Abstract

The historical progress of Hagia Sophia encompasses four different periods. Dating back to 360 AD, this unique structure was the largest church built in Istanbul during the Roman Period. In the second period, Fatih Sultan Mehmet conquered Istanbul in 1453 and personally dedicated Hagia Sophia to his foundation as a mosque. In the third period, upon the founding of the modern Republic of Turkey, Hagia Sophia was transformed into the Museum in 1934. Finally, in 2020, the structure was converted once again to a mosque by a court decision. Ongoing discussions today have suggested that the structure be used as a mosque, a church, or a museum. In this study, the ownership rights of the monument and its cultural heritage status have been examined within the framework of rulings of the European Court of Human Rights. The study evaluates the 1934 decree preventing the owner of the property rights from being given authorization over the monument. The results indicate that there was a legal obligation to grant the use of Hagia Sophia/Ayasofya as a mosque in accordance with the property rights of Fatih Sultan Mehmet, who proclaimed the establishment of its foundation.

1. Introduction

The name Hagia Sophia is derived from the combination of the ancient Greek ’hagia’, which means ’sacred’ or ’saint’, and ’sophia’, which is the word for ’wisdom’. Hagia Sophia (“Ayasofya” in Turkish) in Istanbul was the largest church built by the Eastern Roman Empire and was erected three times in the same place. It was first built in 360 AD by Emperor Constantius, son of Constantine. Although the building was first known as the “Great Church” (Megali Ekklesia), the name Hagia Sophia was also used for the edifice in the following period [1]. The first church was burned down in the popular revolt during the reign of Saint Yohannes Khyrsostomos, the patriarch of Constantinople. A new church was built by the Emperor Theodosius II in 415. The second church was destroyed in 532 during the Nika revolt. Today’s Hagia Sophia was built during the reign of Emperor Justinian (527–565) by two important architects, Isidoros and Anthemios. The church was opened for worship on 27 December 537. After the Fourth Crusade, Istanbul was occupied by the Latins between 1204 and 1261. In this period, both the city and the Hagia Sophia church were looted. Hagia Sophia was in a very dilapidated state when the Eastern Roman Empire took over the city again in 1261 [2]. With the conquest of Istanbul in 1453, Hagia Sophia was transformed into a mosque and was established as a charity foundation by Fatih Sultan Mehmet. Since 1453, many additions have been made to the interior and exterior of the building. In particular, the interventions carried out by Mimar Sinan played an important role in the work’s survival to date.

In the early years of the Republic of Turkey, American Byzantine Institute founder Thomas Whittemore aspired to work on the restoration and received the necessary permits in 1931. During the time of the restoration, the transformation of Hagia Sophia into a museum was brought to the agenda and finally, with the decree of the Council of Ministers dated 24 Novenber 1934 and numbered 2/1589, Hagia Sophia was converted to a museum. The monument, which had been closed on 9 December 1934 due to repairs, was opened to visitors on 1 February 1935 with a new identity [2,3] (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The decision taken under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in the first years of the Republic was undeniably an administrative decision. It is possible to come across similar administrative decisions during these years (for example, the transformation of the Kariye Mosque into a museum in 1945). Such decisions are undoubtedly the result of the policies implemented in the early Republican period, which represents the first 20–25 years of the Republic.

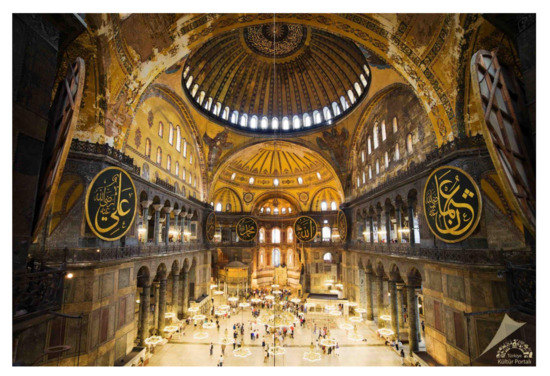

Figure 1.

Interior of Hagia Sophia [4].

However, the transformation of the monument into a museum has led to many years of controversy. Each segment of society assigned a function to Hagia Sophia in line with its own political ideas and became a partner in the discussion. This discussion continued at an academic level as well. For example Aykaç (2018) stated that it was common practice to convert Byzantine monuments into museums in the first years of the Republic. She argued that these museums were instrumental in alienating the secular nation-state from its imperial and Islamic Ottoman past and presented an official narrative of the early Republican ideology. In the same study, she maintained that the conversion of these works to mosques was a manifestation of the current political environment challenging the secular republic. In summary, with these and similar comments, those who are against Hagia Sophia operating as a mosque emphasize that the work has a multi-layered identity, that it has a symbolic meaning for diverse groups and in this way represents the secular republic [5].

On the other hand, those who emphasize that Hagia Sophia should be used as a mosque claim that the work was transformed into a mosque with the conquest, within the framework of the legal norms of the period [6], and that since then, as a result of repairs, support, and other activities the monument, has acquired the identity of a Turkish work of art [7]. They also maintain that it is a direct manifestation of the sovereign rights of the country [8] and that the work should be used as a mosque in accordance with the deed of trust as a requirement under domestic law [9].

In 2020, an organization dedicated to preserving the cultural assets of the foundation filed a lawsuit against the Presidency in order to overturn the 1934 decision of the Council of Ministers that transformed Hagia Sophia into a museum. The Council of State annulled the 1934 decision based on various legal grounds and precedent decisions. The reasons for the decision will be discussed in detail later in the article.

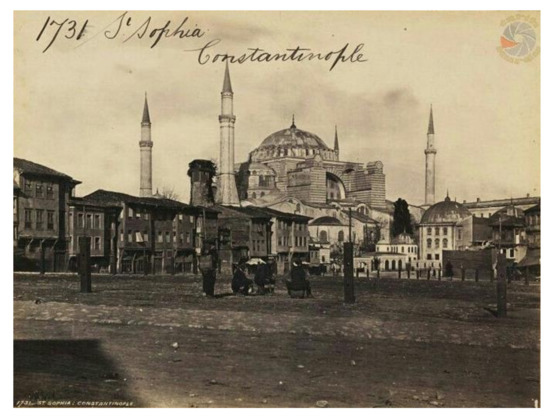

Figure 2.

Photograph of Hagia Sophia from the year 1850 [10].

As can be understood from the process summarized above, the debates on the status of Hagia Sophia are largely based on religious or political grounds, even at an academic level. Each of these views is valuable. However, the literature study presented above illustrates that this problem has not been addressed within a legal framework. Thus, how should the edifice be used according to national and international legal norms? In this study, this issue will be addressed by taking into account only the legal status of Hagia Sophia, apart from political or religious motives. Accordingly, the restrictions on the rights of use, beneficial ownership, and authority arising from the property rights of the monument will be evaluated within the framework of national and international legal principles.

2. Material and Methods

In this article, the discussions on the use of Hagia Sophia, as a cultural asset belonging to a fused foundation, will be analyzed within the framework of property rights. Therefore, the basis of the discussion will include property rights, international conventions, foundation ownership and cultural property legislation, especially as the subject of domestic law, and the role of the Directorate General of Foundations (Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü—VGM). Without understanding these concepts, it is not possible to present the debate on accurate grounds. This lack of knowledge is a significant problem existing at a national level, not to mention at an international level. Indeed, according to the results of the project conducted by Çoruhlu et al. (2020) and supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey, it was found that the basic concepts of the Law on Foundations are not clearly understood and that there are misconceptions, even at an academic level. For this reason, first of all in the article, the abovementioned issues will be clarified. In the next section, the ownership status of Hagia Sophia will be investigated and the results presented. In the Discussion section, the decision that transformed Hagia Sophia into a museum will be discussed under various headings, taking the standards of domestic and international law into account, and the results presented. In this respect, the study is not only a research article, but also a case study of Hagia Sophia and a precedent for works with similar features [11].

2.1. Right to Property

The right to property is the real right that gives the owner the rights of usage, beneficial ownership, and authority. The right to property, which is defined as an unlimited real right, also imposes some obligations/limitations and authority/powers on the property owner. The owner has the opportunity to dispose of the property as he wishes. With this authority, which is known as active authority, the owner can dispose of it as he wishes, as prescribed by law. The right to property is a right guaranteed by international declarations and contracts. On 10 December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly (including the consent of Turkey) adopted Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [12], expressed as: “Everyone has the right to own property alone or in association with others. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.”

Regarding the protection of fundamental freedoms, the Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) was signed in Rome on 4 November 1950. Turkey is a signatory and is committed to the regulations on the right of property in Appendix 1, Article 1 of the ECHR Protocol: “Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions. No one shall be deprived of his possessions except in the public interest, the conditions provided for by law and the general principles of international law” [13]. Since 1987, the government of the Republic of Turkey has recognized the right of individual Turkish citizens to petition the European Court of Human Rights.

According to the article 90/4 of the Turkish Constitution, “International agreements duly put into effect have the force of law. No appeal to the Constitutional Court shall be made with regard to these agreements on the grounds that they are unconstitutional. In the case of a conflict between international agreements, duly put into effect, concerning fundamental rights and freedoms and the laws, due to differences in provisions on the same matter, the provisions of international agreements shall prevail.” For these reasons, the subject of this study includes the regulations in the Turkish legal system regarding European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) decisions made according to Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms [13].

The court not only imposes the ECHR’s obligation not to interfere with the rights and freedoms of individuals, but also requires that the necessary measures be taken to ensure that these rights and freedoms can actually be used effectively [14]. The ECtHR’s acknowledgment that the State also has positive obligations came after the 1968 Belgian Language Case [15]. Likewise, it was asserted that the State did not fulfill its positive obligation in the Öneryıldız v. Turkey decision. The duty of the State is to guarantee the rights and freedoms given to individuals. In addition, the right of individuals to demand respect for the immunity of possessions stated in Article 1 of Protocol 1 protects individuals against unfair interference by the State [16]. Similarly, the Turkish legal system has recognized that the property owner has the same active authority and protective powers.

2.2. Right to Property in the Turkish Land Administration System

Traditionally, in the region where Turkey is located, there is an understanding of land ownership that takes its source from Islamic Law. Islamic Law adopts an understanding that emphasizes a social approach rather than an individualistic approach to land ownership [17]. The Ottoman Empire, in general, established its own land ownership system and thus, its economy was shaped in accordance with the principles of Islamic Law [18]. The Land Code (1858) of the Ottoman Empire classified land groups as: mülk (private property with limited ownership), mîrî (large agricultural lands owned by the State), vakıf (foundation land), metrûk (pasture lands and such allocated for public use), and mevât (non-arable land such as stony terrain and swamps) [18,19,20,21]. One of the most important land classes under the Ottoman land regime was undoubtedly foundation land, which comprises the subject of this study [22]. The effort to return individual property, which began in the last period of the Ottoman State, gained momentum with the declaration of the Republic (1923) and the enactment of the Turkish Civil Code (TMK in Turkish) in 1926. The cadastral laws that came into force after this date have played an important role in the establishment of an individual property-based land registry system [23].

Today, the Turkish legal system has adopted a mixed view of property rights. Both private property and State ownership form the basic principles of this system. The Constitution of the Republic of Turkey (1982), according to Article 35, states: “Everyone has the right to own and inherit property. These rights may be limited by law only in view of public interest. The exercise of the right to property shall not contravene public interest” [24]. In Article 683 of the Turkish Civil Code, this provision is included: “The owner of a property is entitled to use, benefit, and dispose of such property in whatever way he wishes within the boundaries of the order of laws” [25]. By reason of the legal norms listed above, everyone in the country has the right to property according to constitutional norms. However, in the public interest, private property can be translated to a price and expropriated by the State.

Restriction of the right to property and confiscation are the main problems related to property ownership [11]. Such restrictions sometimes arise from laws (e.g., on Zoning, Conservation of Cultural and Natural Assets, Foundations, etc.), sometimes from the zoning plan, and sometimes from administrative decisions. The legal compliance of these restrictions is important. For this reason, the concept of confiscation without expropriation was introduced into the Turkish legal system for the first time in 1956 [26]. On the other hand, in 2010, the right of individual application to the Constitutional Court was granted. This right has provided the opportunity to examine many issues regarding property rights under high-level jurisdiction [27].

2.3. Foundation and Foundation Real Estate

In the Ottoman land system, foundations attracted attention both as charities and as a property type. In this period, the most important component of the land classes was the mîrî lands (cultivated agricultural lands) together with the foundation lands [28]. The most widespread definition of foundation ownership is the removal of the right of use as individual property and the dedication of it to the public interest forever. In Turkish, vakfiye refers to the document stating the terms of a foundation. After the Republic, this document was defined as a “foundation certificate” [29].

Coruhlu (2013) reported that, especially with Islam, the phenomenon of the foundation was completely established over a wide region and played an influential role in social and economic life. The concept of the foundation witnessed its golden age with the establishment of the Ottoman State. Almost every transaction, except in the internal and external security services and State management, was carried out through foundations [30]. In the Ottoman State, the income-generating real estate of the foundations, including land, estates, buildings, and inns, was known as akar [31]. Income from these immovable properties was used to fulfill the conditions of the foundation. There were also immovable properties such as mosques, cemeteries, and fountains that were referred to as charity (hayrat) real estate without income-generating features. These were properties providing community services free of charge and not bringing any income. All expenses were covered by the income-generating real estate [32].

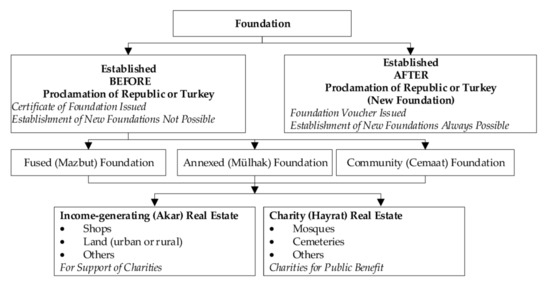

Today, foundations in Turkey are discussed under two headings: those established before and after the Republic (Figure 3). In terms of the administration of foundations established before the Republic, the foundations were divided into three types: mazbut (fused), mülhak (annexed), and cemaat ve esnaf (community and tradesmen) foundations. Since the annexed foundations and community and tradesmen foundations are governing bodies, they carry out their own management and representation. However, since there are no managers or trustees for the fused foundations, their management and representation are conducted by the VGM [29]. Today, no new fused foundations are being established. No administrators can be appointed to fused foundations, nor trustees created. The legal status of these foundations, which are private legal entities, cannot be removed. The real estate owned by these foundations belongs only to these foundations, not to the State or the VGM [30]. Today, all the real estate and charity properties of the fused foundations are recorded in the VGM foundation Immovable Property Registry, similar to those recorded in the Land Registry. The tracking of these records is carried out by the VGM with the utmost care.

Figure 3.

Types of Foundations in Turkey (Adapted from [11]).

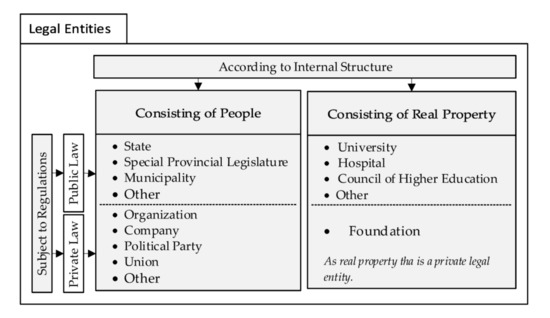

Today, according to the internal structure of the Turkish legal system, depending on the regulations they are subject to, foundations are a legal entity under private law (Figure 4). The reasons for establishing foundations cannot go against public interest or community benefit. Foundations must own movable or immovable property in order to provide services suited to the purposes for their establishment. They serve their establishment objectives with the income collected from these assets.

Figure 4.

Legal entity of foundations (Adapted from [11]).

2.4. Cultural Assets and Directorate General of Foundations

Today, there are over 100 thousand immovable cultural assets in Turkey [33]. The most important one of them is maybe Hagia Sophia (Figure 5). The Ministry of Culture and Tourism is responsible for the business and transactions of immovable cultural assets and sites, while local governments are the main actors in the development and management of the zoning plans. In the event that there are protected areas in the region to be planned, there is an imperative to make a zoning plan for conservation purposes [34]. The authority in the protected areas belongs to the local governments and the Regional Council for Protection of Cultural Heritage. A zoning plan for protected areas cannot be implemented without the approval of the Council. Local governments are responsible for the execution of all business and transactions according to these approved plans.

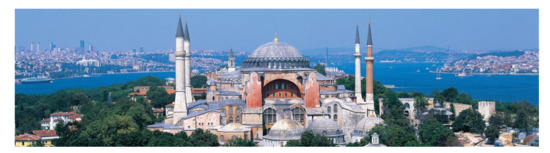

Figure 5.

Exterior view of Hagia Sophia [35].

Turkey joined the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage (adopted in 1972) in 1982 [36]. After that Law on the Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage (KTVKK) (No. 2863) came into force [37].

According to Article 7 of the KTVKK: “Immovable cultural and natural property owned by fused foundations is administered and controlled by the VGM.” Article 10 states: “The protection and evaluation of the cultural and natural assets belonging to the fused foundations under the administration and supervision of the VGM are carried out by the VGM, after the decision of the Conservation Councils.” Moreover, this provision is included in Article 11: “The owners shall exercise all their rights of ownership and powers pertaining to the property as long as these do not conflict with the provisions of this law” [37].

According to article 14 of the same law, in order to be used in public service, the VGM is authorized to maintain the usufruct rights of immovable cultural and natural assets belonging to the fused and annexed foundations, or to rent them on condition that they are used in accordance with their character. Article 15, paragraph a/2 states: “Public institutions and organisations, municipalities, special provincial administrations and unions of local administrations can expropriate registered immovable cultural properties provided these are used in line with the functions prescribed by Regional Conservation Councils.” From this it is understood that even if public institutions expropriate an immovable cultural asset, it cannot be used outside the function determined by the Conservation Council.

However, there is no such function condition for the protection and evaluation of cultural assets of the fused foundations under VGM management and representation. Only in Article 7 of the law is found the phrase: “after the decision prescribed by Regional Conservation Councils.” Again, in Article 11 it is stated that that the owner of this type of immovable cultural property can exercise all powers entailed by property rights and that are not in contradiction with the KTVKK. In line with all these data, it can be surmised that the Conservation Council does not have the authority to give a function to the immovable cultural assets of a foundation.

2.5. ECtHR Point of View on Foundation Ownership and Foundation Real Estate Based on the Ottoman Period

The ECtHR ruled that the State was obliged to restore pre-violation legal status to the plaintiff in a 1999 decision [38]. On the other hand, the ECtHR stated that there is a procedure that must be followed by the defendant State in order to eliminate the violation, and if, for example, the real estate in question is in accordance with its particular characteristics, i.e., religious facilities and cemeteries, the most appropriate compensation method may possibly be for the defendant to re-register this property in the name of the plaintiff as soon as possible [39,40].

For a better understanding of foundation ownership, it is useful to look at some precedent decisions. One of them is the case of the Fener Greek Boys’ Secondary School Foundation (Fener Rum Erkek Lisesi Vakfı) v. Turkey (dated 20 September 2005; application no. 34478/97). This foundation was established at the time of the Ottoman Empire and set up to provide educational facilities at the Greek Higher Secondary School in Fener (Istanbul). In 1952 the Fener Greek Boys’ Secondary School Foundation received a gift of part of a building in Istanbul. It purchased another part of the building in 1958. However, a lawsuit was filed by the treasury claiming that the relevant foundation was not eligible to acquire real estate. After the domestic legal process was completed, an application was made to ECtHR by the foundation. As a result of the trial, the ECtHR decided that the interference with the foundation property was incompatible with the principle of legitimacy [41].

The case of the Fener Greek Patriarchy v. Turkey (dated 8 July 2008; application no. 14340/05) is another example. The decision drew attention to a number of points. The applicant, the Fener Greek Patriarchate, is an Orthodox church in Istanbul. The case concerned the annulment by the Turkish authorities of the applicant church’s title to certain real property. In January 1902 the Patriarchate acquired the real property using its own capital. In 1903 a foundation of the Orthodox minority, the Foundation of the Büyükada Greek Orphanage for Boys (the “Orphanage Foundation”), was given the use of the property. When the Foundations Act came into force on 13 June 1935, the legal status of the Orphanage Foundation was officially recognized, and the property concerned was mentioned in the declaration registered by it in 1936. On 22 January 1997, the VGM changed the status of the Orphanage Foundation from an annexed foundation to a fused foundation. Thus, the management of the foundation passed to the VGM. After completion of the domestic legal procedures, the ECtHR held unanimously that there had been a violation of Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 (protection of property) and stated: “Therefore, the property has to be re-registered to the respondent within three months by the State” [42].

3. Results

In this section, the ownership, zoning plan, and foundation document of Hagia Sophia are presented.

Analysis of Ownership: Land Registry and Foundation Registry

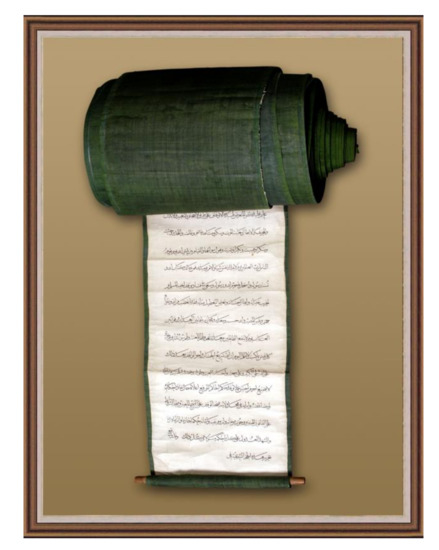

Hagia Sophia is real estate registered on block/parcel number 57/7, located in the Cankurtaran quarter in Fatih District of Istanbul. Its ownership belongs to the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Fused Foundation, which also qualifies as a charity according to the Law on Foundations [29]. In addition to the Land Registry, the real estate is listed as number 139 in the VGM Central Istanbul Fused Charitable Foundation Real Estate Registers. In other words, the foundation, which qualifies as an immovable property charity, is an immovable property cultural asset. Figure 6 shows the foundation document (vakfiye) of Hagia Sophia dated 1462. The document in question is 65-m long and written on gazelle skin. In essence, the document establishes Fatih Sultan Mehmet’s own personal foundations. In addition to 12 mosques, the document includes the income and expenditure records of institutions such as hospitals and soup kitchens. The most important of these is undoubtedly Hagia Sophia and because of this, the document is referred to as the “Hagia Sophia Foundation” document (Figure 6). The document, which is kept in a private room in the archives of the General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre (TKGM), has been carefully preserved for five and a half centuries [43].

Figure 6.

Foundation document of Hagia Sophia [43].

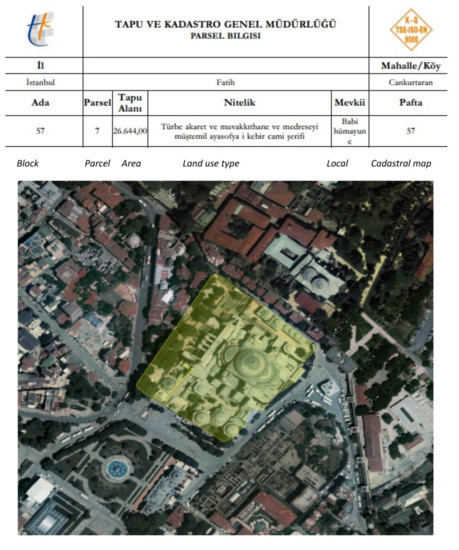

After 24 November 1934, when Hagia Sophia was converted into a museum, taking into account its foundation, it was registered in the cadastral proceedings on behalf of the Ebul Fetih Sultan Mehmet Foundation. The type of real estate was determined as the “Istanbul Grand Hagia Sophia Mosque, which included the tombs, rental property (akaret), the timing room (muvakkithane), and the madrasah”. Today, this classification of the property is still valid. The geometrical configuration of the plot where the property is located is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Screenshot of Hagia Sophia from the General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre (TKGM) [44].

According to the Turkish legal system, documented and undocumented real estate is determined via cadastral proceedings. The documents referred to are documents given or recognized by the public authority prior to cadastre. The most well-known of these are title deed registers and foundation documents because both of these document types are given only by authorized bodies of the State. The Hagia Sophia Foundation document, which was issued in the Ottoman period, is among the valid documents according to cadastral law and the Law on Foundations. This document is among the most basic rights documents to be used in cadastral proceedings. Its authenticity has been confirmed by TKGM and VGM records [22].

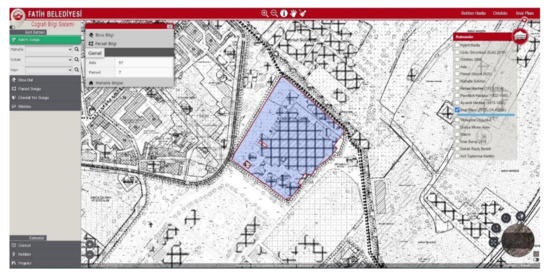

The zoning status of Hagia Sophia as shown in the image of Fatih Municipality via the WebGIS application is presented in Figure 8. A 1st Degree archaeological site, an urban-archaeological site, and a tourism area fall within the central boundaries of the zoning plan of Hagia Sophia/Ayasofya.

Figure 8.

Conservation zoning plan of Hagia Sophia [45].

4. Discussion

In line with the results obtained from the study, the 1934 administrative decision that transformed Hagia Sophia into a museum will be discussed here within the framework of foundation law and legal norms on cultural assets. In the Discussion section, precedent decisions taken in Turkey will also be assessed. The reasons that the Council of State revoked the 1934 decision turning Hagia Sophia into a museum will be analyzed.

4.1. Evaluation of Use of Hagia Sophia in Terms of Foundation Law

After the establishment of the State of the Republic of Turkey, the Law on Foundations first came into force in 1935, and then, in 2008, revealed how and in what form fused foundation real estate should be managed. According to the Law on Foundations, all the work and transactions of fused foundations are managed and represented by the VGM. Charity real properties are also used in line with their foundation documents. The use of this real estate outside the terms of their foundation is prohibited [29]. On the other hand, Article 30 of the Law on Foundations stipulates that, even if this type of qualified foundation immovable cultural asset is expropriated or sold, the ownership will be re-registered in the name of the foundation without payment [29,31].

Another monument of great importance similar to that of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul is the Hagia Sophia/Ayasofya Mosque in Trabzon Province [46] (see in Figure 9). According to the report of Coruhlu and Demir (2014), Trabzon Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque after Fatih Sultan Mehmet’s conquest of Trabzon in 1461 and was used as a mosque until the Russian occupation of 1916. It is understood from the document dated 23 Muharram 1318 H. (23 May 1900 CE), that the edifice was one of the ancient works converted from a church to a mosque after the conquest of Trabzon (BOA, EV.MKT-03030.00152). According to the documents dated 29 Muharram 1288 H. (20 April 1871 CE) and 25 Zilkade 1302 H. (5 September 1885 CE), it was determined that the wages of those working on the building were met from the income of the Trabzon Customs Muqâtaa (a kind of land whose income was directly transferred to the Ottoman treasury), the Yahya Pasha Foundation, and the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Han Foundation (VGM Register No:155/172/1372; BOA, EV-MKT-1314-82). The use of the building as a mosque was discontinued during the Russian occupation of 1916–1918, and then from 1918 to 1944 it was used as a mosque again. From 1944 to 1953 the building was used as a military depot and gas station. The building reverted to mosque status in 1953 and its restoration began in 1959 with a delegation from Edinburgh University together with the Foundation administration. Meanwhile, a section of the building continued to function as a mosque. The repairs were completed in 1961, and after the restoration, the frescoes in the building were uncovered and the use of the edifice as a mosque was stopped. Without the permission or approval of the VGM, it was used as a museum, first under the Ministry of Education and then under the Ministry of Culture. The lawsuit that was filed by the VGM in 1978, with the claim that the work should be used in accordance with the terms of the foundation, was finalized in 2013. At the end of the trial, as a result of the court order, the building began to serve again in accordance with its function as a mosque. As can be seen, the property rights of both monumental works, in Istanbul and in Trabzon, have similar characteristics in terms of restrictions on their usage [47].

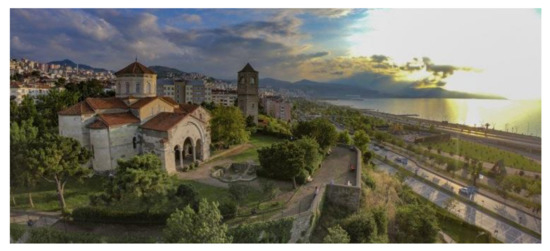

Figure 9.

Trabzon Hagia Sophia [46].

4.2. Property Right of Hagia Sophia in Light of European Legal Norms

The right to property defined in Article 1, Protocol No.1 of the ECHR has proven to be one of the most controversial and persistently disputed rights within the Convention [48]. In a claim of violation of property rights, the European legal system first examines whether a property right (of property and goods) exists, then whether an interference with the property has taken place, and finally, whether the interference was lawful. If the court finds that the interference is not legitimate, it can rule that the right to property has been violated [15,16,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56].

In terms of property rights, the base document of Hagia Sophia is Fatih Sultan Mehmet’s Hagia Sophia foundation document. This document is a legal document and is still valid in Turkey. As a matter of fact, there is no discussion in the country about the ownership of the monument. However, due to its use as the museum, the right to use and enjoy the right of ownership is obstructed. In terms of the owner’s benefits, the active and protective powers provided by the property right have been disabled. Based on this interference, the Council of Ministers decree contradicts the Law on Foundations.

4.3. Usage of Hagia Sophia within the Framework of the Law on Conservation of Cultural and Natural Assets

In Turkey, the conservation of cultural and natural assets is carried out within the framework of the Cultural and Natural Assets Conservation Act [37]. The High Council for Conservation and Regional Conservation Councils established under the law regulate activities regarding cultural assets. However, some cultural assets and sites under the jurisdiction of these councils, as with Hagia Sophia, are related to foundations in terms of property rights.

The Council has the authority to evaluate plans and projects regarding the conservation and use of a monument in accordance with its original character. The Council is not authorized to give the monument a function that restricts the right to property because a situation such as the restriction of the right to property will emerge. This situation evokes the concept of legal confiscation without expropriation [26].

Article 10 of the Law on Conservation of Cultural and Natural Assets authorizes the VGM, following a decision of the Conservation Councils, to protect and evaluate the cultural and natural assets of the fused foundations under its administration and control. Article 11 of the same law states that the owner can exercise all the authority entailed by the property rights not contrary to the provisions of this law. In accordance with Article 15—paragraph a/2, the Conservation Council has the authority to determine the function only from the point of expropriation and confiscation of the monument.

The Law on Conservation of Cultural and Natural Assets points out that the VGM will evaluate the cultural relevance of an existing work without harming its character or the historical and architectural objects it contains, provided that it is suitable for projects such as survey, restoration, and renovation work. It is clear that the Law has not granted the Council the authority, as in Article 15—paragraph a/2, to determine the function of the cultural assets owned by the fused foundations under the management and representation of the VGM.

4.4. Transformation of Foundation Cultural Real Estate into Another Property

According to the Law on Foundations, foundation cultural assets that were formed by a foundation, but which have been acquired by the treasury, municipality, private administrations, or village legal entities by any means (expropriation, land readjustment, etc.) are to be transferred to the fused foundation [29]. In such cases, the ownership of the cultural real estate can be re-registered free of charge in the name of the foundation to which it belongs [31]. In particular, when addressing the subject of Hagia Sophia as the real estate of a fused charitable foundation, according to the Law on Foundations, it is not possible to change the existing ownership rights of the monument by expropriating it.

4.5. The Decision of the Council of State Canceling the Decision of the Council of Ministers Transforming Hagia Sophia into a Museum

During the review phase of this article about the usage of Hagia Sophia, the Council of State took a new decision on 2 July 2020 on the case that had been filed to restore its mosque function [57]. This decision annulled the 1934 decree of the Council of Ministers that envisaged the use of Hagia Sophia as a museum. The reasons put forward in this article overlap significantly with the decision of the Council of State.

The case was filed by an organization established to preserve foundations and to support historical monuments and the environment. The defendant was the Presidency. In summary, the plaintiff claimed that Hagia Sophia was a mosque and not a museum in the deed document and that the work should be used as a mosque in accordance with this foundation document. The defendant, on the other hand, claimed that the Council of Ministers was authorized in the case of such dispositions, provided that they are not contrary to the Constitution or the law, and that the change in the use of Hagia Sophia is at the disposal of the executive. The main justifications for the decision are given in the following paragraphs.

In the decision of the Council of State, it was emphasized that foundations are groups of property formed by the specification of properties belonging to real/legal persons according to the Turkish Civil Code. It was stated that when making a decision about foundations, their foundation documents should be examined carefully. Subsequently, referring to the Law on Foundations, it was stated that the charitable real estate belonging to defunct foundations should be given priority by the VGM in line with their foundation documents.

The Council of State also gave the case of the Kariye Mosque as a precedent in its decision regarding Hagia Sophia. The Kariye Mosque, just like Hagia Sophia, is one of the charity immovable properties belonging to the fused Fatih Sultan Mehmet Foundation, which was dedicated according to private law provisions during the period of the Ottoman Empire. The decision that turned the work into a museum during the Republican era was cancelled by the Council of State in 2017. In this decision it is stated that, “The main feature of charity foundations is that they are protected against third parties as well as the State itself against misuse. The fact that these foundations are under the protection of the State does not mean that the State can dispose of foundation properties at any time and as it wishes. For this reason, it is against the law to assign charitable foundations to any other purpose” [58].

In the decision of the Council of State, the property and rights of foundations, as a group of properties and legal entities subject to private law, and the protection of the existence of their legal status are under the guarantee of the Constitution’s regulations on freedom of ownership and organization. Therefore, in the event that the purpose of the foundation or its properties is changed by going beyond the founding will put forward by the foundations, the private law status of the foundation will be compromised.

In the decision of the Council of State, it was stated that as a result of the protected status of foundations (including those established in the Ottoman period), their real estate and rights were guaranteed by the ECHR within the scope of property right, and precedent decisions were presented. Accordingly, it was alleged that changing the qualification of the foundation immovable (real) properties contrary to the will of the foundation was incompatible with the ECtHR case law.

Determination of the use of Hagia Sophia was evaluated in terms of international law, within the framework of “foundation property law” in domestic law. Accordingly, it is obligatory to abide by the principles of “fully respecting sovereignty” and “not harming property rights provided by national laws” expressed in the sixth article of the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage.

As can be understood from the reasons given above, when the Council of State annulled the museum decision taken by the administration in 1935, it took into account the legal norms stemming from domestic law. In summary, the decision demonstrates that the Ottoman foundations are recognized by positive law and that the founding will of the foundations should be protected, their legal status should be secured, and their property rights should not be harmed, etc.

According to the current situation, the management of Hagia Sophia has been transferred back to the VGM. Consequently, all types of projects (maintenance, restoration, etc.) regarding the property are to be carried out by this institution and it is operated as a mosque under the Directorate of Religious Affairs.

5. Conclusions

The change in the usage of the Hagia Sophia and its legal status is summarized in this section. The edifice was used as a church between 360 and 1453. In 1453, Fatih Sultan Mehmet conquered Istanbul and subsequently, in 1462, of his own volition established a foundation. He dedicated Hagia Sophia to this foundation with the condition that it be used as a mosque. The monument was used as a mosque until 1934, when it was converted into a museum with the Council of Ministers decree. As a result of the cadastral work carried out in 1935, the monument was recorded as a mosque in the Land Registry. At the same time, the monument was also registered in the Foundation Immovable Property Registry of the VGM as real estate of a charitable mosque foundation. The ownership of the monument still belongs to the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Fused Foundation. Under the Law on Foundations, the VGM is responsible for the management of fused foundations.

According to the Law on Foundations, the use of charitable foundation immovable properties outside the terms of the foundation is completely prohibited. If the foundation does not have the opportunity to use it in accordance with its purpose or if this purpose is against the law or public order, or if it loses its eligibility, it can be turned over to a similar charity or one closest to it by the decision of the Foundations Council. Accordingly, even upon the dissolution of the conditions of the foundation, the use of the relevant real estate for the same or the closest purpose was made compulsory.

It is acknowledged that the right to property consists of bare ownership (rakabe) and the right to use and benefit from it. The decision that turned the monument into a museum restricted the right to property of the foundation. In other words, this decision interfered with the right to use and benefit from the monument, whose bare ownership still belongs to the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Fused Foundation. The right to use and enjoy is among the limited rights recorded in the Land Registry in favor of another person or real property, at the will of the owner of the property. With the VGM recorded in the Land Registry as representing the property owner for Hagia Sophia, no such limited real right exists. The use of the property as a museum prevents the right of the foundation, as the owner, to use and benefit from it. Thus, it interferes with these rights of the foundation.

The monument is registered as a cultural asset and remains a protected site as per the Law on Conservation of Cultural and Natural Assets. Therefore, the relevant Regional Council for Conservation of Cultural and Natural Assets has some powers over the protected monument. These powers aim to protect the monument and transfer it to future generations. In this context, the Council must ensure that technical operations carried out such as survey, restoration, and renovation projects are in a sustainable protection–use–conservation balance. Apart from this, the Conservation Council does not have the authority to decide on the usage function of the monument. The law also states that the use of such monuments by the owner as a prerequisite of the property right will continue as long as the cultural/natural asset does not deteriorate. This law also points to the VGM as the institution to authorize the function for which the monument will be used.

It is clear that Turkey will protect Hagia Sophia thereafter in line with UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, just as it protected it in the past. However, in the aforementioned contract, there is no obstacle to the determination of the use of Hagia Sophia according to domestic law, provided that the work is protected and well-maintained.

When the subject is examined within the framework of international law, attention is drawn to the decisions of the European legal system on property. Turkey has recognized the right of individual petition to the ECtHR. In addition, with Article 90 of the Turkish Constitution, the ECtHR decisions are binding in terms of the Turkish judiciary, and must be strictly observed and followed. For these decisions in a case, firstly, the existence of the right to property is investigated, then the occurrence of a violation is examined, and finally, the legality of the interference is established. With the Land Registry and the Foundation Registry, the existence of the private property right to Hagia Sophia is evident. Although there are no registered limited real rights restricting this property, it is clear that the Council of Ministers decree, as an administrative decision, violated the exercising of the right to use and benefit from the property. It is clear that this violation did not comply with the legislation in which property rights are defined or with equivalent court decisions.

It is no surprise that the 1934 decision of the Council of Ministers, which envisaged the use of Hagia Sophia as a museum, was annulled by the Council of State in 2020, due to the reasons listed above. The reason for the decision is derived from domestic law. Indeed, despite their cultural assets, there are many works that still function as mosques. Among them are the Sultan Ahmet Mosque, known as the Blue Mosque, the Süleymaniye Mosque, and the Şehzade Mehmet Mosque, all located in Istanbul. Just as in these works, the cultural property feature of Hagia Sophia will be preserved in accordance with international conventions. By their nature, such works are already museums. They are the common heritage of humanity and their doors are open to humanity. The performance of daily prayers will not prevent Hagia Sophia from maintaining its cultural existence as a museum. In this respect, while continuing this mission as the common heritage of humanity, the work will continue to function as a mosque in accordance with the use stipulated by domestic law.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.E.C, B.U.; Methodology, Y.E.C., B.U. and O.Y.; Resources, Y.E.C., B.U. and O.Y; Investigation, Y.E.C., B.U. and O.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.E.C. and O.Y.; Writing—review and editing, Y.E.C., B.U. and O.Y; Validation, Y.E.C., B.U. and O.Y; visualization, Y.E.C. and O.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank TKGM and VGM for their provide documents (land registry, foundation charter and foundational information) to the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Doğrul, Ö.R. Anatolia, Central Asia and Timur; Translated from Ruy Gonzales d Clavijo; Ses Yayınlar: Istanbul, Turkey, 1993; p. s.45. [Google Scholar]

- Armağan, M. Hagia Sophia Intrigues; Kapı Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2017; p. 312. ISBN 6055147969. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Çift, P.; Altunay, E. The Secret History of Istanbul Hagia Sophia; Destek Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2017; ISBN 978-605-311-070-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hagia Sophia Kebir Mosque—Istanbul. 2020. Available online: https://www.kulturportali.gov.tr/turkiye/istanbul/gezilecekyer/ayasofya-muzesi (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Aykaç, P. Contesting the Byzantine Past: Four Hagia Sophias as Ideological Battlegrounds of Architectural Conservation in Turkey. Herit. Soc. 2018, 11, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, A. Sadece İslam Hukuku değil Evrensel Hukuk’ta Cami Olarak Kullanılmasını Gerektirir. J. Derin Tar. 2020, 101, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Akgunduz, A.; Ozturk, S.; Baş, Y. A Temple in Three Periods Hagia Sophia; Osmanlı Araştırmaları Vakfı: Istanbul, Turkey, 2005; p. 893. ISBN 978-975-7268-35-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kızıltoprak, S. Ayasofya Kararı Milli Egemenlik ve Bağımsızlık İradesinin İlanıdır. J. Derin Tar. 2020, 101, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Coruhlu, Y.E.; Demir, O.; Yıldız, O. Puzzle of the Hagia Sophia: Church, Mosque, Museum, Which One? J. Turk. Justice Acad. 2016, 7, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Old Photographs of Hagia Sophia (23 Pieces). 2020. Available online: https://tarihkurdu.net/ayasofyanin-eski-fotograflari.html (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Coruhlu, Y.E.; Er Nas, S.; Uzun, B.; Yildiz, O.; Şahin, F. Determination of the Misconception in the Relation between Foundation and Ownership on the Students of Geomatics Engineerıng; Project Final Report, supported by Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (No: 117Y261); TÜBİTAK: Ankara, Turkey, 2020.

- UDHR; Universal Declaration of Human Rights. All Human Rights for All, Fiftieth Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948–1998). 1948. Available online: http://www.un.org (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- ECHR (Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms). Registry of the European Court of Human Rights, Rome. 1950. Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Şimşek, S. Positive Obligations of States in terms of Protection of the Right of Property in accordance withe the Judgement of the Europen Court of Human Rights. Sayıştay Derg. 2012, 84, s.3. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case “Relatıng to Certaın Aspects of the Laws on the Use of Languages in Educatıon in Belgıum” v. Belgıum (Merits); Application Nos. 1474/62;1677/62; 1691/62; 1769/63; 1994/63; 2126/64.23.07.1968; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Öneryıldız v. Turkey; Application No. 48939/99; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Birben, Ü.; Güneş, Y. Ownership Perception and Land Ownership in the Ottoman Period. Kazancı Hukuk Araştırmaları Derg. 2014, 2, 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Karadağ, H.; Şit, M. The Ottoman State Evaluatıon of Land Ownership for Economic Systems. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan Üniversitesi Sos. Bilimler Derg. 2016, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cin, H. Ottoman Land Ownership and Its Disruption, 2nd ed.; Ministry of Culture Publishing: Istanbul, Turkey, 1985. (In Turkish)

- Yazıcı, A. The Ottoman Land Code (1274/1858) and Comparison between Islamic Inheritance Law and Land Transfer Regulations. EKEV Akad. Derg. 2014, 18, 449–470. [Google Scholar]

- Aydoğdu, M. The Concept of Medieval Feudal Ownershıp and Influences of the Land System in Ottoman Law on the Transfer and Allocatıon of Agrıcultural Enterprıses to Heirs. Dokuz Eylul Univ. Hukuk Fakültesi Derg. 2016, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, O.; Coruhlu, Y.E. Determining the Property Ownership on Cadastral Works in Turkey. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, O.; Coruhlu, Y.E.; Demir, O. A Visional Overview to Renovation Concept on Cadastral Works in Turkey. Sigma J. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2015, 33, 503–519. [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete). Turkish Constitution, 17863 Duplication Press; Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete): Ankara, Turkey, 1982.

- Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete). Turkish Civil Code, 24607; Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete): Ankara, Turkey, 2001.

- Coruhlu, Y.E.; Uzun, B.; Yildiz, O. Zoning plan-based legal confiscation without expropriation in Turkey in light of ECHR decisions. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbant, A. European Court of Human Rights and Constitutional Individual Application, Constitutional Jurisdiction. J. Anayasa Yargısı 2015, 32, 423–442. [Google Scholar]

- VGM; Directorate General of Foundations. Projection of a Civilization Foundations; Directorate General of Foundations Publications: Istanbul, Turkey, 2012; p. 101. ISBN 978-975-19-5292-9.

- Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete). Law on Foundations, 26800; Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete): Ankara, Turkey, 2008.

- Coruhlu, Y.E. Management Problems and Solutıon Approaches on Protection and Development of Foundation Properties. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Natural Science, Karadeniz Technical University, Trabzon, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coruhlu, Y.E. Registration of foundation properties–cultural asset on behalf of their own fused foundations. Surv. Rev. 2016, 48, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Coruhlu, Y.E.; Demir, O. Institutional and Occupational Development of Foundations (GDF) and its Experts on Land Market: A Case Study in Turkey. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2015, 24, 695–706. [Google Scholar]

- Turkey General Statistics for the Protection of Immovable Cultural Property. 2020. Available online: http://www.kulturvarliklari.gov.tr/TR-44798/turkiye-geneli-korunmasi-gerekli-tasinmaz-kultur-varlig-.html (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete). Zoning Law, 18749; Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete): Ankara, Turkey, 1985.

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 2020. Available online: https://muze.gov.tr/muze-detay?SectionId=AYS01&DistId=AYS (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete). Participation of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage Convention on the Protection of the Republic of Turkey on Assent to Laws, 17670; Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete): Ankara, Turkey, 1982.

- Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete). Law on Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage, 18113; Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete): Ankara, Turkey, 1983.

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Brumarescu v. Romania; Application No. 28342/95; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Vontas and Others v. Greece; Application No. 43588/06; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Bozcaada Kimisis Teodoku Rum Ortodoks Kilisesi Vakfı (Greek Orthodox Church Foundation) v. Turkey; Application No. 37646/03; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Fener Rum Erkek Lisesi Vakfı (Fener Greek Boys’ Secondary School Foundation) v. Turkey; Application No. 34478/97; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Fener Rum Patrikliği (Fener Greek Patrıarchy) v. Turkey; Application No. 14340/05; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- TKGM Official Website. 2020. Available online: https://www.tkgm.gov.tr/tr/icerik/fatih-sultan-mehmetin-ayasofya-vakfiyesi-tapuya-emanet (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre Parcel Inquiry Application. 2020. Available online: http://parselsorgu.tkgm.gov.tr/ (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- The Map of Fatih Municipality. 2020. Available online: https://gis.fatih.bel.tr/webgis/ (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Hagia Sophia Museum (with Video). 2020. Available online: https://www.trabzon.net.tr/turizm/ayasofya-muzesi.html (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Coruhlu, Y.E.; Demir, O. An Investigation on “Property Right” of the Trabzon Ayasofya Mosque. Vakıflar Derg. 2014, 42, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D. Disputed Property Rights: Article 1 Protocol No. 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights and the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016. Eur. Law Rev. 2016, 41, 900–924. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Sporrong and Lönnroth v. Sweden; Application No. 7151/75; 7152/75; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Affaıre I.R.S. Et Autres C. Turquıe; Application No. 26338/95; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Bronıowskı v. Poland; Application No. 31443/96; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Jahn and Others v. Germany; Application Nos. 46720/99, 72203/01 and 72552/01; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Hakan Arı v. Turkey; Application No. 13331/07; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). Case of Ziya Çevik v. Turkey; Application No. 19145/08; ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights): Strasbourg, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yücel, Ö. De Facto Expropriation in Accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights; Justice Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2010; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sever, Ö. Jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights about de facto expropriation. J. Akad. Bakış 2012, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- State Council. The Court Decision Regarding the Annulment of the Administrative Decision that Turned Hagia Sophia into a Museum; Merits No: 2016/16015, Decision No: 2020/2595; State Council: Ankara, Turkey, 2020.

- Council of State. Plenary Session of the Chambers for Administrative Cases; Kariye Mosque Decision, Merits No: 2018/142, Decision No:2019/3130; Council of State: Ankara, Turkey, 2019.

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).