Cultural Memories and Sense of Place in Historic Urban Landscapes: The Case of Masrah Al Salam, the Demolished Theatre Context in Alexandria, Egypt

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

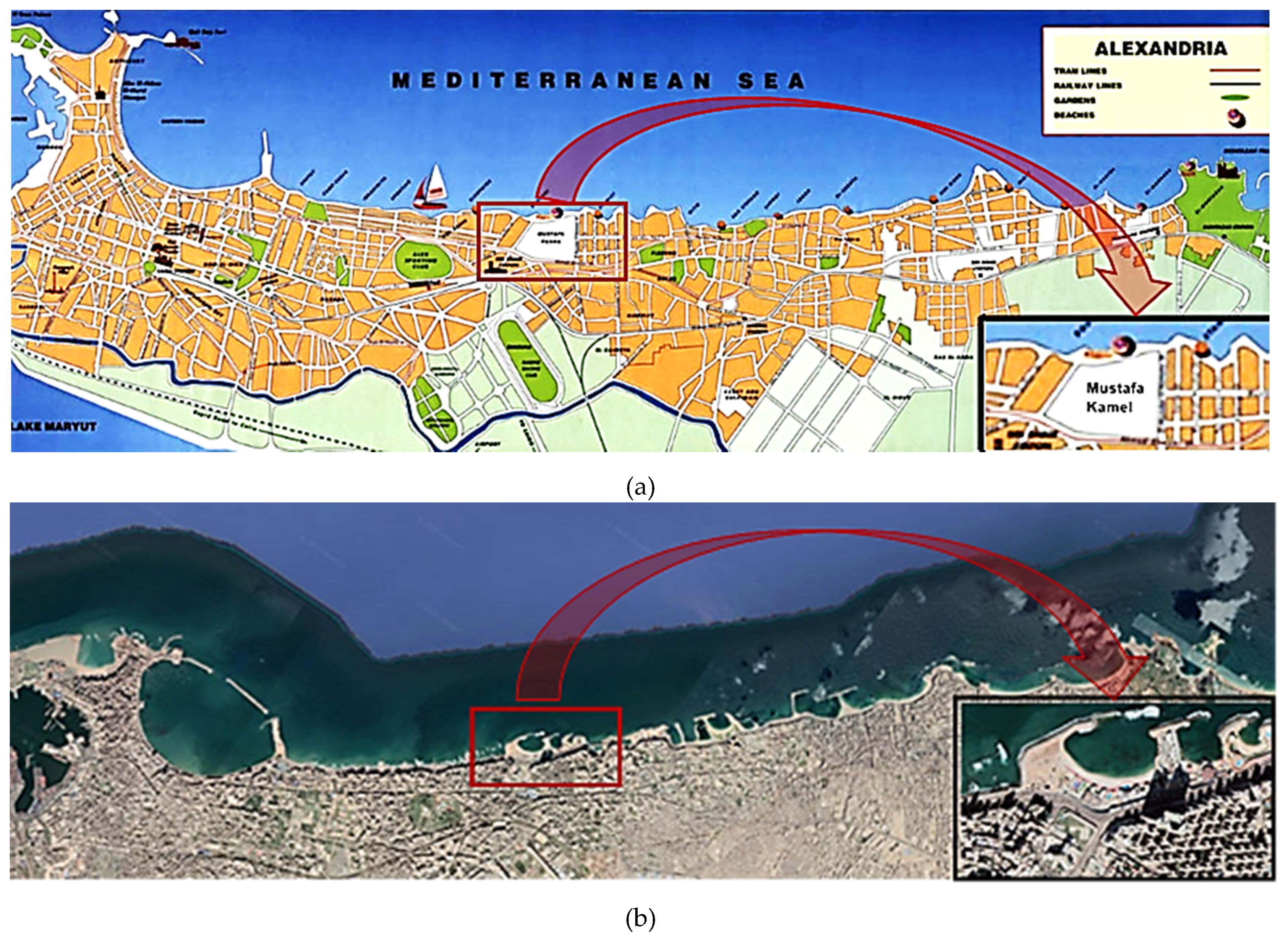

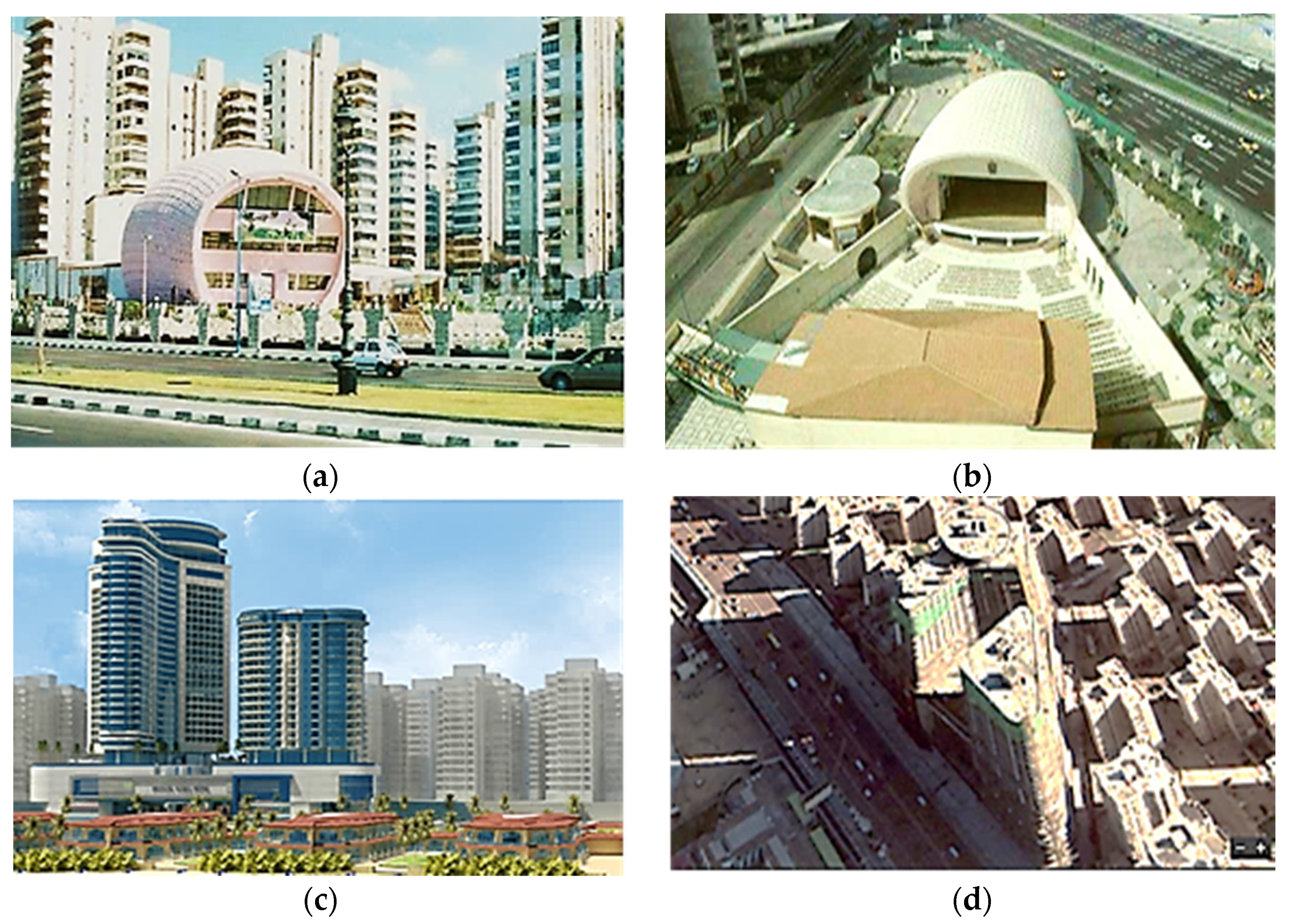

2.1. Study Setting

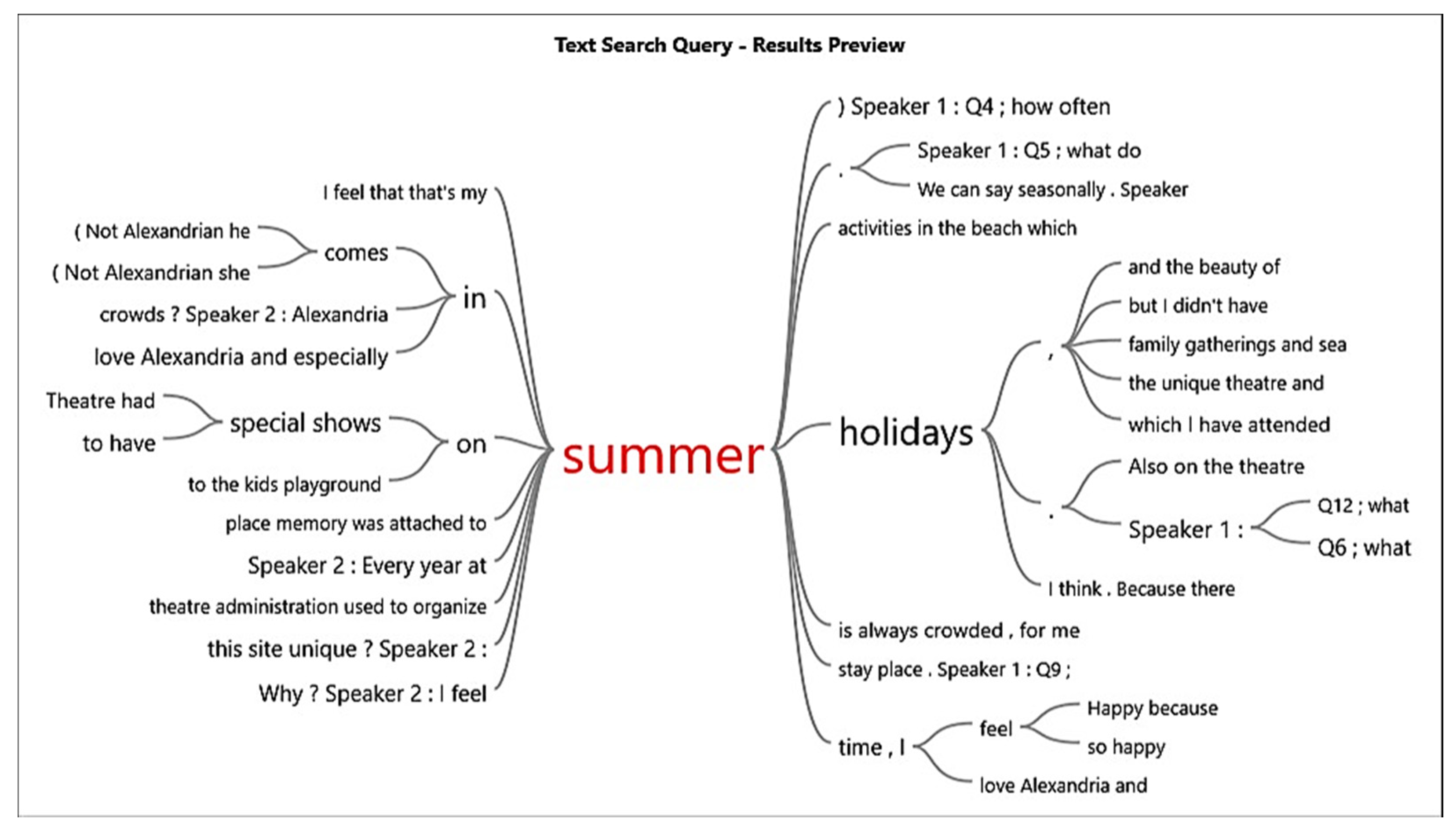

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cultural Memories Stored in the Place (Formation of Events and Recording Similarities)

‘Removing the theatre is an unforgivable crime! I entered this theatre once when I was a child to attend a puppet show. However, every time I passed by the theatre I used to smile just because I remember that great time and how I was so happy that day. Also, because I used to feel that the kids who were playing in the theatre’s front garden are enjoying the same feelings that I enjoyed when I was young, I think what happened is a destruction for the site’s memory and symbolism’—Heba Moo’nis (sample of analysed Facebook comments)

‘There is no specific story that was connected to the theatre except its old repetition of exceptional summer plays that people used to attend long times ago. While, now there is the debate between Alexandrians around removing the theatre and how people were angry about that. This affects my experience by feeling angry every time I pass and remember how we lost the theatre despite the peoples refusing and I feel sorry for that’—23-year-old female interviewee (sample of analysed answers).

3.2. Place Attachment (Practice, Cognitive, and Affective)

‘I’m so bonded to this place, first because a live here. Second because I used to come and play in the theatre’s removed playground so it was a gathering place for me and my friends. Also it’s like a guide for me, it’s in the middle of Alexandria’s promenade, so even if you are not coming specifically for the site you will pass by it any way it was a landmark’—43-year-old female interviewee (sample of analysed answers).

3.3. Site Identity (Continuity and Distinctiveness)

‘I’m already uncomfortable about losing the eye contact with the sea view, due to the new changes and the traffic bridge. Because having a sea view was part of my experience here and that leaves me feeling that this is not the same place that I used to come to before and enjoy’—27-year-old female interviewee (sample of analysed answers)

3.4. Sense of Place (Relationship to the Place and Community Attachment)

‘I’m very sad because of losing the theatre. Also, uncomfortable about the new buildings preventing the sea view and causing a big traffic jam. The area has lost its old spirit and it is totally changed now. I would prefer that the theatre has been kept with off course conservation and renovation, and adding the shopping and dining services this would have been a very nice entertaining complex’—53-year-old male interviewee (sample of analysed answers)

‘The area became so crowded, I don’t like crowds specially the traffic ones, it’s so annoying and time consuming. Also crowds make you feel that the place is small even if it’s big and that is uncomfortable and pushes people to react more angry and tensioned. Now you can’t enjoy having a walk viewing the open sea view, you have to go to a restaurant or a café to enjoy that, you have to be rich!’—50-year-old male interviewee (sample of analysed answers)

‘I feel sad and ashamed for the idea of existing and living during this period of time witnessing this tragic deterioration and after all I couldn’t stop it or change it’.—Kareem Bahgat Al-Maghrabi (sample of analysed Facebook comments)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval

References

- Carrà, N. Identity and Urban Values for Sustainable Design. Adv. Eng. Forum 2014, 11, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leila Mahmoudi, F.; Marzieh, S.; Leila, S. Contextualizing Palimpsest Of Collective Memory In An Urban Heritage Site: Case Study of Chahar Bagh, Shiraz-Iran. Archnet IJAR 2015, 9, 218–231. [Google Scholar]

- Molavi, M.; Rafizadeh Malekshah, E.; Rafizadeh Malekshah, E. Is collective memory impressed by urban elements? Manag. Res. Pract. 2017, 9, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; Bandarin, F., van Oers, R., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ginzarly, M.; Pereira Roders, A.; Teller, J. Mapping historic urban landscape values through social media. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Landscape and Memory: Cultural Landscapes, Intangible Values and Some Thoughts on Asia. In Proceedings of the 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: Finding the Spirit of Place—Between the Tangible and the Intangible, Quebec, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lib, T.M. Memory the Macquarie Library. Available online: https://www.macquariedictionary.com.au/ (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ardakani, M.K.; Oloonabadi, S.S.A. Collective memory as an efficient agent in sustainable urban conservation. Procedia Eng. 2011, 21, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darian-Smith, K.; Hamilton, P. Memory and History in Twentieth-Century Australia; Darian-Smith, K., Hamilton, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory; Coser, L.A., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, P. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire. In Memory and Counter-Memory; No. 26 Special issue; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, G. Collective Memory; AGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Hakimian, P. Collective memory and urban regeneration in urban spaces: Reproducing memories in Baharestan Square, city of Tehran, Iran. City Cult. Soc. 2019, 18, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hałas, E. Issues of Social Memory and their Challenges in the Global Age. Time Soc. 2008, 17, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AlGhanim, K.; Gardner, A.; El-Menshawy, S. The relation between spaces and cultural change: Supermalls and cultural change in qatari society. Sci. Cult. 2017, 3, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N. Preserving Urban Landscapes as Public History: The Chinese Context. Public Hist. 2010, 32, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbakhsh, H.; Koumleh, M.H.; Alambaz, F.S. Methods and Techniques in Using Collective Memory in Urban Design: Achieving Social Sustainability in Urban Environments. Cumhur. Univ. Fac. Sci. J. (CSJ) 2015, 36, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.V. Theory of attachment and place attachment. In Psychological Theories for Environmental Issues; Bonnes, M., Lee, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 137–170. [Google Scholar]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Mowen, A.J.; Tarrant, M. Linking place preferences with place meaning: An examination of the relationship between place motivation and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. Place Attachment; Altman, I., Setha, M.L., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ujang, N.; Zakariya, K. Place Attachment and the Value of Place in the Life of the Users. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 168, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskiewicz, M. Place attachment, place identity and aesthetic appraisal of urban landscape. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 46, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montgomery, J. Making a city: Urbanity, vitality and urban design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N. Place Attachment and Continuity of Urban Place Identity. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bevan, R. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, 2nd ed.; Bevan, R., Ed.; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.; Stedman, R. Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E.C. Place and Placelessness. Research in Planning and Design/A Revision of the Author’s Thesis; University of Toronto: London, ON, Canada, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, F. The Sense of Place; CBI Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hummon, D.M. Community Attachment: Local Sentiment and Sense of Place. In Place Attachment; Iaasm, L., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer, B.; Krannich, R.; Blahna, D. Attachments to Special Places on Public Lands: An Analysis of Activities, Reason for Attachments, and Community Connections. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2000, 13, 421–441. [Google Scholar]

- Shamai, S.; Ilatov, Z. Measuring sense of place: Methodological aspects. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, N.M.N.; Saruwono, M.; Said, S.Y.; Hariri, W.A.H.W. A Sense of Place within the Landscape in Cultural Settings. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, W.S.-W. Memories and urban places. Analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action. City 2000, 4, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Whoqol: Measuring Quality of Life. In World Health Organization Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Golledge, R.G. Spatial Behavior: A Geographic Perspective; Stimson, R.J., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- DeMiglio, L.; Williams, A. A Sense of Place, A Sense of Well-being. In Sense of Place, Health, and Quality of Life; John Eyles, A.W., Ed.; Ashgate: Burlington, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, S.; Nishimura, Y.; Kubota, A. Memory Association in Place Making: A review. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 85, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Cultural Memory For Psychosocial Well-Being In Historic Urban Landscapes An Existing But A Neglected Dimension. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Interdiscip. Stud. (IJSSIS) 2019, 4, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Cultural Memories for Better Place Experience: The Case of Orabi Square in Alexandria, Egypt. Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexandria Portal Egypt 2019. Available online: http://www.alexandria.gov.eg/Alex/english/index.aspx (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- JustMaps. Maps of Alexanderia Valencia (Spain): Internet Studios. 2005. Available online: http://www.justmaps.org/maps/images/egypt/alexandria-map2.jpg (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Morgan, A. Six Touristic Buildings were Demolished from Alexandria by the End of 2016 (Arabic Source) Sout Al Umma: Sout Al Umma Journal. 2016. Available online: https://www.soutalomma.com/465080 (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Deyaa, N. Another Legacy Wasted: Alexandria’s Al-Salam Theatre is Demolished. Daily News Egypt. 2016. Available online: https://dailynewsegypt.com/2016/06/26/another-legacy-wasted-alexandrias-al-salam-theatre-demolished/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Zeinobia. Farewell El-Salam Theatre of Alexandria “Updated” 2016. Available online: https://egyptianchronicles.blogspot.com/2016/06/june-13-2016-at-1225am.html (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- ECO Group. Mostafa Kamel Hotel—Cornish Road—Alexandria Egypt 2020. Available online: http://ecoalx.com/project/mostafa-kamel-hotel-cornish-road-alexandria/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Morse, J.M. Designing Funded Qualitative Research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 220–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, J. Connecting with the past through social media: The ‘Beautiful buildings and cool places Perth has lost’ Facebook group. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hoeven, A. Historic urban landscapes on social media: The contributions of online narrative practices to urban heritage conservation. City Cult. Soc. 2019, 17, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Desha, C. Engaging in design activism and communicating cultural significance through contemporary heritage storytelling: A case study in Brisbane, Australia. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 6, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olsen, W. Triangulation in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods Can Really Be Mixed. In Developments in Sociology; Holborn, M., Ed.; Causeway Press: Ormiskirk, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mapio Net. Available online: https://cdn-0.mapio.net/images-p/23459695.jpg (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Ezzeldin, A. “You Won’t Believe Who is the Real Sound behind Boa Loz” Translated from Arabic Title Egypt: La2tat.com. Available online: https://www.l2tat.com/%D8%A3%D8%AE%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A%D9%86/%D9%84%D9%86-%D9%8A%D8%B9%D8%B1%D9%81%D9%87-%D8%B3%D9%88%D9%89-%D8%AC%D9%8A%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%84%D9%86-%D8%AA%D8%B5%D8%AF%D9%82-%D9%85%D9%86/.2018 (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Kansteiner, W. Finding Meaning in Memory: A Methodological Critique of Collective Memory Studies. Hist. Theory 2002, 41, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Perkins, D. Distruptions in Place Attachment. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B.B.; Altman, I.; Werner, C.M. Place Attachment. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, J.E. What is Sense of Place? In Proceedings of the 12th Headwaters Conference, Gunnison, CO, USA, 2–4 November 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eyles, J. Senses of Place; Silverbrook Press: Warrington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lucy, W. If Planning Includes Too Much, Maybe It Should Include More. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1994, 60, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, I.; Eliasson, I. Relationships between Personal and Collective Place Identity and Well-Being in Mountain Communities. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Age | Women | Men | Total (No.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19–34 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 35–49 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| 50–65 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Cultural Memories and Sense of Place in Historic Urban Landscapes: The Case of Masrah Al Salam, the Demolished Theatre Context in Alexandria, Egypt. Land 2020, 9, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9080264

Hussein F, Stephens J, Tiwari R. Cultural Memories and Sense of Place in Historic Urban Landscapes: The Case of Masrah Al Salam, the Demolished Theatre Context in Alexandria, Egypt. Land. 2020; 9(8):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9080264

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussein, Fatmaelzahraa, John Stephens, and Reena Tiwari. 2020. "Cultural Memories and Sense of Place in Historic Urban Landscapes: The Case of Masrah Al Salam, the Demolished Theatre Context in Alexandria, Egypt" Land 9, no. 8: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9080264