Using a Gender-Responsive Land Rights Framework to Assess Youth Land Rights in Rural Liberia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Formative Qualitative Research

2.3. Baseline Survey

2.4. Women’s Land Rights Conceptual Framework

- Statutory and customary land-related laws, policies, regulations, conventions, and agreements that embody the rights determined and enforced by governments;

- Formal and informal institutions and actors who influence, decide, manage, or enforce land-related rights;

- Social norms that shape attitudes and beliefs on who should have land, for what purpose and through which means; and

- Individuals and communities whose land-related rights are protected, strengthened, limited or negated by the system.

3. Presenting Findings Using the Gender-Responsive Land Rights Framework

3.1. Is the Extent of the Bundle of Rights Clearly Defined and Enforced? (Completeness)

3.1.1. Are the Rights for Female and Male Youth Clearly Defined under the LRA and Related Laws That Govern Land Rights?

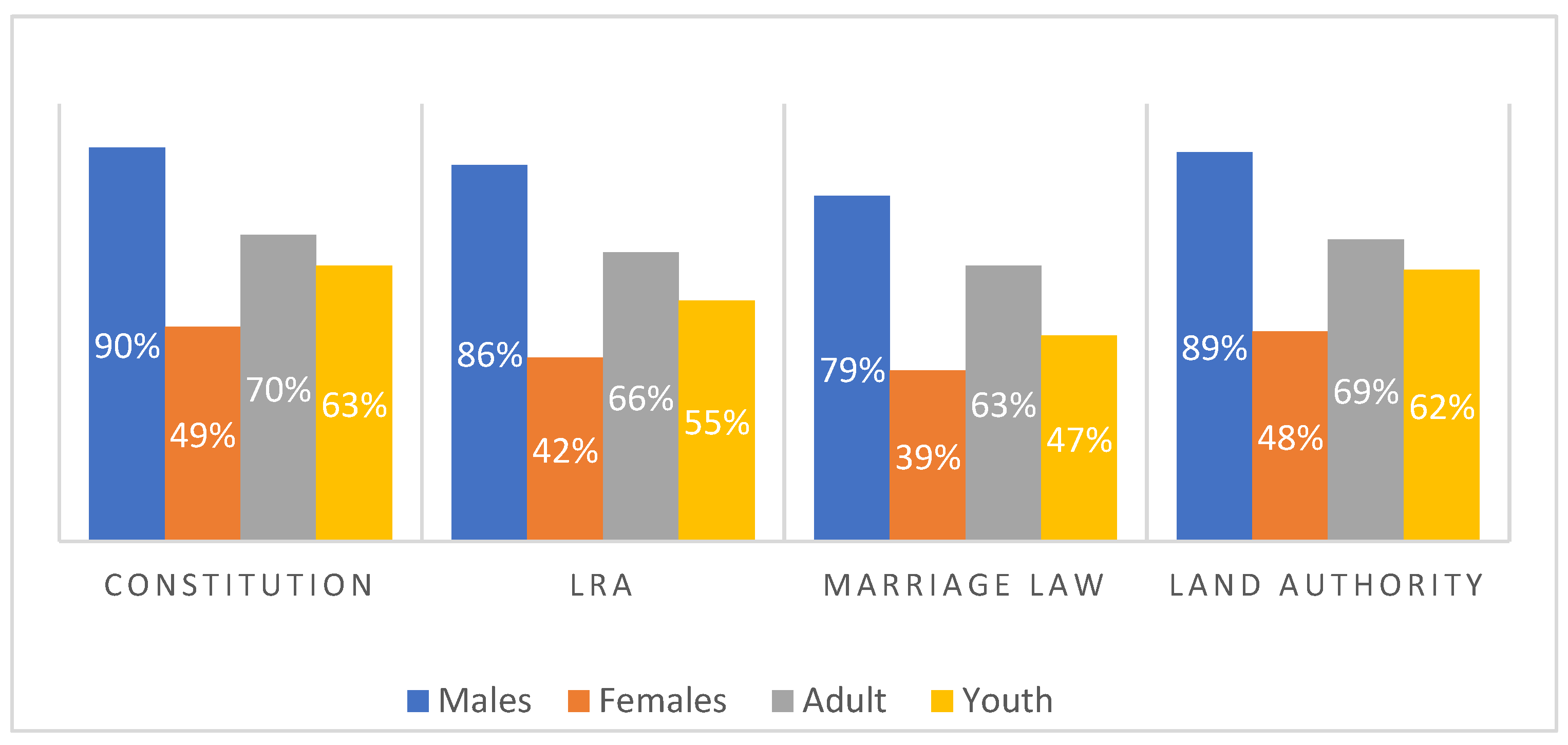

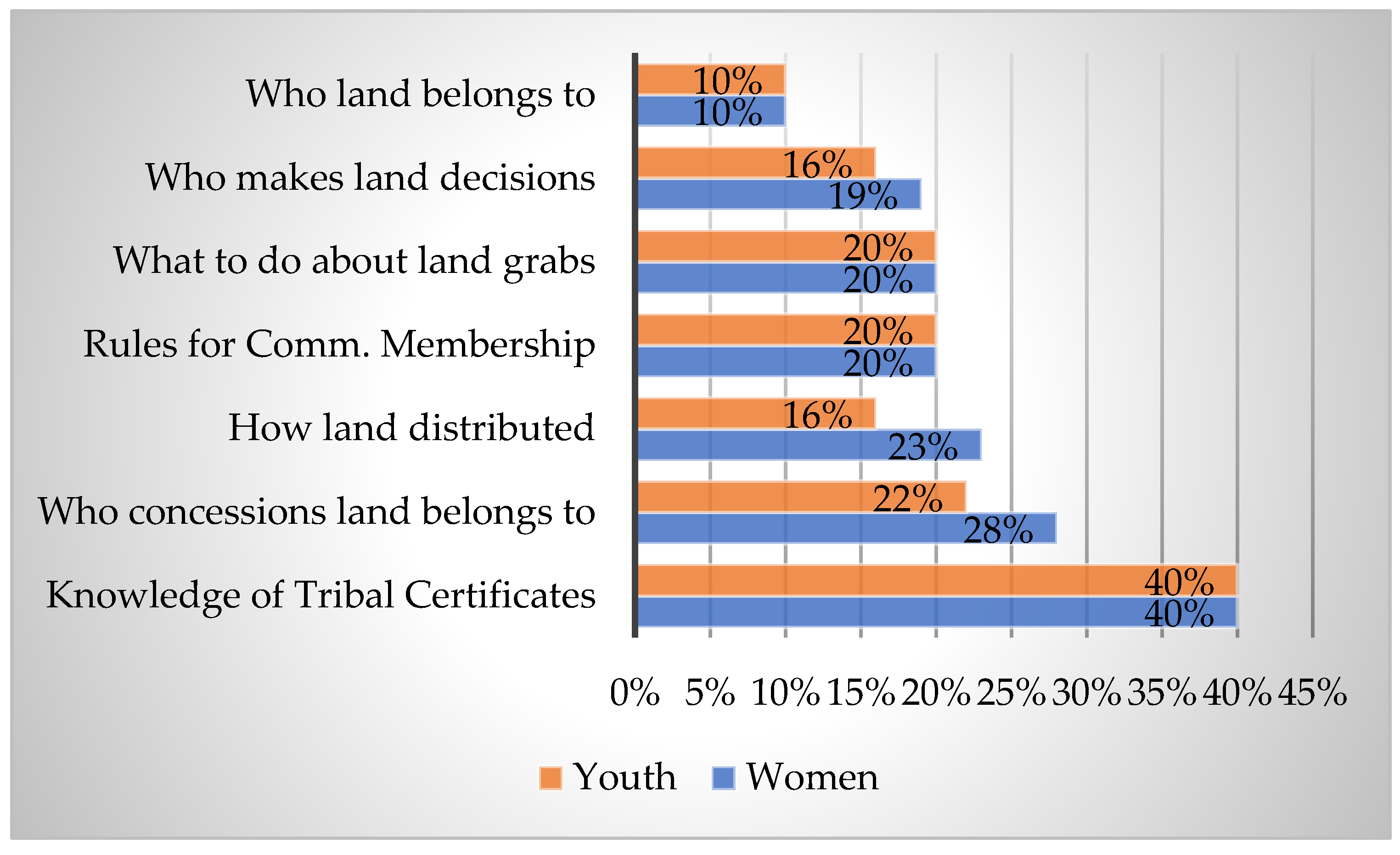

3.1.2. Do Youth Have Knowledge of Their Bundle of Rights (i.e., Have They Been Clearly Defined for the Youth)? Are Youth Knowledgeable about Who Can Gain New Rights to Land and under What Circumstances? Is This the Case for All Youth?

- Males are the heads of households.

- Elder males and landlords (male) have the most rights and privileges to land.

- Land matters are for males, not females.

- Elder males are the arbiters of land access and governance and need to be approached in the traditional way for land.

- Youth must approach elders for land.

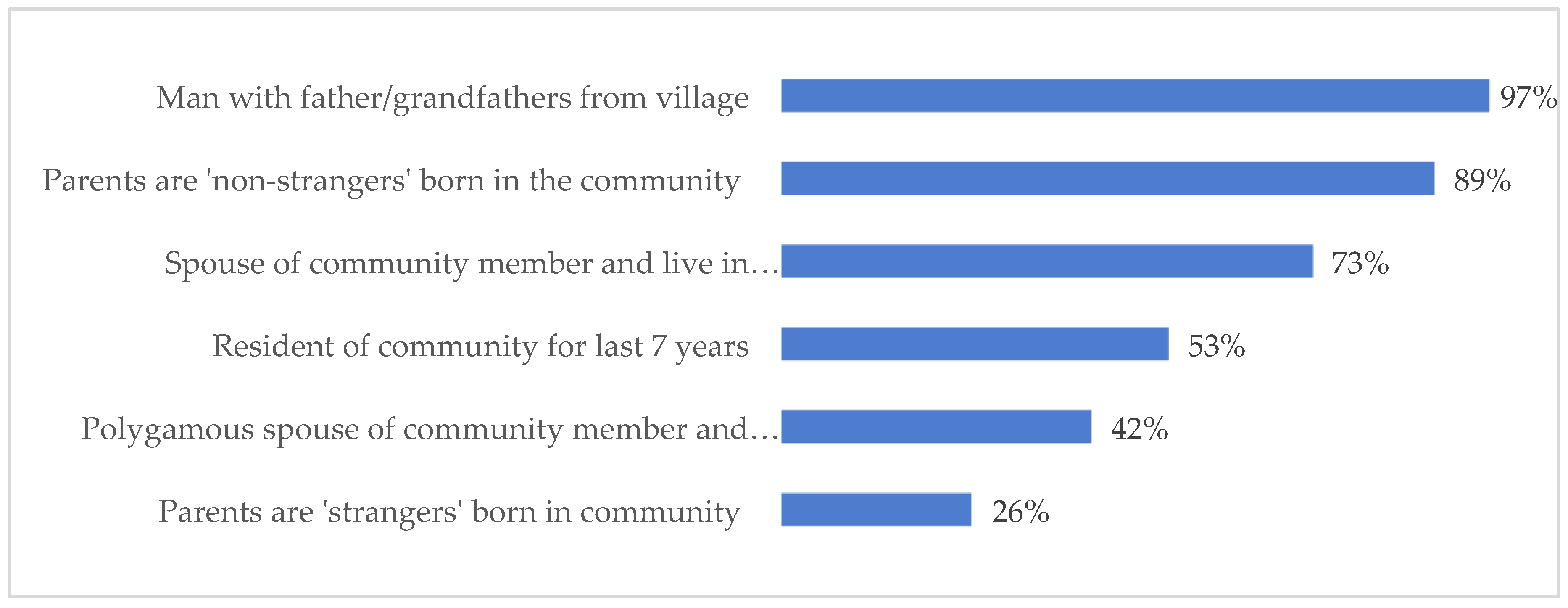

- Youth can only access land within the community if he is a community member (i.e., his father is from the community).

- “Strangers” (i.e., parents were not born in the community) have more restricted access to land.

3.1.3. Are Youth Able to Enjoy the Full Extent of Their Bundle of Rights? Are Youth Able to Gain New Rights to Land If They Meet the Criteria for Eligibility? Is This the Case of All Youth?

3.1.4. Are Women Able to Enjoy the Full Extent of Their Bundle of Rights? Do Women Have Knowledge about Who Can Gain New Rights to Land and under What Circumstances? Is This the Case for All Women?

3.2. Are the Bundle of Rights Clearly Enforced in the Face of Contestation (Robustness)?

3.2.1. Does the LRA Clearly Define Enforcement of Rights in the Face of Contestation

3.2.2. Do Youth Have Knowledge of Their Rights in the Face of Contestation or Changed Circumstances? Is This the Case for All Youth?

3.2.3. Are Youth Able to Enforce Their Rights in the Face of Contestation or Changed Circumstances? Is This the Case for All Youth?

3.2.4. Are Women Able to Enforce Their Rights in the Face of Contestation or Changed Circumstances? Is This the Case for All Women?

3.3. Does the Land Rights System Give All the Ability to Participate in Decisions about the Land (Inclusive & Gender Equitable)?

3.3.1. Does the LRA Clearly Define Land Rights/Land Governance as Inclusive and Gender-Equitable?

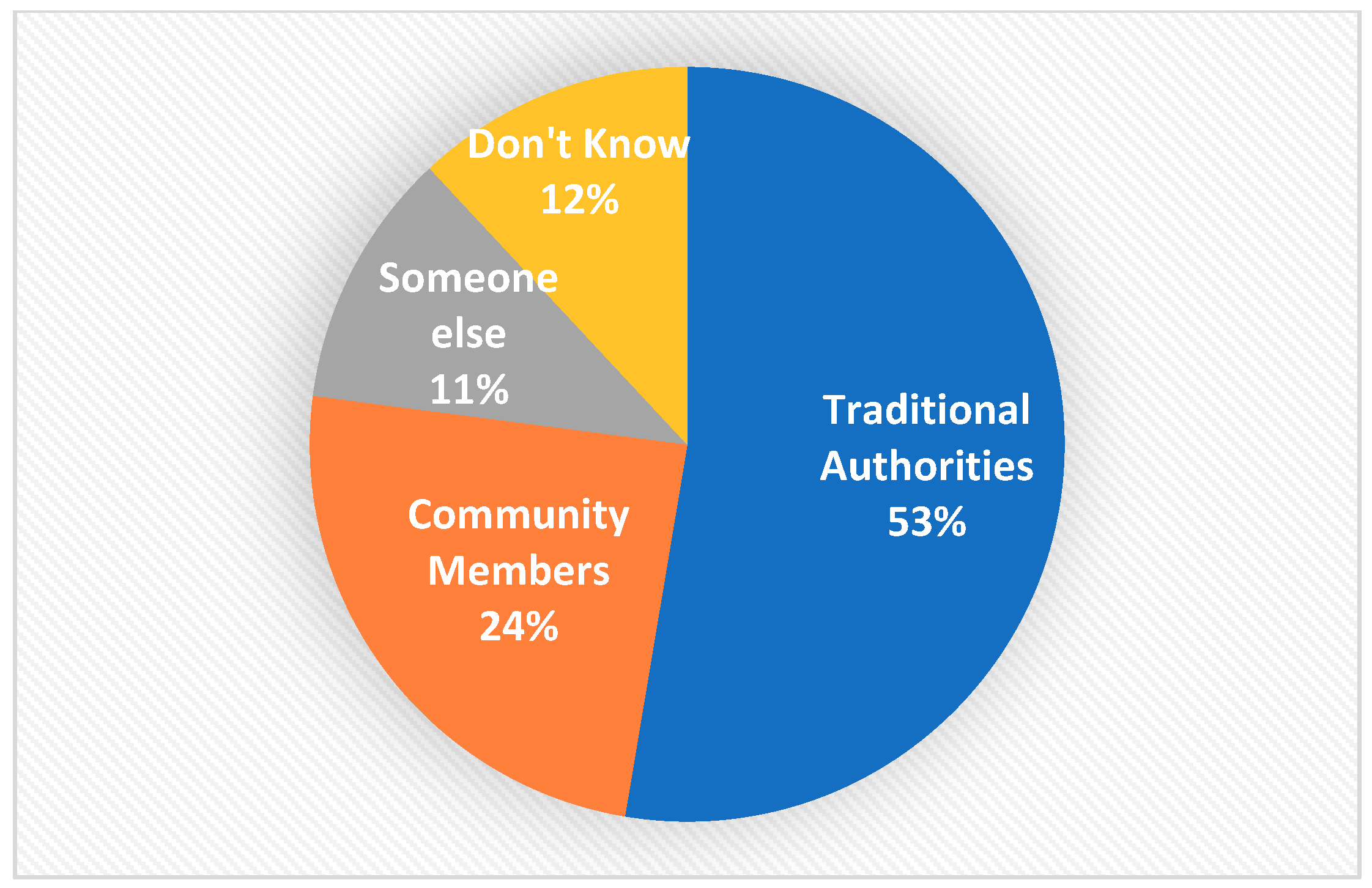

3.3.2. Do Youth Understand Their Rights as They Relate to Decision-Making on Land Governance?

3.3.3. Are Youth Able to Participate in Land Decisions at the Household and Community Level? Is This the Case of All Youth?

3.3.4. Are Women Able to Participate in Land Decisions at the Household and Community Level? Is This the Case of All Women?

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Land Tenure Security on Youth Livelihoods

4.2. Recommendation for Policy and Programming

- Land rights CSOs should co-develop and co-implement cross-sectoral youth livelihood and empowerment programs that seek to address not only youth land access and ownership challenges but also limited youth access to inputs, markets, poor transportation, low crop prices, and weather related challenges that discourage Liberian youth from pursuing a career in agriculture. The cross-sectoral youth and land interventions should also include nationwide radio and television programs showcasing successful youth farmers who can act as role models and drive home the idea of “agriculture as a business” and viable employment opportunity for Liberian youth.

- Supporting land rights education and awareness-raising to enable rural Liberian youth to better understand and defend their land rights as provided for in local customary and national statutory land rights frameworks. Community sensitization on the importance of youth land rights for sustainable rural youth livelihoods would be beneficial. The sensitization should especially target traditional gatekeepers such as customary leaders, landlords, elders, and local government officials, including town and quarter chiefs.

- Developing simplified language to popularize the provision of the Land Rights Act through online platforms such as WhatsApp and Facebook to increase the number of youth who are aware of the Land Rights Act and its provisions.

- Providing targeted and continuous youth land rights training at all levels of the traditional power structures and formal land administration systems to gradually break the deeply entrenched and oftentimes discriminatory land allocation and ownership systems that favor adult men and young men.

- Providing simplified land rights training and awareness raising Training of Trainers (ToTs) and community-based programs to grassroots-oriented youth associations, women’s groups, and Community Based Organizations working with young farmers with particular attention to local organizations working with young women.

- Addressing ambiguities and questions around “who is a community member” by educating community elders, youth, and their representatives organizations about the community membership qualification provisions under the Land Rights Act to ensure that the community and youth’s understanding of community membership evolves toward a more inclusive membership criteria that protects the land rights of youth “strangers” and their children, and spouses and wives in de-facto unions and polygamous marriages.

- Promoting adult-youth dialogue on land matters in order to improve opportunities for youth to access land. This could be done by strengthening existing community platforms for youth-adult dialogue where they already exist (e.g., Yeala in Lofa County), as well as developing and supporting new youth-adult land rights dialogue forums where these do not exist. These dialogue forums could enhance youth engagement in broader community land governance systems and boost opportunities for youth access to land.

- Promoting youth-adult dialogue on land matters by organizing community-, county-, and national-level multi-stakeholder youth land rights workshops bringing together youth leaders, customary authorities, government officials, private companies, and development partners to educate stakeholders about the importance of youth land rights, youth related provisions in the LRA and innovative approaches to foster youth land ownership, and effective engagement of young men and young women in land related decision-making processes.

- Developing youth-oriented land rights advocacy initiatives based on thorough youth segmentation and considerations for most disadvantaged groups of youth including strangers, unmarried youth, females, and those in de-facto unions and polygamous marriages.

- Developing and promoting youth sensitive land rental market policies to better protect the land rights of youth from unscrupulous landlords and traditional leaders especially in Bong County where there is an informal, unregulated land rental market.

- Encouraging the Government of Liberia to develop community-level social security schemes that can incentivize and quicken intergenerational land transfers.

- Land rights CSOs should work with customary authorities and government officials to prepare a database of vacant or underutilized land that can be reallocated to prospective youth farmers especially those residing in and around major urban centers like Gbarnga and Voinjama. The database can be shared with youth associations to help identify landless youth who are interested in farming and connecting the youth to landowners or allocation authorities.

- Training youth leaders in land dispute resolution mechanisms including Alternative Land Dispute Resolution to build the capacity of youth farmers to recognize and defend their land rights when they are infringed upon by customary and statutory authorities. Land rights CSOs should work with the Liberia Land Authority to ensure the development of regulations that stipulate quotas for youth engagement in customary land dispute resolution mechanisms including Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) approaches. The regulations should define clear procedures for the protection of male and female youth land rights.

- Engage youth and their representative organizations in community boundary harmonization, mapping and surveying processes to ensure that youth have a good understanding of the historical evolution of land issues in Liberian communities where boundary disputes and intergenerational tensions over land are common.

- Civil society organizations should work with customary authorities and community leaders across the country to ensure the participation of male and female youth in the collective community development of bylaws, land-use plans and Community Land Development and Management Committees (CLDMCs). The community bylaws should indicate collectively agreed quotas for male and female youth participation in land-use planning processes and representation in CLDMCs.

- Building the capacity of grassroots-oriented rural youth organizations by educating them about land rights and linking them up with customary and statutory authorities that mediate rural youth access to land and opportunities for land-based livelihoods.

- In Bong and Lofa counties, communities where there is increasing land scarcity especially close to major urban centers, identifying and promoting profitable small-scale, intensive farming activities that target landless unemployed, and connecting the youth with land owners and land allocation authorities to promote group leasing, contract farming, and access to urban markets to improve youth access to land and quick income generating opportunities.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Namubiru-Mwaura, E.; Knox, A.; Hughes, A. Liberia Land Policy and Institutional Support (LPIS) Project. Customary Land Tenure in Liberia: Findings and Implications Drawn from 11 Case Studies. Report Prepared for USAID, under the Auspices of the Land Commission of the Republic of Liberia and coordinated by Landesa and Tetra Tech ARD. Available online: https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/USAID_Land_Tenure_Liberia_LPIS_Synthesis_Report.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- United States Agency for International Development Office of Food for Peace (USAIDFFP). Country-Specific Information: Liberia Fiscal Year 2016 Development Food Assistance Program: Liberia Community Development Project. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/2016%20Final%20Liberia%20CSI.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- CIA The World Factbook: Liberia. Central Intelligence Agency, Central Intelligence Agency, 1 Feb. 2018, CIA World Factbook. 2018. Available online: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/li.html (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- UNDESA World Population Prospects, Revision. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/tr (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- TRC Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Liberia (TRC) Volume I: Findings and Determinations. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/3B6FC3916E4E18C6492575EF00259DB6-Full_Report_1.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Bruce A Strategy for Further Reform of Liberia’s Law on Land. Land Governance Support Activity USAID/Tetratech. Available online: https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/USAID_Land_Tenure_LGSA_Report_Reform_Strategy_Liberia_Law_Land.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Dodd, M.-L.; Duncan, J.; Uvuza, J.; Nagbe, I.; Neal, V.D.; Cummings, L. Women’s Land Rights in Liberia in Law, Practice, and Future Reforms: LGSA Women’s Land Rights Study. Technical report, USAID. Available online: https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/USAID_Land_Tenure_LGSA_WLR_Study_Mar-16-2018.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- De Wit, P.; Stevens, C. 100 Years of Community Land Rights in Liberia: Lessons Learned for the Future. [Presentation]. Paper Presented at the World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. Washington, D.C. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/pt/896191468762635261/pdf/317730PAPER0SDP770conflict0WP0211web.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Richards, P. To fight or to farm? Agrarian dimensions of the Mano River conflicts (Liberia and Sierra Leone). Afr. Aff. 2005, 105, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utas, Mats. Building a Future? The Reintegration and Remarginalization of Youth in Liberia. In No Peace No War: An Anthropology of Contemporary Armed Conflicts; Richards, P., Ed.; Ohio University Press: Athens, Greece, 2005; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=3U80lcHx94oC&lpg=PA1&ots=oEztzoCaYN&lr&pg=PA242#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Scarborough, G. Growing a Future: Liberian Youth Reflect on Agriculture Livelihoods. USAID, Mercy Corps. Available online: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/Liberian-Youth-Reflect-on-Agriculture-Livelihoods-Mercy-Corps-2017_0.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Brottem, L.; Unruh, J. Territorial tensions: Rainforest conservation, postconflict recovery, and land tenure in Liberia. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2009, 99, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloh, O.; Yarsiah, J.; Otto, J. Individual Land Ownership Versus Collective Land Ownership. Current Practices, Opportunities, Challenges & Options. Report Prepared for the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI). Available online: https://www.sdiliberia.org/sites/default/files/publications/SDI%20Report%20Individual%20Land%20Ownership%20Versus%20Collective%20Land%20Ownership.compressed.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Knight, R.; Kpanan’Ayoung Siakor, S.; Kaba, A. Protecting Community Lands and Resources: Evidence from Liberia; Report prepared by Namati, Sustainable Development Institute, and IDLO; Available online: https://namati.org/resources/protecting-community-lands-and-resources-evidence-from-liberia/ (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Liberia News Agency [AllAfrica]. All Africa Bong Youth Wants Govt Intervene in Fuamah Land Conflict. Available online: allafrica.com (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Daffah, M. Liberia: Youths seek global intervention for resolution of Nimba land dispute. In BBC Monitoring International Reports; Text of Report Published by Liberian Non-State Station Star Radio Website; 29 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Urey, E.K. Political Ecology of Land and Agriculture Concessions in Liberia; The University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, E.; Teage, C.; Dodd, M.; Urey, E.; McClung, M. A Report on High Level Findings from Research on Women’s Participation in Forest Governance Bodies in Nimba, Grand Bassa and Margibi Counties; Landesa: Seattle, CA, USA, July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee, T.; Krawczyk, L.; Krumrei, K.; McCachren, C.; Raval, N.; Visser, C. Youth to Youth: Measuring Youth Engagement Liberia. Report Prepared by Search for Common Ground, Liberia’s Ministry of Youth & Sports, and American University. Available online: https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Youth_Engagement_Report_Full.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Williams, C.A.; Ocha, G.B. Land ownership for youth in agriculture: A case study of Bolivia, Brazil and Liberia. [Presentation]. Presented at the World Bank Land and Poverty Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 23–27 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Blattman, C.; Annan, J. The consequences of child soldiering. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2010, 92, 882–898. Available online: https://www.chrisblattman.com/documents/research/2010.Consequences.RESTAT.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, F. The Pivot to Yes: Positive Youth Development and Our Agriculture Program in Liberia. [Blogpost]. Making Cents International. Available online: http://www.youthpower.org/resources/making-cents-blog-pivot-yes-positive-youth-development-and-our-agriculture-program-liberia (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Making Cents. Our Work Projects. Liberia Agriculture, Upgrading Nutrition, and Child Health (LAUNCH). Client: ACDI/VOCA (USAID). Available online: http://www.makingcents.com/liberialaunch (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- USAID. Liberian Youth and Agriculture: Building a Food Secure Future in Liberia through Youth Entrepreneurship. [Power Point Presentation]. 2016 Global Youth Economic Opportunities Summit. Available online: https://youtheconomicopportunities.org/sites/default/files/uploads/resource/Changing%20Youth%E2%80%99s%20Perceptions%20of%20Agriculture%20Experiences%20from%20Liberia.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

| 1 | Although this age range is generally accepted as a definition of youth, in reality there are wide range of social factors that define youth and adulthood in rural communities in Liberia. The Government of Liberia in its National Youth Policy defines Liberian youth as being between the ages of 15 and 35 (Brownlee et al., 2012), a definition also used by the African Youth Charter (2006) and the National Federation of Liberian Youth (Nasser 2012). |

| 2 | “Strangers” are residents who are not in the direct landowning lineages of communities in Liberia. Usually they have various degrees of land-use rights but not ownership rights. Some of them, especially youth, are born in the communities, but because their parents are not in the landowning lineage they are often referred as strangers and have less secure land access and land rights. |

| 3 | The framework has gone through several iterations with contributions made by different stakeholders in the land sector. A version of the framework was used by Doss and Meinzen-Dick (2018), who cite Place et al. (1994) as originating the approach. An version of the framework was also used by Landesa to examine women’s land rights in Myanmar, see Louis, Eshbach, Roberts and Htee (2018) “An assessment of land tenure regimes and women’s land rights in two regions of Myanmar”, Paper Presented at the World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. Washington, D.C. March 2018. |

| 4 | Under the LRA, a youth may legally qualify as a community member if he or she is a Liberian citizen and who fits in any one of the follow categories: (i) born in the community, (ii) parent(s) was born in the community, (iii) community resident of 7 years, or (iv) spouse of a resident community member (inclusive of statutory, customary, and presumptive spouses) (art. 2). |

| 5 | “Persons who live together as husband and wife and hold themselves out as such are presumed to be married” (Civil Procedure Law, § 25.3(3)). |

| 6 | Tribal Certificates are an initial step for registering land but until it is transformed into a deed, the land rights are only usufruct (use rights). |

| 7 | For example, as opposed to being enforceable only after the completion of an administrative process. |

| 8 | Although land can be taken if the community provides the community member with comparable land. |

| 9 | Under the LRA, alternative dispute resolution mechanism is defined as any process used to resolve disputes outside of court, and alternative dispute resolution body is defined as any entity, including a customary body, whose purpose is to resolve disputes outside of court (art. 2). |

| 10 | These responses are for a question asked about ‘big’ land decisions,’ i.e., regarding land over 50 acres; responses were nearly identical on a question about land under 50 acres—The only exception being that when it came to decisions about small parcels, about 5% said the family/clan made land decisions. |

| Community | No. of Respondents | Male | Female | Adult | Youth * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lofa County | 85 | 62% | 38% | 49% | 51% |

| Pasama | 36 | 47% | 53% | 42% | 58% |

| Bardezu | 24 | 29% | 71% | 79% | 21% |

| Gbonyea | 25 | 32% | 68% | 32% | 68% |

| Bong County | 73 | 41% | 59% | 47% | 53% |

| Gbarnga Siaquelleh | 36 | 50% | 50% | 44% | 56% |

| Shankpowai | 37 | 67% | 33% | 50% | 50% |

| Rivercess County | 50 | 30% | 70% | 82% | 18% |

| Neezuin | 25 | 32% | 68% | 80% | 20% |

| Little Liberia | 25 | 28% | 72% | 84% | 16% |

| Total | 208 | 43% | 57% | 57% | 43% |

| Land Rights Dimension | Definition | Questions Used to Analyze Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Completeness | Whether the bundle of rights enjoyed by an individual or group is clearly defined and enforced in all its dimensions for all members of a community, including those who may have new rights to that land | (1) Are the rights for female and male youth clearly defined under the LRA and related laws that govern land rights? (2) Do female and male youth and others have knowledge of youth land rights, and (3) Are female and male youth able to realize their rights? |

| Robustness | Whether rights can be enforced in the face of contestation | (1) Does the LRA clearly define enforcement of rights for female and male youth in the face of contestation, (2) Do female and male youth know how to enforce their rights in the face of contestation, and (3) Are female and male youth able to enforce their rights in the face of contestation. |

| Gender Equitable | Whether the land rights system give all the ability to participate in decisions about the land | (1) Does the LRA clearly define land rights/land governance as inclusive and gender-equitable, (2) Do youth understand their rights as they relate to decision-making on land governance? (3) Are youth able to participate in land decisions at the community level? |

| Inclusive |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Louis, E.; Mauto, T.; Dodd, M.-L.; Heidenrich, T.; Dolo, P.; Urey, E. Using a Gender-Responsive Land Rights Framework to Assess Youth Land Rights in Rural Liberia. Land 2020, 9, 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9080247

Louis E, Mauto T, Dodd M-L, Heidenrich T, Dolo P, Urey E. Using a Gender-Responsive Land Rights Framework to Assess Youth Land Rights in Rural Liberia. Land. 2020; 9(8):247. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9080247

Chicago/Turabian StyleLouis, Elizabeth, Tizai Mauto, My-Lan Dodd, Tasha Heidenrich, Peter Dolo, and Emmanuel Urey. 2020. "Using a Gender-Responsive Land Rights Framework to Assess Youth Land Rights in Rural Liberia" Land 9, no. 8: 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9080247