Abstract

Let P be a set of points in general position in the plane. The edge disjointness graph of P is the graph whose vertices are the closed straight line segments with endpoints in P, two of which are adjacent in if and only if they are disjoint. In this paper we show that the connectivity of is at most , and that this upper bound is asymptotically tight. The proof is based on the analysis of the connectivity of , where denotes an n-point set that is almost 3-symmetric.

1. Introduction

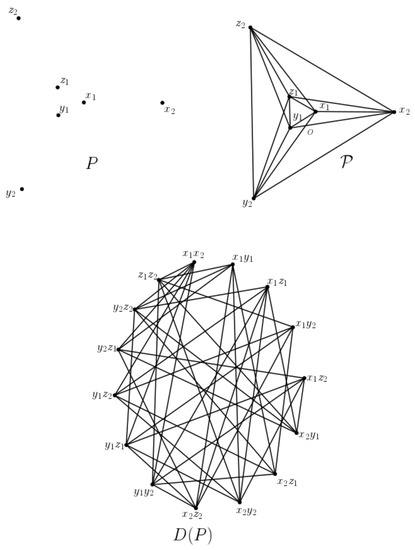

We call set in general position to any finite set of points in the Euclidean plane that does not contain three collinear elements. Let P be a set of points in general position. A segment of P is a closed straight line segment with its two endpoints being elements of P. In this paper, we shall use to denote the set of all segments of P. The edge disjointness graph of P is the graph whose vertex set is , and two elements of are adjacent in if and only if they are disjoint. We note that naturally defines a rectilinear drawing in the plane of the complete graph on n vertices. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The point set on the upper left is a set in general position. In the upper right we have , which can be seen as the rectilinear drawing of induced by P. As the largest number of crossings on any segment of is 1, then . The graph on the bottom part is the edge disjointness graph corresponding to P.

The class of edge disjointness graphs was introduced in 2005 by Araujo, Dumitrescu, Hurtado, Noy, and Urrutia [1], as a geometric version of the Kneser graphs. We recall that for with , the Kneser graph is defined as the graph whose vertices are all the k–subsets of and in which two k-subsets from an edge if and only if they are disjoint. In 1956, Kneser conjectured [2] that the chromatic number of is equal to . This conjecture was proved by Lovász [3] and (independently) by Bárány [4] in 1978. For more results on Kneser graphs, we refer the reader to [5,6,7,8,9,10] and the references therein.

In [1] the effort was focussed on the estimation of the chromatic number of , and a general lower bound was established. The problem of determining the exact value of remains open in general. On the other hand, there are only two families of point sets for which the exact value of is known: when P is in convex position [11,12], and when P is the double chain [13]. The connectivity of was studied by Leaños, Ndjatchi, and Ríos-Castro in [14], where it was shown that . We remark that in this paper we give a complementary upper bound for .

Recently, Aichholzer, Kynčl, Scheucher, and Vogtenhuber [15] have established an asymptotic upper bound for the maximum size of certain independent sets of vertices of . In 2017 Pach, Tardos, and Tóth [16] studied the chromatic number and the clique number of in the more general setting of for , i.e., when P is a subset of . More precisely, in [16] was shown that the chromatic number of is bounded by above by a polynomial function that depends on its clique number , and that the problem of determining any of or is NP-hard. Two years later, Pach and Tomon [17] have shown that if G is the disjointness graph of a set of grounded x-monotone curves in and , then .

Another wide research area, which is closely related to this work, is the study of the combinatorial properties of geometric graphs. We recall that a geometric graph is a graph whose vertex set V is a finite set of points in general positions in the plane, and the edges are straight line segments connecting some pairs of V. Clearly, the sets of segments studied in this paper correspond to a class of the geometric graph, namely the class of complete geometric graphs. See [18] for an excellent survey on geometric graphs.

Following [14], if and , then will be the element of with endpoints x and y. Let and be two distinct elements of , and suppose that . Then consists precisely of one point , because P is a set in general position. If o is an interior point of both and , then we say that they cross at o, and we will refer to o as a crossing of . See Figure 1 (upper right).

Let be a (non-empty) simple connected graph. As usual, if , then the distance between u and v in H will be denoted by , and we write to mean that u and v are adjacent in H. We note that the notation is similar to that used to denote the straight line segment defined by the points . However, none of these notations should be a source of confusion, because the former objects are vertices of a graph, and the latter are points in the plane.

The neighborhood of v in H is the set and is denoted by . If , then . The degree of v is the number . The number is the minimum degree of H. A path of H is a path of H having an endpoint in u and the other endpoint in v. Similarly, if U is a subgraph of H, then is the subgraph of H that results by removing U from H.

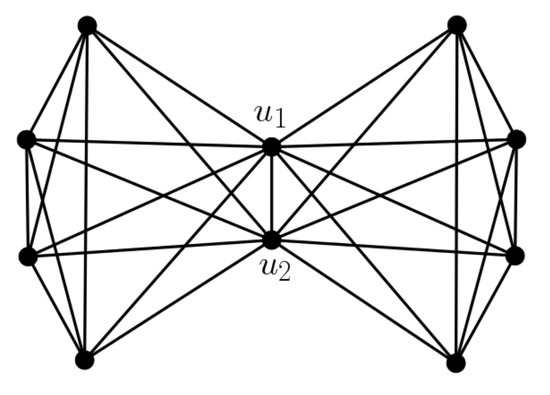

We recall that if k is a nonnegative integer, then H is k–connected if and is connected for every set with . The connectivity of H is greatest integer k such that H is k-connected. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

This graph is 2–connected, but not 3–connected. Indeed, if we remove any vertex, what remains is still connected. On the other hand, note that is vertex cut of order 2, and hence U is a vertex cut of minimum order.

Our aim in this paper is to show the following result.

Theorem 1.

Let P be a set of points in general positions in the plane. Then , and this bound is asymptotically tight.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The validity of inequality in Theorem 1 is proved in Section 2, by making strong use of the main result of Ábrego and Fernández-Merchant in [19]. In Section 3 we briefly explain the strategy to prove Theorem 1 and present the key ingredients of our proof. Finally, in Section 4, we show that the upper bound in Theorem 1 is asymptotically tight, by proving that for certain infinite family of point sets in general position with certain symmetry property.

2. The Rectilinear Local Crossing Number of and the Validity of Inequality in Theorem 1

In what follows n is an integer with , and P is an n-point set in general position. Our aim in this section is to show that . In order to do that, we need to establish a straightforward, yet essential, relationship between the minimum degree of the graph and the rectilinear local crossing number of the drawing of induced by P.

We recall that the rectilinear local crossing number of P denoted by , is the largest number of crossings on any element of , and that the rectilinear local crossing number of denoted by , is the minimum of taken over all n-point sets P in general position. See Figure 1 (upper right).

Proposition 2.

The minimum degree of the graph is equal to .

Proof.

Let be an element of , and let be the subset of consisting of all segments that cross e. From the definitions of e and it follows that an element of is adjacent to e in if and only if has both endpoints in and does not belong to . Since , then the degree of e in is exactly . The last fact and imply . On the other hand, from the definition of we know that contains a segment, say g, that is crossed by exactly elements of , and hence the degree of g in is , as required. □

The following result was proved in [19] and is the key ingredient in the proof of Corollary 4.

Theorem 3

(Theorem 1 [19]). If n is a positive integer, then

In addition, and .

Corollary 4.

Let P be an n-point set in general position, and let . Then .

Proof.

It is well-known that . Thus, it suffices to show that . A trivial manipulation of Equation (1) allow us to see that . On the other hand, from Proposition 2 and the fact that , it follows that , as required. □

3. The Key Ingredients of the Proof of Theorem 1

Our strategy to prove that the upper bound in Theorem 1 is asymptotically tight is as follows. First, for any integer n with , we define a certain n-point set in a general position, which we denote by . The family was originally defined by Lara, Rubio-Montiel and Zaragoza in [20], where it was shown that . More recently, Ábrego and Fernández-Merchant [19] showed that for any . Then, we will give some notation and basic facts related to the connectivity of , which will allow us to simplify the remaining part of the proof of Theorem 1. Finally, in Section 4.2, we will show that .

We now recall a couple of classical results in graph theory which are fundamental in our proof.

Theorem 5

(Hall’s theorem). Let H be a bipartite graph with bipartition , and let C be an element of of minimum cardinality. Then H contains a matching of size if and only if for any .

Theorem 6

(Menger’s theorem). A graph is k-connected if and only if it contains k pairwise internally disjoint paths between any two distinct vertices.

It is straightforward to check that the graph is connected for any n-point set P in general position with . In view of this, the following consequence of Menger’s theorem will be useful.

Corollary 7.

Let H be a connected graph. Then H is k-connected if and only if H has k pairwise internally disjoint paths, for any two vertices a and b of H such that .

Proof.

The forward implication follows directly from Menger’s theorem. Conversely, let U be a vertex cut of H of minimum order. Let and be two distinct components of , and let . Since U is a minimum cut, then u has at least a neighbor in , for . Then . By hypothesis, H has k pairwise internally disjoint paths. Since each of these k paths intersects U, then we have that , as required. □

Another ingredient that plays a central role in this work is the property of 3-symmetry of point sets in the plane, which is a recurrent concept in crossing number theory. A subset X in is called 3-symmetric if X contains a subset such that , where is a clockwise rotation around a suitable point in the plane. The relationship between the concept of 3-symmetry and several variants of crossing number have been investigated by a number of authors [19,20,21,22]. If X is finite and , then we say that X is almost 3-symmetric if X contains a subset with at most two elements such that is 3-symmetric. As we shall see in the next section, the main part of the proof of Theorem 1 is based on the estimation of the connectivity of , where is an almost 3-symmetric set with n points.

4. The Upper Bound in Theorem 1 Is Asymptotically Tight

For the rest of the paper, n is an integer with . We begin by introducing the family of point sets that we use in the proof of our main result, and some notation.

4.1. The Family and Its Properties

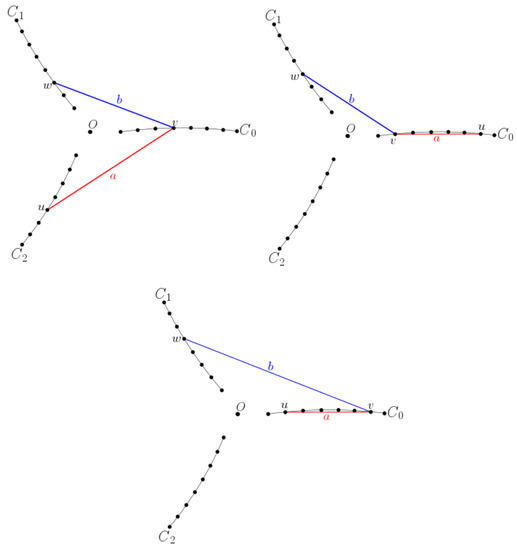

Following [19], let be the arc of the circumference passing through the points , and , where is close to zero. Let (resp. ) be the (resp. ) counterclockwise rotation of around the origin . We choose small enough so that any straight line passing through two distinct points of separates from . See Figure 3. Since is a 3-symmetric set, we can choose an almost 3-symmetric subset of Y with exactly n points. For , let . Then, , and for .

Figure 3.

The underlying point set in these three drawings is . Note that for each . The difference between these configurations is the way in which the endpoints of and are located on and .

For the rest of the paper, we use to denote the set of all segments of , and . Similarly, if , then will denote the maximum number of pairwise internally-disjoint paths in .

Remark 8.

Let be vertices of such that . By Corollary 7 and Menger’s theorem, in order to show the last assertion of Theorem 1 it is enough to show that .

In view of the previous remark, for the rest of the work, we can assume that a and b are two fixed vertices of such that . Then a and b are not adjacent in , and hence . This inequality and the fact that is a set in general position imply that consists precisely of one point of , which will be denoted by o. Then either a and b cross at o or o is common endpoint of them.

We note that if , then there is a unique such that e has an endpoint in and the other in , where addition is taken . We will say that such an i is the type of e. In particular, note that in any of the three cases of Figure 3, a and b are of type 0 and 1, respectively.

Clearly, there are only two possibilities for a and b with respect to their types: they have the same type, or they have different types. If a and b have the same type, then, by rotating around O (if necessary) but not the labels , and , we may assume that a and b are both of type 0. Analogously, if a and b have different types, then, by rotating (if necessary) we can assume that 0 and 1 are the types of a and b.

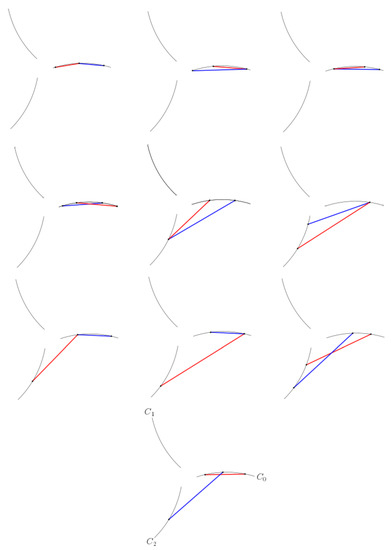

It is not hard to check that if a and b are of type 0 and 1, respectively, then the three configurations illustrated in Figure 3 are the only possibilities to put the endpoints of a and b on the arcs and . Similarly, if a and b are both of type 0, then ten configurations illustrated in Figure 4 are the only possibilities to put the endpoints of a and b on the arcs and . Then, from now on, we can assume without any loss of generality that a and b are placed in according to some case of Figure 3 and Figure 4. We abuse notation and we shall use to refer to the subset of points of that lies on the arc . In particular, we will assume that . For distinct , we let .

Figure 4.

Except for rotations, these ten configurations together with those three in Figure 3, are the only possibilities to put the endpoints of a and b on and . The arcs here are not as flat as they should be; we have drawn them in this way for illustrative purposes only.

We now split the set of neighbours of a and b into three sets as follows.

Clearly, and are pairwise disjoint. We also note that , and hence

Keeping in mind the facts and the terminology given in this subsection, we now proceed to show the last assertion of our main result.

4.2. Constructing the Required Paths of

As we have mentioned in Remark 8, all we need to finish the proof of Theorem 1 is to show the following lemma.

Lemma 9.

If a and b are as in Remark 8, then

We devote this section to show Lemma 9, and hence to complete the proof of Theorem 1. Our proof is constructive and uses two types of constructions, depending on whether a and b are located in according to some case of Figure 3 or Figure 4. In the interest of readability, we start by presenting several technical issues needed to define both types of constructions.

Since the equality in Lemma 9 is asymptotic, in what remains of this section, we assume that . Note that this assumption guarantees that each of and has at least one point that does not belong to a or b. This will be used in Section 4.2.2.

4.2.1. Suppose That a and b Have Distinct Types

Then, a and b are located in according to some case of Figure 3, and so and . Let H be the bipartite subgraph of with bipartition such that is adjacent to in H if and only if f and g are adjacent in . Thus, H is an induced bipartite subgraph of . If X and Y are nonempty subsets of , we will denote the set of all segments of that have an endpoint in X and the other in Y by .

A simple inspection of the several cases in which two elements of can cross each other yields the following assertion.

Observation 10.

If cross each other, then f and g are of the same type.

A key fact that will allow us to construct the first class of paths is that H satisfies the Hall’s condition. We formalize this idea as follows.

Proposition 11.

Let be an element of of minimum cardinality. Then for any .

Proof.

We break the proof into two cases, depending on whether or . We remark that Observation 10 is often used in this proof without explicit mention.

(A) Suppose that , and let . We can assume that and that , as otherwise we are done. Let be a fixed segment of , and assume that .

The next facts follow easily from the choice of and . (F1) intersects each element of , (F2) b intersects each element of , and (F3) each element of has at least one endpoint in .

(A1) Suppose that and . Then (F1) and (F3) imply that is a subset of , where denotes the set of all segments that intersect b and are in . Note that if , then , and so . Thus, we may assume that . This implies that if (respectively, ), then (respectively, ) is a subset of . Since and , we have .

(A2) Suppose that . Then (F1) and (F3) imply that is a subset of the set , which consists of all segments that intersect b and are in . Then, . Let , and assume without loss of generality that . Since , then and is a subset of . Then, , and we can assume that , as otherwise we are done. This implies that there exists with .

Since implies , we can assume that . Let be the set of points of that are between u and v. From (F1) we know that at most one of p or q is in . If is a point of , then is a subset of . Then , as required. Then, neither p nor q is in . Since , we must have . This implies that , and so .

(A3) Suppose that . Since is of type 2 and , then u must be a common endpoint of and a, by Observation 10. Without loss of generality, suppose that .

From (F1) and (F3) we know that is a subset of , where Y denotes the set of all points of that lie between u and q. Note that if u and q are consecutive points of , then . Let e be the segment of whose endpoint is closest to q. Let be the set of all points of that lie between u and . Then , and is a subset of . Since and , then implies .

(A4) Suppose that has an endpoint in . We assume without loss of generality that . Clearly, . Since , then , and so .

(A4.1) Suppose that . Then , and . Since , then due to (F1). Let , and let be the set that results by removing any segment of from . Then, because . We note that (F1) implies . If contains a segment e with both endpoints in , then (F1) implies , and hence , as required. Thus, we may assume that , and so .

Let be the set of points of that are between u and v (if u and v are contiguous, ), and let . By (F1) and (F2) we know that each segment of intersects both and b. Since b and are disjoint, no segment of can have an endpoint in , and, on the other hand, each segment of must have at least one endpoint in . Note that if has at least two points being incident with segments of , then each segment of is disjoint from at least one of these points of , and hence , as required.

Thus, we can assume that all segments of are incident with one point of , say z. Then, or , and so . On the other hand, note that , and so , as required.

(A4.2) Suppose now that . Then (F1), (F2), and (F3) imply that each segment of must be incident with at least one of p or w. Then, is the disjoint union and , where (respectively, ) denotes the subset of contained in (respectively, . Then, .

Let and . Clearly, and are disjoint sets. Moreover, by (A1) and (A3), we may assume that .

Suppose first that has no segments in . Then , and so . We may assume that , as otherwise we are done. Since , then we must have that and . From it follows that , and hence . Since and are pairwise disjoint, , as required.

Suppose now that has a segment e in . Then , and hence . Thus, we may assume that and , as otherwise we are done. Then, and .

From and (F2) it is not hard to see that must be the segment of with either the smallest or the largest length. Let . If is the segment of with the smallest (respectively, largest) length, then and (F1) imply that must have the largest (respectively, smallest) length among all segments in , and hence . Since and are pairwise disjoint and , then , as required.

(B) Suppose that , and let . We can assume that and that , as otherwise we are done. Let denote the ordinary euclidean distance in . For and , we let . The set is defined analogously. It is not hard to see that , where

Note that is a subset of . Since no segment of intersects every segment of , then at least one segment of is in , and so . Thus , as otherwise we are done.

(B1) Suppose that has two distinct segments of type 0, say and , so that . Then , unless . Since the former case contradicts , we assume that . Then , and hence , as required.

(B2) Suppose now that each segment of is incident with exactly one point . Clearly, . If , then , and hence . Since , then has at least two points, say and , such that . We note that , and so . Since , then .

Suppose now that . Then , and so . If has at least one segment in , then implies that , and so . Then, we may assume that has no segments in , and hence .

Let be the subset of all points in that are incident with a segment of . Then , and so . If , then , as required. Then we can assume that . Let be the point in that is farthest from w. Since any segment in is disjoint from , then is a subset of , and hence .

(B3) Suppose that . Let be the set of all segments of that are not incident with u. Suppose first that . Then (B1) implies that has at most one segment in . If there exists such that , then implies that , and hence . Thus, we may assume that . For , let be the subset of all points in that are incident with a segment of . Then , and so . If , then we use to denote the point in that is closest to w if (resp. u if ). Since any segment in is disjoint from at least one of or , then is a subset of , and hence .

Suppose now that . Then each segment of crosses a, and has at least one endpoint in . From (B2) it follows that there is such that . This fact and (B2) imply the existence of with . Note that if , then . On the other hand, if for some , then . In any case, we have .

(B4) Suppose that . Let be the set of all segments of in , and let . Then, any element in is a segment of type 0. We may assume that , as otherwise we are in (B1) or (B2) due to . Similarly, if , then . From we have that , and so . Thus, we also assume that .

From (B1) and we know that there exists a point that is incident with any segment of . Since and , then . Seeking a contradiction, suppose that . Since , then . From and it follows that has a segment with . Since e together with any other satisfy the conditions of (B1), then we must have that , contradicting . □

4.2.2. Suppose That a and b Have The Same Type

Then, a and b are located in according to some case of Figure 4. For let be the set of points in that are endpoints of at least one of a and b, and let . Then, . From a simple inspection of the ten cases in Figure 4 we can see that , , and . Thus, for the following holds:

Let be the subgraph of induced by , i.e., . Similarly, let

It is easy to check that and satisfy the following properties: (i) the three sets forming are pairwise disjoint, (ii) no segment of belongs to , (iii) , and (iv) a and b are vertices of .

By applying the main result of [14] to we have that the connectivity of is at least

where .

We are finally ready to prove Lemma 9.

Proof of Lemma 9.

Case 1. Suppose that a and b are located in according to some case of Figure 3, and let be as in Section 4.2.1. From Proposition 11 and Hall’s theorem it follows that H has a matching M of size . Suppose that Then

is a collection paths of of length 3. Furthermore, the paths in are pairwise internally disjoint, because M is a matching of H. On the other hand, note that

is also a collection of pairwise internally disjoint paths of of length 2. Since , then the paths in are pairwise internally disjoint. The existence of such paths, and (2) imply

Combining Proposition 2 and Theorem 3 we obtain that . Since , then (2) and (5) imply , as required.

Case 2. Suppose now that a and b are located in according to some case of Figure 4, and let and Properties (i)–(iv) as in Section 4.2.2.

Since , a straightforward manipulation on (4) gives that . This last equality, (iv), and Menger’s theorem imply that has collection of at least pairwise internally disjoint paths. On the other hand, from (iii) it follows that

is a collection of pairwise internally disjoint paths of of length 2. Moreover, by (ii) we have that is also a collection of pairwise internally disjoint paths of . From (3), (i), and the definition of , it is not hard to see that

Thus, . This last and (2) imply , as required. □

5. Concluding Remarks

Let P be a set of points in general position in the plane. We have observed that the minimum degree of the disjointness graph of segments defined by P can be expressed in terms of n and the rectilinear local crossing number of the rectilinear drawing of induced by P. From this observation and the exact value of provided by Theorem 1 in [19], it is easy to see that is an upper bound for , which is tight for each n. Since the connectivity of a graph H is upper bounded by its minimum degree , then is also a general upper bound for .

On the other hand, the main goal in this work is to estimate the connectivity of , where is one of the families of point sets best understood from the point of view of rectilinear crossing number. In particular, it is known that is almost 3-symmetric and that for each . The basic idea behind our approach is to show that cannot be too large. In fact, we strongly believe that holds, and that this equality can be verified by analogous arguments to those used in Section 4.2.1. We finally remark that Theorem 1 is an asymptotic solution for an open question posed in [14].

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous referees for careful reading and improvements to the presentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Araujo, G.; Dumitrescu, A.; Hurtado, F.; Noy, M.; Urrutia, J. On the chromatic number of some geometric type Kneser graphs. Comput. Geom. 2005, 32, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneser, M. Aufgabe 360, Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung. Abteilung 1955, 58, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lovász, L. Kneser’s conjecture, chromatic number, and homotopy. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 1978, 25, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárány, I. A short proof of Kneser’s conjecture. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 1978, 25, 325–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C. Kneser graphs are Hamiltonian for n ≥ 3k. J. Combin. Theory Ser. B 2000, 80, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, G.B.; Gauci, J.B. The super-connectivity of Kneser graphs. Discuss. Math. Graph Theory 2019, 39, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, M.O.; Boutin, D.L. Using determining sets to distinguish Kneser graphs. Electron. J. Combin. 2007, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matousěk, J. Using the Borsuk-Ulam theorem. In Lectures on Topological Methods in Combinatorics and Geometry; Anders, B., Günter, M.Z., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003; ISBN 3-540-00362-2. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Pabon, M.; Vera, J.-C. On the diameter of Kneser graphs. Discret. Math. 2005, 305, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinfeld, P. Chromatic Polynomials and the Spectrum of the Kneser Graph. Tech. rep., London School of Economics. LSE-CDAM-2000-02. 2000. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.27.4627 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Jonsson, J. The Exact Chromatic Number of the Convex Segment Disjointness Graph. 2011. Available online: https://people.kth.se/~jakobj/doc/preprints/chrom.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Fabila-Monroy, R.; Wood, D.R. The chromatic number of the convex segment disjointness graph. In Computational Geometry, Volume 7579 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fabila-Monroy, R.; Hidalgo-Toscano, C.; Leaños, J.; Lomelí-Haro, M. The Chromatic Number of the Disjointness Graph of the Double Chain. Discret. Math. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2020, 22, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Leaños, J.; Ndjatchi, C.; Ríos-Castro, L.R. On the connectivity of the disjointness graph of segments of point sets in general position in the plane. arXiv 2007, arXiv:2007.15127v1. [Google Scholar]

- Aichholzer, O.; Kynčl, J.; Scheucher, M.; Vogtenhuber, B. On 4–Crossing-Families in Point Sets and an Asymptotic Upper Bound. In Proceedings of the 37th European Workshop on Computational Geometry (EuroCG 2021), Saint Petersburg, Russia, 7–9 April 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pach, J.; Tardos, G.; Tóth, G. Disjointness graphs of segments. In 33th International Symposium on Computational Geometry (SoCG 2017) of Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs); Katz 59; Boris, A., Matthew, J., Eds.; Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik: Wadern, Germany, 2017; Volume 77, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pach, J.; Tomon, I. On the Chromatic Number of Disjointness Graphs of Curves. In 35th International Symposium on Computational Geometry (SoCG 2019); Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Wadern, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pach, J. Geometric Graph Theory, Surveys in Combinatorics, BOOK_CHAP. 1999, pp. 167–200. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/surveys-in-combinatorics-1999/geometric-graph-theory/E57E1273C7FAA8FD47B1B28F0E539C90 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Ábrego, B.M.; Fernández-Merchant, S. The rectilinear local crossing number of Kn. J. Combinat. Ser. A 2017, 151, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, D.; Rubio-Montiel, C.; Zaragoza, F. Grundy and pseudo–Grundy indices for complete graphs. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the XVI Spanish Meeting on Computational Geometry, Barcelona, Spain, 1–3 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ábrego, B.M.; Cetina, M.; Fernández-Merchant, S.; Leaños, J.; Salazar, G. 3-symmetric and 3–decomposable geometric drawings of Kn. Discret. Appl. Math. 2010, 158, 1240–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ábrego, B.M.; Cetina, M.; Fernández-Merchant, S.; Leaños, J.; Salazar, G. On ≤k-Edges, Crossings, and Halving Lines of Geometric Drawings of Kn. Discret. Comput. Geom. 2012, 48, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).