A Systematic Literature Review of the Design Approach and Usability Evaluation of the Pain Management Mobile Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Method

2.1. Research Questions

- RQ1:

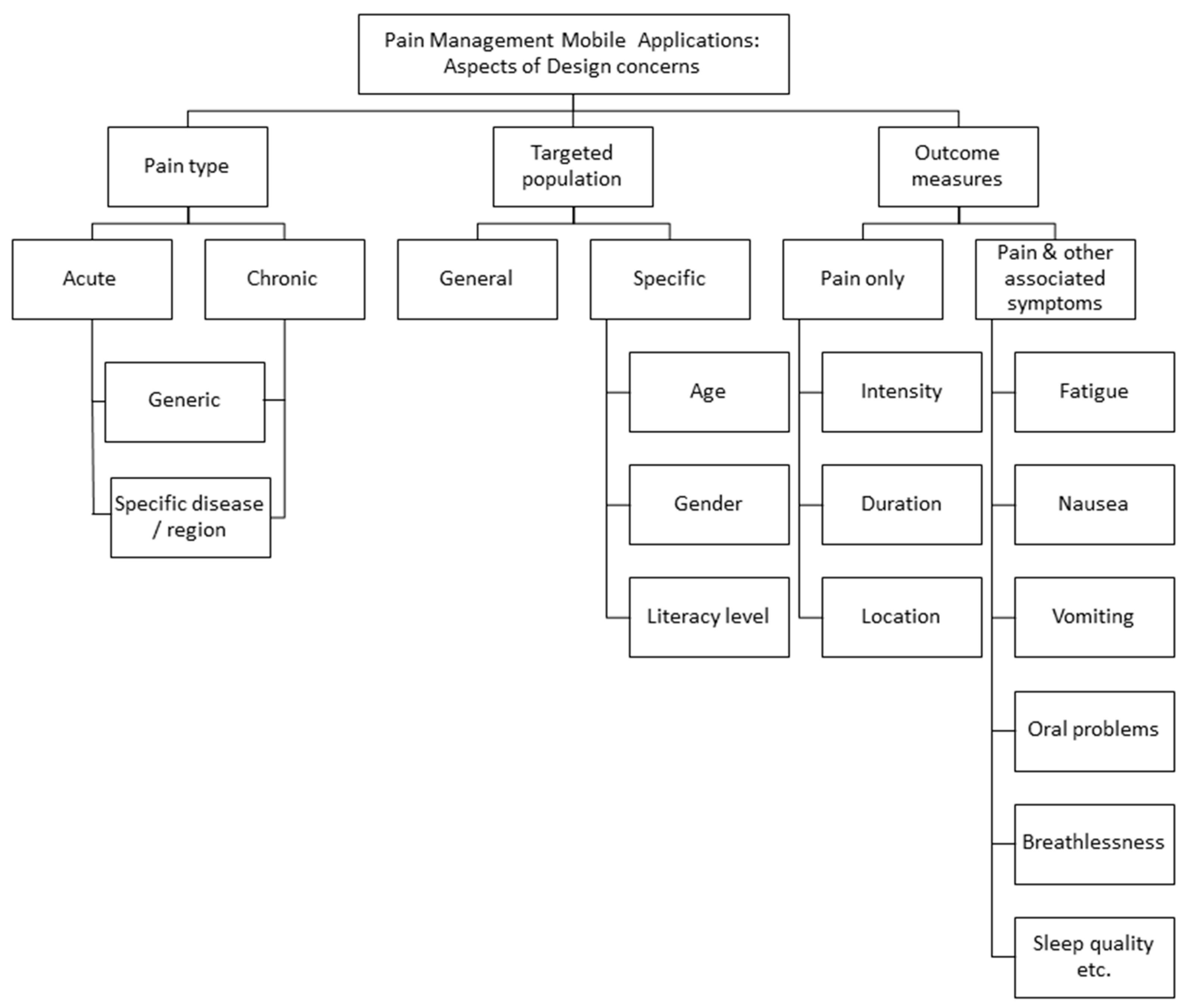

- What are the general characteristics of the pain management mobile apps with respect to pain type, targeted population, and outcome measures?

- RQ2:

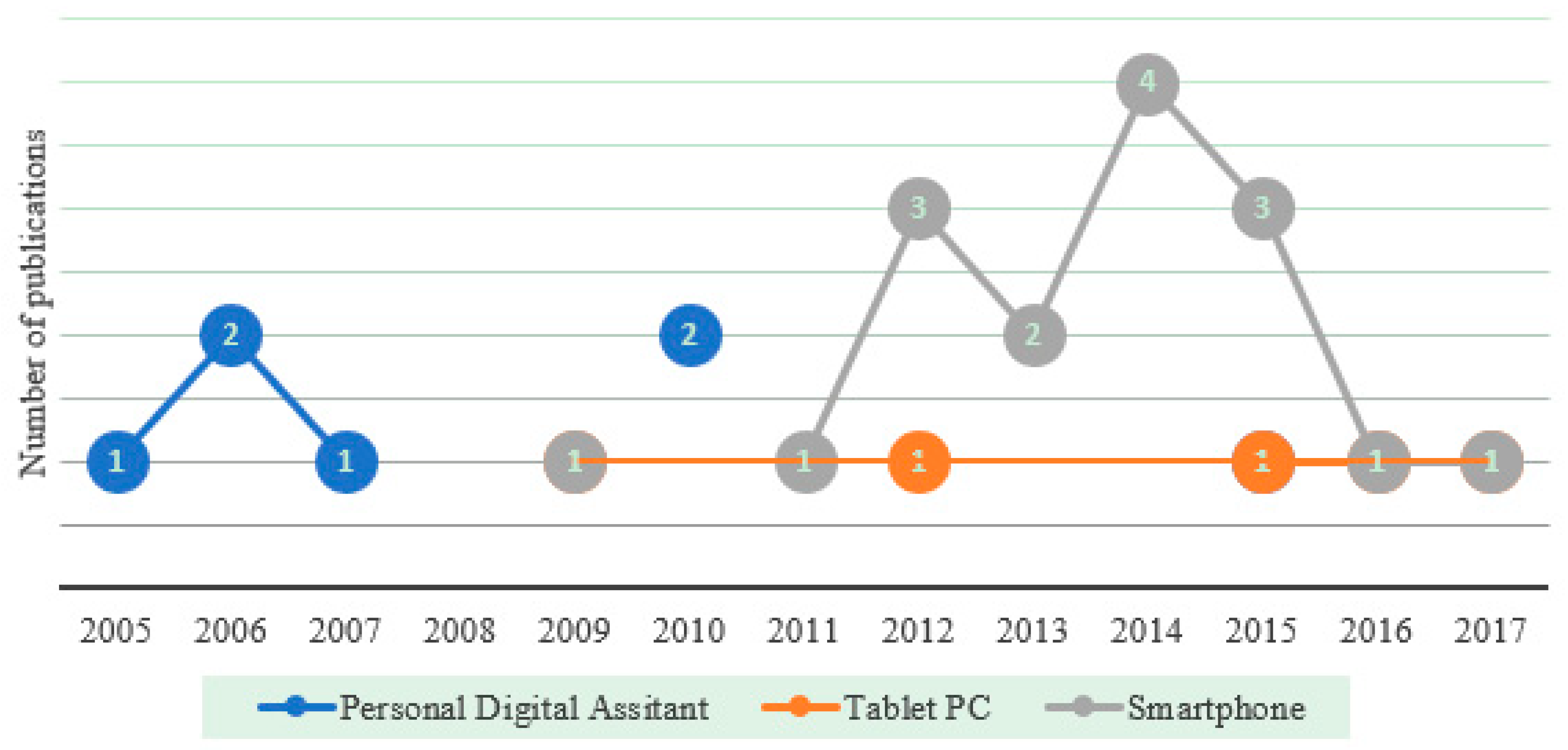

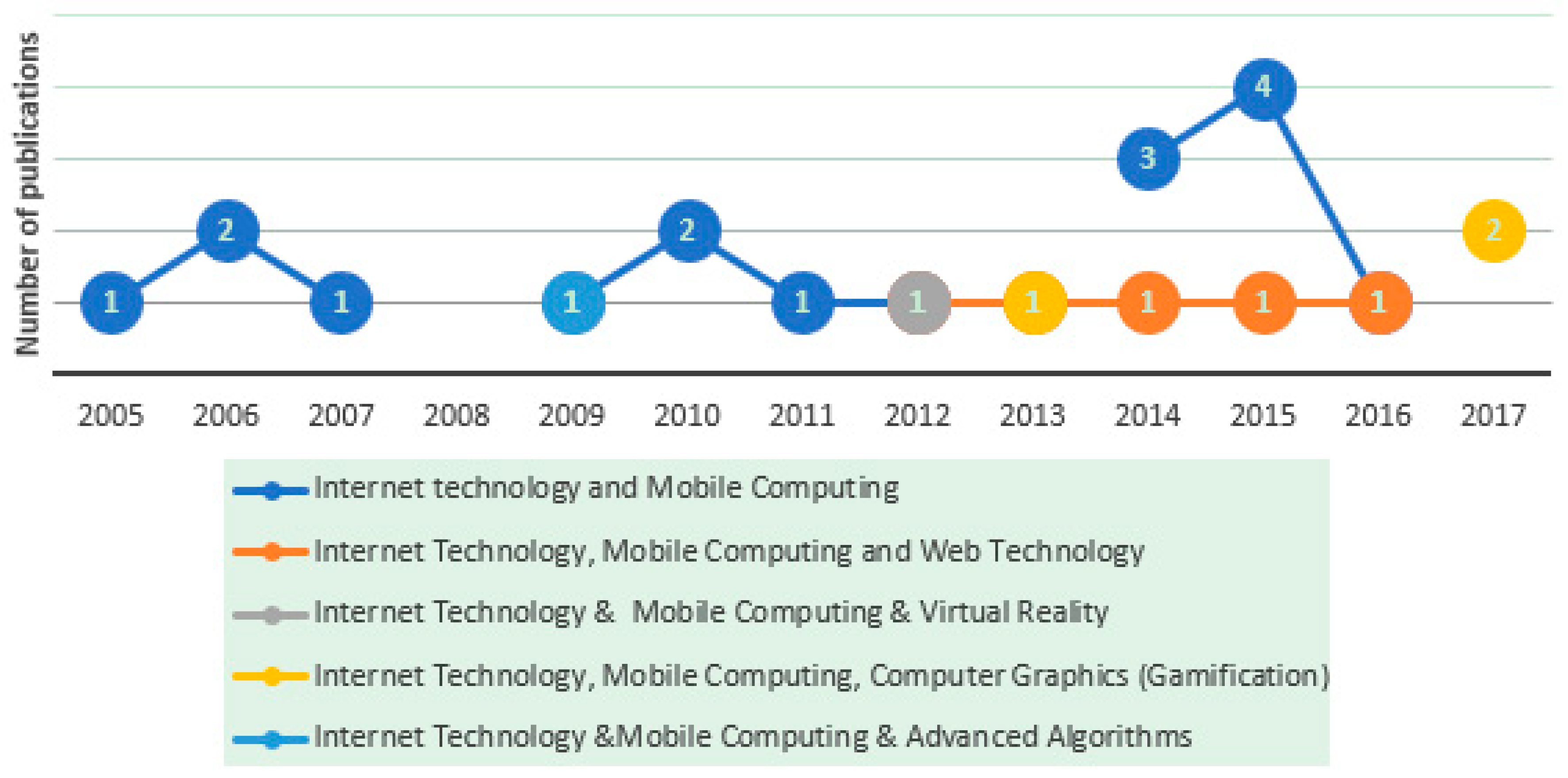

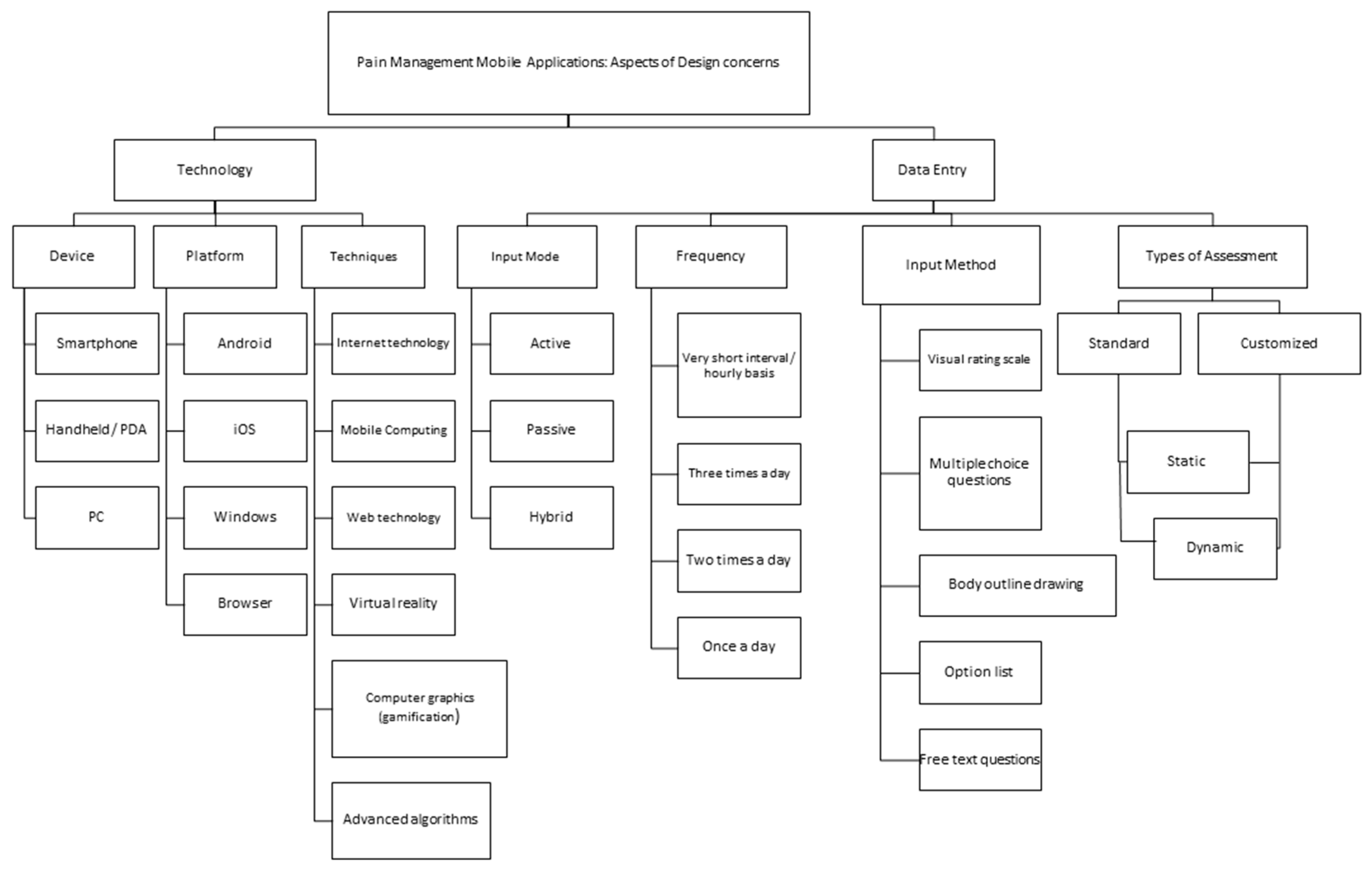

- What are the technologies adopted by the pain management mobile applications with respect to mobile devices, application platform, and techniques that are involved in the proposed solutions?

- RQ3:

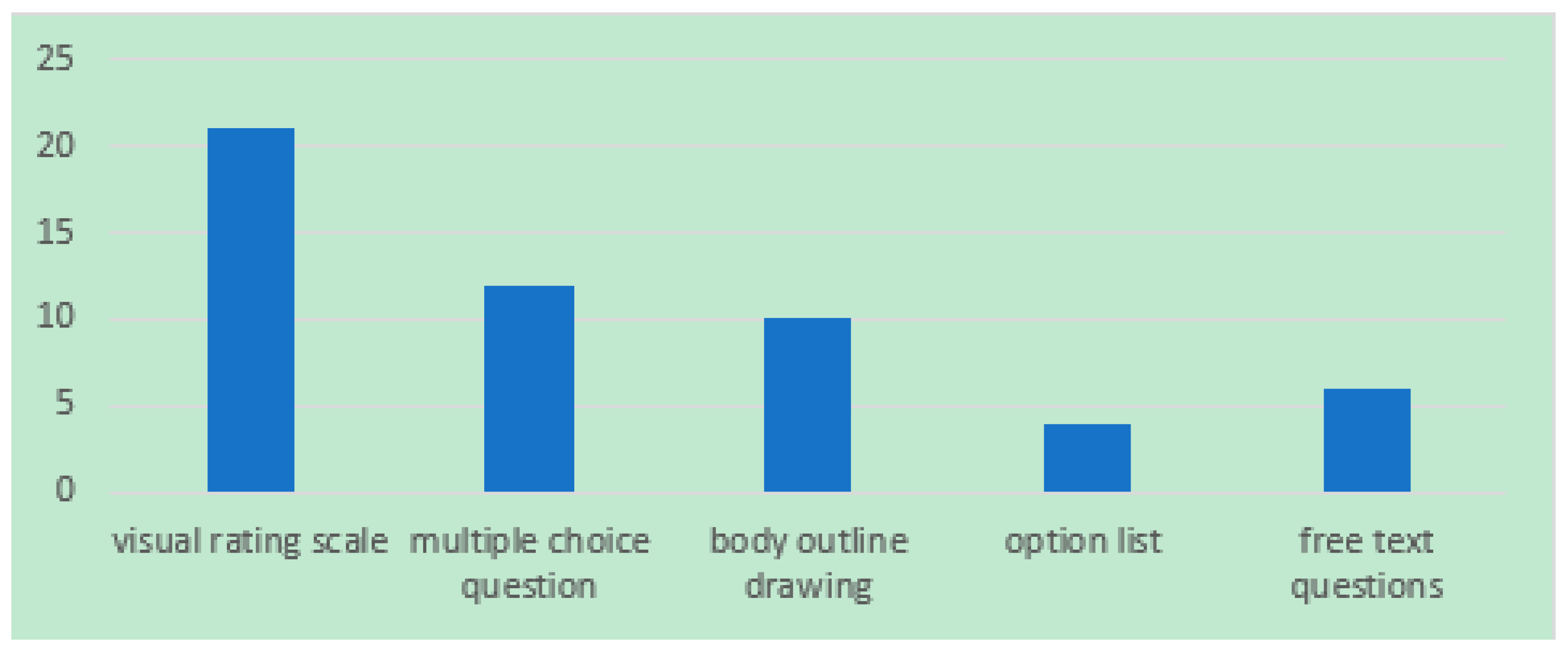

- What are the adopted approaches for data entry of pain management mobile applications?

- RQ3.1:

- What are the types of pain data assessment that are adopted?

- RQ3.2:

- What are the pain data input modes that are involved?

- RQ3.3:

- What are the pain data input methods that are used?

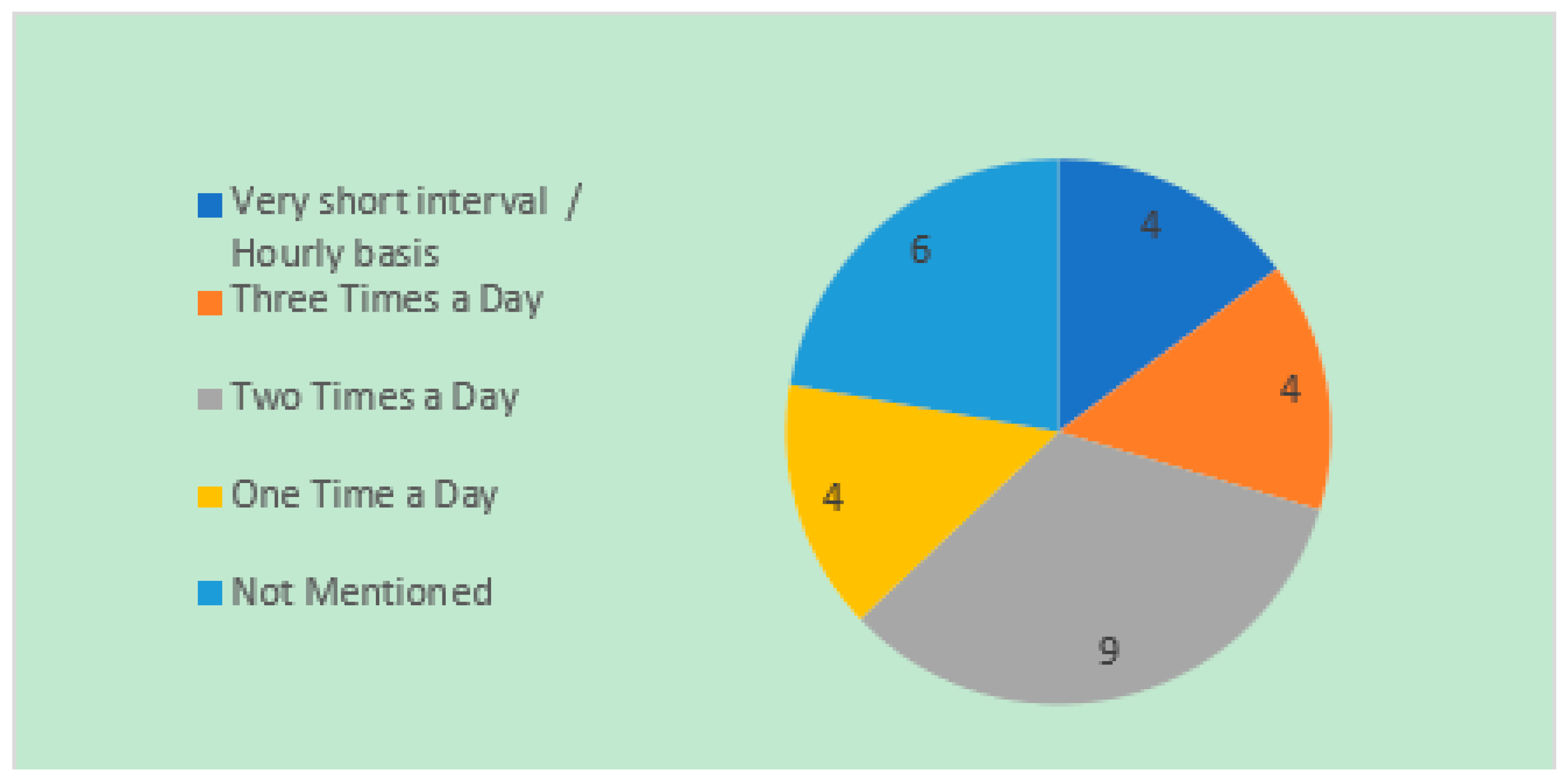

- RQ3.4:

- What is the optimal pain data input frequency?

- RQ4:

- What are the approaches to evaluate the usability of pain management mobile applications?

- RQ4.1:

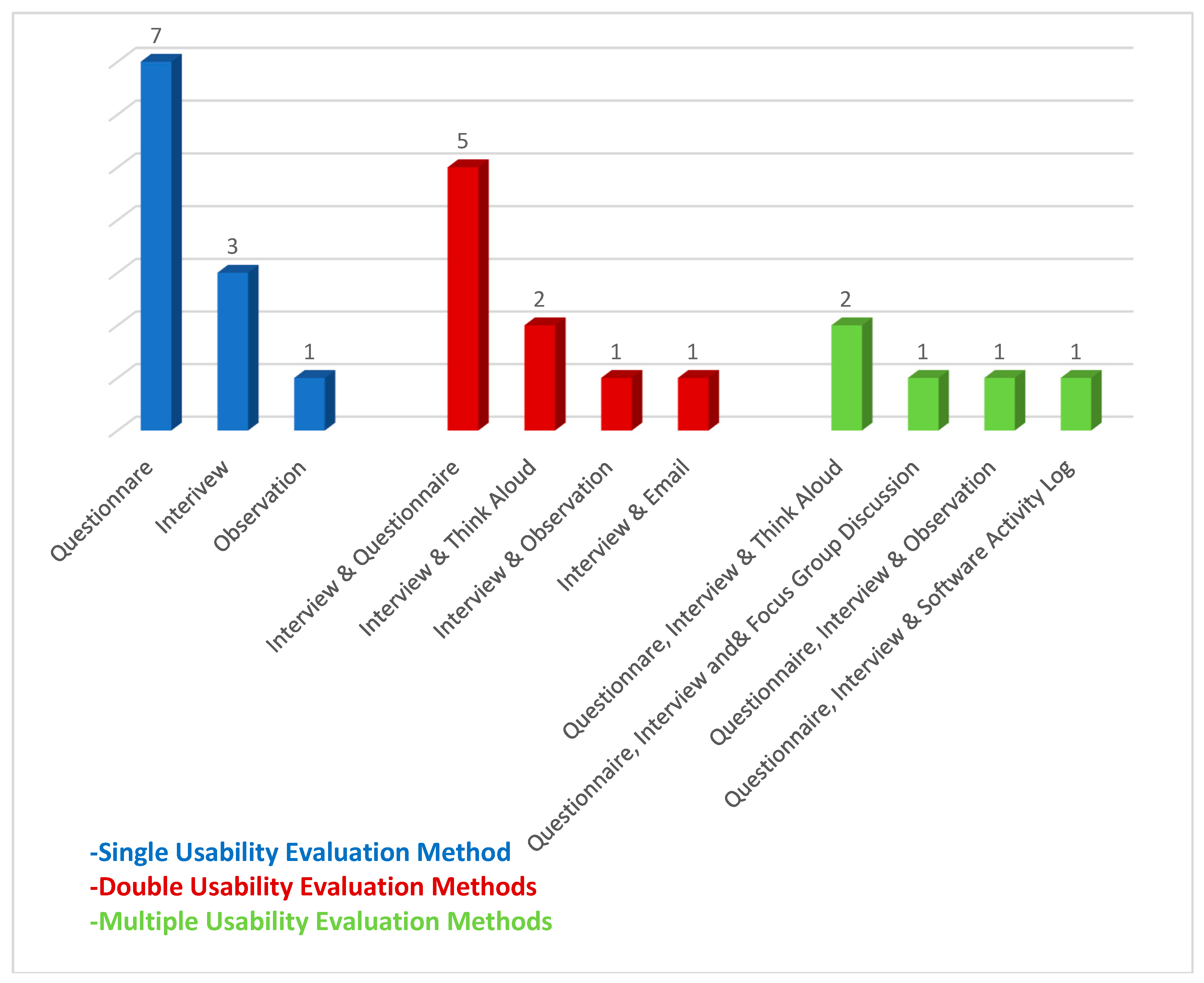

- What methods are used to evaluate the usability?

- RQ4.2:

- Which usability features are more targeted in the studies?

2.2. Search Strategy

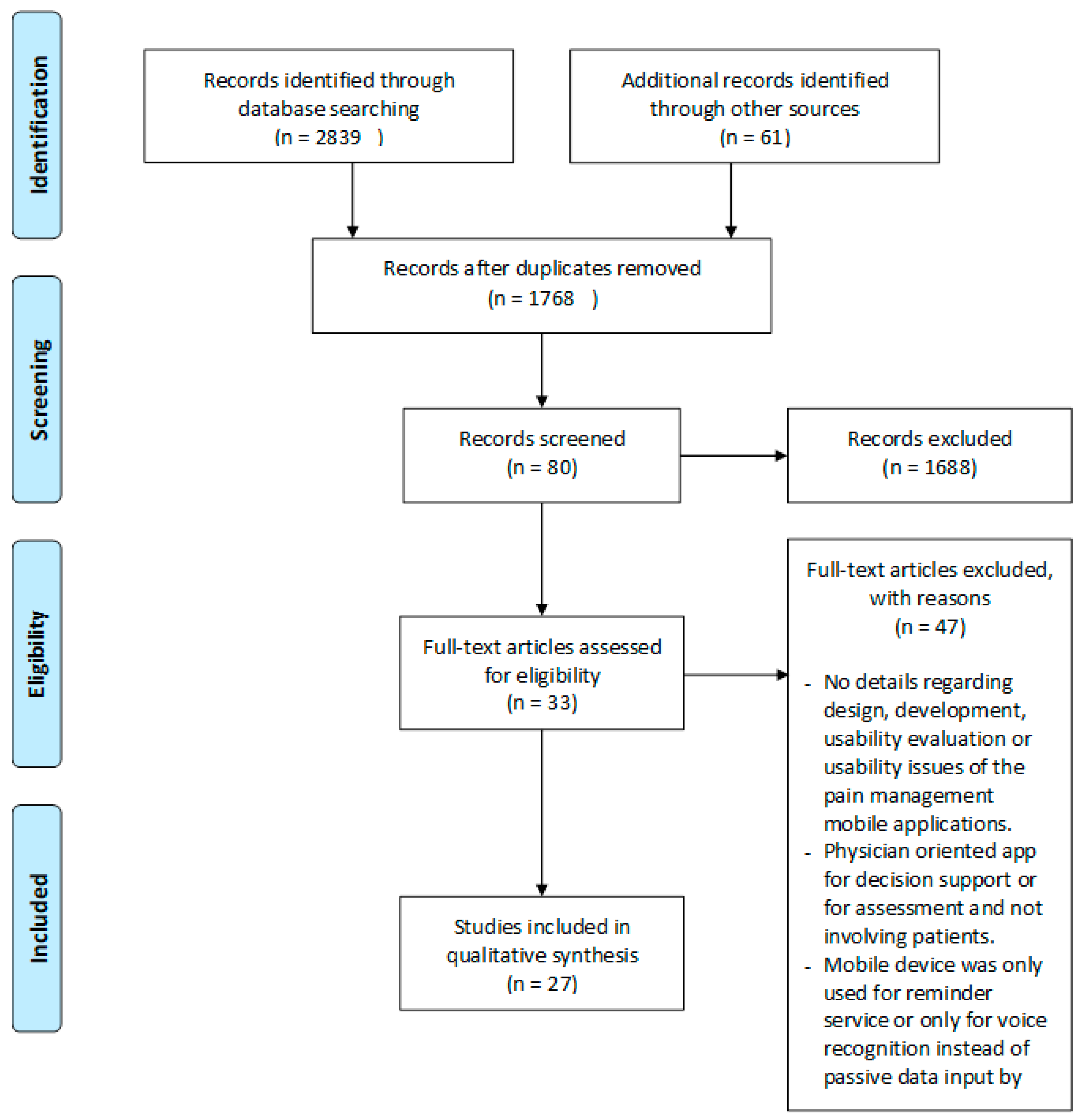

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Terms

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- The study must be a peer-reviewed publication.

- The study must be published within the timeframe of 2005 to 2017.

- The study must be in English.

- The study subject must be humans with no age limitation.

- The study must include details of the design and development of patient-oriented pain management mobile applications or systems.

- The study must involve a touchscreen portable handheld device such as a smartphone, Personal Digital Assistants (PDA), or tablet, etc.

- The study must involve manual entry or the partial automatic extraction of data by some sensor devices.

- The study must provide information on the usability evaluation method that was involved in that research.

- The study must provide results regarding user feedback on the application, and highlight the usability issues.

- If it does not fulfill the inclusion criteria.

- If the study is not focused on the design, development, and evaluation of the pain management mobile applications.

- If it is a review, commentary, or editorial paper.

- If it involves an ordinary cell phone for reminder services or for voice recognition only.

- If it involves a physician-oriented app for decision support or assessment.

2.6. Study Selection Procedure

2.7. Quality Assessment

2.8. Data Extraction

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview

- RQ1:

- What are the general characteristics of the pain management mobile apps with respect to pain type, targeted population, and outcome measures?

- RQ2:

- What are the technologies adopted by the pain management mobile applications with respect to the mobile devices, application platform, and techniques that are involved in the proposed solutions?

- RQ3:

- What are the adopted approaches for data entry of pain management mobile applications?

- RQ3.1:

- What are the types of pain data assessment adopted?

- RQ3.2:

- What are the pain data input modes involved?

- RQ3.3:

- What are the pain data input methods used?

- RQ3.4:

- What is the optimal pain data input frequency?

3.2. Finding: A Taxonomy of Design Concerns

3.3. Usability of Pain Management Mobile Applications

- RQ4:

- What are the approaches to evaluate the usability of pain management mobile applications?

- RQ4.1:

- What methods are used to evaluate usability?

- RQ4.2:

- Which usability features are more targeted in the studies?

3.4. Finding: Usability Issues and Solutions

3.5. Discussion: A Usability Matrix of Usability Issues

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arneric, S.P.; Laird, J.M.; Chappell, A.S.; Kennedy, J.D. Tailoring chronic pain treatments for the elderly: Are we prepared for the challenge? Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morone, N.E.; Weiner, D.K. Pain as the fifth vital sign: Exposing the vital need for pain education. Clin. Ther. 2013, 35, 1728–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereau, R.W.; Sluka, K.A.; Maixner, W.; Savage, S.R.; Price, T.J.; Murinson, B.B.; Sullivan, M.D.; Fillingim, R.B. A pain research agenda for the 21st century. J. Pain 2014, 15, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, P.A. Chronic Pain Management: The Essentials; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.Y.; Pisu, M.; Kvale, E.A.; Johns, S.A. Developing effective cancer pain education programs. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012, 16, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalloo, C.; Jibb, L.A.; Rivera, J.; Agarwal, A.; Stinson, J.N. “There’s a pain app for that”: Review of patient-targeted smartphone applications for pain management. Clin. J. Pain 2015, 31, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, J.C.; Joshi, G.P. Smartphone applications for chronic pain management: A critical appraisal. J. Pain Res. 2016, 9, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundararaman, L.V.; Edwards, R.R.; Ross, E.L.; Jamison, R.N. Integration of mobile health technology in the treatment of chronic pain: A critical review. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2017, 42, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceau, L.D.; Link, C.; Jamison, R.N.; Carolan, S. Electronic diaries as a tool to improve pain management: Is there any evidence? Pain Med. 2007, 8 (Suppl. 3), S101–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuna, Y.J.; Patterson, P.E. A suggestion for future research on interface design of an internet-based telemedicine system for the elderly. Work 2012, 41 (Suppl. 1), 353–356. [Google Scholar]

- Consulting, V.W. Mhealth for Development: The Opportunity of Mobile Technology for Healthcare in the Developing World; UN Foundation-Vodafone Foundation Partnership: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, A.C.; Stockdale, R.S.; Sharma, S. A strategic approach to m-health. Health Inf. J. 2009, 15, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Vega, R.; Miro, J. Mhealth: A strategic field without a solid scientific soul. A systematic review of pain-related apps. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portelli, P.; Eldred, C. A quality review of smartphone applications for the management of pain. Br. J. Pain 2016, 10, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoldson, C.; Stones, C.; Allsop, M.; Gardner, P.; Bennett, M.I.; Closs, S.J.; Jones, R.; Knapp, P. Assessing the quality and usability of smartphone apps for pain self-management. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, B.A.; McCullagh, P.; Davies, R.; Mountain, G.A.; McCracken, L.; Eccleston, C. Technology-mediated therapy for chronic pain management: The challenges of adapting behavior change interventions for delivery with pervasive communication technology. Telemed. J. e-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2011, 17, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.S.; Dhingra, L.K. A systematic review of smartphone applications for chronic pain available for download in the united states. J. Opioid Manag. 2014, 10, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayebi, F.; Desharnais, J.-M.; Abran, A. The State of the Art of Mobile Application Usability Evaluation; CCECE: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews; Keele University: Keele, UK, 2004; Volume 33, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mariano, D.C.; Leite, C.; Santos, L.H.; Rocha, R.E.; de Melo-Minardi, R.C. A guide to performing systematic literature reviews in bioinformatics. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1707.05813. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, N.; Araujo, P.; Viana, J.; da Costa, M.D. Evaluation of a ubiquitous and interoperable computerised system for remote monitoring of ambulatory post-operative pain: A randomised controlled trial. Technol. Health Care Off. J. Eur. Soc. Eng. Med. 2014, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ingadottir, B.; Blondal, K.; Thue, D.; Zoega, S.; Thylen, I.; Jaarsma, T. Development, usability, and efficacy of a serious game to help patients learn about pain management after surgery: An evaluation study. JMIR Serious Games 2017, 5, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anatchkova, M.D.; Saris-Baglama, R.N.; Kosinski, M.; Bjorner, J.B. Development and preliminary testing of a computerized adaptive assessment of chronic pain. J. Pain Off. J. Am. Pain Soc. 2009, 10, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckmann, R.; Vidal, A. Design of a handheld electronic pain, treatment and activity diary. J. Biomed. Inf. 2010, 43, S32–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, N.; Kidd, L.; Miller, M.; Sage, M.; Khorrami, J.; McGee, M.; Cassidy, J.; Niven, K.; Gray, P. Utilising handheld computers to monitor and support patients receiving chemotherapy: Results of a uk-based feasibility study. Supportive Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Supportive Care Cancer 2006, 14, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachizuka, M.; Yoshiuchi, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Iwase, S.; Nakagawa, K.; Kawagoe, K.; Akabayashi, A. Development of a personal digital assistant (pda) system to collect symptom information from home hospice patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2010, 13, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggott, C.; Gibson, F.; Coll, B.; Kletter, R.; Zeltzer, P.; Miaskowski, C. Initial evaluation of an electronic symptom diary for adolescents with cancer. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2012, 1, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, J.N.; Jibb, L.A.; Nguyen, C.; Nathan, P.C.; Maloney, A.M.; Dupuis, L.L.; Gerstle, J.T.; Alman, B.; Hopyan, S.; Strahlendorf, C.; et al. Development and testing of a multidimensional iphone pain assessment application for adolescents with cancer. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibb, L.A.; Stevens, B.J.; Nathan, P.C.; Seto, E.; Cafazzo, J.A.; Stinson, J.N. A smartphone-based pain management app for adolescents with cancer: Establishing system requirements and a pain care algorithm based on literature review, interviews, and consensus. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2014, 3, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, R.; Ream, E.; Richardson, A.; Connaghan, J.; Johnston, B.; Kotronoulas, G.; Pedersen, V.; McPhelim, J.; Pattison, N.; Smith, A.; et al. Development of a novel remote patient monitoring system: The advanced symptom management system for radiotherapy to improve the symptom experience of patients with lung cancer receiving radiotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 2015, 38, E37–E47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, M.A.; Chung, W.W.; Martinez, A.; Gago-Masague, S.; Sender, L. Pain buddy: A novel use of m-health in the management of children’s cancer pain. Comput. Biol. Med. 2016, 76, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstenbach, L.M.; Zwakhalen, S.M.; Courtens, A.M.; van Kleef, M.; de Witte, L.P. Feasibility of a mobile and web-based intervention to support self-management in outpatients with cancer pain. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 23, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibb, L.A.; Cafazzo, J.A.; Nathan, P.C.; Seto, E.; Stevens, B.J.; Nguyen, C.; Stinson, J.N. Development of a mhealth real-time pain self-management app for adolescents with cancer: An iterative usability testing study. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 34, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, C.B.; Schatz, J.C.; Puffer, E.; Sanchez, C.E.; Stancil, M.T.; Roberts, C.W. Use of handheld wireless technology for a home-based sickle cell pain management protocol. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, E.; Stinson, J.; Duran, J.; Gupta, A.; Gerla, M.; Ann Lewis, M.; Zeltzer, L. Usability testing of a smartphone for accessing a web-based e-diary for self-monitoring of pain and symptoms in sickle cell disease. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2012, 34, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demiris, G. The diffusion of virtual communities in health care: Concepts and challenges. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 62, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, N.; Stinson, J.N.; Ross, D.; Lukombo, I.; Mittal, N.; Joshi, S.V.; Belfer, I.; Krishnamurti, L. Development, content validity, and user review of a web-based multidimensional pain diary for adolescent and young adults with sickle cell disease. Clin. J. Pain 2015, 31, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serif, T.; Ghinea, G. Recording of time-varying back-pain data: A wireless solution. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2005, 9, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blodt, S.; Pach, D.; Roll, S.; Witt, C.M. Effectiveness of app-based relaxation for patients with chronic low back pain (relaxback) and chronic neck pain (relaxneck): Study protocol for two randomized pragmatic trials. Trials 2014, 15, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorbi, M.J.; Mak, S.B.; Houtveen, J.H.; Kleiboer, A.M.; van Doornen, L.J. Mobile web-based monitoring and coaching: Feasibility in chronic migraine. J. Med. Internet Res. 2007, 9, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguet, A.; McGrath, P.J.; Wheaton, M.; Mackinnon, S.P.; Rozario, S.; Tougas, M.E.; Stinson, J.N.; MacLean, C. Testing the feasibility and psychometric properties of a mobile diary (mywhi) in adolescents and young adults with headaches. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015, 3, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nes, A.A.; Eide, H.; Kristjansdottir, O.B.; van Dulmen, S. Web-based, self-management enhancing interventions with e-diaries and personalized feedback for persons with chronic illness: A tale of three studies. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 93, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Palacios, A.; Herrero, R.; Belmonte, M.A.; Castilla, D.; Guixeres, J.; Molinari, G.; Baños, R.M.; Botella, C. Ecological momentary assessment for chronic pain in fibromyalgia using a smartphone: A randomized crossover study. Eur. J. Pain 2014, 18, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, J.N.; Petroz, G.C.; Tait, G.; Feldman, B.M.; Streiner, D.; McGrath, P.J.; Stevens, B.J. E-ouch: Usability testing of an electronic chronic pain diary for adolescents with arthritis. Clin. J. Pain 2006, 22, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, E.; Kinnunen, T. Applying user-centered design to mobile application development. Commun. ACM 2005, 48, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Searle, G.; Nischelwitzer, A. On some Aspects of improving mobile applications for the elderly. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction, Beijing, China, 22–27 July 2007; Springer: Berlin, Germany; pp. 923–932. [Google Scholar]

- Spyridonis, F.; Gronli, T.-M.; Hansen, J.; Ghinea, G. Evaluating the usability of a virtual reality-based android application in managing the pain experience of wheelchair users. In Proceedings of the 2012 Annual International Conference of the Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), San Diego, CA, USA, 28 August–1 September 2012; pp. 2460–2463. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhu, Q.; Holroyd, K.A.; Seng, E.K. Status and trends of mobile-health applications for ios devices: A developer’s perspective. J. Syst. Softw. 2011, 84, 2022–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.E.; Reid, M.C. The promises and pitfalls of leveraging mobile health technology for pain care. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, R.; Brodbeck, D.; Degen, M.; Luthiger, J.; Wyss, R.; Reichlin, S. Persuasiveness of a mobile lifestyle coaching application using social facilitation. In Persuasive Technology; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.; Park, D.; Lee, H.E. Cognitive factors of using health apps: Systematic analysis of relationships among health consciousness, health information orientation, ehealth literacy, and health app use efficacy. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.; Cajamarca, G.; Herskovic, V.; Fuentes, C.; Campos, M. Helping elderly users report pain levels: A study of user experience with mobile and wearable interfaces. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2017, 2017, 9302328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.J.; Jessel, S.; Richardson, J.E.; Reid, M.C. Older adults are mobile too! Identifying the barriers and facilitators to older adults’ use of mhealth for pain management. BMC Geriatr. 2013, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.L.; Chaparro, B.S. Smartphone text input method performance, usability, and preference with younger and older adults. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, I.S.; Tanaka-Ishii, K. Text Entry Systems: Mobility, Accessibility, Universality; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.M.; Humphrey, L.; Kitchen, H.; Rehman, T.; Norquist, J.M. A qualitative study to develop a patient-reported outcome for dysmenorrhea. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2015, 24, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassaint, C.R.; Shah, N.; Jonassaint, J.; De Castro, L. Usability and feasibility of an mhealth intervention for monitoring and managing pain symptoms in sickle cell disease: The sickle cell disease mobile application to record symptoms via technology (smart). Hemoglobin 2015, 39, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. Usability inspection methods. In Proceedings of the Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 24–28 April 1994; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 377–378. [Google Scholar]

- Abras, C.; Maloney-Krichmar, D.; Preece, J. User-centered design. In Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction; Bainbridge, W., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; Volume 37, pp. 445–456. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 9241-11: Ergonomic Requirements for Office Work with Visual Display Terminals (vdts); The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; Volume 45.

- International Organization for Standardization; International Electrotechnical Commission. Software Engineering—Product Quality: Quality Model; ISO/IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Internacional de Normalización. ISO-IEC 25010: 2011 Systems and Software Engineering-Systems and Software Quality Requirements and Evaluation (Square)-System and Software Quality Models; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, H.; Kheir, O. The relationship between accessibility and usability of websites. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 28 April–3 May 2007; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Billi, M.; Burzagli, L.; Catarci, T.; Santucci, G.; Bertini, E.; Gabbanini, F.; Palchetti, E. A unified methodology for the evaluation of accessibility and usability of mobile applications. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2010, 9, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Searle, G.; Wernbacher, M. The effect of previous exposure to technology on acceptance and its importance in usability and accessibility engineering. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2011, 10, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition; Constellation: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| No | Quality Assessment Criteria | Ordinal Response Scale | Grades Acquired by the Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| QA1 | Relevancy of research design within the context of the study. | 0 (No)/0.5 (Partially)/1 (Yes) | 26 studies, 98% |

| QA2 | Clearly defined aims and objectives of the study. | 0 (No)/0.5 (Partially)/1 (Yes) | 26 studies, 98% |

| QA3 | Clearly stated findings and limitations of the study. | 0 (No)/0.5 (Partially)/1 (Yes) | 25 studies, 94% |

| QA4 | Valuable contribution of the study, based on the findings. | <20% (No)/20–80% (Partially)/>80% (Yes) | 23 studies, 85% |

| Pain Types | Acute Pain | Chronic Pain |

|---|---|---|

| General pain | - | 3 |

| Cancer pain | - | 9 |

| Sickle cell pain | - | 4 |

| Back pain | - | 2 |

| Musculoskeletal pain | - | 1 |

| Headache or migraine | - | 2 |

| Fibromyalgia pain | - | 1 |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | - | 1 |

| Dysmenorrhea pelvic pain | - | 1 |

| Neck pain | - | 1 |

| Postoperative pain | 2 | - |

| Characteristics | Definitions | Terminologies Used in the Studies for Usability Evaluations |

|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | “Accuracy and completeness with which users achieve specified goals” [61] | error prevention, usefulness, self-care behavior and symptom management, monitoring and managing symptoms, support of behavioral training key targets |

| Efficiency | “Resources expended in relation to the accuracy and completeness with which users achieve goals” [61] | completion time |

| Satisfaction | “Freedom from discomfort and positive attitudes toward the use of the product” [61] | usefulness, willingness to complete the survey again, self-efficacy, likability, acceptability, feedback |

| Appropriateness recognizability/ Understandability | “Degree to which users can recognize whether a product or system is appropriate for their needs” [63] | clarity of content, ease to understand, helpfulness of the tool in understanding the impact of pain, simplicity of the content, clarification of the wording of questions, readability, language, understanding, paraphrasing, comprehension (meaning and understanding of the question), completeness, comprehensiveness of the queries and response set, knowledge |

| User interface aesthetics/Attractiveness | “Degree to which a user interface enables a pleasing and satisfying interaction for the user” [63] | font size, color scheme, visual appearance and layout, inconsistency, aesthetics |

| Operability | “Degree to which a product or system is easy to operate, control, and appropriate to use” [63] | Navigation, ease of data input, ease of use, User-friendliness, the difficulty of completing the assessment, the responsiveness of the screens to touch, navigation, functionalities (submit, clear, cursor movement), user interaction, navigation of the site, issues with the interface, complexity, knowledge, communication and support, feedback |

| Learnability | “Degree to which a product or system enables the user to learn how to use it with effectiveness, efficiency in emergency situations” [63] | memory retrieval (ability to accurately recall the answer), complexity, workload demand |

| User error protection | “Degree to which a product or system protects users against making errors” [63] | system protection against making errors, error prevention |

| Accessibility | “Degree to which a product or system can be used by people with the widest range of characteristics and capabilities to achieve a specified goal in a specified context of use” [63] | the color scheme for the color blind, accessibility |

| Usability Issues | Solutions/Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The difficulty with the interpretation of the report or confusing reports [24,42]. | Additional reports were added along with the functionality of viewing web-based report and export diary data. It was also recommended to provide comprehensive reports to be viewed within the mobile application rather than be externally viewed [42]. |

| 2 | Confusion in understanding the terminology or wording [30,34,39,42,45,57]. | The wordings of questions were simplified and in the user manual; definitions of certain words/terminologies were also provided [42,45]. It was also suggested that the wording of the system’s questions and management instructions should be appropriate for the targeted population [30,34,57]. |

| 3 | Buttons not working properly [34]. | The “clickable” surface area corresponding to the app buttons and cursors was increased [34]. |

| 4 | Items with overlapping concepts [34,57]. | Keywords were made bold and underlined so that adolescents could easily distinguish the meaning of pain assessment questions [34]. Diary items were refined based on the feedback to remove the overlapping concepts [57]. |

| 5 | Slow responsiveness of the application [34,42]. | In order to expedite the process of data input and increase the efficiency of the application, some measures were taken, such as an addition of auto text or default values, alphabetically sorting the response set, and the provision of the most frequently entered options at the top of list. Moreover, data will be stored locally to overcome the issue and synchronized with the server simultaneously [42]. |

| 6 | Patients were forced to complete the entire sequence of questions, irrespective of whether they were not having any pain, as patients didn’t move the slider to the “No Pain” anchor [45]. | The addition of help features at various stages of data input to prevent users from errors e.g. reminding patients to move the slider to the end of the VAS if they are experiencing no pain [45]. |

| 7 | A few participants missed inputting the medications used, as they did not know the generic names [45]. | Changes were made to the diary by putting the brands as well as the generic names of medications [45]. |

| 8 | Difficult to locate and identify the triggers due to the complex hierarchal presentation and too many options to choose from [42]. | Relocation of the feature to make it accessible. The question was set to appear on the top of the screen while scrolling down to keep the question in mind during searching. Most of the repeated triggers were listed down in the list of the most frequently used triggers [42]. |

| 9 | Problem with retrospective entries e.g., past midnight entry without starting a new day or day-long constant pain entry [42]. | Removed the restriction on creating a diary entry if one already existed [42]. |

| 10 | Difficulty in diary entry due to a few inapplicable symptoms for constant pain [42]. | Option to skip or remove the unusable items was provided [42]. |

| 11 | Difficulties in setting the start and end time of pain as wake or sleep time [42]. | Default items were set for daily items [42]. |

| 12 | Difficulty in learning to use the application [39,42]. | Provision of instruction slides on the first launch of the application to explain its working and the addition of help buttons in various modules [42]. In [44], the feature of audio-recorded instructions was also incorporated to increase the accessibility for a wider number of people, e.g., elderly people or people with any visual impairment. |

| 13 | Failed to review all of the response options due to unseen or a not prominent enough prompt to scroll down for more responses [25]. | All of the response options for a query were presented on one screen to avoid the need for scrolling [25]. |

| 14 | Application very cumbersome to use [34,38,48] | Navigation was streamlined to minimize the steps to move from one module to the other [34], or the redistribution of items was done to shorten the length of the pain diary [38]. A second response loop was also designed, i.e,. if the answer of a question is marked “yes”, then the diary will proceed to ask the next relevant question for elaboration; otherwise, those nested questions will be skipped [38]. |

| 15 | Difficulty in handling visual analog scale, the slider was too sensitive and tricky to use [45] | The slider was transformed to be thicker on the VAS so that it would move more easily. In some inputs, the slider was replaced by the radio buttons to make the input easier [45]. |

| 16 | Problem in using stylus-based input, i.e., inputting number with stylus or selection from word descriptor list [24,25,39,45]. | Some space was added for entering new pain word descriptors. Also, word descriptors were arranged in alphabetical order, and the scroll bar was moved away from the word descriptors for clarity [45]. |

| 17 | The difficulty with number selection boxes where the tapping of the arrow is required for selection [25] | Replaced the number selection box with a pop-up number pad [25]. |

| 18 | Missing ‘‘back” button to return to the earlier screens to revise answers [25] | Back button was added to review the answers before submission [25]. |

| 19 | Frequent crashing/Software malfunction [23,34,58] | The application was reprogrammed and tested internally to resolve the malfunctioning [34]. |

| 20 | Difficulty in selecting an area on the body image [38] and not enough spots to highlight the problem area on the body diagram [45]. | Zoom function in the body diagram was provided for visual clarity [38]. In [39], it was also suggested to provide 3D visualization. In [45], the presentation location of some of the joints was improved. Also, labeled images of the body diagram were added in the instruction manual. Moreover, navigation assistance indicators were provided to move the body diagram left or right. |

| 21 | Less effectiveness and safety of a standalone system without active input of the healthcare professional [30]. | It was suggested in [39] that the applications should be connected with the central healthcare systems. The active input of a clinical expert could improve the effectiveness and safety of the system. In that case, a threshold level should be incorporated into the system to trigger an email alert to a registered nurse. The nurse will then contact the adolescent to assist in clinical decision making. Moreover, the threshold level could be established for the system to receive additional advice from the healthcare professional, if no improvement in pain condition is observed [30]. There must be a time-out feature in the system, in case of seeking advice from the healthcare professionals, to communicate with their care providers or other medical aid [30,39]. |

| 22 | Lack of acknowledgment for the patient [30,39]. | An alert system is also necessary to acknowledge the patient upon successful transmission of pain data to the central system [30,39]. |

| 23 | Over alerting or repeated notification [41,58]. | No specific solution recommended |

| 24 | Confusing pop-up screen messages [24]. | No specific solution recommended |

| 25 | Difficult to control the slider while scrolling down the screen [24]. | No specific solution recommended |

| 26 | Too small font size [39] | No specific solution recommended |

| 27 | Color scheme not suitable for color blinds [39]. | No specific solution recommended |

| ISO 9241-11 IS0/IEC 25010 | Effectiveness | Efficiency | Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriateness recognizability | A few participants missed inputting the medications used, as they did not know the generic names [45]. Less effectiveness and safety of a standalone system without the active input of the healthcare professional. [30] Lack of acknowledgment to the patient [30,39]. | The difficulty with the interpretation of the report [24]. | Confusing pop-up screen messages [24]. Confusion in understanding the terminology or wording [30,34,39,45,57]. Items with overlapping concepts [34,57]. Over alerting or repeated notification [41,58]. |

| Learnability | - | Difficulty in learning to use the application [39]. | |

| Operability | - | Difficult to control the slider while scrolling down the screen [24,25]. Application very cumbersome to use [31,48]. Difficulty in handling visual analog scale, the slider was too sensitive, and tricky to use [38,45]. Problem in using stylus-based input i.e., inputting number with stylus or selection from word descriptor list [24,25,39,45]. The difficulty with number selection boxes where tapping of the arrow is required for selection [25]. Missing ‘‘back” button to return to the earlier screens to revise answers [25]. Buttons not working properly [34]. Slow responsiveness of the application [34,42]. Difficult to locate and identify the triggers due to the complex hierarchal presentation and too many options from which to choose [42]. Problem with retrospective entries e.g., past midnight entry without starting a new day or day-long constant pain entry [42]. Difficulty in diary entry due to a few inapplicable symptoms for a constant pain [42]. Difficulties in setting start and end time of pain as wake or sleep time [42]. Failed to review all of the response options due to an unseen or not prominent prompt to scroll down for more responses [25]. Difficulty in selecting an area on the body image [38] and not enough spots to highlight the problem area on the body diagram [45]. | - |

| User Error Protection | - | - | Frequent crashing/software malfunction [23,34,58]. Patients were forced to complete the entire sequence of questions, irrespective of the fact they were not having any pain, as patients didn’t move the slider to the “No Pain” anchor [45]. |

| User Interface Aesthetics | - | - | Too small font size [39]. |

| Accessibility | 1. Color scheme not suitable for color blinds [39] | - | - |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shah, U.e.M.; Chiew, T.K. A Systematic Literature Review of the Design Approach and Usability Evaluation of the Pain Management Mobile Applications. Symmetry 2019, 11, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11030400

Shah UeM, Chiew TK. A Systematic Literature Review of the Design Approach and Usability Evaluation of the Pain Management Mobile Applications. Symmetry. 2019; 11(3):400. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11030400

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Umm e Mariya, and Thiam Kian Chiew. 2019. "A Systematic Literature Review of the Design Approach and Usability Evaluation of the Pain Management Mobile Applications" Symmetry 11, no. 3: 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11030400

APA StyleShah, U. e. M., & Chiew, T. K. (2019). A Systematic Literature Review of the Design Approach and Usability Evaluation of the Pain Management Mobile Applications. Symmetry, 11(3), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11030400