How Do Street Landscapes Influence Cycling Preferences? Revealing Nonlinear and Interaction Effects Using Interpretable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Xiamen Island

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Advances in Measuring Subjective Perception

2.2. Environmental Perception and Cognition

2.3. Nonlinear Mechanisms in Perceptual Response

3. Method

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Data

3.3. Research Methods

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Distribution of Cycling Preference Scores

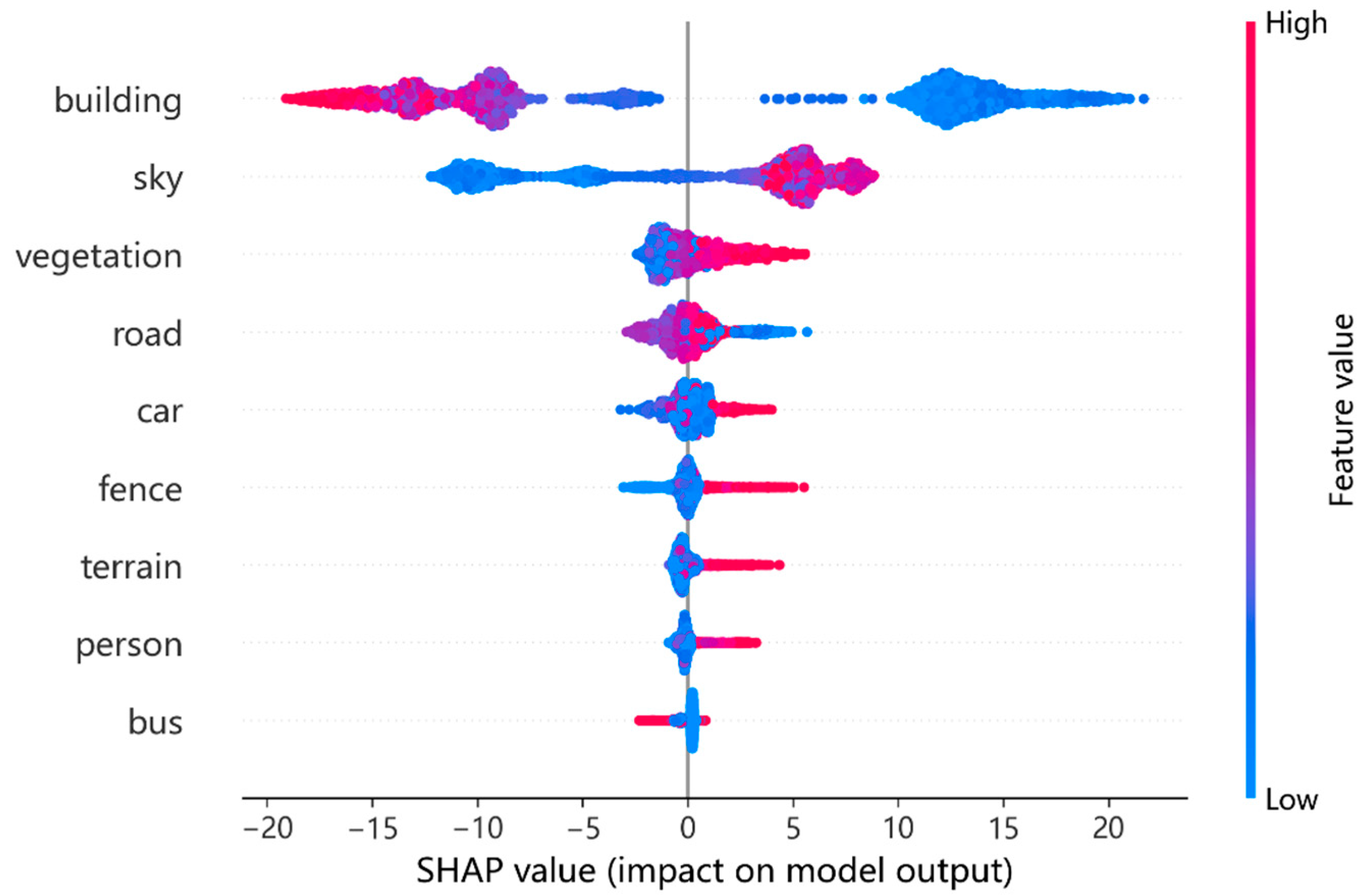

4.2. Relative Importance of Landscape Elements

4.3. Nonlinear Effects of Landscape Elements

4.4. Interaction Effects of Landscape Elements

5. Conclusions and Discussion

- (1)

- Spatial Distribution of Cycling Preference

- (2)

- Relative Importance of Streetscape Elements

- (3)

- Nonlinear Effects of Streetscape Elements

- (4)

- Interaction Effects of Streetscape Elements

- (5)

- Planning Implications and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crozet, Y. Cars and space consumption: Rethinking the regulation of urban mobility. In International Transport Forum Discussion Paper; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto Curiel, R.; González Ramírez, H.; Quiñones Domínguez, M.; Orjuela Mendoza, J.P. A paradox of traffic and extra cars in a city as a collective behaviour. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, J.; Kiggundu, A.T. The rise of the private car in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Assessing the policy options. IATSS Res. 2007, 31, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wei, D.; Zhao, P.; Yang, L.; Lu, Y. Revealing the spatiotemporal pattern of urban vibrancy at the urban agglomeration scale: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta, China. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 181, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Hanaoka, T. Cross-cutting scenarios and strategies for designing decarbonization pathways in the transport sector toward carbon neutrality. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulrazzaq, L.R.; Abdulkareem, M.N.; Yazid, M.R.M.; Borhan, M.N.; Mahdi, M.S. Traffic congestion: Shift from private car to public transportation. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 6, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R.; Sullivan, C. Green TODs: Marrying transit-oriented development and green urbanism. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2011, 18, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; de Barros, A.G.; Kattan, L.; Wirasinghe, S.C. Public transportation and sustainability: A review. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nello-Deakin, S.; Nikolaeva, A. The human infrastructure of a cycling city: Amsterdam through the eyes of international newcomers. Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.S.; Sharp, S.J.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Ogilvie, D.; Panter, J. Impacts of new cycle infrastructure on cycling levels in two French cities: An interrupted time series analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werschmöller, S.; Blitz, A.; Lanzendorf, M.; Arranz-López, A. The cycling boom in German cities. The role of grassroots movements in institutionalizing cycling. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2024, 18, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, M. Making a bicycle city: Infrastructure and cycling in Copenhagen since 1880. Urban Hist. 2019, 46, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; He, S.Y. Built environment effects on the integration of dockless bike-sharing and the metro. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 83, 102335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, K. Promoting bike-and-ride: The Dutch experience. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2007, 41, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissel, C.; Watkins, G. Impact on cycling behavior and weight loss of a national cycling skills program (AustCycle) in Australia 2010–2013. J. Transp. Health 2014, 1, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Jousilahti, P.; Borodulin, K.; Barengo, N.C.; Lakka, T.A.; Nissinen, A.; Tuomilehto, J. Occupational, commuting and leisure-time physical activity in relation to coronary heart disease among middle-aged Finnish men and women. Atherosclerosis 2007, 194, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Solomon, C.; Liu, S.; Colditz, G.A.; Speizer, F.E.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E. Physical activity and risk for cardiovascular events in diabetic women. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 134, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavill, N.; Kahlmeier, S.; Rutter, H.; Racioppi, F.; Oja, P. Economic Assessment of Transport Infrastructure and Policies. Methodological Guidance on the Economic Appraisal of Health Effects Related to Walking and Cycling; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Francke, A. Chapter Twelve-Cycling during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In Advances in Transport Policy and Planning; Heinen, E., Götschi, T., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Wei, Y.D.; Liu, M.; García, I. Green infrastructure inequality in the context of COVID-19: Taking parks and trails as examples. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 128027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. The impact of the “skeleton” and “skin” for the streetscape on the walking behavior in 3D vertical cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 227, 104543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Ji, X.; Sun, D.; Meng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lyu, M. Impact of streetscape built environment characteristics on human perceptions using street view imagery and deep learning: A case study of Changbai Island, Shenyang. Buildings 2025, 15, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xu, H.; He, H.; Wei, Q.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, T. A Spatial Analysis of Urban Streets under Deep Learning Based on Street View Imagery: Quantifying Perceptual and Elemental Perceptual Relationships. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, E.; Ye, Z. Identifying the nonlinear relationship between free-floating bike sharing usage and built environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ji, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Van Oort, N.; Jin, Y.; Hoogendoorn, S. A comparison in travel patterns and determinants of user demand between docked and dockless bike-sharing systems using multi-sourced data. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 139, 148–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärling, T.; Golledge, R.G. Environmental perception and cognition. In Advance in Environment, Behavior and Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; Volume 2, pp. 203–236. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, D.; Peng, H.; Cao, M.; Yao, Y. Is perceived safety a prerequisite for the relationship between green space availability, and the use and perceived comfort of green space? Wellbeing Space Soc. 2025, 8, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Oki, T.; Zhao, C.; Sekimoto, Y.; Shimizu, C. Evaluating the subjective perceptions of streetscapes using street-view images. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 247, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E.; Varelidis, G. Assessing Urban Public Space Quality: A Short Questionnaire Approach. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Using Google Street View to investigate the association between street greenery and physical activity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willberg, E.; Poom, A.; Helle, J.; Toivonen, T. Cyclists’ exposure to air pollution, noise, and greenery: A population-level spatial analysis approach. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2023, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Gong, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhuang, C.; Li, S. Measuring cyclists’ subjective perceptions of the street riding environment using K-means SMOTE-RF model and street view imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 128, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Van Wesemael, P. Conceptualizing cycling experience in urban design research: A systematic literature review. Appl. Mobilities 2021, 6, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. Polycentric urban form and non-work travel in Singapore: A focus on seniors. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 73, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Cao, J.; Yin, C.; Cheng, J. Examining the nonlinear relationships between park attributes and satisfaction with pocket parks in Chengdu. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 101, 128548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millstein, R.A.; Cain, K.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Geremia, C.; Frank, L.D.; Chapman, J.; Van Dyck, D.; Dipzinski, L.R.; Kerr, J. Development, scoring, and reliability of the Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes (MAPS). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Liang, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, P.; Bie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Guan, Q. A human-machine adversarial scoring framework for urban perception assessment using street-view images. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 33, 2363–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Wang, X.; Lyu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Heinen, E.; Sun, Z. Understanding cycling distance according to the prediction of the XGBoost and the interpretation of SHAP: A non-linear and interaction effect analysis. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 103, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.; Huxley, P. Mental illness in the community: The pathway to psychiatric care. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 1983, 6, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human–environment interactions in urban green spaces—A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Garcia, L.M.; Goodman, A.; Johnson, R.; Aldred, R.; Murugesan, M.; Brage, S.; Bhalla, K.; Woodcock, J. Estimating city-level travel patterns using street imagery: A case study of using Google Street View in Britain. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lee, J.H.; Yao, L.; Ostwald, M.J. Impact of built environments on human perception: A systematic review of physiological measures and machine learning. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Long, Y. Measuring physical disorder in urban street spaces: A large-scale analysis using street view images and deep learning. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2023, 113, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Grekousis, G.; Xiao, Y.; Ye, Y.; Lu, Y. Spatial disparity of individual and collective walking behaviors: A new theoretical framework. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 101, 103096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; Han, Z.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y. Using open source data to measure street walkability and bikeability in China: A case of four cities. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhou, B.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Fung, H.H.; Lin, H.; Ratti, C. Measuring human perceptions of a large-scale urban region using machine learning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, L.; Seo, S.H.; He, J.; Jung, T. Measuring perceived psychological stress in urban built environments using google street view and deep learning. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 891736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Liang, J.; Yang, M.; Li, Y. Visual preference analysis and planning responses based on street view images: A case study of Gulangyu Island, China. Land 2022, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H. Representing place locales using scene elements. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 71, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porzi, L.; Rota Bulò, S.; Lepri, B.; Ricci, E. Predicting and understanding urban perception with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Brisbane, Australia, 26–30 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; McRae, S. Subjectively safe cycling infrastructure: New insights for urban designs. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 101, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.L.; Fisher, B.; Grannis, M. Proximate physical cues to fear of crime. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1993, 26, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, F.S. The beginnings of Gestalt psychology in the United States. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 1977, 13, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H.; Sell, J.L.; Taylor, J.G. Landscape perception: Research, application and theory. Landsc. Plan. 1982, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cao, J.; Huting, J. Using three-factor theory to identify improvement priorities for express and local bus services: An application of regression with dummy variables in the Twin Cities. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 113, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Cao, X.; Wu, X.; Dong, Y. Examining pedestrian satisfaction in gated and open communities: An integration of gradient boosting decision trees and impact-asymmetry analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 185, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Hao, Z.; Yang, J.; Yin, J.; Huang, X. Prioritizing neighborhood attributes to enhance neighborhood satisfaction: An impact asymmetry analysis. Cities 2020, 105, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, X.; He, J.; Jung, T. Measuring residents’ perceptions of city streets to inform better street planning through deep learning and space syntax. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, L.; Zeng, P. Spatial heterogeneity of the built environment effect on the use of a bikeshare-metro commute in a metropolitan area: A case study of shenzhen. Trop. Geogr. 2023, 43, 872–884. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Liang, Y.; Yang, L. Exploring the relationship between bike-sharing ridership and built environment characteristics: A case study based on GAMM in Boston. World Reg. Stud. 2023, 32, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Lo, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q. Nonlinear and synergistic effects of TOD on urban vibrancy: Applying local explanations for gradient boosting decision tree. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Hu, Y.; Liang, C.; Wan, Q.; Dai, Q.; Yang, H. Understanding nonlinear and synergistic effects of the built environment on urban vibrancy in metro station areas. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 70, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.S.; Nichol, J.; Ng, E. A study of the “wall effect” caused by proliferation of high-rise buildings using GIS techniques. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 102, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Schröder, T.; Bekkering, J. Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability: A critical review. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 114–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Langenheim, N.; Yang, T.; Dia, H.; Woodcock, I.; Paay, J. Do Trees Really Make a Difference to Our Perceptions of Streets? An Immersive Virtual Environment E-Participation Streetscape Study. Land 2025, 14, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guan, X.; Lu, Y. Deciphering the effect of user-generated content on park visitation: A comparative study of nine Chinese cities in the Pearl River Delta. Land Use Policy 2024, 144, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Cycling preference score | 48.23 | 18.34 | 16.53 | 93.85 |

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Road view index | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.41 |

| Building view index | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0 | 0.57 |

| Fence view index | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.15 |

| Vegetation view index | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0 | 0.85 |

| Terrain view index | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.05 |

| Sky view index | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0 | 0.60 |

| Person view index | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 |

| Car view index | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.10 |

| Bus view index | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, P.; Huang, J.; Fang, L.; Luo, C.; Zhang, E.; Wang, G. How Do Street Landscapes Influence Cycling Preferences? Revealing Nonlinear and Interaction Effects Using Interpretable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Xiamen Island. Land 2025, 14, 2253. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112253

Hu P, Huang J, Fang L, Luo C, Zhang E, Wang G. How Do Street Landscapes Influence Cycling Preferences? Revealing Nonlinear and Interaction Effects Using Interpretable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Xiamen Island. Land. 2025; 14(11):2253. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112253

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Pengliang, Jingnan Huang, Libo Fang, Chao Luo, Ershen Zhang, and Guoen Wang. 2025. "How Do Street Landscapes Influence Cycling Preferences? Revealing Nonlinear and Interaction Effects Using Interpretable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Xiamen Island" Land 14, no. 11: 2253. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112253

APA StyleHu, P., Huang, J., Fang, L., Luo, C., Zhang, E., & Wang, G. (2025). How Do Street Landscapes Influence Cycling Preferences? Revealing Nonlinear and Interaction Effects Using Interpretable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Xiamen Island. Land, 14(11), 2253. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112253