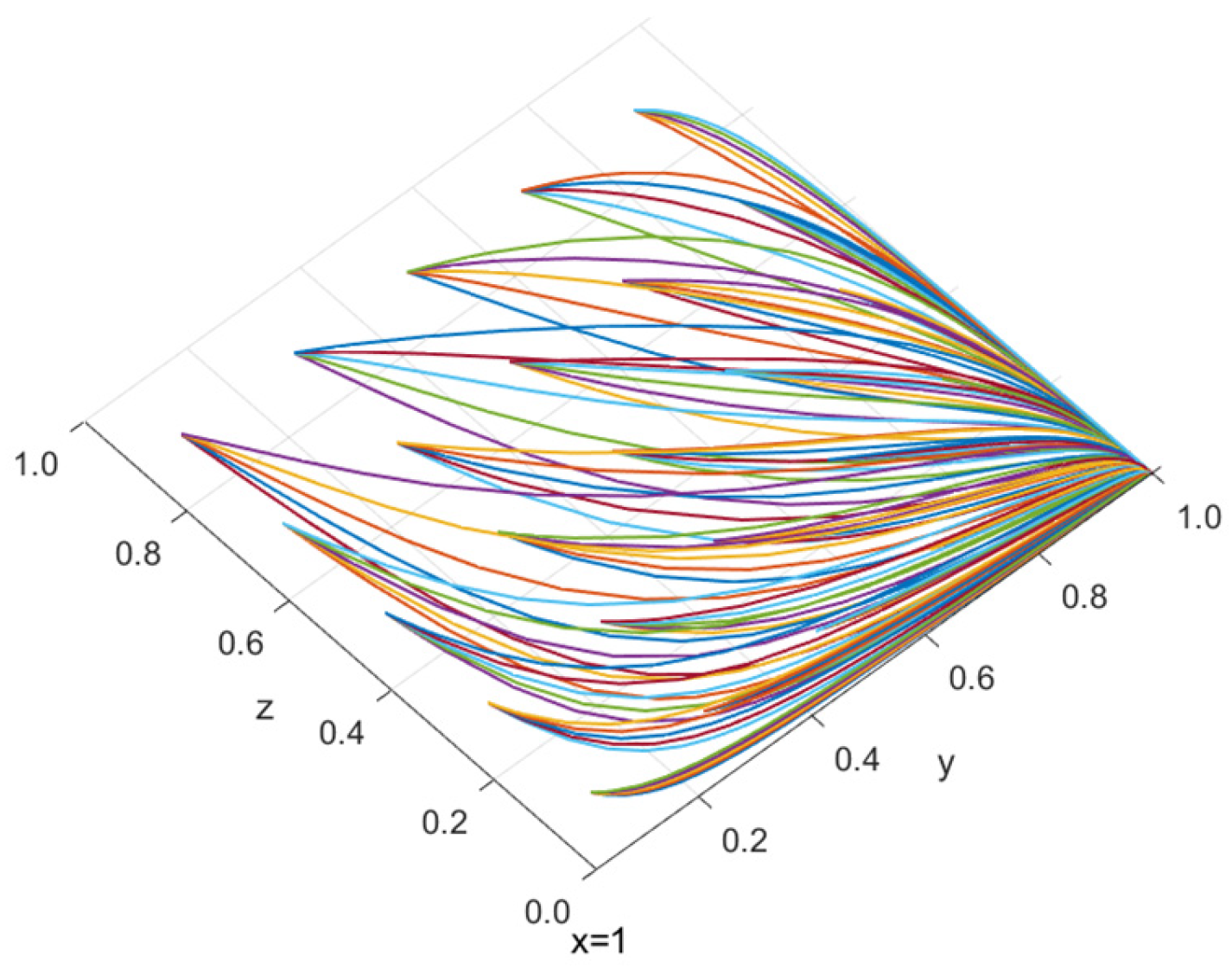

4.3. The Influence of x Initial Value on Evolutionary Equilibrium

4.4. The Influence of y Initial Value on Evolutionary Equilibrium

4.5. The Influence of z Initial Value on Evolutionary Equilibrium

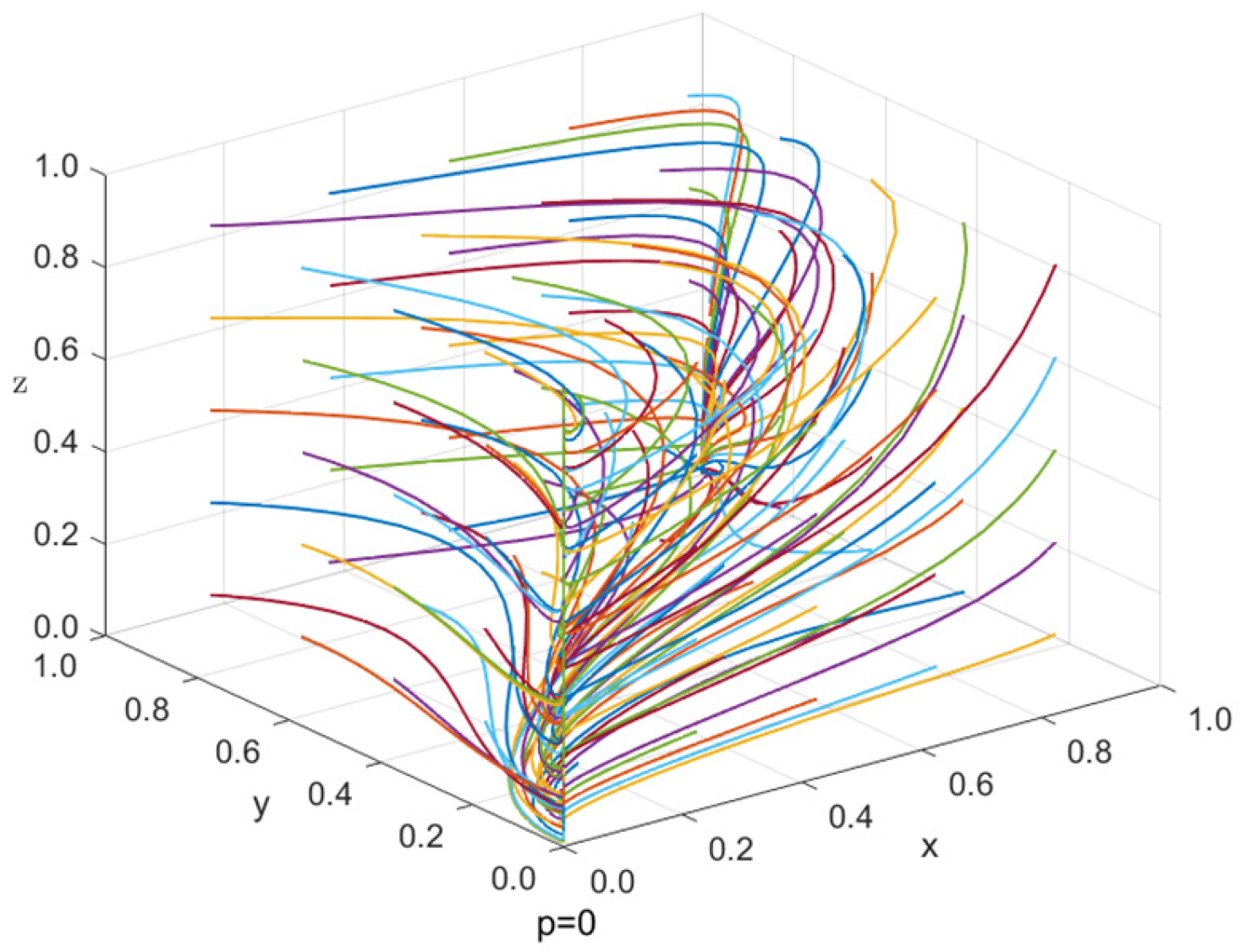

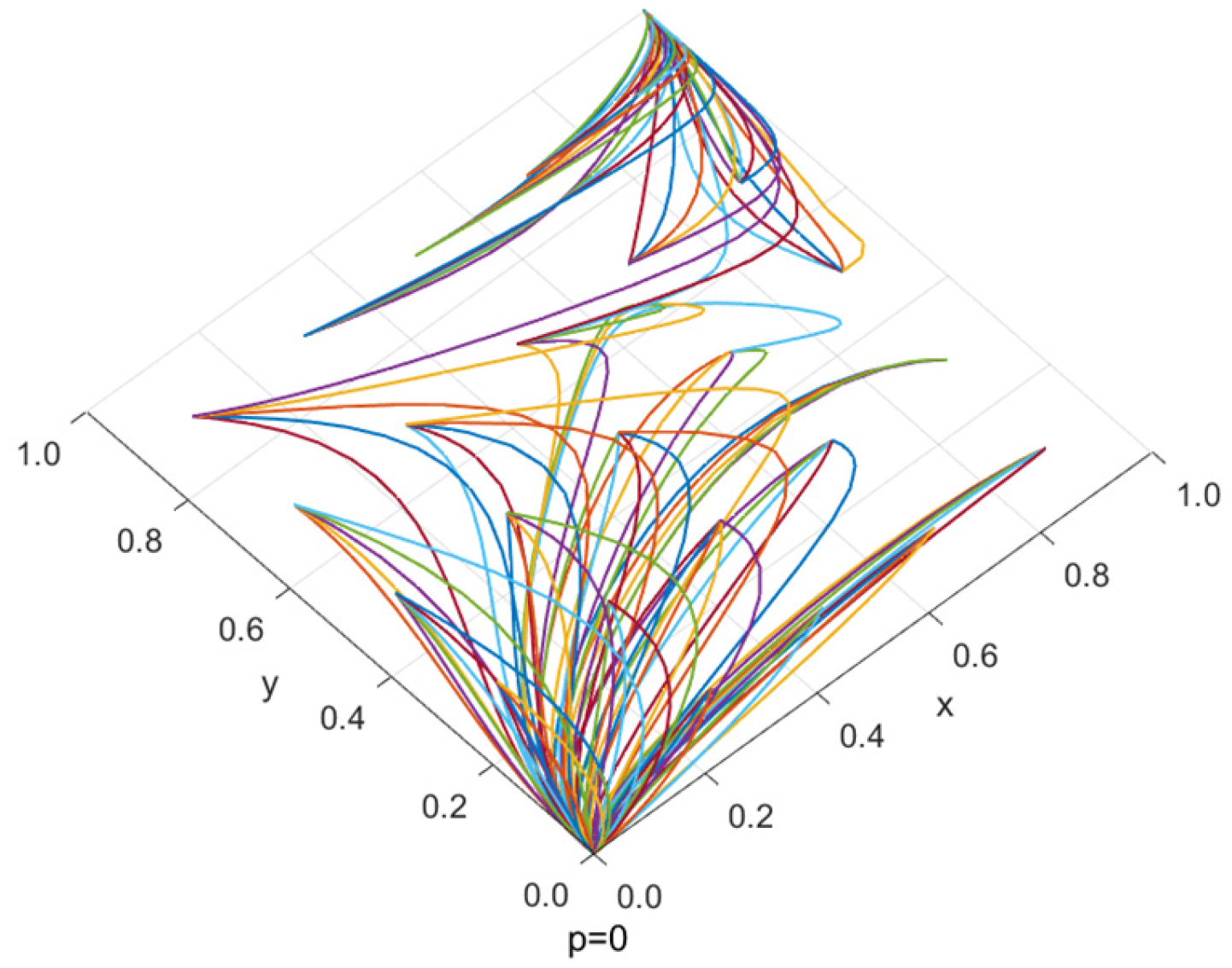

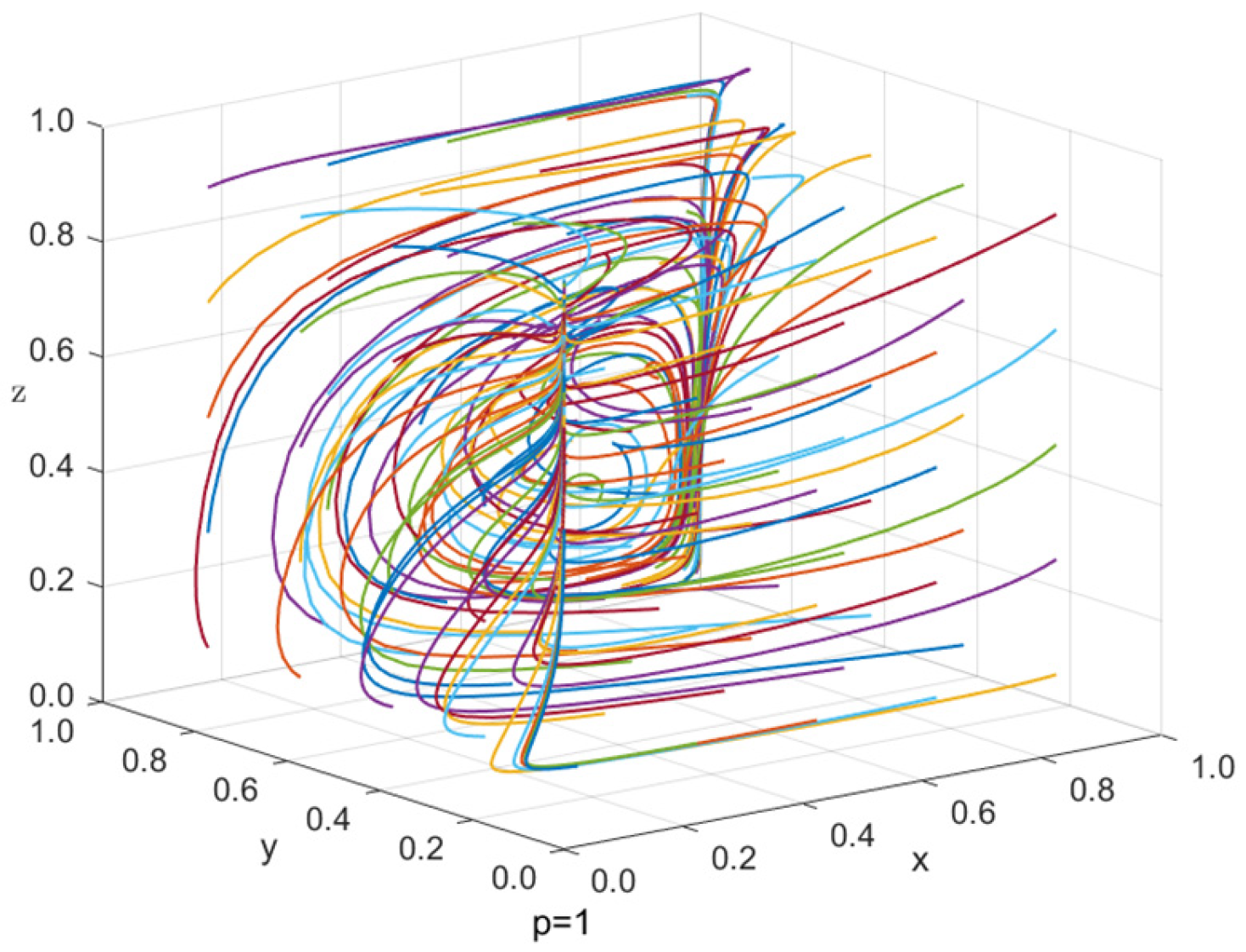

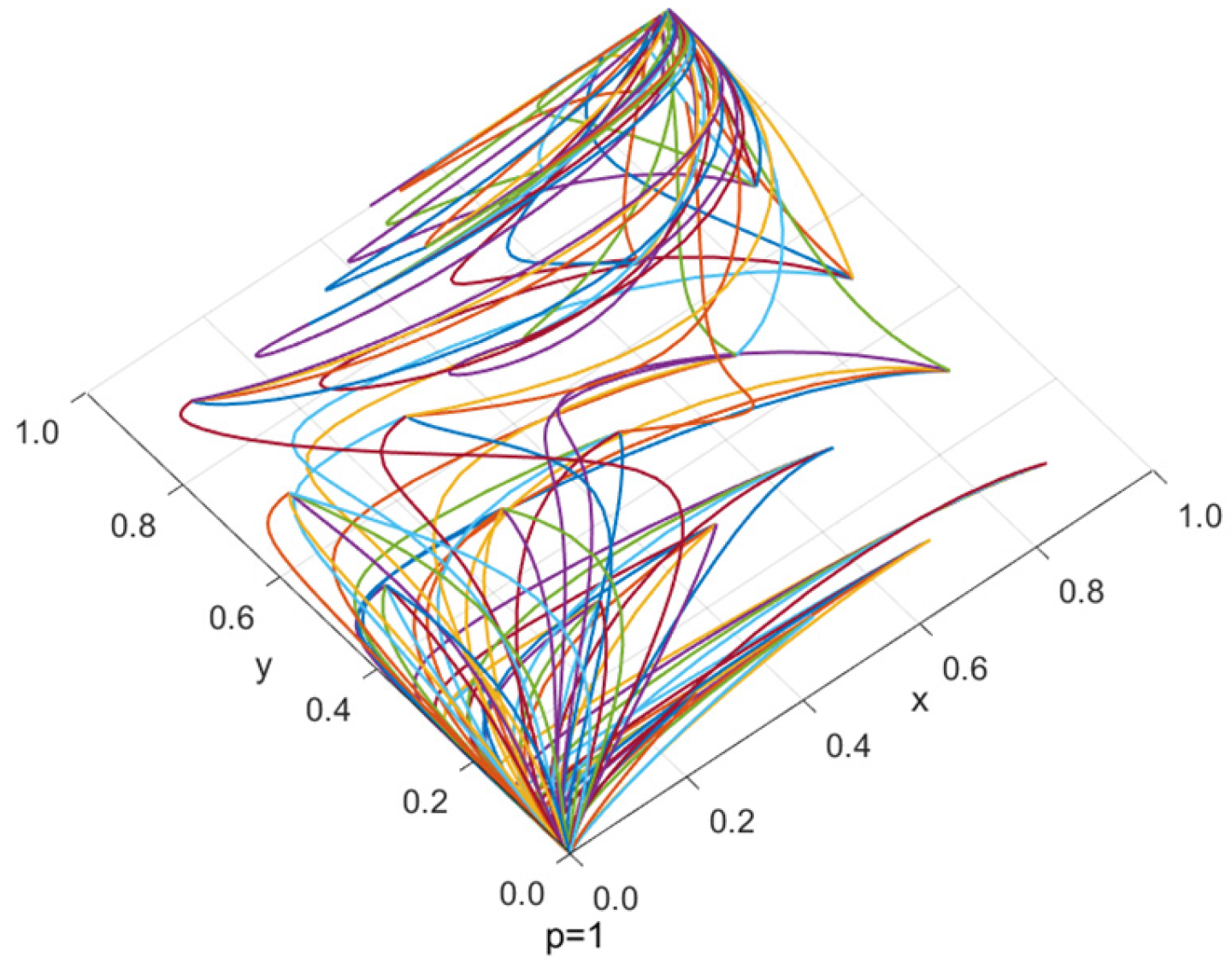

4.6. The Influence of p Initial Value on Evolutionary Equilibrium

5. Results and Management Enlightenment

5.1. Results

- (1)

- Public panic plays a two-way moderating role in the evolution of the behavior strategy of the government and enterprises. The level of public panic can indirectly affect the behavior strategies of the government and enterprises through public behavior and online public opinion; that is, the range of public panic corresponds to the strategy choices of the government and enterprises, as shown in Table A2.

- (2)

- The central government is more likely to influence the strategic choice of local governments than enterprises and netizens. When the central government chooses a strong supervision strategy, it will push local governments to fully disclose enterprise public opinion crisis event information. When the initial proportion of the central government’s strong supervision is larger, that is, the punishment imposed on local governments is greater, the local government will fully disclose the incident information because the punishment after being supervised will be greater than the impact of public panic.

- (3)

- The greater the proportion of enterprises adopting deceptive marketing strategies, the more likely the central government is to strengthen supervision, and the more inclined local governments are to fully disclose information related to the public opinion crisis of enterprises. To attract users’ attention, enhance brand value and maximize short-term revenue, enterprises will exaggerate or distort the original facts. This strategy not only expanded network traffic but also injected false information into public information flow, intensifying panic. As deceptive marketing spreads, public panic keeps accumulating, and the risk of collective boycotts increases. This forces the central government to adopt a strong supervision strategy to curb misleading propaganda and guide public sentiment, thereby reducing the risk of panic. When enterprises continuously adopt deceptive marketing strategies after public opinion events occur, the intensity of public panic depends on the completeness of information disclosure by local governments.

5.2. Management Enlightenment

- (1)

- User dimension: Local governments should carry out digital literacy and crisis information identification education for netizens to enhance their ability to discriminate between true and deceptive marketing information. Enterprises should help netizens quickly verify the facts of the crisis through transparent communication, traceable labels and interactive popular science, and strengthen their trust and participation in the brand’s sustainable commitment. This can not only promptly calm the panic during the peak period of public opinion, but also accumulate sustainable consumption preferences after the crisis, forming a long-term value network jointly maintained by enterprises and consumers.

- (2)

- Emotional dimension: Enterprises should upgrade their response to public opinion crises to the operation of sustainable emotional accounts. They should release verifiable information within the ESG framework at the first moment of a public opinion crisis and enhance emotional resonance with visual data, such as the progress of social welfare. First, conduct public relations with netizens through empathy statements. Second, invite consumers to participate in the co-creation of green solutions. Finally, share the sustainable achievements, transforming crisis panic into a deep recognition of the brand’s sustainable commitment, and thereby driving long-term green consumption and word-of-mouth expansion.

- (3)

- Content dimension: Enterprises can take the officially disclosed information after a crisis as content assets, transform the crisis information into sustainable and shareable stories and conduct authenticity marketing. Meanwhile, enterprises have launched remedial products, opened up consumer co-creation channels on social media and used UGC content to help optimize green products. Achieve a complete closed loop of emotional repair, brand co-creation, and repurchase locking, directly transforming public opinion crises into a sustainable growth flywheel.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

- (1)

- Empirical research verification: This study mainly relies on theoretical analysis and numerical simulation. Although it can reveal the evolution mechanism of panic emotions and the dynamic characteristics of public opinion dissemination, it lacks specific empirical data to verify the accuracy and validity of the model. In the future, the model can be empirically verified by combining specific cases and big data analysis to further improve the theoretical framework.

- (2)

- Extended research on influencing factors: This study mainly focuses on the bidirectional supervision effect of panic emotions, while the role of other emotions (such as optimism, anger, etc.) in the dissemination of public opinion has not been deeply analyzed. In the future, it is necessary to study the role of other emotions (such as optimism, anger, etc.) in public opinion dissemination and their impact on market behavior.

- (3)

- Practical application research: This study mainly explores the evolution mechanism of public panic and the dynamic characteristics of public opinion dissemination in enterprise public opinion crises from a macro-perspective, lacking targeted research for specific industries. In the future, the marketing strategies of different industries in response to public opinion crisis events should be analyzed, providing more comprehensive practical support for sustainable marketing.

6.2. Conclusions

- (1)

- Deepening the perspective on micro-subject analysis: We conducted an in-depth analysis of the behavioral factors of each participating agent in public opinion dissemination at the micro level, making up for the deficiency of existing research in the analysis of micro-agents. It provides new perspectives and entry points for subsequent research, promoting the development of public opinion dissemination research towards a more detailed and in-depth direction.

- (2)

- Constructing a multi-agent evolutionary game model: We constructed an evolutionary game model involving the central government, local government, enterprises and netizens, providing a new methodological tool for studying the interaction among the agents in the process of complex public opinion dissemination. This multi-agent analytical approach helps us to understand the dynamic characteristics of public opinion dissemination more comprehensively.

- (3)

- Performing simulation analysis and a simulation: Based on the four-party evolution game model of crisis public opinion, the behavioral trajectories and panic degree inflection points of the central government, local governments, enterprises and netizens under different strategy combinations are simulated to provide decision support for enterprises’ crisis response and sustainable marketing. The simulation results can be directly transformed into crisis communication scripts, information disclosure rhythms and green product launch strategies. This can not only quickly reduce public panic during the peak stage of public opinion dissemination but also accumulate brand trust and sustainable consumption assets after the crisis, demonstrating the enterprise’s own social responsibility while maintaining its long-term profits.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Equilibrium Point | Characteristic Value 1 | Characteristic Value 2 | Characteristic Value 3 | Characteristic Value 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0, 0, 0, 0) | ||||

| (0, 0, 0, 1) | ||||

| (0, 0, 1, 0) | ||||

| (0, 0, 1, 1) | ||||

| (0, 1, 0, 0) | ||||

| (0, 1, 0, 1) | ||||

| (0, 1, 1, 0) | ||||

| (0, 1, 1, 1) | ||||

| (1, 0, 0, 0) | ||||

| (1, 0, 0, 1) | ||||

| (1, 0, 1, 0) | ||||

| (1, 0, 1, 1) | ||||

| (1, 1, 0, 0) | ||||

| (1, 1, 0, 1) | ||||

| (1, 1, 1, 0) | ||||

| (1, 1, 1, 1) |

| Strategy | Central Government | Local Government | Enterprises | Netizen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0, 0, 0, 0) | (Weak supervision, partial disclosure, deceptive marketing, non-participate in dissemination) | The difference () between the degree of public panic under the strong supervision strategy and the weak supervision strategy is greater than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q1. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q1. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is less than the critical value V1. | / |

| (0, 0, 1, 0) | (Weak supervision, partial disclosure, authentic marketing, non-participate in dissemination) | The difference () between the degree of public panic under the strong supervision strategy and the weak supervision strategy is greater than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q1. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q1. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is greater than the critical value V1. | The difference () between the cost incurred by netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy and the social benefits obtained by enterprises when they truthfully disseminate information is greater than the opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true. |

| (0, 0, 1, 1) | (Weak supervision, partial disclosure, authentic marketing, participate in dissemination) | The difference () between the degree of public panic under the strong supervision strategy and the weak supervision strategy is greater than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q1. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q1. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is greater than the critical value V2. | The difference () between the cost incurred by netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy and the social benefits obtained by enterprises when they truthfully disseminate information is less than the opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true. |

| (0, 1, 0, 0) | (Weak supervision, full disclosure, deceptive marketing, non-participate in dissemination) | The difference () between the degree of public panic under the strong supervision strategy and the weak supervision strategy is greater than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q1. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q1. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is less than the critical value V1. | / |

| (0, 1, 1, 0) | (Weak supervision, full disclosure, authentic marketing, non-participate in dissemination) | The difference () between the degree of public panic under the strong supervision strategy and the weak supervision strategy is greater than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q1. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q1. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is greater than the critical value V1. | The difference () between the cost incurred by netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy and the social benefits obtained by enterprises when they truthfully disseminate information is less than the opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true. |

| (0, 1, 1, 1) | (Weak supervision, full disclosure, authentic marketing, participate in dissemination) | The difference () between the degree of public panic under the strong supervision strategy and the weak supervision strategy is greater than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q1. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q1. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is greater than the critical value V2. | The difference () between the cost incurred by netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy and the social benefits obtained by enterprises when they truthfully disseminate information is less than the opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true. |

| (1, 0, 0, 0) | (strong supervision, partial disclosure, deceptive marketing, non-participate in dissemination) | The difference () in public panic between strong supervision and weak supervision is less than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q2. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q2. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is less than the critical value V3. | / |

| (1, 0, 1, 0) | (strong supervision, partial disclosure, authentic marketing, non-participate in dissemination) | The difference () in public panic between strong supervision and weak supervision is less than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q2. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q2. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is greater than the critical value V3. | The difference () between the cost incurred by netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy and the social benefits obtained by enterprises when they truthfully disseminate information is greater than the opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true. |

| (1, 0, 1, 1) | (strong supervision, partial disclosure, authentic marketing, participate in dissemination) | The difference () in public panic between strong supervision and weak supervision is less than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q2. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q2. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is greater than the critical value V4. | The difference () between the cost incurred by netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy and the social benefits obtained by enterprises when they truthfully disseminate information is less than the opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true. |

| (1, 1, 0, 0) | (strong supervision, full disclosure, deceptive marketing, non-participate in dissemination) | The difference () in public panic between strong supervision and weak supervision is less than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q2. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q2. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is less than the critical value V3. | / |

| (1, 1, 1, 0) | (strong supervision, full disclosure, authentic marketing, non-participate in dissemination) | The difference () in public panic between strong supervision and weak supervision is less than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q2. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q2. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is greater than the critical value V3. | The difference () between the cost incurred by netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy and the social benefits obtained by enterprises when they truthfully disseminate information is greater than the opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true. |

| (1, 1, 1, 1) | (strong supervision, full disclosure, authentic marketing, participate in dissemination) | The difference () in public panic between strong supervision and weak supervision is less than the critical value P. | The proportion of public panic converted into the loss of social benefits for local governments is greater than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into the loss of economic benefits for enterprises, the difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is less than the critical value Q2. The proportion of public panic converted into social benefit losses for local governments is less than the product of the tax rate paid by enterprises and the proportion of public panic converted into economic benefit losses for enterprises. The difference () in public panic under the full disclosure and partial disclosure strategies of local governments is greater than the critical value Q2. | The difference () in the degree of public panic caused by authentic marketing and deceptive marketing strategies is greater than the critical value V4. | The difference () between the cost incurred by netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy and the social benefits obtained by enterprises when they truthfully disseminate information is less than the opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true. |

References

- Qu, Y.; Chen, H. Research on endogenous internet public opinion dissemination in Chinese universities based on SNIDR model. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 44, 9901–9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, C.; Dong, X. Risk prediction and credibility detection of network public opinion using blockchain technology. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 187, 122177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Zheng, H.; Qiao, G.; Geng, L.; Wang, K. Online public opinion dissemination model and simulation under media intervention from different perspectives. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 166, 112959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Kong, F. Research on online public opinion in the investigation of the “7–20” extra rainstorm and flooding disaster in Zhengzhou, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 105, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Q.; Ji, S.; Zhang, C. Public Opinion About COVID-19 on a Microblog Platform in China: Topic Modeling and Multidimensional Sentiment Analysis of Social Media. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e47508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; He, H.; Zhao, X.; Lin, J. Modeling and simulation of microblog-based public health emergency-associated public opinion communication. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Yang, S.; Wang, K.; Zhou, Q.; Geng, L. Modeling public opinion dissemination in a multilayer network with SEIR model based on real social networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 125, 106719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Song, Y. Multi-Subject Decision-Making Analysis in the Public Opinion of Emergencies: From an Evolutionary Game Perspective. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, H.; Huang, W. Cooperation behavior of opinion leaders and official media on the governance of negative public opinion in the context of the epidemic: An evolutionary game analysis in the perspective of prospect theory. Complexity 2023, 2023, 1366260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Su, Q.; Gong, Z.; Zeng, X. Fractional order time-delay multivariable discrete grey model for short-term online public opinion prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 197, 116691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengesi, S.; Oladunni, T.; Olusegun, R.; Audu, H. A machine learning-sentiment analysis on monkeypox outbreak: An extensive dataset to show the polarity of public opinion from Twitter tweets. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 11811–11826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Hansen, F.; Repke, T.; Baum, C.M.; Brutschin, E.; Callaghan, M.W.; Debnath, R.; Lamb, W.F.; Low, S.; Lück, S.; Roberts, C.; et al. Attention, sentiments and emotions towards emerging climate technologies on Twitter. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 83, 102765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, R.; Riaz, R.; Nasir, T.; Hussain, W. Public Opinion and Policy Development: A Psychological Approach to Understanding the Role of Public Sentiment in Shaping LegislationA Case Study of Law, Psychology, Media and Policy Development Nexus. Annu. Methodol. Arch. Res. Rev. 2025, 3, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Wang, Y.; Fan, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Gou, J. Discovering e-commerce user groups from online comments: An emotional correlation analysis-based clustering method. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 113, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Wu, P.; Yeo, C.K.; Li, G. Emotion-cognitive reasoning integrated BERT for sentiment analysis of online public opinions on emergencies. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, S. A deep learning-based sentiment analysis approach (MF-CNN-BILSTM) and topic modeling of tweets related to the Ukraine–Russia conflict. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 143, 110404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarantelli, E.L. The nature and conditions of panic. Am. J. Sociol. 1954, 60, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarantelli, E.L. The behavior of panic participants. Sociol. Soc. Res. 1957, 41, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, T.A.; Schochspana, M. Bioterrorism and the people: How to vaccinate a city against panic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman Ira, J.; Evdokas, A. Appraisals Cause Experienced Emotions: Experimental Evidence. Cogn. Emot. 2008, 18, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakariyahu, R.; Lawal, R.; Yusuf, A.; Olatunji, A. Mass shootings, investors’ panic, and market anomalies. Econ. Lett. 2023, 231, 111284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metrick, A. The failure of silicon valley bank and the panic of 2023. J. Econ. Perspect. 2024, 38, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, X.; Lu, P.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S. Spatio-temporal evolution of public opinion on urban flooding: Case study of the 7.20 Henan extreme flood event. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 100, 104175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iuliis, M.; Battegazzorre, E.; Domaneschi, M.; Cimellaro, G.P.; Bottino, A.G. Large scale simulation of pedestrian seismic evacuation including panic behavior. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 94, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L.; Ni, Y.; Liu, X. Government’s public panic emergency capacity assessment and response strategies under sudden epidemics: A fuzzy Petri net-based approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Long, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, C.; Xing, M.; Zhang, S. Experimental study on emergency psychophysiological and behavioral reactions to coal mining accidents. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2024, 49, 541–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Wei, B.; Han, C.; Jia, P.; Zhu, W.; Li, C.; Ma, Y. Improved Crowd Dynamics Analysis Considering Physical Contact Force and Panic Emotional Propagation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 26, 1840–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Huo, F.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, J. An evacuation model considering pedestrian crowding and stampede under terrorist attacks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 249, 110230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwell, M. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference; Little, Brown and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.C.; Nilchiani, R.R.; Ganguly, A.; Vierlboeck, M. Evaluating the tipping point of a complex system: The case of disruptive technology. Syst. Eng. 2024, 28, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay; Narayan, S.; Gupta, A.K. Predicting Jams in Heterogeneous Disordered Traffic: Insights from Tipping Point Theory. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 125, 116254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russill, C.; Lavin, C. Tipping point discourse in dangerous times. Can. Rev. Am. Stud. 2012, 42, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Variable Declaration | |

|---|---|---|

| Central government | C1 | The supervision cost of central government under the strong supervision strategy |

| C2 | The central government’s supervision cost of public opinion under the strong supervision strategy | |

| C3 | The supervision cost of central government to local government under the weak supervision strategy | |

| C4 | The supervision cost of the central government on public opinion under the weak supervision strategy | |

| S1 | Social gains from the central government’s strong supervision strategy | |

| S2 | Social gains from the central government’s weak supervision strategy | |

| a | The proportion of public fear translated into loss of social benefits for the central government | |

| d | The proportion of the degree of public panic transformed into the cost of public opinion supervision by the central government | |

| Local government | C5 | Costs incurred when local governments choose a full disclosure strategy |

| C6 | Costs incurred when local governments choose to disclose parts and report them | |

| C7 | Costs incurred when local governments choose to disclose parts and report them | |

| S3 | Social gains when local governments are fully open | |

| S4 | The social benefits of partial disclosure of local governments | |

| S5 | Some local governments disclose the social gains lost by the central government’s strong supervision when they fail to report | |

| S6 | Some local governments disclose the social gains lost by the central government’s weak supervision when they fail to report | |

| b | The proportion of public panic translated into loss of social benefits for local governments | |

| w | The probability of local governments choosing to report to the central government under the partial disclosure strategy | |

| Enterprises | C8 | The costs generated by the authentic marketing strategies of enterprises |

| C9 | The costs resulting from deceptive marketing strategies of enterprises | |

| E1 | The economic benefits obtained by the authentic marketing strategies of enterprises | |

| E2 | The economic benefits obtained by enterprises through deceptive marketing strategies | |

| E3 | The economic gains lost by enterprises under the strict supervision strategy of the central government due to deceptive marketing by enterprises | |

| E4 | The economic gains lost by enterprises under the weak supervision strategy of the central government due to deceptive marketing by enterprises | |

| A1 | The change in economic benefits of enterprises that conduct authentic marketing when netizens disseminate true information | |

| A2 | The change in economic benefits of enterprises that engage in deceptive marketing when netizens spread false information | |

| F | The reward money obtained by the enterprise through its authentic marketing strategy | |

| r | The tax rate at which enterprises pay taxes to local governments | |

| c | The proportion of public panic transformed into enterprises economic profit | |

| Netizens | C10 | The cost of netizens choosing to participate in the dissemination strategy |

| C11 | The opportunity cost paid by netizens when they choose not to participate in the dissemination but the information is true | |

| S7 | The social benefits obtained by netizens when they participate in the truthful dissemination of enterprises | |

| S8 | The social benefits obtained by netizens when they participate in spreading false dissemination of enterprises | |

| S9 | The diminished social reputation of netizens who spread deceptive marketing information from enterprises when under strong supervision by the central government | |

| S10 | The diminished social reputation of netizens who spread deceptive marketing information from enterprises when under weak supervision by the central government. | |

| H1 | Extra benefits for netizens when the central government tightens supervision | |

| H2 | Extra benefits for netizens t users when the central government is weak in supervision | |

| E5 | The economic losses incurred when netizens choose to participate in the dissemination but encounter false information | |

| K | The highest level of public panic after an emergency | |

| ni | Coefficient of public panic | |

| Strategy Combination | g1 | g2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e1 | e2 | e1 | e2 | ||

| l1 | f1 | ||||

| f2 | |||||

| l2 | f1 | ||||

| f2 | |||||

| Strategy Combination | Stable Condition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (g2, e2, l2, f2) | ||||||

| 2 | (g2, e2, l1, f2) | ||||||

| 3 | (g2, e2, l1, f1) | ||||||

| 4 | (g2, e1, l2, f2) | ||||||

| 5 | (g2, e1, l1, f2) | ||||||

| 6 | (g2, e1, l1, f1) | ||||||

| 7 | (g1, e2, l2, f2) | ||||||

| 8 | (g1, e2, l1, f2) | ||||||

| 9 | (g1, e2, l1, f1) | ||||||

| 10 | (g1, e1, l2, f2) | ||||||

| 11 | (g1, e1, l1, f2) | ||||||

| 12 | (g1, e1, l1, f1) | ||||||

| Variable | Value | Variable | Value | Variable | Value | Variable | Value | Variable | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 100 | S1 | 250 | A2 | 4 | w | 0.4 | n11 | 0.7 |

| C2 | 80 | S2 | 80 | E1 | 120 | n1 | 0.15 | n12 | 0.45 |

| C3 | 40 | S3 | 150 | E2 | 200 | n2 | 0.1 | n13 | 0.45 |

| C4 | 20 | S4 | 40 | E3 | 150 | n3 | 0.6 | n14 | 0.4 |

| C5 | 60 | S5 | 100 | E4 | 60 | n4 | 0.35 | n15 | 0.9 |

| C6 | 40 | S6 | 50 | E5 | 80 | n5 | 0.3 | n16 | 0.65 |

| C7 | 30 | S7 | 15 | F | 40 | n6 | 0.25 | r | 0.25 |

| C8 | 20 | S8 | 10 | a | 0.1 | n7 | 0.75 | K | 1000 |

| C9 | 50 | S9 | 20 | b | 0.15 | n8 | 0.5 | H1 | 30 |

| C10 | 5 | S10 | 8 | c | 0.3 | n9 | 0.25 | H2 | 10 |

| C11 | 3 | A1 | 12 | d | 0.2 | n10 | 0.2 |

| Frontage Value | Value | Frontage Value | Value | Frontage Value | Value | Frontage Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 0.167 | Q2 | 1.92 | V2 | −0.23 | V4 | −0.59 |

| Q1 | 1.52 | V1 | −0.2 | V3 | −0.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, X.; Shang, J.; Yang, Y. Research on Enterprise Public Opinion Crisis Response Strategies in the Context of Information Asymmetry. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17101694

You X, Shang J, Yang Y. Research on Enterprise Public Opinion Crisis Response Strategies in the Context of Information Asymmetry. Symmetry. 2025; 17(10):1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17101694

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Xinshang, Jieyao Shang, and Yanbo Yang. 2025. "Research on Enterprise Public Opinion Crisis Response Strategies in the Context of Information Asymmetry" Symmetry 17, no. 10: 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17101694

APA StyleYou, X., Shang, J., & Yang, Y. (2025). Research on Enterprise Public Opinion Crisis Response Strategies in the Context of Information Asymmetry. Symmetry, 17(10), 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17101694