Abstract

A (legal) knight’s move is the result of moving the knight two squares horizontally or vertically on the board and then turning and moving one square in the perpendicular direction. A closed knight’s tour is a knight’s move that visits every square on a given chessboard exactly once and returns to its start square. A closed knight’s tour and its variations are studied widely over the rectangular chessboard or a three-dimensional rectangular box. For , an -ringboard or -annulus-board is defined to be an chessboard with the middle part missing and the rim contains r rows and r columns. In this paper, we obtain that a -ringboard with and has a closed knight’s tour if and only if (a) and or (b) and . If a closed knight’s tour on an -ringboard exists, then it has symmetries along two diagonals.

Keywords:

legal knight’s move; closed knight’s tour; open knight’s tour; Hamiltonian cycle; ringboard; annulus-board MSC:

05C38, 05C45, 05C90

1. Introduction

The chessboard or CB() is the generalization of the regular CB(). It consists of m rows of n arrays of squares. Suppose the squares of the CB() are labeled by in the matrix fashion. A legal knight’s move is the result of a moving the knight two squares horizontally or vertically on the CB() and then turning and moving one square in the perpendicular direction. That is, if we start at , then the knight can move to one of eight squares: or (if exists).

A closed knight’s tour (CKT) is a legal knight’s move that visits every square on a given chessboard exactly once and returns to its start square. While, an open knight’s tour (OKT) is a legal knight’s move that visits every square on a given chessboard exactly once and the starting and terminating squares are different. Both CKT and OKT problems on a two-dimensional or three-dimensional chessboard are one of the interesting mathematical problems as you can see some of them listed in [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Not only the legal knight’s move, but some researchers also extended it to be an -knight’s move which is the result of a moving the knight a squares horizontally or vertically on the CB() and then turning and moving b squares in the perpendicular direction. Several mathematical problems along this direction were considered, see for examples [7,8,9] and references therein for details.

In 1991, Schwenk [10] obtained necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of a CKT for the CB () as follows.

Theorem 1.

([10])A CB() with admits a CKT unless one or more of the following conditions holds: (i) is odd or (ii) or (iii) and . Furthermore, this CKT contains a knight’s move from square to square and square to square .

For the CB() that contains no CKTs, DeMaio and Hippchen [11] and Bullington et al. [12] can provide the minimal number of squares to be removed or to be added in order for the obtained new board to have a CKT. In particular, for or m and n are odd, Miller and Farnsworth [13] and Bi el al. [14] provided the exact position of a square to be removed from CB() so that the remaining board admits a CKT. However, for the case , the exact positions for two squares to be removed still open for researchers to explore.

In 2005, Chia and Ong [9] obtained necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of an OKT for the CB() as follows.

Theorem 2.

([9])A CB() with admits an OKT unless one or more of the following conditions holds: (i) or (ii) and or (iii) and .

In this article, we consider one of the variations of the CKT problem by considering the chessboard that the middle part is missing which is called -ringboard or -annulus board and we denote it by RB.

Definition 1.

Let m, n and r be integers such that . An RB is defined to be a CB() with the middle part missing and the rim containing exactly r rows and r columns.

In 1996, Wiitala [15] showed that the RB contains no CKT. However, the characterization of the general RB has not been given. Thus, we try to establish the characterization like the one given by Schwenk [10]. Actually, the CKT problem on the RB can be converted to a certain graph problem. If we regard each square of the RB as a vertex, then a knight graph represented all legal knight’s moves on RB is a graph with vertices and two vertices and are joined by an edge whenever the knight can be moved from one square to another by a legal knight’s move and this edge is denoted by . Then, a CKT (respectively, OKT) on the RB is a Hamiltonian cycle (respectively, Hamiltonian path) in . The following theorem is a necessary condition for the existence of a Hamiltonian path in a graph that we often use in this article.

Theorem 3.

([9])Let S be a proper subset of the vertex set of a graph G. If G contains a Hamiltonian path, then , where is the number of components in .

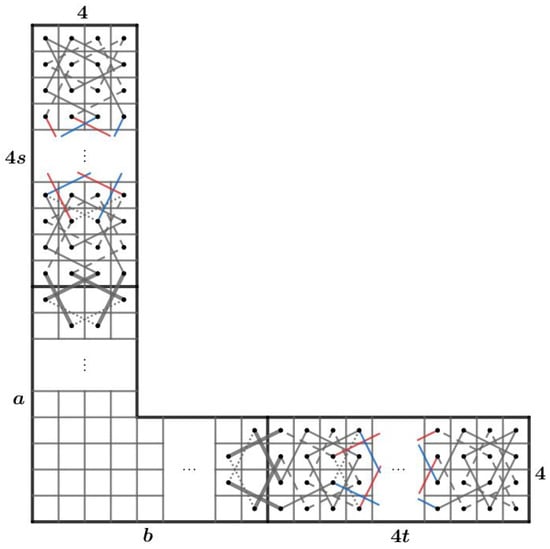

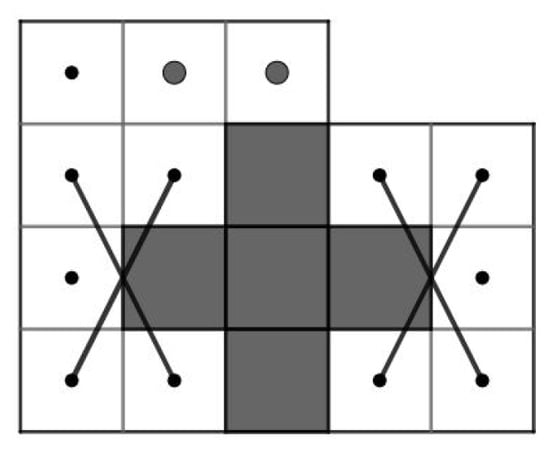

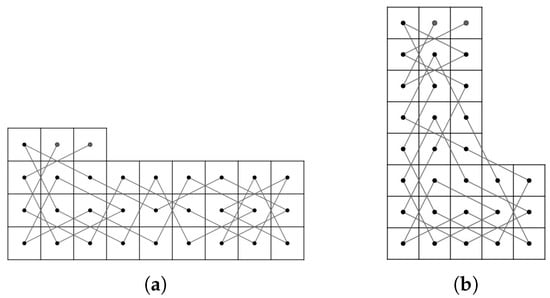

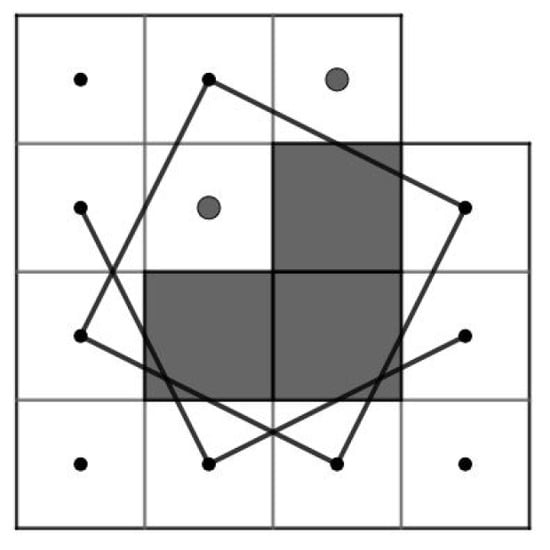

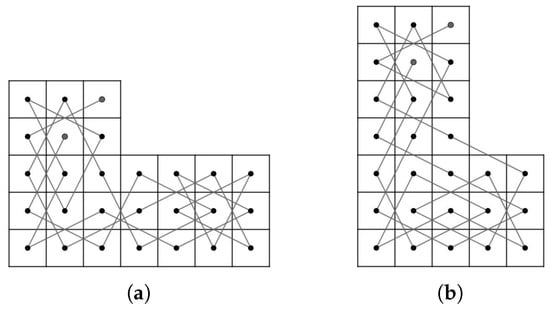

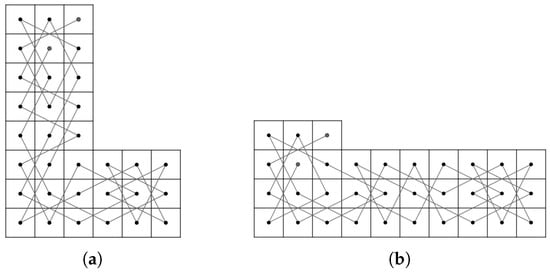

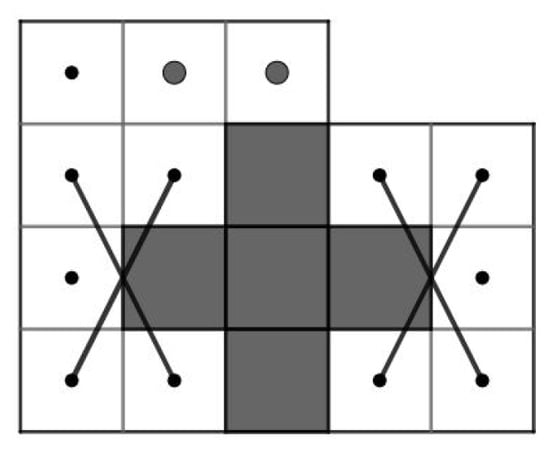

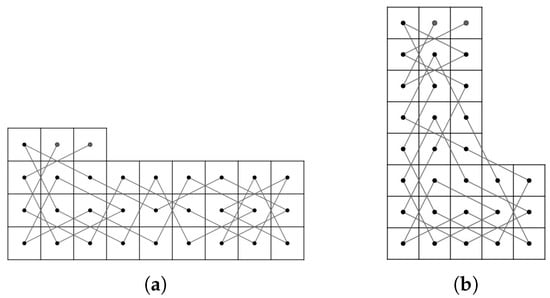

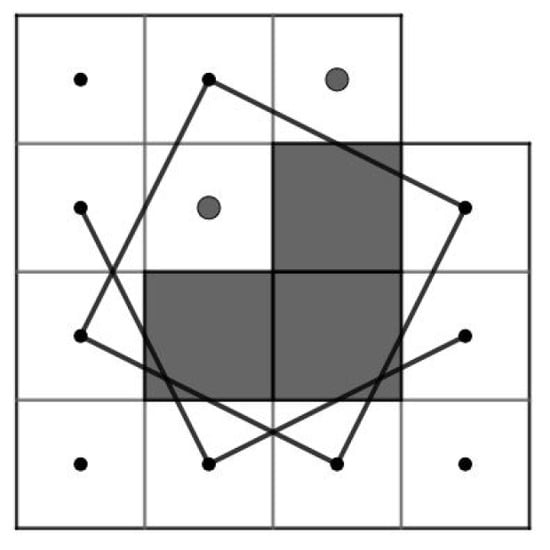

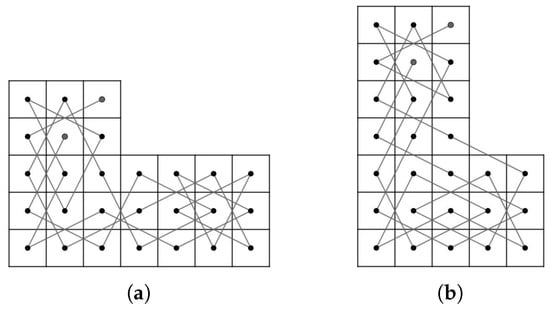

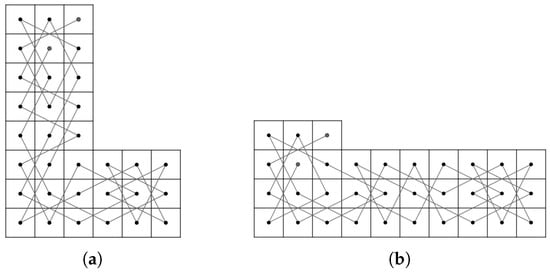

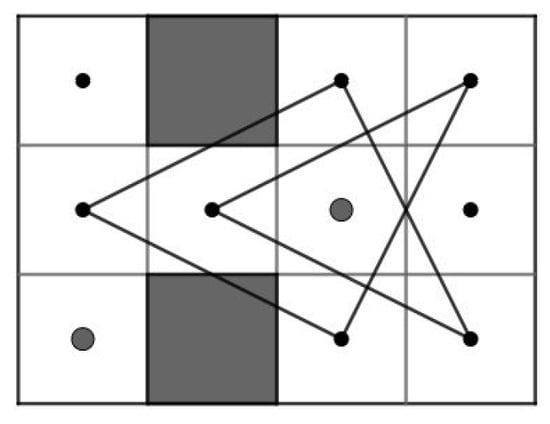

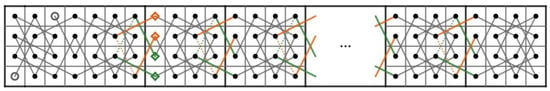

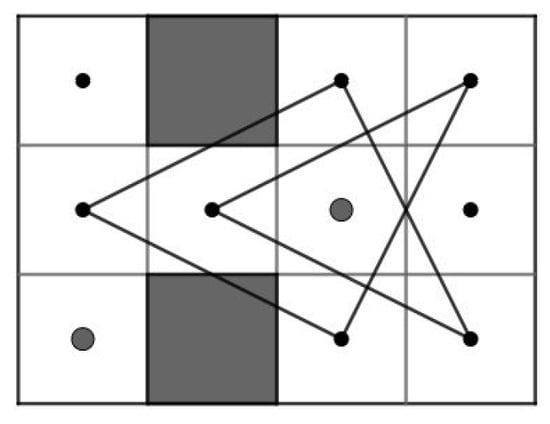

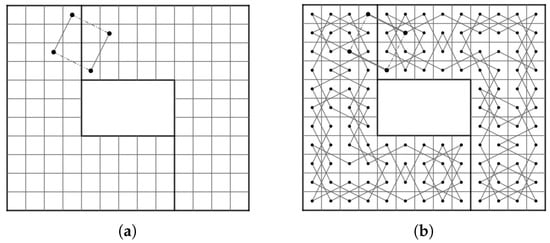

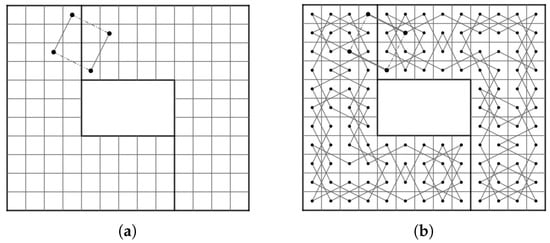

The goal of this article is to prove that for and , the RB admits a closed knight’s tour if and only if (a) and or (b) and . In order to reach our goal, we need to divide our RB into small pieces depending on r. If is even, then RB is divided into four smaller rectangular chessboard and we can use Theorem 1 to construct the CKT for RB which will be elaborated in Case 3.1 of Theorem 8 in Section 4. However, if is odd and RB is divided into four smaller rectangular chessboards, then there is a case that Theorem 1 cannot be used (Case 3.2 of Theroem 8). Thus, we need to construct our own CKT base on the existence of an OKT on some rectangular chessboards which will be constructed in Theorem 6 in Section 3. For small r, namely , we need to divide RB into two parts, namely an L-board and a 7-board of widths 3 or 4 which we denote by LB, LB, 7B and 7B depending on the numbers of row r and columns c (See Cases 1 and 2 of Theorem 8). For example, Figure 1 illustrates that RB is divided into LB and 7B and RB is divided into LB and 7B.

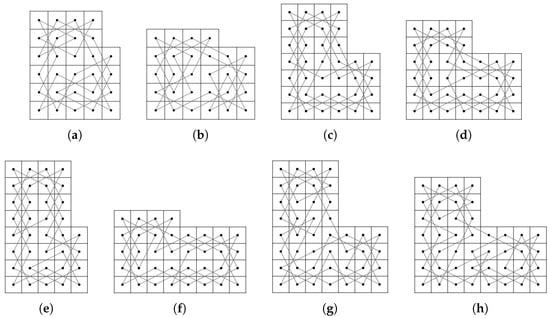

Figure 1.

LB, 7B, LB and 7B.

Therefore, to construct the CKT on the ringboard for this case, we prove the existence of a CKT on LB and 7B and the existence of some OKTs on LB and 7B are given in Theorems 4 and 5 in Section 2. For , we prove the extension of Wiitala’s result in [15] which is the non-existence of the CKT on the RB in Theorem 7 in Section 4. Finally, the conclusion and discussion about our future research are in Section 5.

2. CKTs and OKTs on Some LBs and 7Bs

First, let us construct the CKT on LB, where .

Theorem 4.

An LB has a CKT containing an edge for all .

Proof.

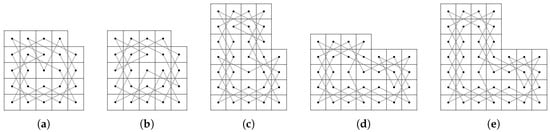

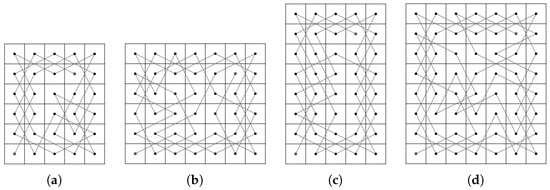

First, let us construct CKTs on some small size LBs of the same and different parity of m and n as in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

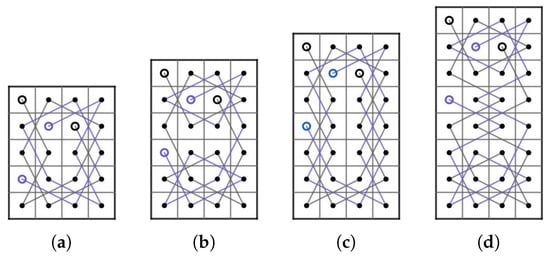

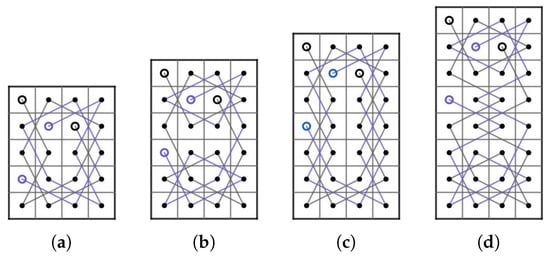

Figure 2.

Closed knight’s tours (CKTs) for LB, LB, LB and LB.

Figure 3.

CKTs for LB, LB, LB and LB.

Figure 4.

CKTs for LB, LB, LB, LB, LB, LB, LB and LB.

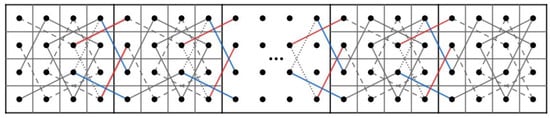

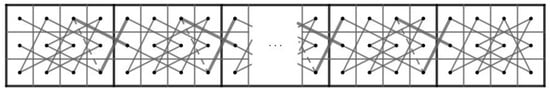

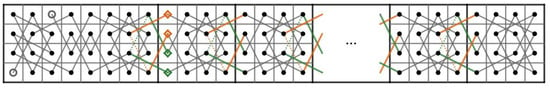

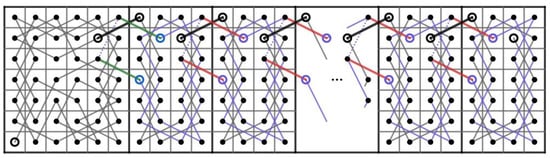

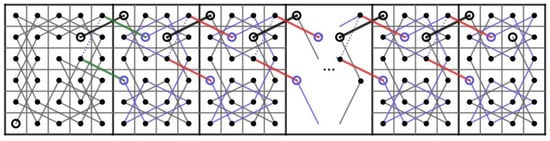

Next, for the larger LBs, we start by constructing two paths (dash line) and (solid line) on the CB() as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Two paths and on the CB().

Then, we construct two paths and on the CB() where . Let us connect t CB()’s in Figure 5 to the right of each other and do the following.

- (i)

- For , delete from and from of the ith CB().

- (ii)

- For , join and of the ith CB() to and of the th CB(), respectively

- (iii)

- For , join and of the ith CB() to and of the th CB(), respectively.

Notice that , , and are four end-points of two paths of the CB() for . By rotating Figure 5 and Figure 6 counter-clockwise by 90 degrees, we also obtain two paths and on the CB() where as shown in Figure 7. Notice also that , , and are four end-points of two paths and the edge contained in one path of the CB() for .

Figure 6.

Two paths and on the CB().

Figure 7.

Two paths and on the CB().

Now, we are ready to construct a CKT on a larger LB by placing the CB() to the right and the CB() above each smaller LB that we have considered before, respectively. WLOG, let .

- If m and n are odd integers, then or 3 (mod 4) and or 3 (mod 4).

- If m and n are even integers, then or 2 (mod 4) and or 2 (mod 4).

- If m and n are different parity, then or 3 (mod 4) and or 2 (mod 4); and or 2 (mod 4) and or 3 (mod 4).

Recall that the LB has a CKT for all . In addition, from Figure 2b–e, Figure 3 and Figure 4, each CKT of the LB contains edges , , and . Furthermore, from Figure 2a,c–e, Figure 3 and Figure 4, each CKT of the LB contains the edge .

Thus, it is enough to show that the LB has a CKT for any nonnegative and such that and . First, if , then let us divide the LB into two subboards, CB() and LB. Otherwise, we divide into three subboards, CB(), LB and CB(). Then, we construct the required CKT by the followings.

- (i)

- if , then delete and from the CKT of the LB. If , then further delete and from the CKT of the LB.

- (ii)

- If , then join , , and which are four end-points of two paths of the CB() to , , and of the LB, respectively. If , then further join , , and which are four end-points of two paths of the CB() to , , and of the LB, respectively.

Figure 8 illustrates the constructed CKT on the LB. This completes the proof. □

Figure 8.

A CKT on the LB.

By properly rotating and flipping the LB, where , we obtain the following result immediately.

Corollary 1.

A 7B has a CKT containing an edge for all .

We note that Theorem 4 and Corollary 1 will be used in Case 2 of Theorem 8 in Section 4. Next, we construct two OKTs for the LB and two OKTs for the 7B for .

Theorem 5.

Let .

- (a)

- The LB contains an OKT from to if and only if (i) is odd and or (ii) and .

- (b)

- The LB contains an OKT from to if and only if (i) is even and or (ii) and .

Proof.

Let .

(a) We assume that the LB contains an OKT from to and let is even; or and ; or and .

If is even, then the numbers of white squares and black squares are not the same. Thus, the two end-points of this OKT must have the same color. However, and are next to each other and have different colors, which is a contradiction.

Let or and . By the above argument must be odd and since , we have which implies that and .

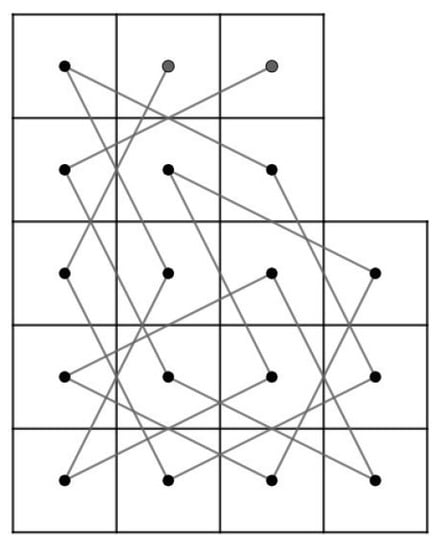

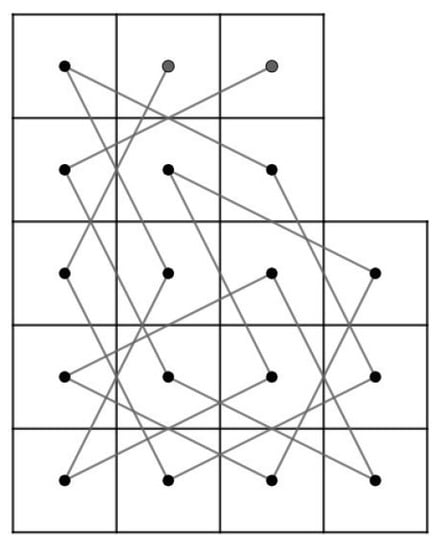

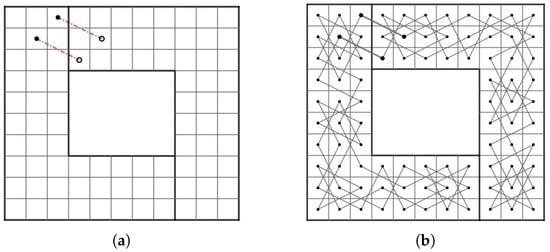

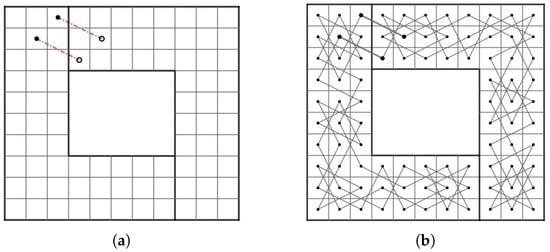

For and , let G be a knight graph of the LB. Consider . Since the LB contains an OKT from to , has a Hamiltonian path. Let . Then, as shown in Figure 9. By Theorem 3, we obtain a contradiction.

Figure 9.

Components of .

On the other hand, let us assume that is odd and ; or and .

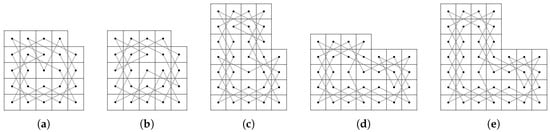

If and , then the required OKT presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Required open knight’s tour (OKT) on the LB.

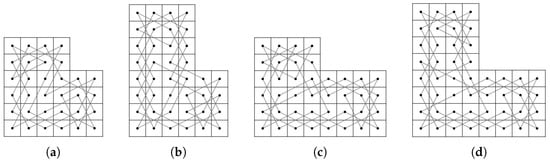

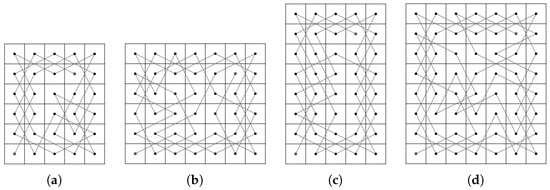

If is odd and , we construct OKTs on some small LB according to the remainders of m and n after divided by 4 as the following Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

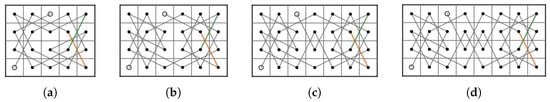

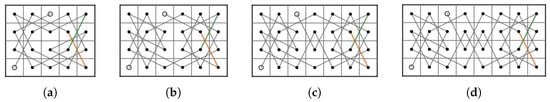

Figure 11.

OKTs on the LB and LB.

Figure 12.

OKTs on the LB and LB.

Figure 13.

OKTs on the LB and LB.

Figure 14.

OKTs on the LB and LB.

Next, for the larger LB, we start by constructing an OKT on CB() from to that contains an edge as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

An OKT on CB().

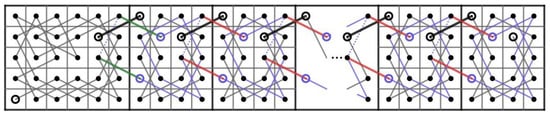

Then, we construct an OKT on the CB(), where . Let us connect t CB()’s in Figure 15 to the right of each other and do the following.

- (i)

- For , delete from the OKT of the ith CB();

- (ii)

- For , join and of the ith CB() to and of the th CB(), respectively.

By rotating Figure 16 clockwise for 90 degrees, we also obtain an OKT on CB() from to as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 16.

An OKT on CB().

Figure 17.

An OKT on CB().

Now, we are ready to construct an OKT on a larger LB by placing the CB() to the right and the CB() above each smaller LB that we have considered before, respectively.

- Case 1: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . We divided the LB into subboards, CB() (Figure 17) and LB (Figure 11a) if and and LB (Figure 11a) and CB() (Figure 16) if and . Otherwise, we divide into three subboards, CB() (Figure 17), LB (Figure 11a) and CB() (Figure 16). Then, we construct the required OKT by the following two steps.

- (i)

- (ii)

- If and , then join and of the CB() to and of the LB, respectively. If and , then join and of the LB to and of the CB() chessboard, respectively. Otherwise, join four pairs of vertices together.

- Case 2: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 11b), and , respectively.

- Case 3: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 12a), and , respectively.

- Case 4: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 12b), and , respectively.

- Case 5: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 13a), and , respectively.

- Case 6: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 13b), and , respectively.

- Case 7: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 10), and , respectively.

- Case 8: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 14a), and , respectively.

- Case 9: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 14b), and , respectively.

(b) We assume that the LB contains an OKT from to and let is odd; or and ; or and .

If is odd, then the numbers of white squares and black squares are the same. Thus, the two end-points of this OKT must have the different color. However, and have the same color, a contradiction. Next, we consider the cases that and ; or and ; or and .

For and , let be a knight graph of the LB. Consider . Since the LB contains an OKT from to , has a Hamiltonian path. Let . Then, as shown in Figure 18. By Theorem 3, we obtain a contradiction.

Figure 18.

Components of .

For and , let be a knight graph of the LB. Consider . Since the LB contains an OKT from to , has a Hamiltonian path. Let . Then, as shown in Figure 19. By Theorem 3, we obtain a contradiction.

Figure 19.

Components of .

For and , let be a knight graph of the LB. Consider . Since the LB contains an OKT from to , has a Hamiltonian path. Let . Then, as shown in Figure 20. By Theorem 3, we obtain a contradiction.

Figure 20.

Components of .

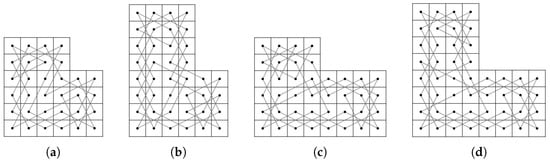

On the other hand, let us assume that is even and ; or and .

If and , then the required OKT is presented in Figure 21.

Figure 21.

Required OKT on the LB.

If is even and , we construct OKTs on some small LB according to the remainders of m and n after divided by 4 as the following Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26 and Figure 27.

Figure 22.

OKTs on the LB and LB.

Figure 23.

An OKT on the LB.

Figure 24.

OKTs on the LB and LB.

Figure 25.

An OKT on the LB.

Figure 26.

OKTs on the LB and LB.

Figure 27.

OKTs on the LB and CB.

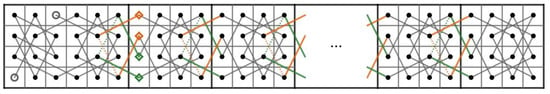

Next, for the larger LB, we start by constructing an OKT on CB() from to and contains an edge as shown in Figure 28.

Figure 28.

An OKT on CB().

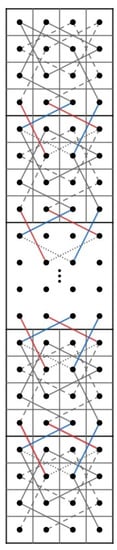

Then, we construct two paths on CB(), where . Let us connect s CB()’s in Figure 28 on the top of each other and do the following.

- (i)

- For , delete from the OKT of the ith CB();

- (ii)

- For , join and of the ith CB() to and of the th CB(), respectively.

We can see from Figure 29 that either s is odd or s is even, there is one path that has as its end-point and another path that has as its end-point.

Figure 29.

Two paths on chessboard.

Now, we are ready to construct an OKT on a larger LB by placing the CB() in Figure 16 to right and the CB() above each smaller LB that we have considered before, respectively.

- Case 1: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . We divide the LB into subboards, CB() (Figure 29) and LB (Figure 22a) if and and LB (Figure 22a) and CB() (Figure 16) if and . Otherwise, we divide into three subboards, CB() (Figure 29), LB (Figure 22a) and CB() (Figure 16). Then, we construct the required OKT by the followings.

- Case 2: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 22b), and , respectively.

- Case 3: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 23), and , respectively.

- Case 4: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 24a), and , respectively.

- Case 5: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 24b), and , respectively.

- Case 6: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 25), and , respectively.

- Case 7: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 26a), and , respectively.

- Case 8: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 26b), and , respectively.

- Case 9: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 21), and , respectively.

- Case 10: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 27a), and , respectively.

- Case 11: there exist nonnegative integers such that and . Then, we construct the required OKT by using the same procedure as we did in Case 1 but LB, and are replaced by LB (Figure 27b), and , respectively.

This completes the proof. □

Next, we get the following Corollary by flipping and rotating 90 degrees clockwise the LB in the above Theorem.

Corollary 2.

Let .

- (a)

- The 7B contains an OKT from to if and only if (i) is odd and or (ii) and .

- (b)

- The 7B contains an OKT from to if and only if (i) is even and or (ii) and .

3. Existence of a Special OKT on CB()

The following theorem gives necessary and sufficient conditions on the existence of a special OKT on CB() from to . This OKT will be used to prove our main result for when r is odd (Case 3.2 of Theorem 8 in Section 4).

Theorem 6.

- (a)

- Let and . Then, a CB() contains an OKT from to if and only if and .

- (b)

- Let . Then, a CB() contains an OKT from to if and only if m and n are not both even.

Proof.

(a) Let . We assume that a CB() contains an OKT from to and let ; or . Then, we consider 4 cases as follows.

Case 1: and or and or and . A CB() contains no OKT by using Theorem 2, contradiction.

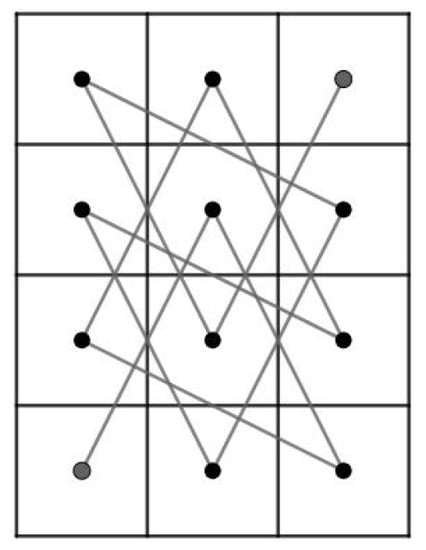

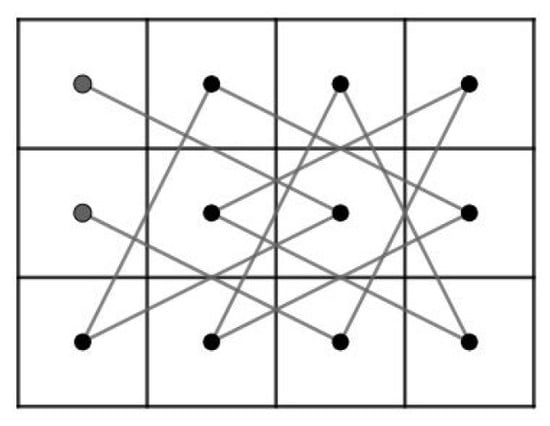

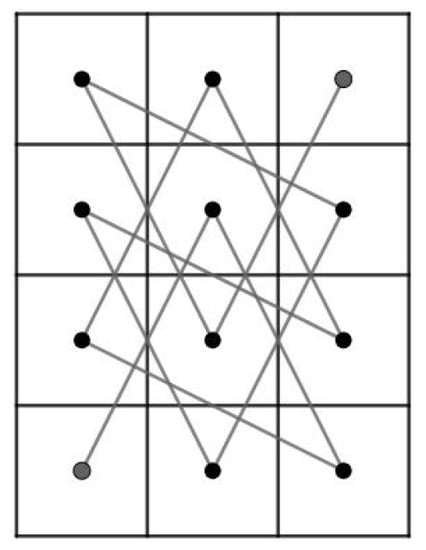

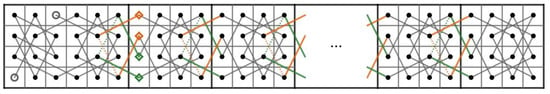

Case 2: For and , let be a knight graph of the CB(). We assume that contains a Hamiltonain path from to . Consider . By assumption, has a Hamiltonian path. Let . Then, as shown in Figure 30. By Theorem 3, we obtain a contradiction.

Figure 30.

Components of .

Case 3: For and n is odd such that . Let be a knight graph of the CB(). We assume that contains a Hamiltonian path from to . Consider . Let . Then, we can use mathematical induction to show that as shown in Figure 31. By Theorem 3, we have a contradiction.

Figure 31.

Components of , where .

Case 4: For and n is even such that . Assume that CB() contains an OKT from to . Since CB() contains the same numbers of black and white squares, this OKT must have end-points at two squares with different color. However, and are odd. Thus, and are two squares of the same color, contradiction.

On the other hand, let us assume that and .

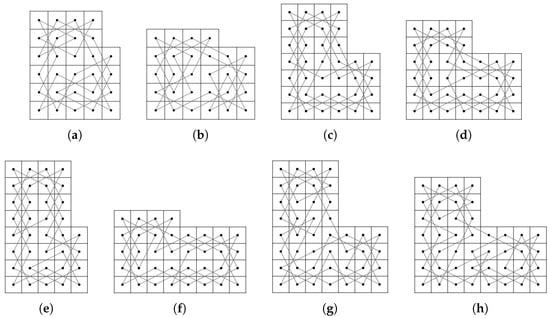

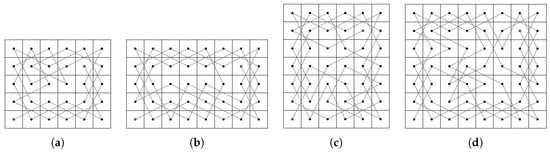

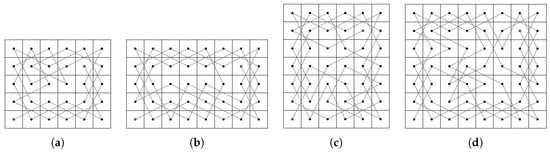

Let us construct OKTs from to on some small size CB() where as shown in Figure 32.

Figure 32.

OKTs from to on the CB() where .

Before we continue further, let us rotate the CB() shown in Figure 28 for 90 degrees clockwise and flip it to obtain an OKT from to on CB(). We can place t of these CB() to the right of each other to extend this OKT into an OKT on CB() by connecting on the ith CB() to on the th CB() for all as shown in Figure 33. Note that this extended OKT starts from to .

Figure 33.

An OKT from to on CB().

Next, let n be a positive integer such that .

If (mod 4) (respectively, (mod 4), (mod 4), (mod 4)), then there is a positive integer t such that (respectively, ). We divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 33) and CB() (Figure 32a) (respectively, CB() (Figure 32b), CB() (Figure 32c), CB() (Figure 32d)). Then, we construct the required OKT by connecting of the OKT on the CB() in Figure 33 to of the OKT on the CB() in Figure 32a (respectively, CB() in Figure 32b, CB() in Figure 32c, CB() in Figure 32d).

(b) Let . We assume that a CB() contains an OKT from to and let m and n are both even. Since CB() contains the same numbers of black and white squares, this OKT must have end-points at two squares with different colors. However, and are odd. Thus, and are two squares of the same color, contradiction.

On the other hand, let us assume that m and n are not both even such that . Then, we consider three cases as follows.

Case 1:m and n are both odd such that . Let us construct OKTs from to containing the edge on some small size CB() where as shown in Figure 34.

Figure 34.

OKTs from to on the CB() where .

For the larger CB(), we start by constructing two paths on CB(). The first path starts from to and the second path starts from to where as shown in Figure 35.

Figure 35.

Two paths on CB() where .

Next, we construct an OKT from to containing the edges and on the CB() where as shown in Figure 36.

Figure 36.

OKTs on CB() where .

Let be odd integers such that and .

Case 1.1: (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 34a) and t CB()’s (Figure 35a). Then, we construct the required OKT by the followings.

- (i)

- We delete of the OKT on the CB() and connect and of the CB() to and of the 1st CB(), respectively.

- (ii)

- We delete of the second path of the ith CB() for all . Then, we connect and of the ith CB() to and of the th CB().

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 37) and s CB()’s from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by the followings.

Figure 37.

An OKT on CB() in Case 1.1.

- (i’)

- For each , we divide the ith CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 36a) and CB() (Figure 6). Delete and of the OKT on CB(). Then, join and of the CB() to and of the CB(), respectively, to obtain an OKT on the CB() as shown in Figure 38.

Figure 38. An OKT on CB() in Case 1.1.

Figure 38. An OKT on CB() in Case 1.1. - (ii’)

- Join of the OKT on CB() to of the 1st CB() shown in Figure 38.

- (iii’)

Case 1.2: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 34b) and t CB()’s (Figure 35a). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() by CB() (Figure 34b) and , and by , and , respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 39) and s CB()’s (Figure 40) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (i’) replace CB() by CB() (Figure 36c) and , , and by , , and , respectively.

Figure 39.

An OKT on CB() in Case 1.2.

Figure 40.

An OKT on CB() in Case 1.2.

Case 1.3: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 34c) and t CB()’s (Figure 35c). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 34c) and CB() (Figure 35c), respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 41) and s CB() (Figure 38) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (ii’) replace CB() by CB() (Figure 41) and by .

Figure 41.

An OKT on CB() in Case 1.3.

Case 1.4: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 34d) and t CB()’s (Figure 35c). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 34d) and CB() (Figure 35c)) and , and by , and , respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 42) and s CB()’s (Figure 40) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (i’) and (ii’) replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 36c) and CB() (Figure 42) and replace , , , and by , , , and , respectively.

Figure 42.

An OKT on CB() in Case 1.4.

Case 2:m is odd such that and n is even such that . Let us construct OKTs from to containing the edge on some small size CB() where and as shown in Figure 43.

Figure 43.

OKTs from to on the CB() where and .

Let m be an odd integer such that and let n be an even integer such that .

Case 2.1: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 43b) and t CB()’s (Figure 35a). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() by CB() (Figure 43b) and , and by , and , respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 44) and s CB()’s (Figure 45) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (i’) replace CB() by CB() (Figure 36d) and , , and by , , and , respectively.

Figure 44.

An OKT on CB() in Case 2.1.

Figure 45.

An OKT on CB() in Case 2.1.

Case 2.2: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 43a) and t CB()’s (Figure 35a). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() by CB() (Figure 43a) and , and by , and , respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 46) and s CB()’s (Figure 47) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (i’) replace CB() by CB() (Figure 36b) and , , and by , , and , respectively.

Figure 46.

An OKT on CB() in Case 2.2.

Figure 47.

An OKT on CB() in Case 2.2.

Case 2.3: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 43d) and t CB()’s (Figure 35c). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 43d) and CB() (Figure 35c) and , and by , and , respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 48) and s CB()’s (Figure 45) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (i’) and (ii’) replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 36d) and CB() (Figure 48) and , , and by , , and , respectively.

Figure 48.

An OKT on CB(.) in Case 2.3.

Case 2.4: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 43c) and t CB()’s (Figure 35c). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1. but replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 43c) and CB() (Figure 35c) and , and by , and , respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 49) and s CB()’s (Figure 47) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1. but in (i’) and (ii’) replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 36b) and CB() (Figure 49) and , , , and by , , , and , respectively.

Figure 49.

An OKTs on CB() in Case 2.4.

Case 3:m is even such that and n is odd such that . Let us construct OKTs from to containing the edge on some small size CB() where and as shown in Figure 50.

Figure 50.

OKTs from to on the CB() where and .

Let m be an even integer such that and let n be an odd integer such that .

Case 3.1: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 50c) and t CB() (Figure 35d). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 50c) and CB() (Figure 35d), respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 51) and s CB()’s (Figure 38) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (ii’) replace CB() by CB() (Figure 51) and by .

Figure 51.

An OKTs on CB() in Case 3.1.

Case 3.2: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 50d) and t CB()’s (Figure 35d). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 50d) and CB() (Figure 35d) and , and by , and , respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 52) and s CB()’s (Figure 40) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (i’) and (ii’) replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 36c) and CB() (Figure 52) and , , , and by , , , and , respectively.

Figure 52.

An OKT on CB() in Case 3.2.

Case 3.3: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 50a) and t CB() (Figure 35b). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 50a) and CB() (Figure 35b), respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 53) and s CB()’s (Figure 38) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (ii’) replace CB() by CB() (Figure 53) and by .

Figure 53.

An OKT on CB() in Case 3.3.

Case 3.4: (mod 4) and (mod 4). There are integers s and t such that , , and . If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 50b) and t CB() (Figure 35b). Then, we construct the required OKT by (i) and (ii) in Case 1.1 but replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 50b) and CB() (Figure 35b) and , and by , and , respectively.

If , then we divide the CB() into subboards, CB() (Figure 54) and s CB()’s (Figure 40) from the top to the bottom. Then, we construct the required OKT by (i’), (ii’) and (iii’) in Case 1.1 but in (i’) and (ii’) replace CB() and CB() by CB() (Figure 36c) and CB() (Figure 54) and , , , and by , , , and , respectively.

Figure 54.

An OKT on CB() in Case 3.4.

This completes the proof. □

4. Main Theorem

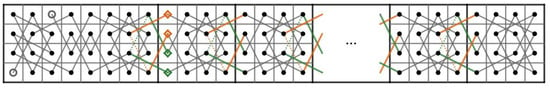

To characterize the RB according to the existence of its CKT, let us first consider the case when . It is known from Wiitala [15] that RB admits no CKTs. The following theorem can be regarded as an extended result of Wiitala [15]. Recall that is the knight graph of the RB.

Theorem 7.

There are no CKT on RB for all .

Proof.

Let m and n be integers such that . Then, there exist positive integers k and l and such that and . Assume that there exists a CKT H on RB() which is a Hamiltonian cycle on .

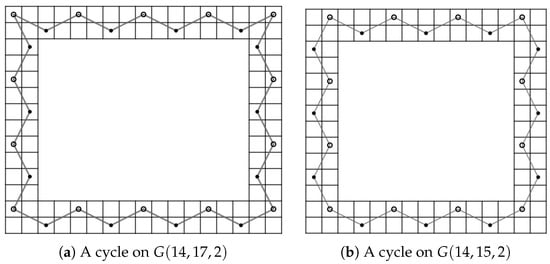

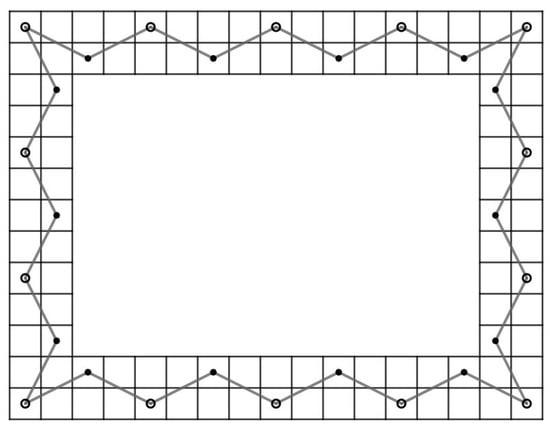

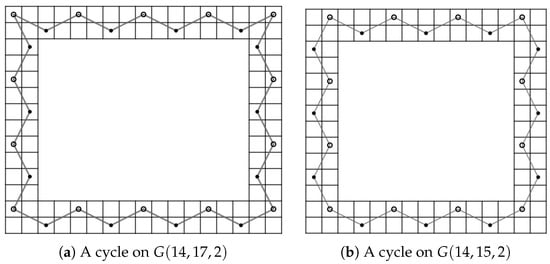

Case 1: and . Since all vertice in and have only 2 incident edges and we collect all incident edges from these two sets, it happens to form a cycle , , , , … , , , , , , … , , , , , , … , , , , , , … , , , see Figure 55 for a cycle on . This is a contradiction since this cycle does not contain all vertices of .

Figure 55.

A cycle on .

Case 2: and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 56a for a cycle on .

Figure 56.

Cycles on , , , and , respectively.

Case 3: and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 56b for a cycle on .

Case 4: and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 56c for a cycle on .

Case 5:, and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 56d for a cycle on .

Case 6:, and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 56e for a cycle on .

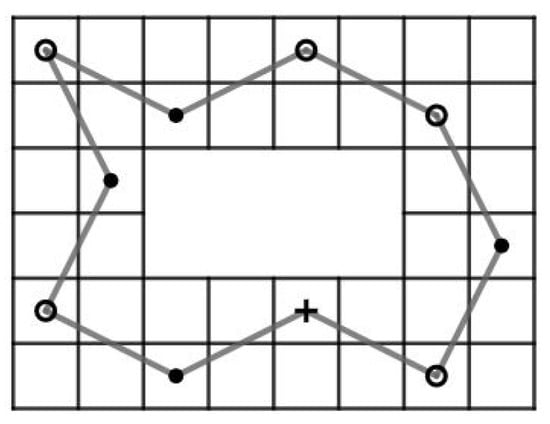

Case 7:, and .

If , then there are some vertices (i.e., and which are indicated by “+” in Figure 57) that have degree more than the degree of the same vertices in the case when .

Figure 57.

A cycle on .

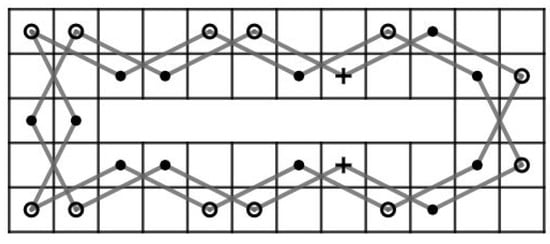

Case 7.1:. Since and have only 2 incident edges on the , and must be in H and it forces that and must not be in H. Then, it also forces that , , and must be in H. Next, since all vertice in , and have only 2 incident edges. Collect , , and which must be in H together with all incident edges from these three sets, it happen to form a cycle , , , , … , , , , , , , … , , , , , , , … , , , , , , , … , , , , , , see Figure 57 for a cycle on . This is a contradiction since this cycle does not contain all vertices of .

Case 7.2:. We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering , and instead, see Figure 58 for a cycle on .

Figure 58.

A cycle on .

Case 8:, and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 59a for a cycle on .

Figure 59.

Cycles on and , respectively.

Case 9:, and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 59b for a cycle on .

Case 10:, and .

If and , then it is similar to Case 7.1. We can see that (indicated by “+” in Figure 60) has degree 3 which is more than the degree of the same vertex in the case when and .

Figure 60.

A cycle on .

Case 10.1: and . Since and have only 2 incident edges on the , and must be in H and it forces that must not be in H. Then, it also forces that and must be in H. Next, since all vertice in have only 2 incident edges. Collect and which must be in H and together with all incident edges from the set , it happens to form a cycle , , , , , , , , , , , see Figure 60. This is a contradiction since this cycle does not contain all vertices of .

Case 10.2: and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering , , and instead, see Figure 61 for a cycle on .

Figure 61.

A cycle on .

Case 11:, and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 62a for a cycle on .

Figure 62.

Cycles on and , respectively.

Case 12:, and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering and instead, see Figure 62b for a cycle on .

Case 13:, and .

If and or and , then it is similar to Case 7.1. For and , there are some vertices (i.e., , , and which are indicated by “+” in Figure 63) that have a higher degree than the degree of the same vertices in the case when . For and , there are some vertices (i.e., and which are indicated by “+” in Figure 64) that have degree more than the degree of the same vertices in the case when .

Figure 63.

A cycle on .

Figure 64.

A cycle on .

Case 13.1: and . Since , , and have only 2 incident edges on , , , and must be in H and it forces that and must not be in H. Then, it also forces that , , and must be in H. Thus, and already have two incident edges on H and it forces again that and must not be in H. Next, since all vertice in have only 2 incident edges. Collect , , and which must be in H together with all incident edges from , it happens to form a cycle , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , see Figure 63. This is a contradiction since this cycle does not contain all vertices of .

Case 13.2: and . Since , , and have only 2 incident edges on , , , and must be in H and it forces that and must not be in H. Then, it also forces that , , and must be in H. Next, since all vertice in , and have only 2 incident edges. Collect and which must be in H together with all incident edges from these two sets, it happen to form a cycle , , , …, , , , , , , …, , , , , , , , …, , , , , , , , , , …, , , , , , see Figure 64 for a cycle on . This is a contradiction since this cycle does not contain all vertices of .

Case 13.3:. We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering , , , , , and instead, see Figure 65 for a cycle on .

Figure 65.

A cycle on .

Case 14:, and .

If , then it is similar to Case 7.1. There are some vertices (i.e., and which are indicated by “+” in Figure 66) that have degree more than the degree of the same vertices in the case when .

Figure 66.

A cycle on .

Case 14.1:. Since , , and have only 2 incident edges on , , , and must be in H and it forces that and must not be in H. Then, it also forces that and must be in H. Next, since all vertice in , and have only 2 incident edges. Collect and which must be in H together with all incident edges from these three sets, it happens to form a cycle , , , …, , , , , , , , …, , , , , , , , …, , , , , , , , …, , , , , , see Figure 66 for a cycle on . This is a contradiction since this cycle does not contain all vertices of .

Case 14.2:. We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering , , , and instead, see Figure 67 for a cycle on .

Figure 67.

A cycle on .

Case 15:, and .

If and , then it is similar to Case 7.1. The vertex (indicated by “+” in Figure 68) has degree 3 which is more than the degree of the same vertex in the case when and .

Figure 68.

A cycle on .

Case 15.1: and . Since and have only 2 incident edges on , and must be in H and it forces that must not be in H. Then, it also forces that and must be in H. Next, since all vertice in and have only 2 incident edges. Collect and which must be in H together with all incident edges from these two sets, it happens to form a cycle , , , …, , , , , , , , , …, , , , , , see Figure 68 for a cycle on . This is a contradiction since this cycle does not contain all vertices of .

Case 15.2:. We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering , , and instead, see Figure 69 for a cycle on .

Figure 69.

A cycle on .

Case 16:, and . We obtain a contradiction similar to Case 1 by considering , , , , , and instead, see Figure 70 for a cycle on .

Figure 70.

A cycle on .

This completes the proof. □

Now, we are ready to prove our main theorem about the existence of a CKT on RB.

Theorem 8.

An RB with and has a CKT if and only if (a) and or (b) and .

Proof.

First, for , and , the degree of four conner vertices of is at most one. Thus, RB cannot have CKT. For and , By the result of Wiitala [15] and Theorem 7, an RB has no CKT.

Conversely, for and , it is well-known that an RB has a CKT. Next, we assume that and .

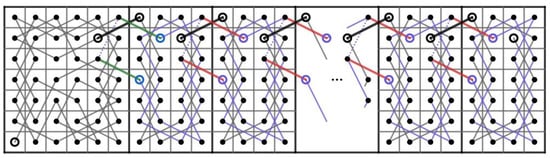

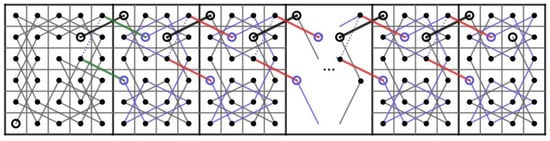

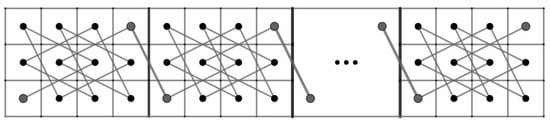

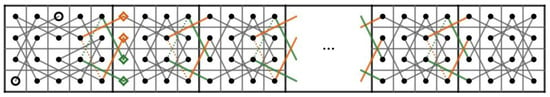

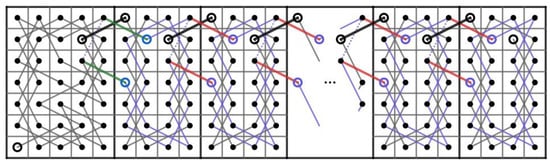

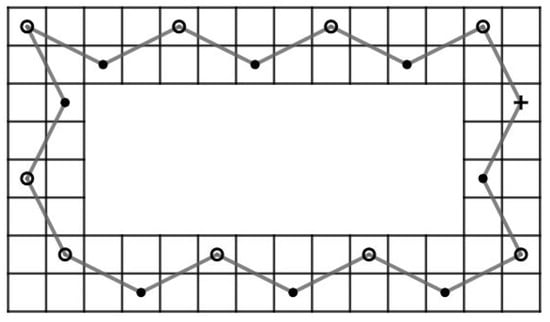

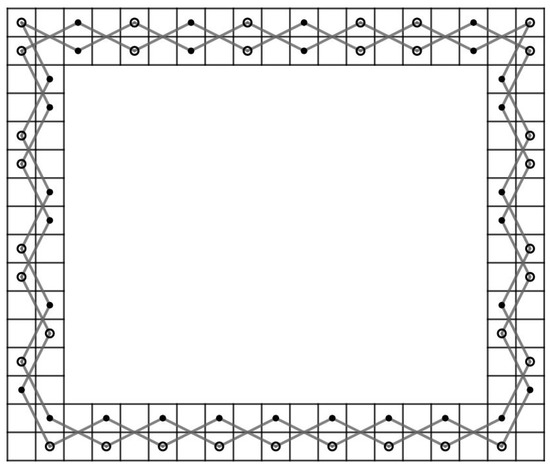

Case 1:.

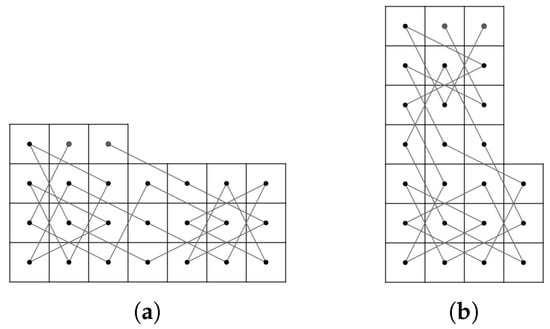

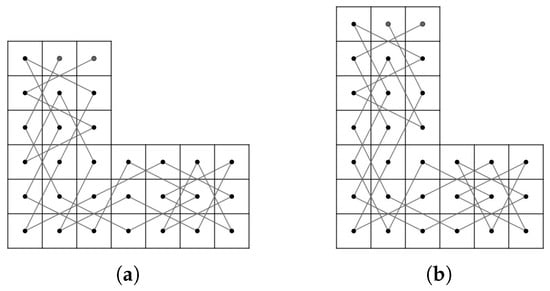

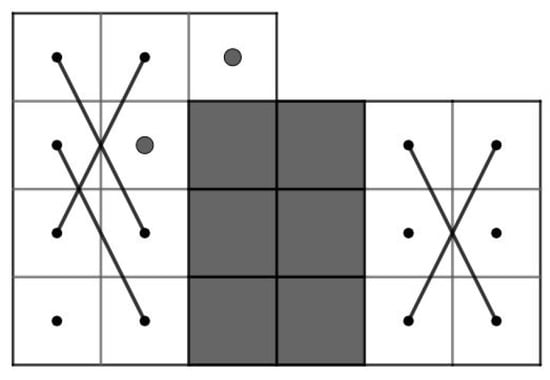

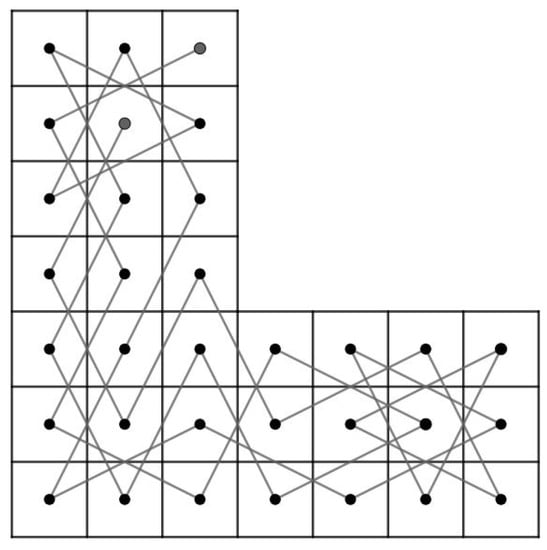

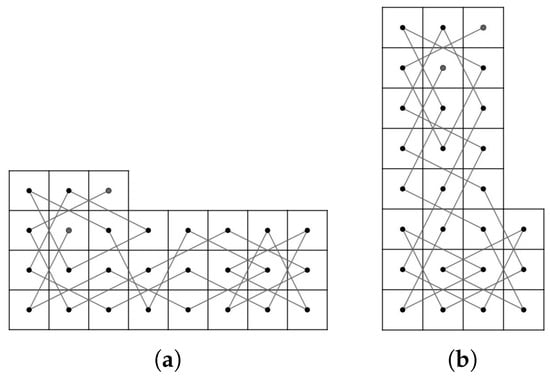

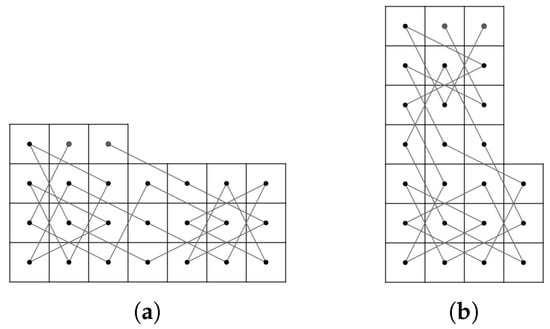

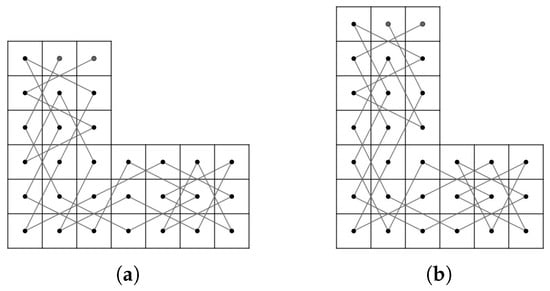

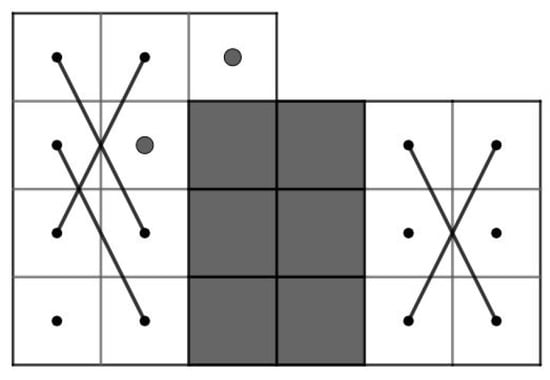

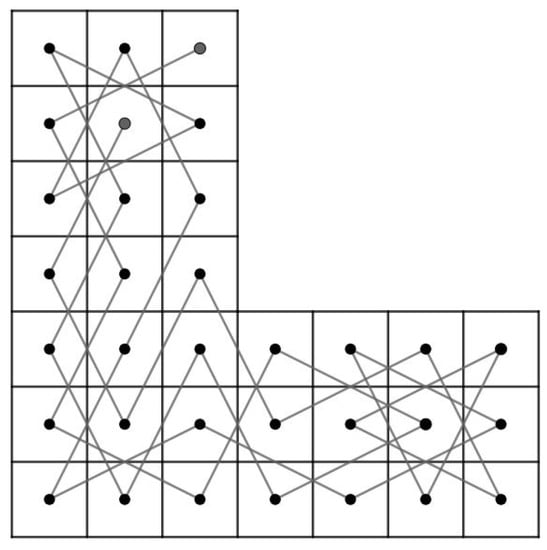

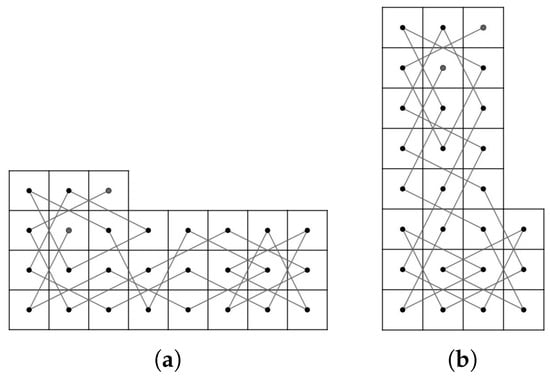

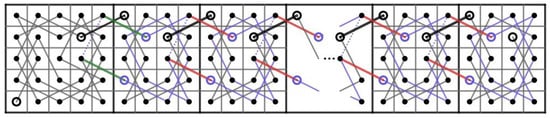

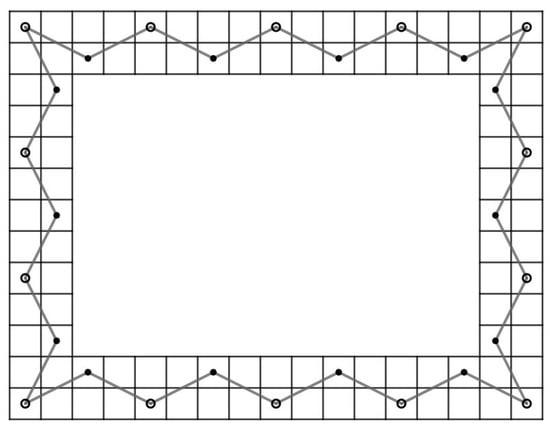

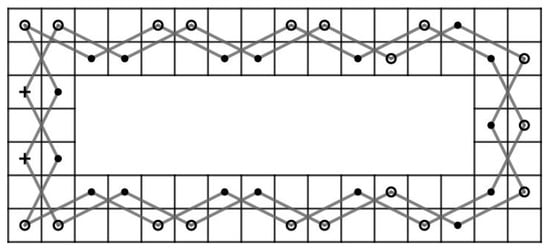

Case 1.1:m is odd and n is even, or m is even and n is odd. We partition the RB into LB and 7B, see Figure 71a for RB. Since is even and , by Theorem 5(b), the LB contains an OKT from to and by Corollary 2(b), the 7B contains an OKT from to . By joining and of LB to and of 7B, respectively, we obtain a CKT on RB as shown in Figure 71b for the RB.

Figure 71.

Two parts of RB and a CKT on RB.

Case 1.2:m and n are odd or even. We partition the RB into LB and 7B, see Figure 72a for RB. Since is odd and , by Theorem 5(a), the LB contains an OKT from to and by Corollary 2(a), the 7B contains an OKT from to . By joining and of LB to and of 7B, respectively, we obtain a CKT on RB as shown in Figure 72b for the RB.

Figure 72.

Two parts of RB and a CKT on RB.

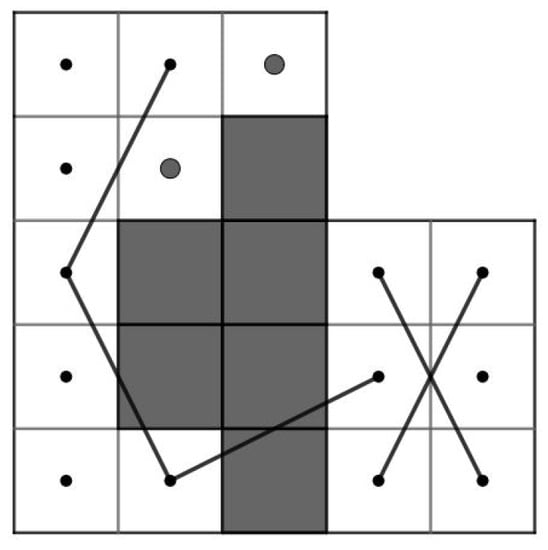

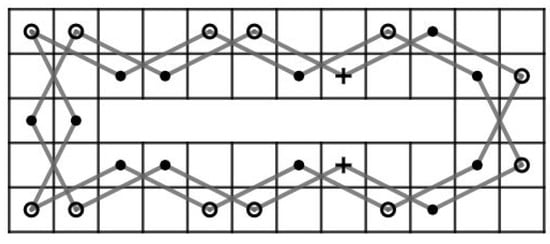

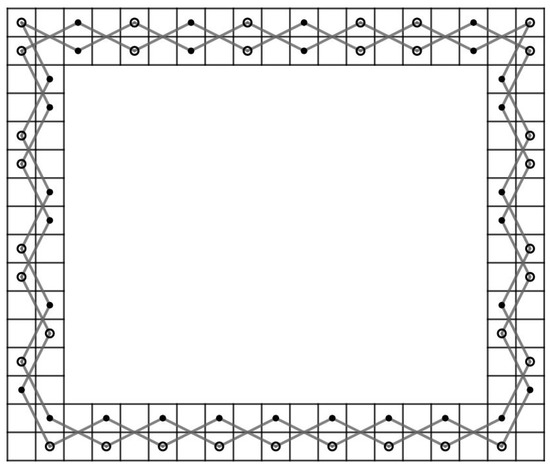

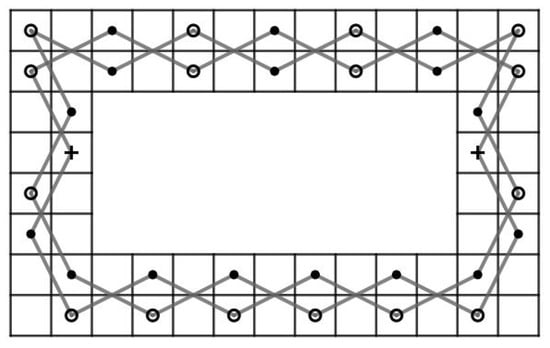

Case 2: for . We partition the RB into LB and 7B, see Figure 73a for RB. By Theorem 4 and Corollary 1, the LB has a CKT that contains an edge and 7B has a CKT that contains an edge . By deleting of LB and of 7B and joining and of LB to and of 7B, respectively, we obtain a CKT on RB, as show in Figure 73b for RB.

Figure 73.

Two parts of RB and a CKT on RB.

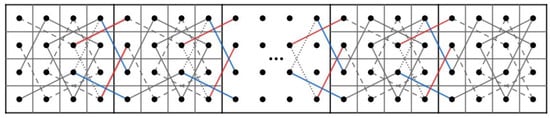

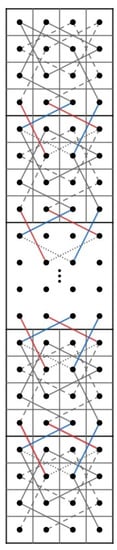

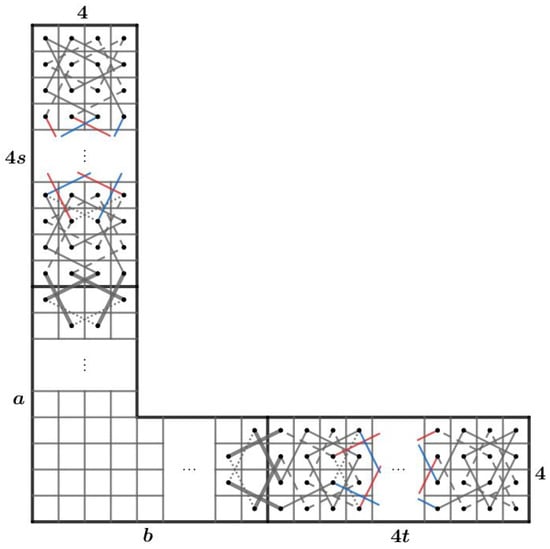

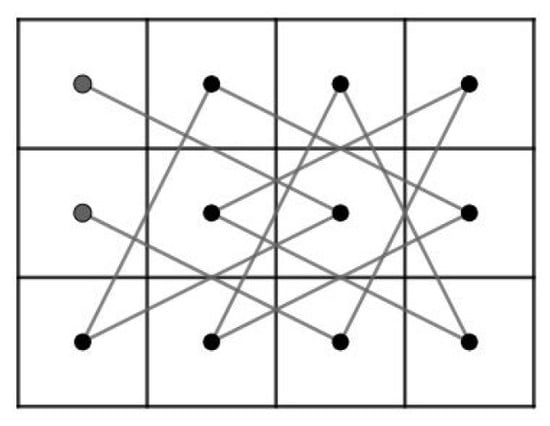

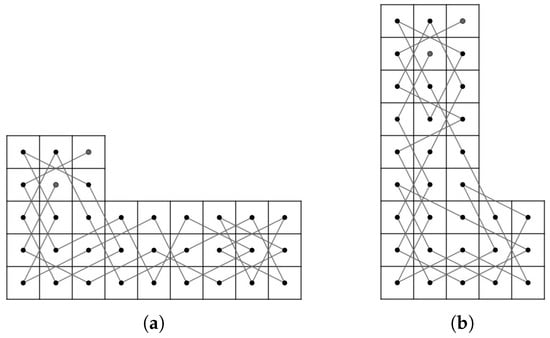

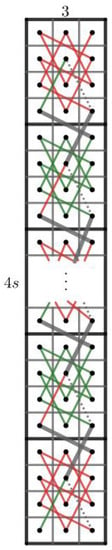

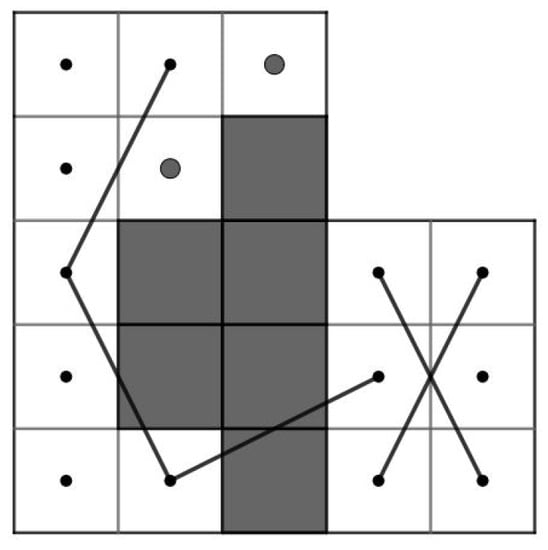

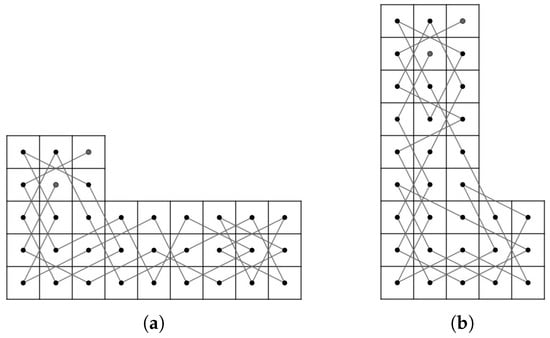

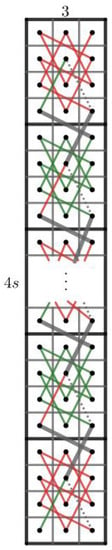

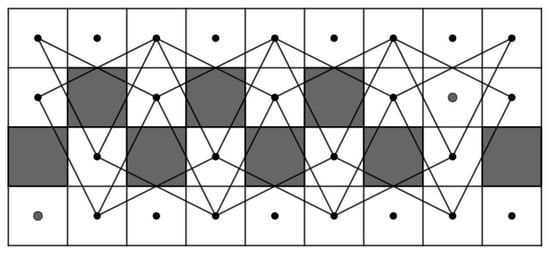

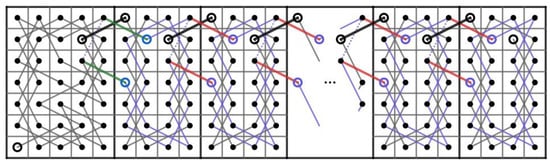

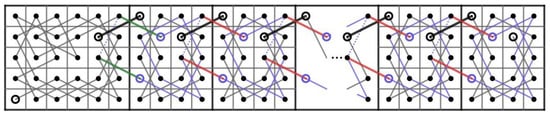

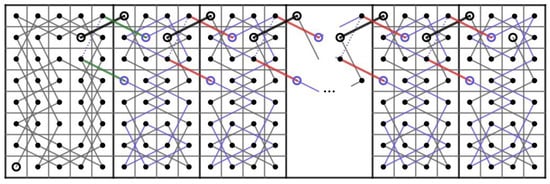

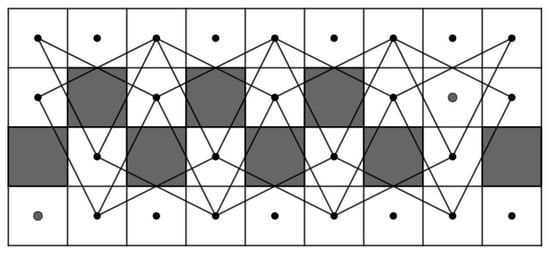

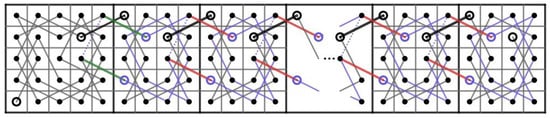

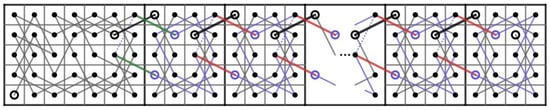

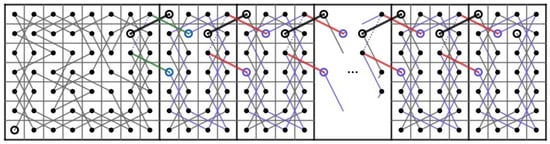

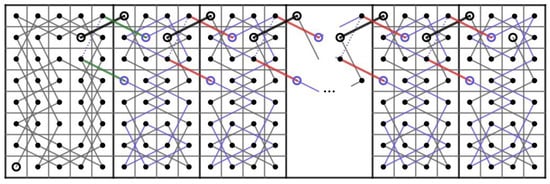

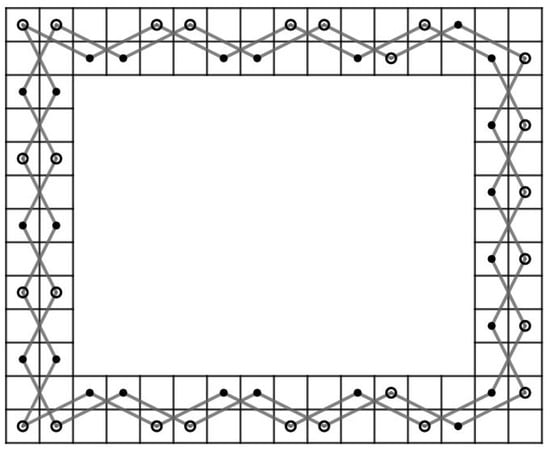

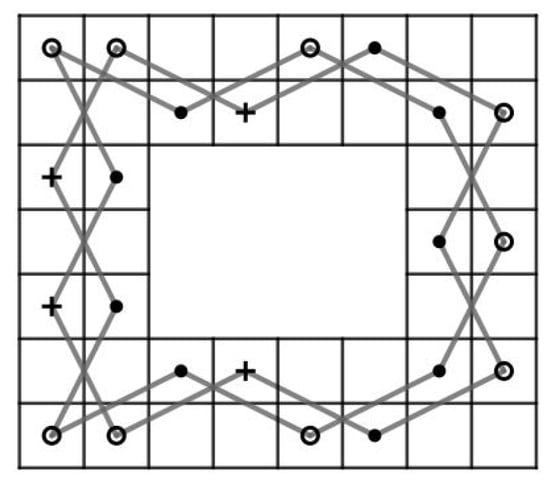

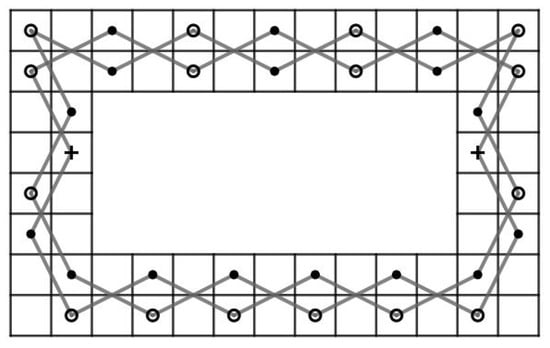

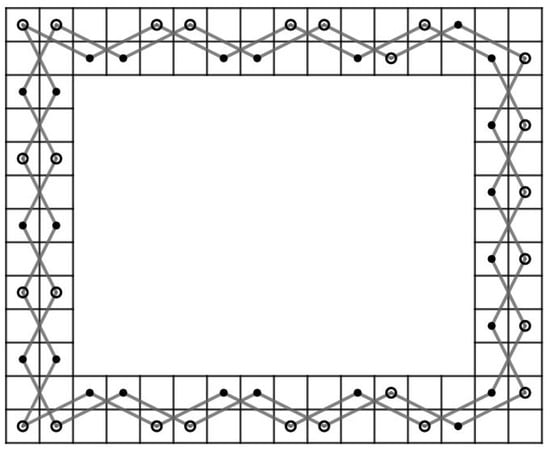

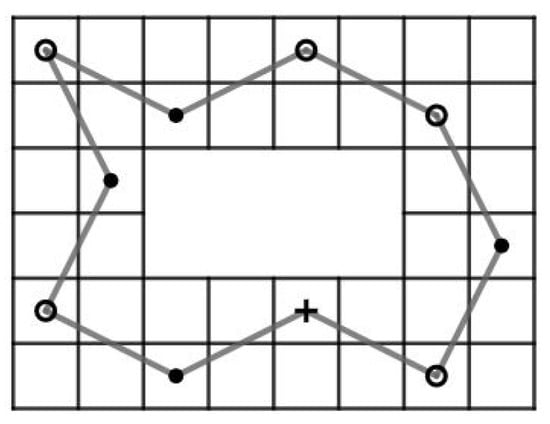

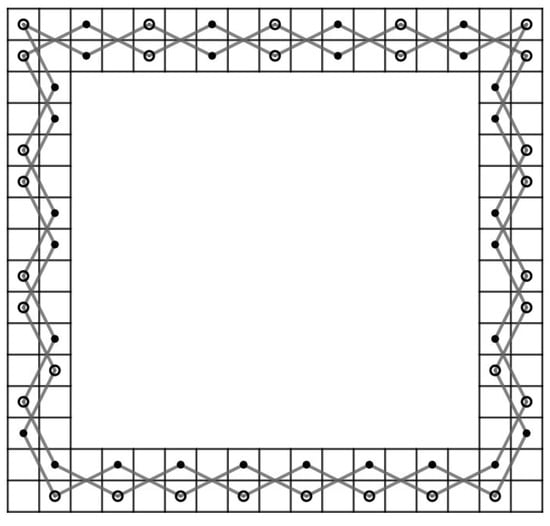

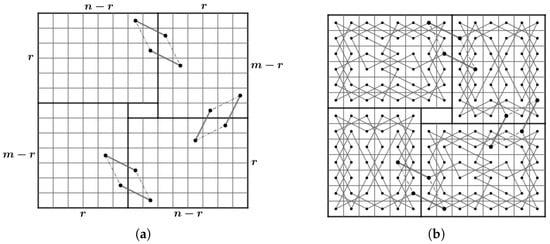

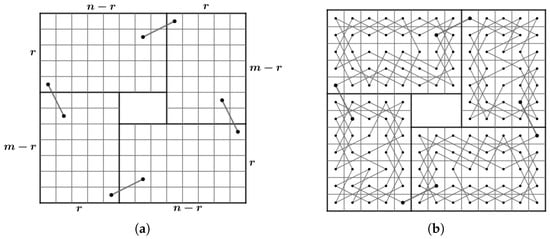

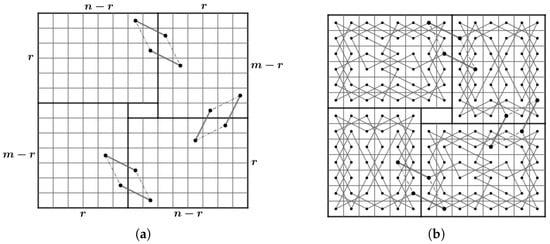

Case 3:.

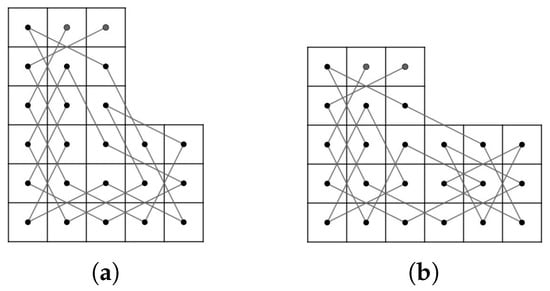

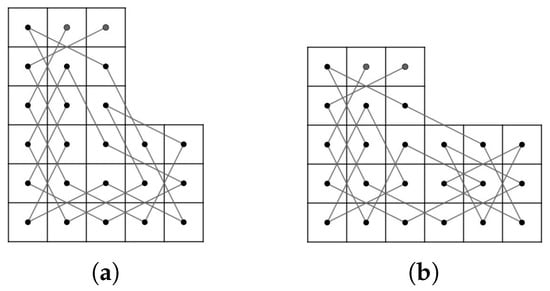

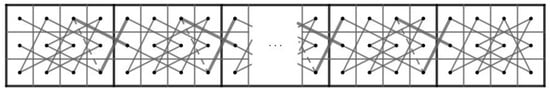

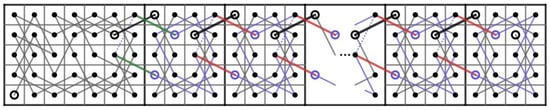

Case 3.1:r is even. We partition the RB into two CB() and two CB(), see Figure 74a for RB. There are three steps to obtain a CKT which has some edges on each partitioned board. First, we consider a CB(). By Theorem 1, it contains a CKT having edges and . Rotate CB() 90 degrees clockwise, we obtain a CKT on CB() of the upper right-hand side having edges and . Next, rotate CB() 90 degrees counterclockwise, we obtain a CKT on CB() of the lower left-hand side having edge . Finally, we consider a CB() on the upper left-hand side. By Theorem 1, it contains a CKT having edges and . Rotate CB() 180 degrees clockwise, we obtain a CKT on CB() of the lower right-hand side having edges and .

Figure 74.

Four parts of RB and a CKT on RB.

Thus, if we use the position on the RB, there are 4 CKT on each partition having six edges, namely , , , , and .

Next, to construct a CKT on RB, we delete these six edges and join these six edges: , , , , and instead, as shown in Figure 74b for RB.

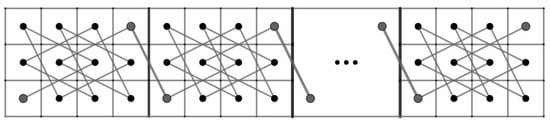

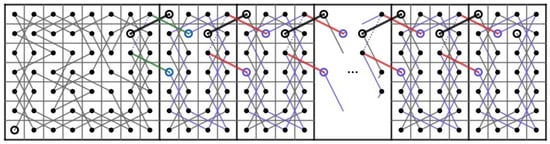

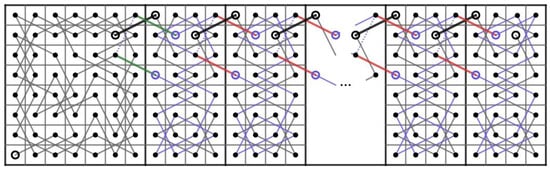

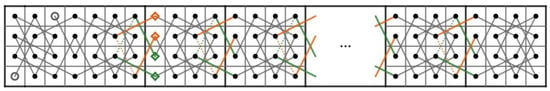

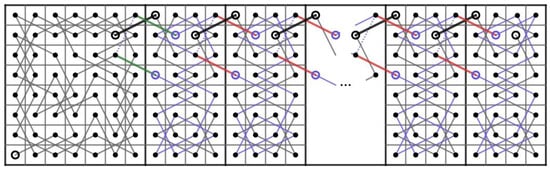

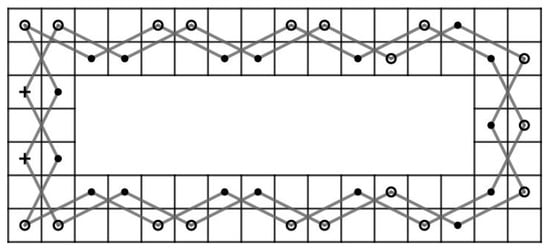

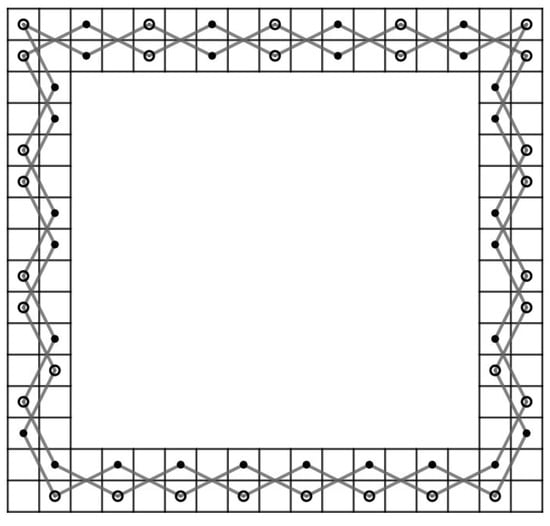

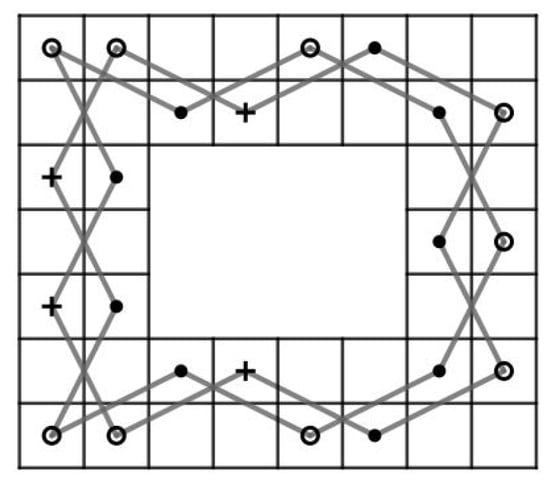

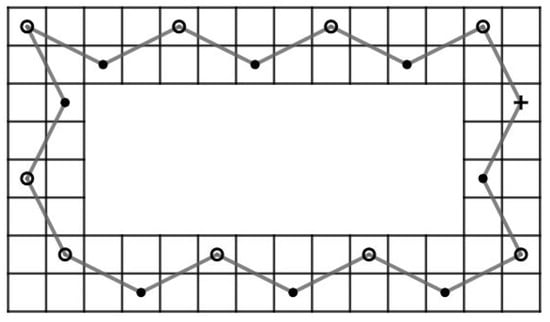

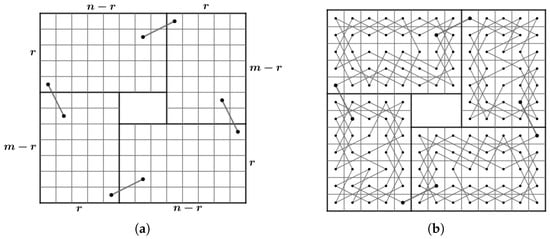

Case 3.2:r is odd. We partition the RB into two CB() and two CB(), see Figure 75a for RB. There are three steps to obtain an OKT having two end-points on each partitioned board. First, we consider a CB(). By Theorem 6(b), it contains an OKT from to . Rotate CB() 90 degrees clockwise, we obtain an OKT from to on CB() of the upper right-hand side. Next, rotate CB() 90 degrees counterclockwise, we obtain an OKT from to on CB() of the lower left-hand side. Finally, we consider a CB() on the upper left-hand side. By Theorem 6, it contains an OKT from to . Rotate CB() 180 degrees clockwise, we obtain an OKT from and on CB() of the lower right-hand side.

Figure 75.

Four parts of RB and a CKT on RB.

Thus, if we use the position on the RB, there are 4 OKTs on each partition having eight end vertices, namely , , , , , , and .

Next, to construct a CKT on the RB, we join four edges: , , and , as shown in Figure 75b for RB.

This completes the proof. □

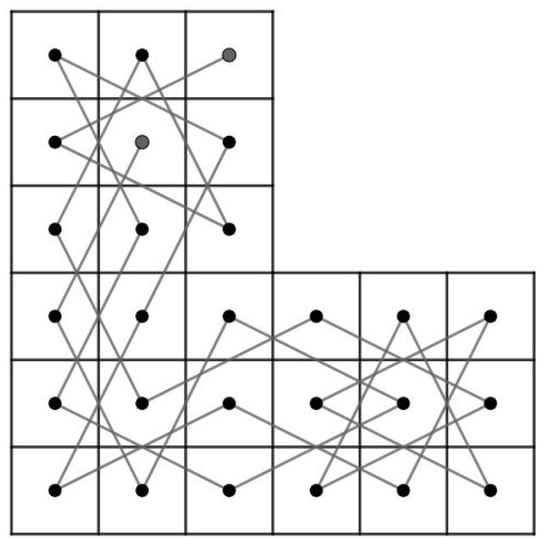

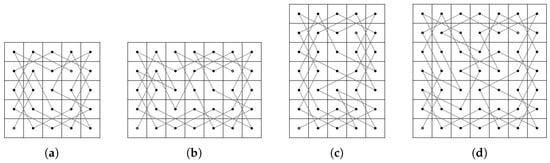

5. Conclusions and Discussion

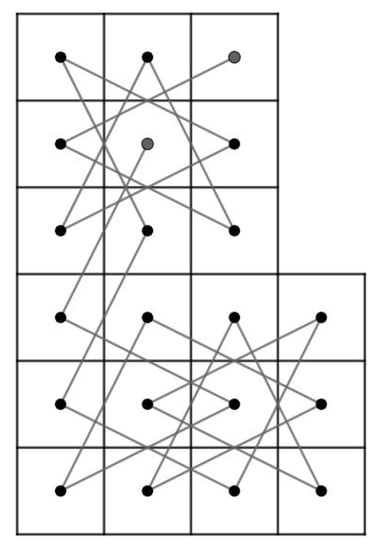

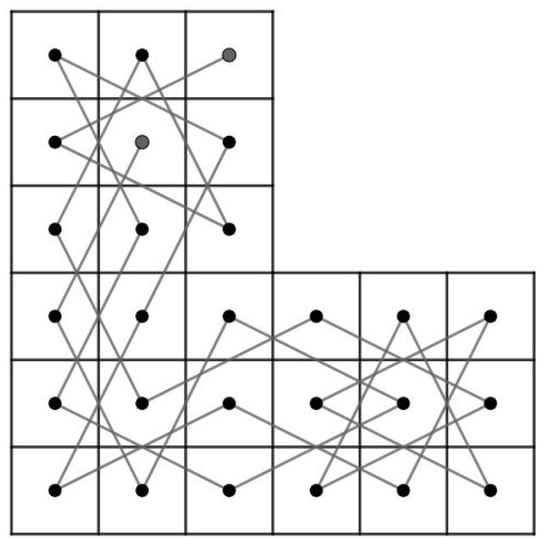

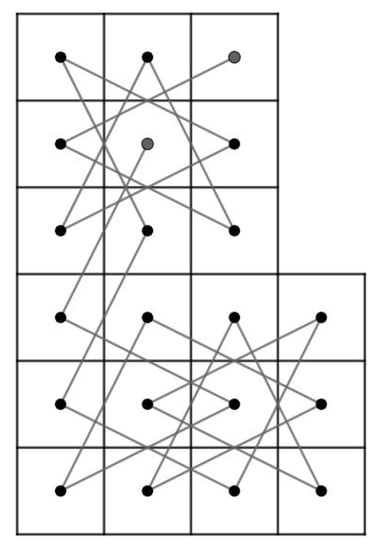

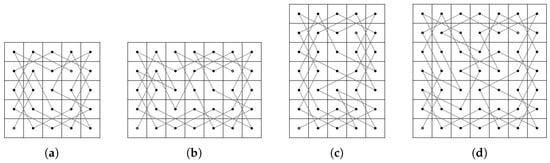

In this paper, we have obtained necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of a CKT for the RB. In every case of Theorem 8, it can be seen that the CKTs are constructed by smaller board-pieces that have diagonal or horizontal or vertical symmetries. As a consequence, to obtain our main result, we have to study the existence of a CKT on LB and LB. In the future, an interesting study is to find necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of a CKT for the general L-board, namely LB, which is the L-board consisting of m rows n with the lower leg of width l and the upper leg of width u, see Figure 76.

Figure 76.

LB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S., R.B. and S.S.; methodology, W.S., R.B. and S.S.; validation, W.S., R.B. and S.S.; formal analysis, W.S.; investigation, W.S.; resources, W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S.; writing—review and editing, R.B. and S.S.; visualization, W.S.; supervision, R.B. and S.S.; project administration, R.B. and S.S.; funding acquisition, W.S. and R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported financially by Research Assistantship Fund, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CKT | Closed Knight’s Tour |

| OKT | Open Knight’s Tour |

| CB | chessboard |

| LB | L-board of size |

| 7B | 7-board of size |

| RB | -ringboard |

References

- Cairns, G. Pillow chess. Math. Mag. 2002, 75, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaio, J. Which chessboards have a closed knight’s tour within the cube? Electron. J. Comb. 2007, 14, R32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaio, J.; Bindia, M. Which chessboards have a closed knight’s tour within the rectangular prism? Electron. J. Comb. 2011, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Watkins, J.J. Knight’s tours for cubes and boxes. Congr. Numer. 2006, 181, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, J.J. Knight’s tours on a torus. Math. Mag. 1997, 70, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.J. Knight’s tours on cylinders and other surfaces. Congr. Numer. 2000, 143, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Singhun, S.; Karudilok, K.; Boonklurb, R. Some Forbidden Rectangular Chessboards with Generalized Knight’s Moves. Thai J. Math. 2020, 133–145. Available online: http://thaijmath.in.cmu.ac.th/index.php/thaijmath/issue/archive (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Bai, S.; Huang, J. Generalized knight’s tour on 3D chessboards. Discret. Appl. Math. 2010, 158, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chia, G.L.; Ong, S.-H. Generalized Knight’s tours on rectangular chessboards. Discret. Appl. Math. 2005, 150, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, A.J. Which rectangular chessboards have a knight’s tour? Math. Mag. 1991, 64, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaio, J.; Hippchen, T. Closed Knight’s Tours with Minimal Square Removal for All Rectangular Boards. Math. Mag. 2009, 82, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullington, G.; Eroh, L.; Winters, S.J.; Johns, G.L. Knight’s tours on rectangular chessboards using external squares. J. Discret. Math. 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.M.; Farnsworth, D.L. Knight’s Tours on 3 × n Chessboards with a Single Square Removed. Open J. Discret. Math. 2013, 3, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bi, B.; Butler, S.; DeGraaf, S.; Doebel, E. Knight’s tours on boards with odd dimensions. Involve 2015, 8, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiitala, H.R. The knight’s tour problem on boards with holes. In Research Experiences for Undergraduates Proceedings; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 1996; pp. 132–151. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).