4. Maximum Coverage by k Parallel Lines

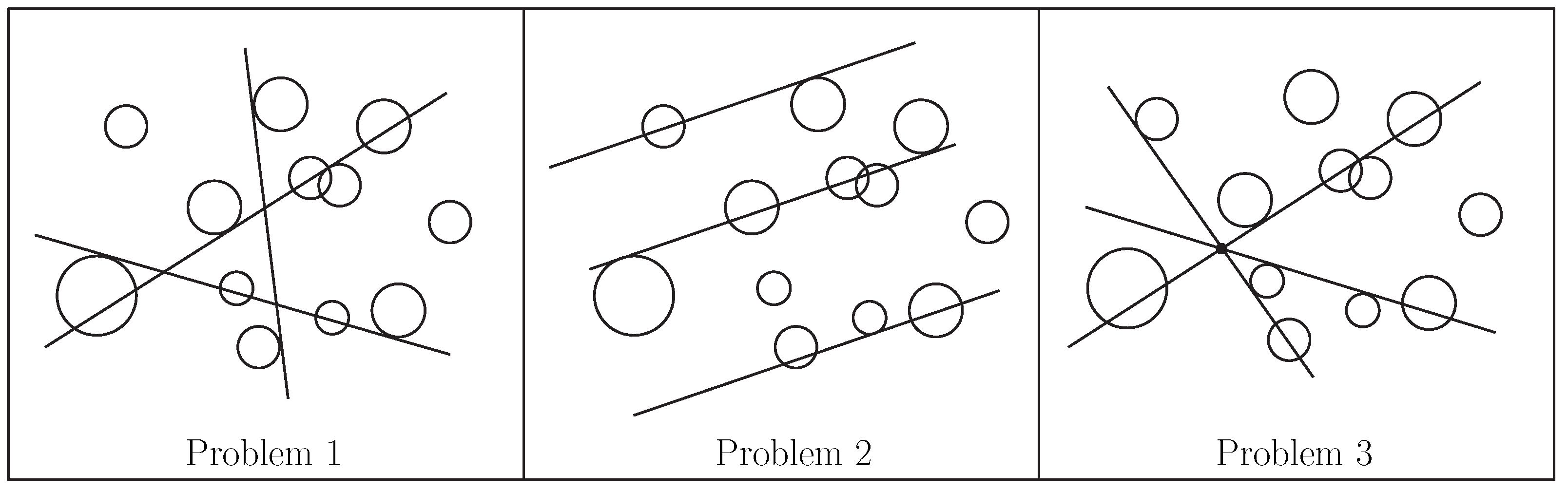

Given a set of n disks in the plane and an integer , we would like to find k parallel lines that together intersect the maximum number of disks in . We first show that this problem can be solved by reducing it to the partial interval hitting set problem. Then, we show how to improve the running time for small k.

We begin with an observation about optimal sets of k parallel lines. Given an optimal set of k parallel lines, it is always possible to translate a line of this optimal solution so that the line becomes tangent to an input disk, while keeping the same set of intersected disks. Therefore, we may assume that each line is tangent to a disk , for .

For each , we may assume that there exists a common tangent between and some other disk in . Otherwise, for each , we must have or . Therefore, without loss of generality, the disks form a chain of inclusion . In addition, all the other disks are either contained in or contain . No disk in can be contained in , as otherwise we could improve the solution by translating until it crosses this disk. It follows that , contradicting our assumption that .

We then rotate tangentially around simultaneously for all until one of the k lines becomes tangent to another disk or ceases to be tangent to it. Let denote the k lines after the rotation. As the set of disks intersected by contains the set of disks intersected by for all , we can replace our optimal set of parallel lines with . Thus we have the following observation.

Observation 1. There exists an optimal set of k parallel lines such that every line is tangent to an input disk and at least one of them is a common tangent of .

Once we know the direction of an optimal set of lines, we project the disks in

onto a line orthogonal to this direction. We obtain

n closed intervals on this line. The problem of finding

k lines with this orientation that intersect the maximum number of disks is equivalent to the problem of finding

k points that together intersect the maximum number of intervals, which is the

problem. In

Section 6, Lemma 6, we show that it can be solved in

time using

space.

By Observation 1, we have possible orientations. So we can solve the maximum intersection problem by k parallel lines in time as k is a constant. When , we give two different algorithms which improve the running time and we provide a space-time trade-off.

Improvements for

Let and be two disks in . Let and be two parallel lines such that is tangent to for . For , we maintain an array of Booleans that records for each disk in whether it is intersected by , and we keep a counter for the number of disks in which are intersected by or . Now we simultaneously rotate the two lines tangentially around and , respectively.

Whenever becomes tangent to a disk other than , an element of the boolean list for needs to be updated and the number of intersected disks may change. The same holds for and . We call this an event. As any two disks have at most 4 common tangents, there are events in total. We precompute them, and sort them according to the orientation of the common tangents that they correspond to in time.

For each event, the number of disks in intersected by or increases or decreases by at most one, and we can update the boolean lists and compute the number of intersected disks in time. There are events in total, so it takes time.

We repeat this for every pair of disks in and find an event where the number of intersected disks is maximized. By Observation 1, the two parallel lines and corresponding to this event is an optimal solution. Thus, we obtain the following result.

Lemma 4. Given a set of n disks in the plane, we can find two parallel lines that together intersect the maximum number of disks in in time using space.

We can improve the running time to time using space as follows.

Let . Partition the disks into disjoint groups, each consisting of T disks, except possibly the last group containing less than T disks. Let be the set of groups.

For every subset of of size at most two,

- (a)

Let . For each disk , compute the sorted list of the other disks in intersected by the tangent line rotating around D in time. It takes time for all disks in .

- (b)

For a fixed pair , we can find the maximum number of disks intersected by , in time as the ordering of the events has been precomputed. So over all the pairs , it takes time to find optimal lines , .

We consider subsets of , and we spend time for each subset. Thus we spend time in total, which is time.

Theorem 3. Given a set of n disks in the plane and a positive integer k, we can find k parallel lines that together intersect the maximum number of disks in in time using space. For , we can find such two parallel lines in time using space and in time using space.

5. Maximum Coverage by k Lines through a Point

Concurrent lines are lines that meet at a common point, called their concurrency point. Given a set of n disks in the plane and a positive integer k, we want to find k concurrent lines that together intersect the maximum number of disks in . We can solve this problem in time by Theorem 1 for .

For

, a simple modification of the algorithm from Theorem 2 gives a solution in

time. The idea is the following. We use the plane-sweep algorithm by Asano and Imai to compute the depth of our set of rectangles [

18]. We need to rule out the solutions consisting of two parallel lines, which correspond to points along the diagonal

in our arrangement of rectangles. So at each event

of the sweep, we add a negative weight

to the point

, which guarantees that it will not be returned as an optimal solution.

Therefore, we consider the case where , and we make the assumption that no two intersecting lines together intersect all the disks in , as otherwise we can simply solve the problem using our algorithm for .

Lemma 5. Suppose that no two intersecting lines together intersect all the disks in . Then there exists an optimal set of k lines for such that every line is tangent to an input disk and at least two of them are common tangents of .

Proof. Let be an optimal solution to our problem. Let be their concurrency point. When we rotate a line about , as does not intersect all the disks in , it must at some point become tangent to a disk in . So we rotate each line clockwise until it first becomes tangent to some disk in , obtaining a line . Then is still an optimal solution, and each line is tangent to a disk .

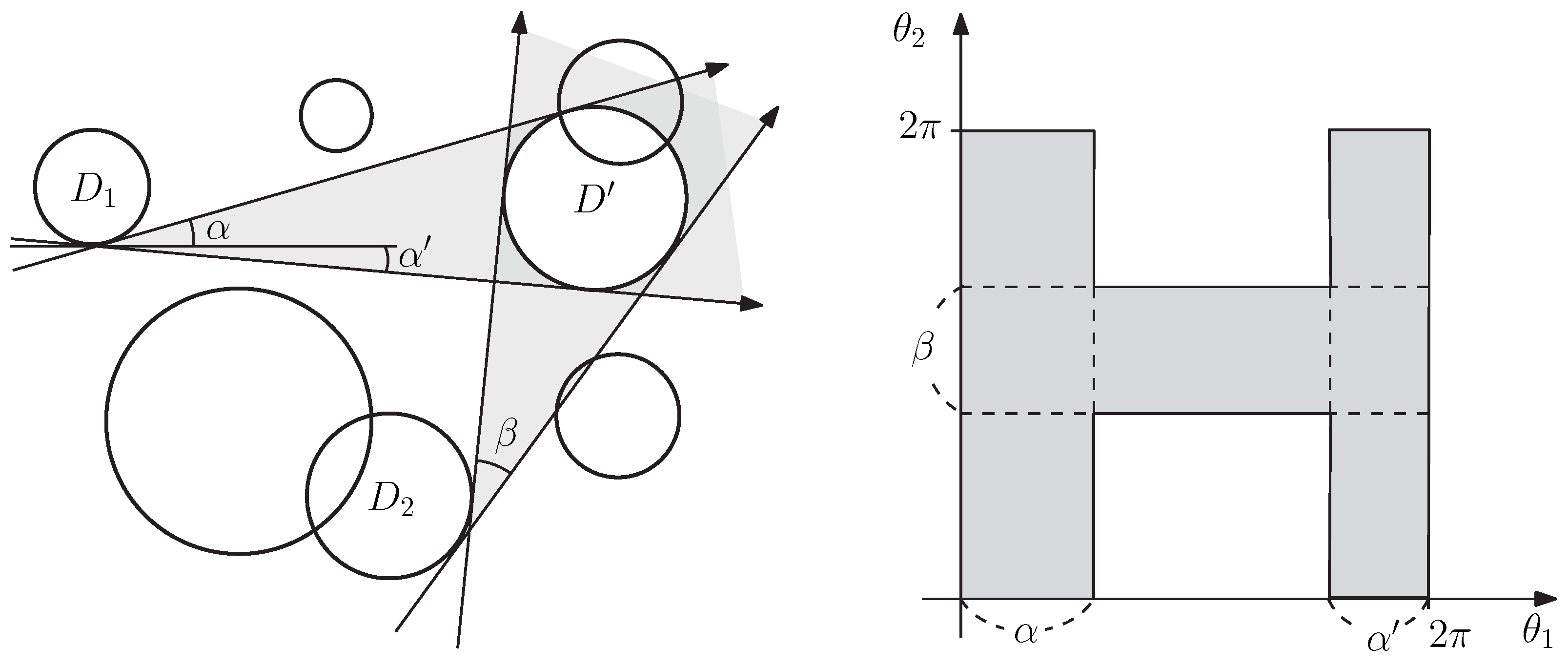

We move the intersection point along , while rotating each , tangentially around . By our assumption, no line parallel to intersects all the disks in . So must become tangent to some disk in at some point for every . Let be the point corresponding to the first such event, when p moves in either direction along . Then we obtain a new optimal solution such that is a common tangent of for some j with . If is a common tangent of , we are done. Otherwise, we apply the same argument as above to , obtaining a second common tangent. □

By Lemma 5, there exists an optimal set of k lines whose concurrency point is the intersection of two common tangents of . For every pair of common tangents , we consider the point of intersection as a candidate for being the concurrency point of an optimal solution. Thus we have candidates for being the concurrency point of an optimal solution.

Once we pick a concurrency candidate p, we can reduce our problem to the partial interval hitting set problem. Let ℓ and be the two common tangents that intersect at p. Without loss of generality, we assume that ℓ is parallel to the x-axis. Let be the set of disks in which are intersected by neither ℓ nor . For every disk D in , let be the interval of angles such that the line through p with orientation intersects D. Note that is a closed interval in . Now we solve for these intervals for , and . Let denote an optimal solution for the problem. Let denote the set of lines of orientation passing through p. Since is a set of lines that pass through p and that together intersect the maximum number of disks in , is an optimal set of k lines if ℓ and are contained in an optimal solution. Therefore, we can compute an optimal set of k concurrent lines by repeating this process for every concurrency candidate.

For

, we solve

for

, so we need to find a point that hits the maximum number of intervals, which can be done in

time by a simple scan after sorting the endpoints of the intervals. For

, Chrobak et al. ([

4] Section 3.1) show that

can be solved in

time, and we show that it can be done using only

space in

Section 6. Thus we can solve this problem in

time and

space for

, and in

time and

space for

.

We now show how the running time can be reduced to

for

, using

space. Our approach is based on a result presented in

Section 6 that shows how to update a solution to

for a set of intervals with moving endpoints where an event occurs when two endpoints collide or separate. We show in Lemma 7 that the solution can be updated in

time per event.

Let ℓ denote a common tangent of , and assume without loss of generality that ℓ is parallel to the x-axis. We show that we can find two lines and such that their intersection point lies on ℓ, and the number of disks in intersected by is maximized, in time. As the set of disks intersected by ℓ does not change for a fixed line ℓ, we do not take this set of disks into consideration.

Let denote the set of disks in that do not intersect ℓ. For a point p on ℓ, let be the collection of intervals which are defined for around p in the same manner as we explained in the reduction step above. We solve for and , and let be the solution. Let and denote the two lines through p with orientations and , respectively. These two lines together intersect the maximum number of disks in while passing through p.

Now suppose that we move p along ℓ. The endpoints of the intervals in will move along the real line. A solution to changes only if an event occurs, as otherwise the ordering of endpoints of the interval remains the same. The key point is that an event occurs only if p is on a concurrency candidate for ℓ. The reason is that, for a point , there exists two intervals in such that two endpoints from distinct intervals lie on the same point if and only if there exists a line which passes through q and is tangent to two disks in .

There are

concurrency candidates along

ℓ in total, and they can be precomputed and sorted along

ℓ in

time. From the pairs of disks which determine each concurrency candidate on

ℓ, the corresponding event can also be found directly. We handle all the events in order and store the best two lines,

and

, which together intersect the maximum number of disks in

. In

Section 6, Lemma 7, we show how to handle each event in

time. Thus, we can find

and

in

time in total.

We repeat this for every common tangent of . By Lemma 5, there always exists an optimal set of k lines such that one of the lines is a common tangent to two disks in . Thus, the best set of k lines found during the repetition is an optimal solution. Hence, we have just proved the following theorem.

Theorem 4. Given a set of n disks in the plane and a positive integer k, we can find k lines that pass through a common point and that together intersect the maximum number of disks in time using space. When , we can solve this problem in time using space, and time using space.

6. On the Partial Interval Hitting Set Problem

As we mentioned above, given

n closed intervals

,

on the real line, and a positive integer

, the partial hitting set problem is to find a set

H of

points on the real line that together hit the maximum number of intervals. We say that a point

q hits an interval

I if

[

2]. It is easy to see that, after shifting the solution points to the right until they each meet a right endpoint, that we may assume that the points in the solution are the right endpoints of

input intervals.

Chrobak et al. ([

4] Section 3.1) gave a dynamic-programming algorithm for this problem that runs in

time. We give a sketch of their algorithm. First, it sorts the intervals using their right endpoints and relabels them so that

. Let

be the maximum number of input intervals that can be hit by a subset

such that

and

, where

and

. Let

be the number of intervals

such that

, namely the intervals that are hit by

but not by

. We first set

to the number of intervals that contain

. Similarly, we set

to the number of intervals that contain

. Then, for every

and for every

, we can compute

using the recurrence relation

.

The output value is . Chrobak et al. use space as their algorithm precomputes all values in time . We show how the space usage can be reduced to without increasing the time bound.

Lemma 6. Given n closed intervals on the real line, and a positive integer γ, we can find a set of γ points on the line that together hit the maximum number of intervals in time using space.

Proof. We first compute the sorted list of the interval endpoints in increasing order. We let be the number of intervals that contain for . These values can be computed in time. For a fixed b with , can be computed for all in time once and are computed for all and all .

We show that for all can be computed in (amortized) time once is computed for all . For any fixed b with , let be the number of intervals such that , and let be the number of intervals such that . Let be the number of intervals such that . For any integers with , . Thus, and for all must be computed in advance when we compute from for all . By scanning the sorted list of interval endpoints, we can compute in time and for all in time. So we can compute for all in time. Additionally, we set .

For every , we compute for all and then compute for all h. It takes time for every . As and , it takes time in total using space. □

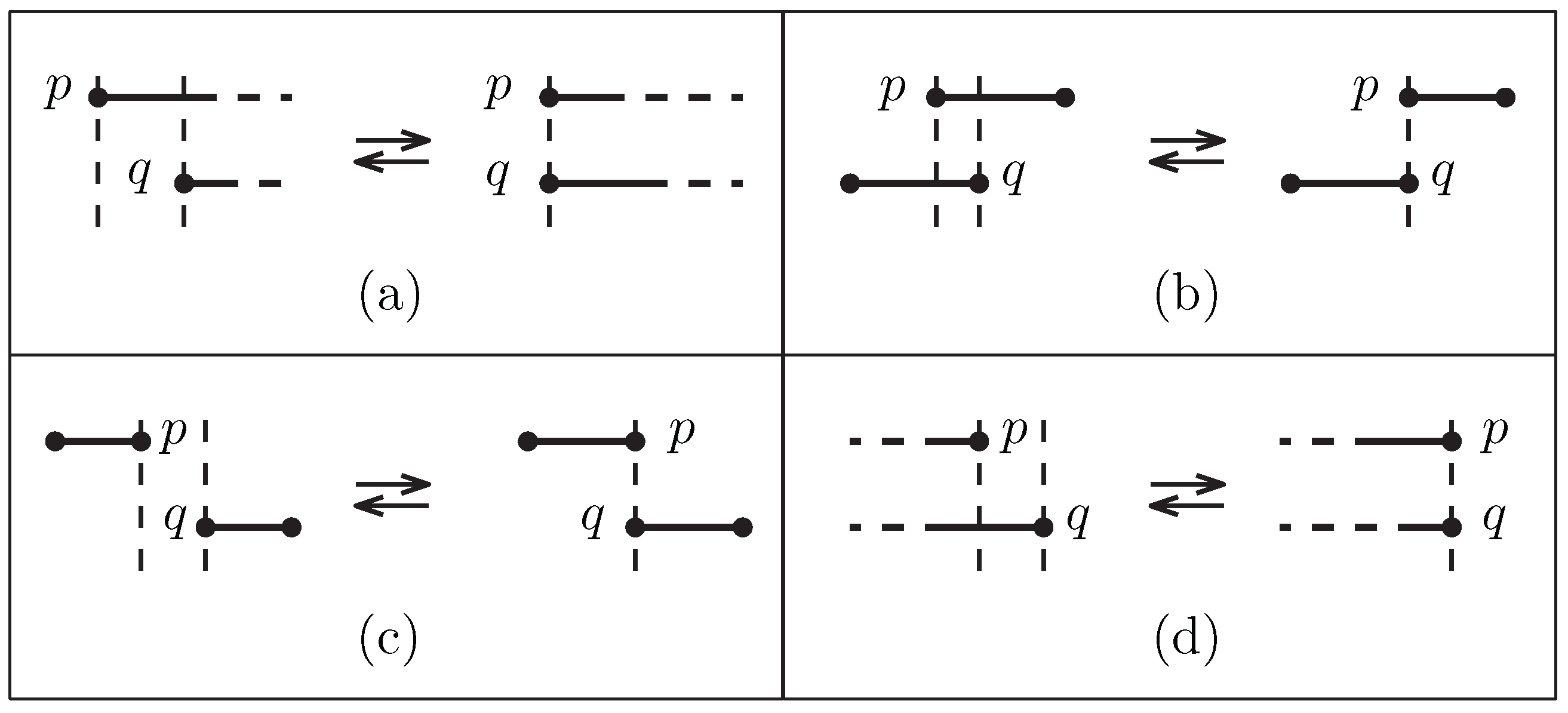

We now consider the case where the interval endpoints move along the real line, so each endpoint p is given as a function of the time . For two intervals and , let p and q denote two endpoints such that and . Let . If , that is, if for any that is close enough to we have , and then , we say that p and qcollide. On the other hand, if and , that is, if for any that is close enough to we have , then we say that p and q separate. We say that an event occurs when two endpoints collide or separate. An event at time is one of the following types:

- ()

Two points

p and

q, which are both left endpoints of intervals, collide or separate. (See

Figure 3a).

- ()

Two points

p and

q, where

p is the left endpoint of an interval and

q is the right endpoint of another interval, satisfy

and collide at

, or

p and

q separate at

and

. (See

Figure 3b).

- ()

Two points

p and

q, where

p is the right endpoint of an interval and

q is the left endpoint of another interval, satisfy

and collide at

, or

p and

q separate at

and

. (See

Figure 3c).

- ()

Two points

p and

q, which are both right endpoints of intervals, collide or separate. (See

Figure 3d).

Lemma 7. At each event, we can update an optimal solution to for in time after -time preprocessing using space.

Proof. Let denote the table which stores all , and let denote the table which stores all . For , we show that an event where two interval endpoints p and q collide or separate can be handled in time so that all elements of and store correct values reflecting the situation right after the event. We first assume that no three intervals endpoints coincide at any time. At the end of this proof, we explain how to handle these degenerate cases.

For an event of type , the set of intervals which are hit by a right endpoint does not change at all. Thus nothing in and needs to change.

For an event of type , let and be the two intervals involved in the event such that and . Then at this event, the set of intervals that are hit by will change, and the set of intervals hit by any other point does not change. The number of intervals hit by increases by 1 for the case where p and q collide, and this number decreases by 1 for the other case where p and q separate. It follows that among all for , is the only element which changes. The update of can be done in time. Among all for , however, more than one element can change. We show that we can compute the changes in time in total. For both cases where the points collide or separate, changes only if or in the following way. The value increases or decreases by 1 for all . The value increases or decreases by 1 if for . Thus we can update in time in total.

The observation that changes only if or implies that changes only if becomes larger than its original value for . This can be checked in time for every once and were computed. Using additional time, we update using the recurrence relation. Thus we can update in time in total. Then we can report a new solution by computing .

For an event of type , let and be the two intervals involved in the event such that , , and holds right after the event if p and q separate at this event. If , which happens only for the case where p and q separate, we just switch the labels of two intervals so that holds. Then is the only interval such that the set of intervals which are hit by its right endpoint changes by this event. The size of the set increases by 1 for the case where p and q collide, and the size of the set decreases by 1 for the case where p and q separate. It follows that among all for , is the only element which changes. The update of can be done in time. Among all for , however, more than one element can change. We show that we can compute the changes in time in total. For both cases where points collide or separate, changes only if . More precisely, the value increases or decreases by 1 if . Thus we can update in time in total.

The observation that is the only element which changes among all for implies that changes only if becomes larger than its original value for . This can be checked in time for every once and were computed. Using additional time, we update using the recurrence relation. Thus we can update in time in total. Then we can report a new solution by computing .

We now explain how to handle degenerate cases where more than 2 endpoints collide or separate at the same time t. So we have several events of the type LL, LR, RL or RR occurring at time t. In this case, we first separately handle in an arbitrary order each of the events where two points collide, in the way that is described above. Then we obtain the solution at time t with maximum coverage. After this, we handle in an arbitrary order all the events where two points separate at time t. □

7. Discussion and Conclusions

We addressed the problem of finding k lines that together intersect the maximum number of input disks. We considered two other variants, where the k output lines should be parallel, and where the k lines should pass through a common point. We presented the first algorithms for these problems.

For , the three problems coincide, and we give an time algorithm by applying a geometric dualization. As this problem is 3SUM-hard even for covering points, an -time algorithm for any is currently out of reach.

For the problem of finding lines that together intersect the maximum number of input disks, we first show that there exists an optimal set of k lines, each of which is tangent to two input disks. Using this observation, we show that the problem can be reduced to the problem of computing the depth of a set of boxes. The running time of our algorithm is when and is time when .

For the problem of finding k parallel lines that together intersect the maximum number of input disks for , it can be reduced to the Partial Interval Hitting Set problem once the direction of the output lines is fixed. We first give -time algorithm by observing that there exists an optimal set of k parallel lines such that every line is tangent to an input disk and at least one of them is tangent to two input disks in . Then we reduce the time complexity when , at the expense of increasing the space usage by a logarithmic factor.

Our results are the first nontrivial results of these three problems, which are maximum coverage problems in geometric settings. One natural question is to extend our results to other geometric settings, for instance to covering balls by lines in . Another possible direction for further work is to consider approximation algorithms. The maximum coverage problem for arbitrary sets is known to be NP-hard, and the straightforward greedy algorithm gives a -approximation of the optimum. Can we find better approximation algorithms in geometric settings?