1. Introduction

Over the past decades, a growing body of research has examined how states and regional governance institutions shape industrial upgrading and spatial economic restructuring. Studies on developmental states and regional industrial policy highlight the active role of governments in coordinating investment, infrastructure, and innovation to promote structural transformation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In parallel, spatial planning and economic governance are organized around territorially defined units such as regions, counties, metropolitan areas, and cities, which serve as key platforms for industrial policy and coordination [

5]. As cities are the central locations for capital, labor, and information, urban and regional studies have emphasized the importance of metropolitan regions and city regions as key spatial scales where global production networks, innovation systems, and labor markets are reorganized [

6].

Within this global discussion, empirical evidence on how metropolitan integration policies influence industrial structure upgrading remains relatively fragmented. A body of research examines how transnational economic integration affects industrial upgrading, with a strong geographic focus on Europe. A previous study finds that CEECs have moved into passenger car production, components, and higher value-added activities [

7]. Studies on Asia also point out that Vietnam’s manufacturing firms upgraded product quality in response to ASEAN free-trade arrangements [

8]. These studies highlight the role of cross-border integration, but they mainly operate at the international level. Few studies provide systematic evidence on how state-led metropolitan integration policies reshape urban industrial structures within the domestic context.

China provides a particularly revealing case. Compared with other developing economies, a distinctive feature of China’s industrial upgrading is the strong and persistent role of the state at both the central and local levels [

9]. In this context, the central government promotes regional integration through a series of top-down regional plans and supporting policies, while local governments engage in various forms of inter-jurisdictional cooperation as a bottom-up response to national strategies and cross-boundary challenges [

10]. Metropolitan areas (MAs) have emerged as a key spatial platform for fostering the country’s economic growth. In China, MAs typically evolve within larger urban agglomerations. They represent a form of urbanization centered on megacities, very large cities, or cities with strong economic spillover capacity, usually encompassing areas within approximately a one-hour commuting radius. Existing research indicates that the average economic efficiency of China’s MAs is generally higher than that of urban agglomerations’ broader area [

11]. Development plans for MAs that are formally approved by the National Development and Reform Commission of China (NDRC) constitute the top-level design and programmatic blueprint for the construction of national-level MAs. In February 2019, the NDRC issued guiding policy documents on the cultivation and development of modern metropolitan areas. Since then, the construction of modern MAs has accelerated, and the associated incentive mechanisms and institutional arrangements have been progressively refined. By December 2022, seven national-level metropolitan areas (NMAs) had been officially approved: the Nanjing, Fuzhou, Chengdu, Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan, Xi’an, Chongqing, and Wuhan MAs.

Yet, most empirical studies focus on large-scale urban agglomerations and do not specifically examine the effects of MA integration policies on city-level industrial structure upgrading. MAs are different from urban agglomerations. The core difference lies in the strength and structure of economic ties. Industrial collaboration in MAs far exceeds the relatively loose geographic clustering found in urban agglomerations. Under the current regime of regionalized and localized global value chains, the metropolitan scale is increasingly salient: it places greater emphasis on fostering geographically proximate industrial clusters along specific segments of the value chain, and functions even more explicitly as an “industrial cooperation area” [

12]. MAs clearly reflect agglomeration effects, network effects, and governance coordination, making them valuable for research. However, most existing research focuses on industrial collaboration in broader geographical areas, such as the Yangtze River Delta integration [

13,

14,

15,

16], the Pearl River Delt area [

9], the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region [

17], and other regional agglomerations [

18,

19,

20].

Therefore, this study is motivated by both theoretical and policy considerations. On the one hand, have China’s MA integration policies promoted the upgrading of urban industrial structure? Theoretically, while the literature on developmental states and regional industrial policy stresses the importance of state intervention, there is still limited empirical evidence on how specific metropolitan integration policies affect industrial structure upgrading at a city level. On the other hand, through which mechanisms do these policies operate? Understanding whether, and through which channels, these policies effectively foster upgrading is crucial for evaluating their effectiveness and for informing future regional development strategies. By combining a staggered DID framework with city-level data for Chinese MAs, this paper aims to construct a sound government–market relationship framework, and to fill the existing gap by providing China-based evidence that speaks to broader debates on the role of government in regional industrial transformation. Specifically, the remainder of the paper is organized as follows: (1)

Section 2 defines industrial structure upgrading in a rigorous way, and reviews the relevant literature, thereby providing the theoretical foundation for analysis; (2)

Section 3 develops a conceptual framework along the logic of “policy measures → transmission channels → outcome effects” and proposes testable hypotheses; (3)

Section 4 presents the empirical design and model specification; (4)

Section 5 reports the baseline results, conducts a series of robustness checks, and provides empirical evidence on the proposed mechanisms; (5)

Section 6 discusses the limitations and

Section 7 concludes the main findings and implications.

This study makes four marginal contributions. First, by identifying the impact of MA integration policies on urban industrial upgrading, it provides timely evidence of the role of key spatial policy tools in industrial upgrading. Second, by analyzing and empirically testing the policy transmission mechanisms, it contributes to the theoretical understanding of how MA interacts with industrial upgrading in a developmental state framework. Third, the analysis helps clarify the functional boundaries and complementarities between government intervention and market forces in the process of structural transformation. Finally, it offers policy-relevant insights for fostering a modern regional industrial system and promoting high-quality regional development within a large developing economy.

3. Theoretical Mechanism and Research Hypotheses

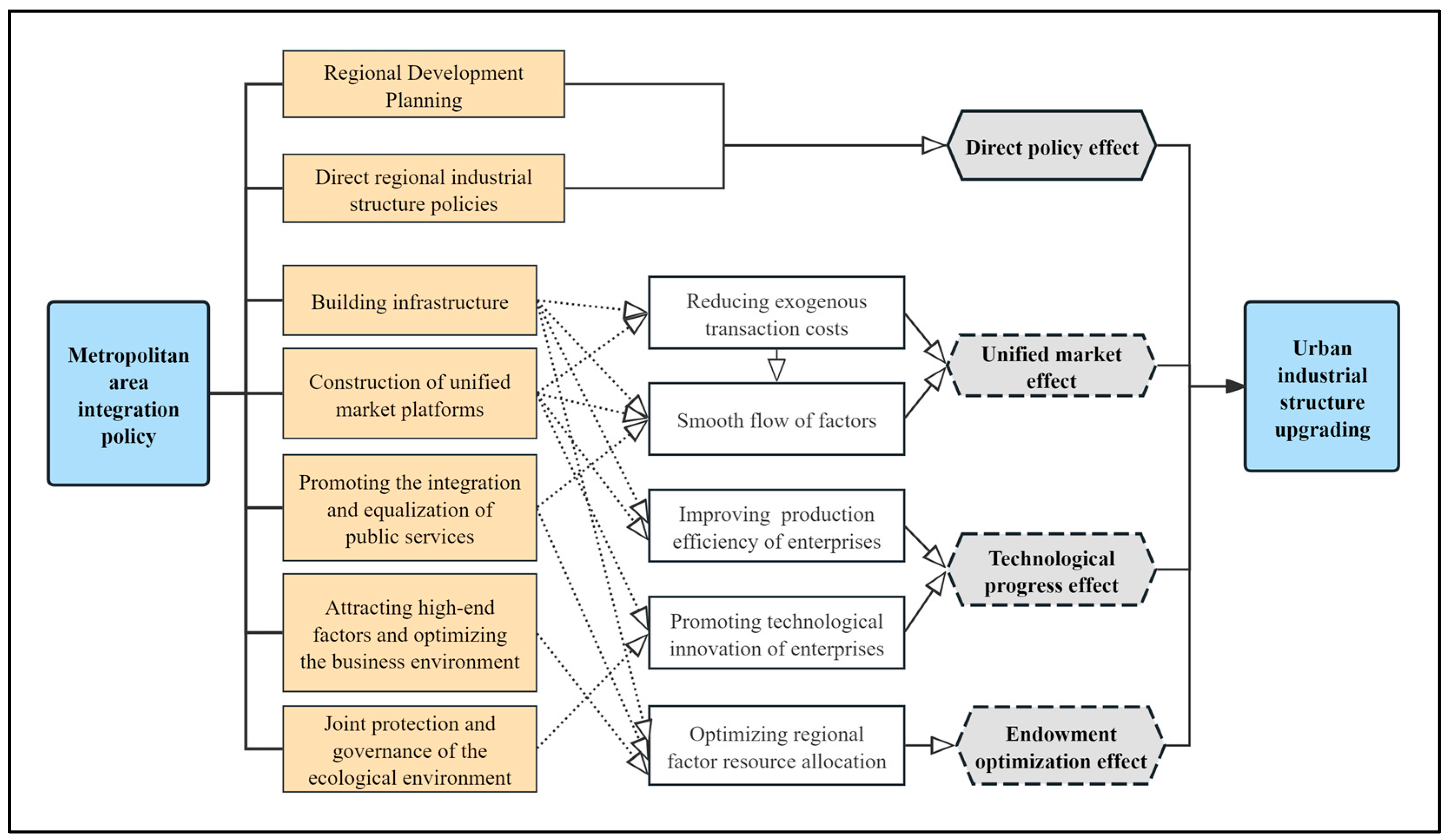

Drawing on the practices of representative Chinese NMAs, we examine how government policies shape industrial upgrading in the process of MA integration policies’ implementation, following the logic of “integrated policies and measures → transmission channels → urban industrial upgrading”. As depicted in

Figure 1, MA integration policies promote urban industrial upgrading through four distinct types of effects.

3.1. Direct Policy Effects

Hypothesis H1: Metropolitan area integration policies effectively promote the urban industrial structure upgrading.

The government directly intervenes in the regional industrial structure by formulating regional industrial development plans and industrial structure policies. Functional industrial policies can, to a certain extent, make up for market failures and reflect the positive role of an effective government [

42]. The direct policy effects are reflected in the following two aspects.

First, government-led regional development plans shape the spatial distribution of industries. In China, MA development plans almost invariably incorporate regional industrial planning, which guides the spatial allocation of industries, specifies requirements for industrial restructuring, sets industrial transformation targets, and provides corresponding implementation mechanisms. The central objective is to construct a spatial configuration that both aligns with regional industrial development needs and enables a rational inter-city division of labor in production factors. In typical MAs, such plans call for industrial patterns characterized by differentiated specialization, cross-regional integration, and coordinated development of emerging and traditional manufacturing; they also emphasize the upgrading of producer services along value chains and the quality-oriented transformation of consumer services. At the same time, they commonly introduce supporting arrangements such as regularized inter-governmental consultations, policy coordination mechanisms, and dedicated organizational structures within the MA.

Second, directly formulating industrial structure policies to guide the upgrading of urban industries during the MA’s construction process. For instance, establishing industrial cooperation parks co-built by central and member cities, relocating traditional production capacities from central cities, and encouraging non-central cities to upgrade their introduced industrial functions, all of them can drive production toward high-value-added segments. For example, by the end of 2023, the “Agreement on the Co-construction of the Nanjing Metropolitan Area Industrial Chain Development Alliance” was signed. In addition, consciously selecting and encouraging the leading industries can lead industrial structure upgrading. In most publicly released “Metropolitan Area Development Plans” in China, nearly all member cities have listed a catalog of key industries for supporting and encouraging development, and the chosen leading industries are generally high-value-added sectors with broad market prospects and representing advanced technology. Meanwhile, when the government identifies leading industries and implements multiple measures to guide them, it also promotes the simultaneous growth of related industries, thus optimizing the industrial structure.

3.2. Indirect Policy Effects

In addition to policies that directly reshape the spatial distribution of industries, typical government interventions during MA integration—such as infrastructure investment, market unification initiatives, efforts to equalize regional public services, measures to attract high-quality production factors, improvements to the business environment, and ecological protection policies—indirectly influence urban industrial upgrading. These interventions give rise to three main types of indirect effects.

3.2.1. Unified Market Effect

Hypothesis H2: Metropolitan area integration policies promote urban industrial structure upgrading through the unified market effect.

Metropolitan area integration is an institutional process that reduces spatial and administrative fragmentation between cities, strengthens inter-city economic linkages, and weakens market segmentation. Through planning, regulation, and policy coordination, governments provide stable signals to firms, guide expectations, and progressively align local rules and standards, thereby laying the foundation for a unified market [

43]. From the perspective of urban and spatial economics, such integration changes the effective economic distance within the MA. Large-scale investment in different kinds of infrastructures, data platforms, and equaled public services compresses communication and coordination costs; while unified rules and interoperable systems reduce institutional frictions. This jointly lowers both iceberg-type trade costs for goods and services, and search and matching costs for factors. Enabling goods, labor, capital, technology, and data to move more freely across city boundaries. As factor flows become more orderly and markets more open within the MA, the formation of a unified regional market is accelerated.

A more unified market, further, reshapes the industrial structure of member cities. Freer factor mobility and improved connectivity facilitate diversified yet interconnected industrial agglomeration, including the co-location of related sectors and upstream–downstream firms. This generates Jacobs-type externalities through finer specialization, easier matching and search, and stronger knowledge spillovers. The vertical and horizontal extension of value chains within the MA fosters new industries and higher value-added activities, thereby promoting the rationalization and upgrading of the industrial structure in member cities.

3.2.2. Technological Progress Effect

Hypothesis H3: Metropolitan area integration policies promote urban industrial structure upgrading through the technological progress effect.

First, under MA integration, improvements in the aforementioned infrastructures can significantly enhance the efficiency of logistics and information transmission, reduce transaction costs while increase enterprise productivity [

44].

Second, the free flow of goods and services on the demand side will eliminate price discrimination in regional commodity market, stimulate greater market demand, and further promote the economies of scale on the supply side, improving production efficiency. At the same time, a more robust competitive environment will force supply-side enterprises to engage in technological innovation.

Third, during MA integration, technological innovation platforms, industry–university–research matchmaking activities, and the cultivation of a favorable business environment and distinctive innovation culture foster technological innovation and support the growth of high-tech start-ups. Governments typically promote the establishment of MA-wide technology transfer alliances, comprehensive technology trading markets, specialized technology property-rights exchanges, and intellectual property markets to advance the formation of a unified technology market. In many MAs, cross-regional digital platforms are developed to integrate innovation resources, value-chain information, and technology policy, enabling firms to identify and access needed innovation resources quickly and accurately.

Finally, China’s MAs are collaborating to manage and protect their regional ecological environments. These policies essentially encourage businesses in these industries to adopt cleaner, more environmentally friendly production technologies, boosting TFP and driving the green transformation of traditional manufacturing. For example, existing industries like steel and cement are undergoing ultra-low emission upgrades, encouraging manufacturers to achieve energy conservation and carbon reduction through clean production and the use of green building materials. Research supports that the Yangtze River Delta Region integrated development could advance technological progress [

15].

How does technological advancement affect urban industrial structure upgrading? The simplified CD production function [

45] can illustrate the principle. For the final product production industry

j, the output at time

t is

where

A represents the technological progress. For any two industries

j or

k, their output

or

and their related shares in the total economy are directly correlated with technological progress

A. Obviously, sectors with faster technological progress growth rates experience higher production efficiency and faster output growth, resulting in a higher share of total output and a more sophisticated industrial structure.

3.2.3. Endowment Optimization Effect

Hypothesis H4: Metropolitan area integration policies promote urban industrial structure upgrading through endowment optimization effect.

MA integration policies can optimize regional factor endowments by formulating talent attraction measures directly, improving public service levels, building computing infrastructures, such as big data or cloud computing centers, enabling industries that intensively use such abundant factors to gain comparative advantages and shifting regional industrial structures towards a more sophisticated one.

First, MA integration constitutes an important mechanism for optimizing the spatial allocation of human capital within regions. In China’s MAs, development strategies increasingly emphasize the attraction and agglomeration of high-end production factors, particularly skilled labor, so as to provide sustained factor support for industrial upgrading. To this end, MA governments typically coordinate human resource information-sharing platforms and harmonize related service policies across jurisdictions, jointly design and implement talent recruitment programs, and promote the mutual recognition of vocational qualifications and standards. These institutional arrangements help to reduce labor mobility barriers within the metropolitan area and facilitate the more efficient matching of human capital with industrial demand.

At the same time, MA integration policies contribute to the equalization and upgrading of regional public services, thereby further enhancing the quality and configuration of human capital. Livability is a core precondition for the sustainable development of local industrial clusters, and integrated policy frameworks can expand the coverage and improve the efficiency of medical, educational, cultural, and leisure services. By enhancing residents’ life convenience and overall well-being, these policies make metropolitan areas more attractive to highly educated and high-skilled workers. The resulting equalization of public services not only improves the regional human resource structure, but also strengthens the metropolitan area’s capacity to retain and cultivate talent. Empirical evidence from the Yangtze River Delta metropolitan region shows that regional integration policies have significantly enhanced the inflow of scientific and technological personnel, thus confirming the positive effect of MA integration on the optimization of regional human capital allocation [

16].

Third, in the era of artificial intelligence (AI), many technology-based firms must process massive volumes of data in real time. Robust computing infrastructure has therefore become essential for supporting advanced digital processing capabilities. MA provides an institutional and spatial platform for strengthening the cross-city allocation and sharing of computing resources. By 2022, several NMA cities—including Wuhu, Chongqing, Chengdu, Wuhan, and Xi’an—had already established large-scale intelligent computing centers or data-center clusters with substantial AI computing capacity. These facilities have been explicitly integrated into MA plans, functioning as shared digital infrastructure that underpins regional AI-related innovation and industrial upgrading.

Overall, according to the Factor Endowment Theory, when the supply of a factor becomes more abundant within a region, the price of goods that intensively utilize that factor decreases. This gives the region a comparative advantage in the production of those goods, and the proportion of those goods in the total output changes. Consequently, the influx of high-end factors, such as talent or data, into a region increases the proportion of high-value-added products in the region’s total output, thereby promoting the upgrading of urban industrial structure.

5. Regression Results

5.1. Balance Test

Following Gentzkow (2006) [

52] and Li et al. (2016) [

53], we examine the changes in the differences between metropolitan cities and non-metropolitan cities after adding control variables

in

Table 3. The balance test results for each variable are shown in

Table A2.

Firstly, we select cross-sectional data of 2012, the beginning of the window period, to analyze statistical characteristics of the two groups of cities. Columns (1) and (2) in

Table A2 are the means of each variable or indicator for the two groups. Columns (1) and (2) reveals that, on average, MA member cities outperformed non-MA cities in five aspects: population density (lnpop), per capita income (lngdppc), foreign direct investment (lnfdi), traffic, and transportation condition (lntrans); meanwhile, the comparison of lngovfin shows that the fiscal deficit scale of MA governments is smaller than that of non-MA cities, indicating members’ relatively healthier government fiscal situation. Cities within MAs are more likely to be the economically developed cities in their respective provinces and are more likely to actively participate in regional coordinated development policies. So, it is necessary to control the

series variables.

Furthermore, we choose consumer market size and population mobility to represent urban differences. As can be seen in

Table A2, in 2012, the mean of the consumer market size index for MA cities was 6.47, and the mean logarithmic population mobility rate was 3.32, both higher than those for non-MA cities. The unconditional difference results in column (3) also show that there are indeed differences between the two groups of cities in the two urban characteristics. After controlling for

, the conditional difference estimation results in column (4) show that there are no longer differences between the two groups of cities in the two characteristics. It is evident that before controlling

for member cities, there are significant differences between MA cities and non-MA cities in both two indicators; after adding

as control variables, the two urban characteristics no longer show significant differences between the two groups (as shown in column (4)). Therefore, the paper, by selecting appropriate base period characteristic control variables

, makes the treatment and control groups more balanced in terms of economic characteristics, which provides support for subsequent empirical analysis.

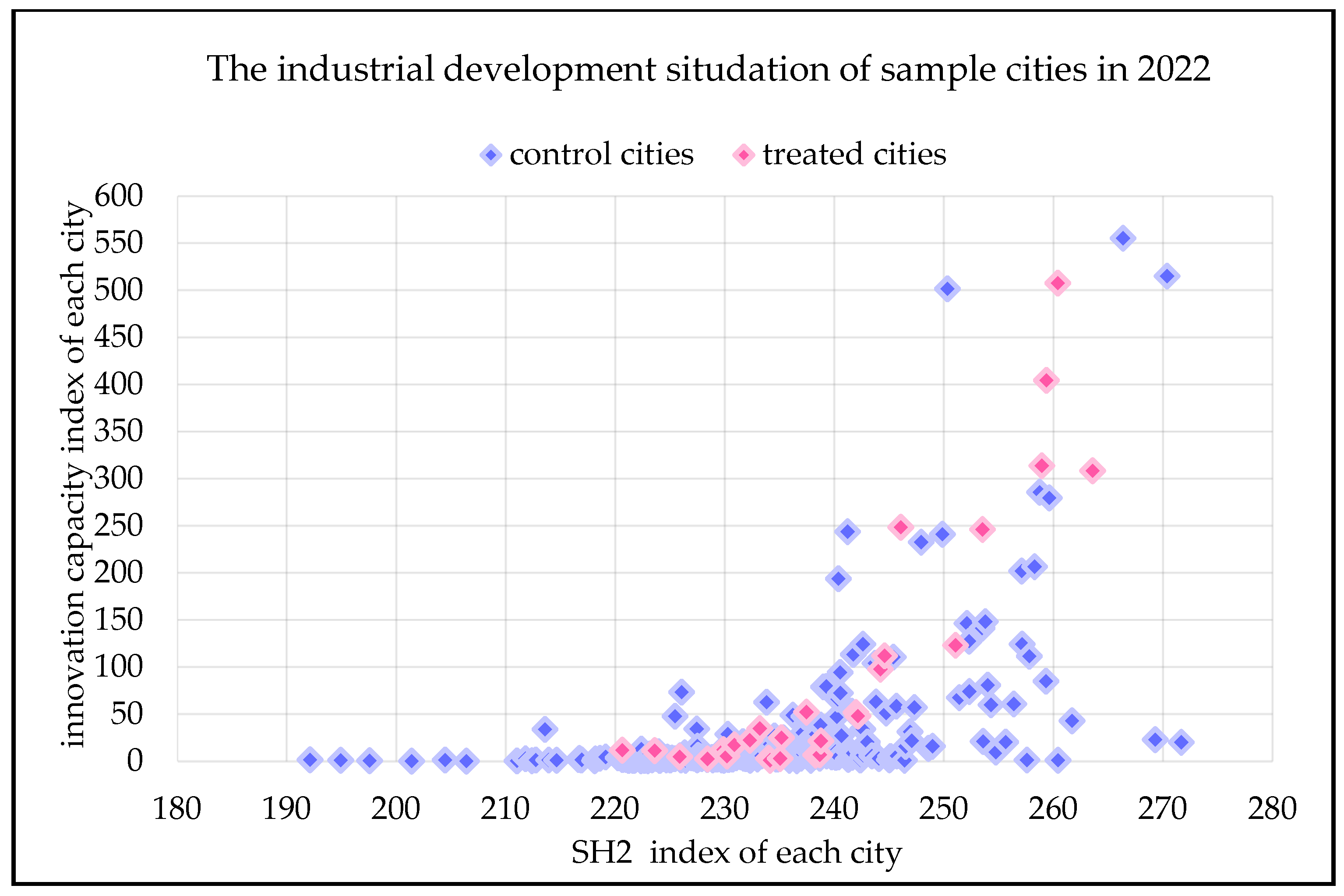

5.2. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 4 below shows descriptive statistics of the independent and dependent variables. The mean values of the high-level index SH1 and SH2 for the 3091 samples are 1.11 and 231.51, respectively. For SH2, the minimum value of the high-level index is 183.12 in Heihe City, Heilongjiang Province, in 2012, and the maximum one is 283.59 in Beijing, the capital of China, in 2022. For the independent variables, taking lnpop as an example, the minimum lnpop value 1.628 is obtained in Jiuquan City, Gansu Province, in 2012, and the maximum value 8.1 is obtained in Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, in 2022.

5.3. Benchmark Regression

The staggered DID model of the impact of China’s MA integration policies on urban industrial structure upgrading, that is, the estimation results of Equation (1) are shown in

Table 5. From a national perspective, even if different measurement methods are used, whether it is SH1 or SH2 high-level index, the impact of the exogenous policy shock of MA integration policies on the industrial structure upgrading of MA member cities is significantly positive at the 1% level, and the R

2 value is above 0.9. Column (2) shows that the high-level degree of industrial structure of metropolitan area member cities is about 2.43 percentage points higher than that of non-MA cities. In addition, by using “entrepreneurial activity (lnenter_act)” as a substitute dependent variable (outcome variable), which indicates industrial vitality and innovation, column (3) shows that entrepreneurial activity in cities within MAs is 8.28% higher than that in non-MA cities.

Although the estimated effect of 2.43 may appear small in magnitude, it has clear economic significance for two main reasons. First, the standard deviation of the 3091 observations over the 11-year period is 14.187. On this basis, 2.43 amounts to nearly one-fifth of a standard deviation, implying a nontrivial impact both statistically and economically. Second, SH2 is a structural, weighted indicator with low elasticity and strong inertia, and is therefore inherently less volatile. Even changes at the second decimal place typically reflect several years of cumulative structural adjustment. Structural indicators are “sticky” and difficult to alter in the short run: the shares of the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors are constrained by existing industrial capacity, capital accumulation, and labor allocation. Unlike GDP growth, SH2 behaves more like a “physical” measure, where even a small shift signals a meaningful reallocation of resources. Moreover, for any given city, a one-percentage-point increase is quite demanding. Once a city’s industrial structure has reached a relatively advanced level of servicification, further improvements require substantial net expansion in high-end services, advanced manufacturing, R&D activities, and headquarters-based functions.

These jointly prove the Hypothesis H1: Metropolitan area integration policies promote the urban industrial structure upgrading.

5.4. Robustness Checks of the Model

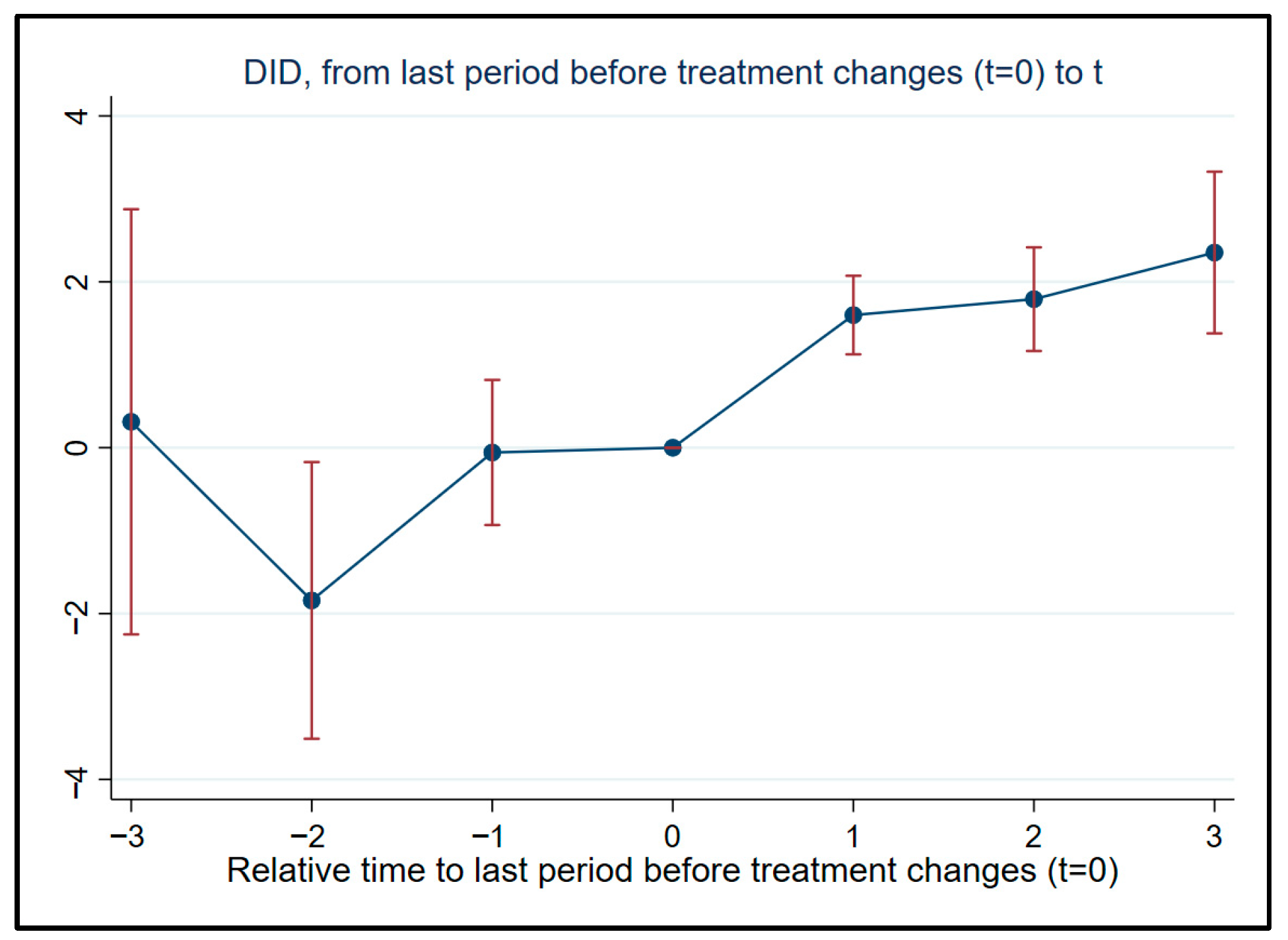

5.4.1. Parallel Trend Test Result

The specific estimation coefficients of Equation (3) are shown in

Figure 4, where the coefficients of the variables almost equal zero before the treatment, and the current or the post coefficient are not zero, significantly. Meanwhile, by conducting a parallel trend test for the dependent variable

, the estimated F-value also shows that the null hypothesis that the pre-treatment coefficients are jointly zero cannot be rejected, indicating that the parallel trend assumption is satisfied.

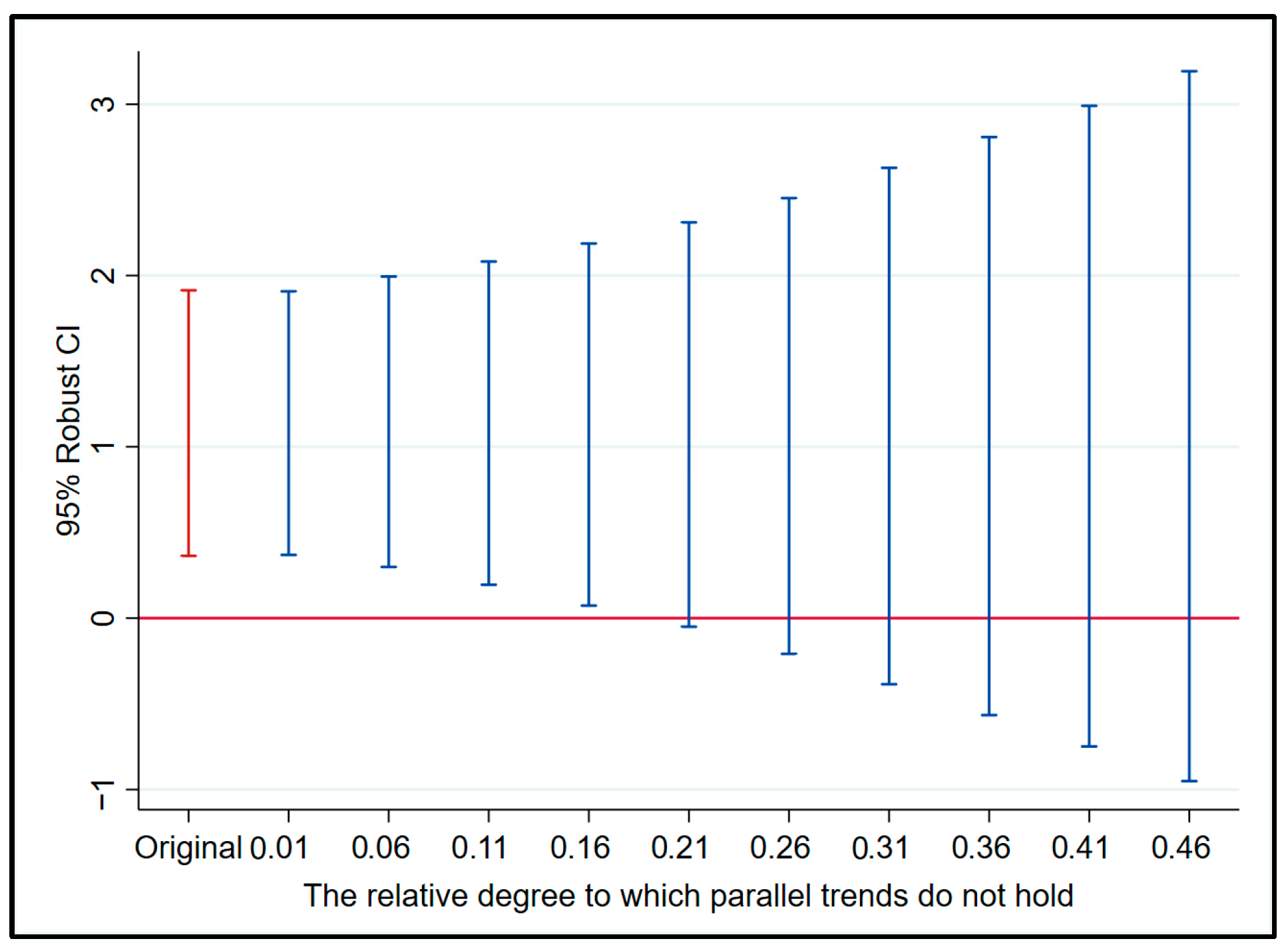

5.4.2. Parallel Trend Sensitivity Analysis

It has become common practice to assess the plausibility of the parallel trend assumption by testing for pre-treatment differences in trends (“pre-trends”). Although pre-trend tests are intuitive, recent research has shown that they may suffer from low power. Rambachan and Roth (2023) [

54] propose a method to examine the impact of the degree of violation of the parallel trend hypothesis on the event study point and confidence interval. To test the “parallel trend hypothesis”, we should conduct both a “pre-trend test” and a “post common shock test”.

Section 5.4.1 has already completed the former, and we should go on conducting a parallel trend sensitivity test to verify the post-treatment parallel trend by adopting this method. By using the concept of relative deviation, sensitivity analyses on the current period 0-year lag, 1-year lag, and 1- and 2-year lags’ average are conducted.

The results of treatment effect are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure A1, respectively. In

Figure 5a: the leftmost “original” (red vertical line) on the horizontal axis represents the average treatment effect of CSDID (will be fully explained in subsequent robustness tests); the blue lines that follow represent the confidence intervals of the current treatment effect when the parallel trend deviates by 0.01, 0.06, 0.11, and 0.16 times, respectively. From

Figure 5a, we can see that even if the parallel trend after treatment deviates by about 0.11 times, the MA policies still have a significantly positive effect on urban industrial structure upgrading at the 95% confidence interval. Similarly, in

Figure 5b, the blue line indicates that when the parallel trend deviates by 0.015 times, the average treatment effect over the two periods after treatment is still significantly positive. The parallel trend sensitivity test is passed.

5.4.3. Robustness Checks

Heterogeneity Treatment Effect Test

Traditional staggered DID estimation can be taken as a weighted average of multiple treatment effects, where the weights may be negative. However, negative weights can lead to a discrepancy between the average treatment effect and the actual one, resulting in biased estimation. A multi-period dual robust estimator “Callaway and Sant Difference-in-Differences” (CSDID) has been proposed [

55]. The core idea of the CSDID method is to divide the sample into different subgroups, estimate the treatment effect of each subgroup separately, and then calculate the average treatment effect (ATT) of different subgroups by using a specific strategy. This method helps to avoid the problem of traditional DID estimation bias.

We employ CSDID as a strategy to enhance the robustness of the results and address concerns about potential bias in the two-way fixed effects estimation (TWFE). The CSDID estimation results for SH2 are as follows: Simple ATT is 0.883, dynamic ATT is 0.934, calendar-time ATT is 0.789, and group ATT is 0.902. All four methods yielding ATTs are significant at the 1% level. The relative results are shown in

Figure 6. Similar results are obtained when SH2 is replaced with lnenter_act. This demonstrates the robustness of the above benchmark regression conclusions.

Placebo Test

Based on the principle of falsification, and using the placebo test method, we further investigate whether the baseline estimation model is confounded by omitted variables or unobservable factors. Using Stata 17 software simulation, individuals are randomly sampled from the sample without replacement to form a “pseudo-treatment group” sample of the same number. Staggered DID estimation is performed, and this process is repeated 500 times. The distribution of the estimated placebo effect coefficients is shown in

Figure 7: the baseline regression result of the variable SH2, 2.4285, is an extreme value in the density distribution plot, with a

p-value less than 0.01 (see the position of red solid line). The null hypothesis that the treatment effect is zero in the baseline regression is rejected. In addition, by randomly varying the treatment group and using spurious policy shock times to estimate the spurious regression coefficients, the result of probability density distribution is similar. The benchmark regression is robust.

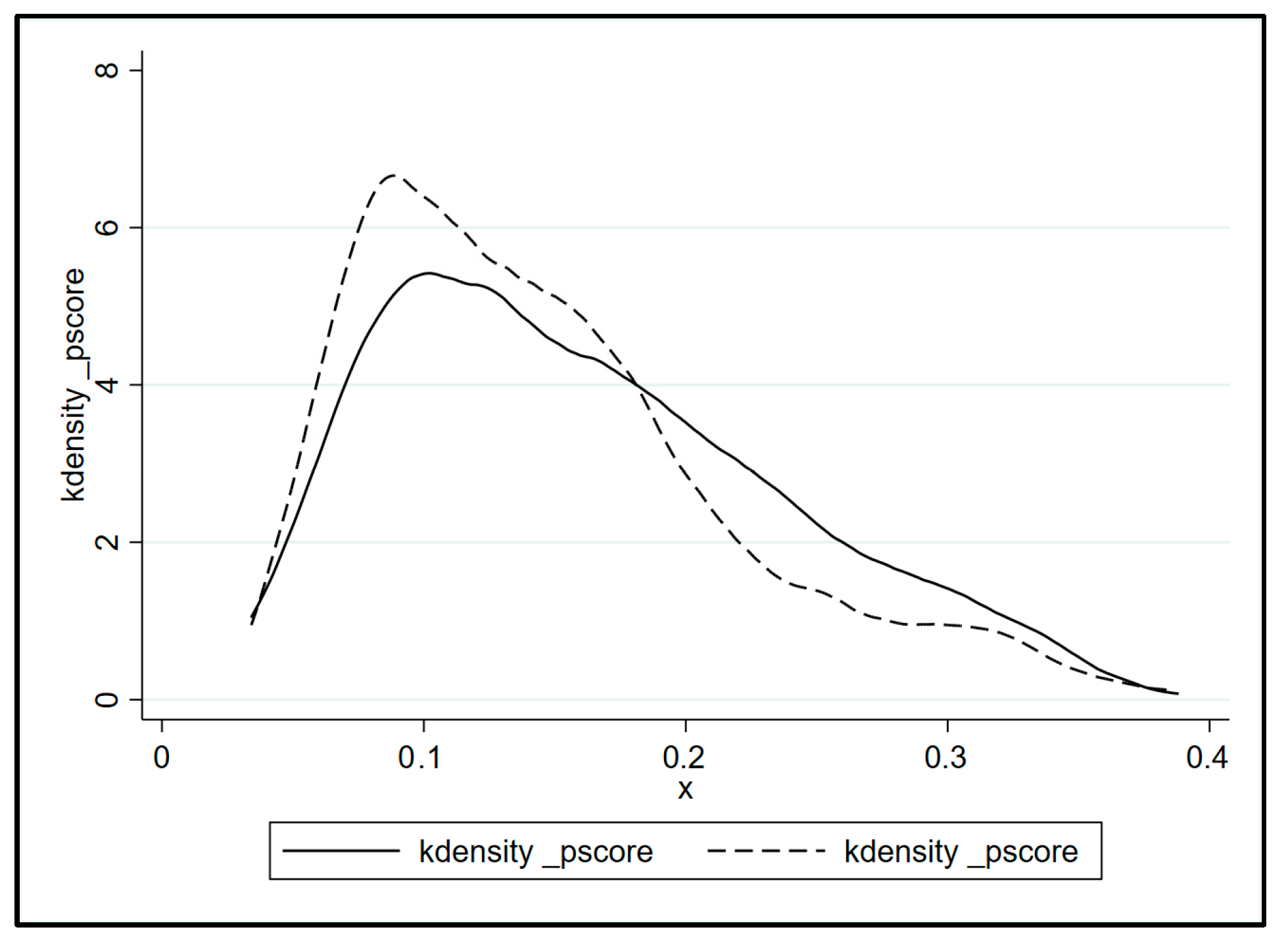

PSM-DID Test

We employ propensity score matching (PSM) to preprocess and match the data, enabling the construction of a well-defined control group and ensuring that the treatment and control groups are comparable in terms of their initial endowments and macroeconomic environment. Thus, ensuring the parallel trend assumption of the DID model holds true as much as possible.

After matching, 759 samples are off-support, 2332 samples are on-support, and the relative probability density distribution can be seen in

Figure 8. Using the 2332 on-support samples to estimate Equation (1), the results are as follows: 1.7324 of SH2 (significant at the 1% level), with an R

2 value of 0.9578, and 0.053 of SH1 (significant at the 5% level). They are consistent with the benchmark regression results, indicating a relative robustness.

Truncation Test

To prevent extreme values from interfering with the benchmark estimate, we perform a 5% truncation of the explained variable SH2. By removing samples with extremely small values below the 5th percentile and samples with extremely large values above the 95th percentile, the remaining samples are used to re-estimate Equation (1), resulting in an estimated value of 2.3693 (significant at the 1% level). The truncation results are similar to the benchmark regression, also demonstrating the robustness of the original estimation.

Controlling Time-Trend Term

Finally, we control for the time-trend term in the original model (Equation (1)) to see if the estimated results change, thus eliminating the influence of natural objective time trends on the estimated net policy effect. This eliminates the influence of time trends on the industrial structure upgrading effect of the MA integration policies in member cities. After controlling for the time-trend term, the re-estimated result is 2.3531 (significant at the 1% level), with an R2 of 0.9482, consistent with the baseline estimation.

5.5. Mechanism Test Results

The empirical results of the mechanism (H2-H4) test are shown in

Table 6. We should note that mechanism analysis only reflects the association between variables, not the causal relationship. The results show that the MA integration policy promotes industrial structure upgrading through the effects of unified market, technology progress, and endowment optimization. The specific results are as follows:

(1) Unified market effect

. The columns of

Table 6 shows that the regression coefficients of the market_inte, lnpflow, and lninfra variables are all positive and pass the significance test. This reveals that the MA integration policies have a positive impact on the upgrading of the industrial structure of member cities through channel

. In detail, the policies can reduce transaction costs by promoting factor mobility (lnpflow) as well as infrastructure connectivity (lninfra), and improving the unification level of regional market (market_inte).

(2) Technological progress effect

.

Table 7 presents the estimation results of the policies’ effect on promoting technological progress. In columns (2), (3), (5), and (6), the footnotes 1 and 2 indicate invention patents and utility model patents, respectively. Controlling for innovation capacity (lninnova), all estimated coefficients are significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the MA integration policies significantly promote technological progress for MA cities.

However, two points are noteworthy. First, the coefficient for green patents (0.6069, column 4) is significantly lower than the coefficient for total patents (3.9205, column 1). Second, no matter at both the total patent or green patent aspects, the regression coefficient for invention patents is smaller than that for utility models: the value in column 2 (1.4884) is much smaller than that in column 3 (4.5669); the comparison results in columns 5 and 6 are similar. These two points reveal that the MA integration policies have a limited effect on technological progress in member cities, and they may only promote general technological advancement, rather than cutting-edge technology.

(3) Endowment optimization effect . The lnhc variable’s coefficient is 0.1315, positive at the 5% significant level. This indicates that the implementation of MA integration policies can attract an influx of high-quality labor. It can be proved that endowment optimization is an effective way for MA integration policies to influence the urban industrial structure upgrading.

6. Discussion

This section interprets the main empirical findings in light of the existing literature, draws out their practical and policy implications, and then outlines the study’s limitations and directions for future research.

6.1. Comparison with Existing Literature and Mechanism Insights

The results show that, relative to non-MA cities, the level of industrial sophistication in MA member cities increases by about 2.43 percentage points following MA integration policies. This provides quantitative evidence that MA integration polices can meaningfully accelerate industrial upgrading within a relatively short time frame. Such findings are broadly consistent with prior studies emphasizing the role of regional integration in facilitating structural transformation through larger markets, improved factor mobility, and enhanced knowledge diffusion in both developed and developing contexts [

13,

14,

18,

19,

23,

24,

25,

27,

32,

33,

34,

35]. At the same time, by focusing on China’s newly established national-level MAs and their “industrial collaboration circles” feature, this study extends the literature by examining a more formalized and institutionally dense type of metropolitan integration.

Beyond the average treatment effect, the mechanism analysis indicates that MA integration policies promote industrial upgrading primarily by fostering a more unified regional market, advancing technological progress in a broad sense, and optimizing factor endowments. These channels resonate with existing work on regional industrial policies [

36,

37]. However, our study underscores that these channels are actively shaped by coordinated governmental action at the metropolitan scale. In this regard, the evidence highlights the important role of a capable and coordinated government in urban and regional industrial governance.

At the same time, the findings reveal an important nuance: while MA integration policies are effective in promoting “broad” technological progress, their impact on frontier technological upgrading in member cities remains modest. This pattern aligns with concerns in the innovation policy literature that large-scale regional coordination efforts often prioritize infrastructure connectivity, factor mobility, and general industrial collaboration, while providing comparatively weaker, less stable, and less targeted support for high-risk, long-horizon R&D [

38,

39,

40,

41]. In addition, substantial differences in research capacity, industrial structure, and fiscal strength among cities within the same MA can hinder the formation of robust collective mechanisms for supporting frontier innovation. Taken together, the results suggest that MA integration, in its current institutional form, is better at facilitating incremental, diffusion- and transformation-type upgrading than at catalyzing breakthroughs at the frontier technological fields.

6.2. Practical and Policy Implications

The empirical results have several implications for the design and implementation of MA integration policies. First, the fact that market integration, broad-based technological progress, and factor endowment optimization emerge as central mechanisms implies that these dimensions should be treated as core objectives in MA policy frameworks. In practical terms, this calls for further dismantling administrative and market segmentations between cities and provinces, improving the interoperability of regulatory systems, and deepening the integration of labor, capital, and other key factor markets within MAs.

Second, the organizational role of MAs as platforms for industrial cooperation and functional specialization should be further utilized. Beyond formal designation, MAs can be used to coordinate the division of labor along industrial chains, the spatial layout of key functional platforms, and the siting of major industrial projects, so as to facilitate the orderly agglomeration and diffusion of high-end manufacturing and modern services within metropolitan regions. This is particularly important in China’s central and western regions and in small or medium-sized urban agglomerations, where selectively fostering a number of MAs with strong diffusion and driving capacities can be an important instrument for promoting coordinated regional development and enhancing these regions’ positions within national value chains.

Third, the limited impact of current MA policies on frontier technologies suggests the need for more targeted arrangements to support high-end innovation. Policymakers in MAs should promote the development of integrated innovation communities built around cross-regional joint laboratories, collaborative innovation centers, and shared industrial technology institutes. Stronger inter-city arrangements for cost- and benefit-sharing are needed, together with more coherent rules for intellectual property protection and technology transfer. In addition, differentiated tax incentives, talent policies, and financial instruments can be designed to guide innovation resources to cluster and circulate more efficiently within MAs, thereby providing more effective support for frontier technologies. Nevertheless, the role of policy in this regard should be understood primarily as enabling and coordinating, rather than directly determining specific technological trajectories. Breakthroughs in frontier technologies ultimately depend on the endogenous innovation incentives of firms and research institutions.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Building on the above findings, this study still has several limitations, which also suggest directions for future research.

First, the post-treatment observation window is relatively short. In terms of data structure, the post-treatment period is relatively short, which may not allow sufficient time for industrial structure upgrading to fully materialize. As time passes, the post-treatment window will gradually extend, and newly released data can be used to track and reassess the dynamic impacts of MA integration policies.

Second, the measurement of the outcome variable remains relatively coarse. The construction of the outcome variable yit is somewhat crude. Due to data availability constraints, the study relies on a three-sector classification, which is not sufficiently detailed and limits the economic interpretability of the SH index series. Future research should adopt more disaggregated industrial classification schemes and develop more refined SH-type indicators to capture industrial upgrading at a deeper level.

Third, concerns about policy endogeneity cannot be fully eliminated. As a regional policy instrument, MA integration is not exogenously or randomly assigned. Instead, it is closely linked to local governments’ development strategies, cities’ economic foundations, existing industrial structures, and prior growth paths. Cities with stronger economic bases, more urgent upgrading pressures, and greater governance capacity are more likely to be included in early batches of MA approvals, which may introduce selection bias. This study mitigates endogeneity concerns by incorporating city-fixed effects, year-fixed effects, and a range of city-level control variables, as well as by conducting multiple robustness checks. Nevertheless, the possibility of “selective establishment” of MAs cannot be completely ruled out. Future research should make better use of differentiated pilot designs, exploit more granular policy thresholds, or apply stronger exogenous instrumental variables to improve identification of the quasi-causal effects of MA integration policies.

Fourth, externalities and spatial spillovers are not explicitly examined. The analysis focuses on how MA integration policies affect industrial upgrading within member cities, but it does not directly assess the implications for neighboring non-member cities. In principle, integration policies may generate positive spillovers by enlarging regional markets, accelerating technology diffusion, and facilitating factor mobility, potentially inducing passive or follow-up upgrading in adjacent areas. At the same time, a “siphoning effect” cannot be ruled out: high-end factors and high-quality industries may become more concentrated within MAs, thereby compressing the upgrading space of neighboring non-member cities. Future research should investigate these heterogeneous spillover mechanisms across different types of MAs and city tiers, ideally at a more refined spatial scale. Linking city-level analyses with firm- or plant-level data would also help to evaluate more comprehensively the distributional and welfare consequences of MA integration policies, including their effects on regional equity and overall efficiency.

Finally, despite efforts to explore potential mechanisms, the current design of mechanism variables remains somewhat limited. In particular, the measurement of endowment optimization relies mainly on human capital resource-related indicators, which just capture one important channel highlighted in the existing literature. Other relevant dimensions, such as capital and data resource supplies, are not explicitly modeled due to data constraints. Future research should incorporate a richer set of mechanism variables to provide a more comprehensive test of the theoretical framework.

7. Conclusions

This study makes an innovative contribution by taking China’s newly established national-level metropolitan areas (NMAs)—which began to emerge around 2021 and have since expanded rapidly—as the empirical setting. Exploiting the new institutional feature of “industrial collaboration circles”, we treat MA integration as a quasi-natural experiment and employ a staggered DID framework to estimate the impact of MA integration policies on industrial upgrading in 281 prefecture-level cities. The empirical analysis confirms that MA integration policies significantly enhance industrial sophistication in member cities, thereby enriching the theoretical understanding of regional governance in large developing economies.

The findings can be summarized in three main points. First, MA integration policies lead to a substantial improvement in the industrial sophistication of member cities, with an average increase of about 2.43 percentage points relative to non-MA cities. Second, the analysis suggests that this upgrading effect operates mainly through three channels: the creation of a more unified regional market, the promotion of broad-based technological progress, and the optimization of factor endowments. Third, while MA integration policies are generally effective in promoting structural upgrading, current policy frameworks still provide only limited support for frontier technological innovation.

Overall, the results imply that MA integration policies can serve as an important institutional vehicle for coordinated regional development and urban industrial upgrading, provided that they continue to reduce market segmentation, facilitate technology diffusion, and optimize the allocation structure of high-end production factors, while paying greater attention to sustained and targeted support for frontier innovation.