Temporal Evolution and Extremes of Urban Thermal and Humidity Environments in a Tibetan Plateau City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

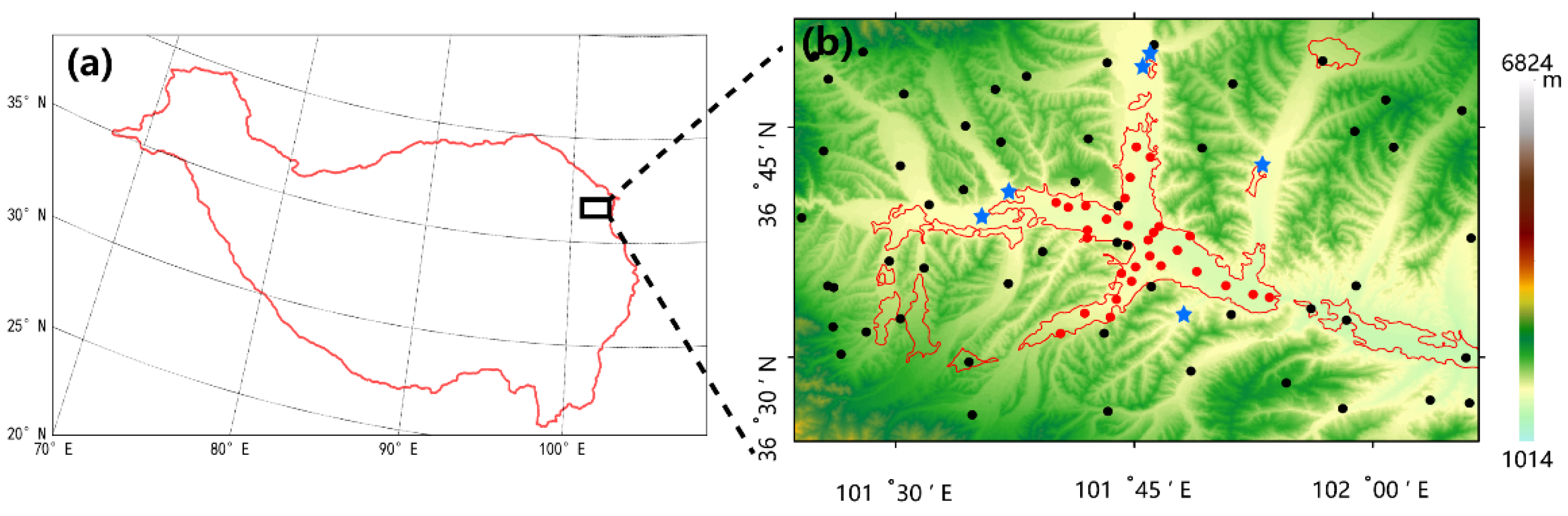

2.2. Urban and Rural Station Classification

2.3. Calculation of UHII and UDII

2.4. Definition of Extreme UHII and UDII Days

2.5. Other Statistical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

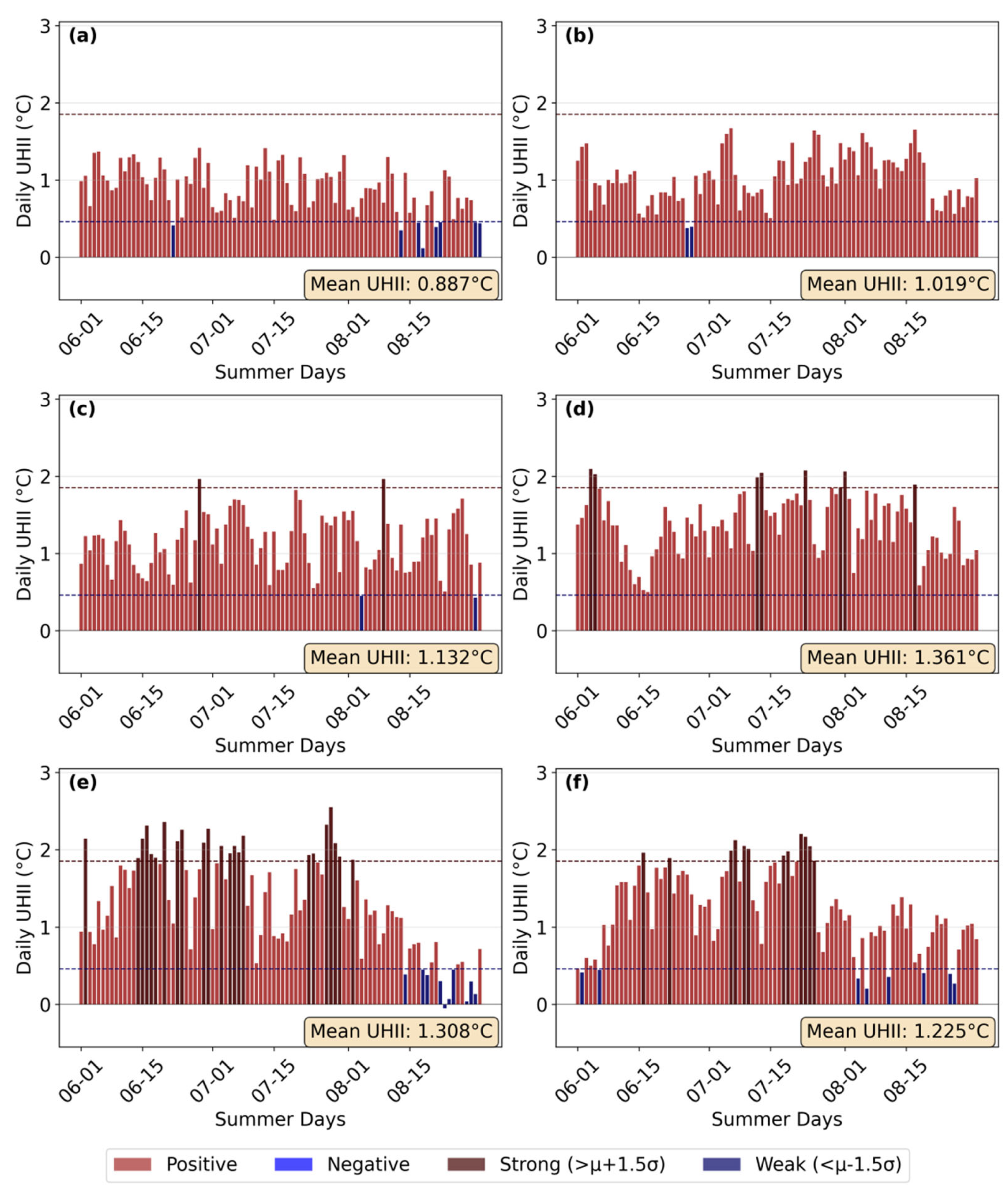

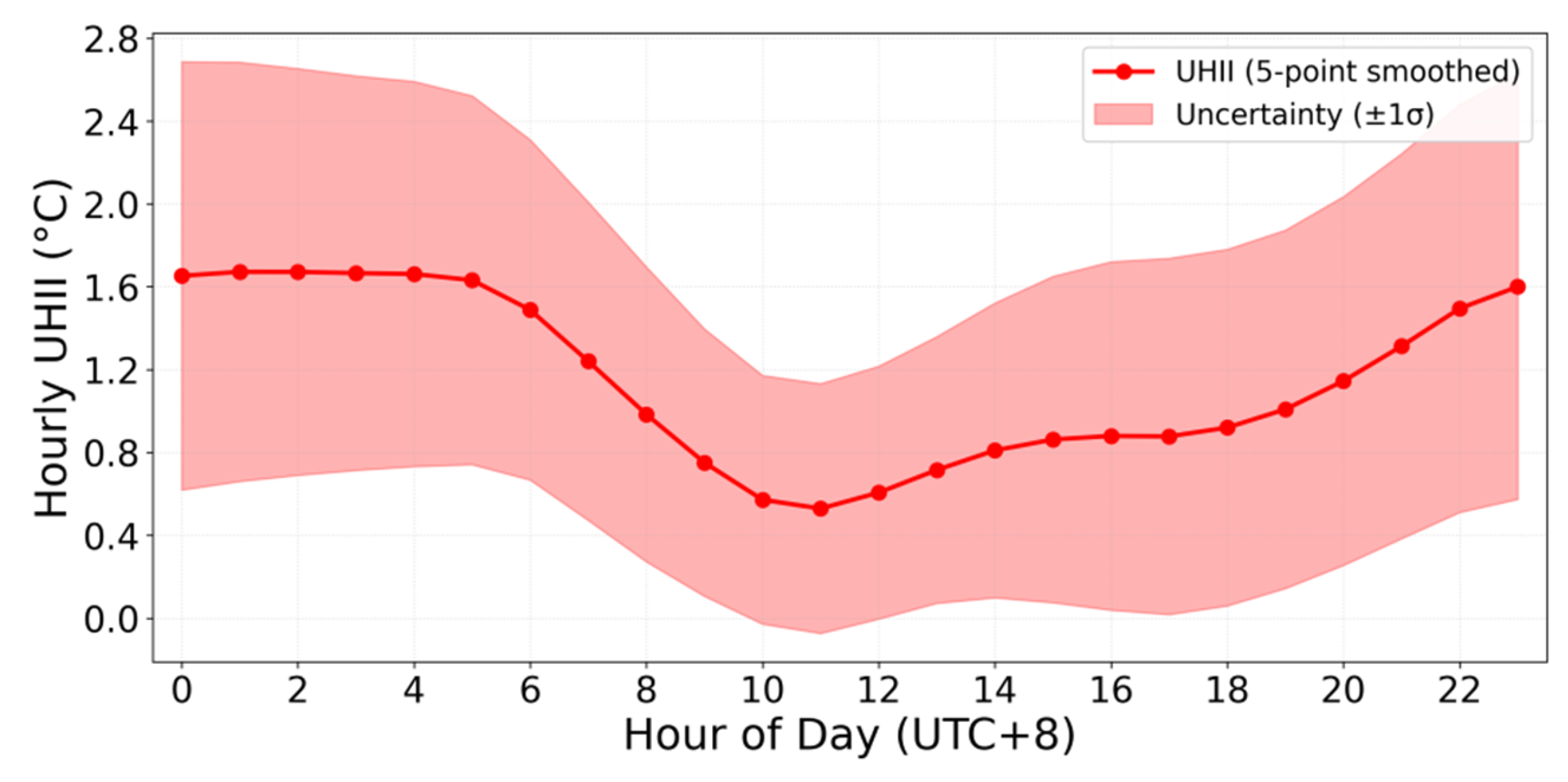

3.1. Summer UHII and Their Extreme

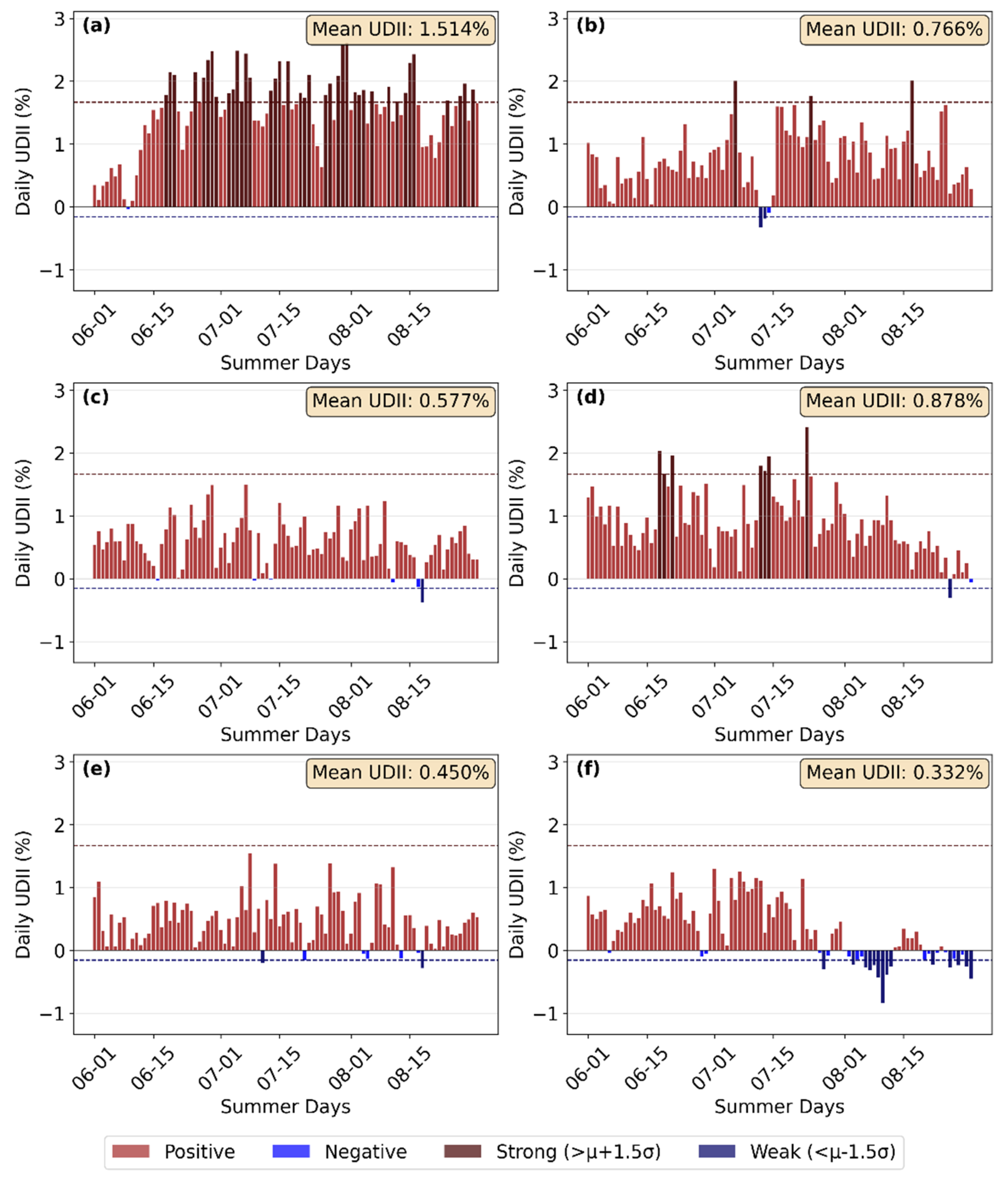

3.2. Summer UDII and Their Extreme

4. Conclusions

- Despite interannual variability, the summer mean UHII has intensified recently. The variability in both daily and hourly UHII increased significantly, reflecting greater instability in the urban thermal environment both on a diurnal and inter-summer scale. This heightened volatility is exemplified by the steady rise in the summer maximum hourly UHII, which climbed from 3.95 °C in 2018 to 6.60 °C in 2023, signaling a growing risk of intense, short-duration heat island events. The frequency of strong UHI days surged markedly. Such days were rare during 2018–2020 (0–2 days per summer), peaked at 23 days in 2022, and remained elevated at 12 days in 2023, representing the most prominent extreme characteristic in recent years. The year 2022 stood out in particular, not only recording the only negative daily UHII value (–0.05 °C) but also exhibiting the highest number of both strong and weak UHI days, along with the largest standard deviation. This underscores a pronounced increase in the volatility of UHII extremes in the latter part of the study period.

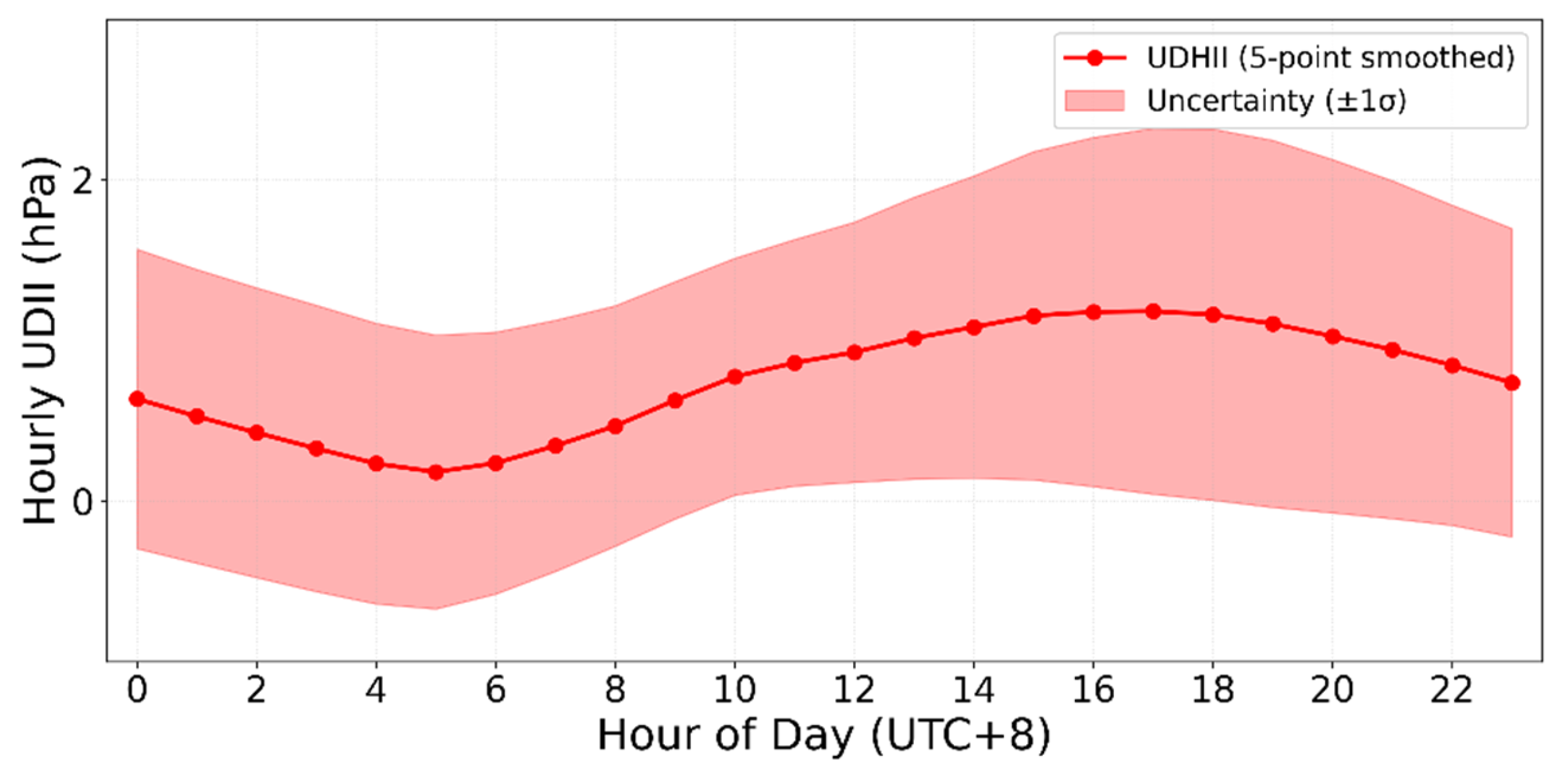

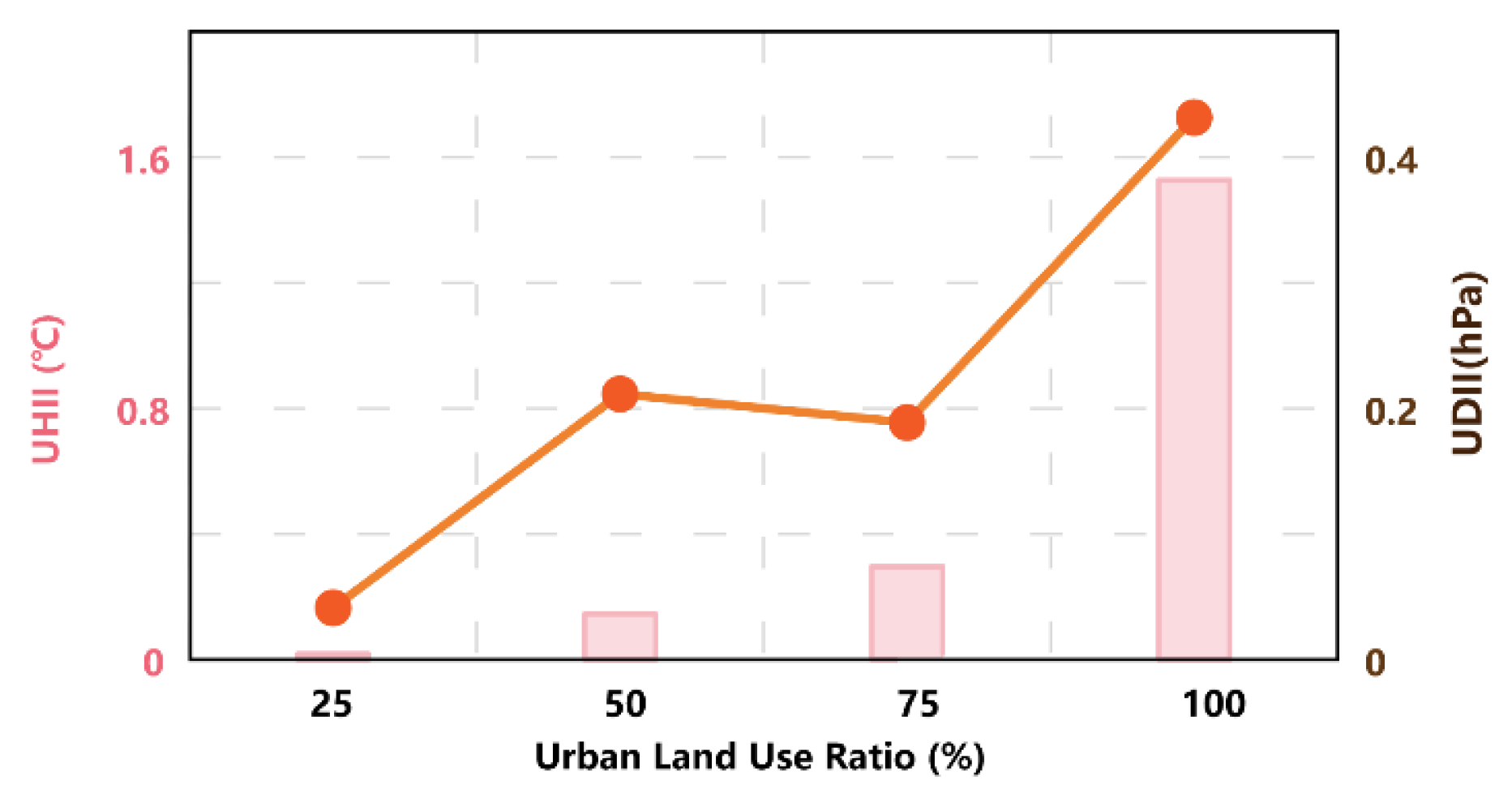

- Based on actual vapor pressure calculations, UDI effect remains a persistent summer feature in Xining, with a six-year mean daily UDII of 0.75 hPa. However, the summer mean UDII shows a fluctuating yet clear weakening, declining from 1.51 hPa in 2018 to 0.33 hPa in 2023. This indicates a recent reduction in the urban–rural humidity contrast over the study period. Corresponding changes are observed in the frequency of extreme dry island days, weak UDI days increased substantially, reaching 14 days in 2023, whereas strong UDI days decreased markedly from 39 days in 2018 to only 0–3 days in most subsequent years. Diurnally, the UDI follows a regular pattern of daytime intensification and nocturnal weakening. Mean daytime UDII is substantially stronger than nighttime UDII, peaking around 17:00–18:00.

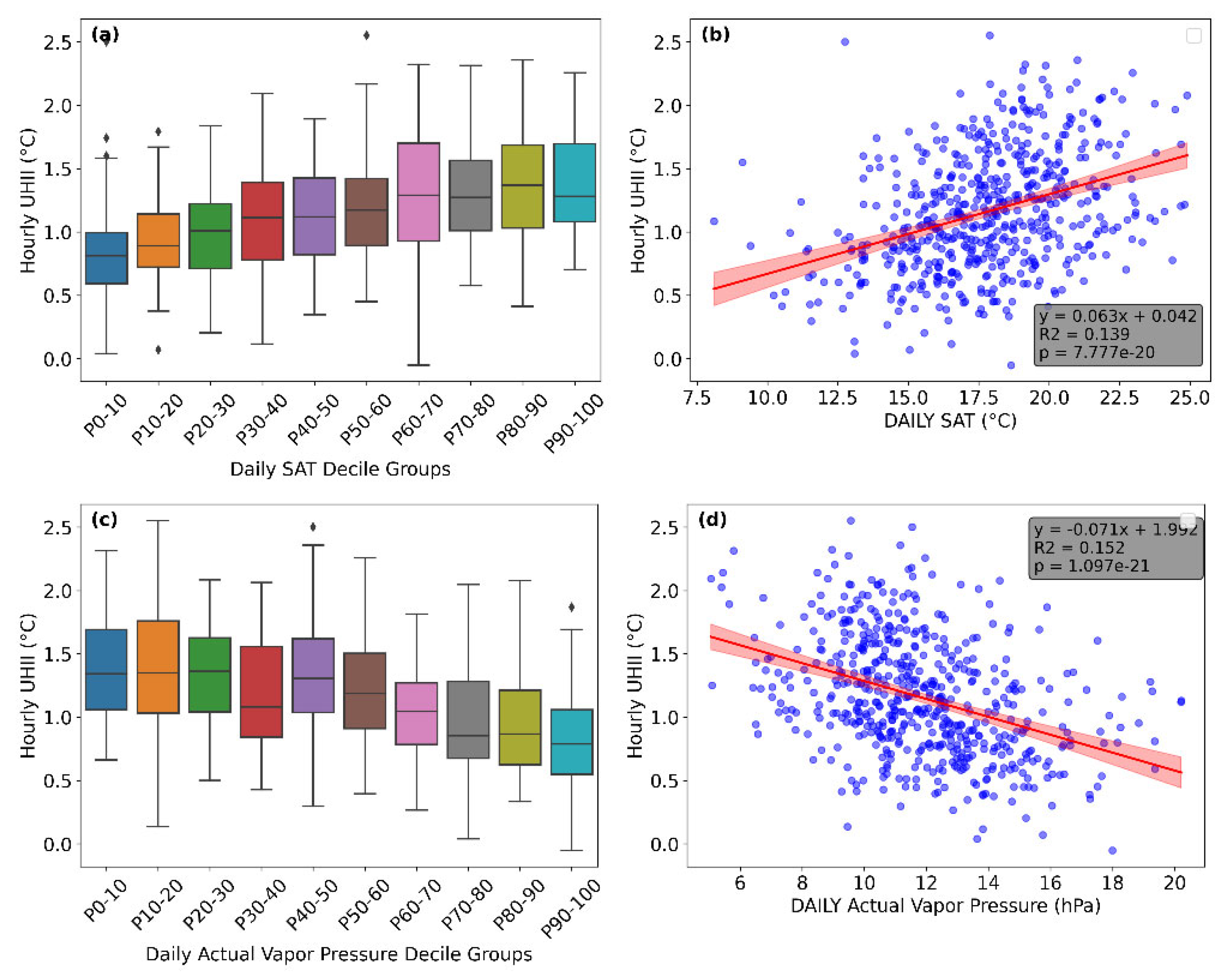

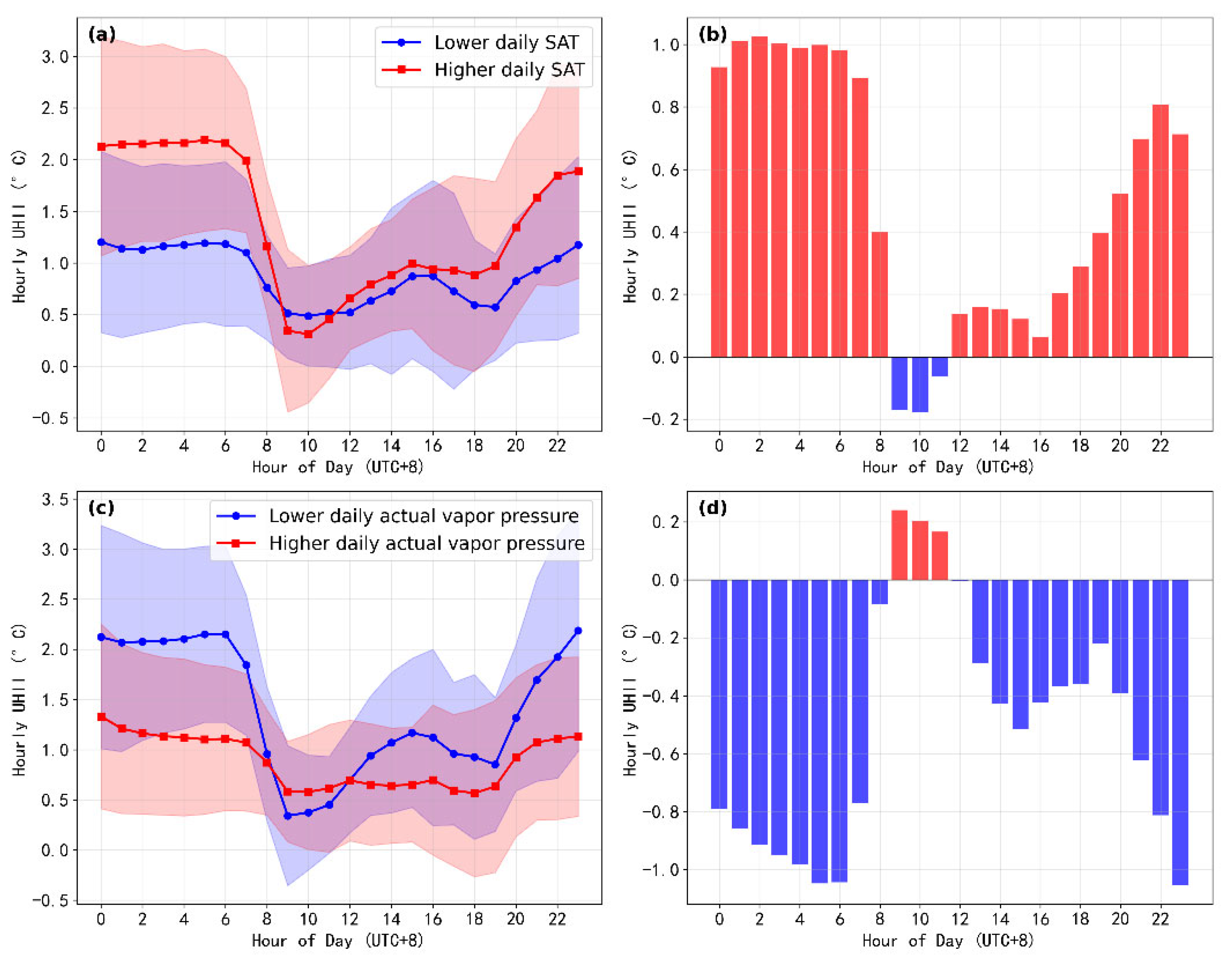

- Summer hourly UHII in Xining is significantly modulated by background meteorological conditions, exhibiting a strong positive correlation with air temperature and a more substantial negative correlation with humidity. Notably, atmospheric humidity demonstrates greater explanatory power for UHII variability than temperature, underscoring the necessity of a multi-factorial perspective in UHI analysis and mitigation. Furthermore, these influences display pronounced diurnal asymmetry, being strongest at night and weak or even reversed during the pre-noon hours.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oke, T.R.; Mills, G.; Christen, A.; Voogt, J.A. Urban Climates; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, T.N.; Boland, F.E. Analysis of urban-rural canopy using a surface heat flux/temperature model. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1978, 17, 998–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 1535. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.F.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhuang, D.F.; Zhang, W.; Liu, M.L. Assessing the effect of land use/land cover change on the change of urban heat island intensity. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2007, 90, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.M.; Dickinson, R.E.; Tian, Y.; Fang, J.; Li, Q.; Kaufmann, R.K.; Tucker, C.J.; Myneni, R.B. Evidence for a significant urbanization effect on climate in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9540–9544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tysa, S.K.; Ren, G.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ren, Y.; Jia, W.; Wen, K. Urbanization Effect in Regional Temperature Series Based on a Remote Sensing Classification Scheme of Stations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 10646–10661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, A.; Guo, J.; Liu, X. Urbanization effects on observed surface air temperature trends in north China. J. Clim. 2008, 21, 1333–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Wu, B.-W.; Shi, C.-E.; Zhang, J.-H.; Li, Y.-B.; Tang, W.-A.; Wen, H.-Y.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Shi, T. Impacts of urbanization and station-relocation on surface air temperature series in Anhui province, China. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2013, 170, 1969–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Chen, S.; Mo, H.; Wang, W.; Yu, P.; Wang, X.; Chuduo, N.; Ba, B. Contribution of urban expansion to surface warming in high-altitude cities of the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Change 2022, 175, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Meng, C.; Xie, Q. Characterizing surface and canopy urban heat islands and impacts of land use and land cover change in a third-pole city. Urban Clim. 2025, 63, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Yu, L.; Wang, Z. Identifying the dominant impact factors and their contributions to heatwave events over mainland China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, X.; Tan, J.; Zhi, X.; Gyi, J.; Lu, Y.; Liu, D. Synergistic interaction between urban heat island and heat waves and its impact factors in Shanghai. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 1789–1802. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Founda, D.; Santamouris, M. Synergies between Urban Heat Island and Heat Waves in Athens (Greece), during an extremely hot summer (2012). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Lee, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, K. Amplified Urban Heat Islands during Heat Wave Periods. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 7797–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zong, L.; Yang, Y.; Bi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M. Diurnal and interannual variations of canopy urban heat island (CUHI) effects over a mountain–valley city with a semi-arid climate. Urban Clim. 2023, 48, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, L.W.; Liu, X.; Li, X.-X.; Norford, L.K. Interaction between heat wave and urban heat island: A case study in a tropical coastal city, Singapore. Atmos. Res. 2021, 247, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Jia, G. Changes in urban heat island intensity during heatwaves in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 074061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, D.; Yuan, X. The Role of Vapor Pressure Deficit in the CLM Simulated Interaction Between Urban Heat Islands and Heat Waves Over CONUS. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL113257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.D.; Chang, C. Shanghai urban influences on humidity and precipitation distribution. GeoJournal 1984, 8, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, T.J. Absolute and relative humidities in towns. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1967, 48, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, B. Climatology of Chicago area urban-rural differences in humidity. J. Clim. Appl. Meteorol. 1987, 26, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.O. Urban—Rural humidity differences in London. Int. J. Climatol. 1991, 11, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, Y.; Hamotani, K.; Um, H.H. Recent changes in trends of humidity of Japanese cities. J. Jpn. Soc. Hydrol. Water Resour. 1994, 7, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Ren, G.Y.; Hou, W. Temporal–spatial patterns of relative humidity and the urban dryness island effect in Beijing City. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2017, 56, 2221–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hao, L.; Sun, G.; Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, D. Urbanization Aggravates Effects of Global Warming on Local Atmospheric Drying. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL095709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, J.; Kucharik, C.J. Seasonality of the Urban Heat Island Effect in Madison, Wisconsin. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2014, 53, 2371–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnds, D.; Böhner, J.; Bechtel, B. Spatio-temporal variance and meteorological drivers of the urban heat island in a European city. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 128, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, L.; Mu, K.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J. Urban heat island effects of various urban morphologies under regional climate conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, P.; Krueger, O.; Schlünzen, K.H. A statistical model for the urban heat island and its application to a climate change scenario. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 32, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Bolch, T.; Chen, D.; Gao, J.; Immerzeel, W.; Piao, S.; Su, F.; Thompson, L.; Wada, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. The imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Jiao, J.J. Review on climate change on the Tibetan Plateau during the last half century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 3979–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Leung, L.R.; Zhang, Y.; Cuo, L. Changes in Moisture Flux over the Tibetan Plateau during 1979–2011: Insights from a High-Resolution Simulation. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 4185–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterling, D.R.; Wehner, M.F. Is the climate warming or cooling? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L08706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santer, B.D.; Bonfils, C.; Painter, J.F.; Zelinka, M.D.; Mears, C.; Solomon, S.; Schmidt, G.A.; Fyfe, J.C.; Cole, J.N.S.; Nazarenko, L.; et al. Volcanic contribution to decadal changes in tropospheric temperature. Nat. Geosci. 2014, 7, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Min, J.; Kang, S. Rapid warming in the Tibetan Plateau from observations and CMIP5 models in recent decades. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 2660–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, S.; Xu, W.; Wang, X.L.; Jones, P.; Parker, D.; Zhou, L.; Feng, Y.; Gao, Y. China experiencing the recent warming hiatus. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; He, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z. Understanding Urban Expansion on the Tibetan Plateau over the Past Half Century Based on Remote Sensing: The Case of Xining City, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Z.; Liu, F.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, W. Study on the Urban Expansion of Typical Tibetan Plateau Valley Cities and Changes in Their Ecological Service Value: A Case Study of Xining, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cao, C.; Dubovyk, O.; Tian, R.; Chen, W.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Menz, G. Using fuzzy analytic hierarchy process for spatio-temporal analysis of eco-environmental vulnerability change during 1990–2010 in Sanjiangyuan region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 73, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhang, C.N.; Lin, Z.B.; Mao, X.F.; Liu, S.H.; Liu, Z.F. A Multi-scale evaluation study on the shading effects of street trees at noon in summer in Xining City. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 4728–4742. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S.; Tysa, S.K. Divergent Urban Canopy Heat Island Responses to Heatwave Type over the Tibetan Plateau: A Case Study of Xining. Land 2025, 14, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, K.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. Land-atmosphere coupling amplified the record-breaking heatwave at altitudes above 5000 meters on the Tibetan Plateau in July 2022. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2024, 45, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Baik, J.-J.; Jin, H.-G.; Tabassum, A. Changes in urban heat island intensity with background temperature and humidity and their associations with near-surface thermodynamic processes. Urban Clim. 2024, 58, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindell, D.; Kuylenstierna, J.C.I.; Vignati, E.; van Dingenen, R.; Amann, M.; Klimont, Z.; Anenberg, S.C.; Muller, N.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; Raes, F.; et al. Simultaneously Mitigating Near-Term Climate Change and Improving Human Health and Food Security. Science 2012, 335, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, G.R. Special issue: Universal Thermal Comfort Index (UTCI). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröde, P.; Fiala, D.; Błażejczyk, K.; Holmér, I.; Jendritzky, G.; Kampmann, B.; Tinz, B.; Havenith, G. Deriving the operational procedure for the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potchter, O.; Cohen, P.; Lin, T.-P.; Matzarakis, A. Outdoor human thermal perception in various climates: A comprehensive review of approaches, methods and quantification. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazejczyk, K.; Epstein, Y.; Jendritzky, G.; Staiger, H.; Tinz, B. Comparison of UTCI to selected thermal indices. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendritzky, G.; de Dear, R.; Havenith, G. UTCI—Why Another Therm. Index? Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Schubert, S.; Fenner, D.; Salim, M.H.; Schneider, C. Estimation of mean radiant temperature in cities using an urban parameterization and building energy model within a mesoscale atmospheric model. Meteorol. Z 2022, 31, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Schubert, S.; Salim, M.H.; Schneider, C. Impact of Air Conditioning Systems on the Outdoor Thermal Environment during Summer in Berlin, Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station Type | Station ID | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | Altitude (m) | Station ID | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban station | 1 | 36.6356 | 101.7703 | 2229 | 16 | 36.5258 | 101.6728 | 2533 |

| 2 | 36.5778 | 101.8461 | 2213 | 17 | 36.5825 | 101.7472 | 2321 | |

| 3 | 36.5628 | 101.7314 | 2368 | 18 | 36.5911 | 101.7367 | 2345 | |

| 4 | 36.7172 | 101.7669 | 2283 | 19 | 36.61 | 101.7664 | 2359 | |

| 5 | 36.6317 | 101.8083 | 2269 | 20 | 36.565 | 101.8919 | 2176 | |

| 6 | 36.5994 | 101.7781 | 2405 | 21 | 36.5683 | 101.8747 | 2187 | |

| 7 | 36.6953 | 101.7458 | 2312 | 22 | 36.6728 | 101.7403 | 2330 | |

| 8 | 36.6628 | 101.6808 | 2288 | 23 | 36.6681 | 101.6681 | 2315 | |

| 9 | 36.6381 | 101.7011 | 2297 | 24 | 36.5436 | 101.7250 | 2410 | |

| 10 | 36.6419 | 101.7761 | 2241 | 25 | 36.6644 | 101.6992 | 2282 | |

| 11 | 36.5478 | 101.6981 | 2413 | 26 | 36.5981 | 101.7514 | 2317 | |

| 12 | 36.6272 | 101.7647 | 2260 | 27 | 36.6297 | 101.7008 | 2314 | |

| 13 | 36.7283 | 101.7522 | 2312 | 28 | 36.6161 | 101.7953 | 2238 | |

| 14 | 36.6431 | 101.7436 | 2245 | 29 | 36.5931 | 101.8156 | 2232 | |

| 15 | 36.65 | 101.7211 | 2259 | |||||

| Rural station | 1 | 36.8156 | 101.7589 | 2315 | 4 | 36.5456 | 101.5903 | 2349 |

| 2 | 36.6519 | 101.5903 | 2336 | 5 | 36.6797 | 101.6189 | 2353 | |

| 3 | 36.8292 | 101.7667 | 2346 | 6 | 36.7089 | 101.8844 | 2354 |

| Year | Peak Time (UTC + 8) | Trough Time (UTC + 8) | Standard Deviation (°C) | Maximum Hourly UHII (°C) | Minimum Hourly UHII (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 5:00 | 10:00 | 0.687 | 3.950 | −2.075 |

| 2019 | 1:00 | 9:00 | 0.720 | 4.011 | −2.000 |

| 2020 | 0:00 | 10:00 | 0.963 | 5.973 | −1.255 |

| 2021 | 5:00 | 9:00 | 1.165 | 5.421 | −2.673 |

| 2022 | 0:00 | 9:00 | 1.082 | 5.882 | −3.105 |

| 2023 | 23:00 | 10:00 | 0.988 | 6.603 | −1.971 |

| Year | Peak Time (UTC + 8) | Trough Time (UTC + 8) | Standard Deviation (hPa) | Maximum Hourly UDII (hPa) | Minimum Hourly UDII (hPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 7:00 | 18:00 | 0.96 | 2.05 | −6.19 |

| 2019 | 6:00 | 17:00 | 0.89 | 3.18 | −5.34 |

| 2020 | 6:00 | 16:00 | 0.87 | 3.20 | −4.76 |

| 2021 | 6:00 | 17:00 | 1.04 | 3.11 | −8.63 |

| 2022 | 6:00 | 17:00 | 0.80 | 2.36 | −4.66 |

| 2023 | 6:00 | 15:00 | 0.98 | 2.47 | −4.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Tysa, S.K.; Chen, G.; Li, Q. Temporal Evolution and Extremes of Urban Thermal and Humidity Environments in a Tibetan Plateau City. Land 2026, 15, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010064

Wang J, Tysa SK, Chen G, Li Q. Temporal Evolution and Extremes of Urban Thermal and Humidity Environments in a Tibetan Plateau City. Land. 2026; 15(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jinzhao, Suonam Kealdrup Tysa, Guoxin Chen, and Qiong Li. 2026. "Temporal Evolution and Extremes of Urban Thermal and Humidity Environments in a Tibetan Plateau City" Land 15, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010064

APA StyleWang, J., Tysa, S. K., Chen, G., & Li, Q. (2026). Temporal Evolution and Extremes of Urban Thermal and Humidity Environments in a Tibetan Plateau City. Land, 15(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010064