Topological Structure Characteristics of Ecological Spatial Networks and Their Correlation with Sand Fixation Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area Overview

| Category | Indicator | Typical Value/Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Geographic extent | 113.81° E–116.08° E, 40.73° N–42.18° N | |

| Total area | 17,226.83 km2 | ||

| Topography | Elevation range | 857–2176 m | |

| Dominant landforms | Undulating plateau and low hills | ||

| Climate | Climate type | Temperate continental steppe climate [38] | |

| Mean annual precipitation | 387.35–400 mm [36] | ||

| Mean annual evaporation | 1637 mm [36] | ||

| Average temperature of the four seasons | Spring, 4.8 °C; summer, 17.8 °C; autumn, 4.0 °C; winter, −11.7 °C [39] | ||

| Prevailing wind | Northwest (winter/spring) [35] | ||

| Vegetation | Major vegetation types | Stipa steppe, artificial shelterbelts (Populus and Ulmus), crops [37] | |

2.2. Data Sources and Pre-Processing

2.3. Methodological Framework

2.4. Construction of the ESN

2.4.1. Identification of Ecological Sources

2.4.2. Construction of Ecological Resistance Surface

2.4.3. Construction of Ecological Corridors

2.5. Complex Network Topological Structure Indices

2.5.1. Degree and Degree Distribution

2.5.2. Closeness Centrality

2.5.3. Betweenness Centrality

2.5.4. PageRank

2.5.5. Clustering Coefficient

2.5.6. Coreness

2.6. Calculation of Sand Fixation Capacity

2.6.1. The Climatic Factor ()

2.6.2. The Soil Erodibility Factor ()

2.6.3. The Soil Crust Factor ()

2.6.4. The Soil Roughness Factor ()

2.6.5. The Vegetation Factor ()

2.7. Correlation and Regression Analysis Between Network Topology and Sand Fixation Function

3. Results Analysis

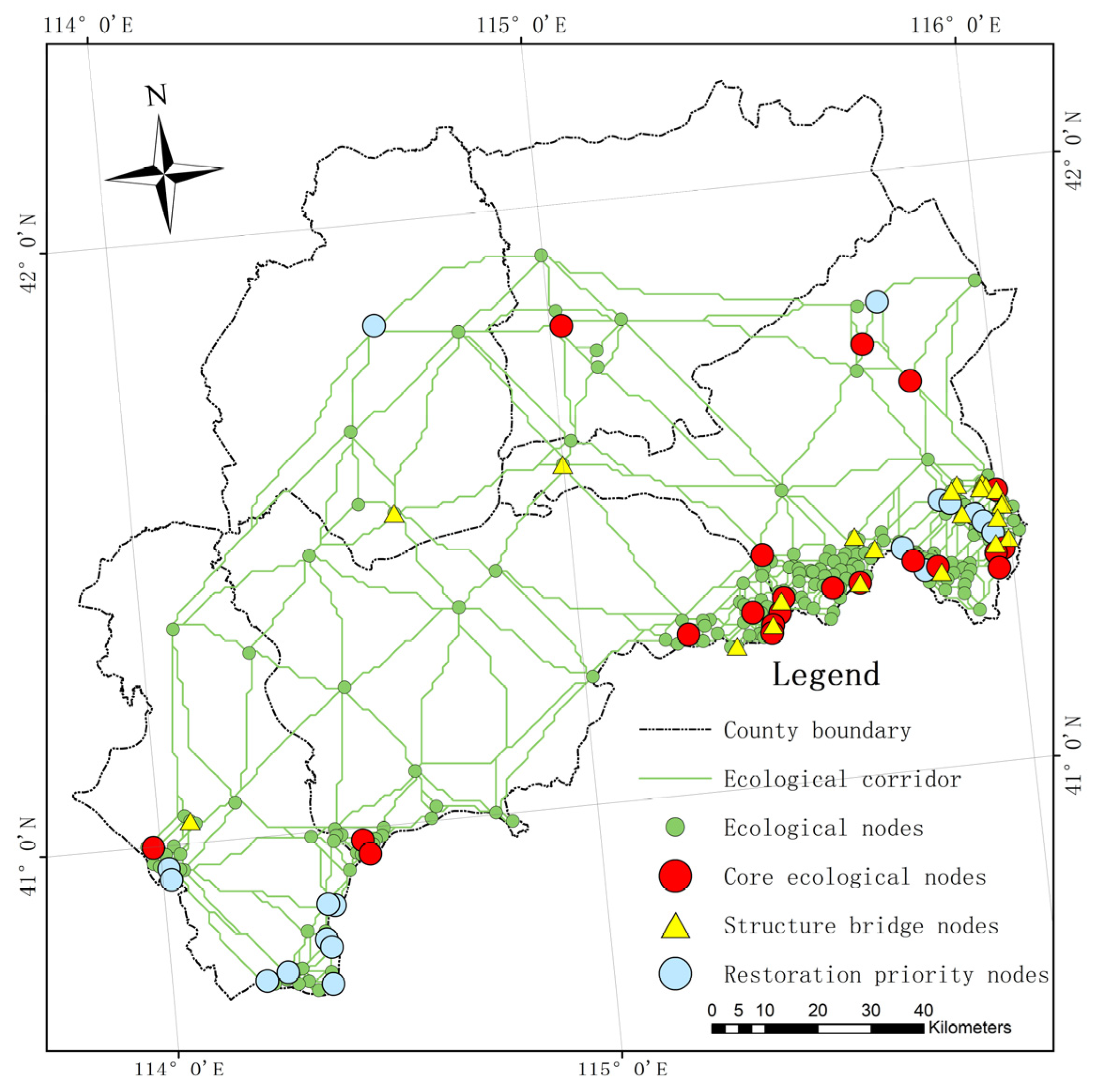

3.1. Construction of the ESN

3.1.1. Construction of the Ecological Resistance Surface

3.1.2. Screening of Ecological Source Areas and Extraction of Ecological Corridors

3.2. Topological Structure Characteristics of the ESN

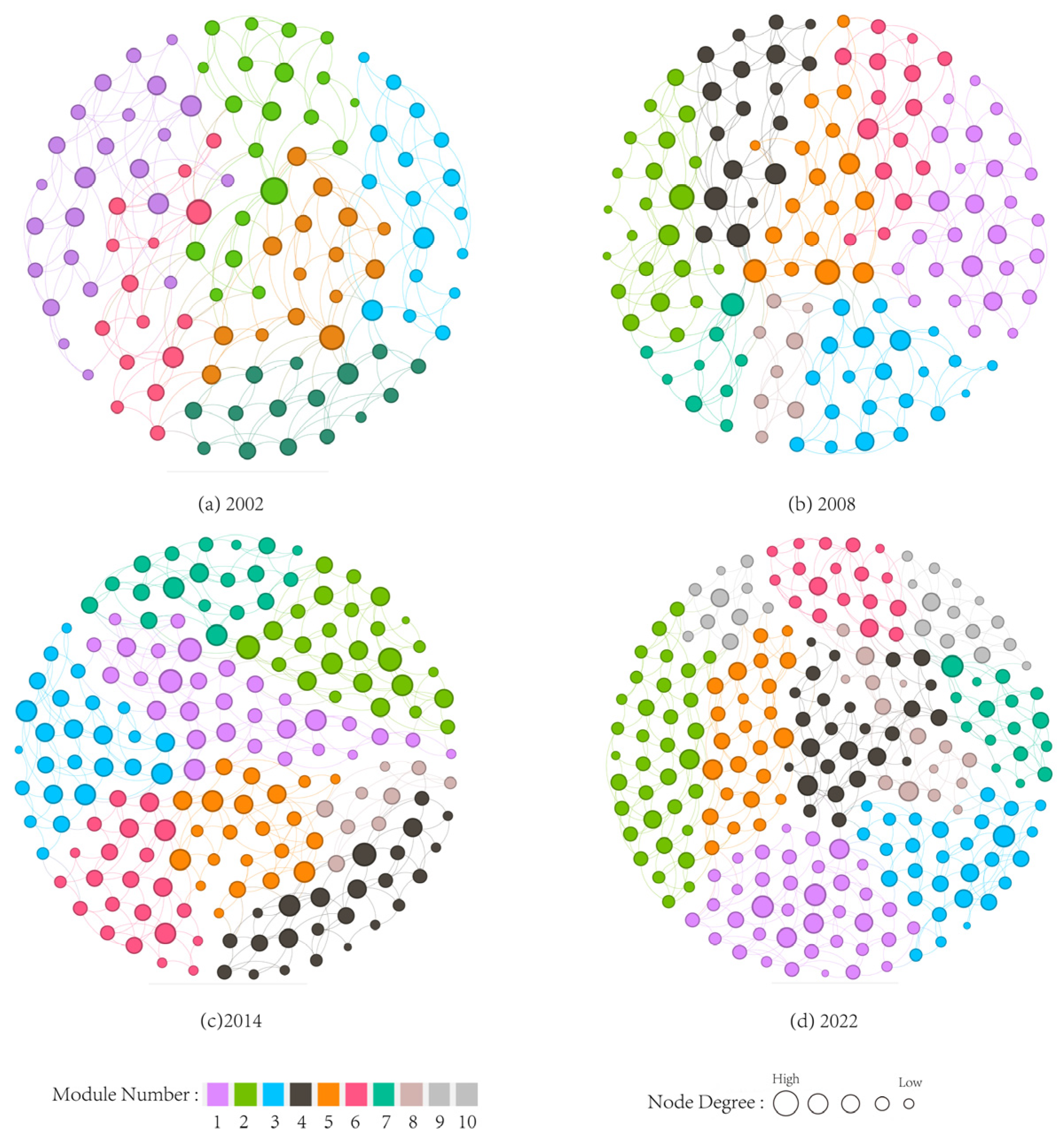

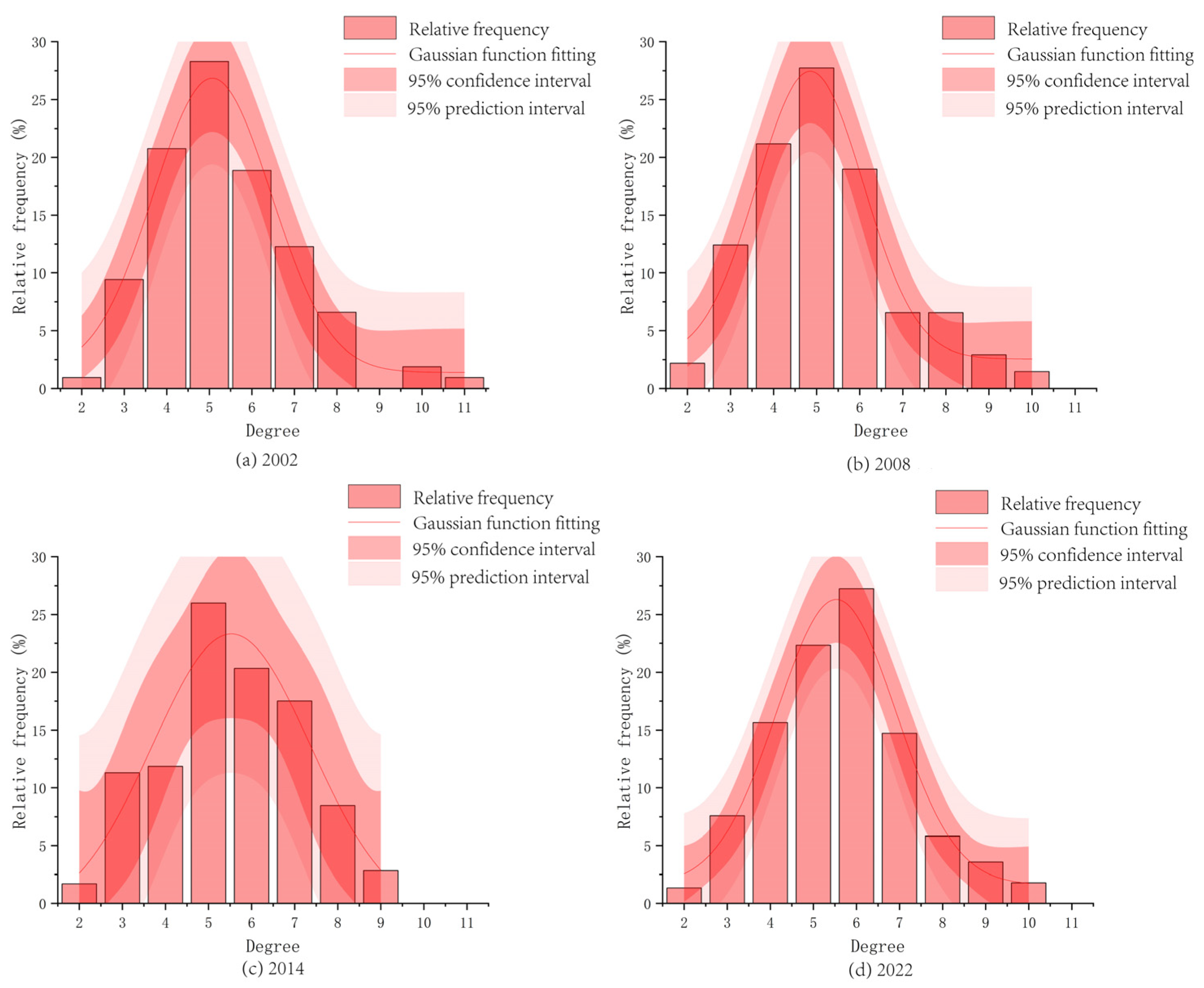

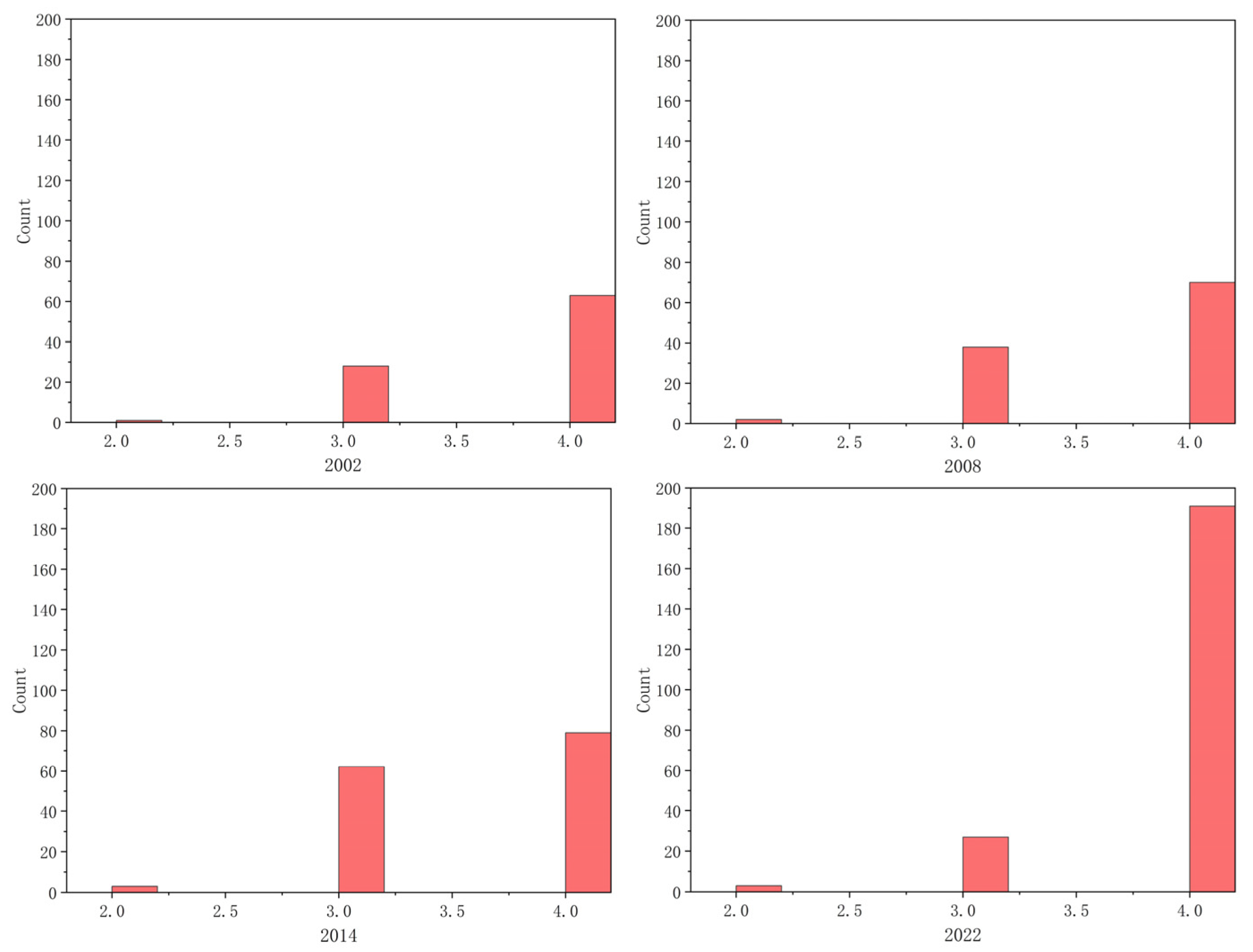

3.2.1. Degree and Degree Distribution

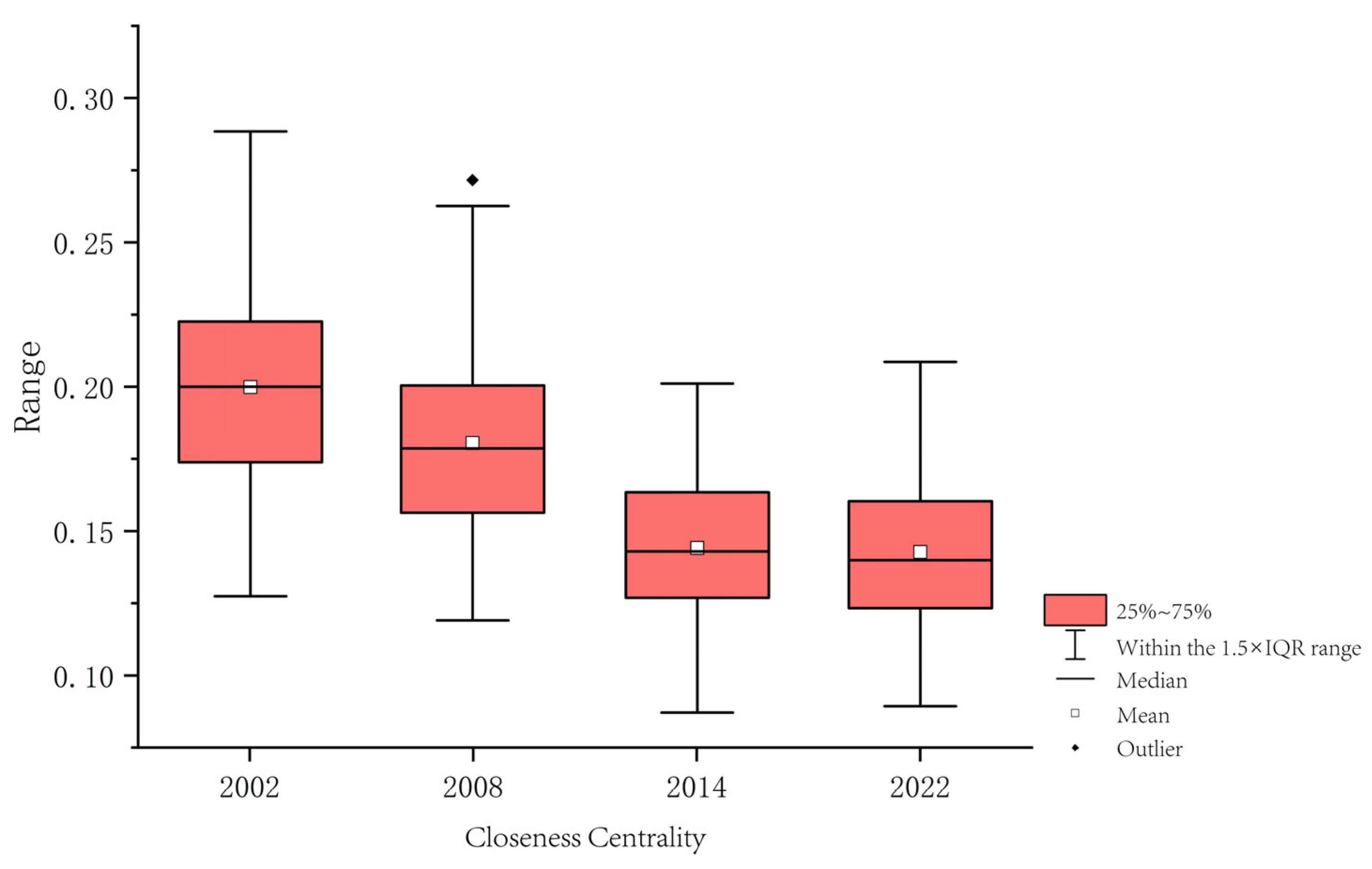

3.2.2. Closeness Centrality

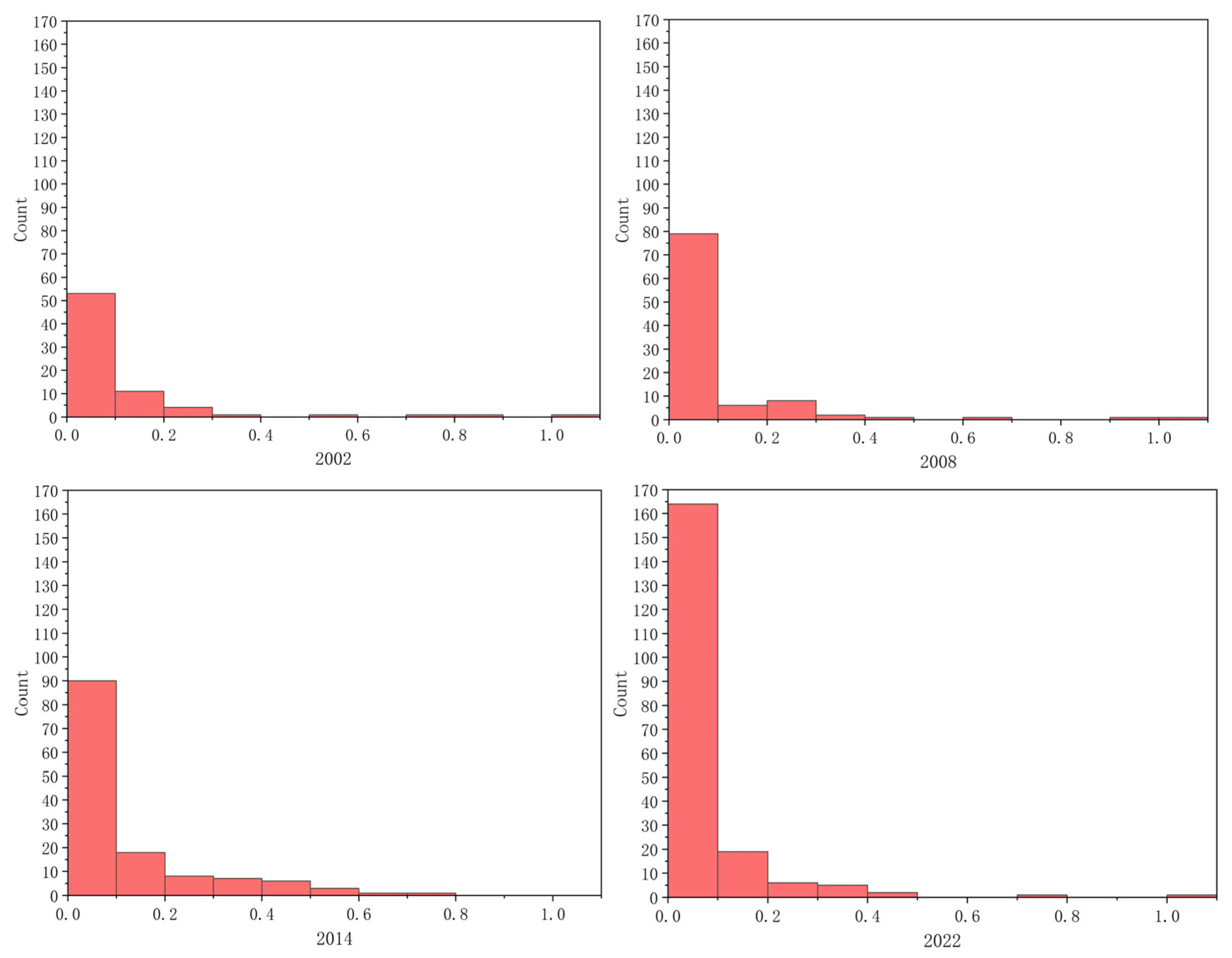

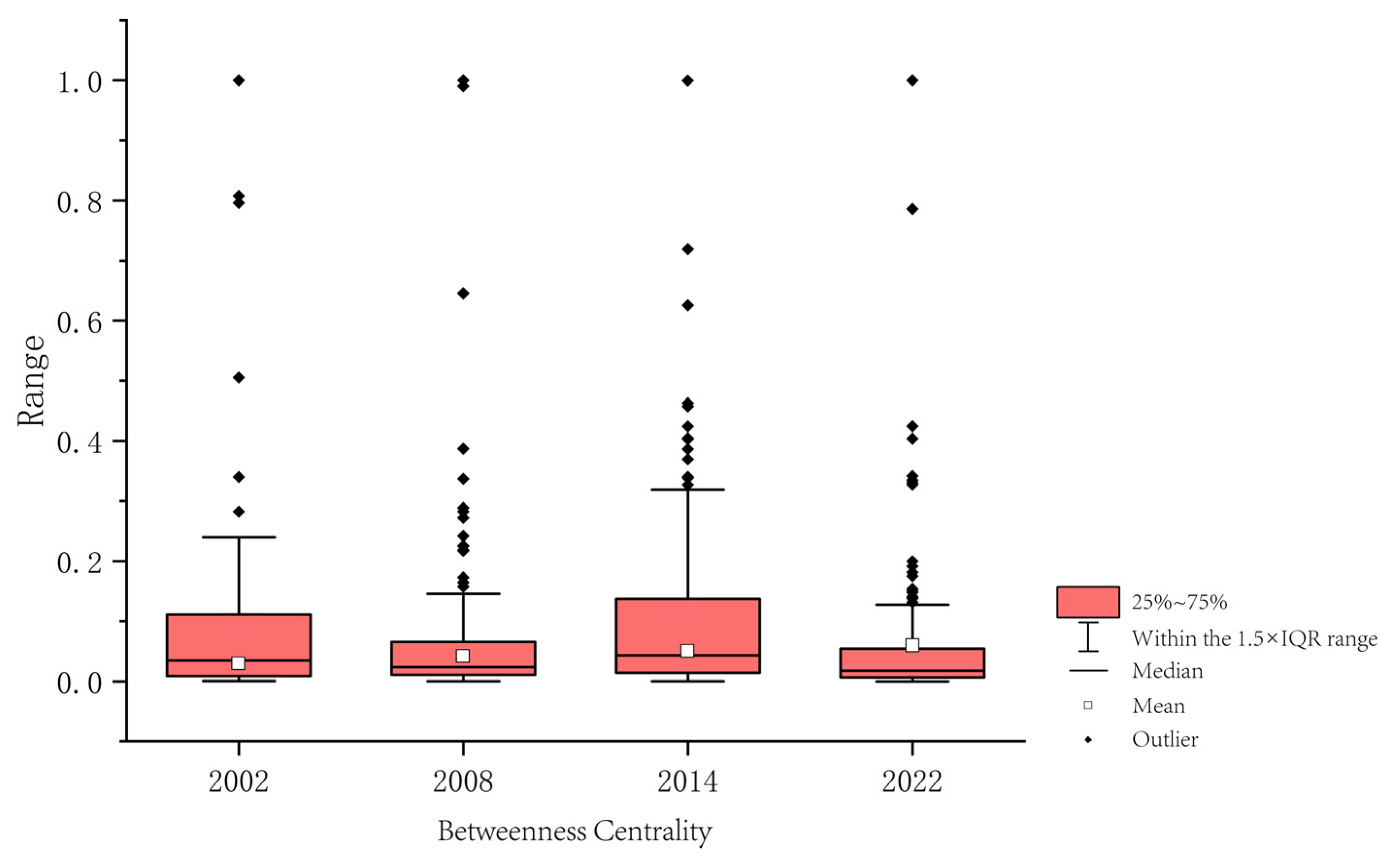

3.2.3. Betweenness Centrality

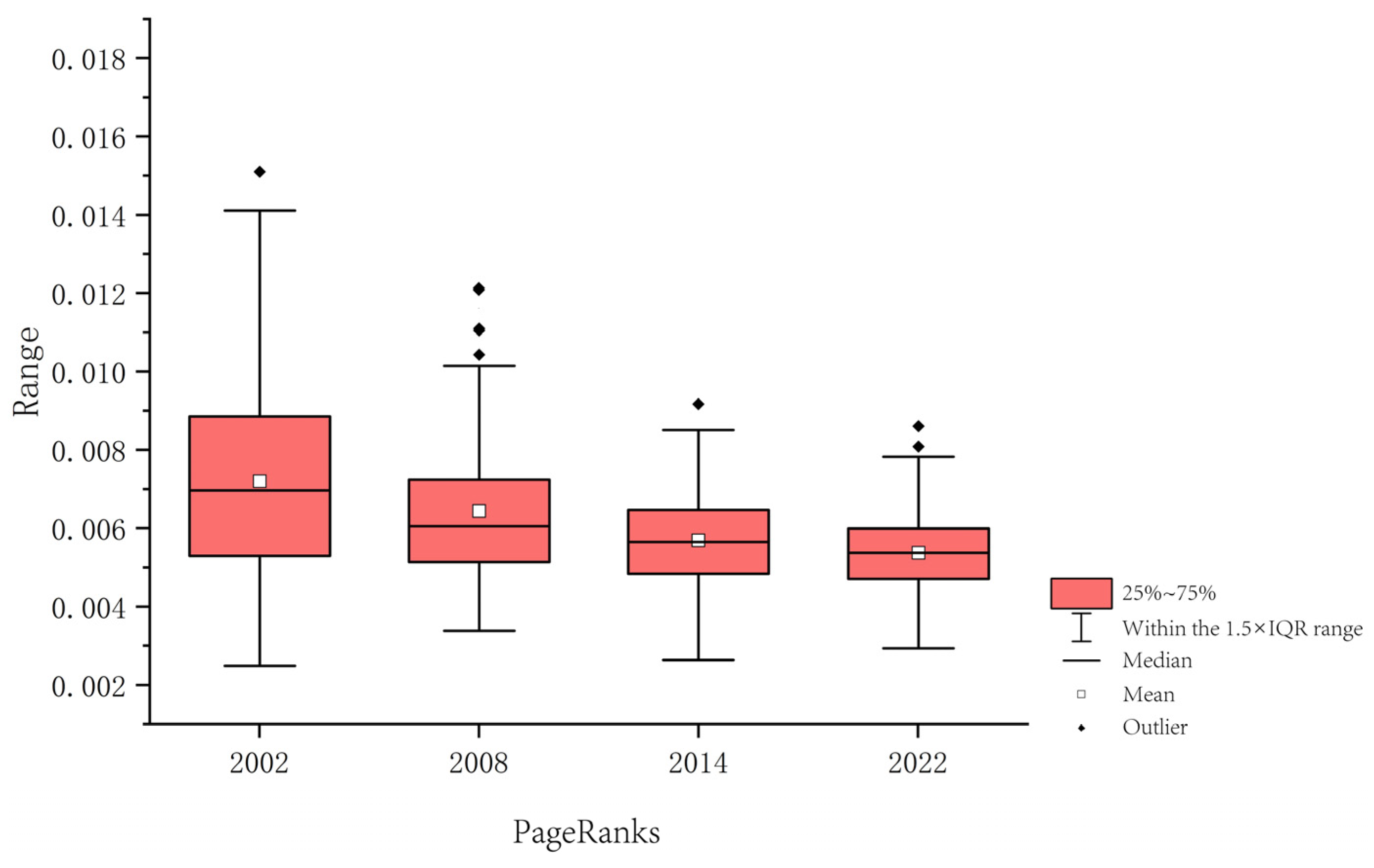

3.2.4. PageRank

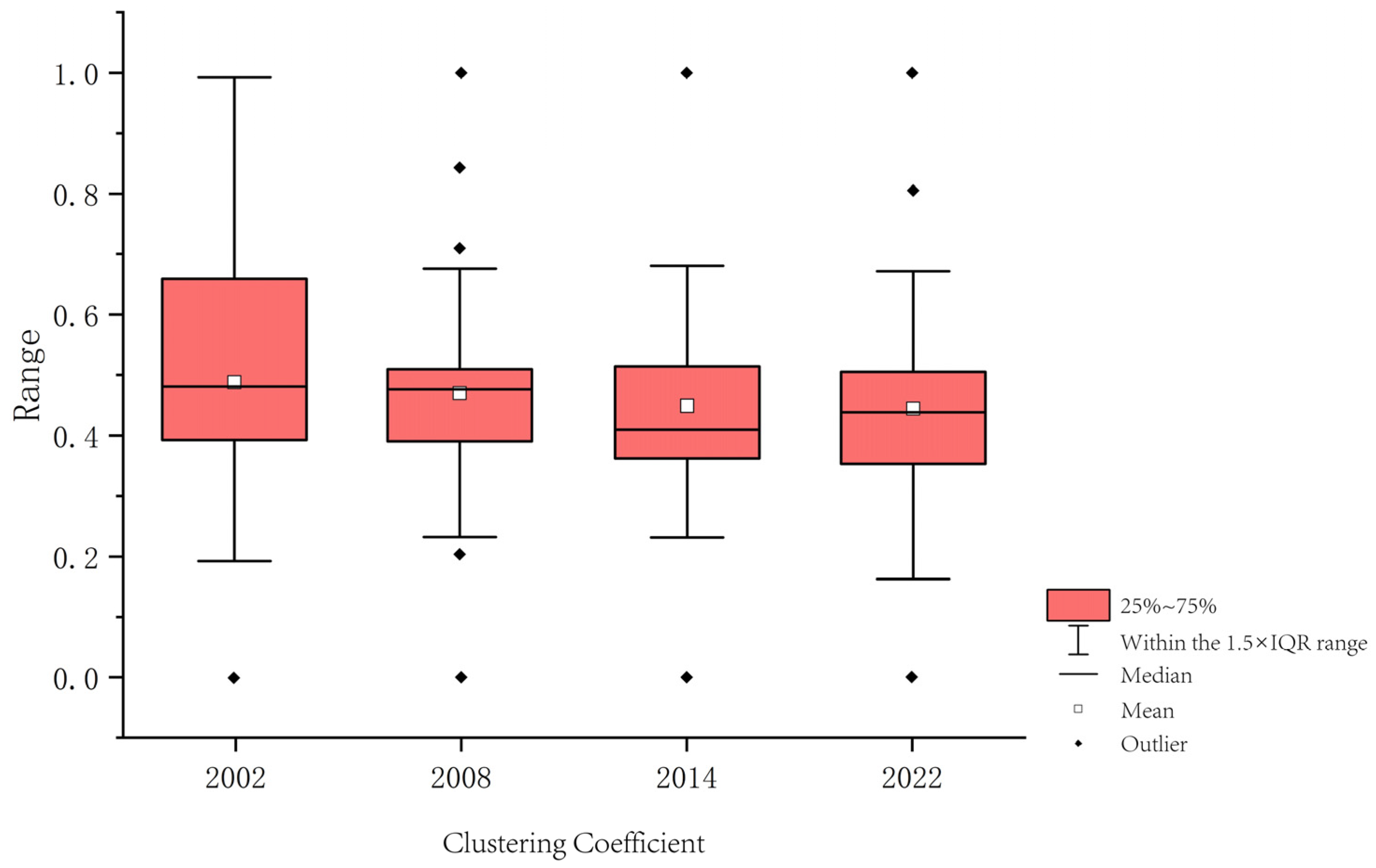

3.2.5. Clustering Coefficient

3.2.6. Coreness

3.3. Sand Fixation Function

3.3.1. in Zhangbei Region

3.3.2. in Zhangbei Region

3.3.3. in Zhangbei Region

3.3.4. of Ecological Source Areas

3.4. Relationships Between Topological Characteristics of Ecological Nodes and Wind Erosion

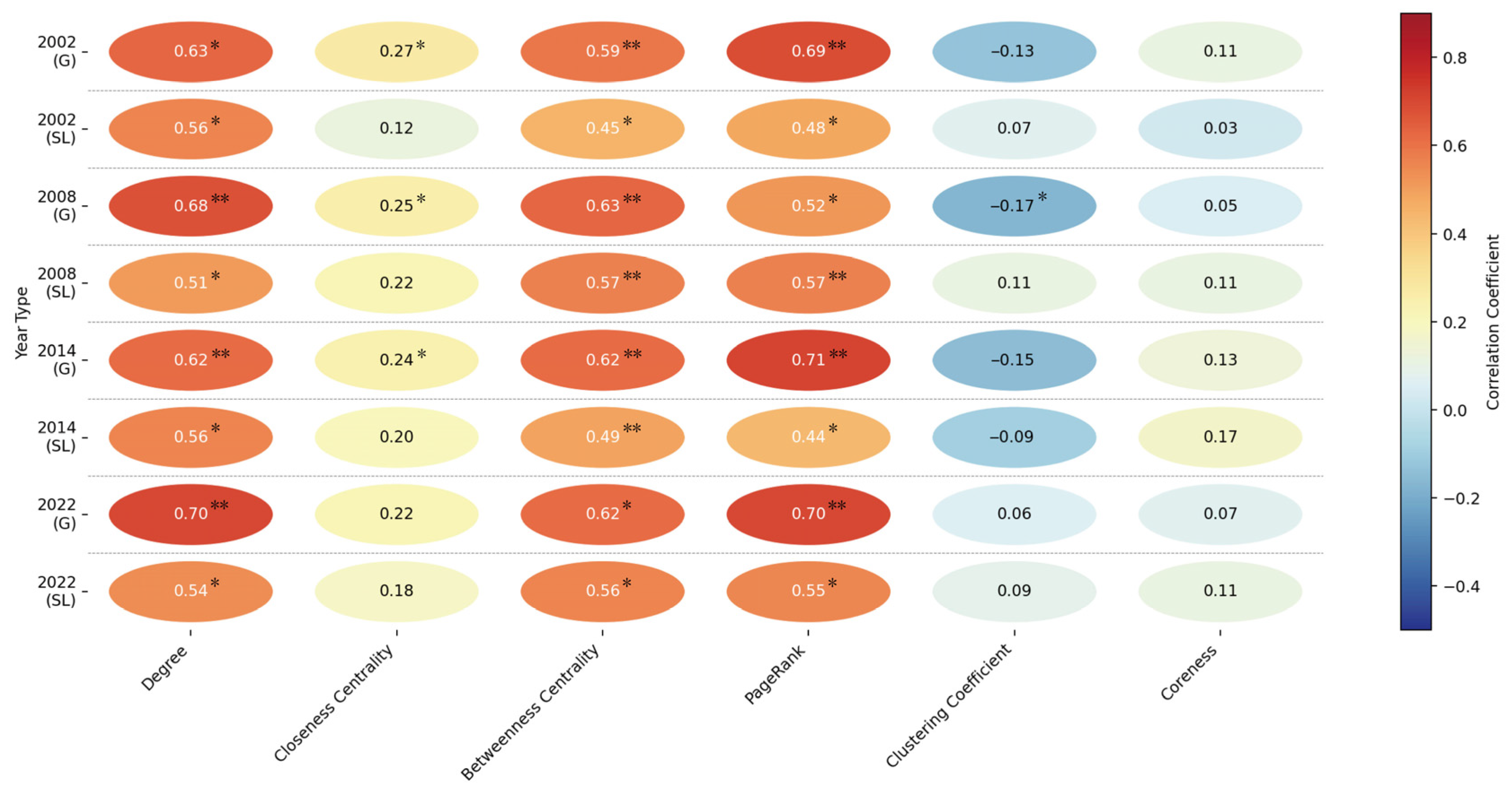

3.4.1. Correlation Between Topological Characteristics and Wind Erosion

3.4.2. Regression Analysis of the Effects of ESN Topology on Sand Fixation Capacity

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Evolution of the ESN and Sand Fixation in Zhangbei

4.1.1. Overall Structural Pattern and Temporal Changes

4.1.2. Regional and Temporal Comparisons with Other Arid–Semi-Arid Regions

4.2. Relationship Between Topological Structure Characteristics and Sand Fixation Function

4.3. Implications for Restoration Planning and Ecological Corridor Design

4.3.1. Prioritizations of Strategic Nodes and Modules

4.3.2. Edge-Adding Strategies and Practical Constraints

4.3.3. Integration with Existing Programs and International Assessment Frameworks

4.4. Uncertainties, Spatial Autocorrelation, and Limitations

4.4.1. Model and Parameter Uncertainties

4.4.2. Data Resolution and Remote-Sensing-Based Indicators

4.4.3. Spatial Autocorrelation and Unmodeled Drivers

4.4.4. Limitations in Network Metrics and Temporal Resolution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Opdam, P.; Steingröver, E.; van Rooij, S. Ecological networks: A spatial concept for multi-actor planning of sustainable landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Du, Y.; Meersmans, J.; Qiu, S. Linking ecosystem services and circuit theory to identify ecological security patterns. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Yu, Q.; Niu, T.; Fang, M.Z.; Guo, H.Q.; Liu, H.J.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.Y. Restoration and Renewal of Ecological Spatial Network in Mining Cities for the Purpose of Enhancing Carbon Sinks: The Case of Xuzhou, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, Y.; Polasky, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Rao, E.; et al. Improvements in ecosystem services from investments in ecological conservation. Science 2016, 352, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Lü, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, W. Ecosystem service assessment for the Gobi Desert region of China based on Landsat images. J. Arid Environ. 2016, 130, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff, N.P.; Siddoway, F.H. A wind erosion equation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1965, 29, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryrear, D.W.; Bilbro, J.D.; Saleh, A.; Schomberg, H.; Stout, J.E.; Zobeck, T.M. RWEQ: Improved wind erosion technology. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2000, 55, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, L.J. A wind erosion prediction system to replace the wind erosion equation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1991, 46, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, H.; Sharratt, B.; Feng, G.; Lei, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, Z. Validation of WEQ and RWEQ for estimating soil wind erosion in the transition zone between desert and steppe. Aeolian Res. 2017, 29, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Knaapen, J.P.; Scheffer, M.; Harms, B. Estimating habitat isolation in landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1992, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soille, P.; Vogt, P. Morphological segmentation of binary patterns. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2009, 30, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, B.H.; Dickson, B.G.; Keitt, T.H.; Shah, V.B. Using circuit theory to model connectivity in ecology, evolution, and conservation. Ecology 2008, 89, 2712–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, M. Integrating ecosystem services and jagged terrain to identify ecological security patterns in the Loess Plateau. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122365. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wu, J.; Gong, J.; Li, S. Human footprint in Tibet: Assessing the spatial barriers to antelope migration routes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa Ayram, C.A.; Mendoza, M.E.; Etter, A.; Pérez-Salicrup, D.R. Habitat connectivity in biodiversity conservation: A review of recent studies and applications. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2016, 40, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischendorf, L.; Fahrig, L. On the usage and measurement of landscape connectivity. Oikos 2000, 90, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba Hernández, R.; Camerin, F. The application of ecosystem assessments in land use planning: A case study for supporting decisions toward ecosystem protection. Futures 2024, 161, 103399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, S.; Rubio, L. A common currency for the conservation planning of nature reserve networks: The probability of connectivity. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 539–549. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, P.; Chen, W.; Hou, Y.; Li, Y. Linking ecosystem services and ecosystem health to identify ecological risk control zones in the Tianshan North Slope Economic Belt. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13745. [Google Scholar]

- Zeller, K.A.; McGarigal, K.; Whiteley, A.R. Estimating landscape resistance to movement: A review. Landsc. Ecol. 2012, 27, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Si, G.; Yu, Q.; Huang, H.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Guo, H. Study on the Relationship between Topological Characteristics of Vegetation Ecospatial Network and Carbon Sequestration Capacity in the Yellow River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, T.; Ansari, M.G.I.; Avirmed, B.; Zhao, T.; Liu, W.; Lian, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, X.; et al. Ecological network optimization and its correlation with net primary productivity in the Thal Desert: A 20-year analysis. Geospat. Inf. Sci. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Chen, L.; Gong, H. Soil and water conservation and sand-fixing engineering and vegetation restoration in China. Ecol. Eng. 2007, 30, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, D.; Keitt, T. Landscape connectivity: A graph-theoretic perspective. Ecology 2001, 82, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö.; Norberg, J. A network approach for analyzing spatially structured populations in fragmented landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galpern, P.; Manseau, M.; Fall, A. Patch-based graphs of landscape connectivity: A guide to construction, analysis and application for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö.; Saura, S. Ranking individual habitat patches as connectivity providers: Integrating network analysis and patch removal experiments. Ecol. Model. 2010, 221, 2393–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, E.; Bodin, Ö. Using network centrality measures to identify landscape connectivity complex. Ecol. Complex. 2008, 5, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Liu, M.; Zhuang, D.; Melillo, J.M.; Zhang, Z. China’s changing landscape during the 1990s: Large-scale land transformations estimated with satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, in press. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Kan, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, G.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, W. The Effects of Multi-Scenario Land Use Change on the Water Conservation in the Agro-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China: A Case Study of Bashang Region, Zhangjiakou City. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration (NFGA). The Beijing-Tianjin Sandstorm Source Control Project has Achieved Remarkable Results: A “Green Great Wall” Safeguarding Beijing and Tianjin. 2021. Available online: https://www.forestry.gov.cn/c/www/zxdt/42365.jhtml (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Zhan, X.K.; Yan, B.Z.; Yu, Y.B.; Tuo, Y.P.; Xie, X.D. Ecological Environment Vulnerability Assessment of Typical Agro-Pastoral Ecotone: A Case Study of Zhangbei County, Bashang, Zhangjiakou. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2025, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H.; Zhang, X. Ecological sensitivity analysis of tourist highway based on GIS: Taking the east line of Zhangbei grassland road as an example. J. Hebei Inst. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2024, 42, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A.B.; Chen, F.G.; Zhao, Y.X.; Qin, Y.J.; Shen, H.T.; Liu, X. Dynamic evaluation of ecological environment quality and analysis of influencing factors in the northern agro-pastoral ecotone: A case study of Bashang Area in Hebei Province. J. Shanxi Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 44, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Y. Spatial and Temporal Variation of Soil Erosion in Typical Water-Wind Erosion Ecotone in North China—Take Zhangjiakou City as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Yaan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, X.J.; Wang, W.; Chen, D.; Huang, X.; Yang, J. Comprehensive Assessment and Analysis of Natural Resources and Ecological Conditions in the Zhangbei Area. Remote Sens. Nat. Resour. 2025, 37, 164–172. [Google Scholar]

- Tianqi24. Zhangbei Historical Weather [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.tianqi24.com/zhangbei/history.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Shen, W.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, Y. China Regional 250m Normalized Difference Vegetation Index Data Set (2000–2023) [DB/OL]; National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, A.; Reuter, H.I.; Nelson, A.; Guevara, E. Hole-Filled Seamless SRTM Data V4 [EB/OL]; CGIAR-CSI SRTM; International Centre for Tropical Agriculture: Cali-Palmira, Colombia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.Q.; Yu, B.L.; Yang, C.S.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Yao, S.J.; Qian, X.J.; Wang, C.X.; Wu, B.; Wu, J.P. An Extended Time-Series (2000–2023) of Global NPP-VIIRS-Like Nighttime Light Data [DB/OL]. Harvard Dataverse, 2020, V5. Available online: https://essd.copernicus.org/articles/13/889/2021/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- National Ice Center and National Snow and Ice Data Center. IMS Daily Northern Hemisphere Snow and Ice Analysis at 1 km Resolution, Version 1 [DB/OL]; Updated Daily; NSIDC: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoing, H.; Rodell, M. GLDAS Noah Land Surface Model L4 3 Hours 0.25 x 0.25 Degree V2.1 [DB/OL]; NASA Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC): Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, W.R.; Boehnert, J.; Bonan, G.B.; Langseth, M. Regridded Harmonized World Soil Database v1.2; ORNL Distributed Active Archive Center: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.P. Study on Soil Wind Erosion in China Based on Remote Sensing and GIS; Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Institute of Remote Sensing Applications): Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Su, K.; Yu, Q.; Yue, D.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Niu, T.; Sun, X. Simulation of a forest-grass ecological network in a typical desert oasis based on multiple scenes. Ecol. Model. 2019, 413, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, M.; Liu, S. A multi-criteria approach for ecological source identification in fragmented landscapes: Integrating MSPA, InVEST, and circuit theory. Ecol. Model. 2023, 475, 110203. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, H.M.; Syphard, A.D.; Franklin, J.; Swab, R.M.; Markovchick, L.; Flint, A.L.; Flint, L.E.; Zedler, P.H. Evaluation of assisted colonization strategies under global change for a rare, fire-dependent plant. Global Change Biol. 2011, 17, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.J.; Walty, J.R. Recovery Potential Assessment of Western Silvery Minnow (Hybognathus argyritis) in Canada; Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2014/038; Fisheries and Oceans Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- US Fish and Wildlife Service. Oregon Spotted Frog (Rana pretiosa) Recovery Plan; USFWS: Portland, OR, USA, 2014; pp. 1–46.

- Murcia, C. Edge effects in fragmented forests: Implications for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1995, 10, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, K.A.; Macdonald, S.E.; Burton, P.J.; Chen, J.; Brosofske, K.D.; Saunders, S.C.; Euskirchen, E.S.; Roberts, D.; Jaiteh, M.S.; Esseen, P.-A. Edge influence on forest structure and composition in fragmented landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.J.; Chang, J.S.; Du, Y.Y. The construction of county ecological network based on MCR and gravity model. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2023, 52, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yu, Q.; Pei, Y.R.; Wu, Y.; Niu, T.; Wang, Y. Characteristics of spatial ecological network in the Yellow River Basin of Northern China. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2022, 44, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Shi, P.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wan, Y.; Cheng, F.Y.; Wang, L. Ecological network optimization of Jiuquan City, Gansu, China based on complex network theory and circuit model. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 35, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; An, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, M. Ecological network construction of the heterogeneous agro-pastoral areas in the upper Yellow River basin. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 302, 107069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Ma, J.Z.; Wang, N.L. Quantitative Assessment of Wind Erosion Control by Vegetation in the Tengger Desert Using RWEQ Model. J. Arid Environ. 2019, 169, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, C.; Weixing, Z.; Ying, L. Algorithm for complex network diameter based on distance matrix. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2018, 29, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.H.; Yu, R.H. Review on Complex Network Theory Research. Comput. Syst. Appl. 2020, 29, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y.; Lin, X.Q.; Zhou, X.; Cui, W.J. Temporal and Spatial Evolution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Industrial Carbon Emissions in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 44, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q. A community partitioning algorithm for cyberspace. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Zhao, X.R.; Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiao, X.; Sui, Y. Pedogenesis of typical zonal soil drives belowground bacterial communities of arable land in the Northeast China Plain. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.B.; Guo, H.Q.; Yu, Q.; Mao, X.; Long, Q.; Yue, D. Ecospatial Network Optimization in Ordos Based on LMBA Strategy. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Zhu, Y.N.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.M.; He, G.H.; Wang, L.Z.; Chang, H.Y. Analysis of Urban Water and Energy Network Structure Based on Ecological Network Analysis Method. Water Resour. Power 2022, 40, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fryrear, D.W.; Saleh, A.; Bilbro, J.D.; Schomberg, H.M.; Stout, J.E.; Zobeck, T.M. Revised Wind Erosion Equation (RWEQ); Technical Bulletin 1; Wind Erosion and Water Conservation Research Unit, USDA-ARS, Southern Plains Area Cropping Systems Research Laboratory: Lubbock, TX, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.H.; Ma, T.H.; Wang, K.; Tan, M.; Qu, J.F. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern in Northern Peixian Based on MCR and SPCA. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2020, 36, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.P. Dynamic Evaluation of Windbreak and Sand Fixation Function in the Mu Us Sandy Land Based on RWEQ and Remote Sensing Data. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 2465–2478. [Google Scholar]

- Bachar, A.; Al-Ashhab, A.; Soares, M.I.M.; Sklarz, M.Y.; Angel, R.; Ungar, E.D.; Gillor, O. Soil microbial abundance and diversity along a low precipitation gradient. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.G.; Fan, J.Q.; Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhou, J.; Jia, Y.; Chi, W. Wind Erosion and Its Ecological Effects on Soil in the Northeastern Piedmont of the Yinshan Mountains. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 128, 107825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, D.; Pan, J. Incorporating Network Topology and Ecosystem Services into the Optimization of Ecological Network: A Case Study of the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z.; Yu, Q. Study on the relationship between ecological spatial network structure and regional carbon use efficiency: A case study of the Wuding River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Z.; Chang, C.; Du, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Li, Q. Regional Potential Wind Erosion Simulation Using Different Models in the Agro-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Guo, Z.; Chang, C.; Xiao, D.; Jiang, H. Quantitative estimation of farmland soil loss by wind-erosion using improved particle-size distribution comparison method (IPSDC). Aeolian Res. 2015, 19, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, B.; Xie, G.; Zhai, X.; Sun, H. Vegetation cover changes and sand-fixing service responses in the Beijing–Tianjin sandstorm source control project area. Environ. Dev. 2020, 34, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Xie, G.; Wang, Y.; Lei, G. Assessment of the benefit diffusion of windbreak and sand-fixation service in National Key Ecological Function Areas in China. Aeolian Res. 2021, 51, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data Source | Format | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China [40] | ZENODO database (https://zenodo.org/record/5816591#ZAWM3BVBy5c (accessed on 1 September 2025)) | tif | 1 km × 1 km | Annual |

| China regional 250 m normalized difference vegetation index dataset (2000–2023) [41] | National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center (https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.300328 (accessed on 1 September 2025)) | hdf | 1 km × 1 km | Month |

| The SRTMDEMUTM 90 m digital elevation data V4.1 [42] | Geospatial Data Cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/ (accessed on 1 September 2025)) | tif | 90 m × 90 m | / |

| An extended time-series (2000–2023) of global NPP-VIIRS-like nighttime light data [43] | Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YGIVCD (accessed on 1 September 2025)) | tif | 500 m × 500 m | Annual |

| Snow cover data [44] | IMS Daily Northern Hemisphere Snow and Ice Analysis (https://doi.org/10.7265/N52R3PMC (accessed on 1 September 2025)) | ASCII | 1 km × 1 km | 16 days |

| Wind speed data [45] | GLDAS-2.1, NASA LDAS (https://ldas.gsfc.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 1 September 2025)) | nc | 0.25° × 0.25° | 3 h per scene |

| Soil data [46] | World Soil Database (HWSD) (https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/harmonized-world-soil-database-v12/en/ (accessed on 1 September 2025)) | tif | 1 km × 1 km | / |

| Land-Use Type | Resistance |

|---|---|

| Forest, shrub, water area | 1 |

| Grassland | 2 |

| Farmland, wetland | 3 |

| Bare land | 4 |

| Ice and snow, impervious surface | 5 |

| Factor | Weight |

|---|---|

| land-use | 0.25 |

| Elevation | 0.14 |

| Slope | 0.13 |

| Nighttime light | 0.11 |

| Normalized difference vegetation index | 0.37 |

| Year | N | R | R2 | Adj.R2 | F | DW | β (Degree) | β (Betweenness Centrality) | β (PageRank) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 110 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 23.06 *** | 1.90 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.57 * |

| 2008 | 147 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 36.93 *** | 1.30 | 0.28 * | 0.20 * | 0.31 * |

| 2014 | 195 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 53.61 *** | 1.78 | 0.24 | 0.29 *** | 0.29 * |

| 2022 | 230 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 123.75 *** | 1.70 | 0.21 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.43 *** |

| Edge-Adding Strategy Type | Edge-Adding Strategy Method | Edge-Adding Proportion (%) | Average Degree | Average Betweenness Centrality (×10−4) | Average PageRank (×10−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Network (2022) | — | — | 5.63 | 679.00 | 5.30 |

| Degree Centrality | Low-Degree Edge Addition | 10 | 6.05 | 747.00 | 5.30 |

| Degree Centrality | Shortcut Edge Addition | 10 | 6.02 | 719.00 | 5.30 |

| Betweenness Centrality | Low-Betweenness Centrality Addition | 10 | 6.01 | 753.00 | 5.30 |

| Betweenness Centrality | Shortcut Edge Addition | 10 | 5.59 | 749.00 | 5.30 |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Low-Eigenvector Centrality Addition | 10 | 6.18 | 864.00 | 5.30 |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Shortcut Edge Addition | 10 | 6.15 | 759.00 | 5.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, Z.; Han, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, Q. Topological Structure Characteristics of Ecological Spatial Networks and Their Correlation with Sand Fixation Function. Land 2025, 14, 2388. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122388

Gu Z, Han Y, Li Q, Zhang Q, Yu Q. Topological Structure Characteristics of Ecological Spatial Networks and Their Correlation with Sand Fixation Function. Land. 2025; 14(12):2388. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122388

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Zijia, Yongtai Han, Qian Li, Qibin Zhang, and Qiang Yu. 2025. "Topological Structure Characteristics of Ecological Spatial Networks and Their Correlation with Sand Fixation Function" Land 14, no. 12: 2388. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122388

APA StyleGu, Z., Han, Y., Li, Q., Zhang, Q., & Yu, Q. (2025). Topological Structure Characteristics of Ecological Spatial Networks and Their Correlation with Sand Fixation Function. Land, 14(12), 2388. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122388