Gatekeeping Access: Shea Land Formalization and the Distribution of Market-Based Conservation Benefits in Ghana’s CREMA

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

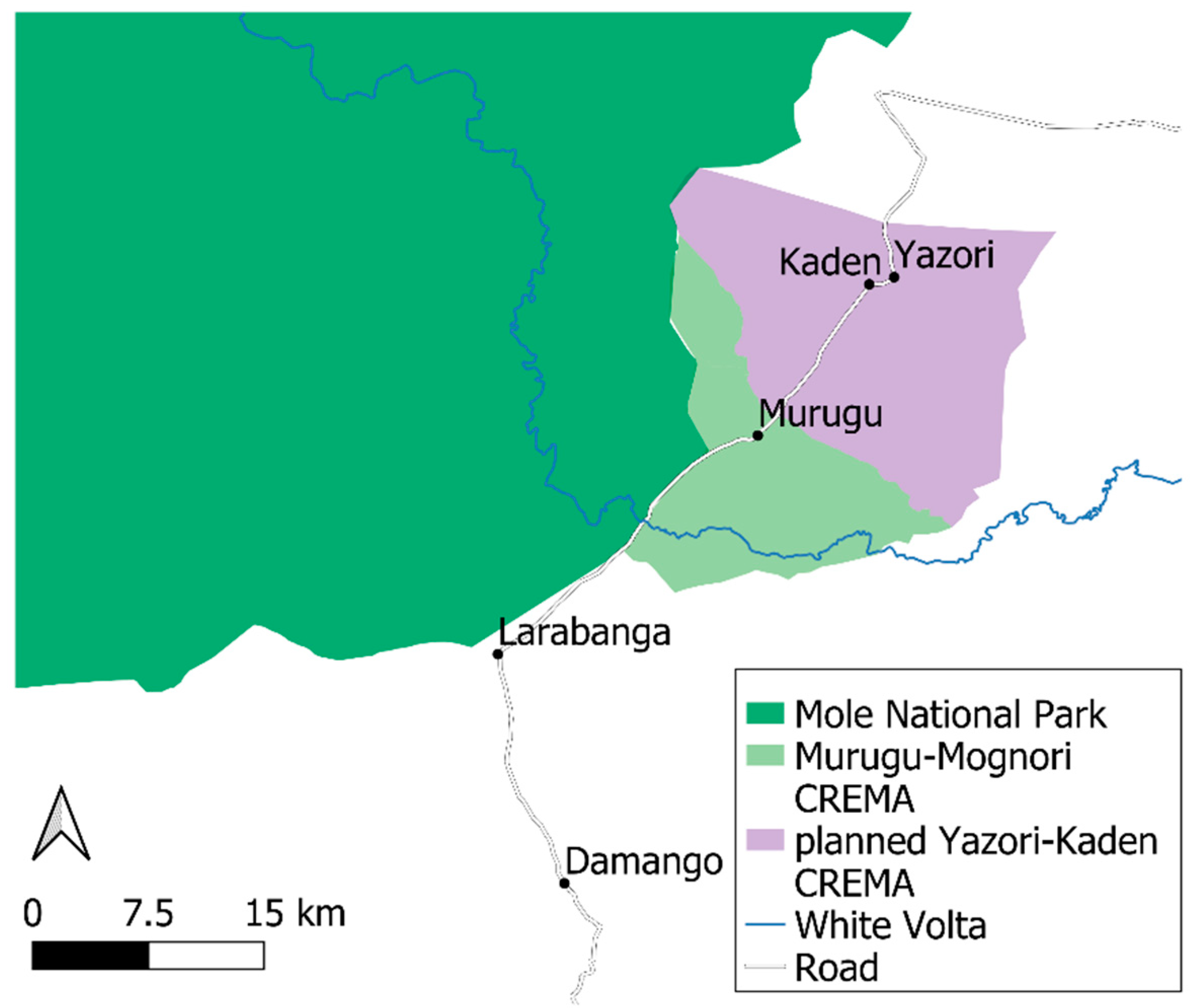

3.1. Contextualising the Case Study

Conservation, Displacement, and Shea Land Formalization in the Mole Area

3.2. Beyond a Market Logic: Contrasting Narratives of CREMA Legitimation

3.3. Traditional Authorities and NGOs Producing the Winners and Losers of Shea Land Formalisation

3.3.1. Improving Shea Benefits in Murugu

3.3.2. Exclusion from Organic Shea Benefits in Kaden

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roe, D. Community Management of Natural Resources in Africa: Impacts, Experiences and Future Directions; IIED: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84369-755-8. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, M. Effect of Institutional Choices on Representation in a Community Resource Management Area in Ghana; Responsive Forest Governance Initiative Working Paper Series; Murombedzi, J., Ribot, J., Walters, G., Eds.; IUCN, University of Illinois, and the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA): Dakar, Senegal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baruah, M. Facipulation and elite formation: Community resource management in Southwestern Ghana. Conserv. Soc. 2017, 15, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechin, S.R. Contested Nature: Promoting International Biodiversity with Social Justice in the Twenty-First Century; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7914-5775-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shanley, P. Tapping the Green Market: Certification and Management of Non-Timber Forest Products; People and Plants Conservation Series; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-85383-871-2. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, R.J.; Dressler, W. Market-oriented conservation governance: The particularities of place. Geoforum 2012, 43, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Hirsch, P.; Li, T. Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast. Asia; University of Hawai Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8248-3603-0. [Google Scholar]

- Heynen, N. (Ed.) Neoliberal Environments: False Promises and Unnatural Consequences; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-415-77148-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R. Neoliberal environmentality: Towards a poststructuralist political ecology of the conservation debate. Conserv. Soc. 2010, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, R.A.; Kyei, A.; Mason, J.J. The community resource management area mechanism: A strategy to manage African forest resources for REDD+. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wardell, D.A.; Lund, C. Governing access to forests in northern Ghana micropolitics and the rents of non-enforcement. World Dev. 2006, 34, 1887–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, E.; Dearden, P.; Rollins, R. Nature-based tourism in Mole National Park, Ghana. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2016, 35, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzekoto, G.E.; Bosu, D. Community resource management areas (CREMAs) in Ghana: A promising framework for community-based conservation. In World Heritage for Sustainable Development in Africa; Moukala, E., Odiaua, I., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wardell, A.; Fold, N. Globalisations in a nutshell: Historical perspectives on the changing governance of the shea commodity chain in northern Ghana. Int. J. Commons 2013, 7, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfin, B. Shea Butter Republic: State Power, Global Markets, and the Making of an Indigenous Commodity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-415-94460-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, K. Political Ecology du Karité: Relations de Pouvoir et Changements Sociaux et Environnementaux Liés à la Mondialisation du Commerce des Amandes de Karité Cas de l’Ouest du Burkina Faso; ParisTech: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal, M. Tree Tenure in Agroforestry Parklands: Implications for the Management, Utilisation and Ecology of Shea and Locust Bean Trees in Northern Ghana; University of York: York, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, G. Opportunities for Interventions around Mole National Park which both Enhance Livelihoods and Promote REDD+ Agendas; International Union for Conservation of Nature and A Rocha: Accra, Ghana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lovett, P.N. The shea butter value chain: Production, transformation and marketing in West Africa. West. Afr. Trade Hub Tech. Rep. USAID 2004, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier de Sardan, J.-P.; Bierschenk, T. Les courtiers locaux du développement. Bull. L’APAD 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosse, D.; Lewis, D. Theoretical approaches to brokerage and translation in development. In Development Brokers and Translators: The Ethnography of Aid and Agencies; Lewis, D., Mosse, D., Eds.; Kumarian Press Inc.: West Hartford, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Büscher, B.; Fletcher, R. The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature Beyond the Anthropocene; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78873-770-8. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, M.; Arora-Jonsson, S. Negotiating across difference: Gendered exclusions and cooperation in the shea value chain. Environ. Plan. D 2017, 35, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nightingale, A.J. Bounding difference: Intersectionality and the material production of gender, caste, class and environment in Nepal. Geoforum 2011, 42, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoding, J.; Walters, G.; Andama, R.; Carvalho, S.; Colomer, J.; Cracco, M.; Eilu, G.; Gaster Kiyingi, K.; Kumar, C.; Langoya, C.D.; et al. Analysing and Applying Stakeholder Perceptions to Improve Protected Area Governance in Ugandan Conservation Landscapes. Land 2020, 9, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolwig, S.; Ponte, S.; Du Toit, A.; Riisgaard, L.; Halberg, N. Integrating Poverty and Environmental Concerns into Value-Chain Analysis: A Conceptual Framework. Dev. Policy Rev. 2010, 28, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, L.D.; Kitchin, R.; Thrift, N. Discourse analysis. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elselvier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Okoro, J.A. Reflections on the Oral Traditions of the Nterapo of the Salaga Area. Hist. Afr. 2008, 35, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaku Brukum, N.J. The Northern Territories of the Gold Coast under British Colonial Rule, 1897–1956: A study in Political Change; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Haight, B.M. Bole and Gonja Contributions to the History of Northern Ghana; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sobey, D.G. Anogeissus groves on abandoned village sites in the Mole National Park, Ghana. Biotropica 1978, 10, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grischow, J.D. Late colonial development in British West Africa: The Gonja development project in the Northern territories of the Gold Coast, 1948-57. Can. J. Afr. Stud. Rev. Can. Études Afr. 2001, 35, 282–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardell, A. Groundnuts and headwaters protection reserves. Tensions in colonial forest policy and practice in the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. In Commonwealth Forest & Environmental History. Empire Forests and Colonial Environments in Africa, the Caribbean, South Asia and New Zealand; Damodan, V., D’Souza, R., Eds.; Primus Books: Delhi, India, 2020; pp. 357–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L.W.; Sasu, K.A. The role of values in a community-based conservation initiative in Northern Ghana. Environ. Values 2013, 22, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestry Commission. Mole National Park Management Plan; Republic of Ghana: Accra, Ghana, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Acquah, E.; Rollins, R.; Dearden, P.; Murray, G. Concerns and benefits of park-adjacent communities in Northern Ghana: The case of Mole National Park. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2017, 24, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.; Danso, E. PRA for people and parks: The case of Mole National Park, Ghana. PLA Notes 1995, 22, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, F. Community Rights, Conservation and Contested Land: The Politics of Natural Resource Governance in Africa; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84407-916-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius, C.; Koch, E.; Turner, S.; Magome, H. Rights, Resources and Rural Development: Community-Based Natural Resource Management in Southern Africa; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-84407-010-7. [Google Scholar]

- Adjei, P.O.-W.; Agyei, F.K.; Adjei, J.O. Decentralized forest governance and community representation outcomes: Analysis of the modified taungya system in Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C. Who owns Bolgatonga? A story of inconclusive encounters. In Land and the Politics of Belonging in West Africa; Kuba, R., Lentz, C., Eds.; Brill Academic Publishers, Incorporated: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, S. No Condition is Permanent: The Social Dynamics of Agrarian Change in Sub-Saharan Africa; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ubink, J.M.; Amanor, K. Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana: State, Chief and the Citizen; Law, Governance, and Development Research; Leiden Univ. Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008; ISBN 978-90-8728-047-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, M.P.; McShane, T.O.; Dublin, H.; O’Conner, S.; Redford, K.H. The future of integrated conservation and development projects: Building on what works. In Getting Biodiversity Projects to Work: Towards More Effective Conservation and Development; McShane, T.O., Wells, M.P., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, G. Conservation Jujutsu, or how conservation NGOs use market forces to save nature from markets in Southern Chile. In The Anthropology of conservation NGOs; Larsen, P., Brockington, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, J.C.; Chhatre, A.; Lankina, T. Introduction: Institutional choice and recognition in the formation and consolidation of local democracy. Conserv. Soc. 2008, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Apusigah, A.A. The gendered politics of farm household production and the shaping of women’s livelihoods in Northern Ghana. Fem. Afr. 2009, 12, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.; Mariwah, S.; Barima Antwi, K. Struggles over family land? Tree crops, land and labour in Ghana’s Brong-Ahafo region. Geoforum 2015, 67, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wet, J.P. ‘We don’t want your development!’: Resistance to imposed development in Northeastern Pondoland. In Rural Resistance in South Africa: The Mpondo Revolts after Fifty Years; Kepe, T., Ntsebeza, L., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Husseini, R.; Kendie, S.B.; Agbesinyale, P. Community participation in the management of forest reserves in the Northern Region of Ghana. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, K.; Gautier, D.; Wardell, D.A. Renegotiating access to shea trees in Burkina Faso: Challenging power relationships associated with demographic shifts and globalized trade: Renegotiating access to shea trees in Burkina Faso. Agrar. Chang. 2017, 17, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, N.L.; Lund, C. New frontiers of land control: Introduction. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putzel, L.; Kelly, A.B.; Cerutti, P.O.; Artati, Y. Formalization as development in land and natural resource policy. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 28, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pierce, A.R. Social issues. In Tapping the Green Market: Certification and Management of Non-Timber Forest Products; Laird, S.A., Guillen, A., Pierce, A.R., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2002; pp. 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, L.A.; Arts, K.; Turnhout, E. From rationalities to practices: Understanding unintended consequences of CBNRM. Conserv. Soc. 2020, 18, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P. Is small really beautiful? Community-based natural resource management in Malawi and Botswana. World Dev. 2006, 34, 1942–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | It is not known if such a Commission was established for the creation of Mole National Park or the preceding reserve. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gilli, M.; Côte, M.; Walters, G. Gatekeeping Access: Shea Land Formalization and the Distribution of Market-Based Conservation Benefits in Ghana’s CREMA. Land 2020, 9, 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9100359

Gilli M, Côte M, Walters G. Gatekeeping Access: Shea Land Formalization and the Distribution of Market-Based Conservation Benefits in Ghana’s CREMA. Land. 2020; 9(10):359. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9100359

Chicago/Turabian StyleGilli, Mengina, Muriel Côte, and Gretchen Walters. 2020. "Gatekeeping Access: Shea Land Formalization and the Distribution of Market-Based Conservation Benefits in Ghana’s CREMA" Land 9, no. 10: 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9100359

APA StyleGilli, M., Côte, M., & Walters, G. (2020). Gatekeeping Access: Shea Land Formalization and the Distribution of Market-Based Conservation Benefits in Ghana’s CREMA. Land, 9(10), 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9100359