Spatially Explicit Modeling of Urban Land Consolidation Potential: A New Bidirectional CA Framework for Reduction Planning Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Land Cover Classification

2.2.1. Data Preprocessing

2.2.2. Classification

2.2.3. Accuracy Assessment

2.2.4. Further Processing

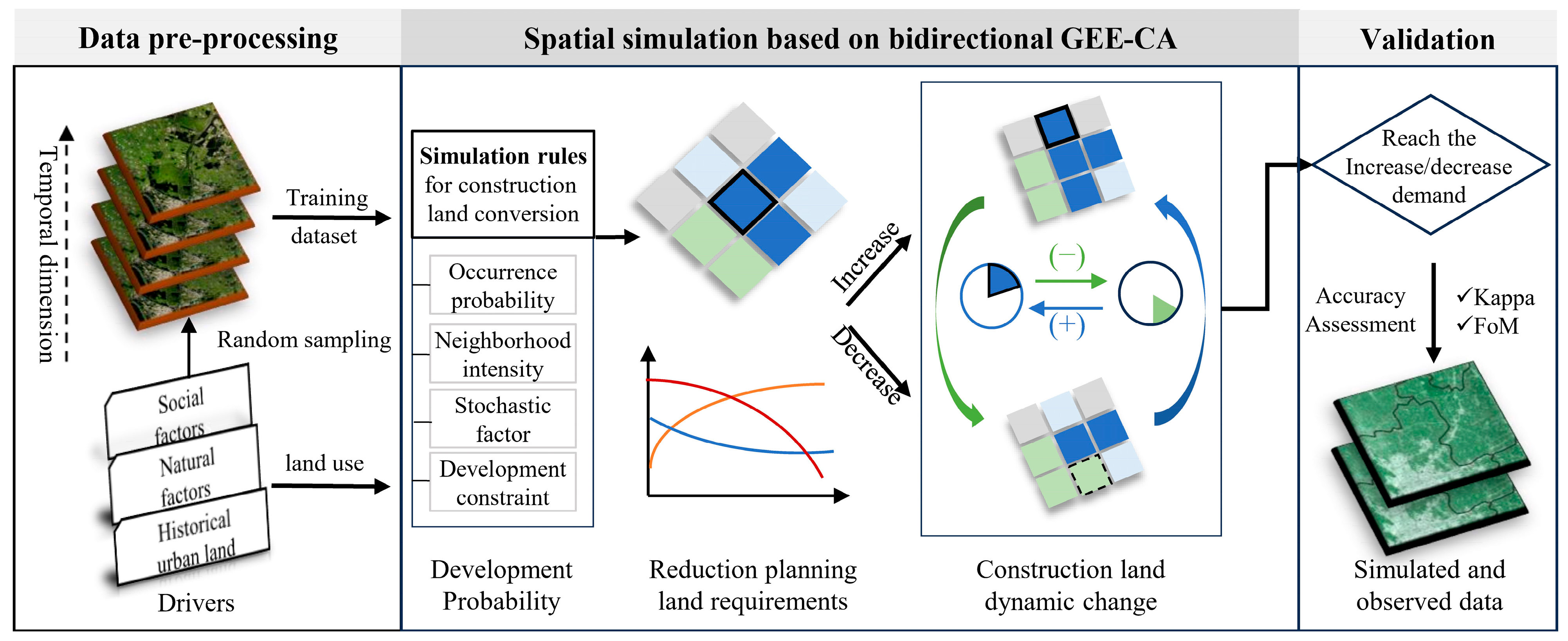

2.3. Bidirectional GEE-CA Framework

2.3.1. Original GEE-CA

2.3.2. Bidirectional GEE-CA

2.3.3. Simulation Workflow

2.3.4. Model Accuracy Validation and Sensitivity Analysis

2.3.5. Future Simulation

3. Results

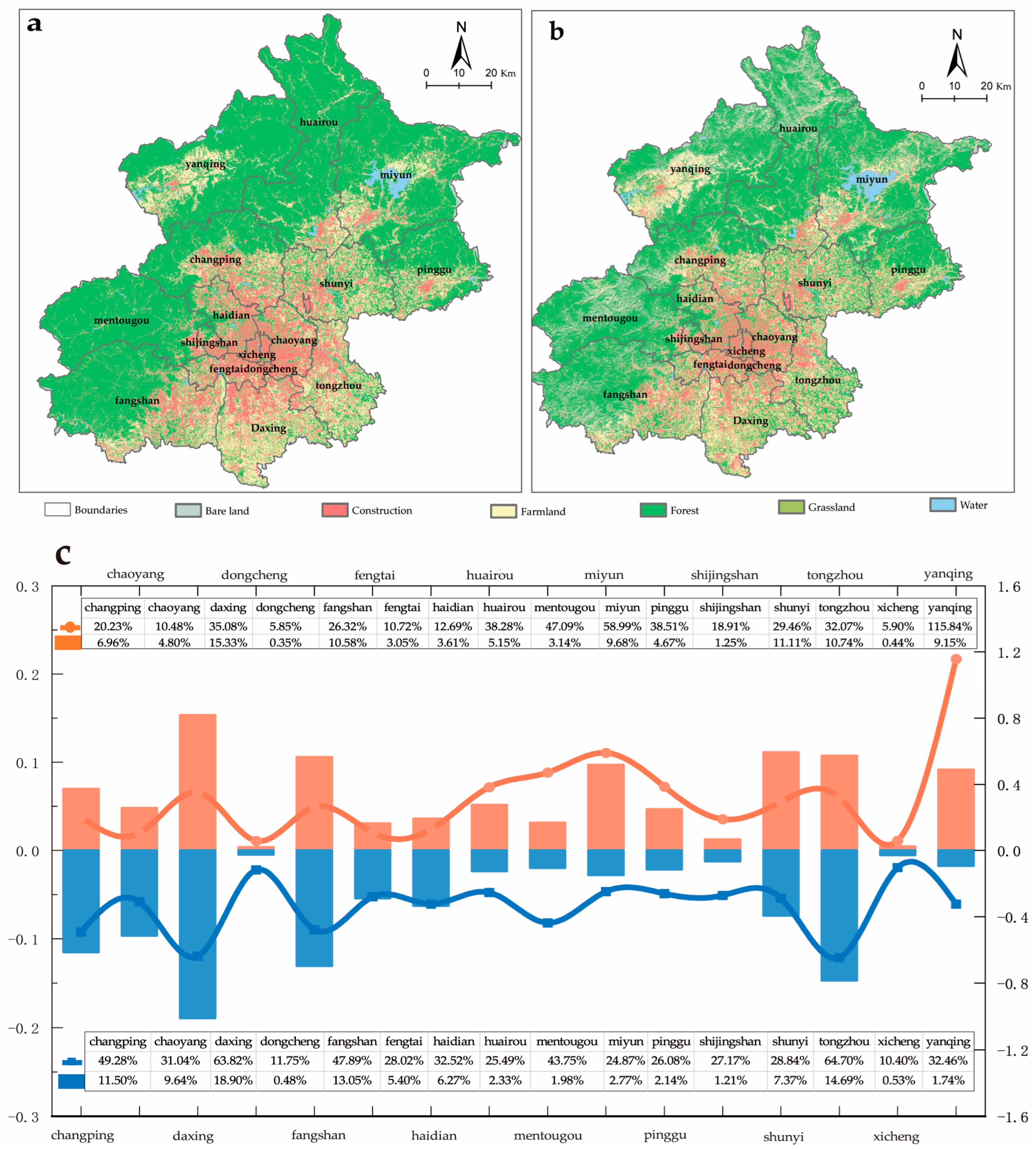

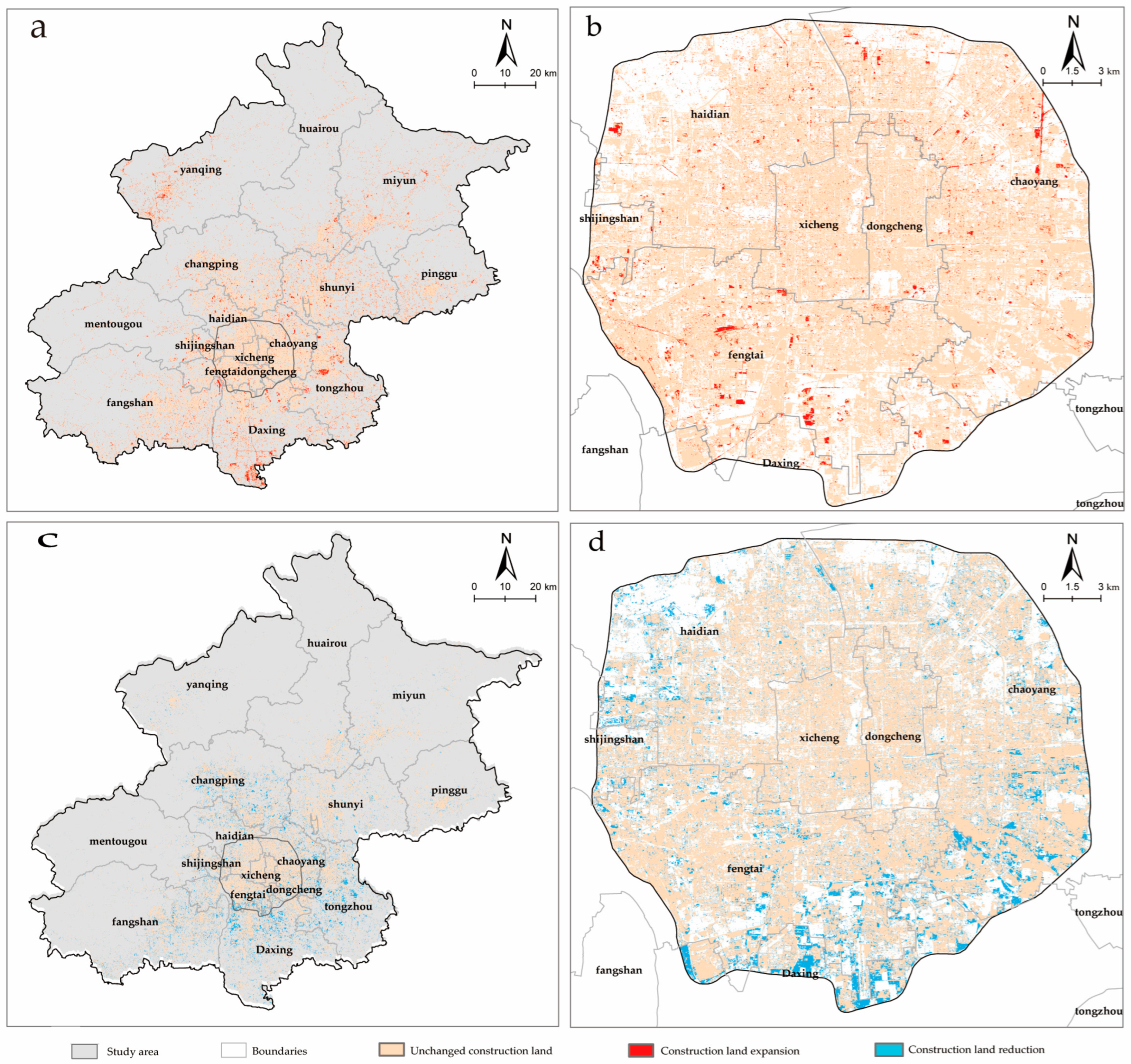

3.1. Urban Renewal in Beijing During 2016–2020

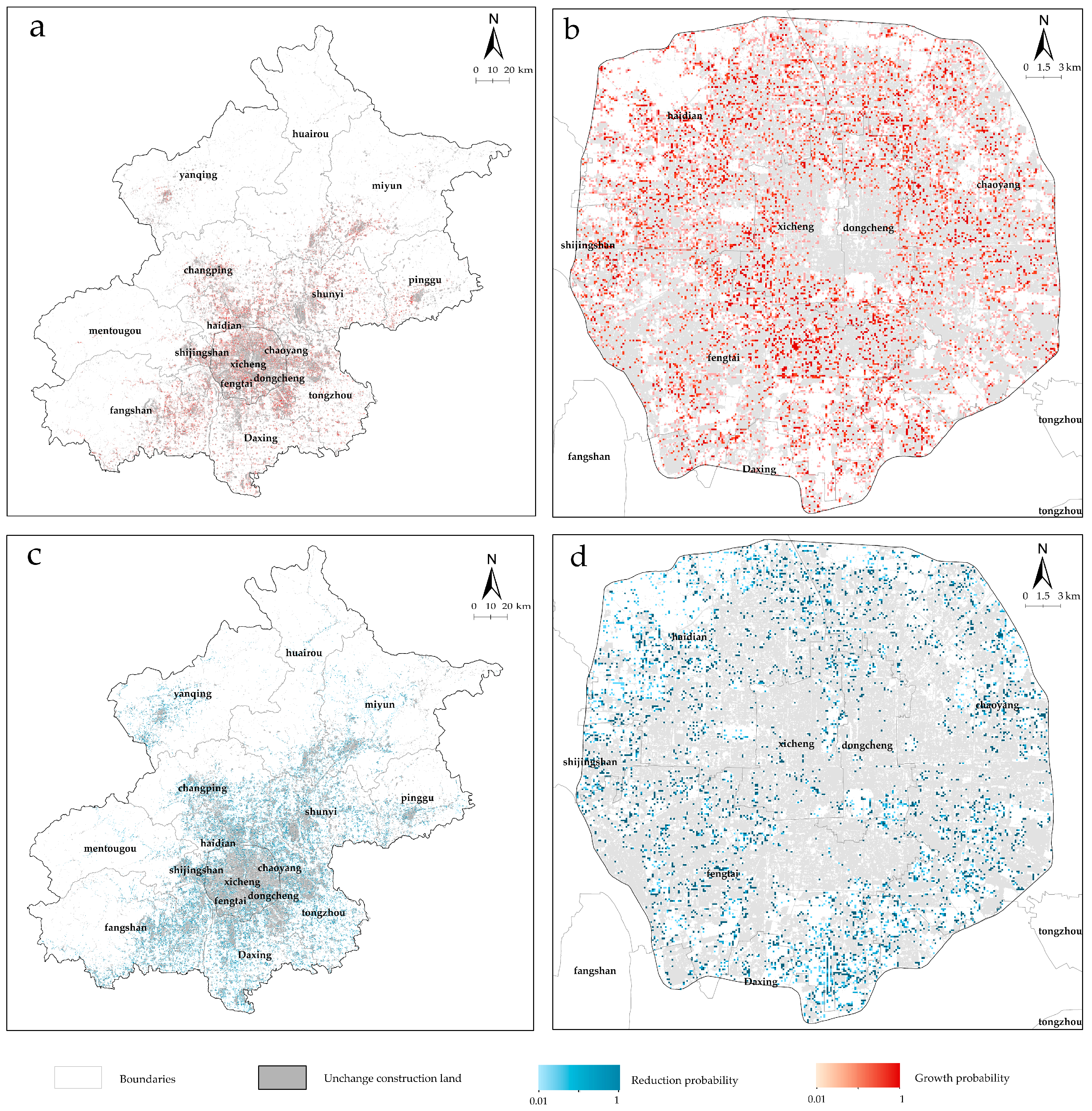

3.1.1. Construction Land Expansion

3.1.2. Construction Land Reduction

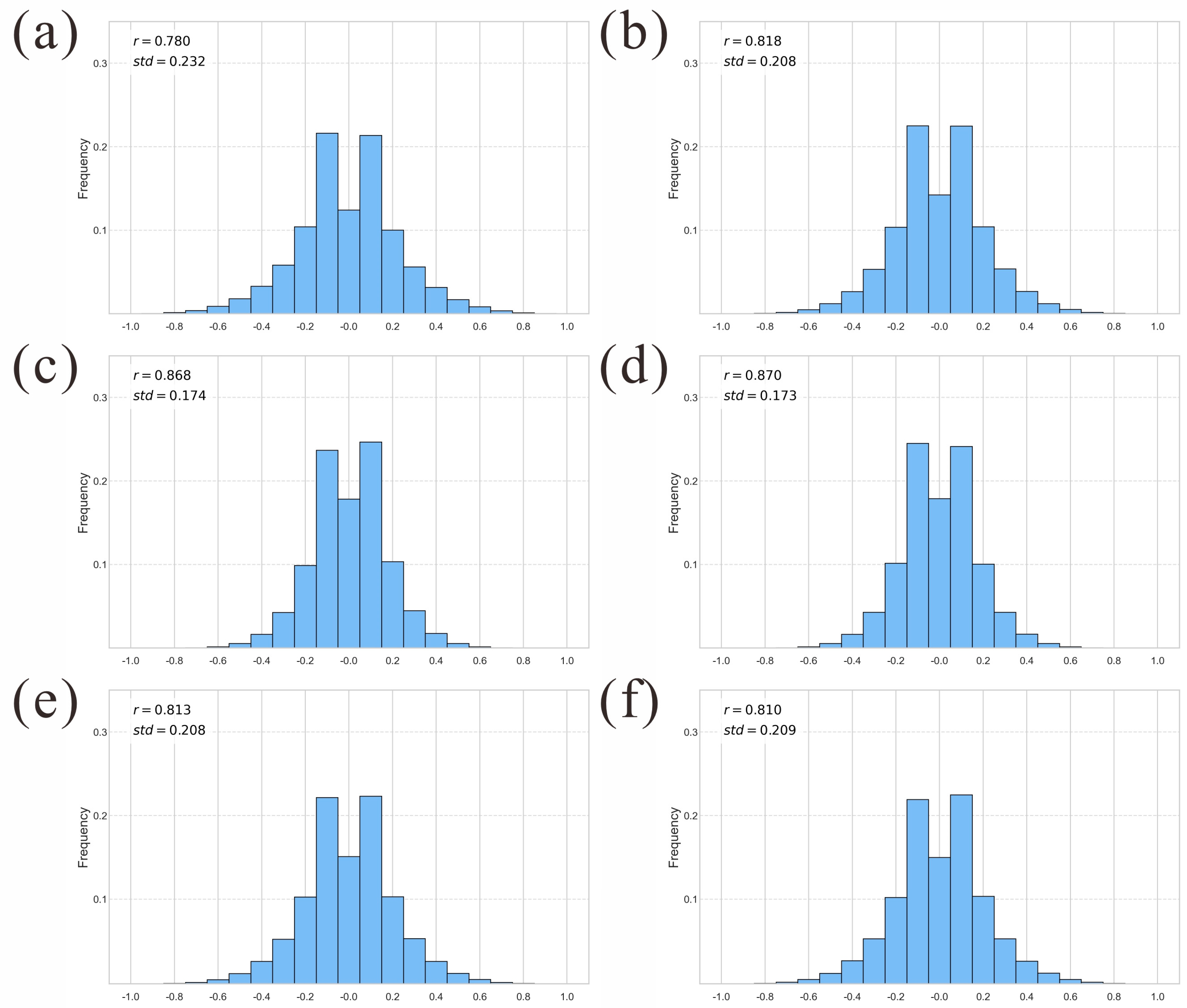

3.2. Results of Validation and Sensitivity Analysis

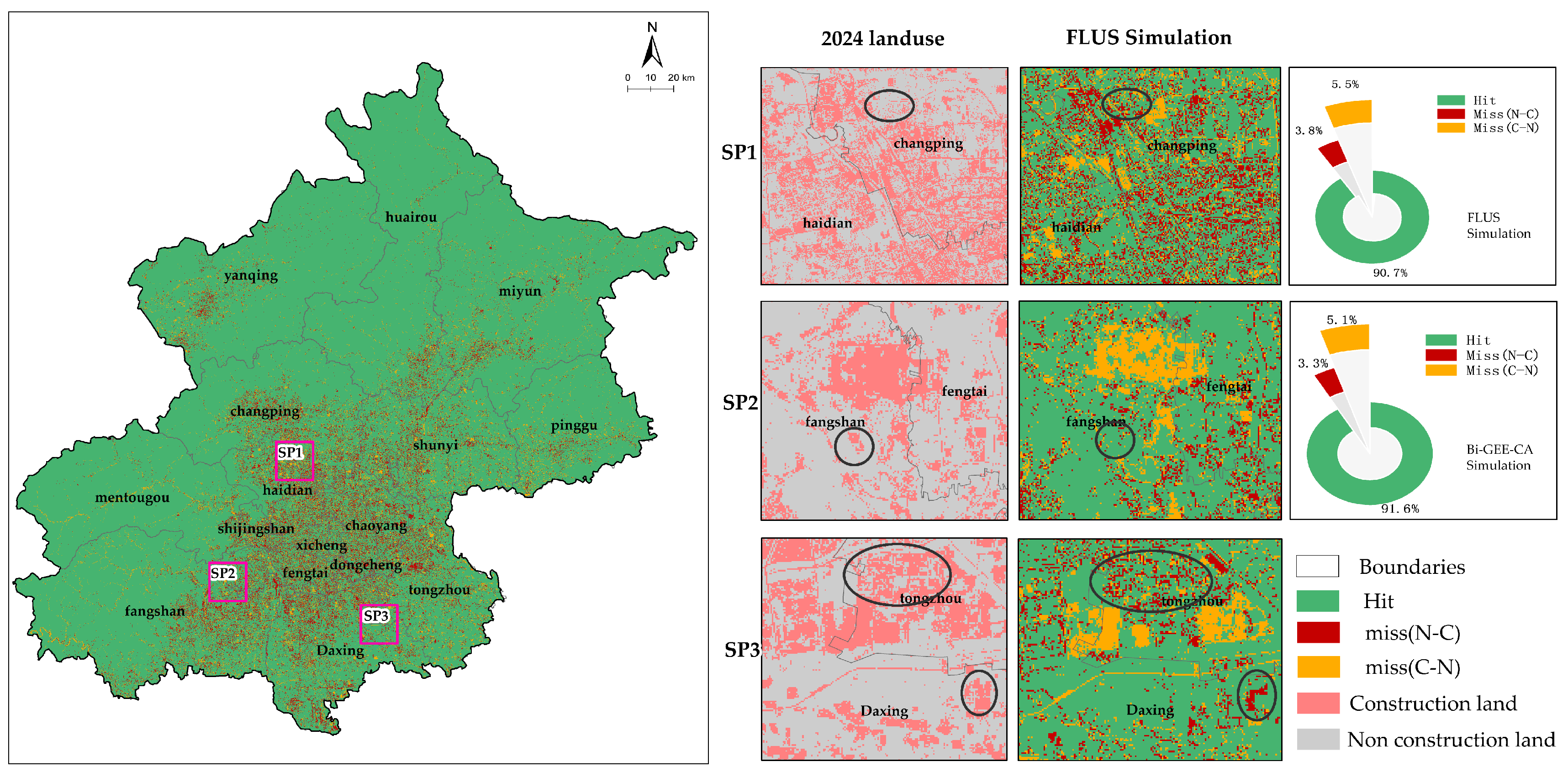

3.2.1. Modeling Validation

3.2.2. Sensitivity Analysis

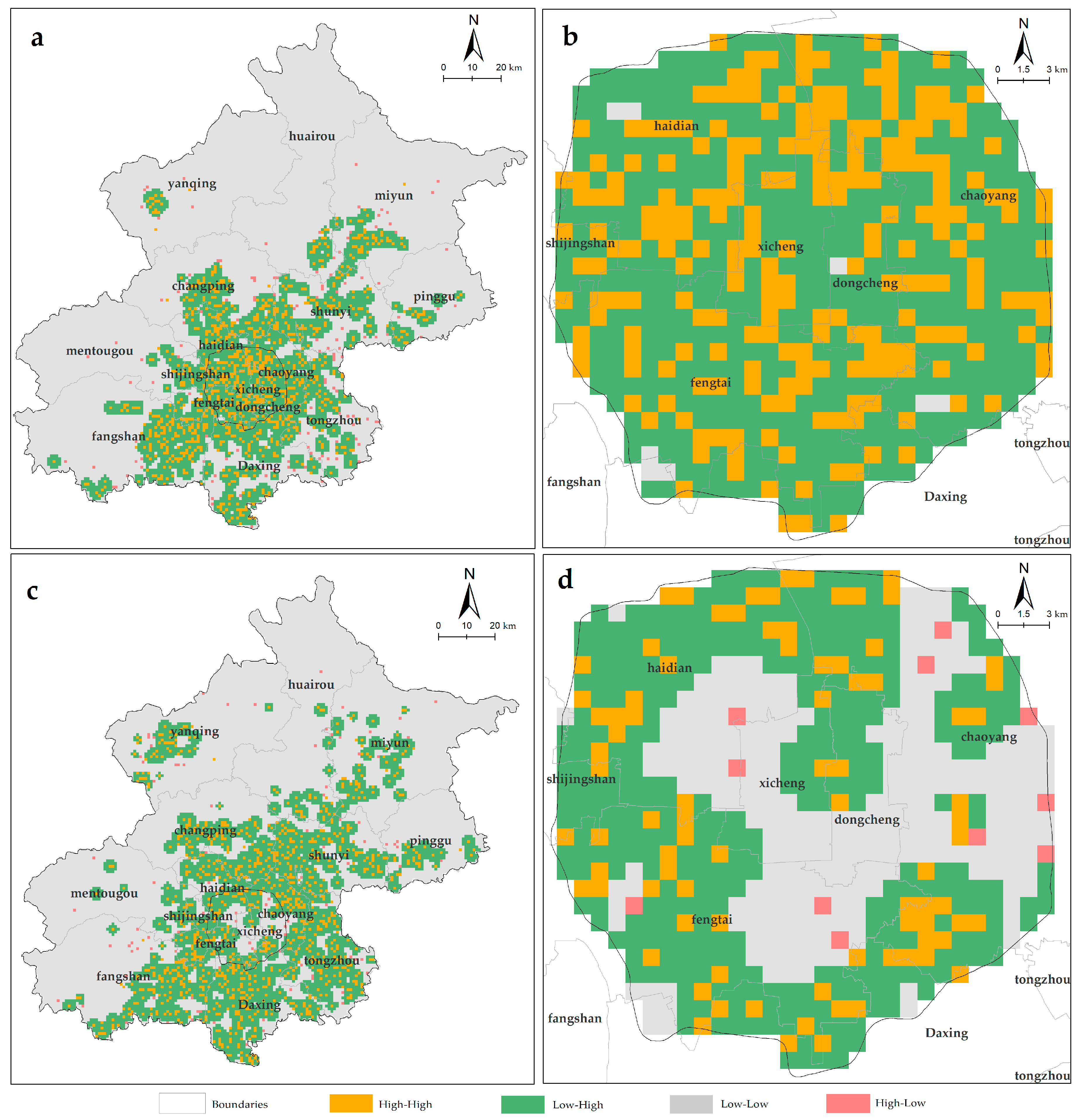

3.3. Spatial Characteristics and Distribution of Construction Land Consolidation Potential

3.3.1. Future Simulation in 2035

3.3.2. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis of Potential Areas

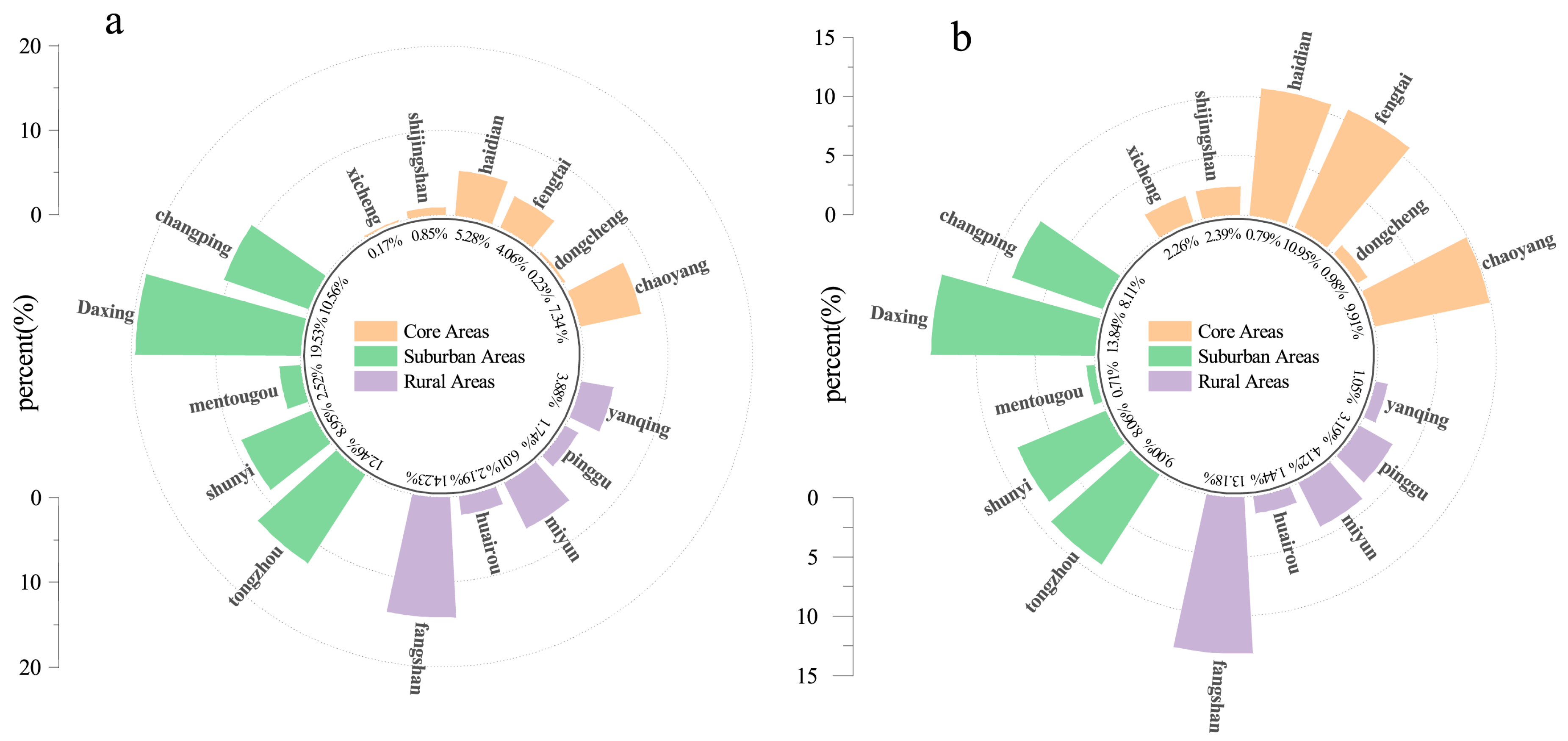

3.3.3. Distribution of Construction Land Consolidation Potential

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Models

4.1.1. Model Comparability

| Authors | Model | Level | FoM | Kappa Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meng et al. [46] | GEE-CA | City | 0.14–0.31 | 0.65–0.95 |

| Liu et al. [56] | FLUS | Regional | 0.12 | 0.79 |

| Saxena and Jat [58] | SLEUTH | City | 0.11–0.3 | 0.4–0.55 |

| Geng et al. [61] | ST-CA | National | 0.18 | 0.99 |

| Wang et al. [63] | Logistic-CA | City | 0.20–0.21 | 0.45–0.47 |

| Chen et al. [65] | FLUS | Regional | 0.12–0.36 | - |

| Zhang et al. [66] | PLUS | City | 0.146 | 0.772 |

| Li et al. [67] | FLUS | Regional | 0.10–0.29 | - |

| This study | Bidirectional GEE-CA | City | 0.19 | 0.68 |

4.1.2. Model Reliability

4.1.3. Inheritance and Development of Models

| Authors | Driving Factors of Construction Land Changes | Transition Restrictions | CA Transition Rules | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation Variables | Proximity Variables | Nighttime Light | Water | Road | Policy | Construction Land Expansion | Construction Land Reduction | |

| Meng et al. [46] | √ | √ | × | √ | × | × | √ | × |

| Liu et al. [56] | √ | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × |

| Chen et al. [65] | √ | √ | √ | × | × | × | √ | × |

| Zhang et al. [66] | √ | √ | × | × | × | √ | √ | × |

| Li et al. [67] | √ | × | × | × | × | √ | √ | × |

| This study | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

4.2. Types of Construction Land Consolidation

4.3. The Applicability of the Model

4.4. Limitations and Further Improvement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Asrar, G.R.; Smith, S.J.; Imhoff, M. A global record of annual urban dynamics (1992–2013) from nighttime lights. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 219, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, R. Function-analysis and valuation as a tool to assess land use conflicts in planning for sustainable, multi-functional landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, P.; Yue, W.; Song, Y. Impacts of land finance on urban sprawl in China: The case of Chongqing. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Zambon, I.; Chelli, F.M.; Serra, P. Do spatial patterns of urbanization and land consumption reflect different socioeconomic contexts in Europe? Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, B.; Tousi, S.N. An explanation of urban sprawl phenomenon in Shiraz Metropolitan Area (SMA). Cities 2018, 73, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Y. Strategic adjustment of land use policy under the economic transformation. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, W.; Alvanides, S.; Garrod, G. Determinants of Urban Sprawl in European Cities. SSRN Electron. J. 2015, 52, 1594–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xu, G.; Tian, Z. Built-up land efficiency in urban China: Insights from the General Land Use Plan (2006–2020). Habitat Int. 2016, 51, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Guneralp, B.; Hutyra, L.R. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16083–16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Deng, X.; Seto, K.C. The impact of urban expansion on agricultural land use intensity in China. Land Use Policy 2013, 35, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ming, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yue, W.; Han, G. Influences of landform and urban form factors on urban heat island: Comparative case study between Chengdu and Chongqing. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, D. Spatiotemporal patterns of summer urban heat island in Beijing, China using an improved land surface temperature. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, A.N.M.; Corstanje, R.; Harris, J.A.; Brewer, T. Impact of rapid urban expansion on green space structure. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 81, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, O.; Blija, D.K.; Ayambire, R.A.; Takyi, S.A.; Mensah, H.; Braimah, I. Global urban sprawl containment strategies and their implications for rapidly urbanising cities in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, C.; van den Bosch, C.K. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Asadi, N. Causes, Results and Methods of Controlling Urban Sprawl. Procedia Eng. 2011, 21, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Tian, H.; Yao, Y. Delineating multi-scenario urban growth boundaries with a CA-based FLUS model and morphological method. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyebi, A.; Perry, P.C.; Tayyebi, A.H. Predicting the expansion of an urban boundary using spatial logistic regression and hybrid raster–vector routines with remote sensing and GIS. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 28, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Knaap, G.J. Measuring Urban Form: Is Portland Winning the War on Sprawl? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2004, 70, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennaio, M.P.; Hersperger, A.M.; Bürgi, M. Containing urban sprawl—Evaluating effectiveness of urban growth boundaries set by the Swiss Land Use Plan. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourtaherian, P.; Jaeger, J.A.G. How effective are greenbelts at mitigating urban sprawl? A comparative study of 60 European cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 227, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gong, Y.; López-Carr, D.; Huang, C. A critical role of the capital green belt in constraining urban sprawl and its fragmentation measurement. Land Use Policy 2024, 141, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Nath, N.; Murayama, A.; Manabe, R. Transit-oriented development with urban sprawl? Four phases of urban growth and policy intervention in Tokyo. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulic, O.; Krklješ, M. Brownfield Redevelopment as a Strategy for Preventing Urban Sprawl. In Proceedings of the Građevinarstvo-Nauka i Praksa, Žabljak, Montenegro, February 2014; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281651820_Brownfield_Redevelopment_as_a_Strategy_for_Preventing_Urban_Sprawl (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Greenberg, M.; Lowrie, K.; Mayer, H.; Miller, K.T.; Solitare, L. Brownfield redevelopment as a smart growth option in the United States. Environmentalist 2001, 21, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, A. Suburban Sprawl or Urban Centres: Tensions and Contradictions of Smart Growth Approaches in Denver, Colorado. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2178–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, T.; Bahadure, S. Investigating application of compact urban form in central Indian cities. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Mu, B.; Ahmad, N. Fostering land use sustainability through construction land reduction in China: An analysis of key success factors using fuzzy-AHP and DEMATEL. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 18755–18777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Pijanowski, B.C. The effects of China’s cultivated land balance program on potential land productivity at a national scale. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 46, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhong, T.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.; Xu, G.; Niu, L.; Li, H. Can annual land use plan control and regulate construction land growth in China? Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Jin, X.; Wang, J.; Yin, Y.; Liu, C.; Sun, R.; Zhou, Y. Identifying inefficient urban land redevelopment potential for evidence-based decision making in China. Habitat Int. 2022, 128, 102661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Cheng, G. Cultivated land loss and construction land expansion in China: Evidence from national land surveys in 1996, 2009 and 2019. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, Z. Transformation of Urban Planning: Thoughts on Incremental Planning, Stock-Based Planning, and Reduction Planning. China City Plan. Rev. 2016, 25, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, X.; Mu, B.; Li, Q. Integrated decision support framework for construction land reduction projects prioritization in China: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Gu, X. Reduction of industrial land beyond Urban Development Boundary in Shanghai: Differences in policy responses and impact on towns and villages. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, B.; Zeng, H. Simulating urban land growth by incorporating historical information into a cellular automata model. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P. Sustainable urban expansion and transportation in a growing megacity: Consequences of urban sprawl for mobility on the urban fringe of Beijing. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 236–243. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Hu, H. Geographical patterns of traffic congestion in growing megacities: Big data analytics from Beijing. Cities 2019, 92, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Ives, C.D.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y. Modes and practices of rural vitalisation promoted by land consolidation in a rapidly urbanising China: A perspective of multifunctionality. Habitat Int. 2022, 121, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Land consolidation boosting poverty alleviation in China: Theory and practice. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y. Land consolidation for rural sustainability in China: Practical reflections and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kong, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, L. Identifying the relationship between urban land expansion and human activities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 94, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in China: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Rural vitalization in China: A perspective of land consolidation. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Tang, Y.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zheng, Y. The impact of land consolidation on rural vitalization at village level: A case study of a Chinese village. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Hu, G.; Li, M.; Yao, Y.; Li, X. An online tool with Google Earth Engine and cellular automata for seamlessly simulating global urban expansion at high resolutions. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 39, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Ma, X.; Chu, Q.; Xie, M.; Cao, Y. Characterizing the Up-To-Date Land-Use and Land-Cover Change in Xiong’an New Area from 2017 to 2020 Using the Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Images on Google Earth Engine. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, L.; O’Neil, A.; Morton, R.; Rowland, C.S. Evaluating Combinations of Temporally Aggregated Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 for Land Cover Mapping with Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanian, A.; Kakooei, M.; Amani, M.; Mahdavi, S.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Hasanlou, M. Improved land cover map of Iran using Sentinel imagery within Google Earth Engine and a novel automatic workflow for land cover classification using migrated training samples. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 167, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Kakooei, M.; Mohseni, F.; Ghorbanian, A.; Amani, M.; Crosetto, M.; Monserrat, O. ELULC-10, a 10 m European Land Use and Land Cover Map Using Sentinel and Landsat Data in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, V.; Deljouei, A.; Moradi, F.; Sadeghi, S.M.M.; Borz, S.A. Land Use and Land Cover Mapping Using Sentinel-2, Landsat-8 Satellite Images, and Google Earth Engine: A Comparison of Two Composition Methods. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, M.; Liu, B.; Yang, X. Analysis of the future land cover change in Beijing using the CA–Markov chain model. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Ning, J.; You, H.; Xu, L. Urban intensity in theory and practice: Empirical determining mechanism of floor area ratio and its deviation from the classic location theories in Beijing. Land 2023, 12, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Yao, Y.; Guan, Q.; Liang, X.; Li, X.; Pan, Y.; Yue, H.; Yuan, Z.; Zhou, J. Simulating urban land use change by integrating a convolutional neural network with vector-based cellular automata. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 1475–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liang, X.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Ou, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Pei, F. A future land use simulation model (FLUS) for simulating multiple land use scenarios by coupling human and natural effects. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 168, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Chen, G.; Yan, Y.; Li, B.; Zeng, L.; Ou, J.; Liu, K.; Liu, X. Simulation of urban land expansion in China at 30 m resolution through 2050 under shared socioeconomic pathways. GIScience Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Mahesh, K.J. Analysing performance of SLEUTH model calibration using brute force and genetic algorithm–based methods. Geocarto Int. 2018, 35, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, X.; Leng, J.; Xu, X.; Liao, W.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. Global projections of future urban land expansion under shared socioeconomic pathways. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, X.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Pei, F.; Xu, X. A New Global Land-Use and Land-Cover Change Product at a 1-km Resolution for 2010 to 2100 Based on Human–Environment Interactions. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 1040–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Shen, S.; Cheng, C.; Dai, K. A hybrid spatiotemporal convolution-based cellular automata model (ST-CA) for land-use/cover change simulation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 110, 102789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhong, Q.; Cheng, D.; Xu, C.; Chang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, B. Landscape ecological risk projection based on the PLUS model under the localized shared socioeconomic pathways in the Fujian Delta region. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, G.; Liu, H. Porter effect test for construction land reduction. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, R.J.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Ford, A.C.; Dawson, R.J. Enhanced urban growth modelling: Incorporating regional development heterogeneity and noise reduction in a cellular automata model-a case study of Zhengzhou, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chang, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Urban expansion simulation under constraint of multiple ecosystem services (MESs) based on cellular automata (CA)-Markov model: Scenario analysis and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Hejazi, M.; Wise, M.; Vernon, C.; Iyer, G.; Chen, W. Global urban growth between 1870 and 2100 from integrated high resolution mapped data and urban dynamic modeling. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Reduction Practices in Coastal Cities under the Background of Reduction: A Case Study of Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Shanghai. Green Environ. Friendly Build. Mater. 2022, 5, 247–249. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hackworth, J. Demolition as urban policy in the American Rust Belt. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 48, 2201–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruehn, D. Regional planning and projects in the Ruhr Region (Germany). In Sustainable Landscape Planning in Selected Urban Regions; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; pp. 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Vaid, U. Delivering the promise of ‘better homes’: Assessing housing quality impacts of slum redevelopment in India. Cities 2021, 116, 103253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnassi, M.; El Haiba, M. Implications of the Russia–Ukraine war for global food security. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubaura, M. Changes in land use after the Great East Japan Earthquake and related issues of urban form. In The 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami: Reconstruction and Restoration: Insights and Assessment After 5 Years; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

| Land Cover Types | 2016 | 2020 | 2024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Testing | Training | Testing | Training | Testing | |

| Construction | 139 | 61 | 140 | 75 | 159 | 61 |

| Farmland | 58 | 27 | 42 | 18 | 36 | 14 |

| Water | 24 | 10 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 13 |

| Forest | 46 | 36 | 41 | 19 | 43 | 37 |

| Grassland | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Bare land | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Variables | Expansion | Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| DEM () | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Distance to airports () | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Distance to centers () | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Distance to lakes () | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Distance to main roads () | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Distance to ocean () | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Distance to ordinary roads () | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Distance to rivers () | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Nighttime light () | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Type | Core Objective | Characteristics | Typical Measures | Representative Districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancement Type | Enhancing Industrial Competitiveness and Urban Functions | Significant trends of expansion and reduction | Industrial Upgrading, land consolidation, and optimization of public services | Chaoyang, Haidian, Tongzhou, Daxing, Shunyi |

| Optimization Type | Decentralizing Non-core Functions and Improving Spatial Quality | Maintain low-level expansion and reduction | Relocation of low-end industries, removal of illegal constructions, and preservation of historical features | Dongcheng, Xicheng, Shijingshan |

| Conservation Type | Prioritizing Ecology and Promoting Sustainable Development | Minor reduction, with a relatively low proportion of expansion | Protecting agricultural and ecological resources and regulating tourism development | Mentougou, Miyun, Yanqing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Meng, X.; Xie, B.; Gao, Y. Spatially Explicit Modeling of Urban Land Consolidation Potential: A New Bidirectional CA Framework for Reduction Planning Implementation. Land 2026, 15, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010063

Liu X, Zhang L, Meng X, Xie B, Gao Y. Spatially Explicit Modeling of Urban Land Consolidation Potential: A New Bidirectional CA Framework for Reduction Planning Implementation. Land. 2026; 15(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xue, Liang Zhang, Xin Meng, Bingqi Xie, and Yukun Gao. 2026. "Spatially Explicit Modeling of Urban Land Consolidation Potential: A New Bidirectional CA Framework for Reduction Planning Implementation" Land 15, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010063

APA StyleLiu, X., Zhang, L., Meng, X., Xie, B., & Gao, Y. (2026). Spatially Explicit Modeling of Urban Land Consolidation Potential: A New Bidirectional CA Framework for Reduction Planning Implementation. Land, 15(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010063