Antecedents of Symmetry in Physicians’ Prescription Behavior: Evidence from SEM-Based Multivariate Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Significance and Objectives of the Study

3. Academics Relevance

4. Previous Literature and Conceptual Framework

The Physicians’ Prescription Behavior Definition

5. Pharmaceutical Medical and Marketing Tools

Medical Literature & Journal Advertising

6. Scientific Activities

7. Medical Representatives’ Effectiveness

8. Promotional Material (Samples & Gifts)

9. Personal Obligations

10. The Effect of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising (DTCA)

11. Moderating Influence: Corporate Image and Customer Relationship

Corporate Image

12. Customer Relationship

13. Material and Methods

13.1. Estimation Techniques

13.2. Data Collection and Respondents’ Profile

14. Data Analysis and Results Estimations

15. Descriptive Statistics of Initial Constructs

16. Reliabilities and AVE Analysis

17. Exploratory Factor Analysis—EFA

18. Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Techniques

19. Total Variance Explained

20. The Anti-Image Matrix

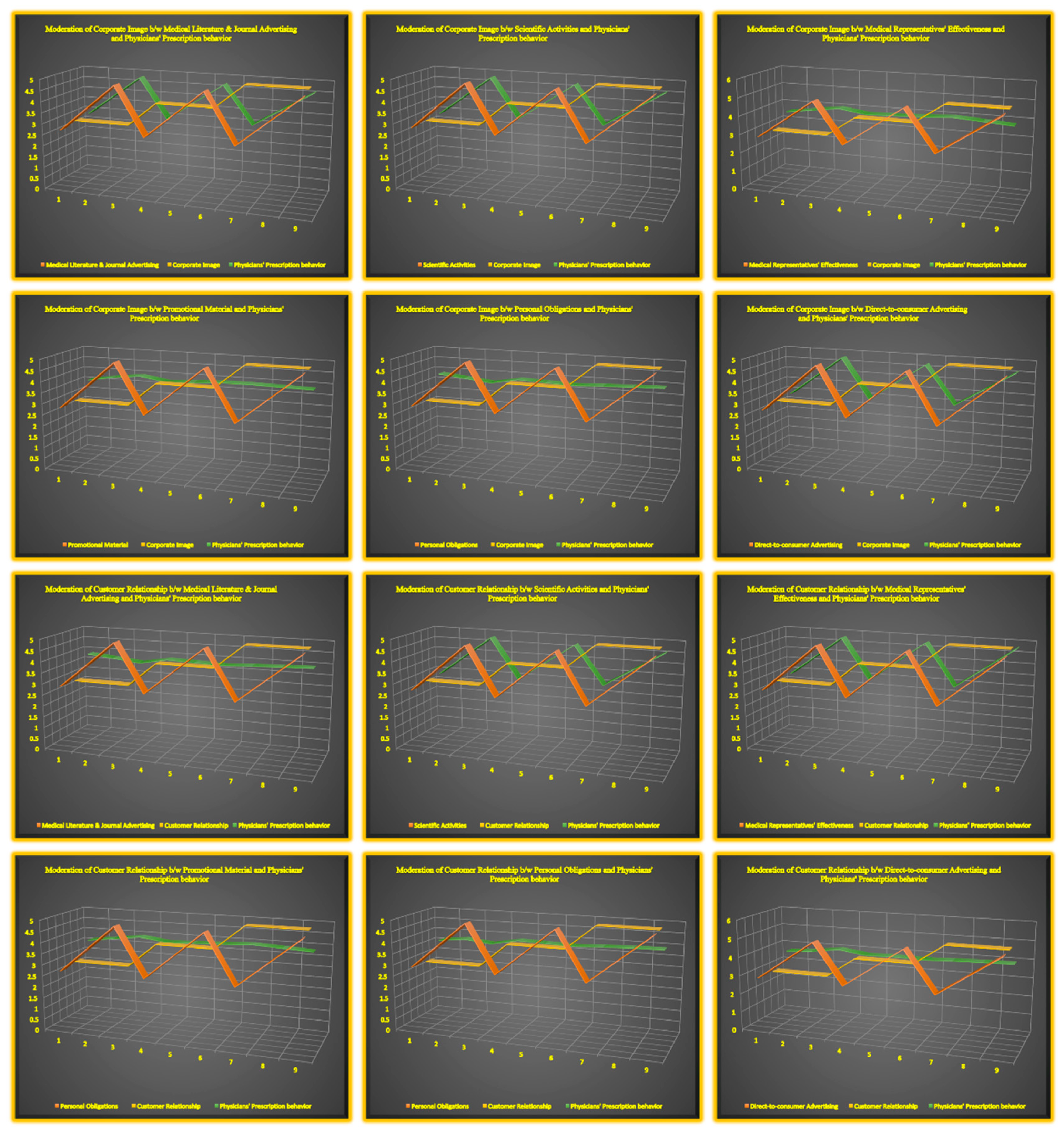

21. Confirmatory Factor Analysis—CFA

22. Structural Equation Modeling—SEM

23. Hypothesized Direct Relationship

24. Moderating Effect of CIM and CRP (Moderation Analysis)

25. R-Square Increment

26. Conditional Effect of CIM and CRP (Moderators)

27. Visualization of Conditional Effect

28. Discussions

29. Conclusions

30. Managerial Policy Implications

31. Limitations and Delimitations of the Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Disclosure Statement

References

- Ahmed, R.R.; Vveinhardt, J.; Štreimikienė, D.; Ashraf, M.; Channar, Z.A. Modified SERVQUAL Model and Effects of Customer Attitude and Technology on Customer Satisfaction in Banking Industry: Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18, 974–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Vveinhardt, J.; Štreimikienė, D.; Awais, M. Mediating and Marketing factors influence the prescription behavior of Physicians: An Empirical Investigation. Amfiteatru Econ. 2016, 18, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Vveinhardt, J.; Štreimikienė, D. The direct and indirect impact of Pharmaceutical industry in Economic expansion and Job creation: Evidence from Bootstrapping and Normal theory methods. Amfiteatru 2018, 20, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikin, K.J.; Swasy, J.L.; Braman, A.C. Patient and Physician Attitudes and Behaviors Associated with DTC Promotion of Prescription Drugs; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2004.

- Alosaimi, F.D.; Al Kaabba, A.; Qadi, M.; Albahlal, A.; Alabdulkarim, Y.; Alabduljabbar, M.; Alqahtani, F. Physicians’ attitudes towards interaction with the pharmaceutical industry/Attitudes des médecins par rapport á l’interaction avec l’industrie pharmaceutique. East. Med. Health J. 2014, 20, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Sullivan, M.W. The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction for Firms. Mark. Sci. 2003, 12, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. Study finds problems in M.D.-sales rep relationship. Pharm Representative, 6 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, U.; Taneja, G. An Analytical Study of Physicians Behavior towards Marketing of Pharmaceutical Products. Indian J. Mark. 2006, 36, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Avlonitis, G.J.; Panagopoulos, N.G. Antecedents and Consequences of CRM Technology Acceptance in the Sales Force. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, R.; Bhardwaj, P. Detailing vs. Direct-to-Consumer Advertising in the Prescription Pharmaceutical Industry. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T.; Greyser, S.A. Managing the multiple identities of the corporation. Calif. Mana. Rev. 2002, 44, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkhahn, R.H.; Jauch, E.; Kramer, D.A.; Nowak, R.M.; Raja, A.S.; Summers, R.L.; Weber, J.E.; Diercks, D.B. A review of the federal guidelines that inform and influence relationships between physicians and industry. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009, 16, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolin, J.H. Hayes, Andrew, F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. J. Educ. Meas. 2014, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltri, J.M.; Gordon, E.R.; Vogel, R.L. Effect of antihypertensive samples on physician prescribing patterns. Fam. Med. 2002, 34, 729–731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowman, M.A.; Pearle, D.L. Changes in drug prescribing patterns related to commercial company funding of continuing medical education. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 1988, 8, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.R.; Evans, D.V.; Fugh-Berman, A. Pharmaceutical industry interactions in family medicine residencies decreased between 2008 and 2013: A CERA study. Fam. Med. 2015, 47, 279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS, Basic Concepts, Application and Programming, 2nd ed.; La Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, E.G.; Gruen, R.L.; Mountford, J.; Miller, L.G.; Cleary, P.D.; Blumenthal, D. A national survey of Physicians-Industry relationships. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Barnes, S.J.; Scornavacca, E.; Fletcher, K. Consumer perceptions and attitudes towards SMS advertising: Recent evidence from New Zealand. Int. J. Advert. 2007, 26, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, T.S.; Johnson, M.S.; Rich, E.C.; McKinney, W.P. Physicians, pharmaceutical representatives, and the cost of prescribing. Arch. Fam. Med. 1996, 5, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetley, A. Problem Drugs; Health Action International: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, L.D.; O’Young, T.S.; Hazlet, T.K.; Bradley, K.A.; Maynard, C.; Lessler, D.S. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimonas, S.; Brennan, T.A.; Rothman, D.J. Physicians and Drug Representatives: Exploring the Dynamics of The Relationship. Soc. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chren, M.M.; Landefeld, C.S. Physicians’ behavior and their interactions with drug companies. A controlled study of physicians who requested additions to a hospital drug formulary. JAMA 1994, 271, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B. Influence: Science and Practice, 3rd ed.; HarperCollins College Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M.M.; Gong, M.; Schork, M.; Evans, D.; Roloff, D.; Hurwitz, M.; Maiman, L.; Mellins, R. Impact of Education for Physicians on Patient Outcomes. Am. J. Pediatr. 1998, 101, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corckburn, J.; Pit, S. Prescribing behaviour in clinical practice: Patients’ expectations and doctors’ perceptions of patients’expectations—A questionnaire study. BMJ 1997, 315, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, C.; Zaleski, I.; Jolly, D.; Durieux, P. Effects of financial incentives on medical practice: Results from a systematic review of the literature and methodological issues. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2000, 12, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.; Chun, R.; da Silva, R.V.; Roper, S. Corporate Reputation and Competitiveness; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Ferrari, A.; Gentille, C.; Davalos, L.; Huayanay, L.; Malaga, G. Attitudes and relationship between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry in a public general hospital in Lima, Peru. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laat, E.; Windmeijer, F.; Douven, R. How Does Pharmaceutical Marketing Influence Doctors’ Prescription Behaviour? CPB Netherlands’ Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2002.

- DeJong, C.; Aguilar, T.; Tseng, C.W.; Lin, G.A.; Boscardin, W.J.; Dudley, R.A. Pharmaceutical Industry Sponsored Meals and Physician Prescribing Patterns for Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.; Takhar, J.; Macnab, J.; Eadie, J.; Lockyer, J.; Stenerson, H.; François, J.; Bell, M. Controlling quality in CME/ CPD by measuring and illuminating bias. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2011, 31, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolovich, L.; Levine, M.; Tarajos, R.; Duku, E. Promoting optimal antibiotic therapy for otitis media using commercially sponsored evidence-based detailing: A prospective controlled trial. Drug Inf. J. 1999, 33, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.R. Corporate Reputations. Strategies for Developing the Corporate Brand; Kogan Page: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, G.R. Creating Corporate Reputations. Identity, Image and Performance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, G.R. Corporate reputations: Should you compete on yours? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elling, M.E.; Fogle, H.J.; McKhann, C.S.; Simon, C. (2002). Making more of pharma’s sales force. McKinsey Q. 2002, 3, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Emory, C.W.; Cooper, D.R. Business Research Methods, 4th ed.; Irvin: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ettenson, R.; Knowles, J. Merging the brands and branding the merger. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2006, 47, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay, S. Prescription Drugs and Mass Media Advertising; National Institute for Health Care Management: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Flavian, C.; Torres, E.; Guinaliu, M. Corporate image measurement. A further problem for the tangibilization of Internet banking services. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2004, 22, 366–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francer, J.; Izquierdo, J.Z.; Music, T.; Narsai, K.; Nikidis, C.; Simmonds, H.; Woods, P. Ethical pharmaceutical promotion and communications worldwide: Codes and regulations. Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 2014, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.A.; Lexchin, J. The cost of pushing pills: A new estimate of pharmaceutical promotion expenditures in the United States. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonül, F.F.; Carter, F.; Petrova, E.; Srinivasan, K. Promotion of Prescription Drugs and its Impact on Physicians’ Choice Behavior. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsi, M.; Wilson, A.M. Corporate reputation: Seeking a definition. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2001, 6, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. Drug Reps. In Targeting Non-Physicians; American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greyser, S.A. Advancing and enhancing corporate reputation. Corp. Commun. J. 1999, 4, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K.E.M.; Sketris, I.; Tett, S.E. Prescription drug samples–Does this marketing strategy counteract policies for quality use of medicines? J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2003, 28, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, Q.; Bero, L.; Malone, R. Interactions between non-physician clinicians and industry: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Nayak, R.P.; Sivaranjani, R. A study on the interactions of doctors with medical representatives of pharmaceutical companies in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital of South India. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2016, 8, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, J.K. The Pharmaceutical Industry’s Influence on Physician Behavior and Health Care Costs. 2002. Available online: https://www.sfms.org/sfm/sfm602a.htm (accessed on 29 May 2003).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R. The strategic analysis of intangible resorces. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, E.C.; Hutchison, P.; Barrier, R., Jr. A population-based study of the prevalence and influence of gifts to radiation oncologists from pharmaceutical companies and medical equipment manufacturers. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 59, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hersh, W.R.; Crabtree, K.M.; Hickam, D.H.; Sacherek, Y.; Friedman, C.P.; Tidmarch, P.; Mosbaek, C.; Kramier, D. Factors associated with success in searching MEDLINE and applying evidence to answer clinical questions. J. Am. Med. Informat. Assoc. 2002, 9, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzenstein, M.; Misra, S.; Posavac, S.S. How consumers’ attitudes toward direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs influence ad effectiveness, and consumer and physician behavior. Mark. Lett. 2004, 15, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmer, A.F. Industry strongly supports continuing medical education. JAMA 2001, 285, 2012–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.H.; Lee, B.C.Y.; Ho, S.H. Consumer attitude toward grey market goods. Int. Mark. Rev. 2004, 21, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, M.P.; Stafford, R.S.; Lane, A.T. Characterizing the relationship between free drug samples and prescription patterns for acne vulgaris and rosacea. JAMA Dermatol. 2014, 150, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, E.D.; Nebenzahl, I.D. National Image & Competitive Advantage, the Theory and Practice of Place Branding, 2nd ed.; Copenhagen Business School Press: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Holmberg, C.; Russell, J.; Bochenek, T.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Fischer, C.; Tinnemann, P. Perceptions and Attitudes of Egyptian Health Professionals and Policy-Makers towards Pharmaceutical Sales Representatives and Other Promotional Activities. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.; Caplan, A.L.; Merz, J.F. All gifts large and small. Am. J. Bioethics 2003, 2, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesselheim, A.S.; Mello, M.M.; Studdert, D.M. Strategies and practices in off label marketing of pharmaceuticals: A retrospective analysis of whistleblower complaints. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1000431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Naqvi, A.; Ahmad, R.; Ahmed, F.; McGarry, K.; Fazlani, R.; Ahsan, M. Perceptions and Attitudes of Medical Sales Representatives (MSRs) and Prescribers Regarding Pharmaceutical Sales Promotion and Prescribing Practices in Pakistan. J. Young Pharm. 2016, 8, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeflang, P.S.H.; Wieringa, J.E. Modeling the effects of pharmaceutical marketing. Mark. Lett. 2010, 21, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffler, K.B. Persuasion or Information? The Economics of Prescription Drug Advertising. J. Law Econ. 1981, 24, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexchin, J. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: What does the literature say? Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1993, 14, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Lieb, K.; Koch, C. Medical students’ attitudes to and contact with the pharmaceutical industry: A survey at eight German university hospitals. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2013, 110, 584–590. [Google Scholar]

- Lieb, K.; Scheurich, A. Contact between Doctors and the Pharmaceutical Industry, Their Perceptions, and the Effects on Prescribing Habits. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebman, M. Rethinking sampling strategies. Med. Mark. Media 1997, 32, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Gupta, S. The impact of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs on physician visits and drug request: Empirical findings and public policy implications. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2011, 28, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loden, D.J.; Liebman, M. High Compression Marketing Supercharges Drug Revenues. 2000. Available online: https://www.mmm-online.com/mmm-magazine/ (accessed on 21 March 2001).

- Lotfi, T.; Morsi, R.Z.; Rajabbik, M.H.; Alkhaled, L.; Kahale, L.; Hala, N.; Brax, H.; Fadiallah, R.; Aki, E.A. Knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of physicians in low and middle-income countries regarding interacting with pharmaceutical companies: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurie, N.; Rich, E.C.; Simpson, D.E.; Meyer, J.; Schiedermayer, D.L.; Goodman, J.L.; McKinney, W.P. Pharmaceutical representatives in academic medical centers. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1990, 5, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.; Zhang, S.; Hong, S. Sample size in Factor Analysis. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowska, M. Interactions between doctors and pharmaceutical sales representatives in a former communist country, the ethical issues. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2014, 23, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, P.; Phil, M.; Honka, E. The Effects and Role of Direct-to-Physician Marketing in the Pharmaceutical Industry: An Integrative Review. Yale J. Health Policy Law Ethics 2005, 5, 785–822. [Google Scholar]

- Marco, C.A.; Moskop, J.C.; Solomon, R.C.; Geiderman, J.M.; Larkin, G.L. Gifts to Physicians from the Pharmaceutical Industry: An Ethical Analysis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2006, 48, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markwick, N.; Fill, C. Towards a framework for managing corporate identity. Eur. J. Mark. 1997, 31, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, I.; Ibrahim, M.; Hassali, M.; Ahmad, M. Evolution of marketing techniques, Adoption in Pharmaceutical Industry and related issues: A review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2009, 7, 1942–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.N. Drug makers and continuing medical education. Indian Pediatr. 2000, 37, 626–630. [Google Scholar]

- Mizik, N.; Jacobson, R. Are physicians “easy marks”? Quantifying the effects of detailing and sampling on new prescriptions. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 1704–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montastruc, F.; Moulis, G.; Palmaro, A.; Gardette, V.; Durrieu, G.; Montastruc, J.-L. Interactions between medical residents and drug companies: A national survey after the Mediator® affair. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherji, P. Estimating the effects of direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription medicines: A natural experiment. In Proceedings of the Marketing Science Conference, Rotterdam, NL, USA, 24–26 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mulinari, S. Unhealthy marketing of pharmaceutical products: An international public health concern. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, H.S.; Manchanda, P.; Bhatia, T. Asymmetric social interactions in physician prescription behavior: The role of opinion leaders. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Desiraju, R.; Chintagunta, P.K. Return on Investment Implications for Pharmaceutical Promotional Expenditures: The Role of Marketing-Mix Interactions. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.J.; Goldsmith, R.E. The development of a scale to measure perceived corporate credibility. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, J.P.; Wateska, L. The effects of pharmaceutical firm enticements on physician prescribing patterns. There’s no such thing as a free lunch. Chest 1992, 102, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinga, E.C.; Leeflang, P.S.; Wieringa, J.E. Early Marketing Matters: A Time-Varying Parameter Approach to Persistence. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.; Vitry, A.I.; Roughead, E.E.; Ismail, S.B.; Omar, K. Medicines information provided by pharmaceutical representatives: A comparative study in Australia and Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, K.; Fleischman, W.; Agrawal, S. Industry relationships with pediatricians: Findings from the open payments sunshine act. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppin, J.F. Pharmaceutical sales representatives and physicians: Ethical considerations of a relationship. J. Med. Philos. 1996, 21, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, C.A.S.O.; Green, D.; Baby, A.R.; Ruas, G.W.; Kaneko, T.M.; Marana, S.R.; Velasco, M.V.R. Determination of papain activity in topical dosage forms: Single laboratory validation assay. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2007, 26, 771–775. [Google Scholar]

- Pirisi, A. Patient-direct drug advertising puts pressure on US doctors. Lancet 1999, 354, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Agarwal, S.; Tuddenham, S.; Peto, H.; Iqbal, M.; Bhuiya, A.; Peters, D.H. What do they do? Interactions between village doctors and medical representatives in Chakaria, Bangladesh. Int. Health 2015, 7, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relman, A.S. Separating continuing medical education from pharmaceutical marketing. JAMA 2001, 285, 2009–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, J. Advertising and competition in the ethical pharmaceutical industry: The case of antihypertensive drugs. J. Law Econ. 1999, 42, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, G.S.W.; Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate data analysis. Statistician 1988, 37, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Mukohara, K.; Bito, S. Japanese practicing physicians’ relationships with pharmaceutical representatives: A national survey. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.C. Interaction between pharmaceutical companies and physicians who prescribe antiretroviral drugs for treating AIDS. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2014, 132, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzman, D. Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Shalowitz, D.I.; Spillman, M.A.; Morgan, M.A. Interactions with industry under the Sunshine Act: An example from gynecologic oncology. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, U.T.; Shakoor, A.; Kiani, S.; Ali, F.; Sharif, M.; Kumar, A.; Raza, Q.; Khan, N.; Alamzaib, S.M.; Farid-ul-Husnain, S. Attitudes of medical students towards incentives offered by pharmaceutical companies—Perspective from a developing nation—A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Ethics 2014, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.D. Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2008, 9, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spingarn, R.W.; Berlin, J.A.; Strom, B.L. When pharmaceutical manufacturers’ employees present grand rounds, what do residents remember? Acad. Med. 1996, 71, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafford, R.S.; Furberg, C.D.; Finkelstein, S.N.; Cockburn, I.M.; Alehegn, T. Impact of clinical trial results on national trends in alpha-blocker prescribing, 1996–2002. JAMA 2004, 291, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stros, M.; Hari, J.; Marriott, J. The Relevance of Marketing Activities in The Swiss Prescribing Drugs Market: Two Empirical Studies. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 2009, 3, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, G. Influence of Promotional Tools Offered by Pharmaceutical Industry on Physicians Prescribing Behavior. 2007. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2049747 (accessed on 22 September 2010).

- Van den Bosch, C.; de Jong, M. How corporate visual identity supports reputation. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2005, 10, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bulte, C.; Lilien, G.L. Medical Innovation Revisited: Social Contagion versus Marketing Effort. Am. J. Sociol. 2001, 106, 1409–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicciardo, L.J. The secret weapon in marketing intelligence: Meetings and events analysis is a powerful new tool in researching marketing strategy and success. Med. Mark. Media 1995, 30, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C.; Moore, L.; Harvey, I.; Carthy, P.; Robinson, E.; Brawn, R. Attitudes and Behavior of General Practitioners and Their Prescribing Costs: A National Cross Sectional Survey. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2003, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazana, A. Doctors and the Pharmaceutical Industry Is A Gift Ever Just A Gift? J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000, 283, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, M.S.; Doblin, B.H.; Shapiro, M.F. Pharmaceutical advertisements in leading medical journals: Experts’ assessments. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992, 116, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windmeijer, F.; De Laat, E.; Douven, R.; Mot, E. Pharmaceutical promotion and GP prescription behaviour. Health Econ. 2005, 15, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worcester, R. Corporate Image. In Consumer Market Research Handbook; Worcester, R., Downham, J., Eds.; McGraw Hill: London, UK, 1986; pp. 601–606. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, J.S.; Austad, K.E.; Franklin, J.M.; Chimonas, S.; Campbell, E.G.; Avorn, J.; Kesselheim, A.S. Association of medical students’ reports of interactions with the pharmaceutical and medical device industries and medical school policies and characteristics: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.S.; Franklin, J.M.; Avorn, J.; Landon, J.; Kesselheim, A.S. Association of Industry Payments to Physicians With the Prescribing of Brand name Statins in Massachusetts. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, M.G. The Accuracy of Drug Information from Pharmaceutical Sales Representatives. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1995, 273, 1296–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 428 | 57.8% | |

| Female | 312 | 42.2% | |

| Marital Status | Single | 295 | 39.9% |

| Married | 426 | 57.6% | |

| Divorced | 19 | 2.6% | |

| Age (In Years) | 20–30 | 266 | 35.9% |

| 30–40 | 164 | 22.2% | |

| 40–50 | 96 | 13.0% | |

| 50–60 | 124 | 16.8% | |

| More than 60 | 90 | 12.2% | |

| Education | Graduation | 326 | 44.1% |

| Post-Graduation (Local) | 227 | 30.7% | |

| Post Graduation (Foreign) | 123 | 16.6% | |

| PhD degree | 64 | 8.6% | |

| Experience (In Years) | 1–5 | 201 | 27.2% |

| 5–10 | 218 | 29.5% | |

| 10–15 | 99 | 13.4% | |

| 15–20 | 103 | 13.9% | |

| More than 20 | 119 | 16.1% | |

| Income (In PKR 000) | 30–60 | 121 | 16.4% |

| 60–90 | 332 | 44.9% | |

| 90–120 | 154 | 20.8% | |

| 120–150 | 80 | 10.8% | |

| More than 150 | 53 | 7.2% | |

| Total–N | 740 | ||

| Statistics | PPB | MLJ | SAC | MRE | PMT | POB | DTCA | CIM | CRP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Valid | 740 | 740 | 740 | 740 | 740 | 740 | 740 | 740 | 740 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean | 3.8027 | 3.9757 | 3.9311 | 3.9662 | 3.9324 | 3.8797 | 4.0270 | 3.9311 | 4.0608 | |

| Std. Deviation | 1.0832 | 1.1227 | 1.1008 | 1.1182 | 1.1014 | 1.0726 | 0.9517 | 1.0137 | 1.0249 | |

| Skewness | −0.928 | −1.010 | −0.986 | −1.004 | −0.987 | −0.973 | −1.083 | −0.940 | −1.105 | |

| Std. Error of Skewness | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 | |

| Kurtosis | 0.359 | 0.376 | 0.450 | 0.389 | 0.447 | 0.575 | 1.472 | 0.664 | 0.923 | |

| Std. Error of Kurtosis | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.179 | |

| Factors | Items | FL | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians’ prescription behaviour | PPB1 | 0.804 | 0.837 | 0.876 | 0.702 |

| PPB2 | 0.897 | ||||

| PPB3 | 0.81 | ||||

| Medical literature & Journal advertising | MLJ1 | 0.924 | 0.870 | 0.928 | 0.766 |

| MLJ2 | 0.88 | ||||

| MLJ3 | 0.959 | ||||

| MLJ4 | 0.718 | ||||

| Scientific activities | SAC1 | 0.807 | 0.884 | 0.936 | 0.786 |

| SAC2 | 0.92 | ||||

| SAC3 | 0.822 | ||||

| SAC4 | 0.986 | ||||

| Medical representative effectiveness | MRE1 | 0.854 | 0.842 | 0.880 | 0.709 |

| MRE2 | 0.835 | ||||

| MRE3 | 0.838 | ||||

| Promotional material | PMT1 | 0.780 | 0.824 | 0.864 | 0.680 |

| PMT2 | 0.884 | ||||

| PMT3 | 0.807 | ||||

| Personal obligations | POB1 | 0.831 | 0.826 | 0.867 | 0.684 |

| POB2 | 0.872 | ||||

| POB3 | 0.776 | ||||

| Direct-to-consumer-advertising (DTCA) | DTC1 | 0.845 | 0.838 | 0.877 | 0.703 |

| DTC2 | 0.874 | ||||

| DTC3 | 0.795 | ||||

| Corporate Image | CIM1 | 0.766 | 0.843 | 0.882 | 0.714 |

| CIM2 | 0.841 | ||||

| CIM3 | 0.921 | ||||

| Customer Relationship | CRP1 | 0.768 | 0.827 | 0.868 | 0.687 |

| CRP2 | 0.819 | ||||

| CRP3 | 0.894 |

| Factors | Items | Factor Loadings of Components | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPB | MLJ | SAC | MRE | PMT | POB | DTC | CIM | CRP | ||

| Physicians’ prescription behavior | PPB1 | 0.804 | ||||||||

| PPB2 | 0.897 | |||||||||

| PPB3 | 0.81 | |||||||||

| Medical literature & Journal advertising | MLJ1 | 0.924 | ||||||||

| MLJ2 | 0.88 | |||||||||

| MLJ3 | 0.959 | |||||||||

| MLJ4 | 0.718 | |||||||||

| Scientific activities | SAC1 | 0.807 | ||||||||

| SAC2 | 0.92 | |||||||||

| SAC3 | 0.822 | |||||||||

| SAC4 | 0.986 | |||||||||

| Medical representatives’ effectiveness | MRE1 | 0.854 | ||||||||

| MRE2 | 0.835 | |||||||||

| MRE3 | 0.838 | |||||||||

| Promotional material | PMT1 | 0.780 | ||||||||

| PMT2 | 0.884 | |||||||||

| PMT3 | 0.807 | |||||||||

| Personal obligations | POB1 | 0.831 | ||||||||

| POB2 | 0.872 | |||||||||

| POB3 | 0.776 | |||||||||

| Direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) | DTC1 | 0.845 | ||||||||

| DTC2 | 0.874 | |||||||||

| DTC3 | 0.795 | |||||||||

| Corporate Image | CIM1 | 0.766 | ||||||||

| CIM2 | 0.841 | |||||||||

| CIM3 | 0.921 | |||||||||

| Customer Relationship | CRP1 | 0.768 | ||||||||

| CRP2 | 0.819 | |||||||||

| CRP3 | 0.894 | |||||||||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | 0.772 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 24,266.468 |

| Df | 703 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| Factors | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 6.748 | 17.759 | 17.759 | 6.748 | 17.759 | 17.759 | 6.577 | 17.309 | 17.309 |

| 2 | 3.726 | 9.806 | 27.565 | 3.726 | 9.806 | 27.565 | 2.638 | 6.942 | 24.251 |

| 3 | 2.965 | 7.804 | 35.368 | 2.965 | 7.804 | 35.368 | 2.636 | 6.938 | 31.189 |

| 4 | 2.708 | 7.127 | 42.495 | 2.708 | 7.127 | 42.495 | 2.629 | 6.919 | 38.108 |

| 5 | 2.624 | 6.906 | 49.401 | 2.624 | 6.906 | 49.401 | 2.625 | 6.909 | 45.017 |

| 6 | 2.564 | 6.749 | 56.150 | 2.564 | 6.749 | 56.150 | 2.611 | 6.872 | 51.889 |

| 7 | 2.425 | 6.383 | 62.533 | 2.425 | 6.383 | 62.533 | 2.601 | 6.845 | 58.734 |

| 8 | 2.293 | 6.034 | 68.567 | 2.293 | 6.034 | 68.567 | 2.570 | 6.762 | 65.496 |

| 9 | 2.093 | 5.508 | 74.075 | 2.093 | 5.508 | 74.075 | 2.517 | 6.625 | 72.120 |

| Factors | PPB | MLJ | SAC | MRE | PMT | POB | DTCA | CIM | CRP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-image Correlation | PPB | 0.909 a | −0.093 | −0.245 | −0.078 | −0.561 | −0.056 | 0.084 | −0.015 | −0.044 |

| MLJ | −0.093 | 0.946 a | 0.039 | −0.276 | −0.070 | −0.272 | 0.078 | −0.182 | 0.034 | |

| SAC | −0.245 | 0.039 | 0.877 a | −0.684 | −0.109 | −0.135 | −0.055 | −0.043 | 0.049 | |

| MLJ effectiveness | −0.078 | −0.276 | −0.684 | 0.870 a | 0.095 | −0.058 | −0.024 | 0.128 | −0.080 | |

| PMT | −0.561 | −0.070 | −0.109 | 0.095 | 0.890 a | −0.356 | −0.097 | 0.056 | 0.037 | |

| POB obligations | −0.056 | −0.272 | −0.135 | −0.058 | −0.356 | 0.944 a | 0.036 | −0.029 | 0.021 | |

| DTCA | 0.084 | 0.078 | −0.055 | −0.024 | −0.097 | 0.036 | 0.706 a | −0.394 | −0.662 | |

| CIM | −0.015 | −0.182 | −0.043 | 0.128 | 0.056 | −0.029 | −0.394 | 0.826 a | −0.259 | |

| CRP | −0.044 | 0.034 | 0.049 | −0.080 | 0.037 | 0.021 | −0.662 | −0.259 | 0.732 a | |

| Goodness of Fit Measures | Absolute Fit Indices | Relative Fit Indices | Non-Centrality-Based Indices | Parsimonious Fit Indices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | Probability | GFI | NFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | RNI | PCFI | PNFI | |

| Measurement Model | 3.11 | 0.0043 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.003 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.86 |

| Structural Model | 3.25 | 0.0048 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.004 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| Criterion (Threshold values) | <5.0 | <0.05 | >0.95 | >0.90 | >0.95 | >0.95 | >0.95 | <0.05 | >0.95 | >0.75 | >0.75 |

| Hypothesis | Variables | Regression Paths | Standardized Regression Weights (β) | SE | T | P | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Med Lit & Journal advertising | MLJ † → PPB | 0.811 | 0.015 | 54.09 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | Scientific activities | SAC † → PPB | 0.897 | 0.012 | 74.55 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | Medical Rep effectiveness | MRE † → PPB | 0.853 | 0.013 | 64.37 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | Promotional material | PMT † → PPB | 0.915 | 0.011 | 81.46 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | Personal obligations | POB † → PPB | 0.888 | 0.013 | 63.97 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | Direct-to-consumer advertising | DTC † → PPB | 0.791 | 0.014 | 44.11 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Hypotheses | Moderators | Moderation | Coefficient | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderating Effect of the CIM and CRP b/w MLJ and PPB | ||||||||

| H7A: | CIM | MLJ × CIM | −0.0343 | 0.0122 | −2.83 | 0.0049 | −0.0582 | −0.0105 |

| H8A: | CRP | MLJ × CRP | −0.0208 | 0.0120 | −1.74 | 0.0831 | −0.0443 | 0.0027 |

| Moderating Effect of the CIM and CRP b/w SAC and PPB | ||||||||

| H7B | CIM | SAC ×CIM | −0.0263 | 0.0089 | −2.94 | 0.0034 | −0.0439 | −0.0087 |

| H8B | CRP | SAC × CRP | −0.0343 | 0.0090 | −3.80 | 0.0002 | −0.0521 | −0.0166 |

| Moderating Effect of the CIM and CRP b/w MRE and PPB | ||||||||

| H7C: | CIM | MRE × CIM | −0.0201 | 0.0104 | −1.93 | 0.0540 | −0.0405 | 0.0003 |

| H8C: | CRP | MRE × CRP | −0.0349 | 0.0103 | −3.40 | 0.0007 | −0.0551 | −0.0147 |

| Moderating Effect of the CIM and CRP b/w PMT and PPB | ||||||||

| H7D: | CIM | PMT × CIM | −0.0131 | 0.0090 | −1.45 | 0.1476 | −0.0308 | 0.0046 |

| H8D: | CRP | PMT × CRP | −0.0143 | 0.0089 | −1.60 | 0.1090 | −0.0319 | 0.0032 |

| Moderating Effect of the CIM and CRP b/w POB and PB | ||||||||

| H7E: | CIM | POB × CIM | −0.0224 | 0.0112 | −1.99 | 0.0469 | −0.0444 | −0.0003 |

| H8E: | CRP | POB × CRP | −0.0136 | 0.0108 | −1.25 | 0.2116 | −0.0348 | 0.0077 |

| Moderating Effect of the CIM and CRP b/w DTC and PPB | ||||||||

| H7F: | CIM | DTC × CIM | −0.0552 | 0.0157 | −3.52 | 0.0005 | −0.0859 | −0.0244 |

| H8F: | CRP | DTC × CRP | −0.0029 | 0.0376 | −0.76 | 0.9392 | −0.0766 | 0.0709 |

| Moderation | R2-Changed | F | df1 | df2 | P * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLJ × CIM | 0.0018 | 7.9810 | 1 | 736 | 0.0049 |

| MLJ × CRP | 0.0006 | 3.0113 | 1 | 736 | 0.0831 |

| SAC × CIM | 0.0010 | 8.6490 | 1 | 736 | 0.0034 |

| SAC × CRP | 0.0017 | 14.4272 | 1 | 736 | 0.0002 |

| MRE × CIM | 0.0006 | 3.7233 | 1 | 736 | 0.0540 |

| MRE × CRP | 0.0018 | 11.5312 | 1 | 736 | 0.0007 |

| PMT × CIM | 0.0002 | 2.1016 | 1 | 736 | 0.1476 |

| PMT × CRP | 0.0003 | 2.5755 | 1 | 736 | 0.1090 |

| POB × CIM | 0.0007 | 3.9637 | 1 | 736 | 0.0469 |

| POB × CRP | 0.0003 | 1.5635 | 1 | 736 | 0.2116 |

| DTC × CIM | 0.0042 | 12.4019 | 1 | 736 | 0.0005 |

| DTC × CRP | 0.0000 | 0.0058 | 1 | 736 | 0.9392 |

| Conditional effect of MLJ on PPB on different values of the CIM | ||||||

| CIM | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 2.9173 | 0.8398 | 0.0184 | 45.55 | 0.0000 | 0.8036 | 0.8760 |

| 3.9311 | 0.8050 | 0.0157 | 51.22 | 0.0000 | 0.7742 | 0.8359 |

| 4.9448 | 0.7702 | 0.0214 | 36.00 | 0.0000 | 0.7282 | 0.8122 |

| Conditional effect of MLJ on PPB on different values of the CRP | ||||||

| CRP | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 3.0359 | 0.8223 | 0.0171 | 48.21 | 0.0000 | 0.7888 | 0.8558 |

| 4.0608 | 0.8010 | 0.0155 | 51.69 | 0.0000 | 0.7706 | 0.8314 |

| 5.0000 | 0.7815 | 0.0214 | 36.52 | 0.0000 | 0.7395 | 0.8235 |

| Conditional effect of SAC on PPB on different values of the CIM | ||||||

| CIM | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 2.9173 | 0.9195 | 0.0133 | 69.07 | 0.0000 | 0.8934 | 0.9456 |

| 3.9311 | 0.8928 | 0.0126 | 70.72 | 0.0000 | 0.8681 | 0.9176 |

| 4.9448 | 0.8662 | 0.0175 | 49.53 | 0.0000 | 0.8319 | 0.9005 |

| Conditional effect of SAC on PPB on different values of the CRP | ||||||

| CRP | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 3.0359 | 0.9279 | 0.0131 | 70.66 | 0.0000 | 0.9021 | 0.9537 |

| 4.0608 | 0.8927 | 0.0125 | 71.31 | 0.0000 | 0.8681 | 0.9173 |

| 5.0000 | 0.8605 | 0.0171 | 50.28 | 0.0000 | 0.8269 | 0.8941 |

| Conditional effect of MRE on PPB on different values of the CIM | ||||||

| CIM | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 2.9173 | 0.8677 | 0.0152 | 57.21 | 0.0000 | 0.8379 | 0.8975 |

| 3.9311 | 0.8474 | 0.0138 | 61.23 | 0.0000 | 0.8202 | 0.8745 |

| 4.9448 | 0.8270 | 0.0194 | 42.67 | 0.0000 | 0.7890 | 0.8650 |

| Conditional effect of MRE on PPB on different values of the CRP | ||||||

| CRP | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 3.0359 | 0.8853 | 0.0153 | 57.81 | 0.0000 | 0.8552 | 0.9154 |

| 4.0608 | 0.8495 | 0.0137 | 62.22 | 0.0000 | 0.8227 | 0.8763 |

| 5.0000 | 0.8168 | 0.0184 | 44.49 | 0.0000 | 0.7807 | 0.8528 |

| Conditional effect of PMT on PPB on different values of the CIM | ||||||

| CIM | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 2.9173 | 0.9259 | 0.0127 | 72.65 | 0.0000 | 0.9009 | 0.9509 |

| 3.9311 | 0.9126 | 0.0117 | 78.18 | 0.0000 | 0.8897 | 0.9356 |

| 4.9448 | 0.8994 | 0.0167 | 53.95 | 0.0000 | 0.8666 | 0.9321 |

| Conditional effect of PMT on PPB on different values of the CRP | ||||||

| CRP | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 3.0359 | 0.9271 | 0.0126 | 73.53 | 0.0000 | 0.9023 | 0.9518 |

| 4.0608 | 0.9124 | 0.0116 | 78.50 | 0.0000 | 0.8896 | 0.9352 |

| 5.0000 | 0.8989 | 0.0161 | 55.70 | 0.0000 | 0.8672 | 0.9306 |

| Conditional effect of POB on PPB on different values of the CIM | ||||||

| CIM | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 2.9173 | 0.9065 | 0.0154 | 58.83 | 0.0000 | 0.8763 | 0.9368 |

| 3.9311 | 0.8839 | 0.0148 | 59.86 | 0.0000 | 0.8549 | 0.9129 |

| 4.9448 | 0.8612 | 0.0214 | 40.26 | 0.0000 | 0.8192 | 0.9032 |

| Conditional effect of POB on PPB on different values of the CRP | ||||||

| CRP | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 3.0359 | 0.8985 | 0.0150 | 60.05 | 0.0000 | 0.8692 | 0.9279 |

| 4.0608 | 0.8846 | 0.0147 | 60.33 | 0.0000 | 0.8558 | 0.9134 |

| 5.0000 | 0.8719 | 0.0206 | 42.36 | 0.0000 | 0.8315 | 0.9123 |

| Conditional effect of DTC on PPB on different values of the CIM | ||||||

| CIM | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 2.9173 | 0.8652 | 0.0248 | 34.83 | 0.0000 | 0.8164 | 0.9140 |

| 3.9311 | 0.8054 | 0.0196 | 41.14 | 0.0000 | 0.7669 | 0.8438 |

| 4.9448 | 0.7455 | 0.0270 | 27.65 | 0.0000 | 0.6926 | 0.7984 |

| Conditional effect of DTC on PPB on different values of the CRP | ||||||

| CRP | Effect | SE | T | P * | LLCI | ULCI |

| 3.0359 | 0.1314 | 0.0975 | 1.35 | 0.1784 | −0.0601 | 0.3228 |

| 4.0608 | 0.1284 | 0.0929 | 1.38 | 0.1674 | −0.0540 | 0.3109 |

| 5.0000 | 0.1257 | 0.1022 | 1.23 | 0.2189 | −0.0748 | 0.3263 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, R.R.; Channar, Z.A.; Soomro, R.H.; Vveinhardt, J.; Streimikiene, D.; Parmar, V. Antecedents of Symmetry in Physicians’ Prescription Behavior: Evidence from SEM-Based Multivariate Approach. Symmetry 2018, 10, 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym10120721

Ahmed RR, Channar ZA, Soomro RH, Vveinhardt J, Streimikiene D, Parmar V. Antecedents of Symmetry in Physicians’ Prescription Behavior: Evidence from SEM-Based Multivariate Approach. Symmetry. 2018; 10(12):721. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym10120721

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Rizwan Raheem, Zahid Ali Channar, Riaz Hussain Soomro, Jolita Vveinhardt, Dalia Streimikiene, and Vishnu Parmar. 2018. "Antecedents of Symmetry in Physicians’ Prescription Behavior: Evidence from SEM-Based Multivariate Approach" Symmetry 10, no. 12: 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym10120721

APA StyleAhmed, R. R., Channar, Z. A., Soomro, R. H., Vveinhardt, J., Streimikiene, D., & Parmar, V. (2018). Antecedents of Symmetry in Physicians’ Prescription Behavior: Evidence from SEM-Based Multivariate Approach. Symmetry, 10(12), 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym10120721