Spatial Distribution and Driving Mechanisms of Soil Organic Carbon in the Yellow River Source Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Related Work

1.2.1. Model Simulation and Digital Mapping of SOC

1.2.2. Spatiotemporal Distribution of SOC

1.2.3. Driving Factors of Soil Organic Carbon

1.2.4. Research Aim

- To construct an optimal SOC prediction model for the SRYR based on multi-source environmental data and machine learning approaches, accurately capturing the spatial distribution of the 0–20 cm soil layer;

- To systematically analyze the spatiotemporal dynamics of SOC using the optimal model, identify key driving factors, and clarify their underlying mechanisms;

- To quantitatively evaluate the carbon sequestration function of SOC based on its spatiotemporal dynamics and estimate the associated ecological and economic values.

2. Materials and Methods

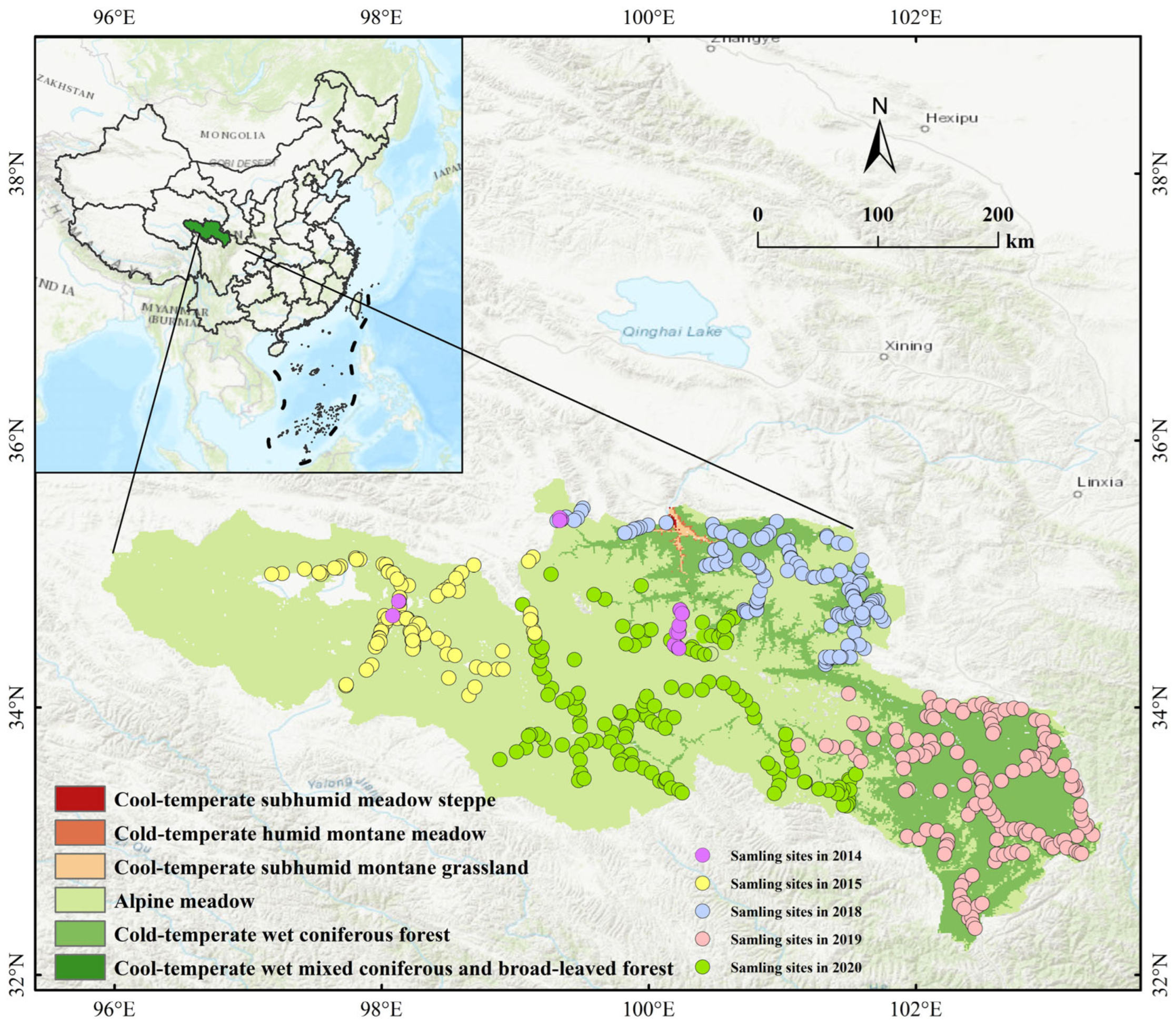

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Resource

2.2.1. Measured SOC Data and Processing

2.2.2. Environmental Variables

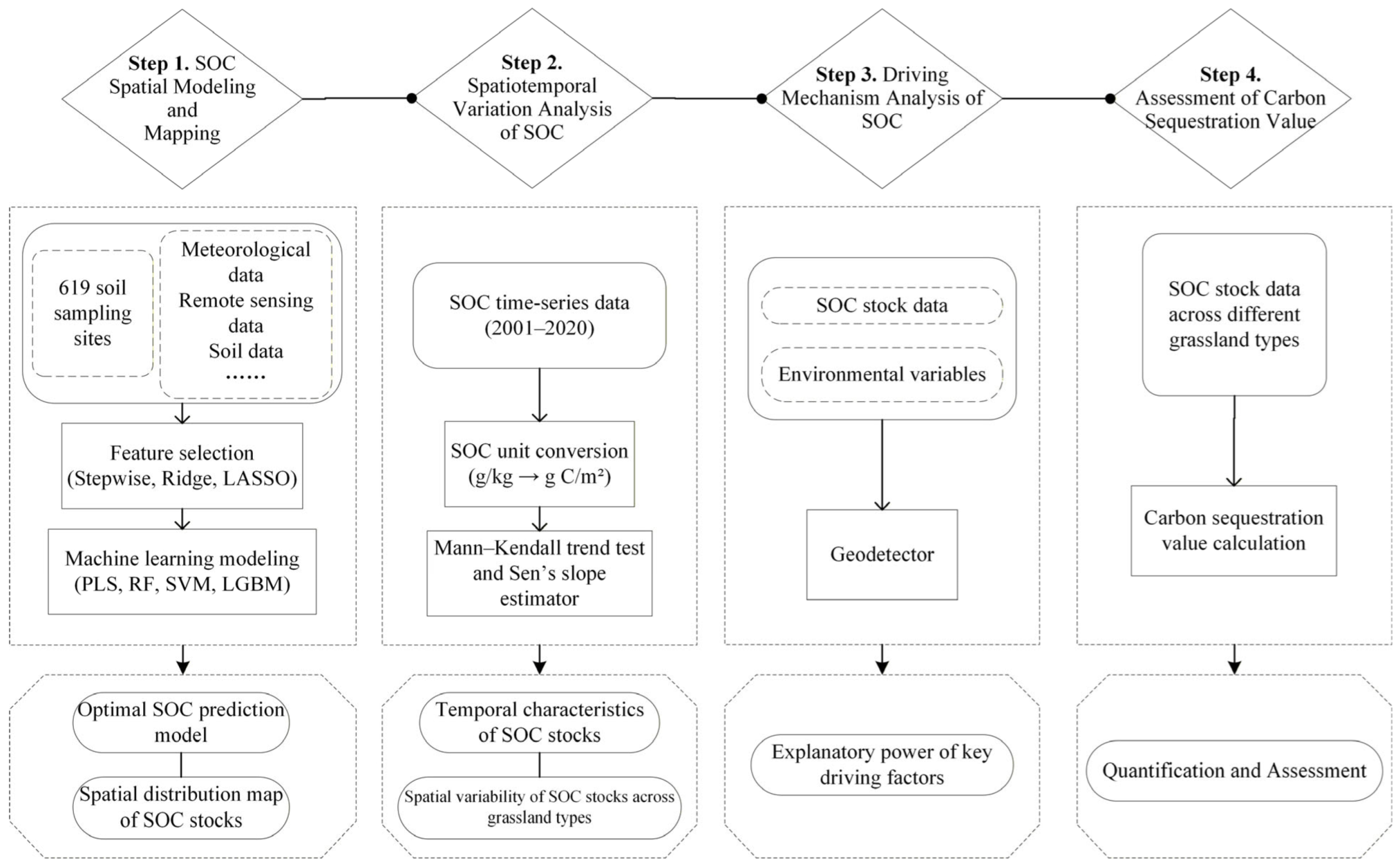

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Variable Selection

2.3.2. Machine Learning Methods

2.3.3. SOC Unit Conversion

2.3.4. Spatiotemporal Analysis of SOC

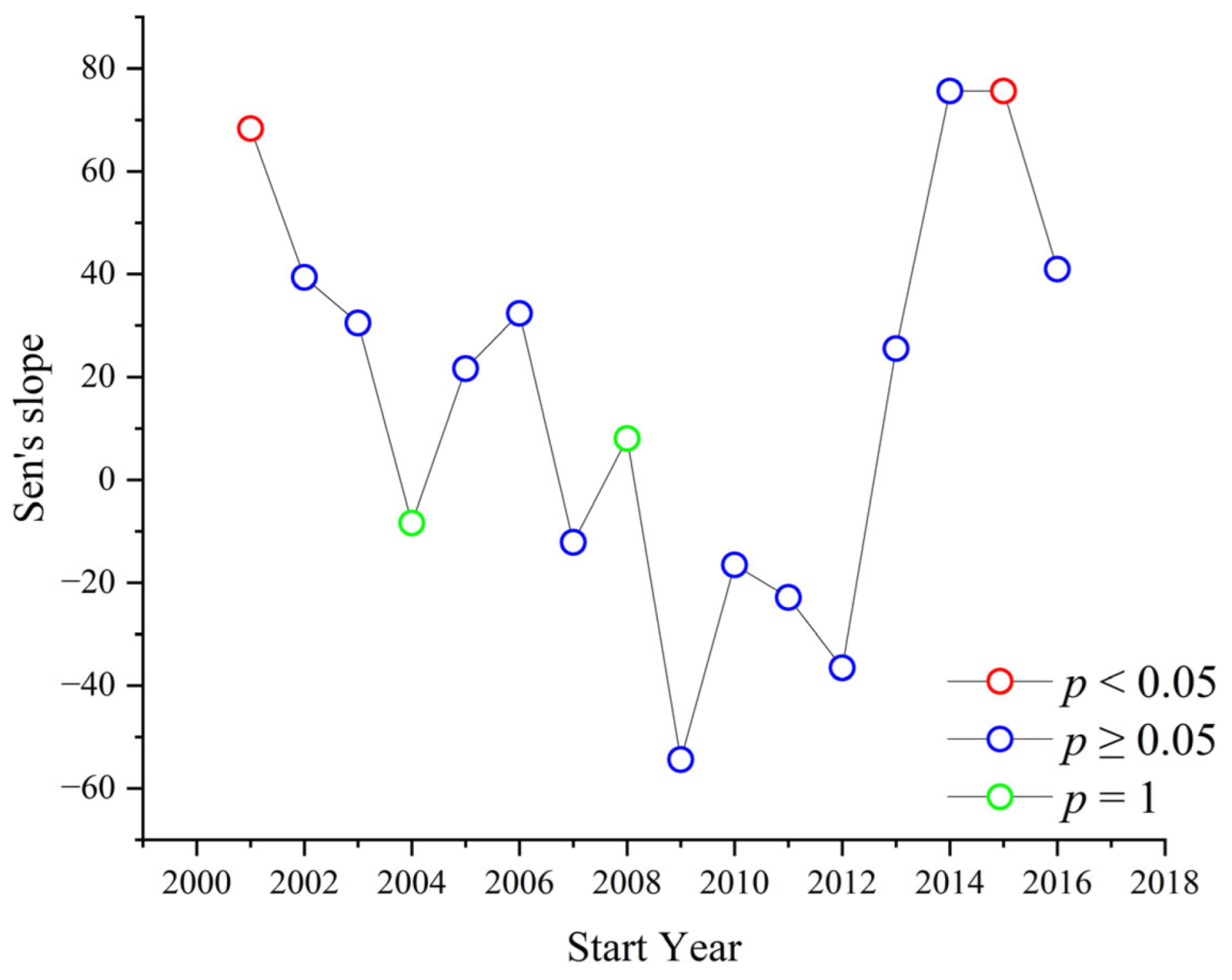

Mann–Kendall Trend Test and Sen’s Slope Estimation

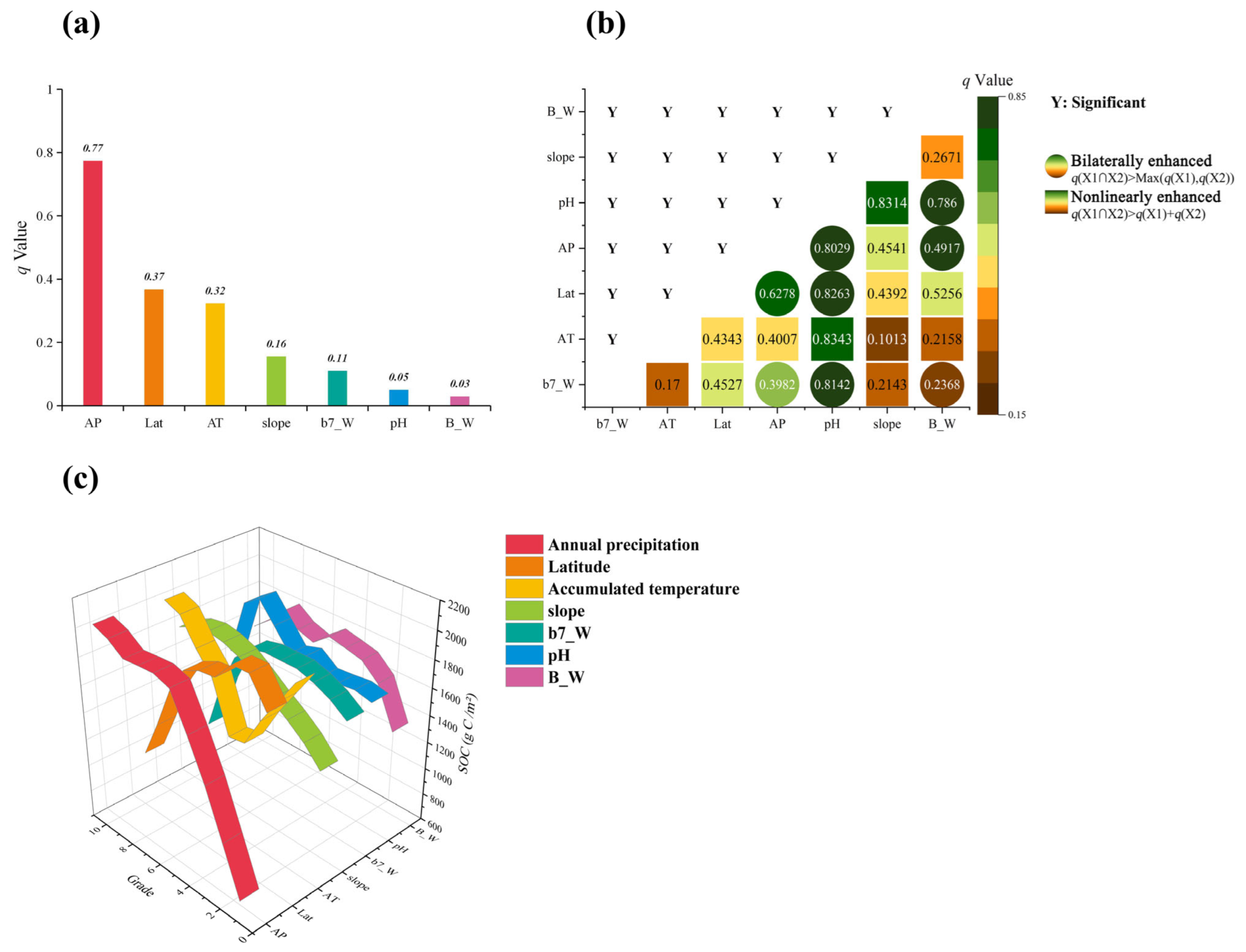

Geographical Detector

3. Results

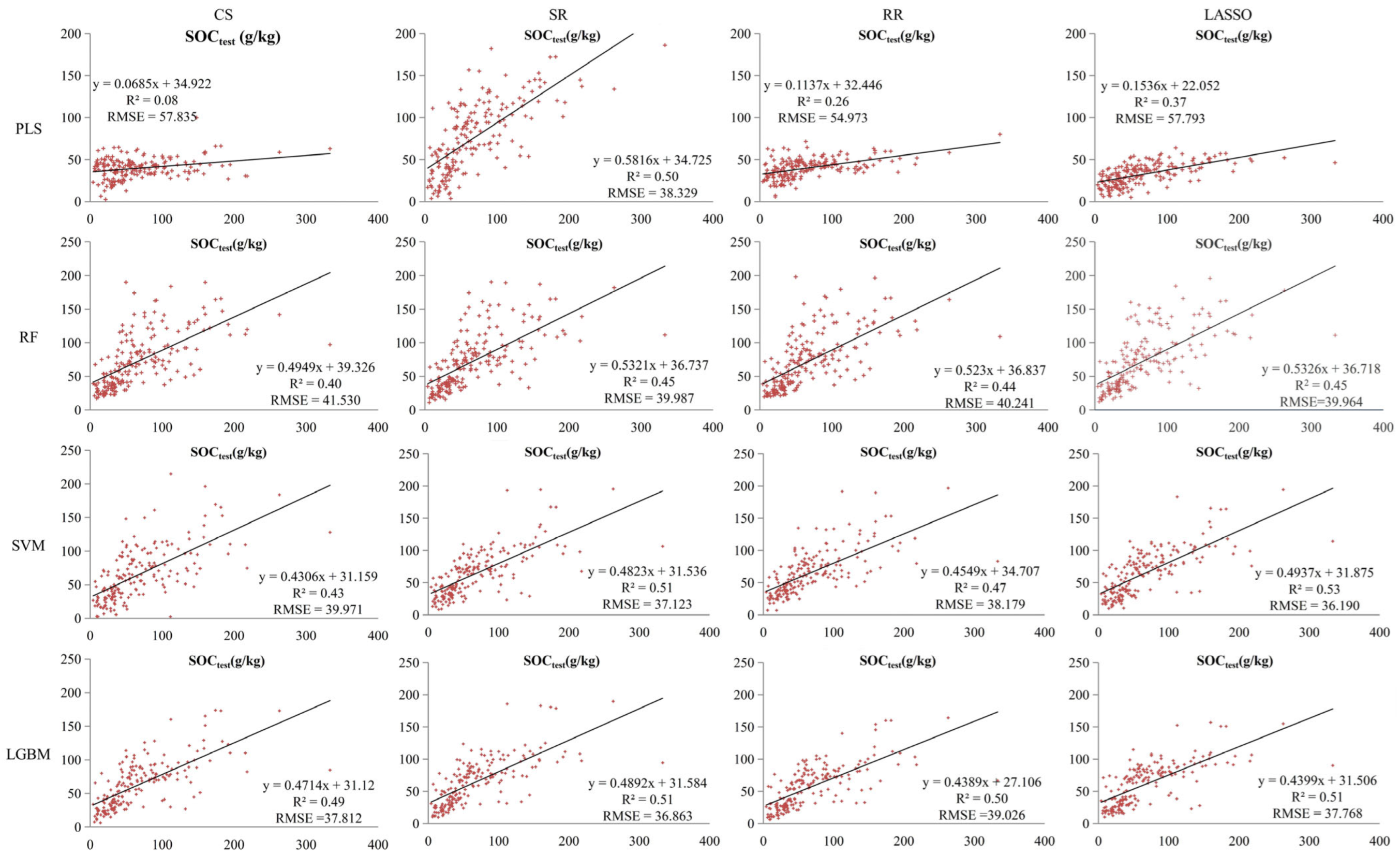

3.1. SOC Estimation Model Performance and Comparison

3.1.1. Correlation and Regression Analysis

3.1.2. Model Performance

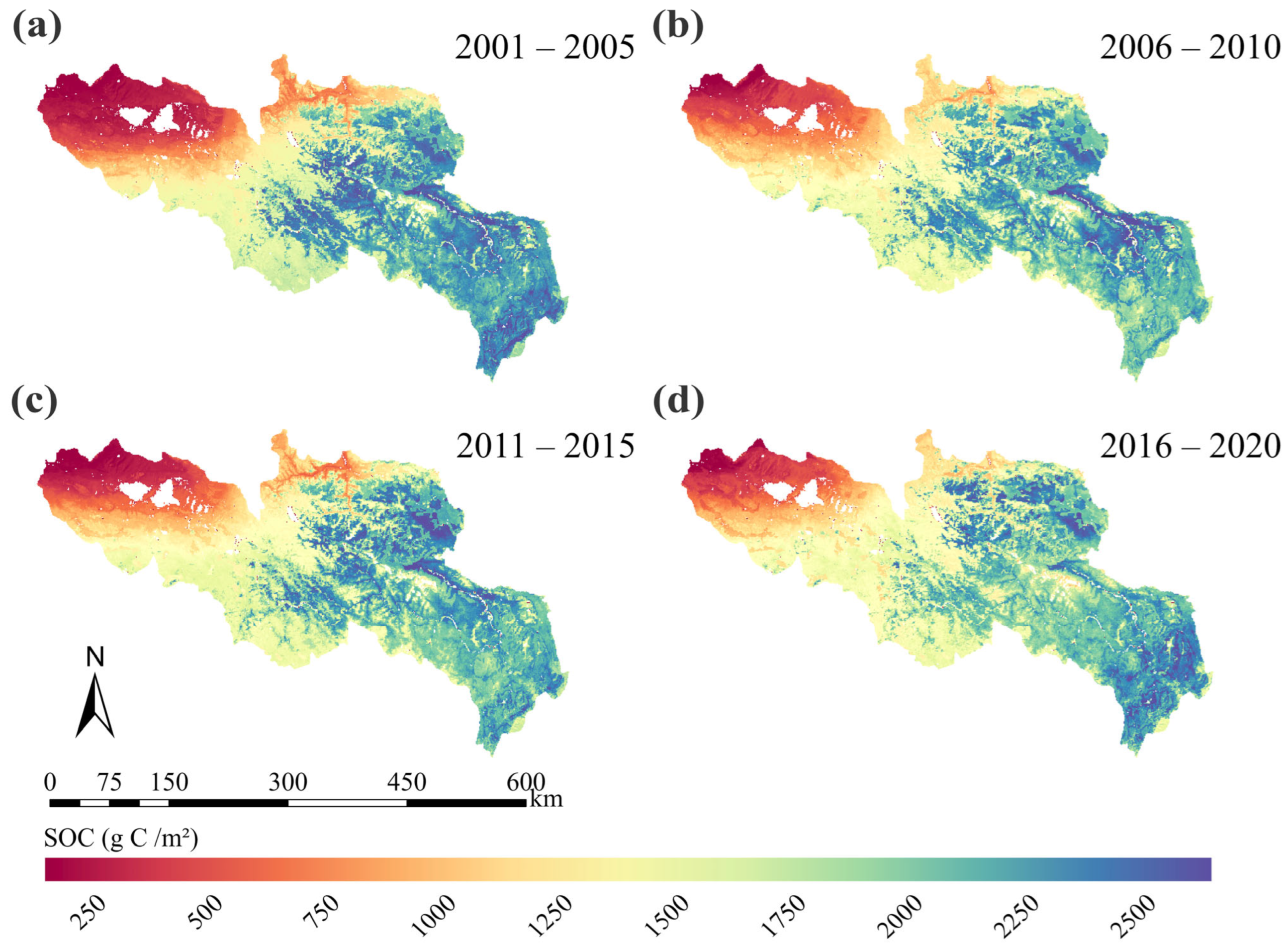

3.2. Spatiotemporal Distribution

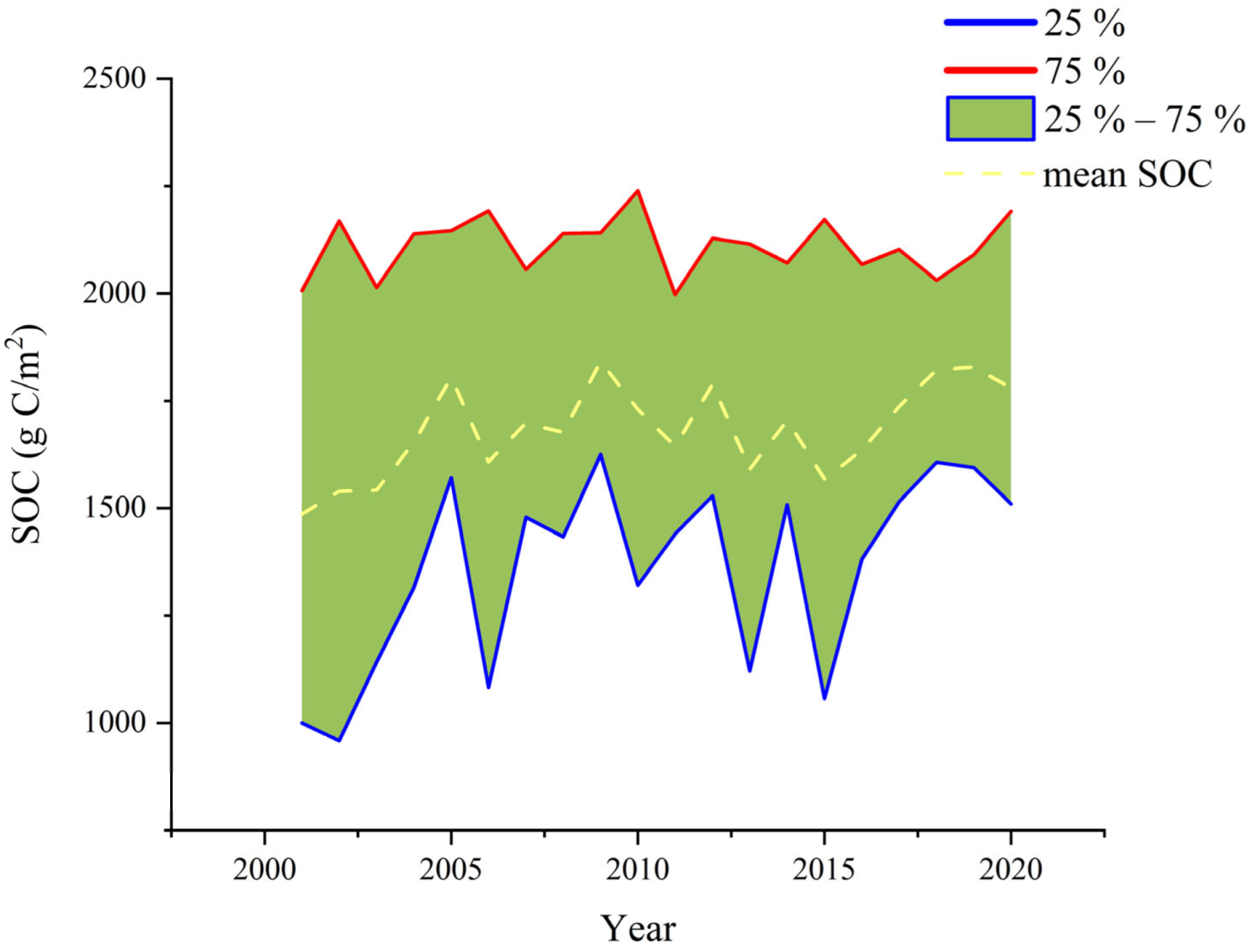

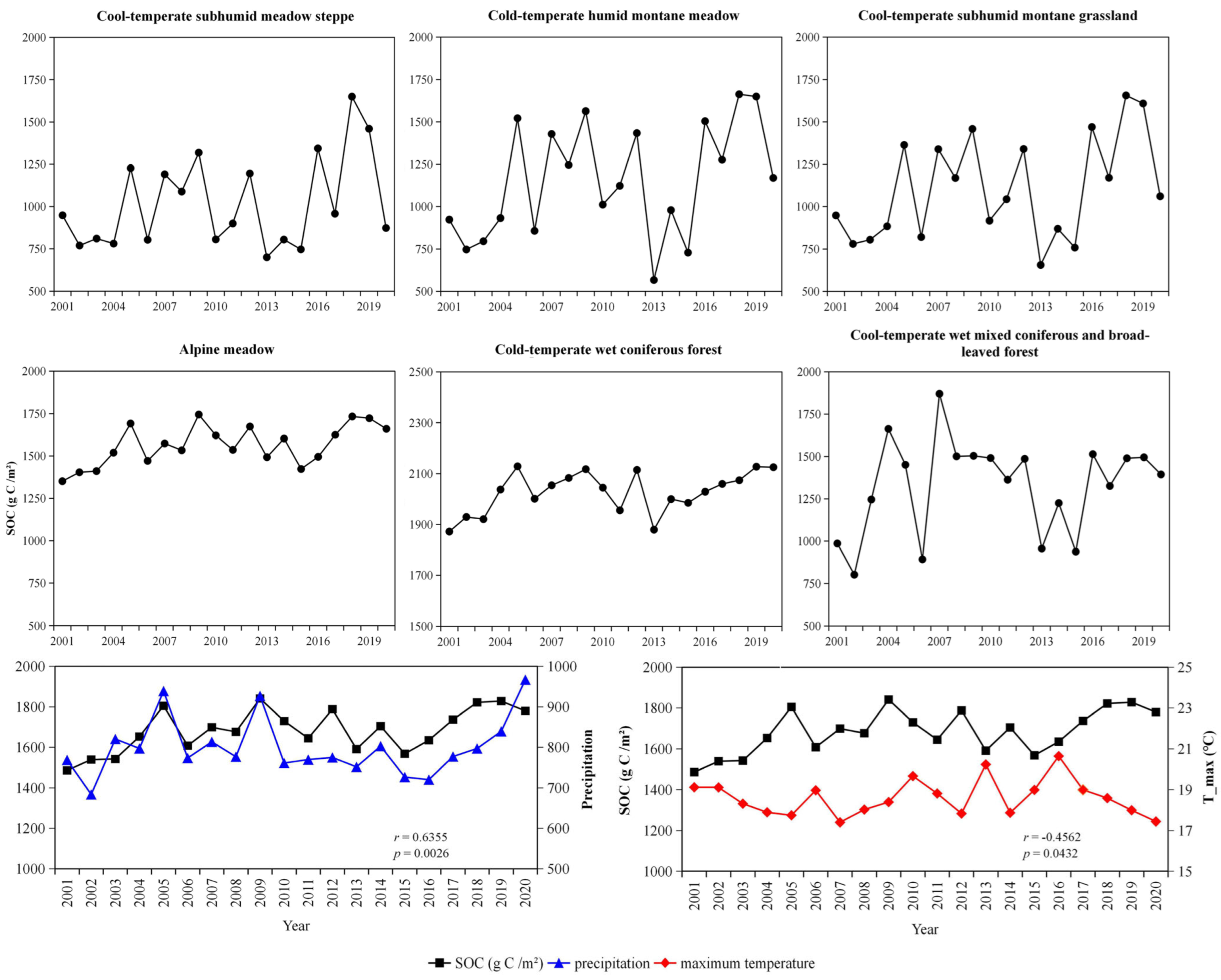

3.2.1. Temporal Characteristics Analysis

3.2.2. Spatial Variability Analysis

3.3. Driving Mechanisms

3.4. Carbon Sequestration Value

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Performance and Comparison

4.2. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics

4.3. Driving Mechanisms Analysis

4.4. Policy Implications: Carbon Sequestration Value

4.5. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Calculation Methods, Data Sources, and Correlation Analysis for SOC and Environmental Variables

| Remote Sensing Indicators | Variable Interpretation | Calculation Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BI | Brightness Index | [168] | |

| CI | Coloration Index | [168] | |

| DVI | Difference Vegetation Index | [169] | |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index | [170] | |

| TVI | Transformed Vegetation Index | [171] | |

| MSAVI | Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index | [172] | |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [171] | |

| RVI | Ratio Vegetation Index | [173] | |

| NDSI | Normalized Difference Soil Index | [174] | |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index | [175] | |

| NDVGI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Green Index | [176] | |

| OSAVI | Optimized Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index | [177] | |

| SCI | Soil Color Index | [178] | |

| SAVI | Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index | [179] | |

| SATVI | Soil-Adjusted Total Vegetation Index | [180] | |

| A | [181] | ||

| B | [181] | ||

| C | [181] | ||

| D | [182] | ||

| E | [181] |

| Variable | Unit | Resolution | Data Sources | Annotation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOC | Soil organic carbon | g/kg | Measured | ||

| Topographic Factors | Longitude (Lon) | – | GPS | Real-time sampling by GPS devices | |

| Latitude (Lat) | – | GPS | Real-time sampling by GPS devices | ||

| Altitude (Alt) | m | 1 km | SRTM 90m DEM Digital Elevation Database (https://srtm.csi.cgiar.org/, accessed on 20 December 2025) | ||

| Aspect (Asp) | ° | 1 km | Calculate from DEM using ArcGIS Pro | ||

| Slope | ° | 1 km | |||

| Climatic Factors | Accumulated temperature (AT) | °C | 1 km | Daily data set of surface climate data in China (https://data.cma.cn/, accessed on 20 December 2025) | ≥0 °C |

| Annual mean temperature (AMT) | °C | 1 km | |||

| Annual precipitation (AP) | mm | 1 km | |||

| LsTD–S | °C | 1 km | MOD11A2 | Daytime ground temperature in summer | |

| LsTD-W | °C | 1 km | Daytime ground temperature in winter | ||

| LsTN-S | °C | 1 km | Ground temperature at night in summer | ||

| LsTN-W | °C | 1 km | Ground temperature at night in winter | ||

| Soil Physicochemical Properties | Clay1 | % | 1 km | Big Data Center of Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions (http://bdc.casnw.net/yyzc/sj/, accessed on 20 December 2025) soil characteristic data set | (0–30 cm) Clay content |

| Clay2 | % | 1 km | (30–100 cm) Clay content | ||

| Sand1 | % | 1 km | (0–30 cm) Sand content | ||

| Sand2 | % | 1 km | (30–100 cm) Clay content | ||

| sand1/clay1 | % | 1 km | (0–30 cm) Soil sand–clay ratio | ||

| snad2/clay2 | % | 1 km | (30–100 cm) Soil sand–clay ratio | ||

| pH | 250 m | SoilGrids250m 2.0 (https://soilgrids.org/, accessed on 20 December 2025) | Soil pH value | ||

| BD | (kg/m3) | 250 m | Bulk density | ||

| Vegetation Factors | NPP | KgC/m2 | 1 km | MOD17A3HGF | Annual net primary productivity |

| EVI | 250 m | MOD13Q1 band calculated | Enhanced vegetation index in summer and winter | ||

| NDVI | 250 m | Normalized vegetation index in summer and winter | |||

| TVI | 250 m | Conversion vegetation index in summer and winter | |||

| BI | 1 km | Brightness index in summer and winter | |||

| DVI | 1 km | Differential vegetation index in summer and winter | |||

| MSAVI | 1 km | Improved soil-adjusted vegetation index in summer and winter | |||

| NDSI | 1 km | Normalized difference soil index in summer and winter | |||

| NDWI | 1 km | Normalized differential water index in summer and winter | |||

| NDVGI | 1 km | Normalized difference vegetation greenness index in summer and winter | |||

| OSAVI | 1 km | Optimal soil-adjusted vegetation index in summer and winter | |||

| RVI | 1 km | Ratio of the vegetation coefficient in summer and winter | |||

| SATVI | 1 km | Soil-adjusted total vegetation index in summer and winter | |||

| SAVI | 1 km | Soil-adjusted vegetation index in summer and winter | |||

| SCI | 1 km | Soil color index in summer and winter | |||

| Remote Sensing Indices | A | 500 m | MOD09A1 dataset | Band in summer and winter | |

| B | 500 m | ||||

| C | 500 m | ||||

| D | 500 m | ||||

| E | 500 m | ||||

| b1 | 500 m | ||||

| b2 | 500 m | ||||

| b3 | 500 m | ||||

| b4 | 500 m | ||||

| b5 | 500 m | ||||

| b6 | 500 m | ||||

| b7 | 500 m | ||||

| Far | 1 km | MOD15A2 dataset | Photosynthetic effective radiation in summer and winter | ||

| Lai | 1 km | Leaf area index in summer and winter | |||

| BLUE | 250 m | MOD13Q1 dataset | Blue band reflectance in winter | ||

| MIR | 250 m | Mid-infrared reflectance in winter | |||

| NIR | 250 m | Near-infrared reflectance in winter | |||

| RED | 250 m | Red band reflectance in winter |

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p Value | Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topographic Factors | Lon | 0.231 ** | 0.00 | Soil Physicochemical Properties | clay1 | 0.126 ** | 0.00 |

| Lat | −0.357 ** | 0.00 | clay2 | 0.177 ** | 0.00 | ||

| Alt | −0.03 | 0.52 | sand1 | −0.03 | 0.54 | ||

| Asp | −0.04 | 0.36 | sand2 | −0.03 | 0.41 | ||

| Slope | −0.04 | 0.33 | sand1/clay1 | 0.04 | 0.38 | ||

| Climatic Factors | AT | −0.294 ** | 0.00 | sand2/clay2 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| AMT | −0.126 ** | 0.00 | pH | −0.244 ** | 0.00 | ||

| AP | 0.222 ** | 0.00 | BL | 0.02 | 0.66 | ||

| LsTD-S | −0.110 ** | 0.01 | |||||

| LsTD-W | −0.105 ** | 0.01 | |||||

| LsTN-S | −0.02 | 0.64 | |||||

| LsTN-W | −0.271 ** | 0.00 |

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p Value | Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPP | 0.094 * | 0.02 | NDWI-S | 0.084 * | 0.04 |

| EVI-S | 0.108 ** | 0.01 | NDWI-W | −0.279 ** | 0.00 |

| EVI-W | 0.05 | 0.23 | NDVGI-S | 0.134 ** | 0.00 |

| NDVI-S | 0.129 ** | 0.00 | NDVGI-W | 0.189 ** | 0.00 |

| NDVI-W | 0.173 ** | 0.00 | OSAVI-S | 0.135 ** | 0.00 |

| TVI-S | 0.129 ** | 0.00 | OSAVI-W | 0.145 ** | 0.00 |

| TVI-W | 0.167 ** | 0.00 | RVI-S | −0.088 * | 0.03 |

| BI-S | 0.150 ** | 0.00 | RVI-W | −0.182 ** | 0.00 |

| BI-W | −0.278 ** | 0.00 | SATVI-S | 0.081 * | 0.04 |

| DVI-S | 0.111 ** | 0.01 | SATVI-W | −0.279 ** | 0.00 |

| DVI–W | 0.06 | 0.13 | SAVI-S | 0.129 ** | 0.00 |

| MSAVI-S | 0.128 ** | 0.00 | SAVI–W | 0.113 ** | 0.01 |

| MSAVI–W | 0.100 ** | 0.01 | SCI-S | 0.079 * | 0.05 |

| NDSI-S | −0.06 | 0.15 | SCI–W | −0.184 ** | 0.00 |

| NDSI–W | 0.086 * | 0.03 |

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p Value | Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A–W | −0.201 ** | 0.00 | b1–W | −0.242 ** | 0.00 |

| A-S | 0.112 ** | 0.01 | b2–W | −0.262 ** | 0.00 |

| B-S | 0.114 ** | 0.00 | b3–W | −0.185 ** | 0.00 |

| B–W | −0.190 ** | 0.00 | b4–W | −0.217 ** | 0.00 |

| C-S | −0.106 ** | 0.01 | b5–W | −0.232 ** | 0.00 |

| C–W | 0.01 | 0.80 | b6–W | −0.08 | 0.05 |

| D-S | −0.101 * | 0.01 | b7–W | −0.372 ** | 0.00 |

| D–W | 0.182 ** | 0.00 | Far-S | 0.141 ** | 0.00 |

| E-S | 0.05 | 0.27 | Far–W | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| E–W | −0.253 ** | 0.00 | Lai-S | 0.144 ** | 0.00 |

| b1-S | –0.03 | 0.39 | Lai–W | 0.082 * | 0.04 |

| b2-S | 0.084 * | 0.04 | BLUE–W | −0.083 * | 0.04 |

| b3-S | 0.06 | 0.15 | MIR–W | −0.120 ** | 0.00 |

| b4-S | 0.02 | 0.64 | NIR–W | −0.162 ** | 0.00 |

| b5-S | 0.08 | 0.06 | RED–W | −0.150 ** | 0.00 |

| b6-S | −0.07 | 0.11 | |||

| b7-S | −0.085 * | 0.03 |

References

- LeCain, D.R.; Morgan, J.A.; Schuman, G.E.; Reeder, J.D.; Hart, R.H. Carbon Exchange and Species Composition of Grazed Pastures and Exclosures in the Shortgrass Steppe of Colorado. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 93, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fang, J. Soil Respiration and Human Effects on Global Grasslands. Glob. Planet. Change 2009, 67, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, J.D.; Schuman, G.E. Influence of Livestock Grazing on C Sequestration in Semi-Arid Mixed-Grass and Short-Grass Rangelands. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 116, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, S.; Ritchie, M.E. Introduced Grazers Can Restrict Potential Soil Carbon Sequestration through Impacts on Plant Community Composition: Soil Carbon and Livestock Production. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, D.S.; Adams, D.E.; Wild, A. Model Estimates of CO2 Emissions from Soil in Response to Global Warming. Nature 1991, 351, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil Carbon Sequestration Impacts on Global Climate Change and Food Security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharlemann, J.P.; Tanner, E.V.; Hiederer, R.; Kapos, V. Global Soil Carbon: Understanding and Managing the Largest Terrestrial Carbon Pool. Carbon Manag. 2014, 5, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Duan, Z. Understanding Alpine Meadow Ecosystems. In Landscape and Ecosystem Diversity, Dynamics and Management in the Yellow River Source Zone; Brierley, G.J., Li, X., Cullum, C., Gao, J., Eds.; Springer Geography; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 117–135. ISBN 978-3-319-30473-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, P.; Chen, S.; Wu, M.; Jia, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, D. Increased Ecosystem Carbon Storage between 2001 and 2019 in the Northeastern Margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Mahanta, S. Carbon Sequestration in Grassland Systems. Range Manag. Agrofor. 2014, 35, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll, T.; Brierley, G.; Yu, G. A Broad Overview of Landscape Diversity of the Yellow River Source Zone. J. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 793–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue, B.; Brierley, G.; Yu, G. Geodiversity in the Yellow River Source Zone. J. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 775–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Lu, T.; Guo, Y.; Ding, X. Impacts of Salinity on the Stability of Soil Organic Carbon in the Croplands of the Yellow River Delta. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Impact of Frozen Soil Changes on Vegetation Phenology in the Source Region of the Yellow River from 2003 to 2015. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020, 141, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Q.; Kang, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, D. Latitudinal Gradient and Environmental Drivers of Soil Organic Carbon in Permafrost Regions of the Headwater Area of the Yellow River. Carb Neutrality 2025, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B. Digital Soil Mapping: A Brief History and Some Lessons. Geoderma 2016, 264, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouladi, N.; Møller, A.B.; Tabatabai, S.; Greve, M.H. Mapping Soil Organic Matter Contents at Field Level with Cubist, Random Forest and Kriging. Geoderma 2019, 342, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadoux, A.M.J.-C.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B. Machine Learning for Digital Soil Mapping: Applications, Challenges and Suggested Solutions. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 210, 103359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-M.; Zhang, G.-L.; Liu, F.; Lu, Y.-Y.; Yang, F.; Yang, F.; Yang, M.; Zhao, Y.-G.; Li, D.-C. Comparison of Boosted Regression Tree and Random Forest Models for Mapping Topsoil Organic Carbon Concentration in an Alpine Ecosystem. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Were, K.; Bui, D.T.; Dick, Ø.B.; Singh, B.R. A Comparative Assessment of Support Vector Regression, Artificial Neural Networks, and Random Forests for Predicting and Mapping Soil Organic Carbon Stocks across an Afromontane Landscape. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Lal, R.; Liu, D. A Geographically Weighted Regression Kriging Approach for Mapping Soil Organic Carbon Stock. Geoderma 2012, 189, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballabio, C.; Panagos, P.; Montanarella, L. Predicting Soil Organic Carbon Content in Cyprus Using Remote Sensing and Earth Observation Data. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment (RSCy2014), Paphos, Cyprus, 7–10 April 2014; Hadjimitsis, D.G., Themistocleous, K., Michaelides, S., Papadavid, G., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9229, pp. 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.; Sheng, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, R.; Ding, S.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Using Machine Learning Algorithms Based on GF-6 and Google Earth Engine to Predict and Map the Spatial Distribution of Soil Organic Matter Content. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziachris, P.; Aschonitis, V.; Chatzistathis, T.; Papadopoulou, M. Assessment of Spatial Hybrid Methods for Predicting Soil Organic Matter Using DEM Derivatives and Soil Parameters. CATENA 2019, 174, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, E.S.; Baldock, J.A.; Skjemstad, J.O. Importance of Mechanisms and Processes of the Stabilisation of Soil Organic Matter for Modelling Carbon Turnover. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-X.; Pan, J.-J. Dynamics Models of Soil Organic Carbon. J. For. Res. 2003, 14, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Ping, L.; Wong, M. Systematic Relationship between Soil Properties and Organic Carbon Mineralization Based on Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Fang, J.; Ciais, P.; Peylin, P.; Huang, Y.; Sitch, S.; Wang, T. The Carbon Balance of Terrestrial Ecosystems in China. Nature 2009, 458, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batlle-Aguilar, J.; Brovelli, A.; Porporato, A.; Barry, D.A. Modelling Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles during Land Use Change. In Sustainable Agriculture Volume 2; Lichtfouse, E., Hamelin, M., Navarrete, M., Debaeke, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 499–527. ISBN 978-94-007-0393-3. [Google Scholar]

- Stockmann, U.; Adams, M.A.; Crawford, J.W.; Field, D.J.; Henakaarchchi, N.; Jenkins, M.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Courcelles, V.D.R.D.; Singh, K.; et al. The Knowns, Known Unknowns and Unknowns of Sequestration of Soil Organic Carbon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 164, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R.S. Soil Resources Mapping: A Remote Sensing Perspective. Remote Sens. Rev. 2001, 20, 89–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, N.M.; Grunwald, S.; McDowell, M.L.; Bruland, G.L.; Myers, D.B.; Harris, W.G. Modelling Soil Carbon Fractions with Visible Near-Infrared (VNIR) and Mid-Infrared (MIR) Spectroscopy. Geoderma 2015, 239–240, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, W.; King, A.; Wullschleger, S. Soil Organic Matter Models and Global Estimates of Soil Organic Carbon. In Evaluation of Soil Organic Matter Models: Using Existing Long-Term Datasets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.-M.; Huang, L.-M.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, C.-M.; Xu, L. Mapping the Distribution, Trends, and Drivers of Soil Organic Carbon in China from 1982 to 2019. Geoderma 2023, 429, 116232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shen, F.; Li, X.; Cui, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Zhou, C. Spatio-Temporal Mapping Reveals Changes in Soil Organic Carbon Stocks across the Contiguous United States since 1955. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorji, T.; Odeh, I.O.; Field, D.J.; Baillie, I.C. Digital Soil Mapping of Soil Organic Carbon Stocks under Different Land Use and Land Cover Types in Montane Ecosystems, Eastern Himalayas. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 318, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Hartemink, A.E.; Minasny, B.; Bou Kheir, R.; Greve, M.B.; Greve, M.H. Digital Mapping of Soil Organic Carbon Contents and Stocks in Denmark. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Nabiollahi, K.; Kerry, R. Digital Mapping of Soil Organic Carbon at Multiple Depths Using Different Data Mining Techniques in Baneh Region, Iran. Geoderma 2016, 266, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivas, K.; Dadhwal, V.; Kumar, S.; Harsha, G.S.; Mitran, T.; Sujatha, G.; Suresh, G.J.R.; Fyzee, M.; Ravisankar, T. Digital Mapping of Soil Organic and Inorganic Carbon Status in India. Geoderma 2016, 269, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Kwon, S.-I.; Kim, S.-H.; Shim, J.; Lee, Y.-H.; Oh, T.-K. Estimation of Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) Stock in South Korea Using Digital Soil Mapping Technique. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2021, 54, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, R.; Karunaratne, S.; Lessels, J.; Yogenthiran, N.; Rajapaksha, R.; Gnanavelrajah, N. Digital Soil Mapping of Organic Carbon Concentration in Paddy Growing Soils of Northern Sri Lanka. Geoderma Reg. 2016, 7, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, R.; Behrens, T.; Märker, M.; Elsenbeer, H. Soil Organic Carbon Concentrations and Stocks on Barro Colorado Island—Digital Soil Mapping Using Random Forests Analysis. Geoderma 2008, 146, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siewert, M.B. High-Resolution Digital Mapping of Soil Organic Carbon in Permafrost Terrain Using Machine Learning: A Case Study in a Sub-Arctic Peatland Environment. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 1663–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Qin, Y.; Deo, R.C.; Zhang, C. Effects of Topography on Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in Grasslands of a Semiarid Alpine Region, Northwestern China. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.P.; Wattenbach, M.; Smith, P.; Meersmans, J.; Jolivet, C.; Boulonne, L.; Arrouays, D. Spatial Distribution of Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in France. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, G.S.; Shit, P.K.; Maiti, R. Comparison of GIS-Based Interpolation Methods for Spatial Distribution of Soil Organic Carbon (SOC). J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Bai, X.; Yao, W.; Li, P.; Hu, J.; Kang, L. Spatioemporal Dynamics and Driving Forces of Soil Organic Carbon Changes in an Arid Coal Mining Area of China Investigated Based on Remote Sensing Techniques. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Qian, J.; Zhao, R.; Yang, Q.; Wu, K.; Zhao, H.; Feng, Z.; Dong, J. Spatio-Temporal Variation and Its Driving Forces of Soil Organic Carbon along an Urban–Rural Gradient: A Case Study of Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geremew, B.; Tadesse, T.; Bedadi, B.; Gollany, H.T.; Tesfaye, K.; Aschalew, A. Impact of Land Use/Cover Change and Slope Gradient on Soil Organic Carbon Stock in Anjeni Watershed, Northwest Ethiopia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Yang, J.; Dong, S.; He, F.; Zhang, Y. The Influence of Grazing Intensity on Soil Organic Carbon Storage in Grassland of China: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Chen, H.; Ma, Z.; Huang, C.; Wu, X.; Chang, S.X.; Tavakkoli, E.; Cai, Y. New Insights into the Relationships between Livestock Grazing Behaviors and Soil Organic Carbon Stock in an Alpine Grassland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 355, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, W.; Cao, W.; Wang, S. Effects of Different Intensities of Long-Term Grazing on Plant Diversity, Biomass and Carbon Stock in Alpine Shrubland on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; McConnell, C.; Coleman, K.; Cox, P.; Falloon, P.; Jenkinson, D.; Powlson, D. Global Climate Change and Soil Carbon Stocks; Predictions from Two Contrasting Models for the Turnover of Organic Carbon in Soil. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B. Temperature Effects on Soil Organic Carbon, Soil Labile Organic Carbon Fractions, and Soil Enzyme Activities under Long-Term Fertilization Regimes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 102, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Li, G.; Yan, L.; Liu, S. Effects of Extreme Rainfall Frequency on Soil Organic Carbon Fractions and Carbon Pool in a Wet Meadow on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Feng, Q.; Qin, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Deo, R.C.; Zhang, C.; Li, R.; Li, B. The Role of Topography in Shaping the Spatial Patterns of Soil Organic Carbon. Catena 2019, 176, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangroo, S.; Najar, G.; Rasool, A. Effect of Altitude and Aspect on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in the Himalayan Mawer Forest Range. Catena 2017, 158, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lan, Z.; Li, H.; Jaffar, M.T.; Li, X.; Cui, L.; Han, J. Coupling Effects of Soil Organic Carbon and Moisture under Different Land Use Types, Seasons and Slope Positions in the Loess Plateau. Catena 2023, 233, 107520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błońska, E.; Lasota, J. Soil Organic Matter Accumulation and Carbon Fractions along a Moisture Gradient of Forest Soils. Forests 2017, 8, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Li, F.Y.; Jaesong, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, T.; Liu, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y. Soil Water Retention Capacity Surpasses Climate Humidity in Determining Soil Organic Carbon Content but Not Plant Production in the Steppe Zone of Northern China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Pan, J.; Fan, Z.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y. Soil Organic Carbon Distribution in Relation to Terrain & Land Use—A Case Study in a Small Watershed of Danjiangkou Reservoir Area, China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 20, e00731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Peng, M.; Yang, Z.; Yang, K.; Zhao, C.; Li, K.; Guo, F.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, H. Spatial Distribution and Driving Factors of Soil Organic Carbon in the Northeast China Plain: Insights from Latest Monitoring Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 911, 168602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Tan, Z. Quantitative Attribution of Major Driving Forces on Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2015, 7, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwal, J.; Nath, A.; Brahma, B.; Deb, S.; Sahoo, U.K.; Nath, A.J. Patterns and Driving Factors of Biomass Carbon and Soil Organic Carbon Stock in the Indian Himalayan Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 145292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzehpour, N.; Shafizadeh-Moghadam, H.; Valavi, R. Exploring the Driving Forces and Digital Mapping of Soil Organic Carbon Using Remote Sensing and Soil Texture. Catena 2019, 182, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Sun, K.; Jin, J.; Xing, B. Some Concepts of Soil Organic Carbon Characteristics and Mineral Interaction from a Review of Literature. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 94, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungkunst, H.F.; Göpel, J.; Horvath, T.; Ott, S.; Brunn, M. Global Soil Organic Carbon–Climate Interactions: Why Scales Matter. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2022, 13, e780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Yang, C.; Wu, T.; Zhai, Y.; Tian, S.; Feng, Y. Analysis of Vegetation Coverage Changes and Driving Forces in the Source Region of the Yellow River. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Wu, F.; Yang, Z. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Temperature Trends under Climate Change in the Source Region of the Yellow River, China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015, 119, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Berndtsson, R.; Zhang, L.; Uvo, C.B.; Hao, Z.; Wang, X.; Yasuda, H. Hydro Climatic Trend and Periodicity for the Source Region of the Yellow River. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2015, 20, 05015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhao, Y. Soil Erosion Assessment of Alpine Grassland in the Source Park of the Yellow River on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 9, 771439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-T.; Hu, X.-S.; Li, X.-L.; Zhao, J.-M.; Xing, G.-Y.; Liu, C.-Y. Impact of Meadow Degradations on the Probabilistic Distribution Patterns of Physical and Mechanical Indices of Rooted Soil in the Upper Regions of the Yellow River, China. Water 2024, 16, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W. Three-River-Source National Park System Pilot Area’s Steps toward Cohesive Conservation and Management. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2020, 8, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Feng, Q.; Huang, X.; Ren, J. Review in the Study of Comprehensive Sequential Classification System of Grassland. Acta Prataculturae Sinica 2011, 20, 252–258, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Worsham, L.; Markewitz, D.; Nibbelink, N.P.; West, L.T. A Comparison of Three Field Sampling Methods to Estimate Soil Carbon Content. For. Sci. 2012, 58, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B. A Conditioned Latin Hypercube Method for Sampling in the Presence of Ancillary Information. Comput. Geosci. 2006, 32, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, X.; Shi, J.; Shen, F.; Qi, F.; Gao, B.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, A.-X.; Zhou, C. Evaluation of Conditioned Latin Hypercube Sampling for Soil Mapping Based on a Machine Learning Method. Geoderma 2020, 369, 114337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerenfes, D.; Giorgis, A.; Negasa, G. Comparison of Organic Matter Determination Methods in Soil by Loss on Ignition and Potassium Dichromate Method. Int. J. Hortic. Food Sci. 2022, 4, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavatta, C.; Antisari, L.V.; Sequi, P. Determination of Organic Carbon in Soils and Fertilizers. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1989, 20, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, S.; Martínez-Peña, R.; Castrillo, D. Beyond Vegetation: A Review Unveiling Additional Insights into Agriculture and Forestry through the Application of Vegetation Indices. J 2023, 6, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Sun, Z.; Di, L. Characteristics of Vegetation Response to Drought in the CONUS Based on Long-Term Remote Sensing and Meteorological Data. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Applications. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, W.; Dai, Y. A China Soil Characteristics Dataset (2010); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Sun, W. A China Dataset of Soil Properties for Land Surface Modeling (Version 2, CSDLv2); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, L. Tests of Significance in Stepwise Regression. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efroymson, M. Stepwise Regression—A Backward and Forward Look; Eastern Regional Meetings of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics: Florham Park, NJ, USA, 1966; pp. 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T. Ridge Regularization: An Essential Concept in Data Science. Technometrics 2020, 62, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warton, D.I. Penalized Normal Likelihood and Ridge Regularization of Correlation and Covariance Matrices. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2008, 103, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranstam, J.; Cook, J.A. LASSO Regression. J. Br. Surg. 2018, 105, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H. Partial Least Squares Regression and Projection on Latent Structure Regression (PLS Regression). Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H. Partial Least Square Regression (PLS Regression). Encycl. Res. Methods Soc. Sci. 2003, 6, 792–795. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigatti, S.J. Random Forest. J. Insur. Med. 2017, 47, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burges, C.J. A Tutorial on Support Vector Machines for Pattern Recognition. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 1998, 2, 121–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakkula, V. Tutorial on Support Vector Machine (Svm); School of EECS, Washington State University: Pullman, WA, USA, 2006; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. Lightgbm: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric Tests against Trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Charles Griffin & Company: London, UK, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.-F.; Li, X.-H.; Christakos, G.; Liao, Y.-L.; Zhang, T.; Gu, X.; Zheng, X.-Y. Geographical Detectors-Based Health Risk Assessment and Its Application in the Neural Tube Defects Study of the Heshun Region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N.H. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus, W. A Review of the Stern Review on the Economics of Global Warming. J. Econ. Lit. 2007, 45, 686–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tol, R.S. The Marginal Damage Costs of Carbon Dioxide Emissions: An Assessment of the Uncertainties. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.P.; Arif, M.; Al Mamun, A.; Mahmud, F.; Rahman, T.; Ahmmed, M.J.; Mou, S.N.; Akter, P.; Chowdhury, M.S.R.; Uddin, M.K. A Comparative Study of Machine Learning Models for Predicting Customer Churn in Retail Banking: Insights from Logistic Regression, Random Forest, GBM, and SVM. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2024, 6, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.; Li, E.; Fissha, Y.; Zhou, J.; Segarra, P. LGBM-Based Modeling Scenarios to Compressive Strength of Recycled Aggregate Concrete with SHAP Analysis. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 5999–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibindi, R.; Mwangi, R.W.; Waititu, A.G. A Boosting Ensemble Learning Based Hybrid Light Gradient Boosting Machine and Extreme Gradient Boosting Model for Predicting House Prices. Eng. Rep. 2023, 5, e12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effrosynidis, D.; Arampatzis, A. An Evaluation of Feature Selection Methods for Environmental Data. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 61, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, R.; Rohini, R. LASSO: A Feature Selection Technique in Predictive Modeling for Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Advances in Computer Applications (ICACA), Coimbatore, India, 24 October 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, A.; Rad, A.K.; Nematollahi, M.J.; Mahmoudi, M. Application of the Lasso Regularisation Technique in Mitigating Overfitting in Air Quality Prediction Models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liang, W.; Awada, T.; Hiller, J.; Kaiser, M. Machine Learning for Modeling Soil Organic Carbon as Affected by Land Cover Change in the Nebraska Sandhills, USA. Environ. Model. Assess. 2024, 29, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, T.; Zhao, L.; Li, R.; Li, W.; Hu, G.; Zou, D.; Ni, J.; Du, Y.; et al. Soil Texture and Its Relationship with Environmental Factors on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ni, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, G.; Luo, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S. Spatial-Temporal Evolution and Driving Forces of Drying Trends on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Based on Geomorphological Division. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Z.; Qin, Y.; Yu, X. Spatial Variability in Soil Organic Carbon and Its Influencing Factors in a Hilly Watershed of the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2016, 137, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Feng, W.; Luo, Y.; Baldock, J.; Wang, E. Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics Jointly Controlled by Climate, Carbon Inputs, Soil Properties and Soil Carbon Fractions. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 4430–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canero, F.M.; Rodriguez-Galiano, V.; Aragones, D. Machine Learning and Feature Selection for Soil Spectroscopy. An Evaluation of Random Forest Wrappers to Predict Soil Organic Matter, Clay, and Carbonates. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Schmidt, K.; Amirian-Chakan, A.; Rentschler, T.; Zeraatpisheh, M.; Sarmadian, F.; Valavi, R.; Davatgar, N.; Behrens, T.; Scholten, T. Improving the Spatial Prediction of Soil Organic Carbon Content in Two Contrasting Climatic Regions by Stacking Machine Learning Models and Rescanning Covariate Space. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; He, N. Soil Organic Carbon Contents, Aggregate Stability, and Humic Acid Composition in Different Alpine Grasslands in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 2015–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, H.; Dong, S.; Zhao, S.; Beazley, R. The Spatio-Temporal Patterns of the Topsoil Organic Carbon Density and Its Influencing Factors Based on Different Estimation Models in the Grassland of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M.U.F. Will Changes in Soil Organic Carbon Act as a Positive or Negative Feedback on Global Warming? Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Variation of Soil Organic Carbon Components and Enzyme Activities during the Ecological Restoration in a Temperate Forest. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 201, 107192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurmu, G. Soil Organic Matter and Its Role in Soil Health and Crop Productivity Improvement. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 7, 475–483. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xia, Y.; Tan, X.; Gan, F.; Jiang, L.; Xu, X.; Yan, Y.; Fan, Y.; Pu, J. Does the Returning Farmland to Grassland (Retiring Grassland) Improve the Soil Aggregate Stability in Erosion and Deposition Sites? Catena 2025, 255, 109023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, P.; Zhan, X.; Han, J.; Guo, M.; Wang, F. Warming and Increasing Precipitation Induced Greening on the Northern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Catena 2023, 233, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Tang, H. Evidence of Warming and Wetting Climate over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2010, 42, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zu, J.; Zhang, J. The Influences of Climate Change and Human Activities on Vegetation Dynamics in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, T.; Xiao, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, W.; Du, Z.; Huang, L.; Yue, T. Grassland Productivity Increase Was Dominated by Climate in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from 1982 to 2020. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Tao, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Shi, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, C. The Impact of Climate Change and Anthropogenic Activities on Alpine Grassland over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 189, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Du, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lin, L.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Cao, G. Distribution of Soil Carbon in Different Grassland Types of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 1806–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Wang, D.; Ren, L.; Du, Y.; Zhou, G. Storage and Controlling Factors of Soil Organic Carbon in Alpine Wetlands and Meadow across the Tibetan Plateau. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2023, 74, e13383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Li, G.; Yan, L.; Wei, X. Effects of Rainfall Frequency on Soil Labile Carbon Fractions in a Wet Meadow on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Soils Sediments 2022, 22, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.-R.M.; Ma, W.; Li, G.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, J.; Chen, G. Response of Soil Organic Carbon to Vegetation Degradation along a Moisture Gradient in a Wet Meadow on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 11999–12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Cheng, Y.; Jian, J.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, C.; Li, J.; Chen, T. Water Erosion Changes on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and Its Response to Climate Variability and Human Activities during 1982–2015. Catena 2023, 229, 107207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Du, J.; Bahadur, A.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Wu, T.; Chen, S. Soil Erosion and Risk Assessment on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-H.; Chen, S.-Y.; Chen, J.-W.; Xue, K.; Chen, S.-L.; Wang, X.-M.; Chen, T.; Kang, S.-C.; Rui, J.-P.; Thies, J.E.; et al. Reduced Microbial Stability in the Active Layer Is Associated with Carbon Loss under Alpine Permafrost Degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2025321118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gu, Y.; Liu, E.; Wu, M.; Cheng, X.; Yang, P.; Bahadur, A.; Bai, R.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; et al. Freeze-Thaw Strength Increases Microbial Stability to Enhance Diversity-Soil Multifunctionality Relationship. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Yu, W.; Dutta, S.; Gao, H. Soil Microbial Community Composition and Function Are Closely Associated with Soil Organic Matter Chemistry along a Latitudinal Gradient. Geoderma 2021, 383, 114744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, C.; Wang, X.; Song, Y. Changes in Labile Soil Organic Carbon Fractions in Wetland Ecosystems along a Latitudinal Gradient in Northeast China. Catena 2012, 96, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Z. Globally Altitudinal Trends in Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Storages. Catena 2022, 210, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraka, T.; Elias, E.; Lelago, A. Soil Organic Carbon and Its’ Stock Potential in Different Land-Use Types along Slope Position in Coka Watershed, Southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.C.; McCarty, G.W.; Venteris, E.R.; Kaspar, T. Soil and Soil Organic Carbon Redistribution on the Landscape. Geomorphology 2007, 89, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifeld, J.; Zimmermann, M.; Fuhrer, J. Simulating Decomposition of Labile Soil Organic Carbon: Effects of pH. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 2948–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Puissant, J.; Buckeridge, K.M.; Goodall, T.; Jehmlich, N.; Chowdhury, S.; Gweon, H.S.; Peyton, J.M.; Mason, K.E.; van Agtmaal, M.; et al. Land Use Driven Change in Soil pH Affects Microbial Carbon Cycling Processes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, A.; Jones, C.; Jacobsen, J. Soil pH and Organic Matter. Nutr. Manag. Modul. 2009, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov, Y. Priming Effects: Interactions between Living and Dead Organic Matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Balser, T.C. Microbial Production of Recalcitrant Organic Matter in Global Soils: Implications for Productivity and Climate Policy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontaine, S.; Barot, S.; Barré, P.; Bdioui, N.; Mary, B.; Rumpel, C. Stability of Organic Carbon in Deep Soil Layers Controlled by Fresh Carbon Supply. Nature 2007, 450, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholes, M.C.; Powlson, D.; Tian, G. Input Control of Organic Matter Dynamics. Geoderma 1997, 79, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, W.; Xue, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Hu, R.; Zeng, H.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; et al. Grassland Changes and Adaptive Management on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.B. Rangeland Degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: A Review of the Evidence of Its Magnitude and Causes. J. Arid Environ. 2010, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, D.P.; Miller, D.; Johnson, D.A. Transformation of Traditional Pastoral Livestock Systems on the Tibetan Steppe. Sci. Et Chang. Planétaires/Sécheresse 2006, 17, 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Mao, Z.; Tang, Q.; Liu, J.; Xu, J. Projected Humidification Expands the Sustainable Grazing Areas in the Drylands of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2024, 10, 0284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Sun, Z.; Lu, Q.; Gao, W.; Bai, Y. Effects of Seasonal Rest Grazing on Soil Aggregate Stability and Organic Carbon in Alpine Grasslands in Northern Xizang. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 3350–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z. Geographical Features of Agricultural Technology in the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet) Plateau in the Qing Dynasty. In Environment and Selection of Technology: The Historical Agrotechnical Geography of West China During the Qing Dynasty; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tomelleri, E. others Modeling the Carbon Cycle and Its Interactions with Management Practices in Grasslands. 2007. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11577/3426898 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Duan, H.; Xue, X.; Wang, T.; Kang, W.; Liao, J.; Liu, S. Spatial and Temporal Differences in Alpine Meadow, Alpine Steppe and All Vegetation of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and Their Responses to Climate Change. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A. The Extent and Value of Carbon Stored in Mountain Grasslands and Shrublands Globally, and the Prospects for Using Climate Finance to Address Natural Resource Management Issues. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, F.; Du, Y.; Guo, X.; Lin, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Cao, G. Ecosystem Carbon Storage in Alpine Grassland on the Qinghai Plateau. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J. Carbon Storage in Grasslands of China. J. Arid Environ. 2002, 50, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhong, H.; Harris, W.; Yu, G.; Wang, S.; Hu, Z.; Yue, Y. Carbon Storage in the Grasslands of China Based on Field Measurements of Above-and below-Ground Biomass. Clim. Change 2008, 86, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, L.L.; Possingham, H.P.; Carwardine, J.; Klein, C.J.; Roxburgh, S.H.; Russell-Smith, J.; Wilson, K.A. The Effect of Carbon Credits on Savanna Land Management and Priorities for Biodiversity Conservation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Dang, D.; Dou, H.; Lou, A. Strengthening Grassland Carbon Source and Sink Management to Enhance Its Contribution to Regional Carbon Neutrality. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 152, 110341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Brown, C.; Qiao, G.; Zhang, B. Effect of Eco-Compensation Schemes on Household Income Structures and Herder Satisfaction: Lessons from the Grassland Ecosystem Subsidy and Award Scheme in Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Swallow, B.; Foggin, J.M.; Zhong, L.; Sang, W. Co-Management for Sustainable Development and Conservation in Sanjiangyuan National Park and the Surrounding Tibetan Nomadic Pastoralist Areas. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, A.; Wang, S.; Lipper, L.; Chang, X. Market Costs and Financing Options for Grassland Carbon Sequestration: Empirical and Modelling Evidence from Qinghai, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 657608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Lee, T.M.; Nie, X.; Wang, T.; Liang, E.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Piao, S.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions Can Help Restore Degraded Grasslands and Increase Carbon Sequestration in the Tibetan Plateau. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, T.; Ellis, J.; He, F.; Hu, L.; Li, Q. Rewilding the Wildlife in Sangjiangyuan National Park, Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020, 6, 1776643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Shang, Z.; Gao, J.; Boone, R.B. Enhancing Sustainability of Grassland Ecosystems through Ecological Restoration and Grazing Management in an Era of Climate Change on Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 287, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirchooli, F.; Kiani-Harchegani, M.; Khaledi Darvishan, A.; Falahatkar, S.; Sadeghi, S.H. Spatial Distribution Dependency of Soil Organic Carbon Content to Important Environmental Variables. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 116, 106473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yang, X.; Qiu, J.; Li, J.; Gao, T.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, F.; Ma, H.; Yu, H.; Xu, B. Remote Sensing-Based Biomass Estimation and Its Spatio-Temporal Variations in Temperate Grassland, Northern China. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 1496–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deering, D. Measuring Forage Production of Grazing Units from Landsat MSS Data. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 6–10 October 1975; ERIM: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1975; pp. 1169–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.D.; Huete, A.R. Interpreting Vegetation Indices. Prev. Vet. Med. 1991, 11, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, M.; Chen, R. RNDSI: A Ratio Normalized Difference Soil Index for Remote Sensing of Urban/Suburban Environments. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2015, 39, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzzo, L.; Puleo, V.; Nizza, S.; Freni, G. Parameterization of a Bayesian Normalized Difference Water Index for Surface Water Detection. Geosciences 2020, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a Green Channel in Remote Sensing of Global Vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, M.D. The Sensitivity of the OSAVI Vegetation Index to Observational Parameters. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 63, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Kheir, R.; Greve, M.H.; Bøcher, P.K.; Greve, M.B.; Larsen, R.; McCloy, K. Predictive Mapping of Soil Organic Carbon in Wet Cultivated Lands Using Classification-Tree Based Models: The Case Study of Denmark. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1150–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsett, R.C.; Qi, J.; Heilman, P.; Biedenbender, S.H.; Carolyn Watson, M.; Amer, S.; Weltz, M.; Goodrich, D.; Marsett, R. Remote Sensing for Grassland Management in the Arid Southwest. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 59, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, D.C.; Kergoat, L.; Hiernaux, P.; Mougin, E.; Defourny, P. Monitoring Dry Vegetation Masses in Semi-Arid Areas with MODIS SWIR Bands. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 153, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Yang, S.; Feng, Q.; Liu, B.; Zhang, R.; Huang, X.; Xie, H. Multi-Factor Modeling of above-Ground Biomass in Alpine Grassland: A Case Study in the Three-River Headwaters Region, China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 186, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Meteorological Factors | Topographic Factor | Soil Factors | Vegetation Indices | Remote Sensing Bands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR | AT, AP | Lat, Slope | pH | NDSI-S | b2-S, b6-W, b7-W, MIR-W, A-W, B-W, E-S |

| RR | AT, AP, LsTD-S, LsTN-S, LsTN-W | long, Lat, Alt, Slope | clay1, clay2, sand2, pH | EVI-W, BI-W, NDSI-S, NDWI-W, RVI-W, SCI-W | B-W, E-S, E-W, D-W, b6-S, b7-S, b1-W, b2-W, b4-W, b7-W, BLUE-W |

| LASSO | AT, AP, LsTD-S | Lat, Slope | clay2, pH | B-W, E-W, D-W, b6-W, b7-W |

| Trend | h | p Value | Tau | Sen’s Slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| increasing | True | 0. 018 | 0. 389 | 11.685 |

| Grassland Type | Grassland Area (km2) | MIN | MAX | MEAN | STD | SUM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/kg) | (g C/m2) | (g/kg) | (g C/m2) | (g/kg) | (g C/m2) | (g/kg) | (g C/m2) | (g/kg × 103) | (g C/m2 × 106) | ||

| Cool temperate subhumid meadow steppe | 25.0 | 39.0 | 945.0 | 56.1 | 1147.5 | 41.6 | 1023.3 | 3.3 | 57.1 | 1.2 | 0.02 |

| Cold temperate humid montane meadow | 152.4 | 41.9 | 993.9 | 56.3 | 1387.7 | 48.3 | 1171.2 | 3.8 | 101.8 | 7.2 | 0.16 |

| Cool temperate subhumid montane grassland | 218.3 | 39.4 | 0.0 | 63.5 | 1568.8 | 45.8 | 1096.3 | 4.1 | 152.3 | 10.2 | 0.21 |

| Alpine meadow | 82,870.3 | 23.1 | 0.0 | 103.2 | 2456.2 | 68.3 | 1566.3 | 21.3 | 465.2 | 5760.5 | 114.15 |

| Cold temperate wet coniferous forest | 29,678.5 | 42.9 | 0.0 | 103.7 | 2498.1 | 87.6 | 2025.9 | 12.5 | 290.0 | 2634.4 | 52.88 |

| Cool temperate wet mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forest | 4.6 | 54.4 | 1211.7 | 56.7 | 1341.0 | 55.6 | 1300.0 | 0.9 | 51.8 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Grassland Type | Increasing Significant Ratio | Decreasing Significant Ratio | Mean Slope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cool temperate subhumid meadow steppe | 0.000 | 0.000 | 9.909 |

| Cold temperate humid montane meadow | 0.089 | 0.000 | 23.998 |

| Cool temperate subhumid montane grassland | 0.048 | 0.000 | 17.942 |

| Alpine meadow | 0.247 | 0.026 | 9.761 |

| Cold temperate wet coniferous forest | 0.119 | 0.006 | 5.585 |

| Cool temperate wet mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forest | 0.000 | 0.000 | 7.938 |

| Grassland Type | Total Carbon Value (USD × 107 tC) | Cumulative Per Area Value (USD/ha) | Average Annual Per Area Value (USD/ha/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cool temperate subhumid meadow steppe | 0.026 | 2046.60 | 102.33 |

| Cold temperate humid montane meadow | 0.178 | 2342.47 | 117.12 |

| Cool temperate subhumid montane grassland | 0.239 | 2192.68 | 109.63 |

| Alpine meadow | 129.796 | 3132.52 | 156.63 |

| Cold temperate wet coniferous forest | 60.127 | 4051.88 | 202.59 |

| Cool temperate wet mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forest | 0.006 | 2600.07 | 130.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, Z.; Su, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, H. Spatial Distribution and Driving Mechanisms of Soil Organic Carbon in the Yellow River Source Region. Land 2026, 15, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010065

Zhou Z, Su J, Ma H, Wang X, Lin H. Spatial Distribution and Driving Mechanisms of Soil Organic Carbon in the Yellow River Source Region. Land. 2026; 15(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Zhenying, Jinxi Su, Haili Ma, Xinyu Wang, and Huilong Lin. 2026. "Spatial Distribution and Driving Mechanisms of Soil Organic Carbon in the Yellow River Source Region" Land 15, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010065

APA StyleZhou, Z., Su, J., Ma, H., Wang, X., & Lin, H. (2026). Spatial Distribution and Driving Mechanisms of Soil Organic Carbon in the Yellow River Source Region. Land, 15(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010065