Land Deals, Wage Labour, and Everyday Politics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Capital Accumulation, Rural Class Differentiation and Adverse Incorporation

2.1. Every Day Politics

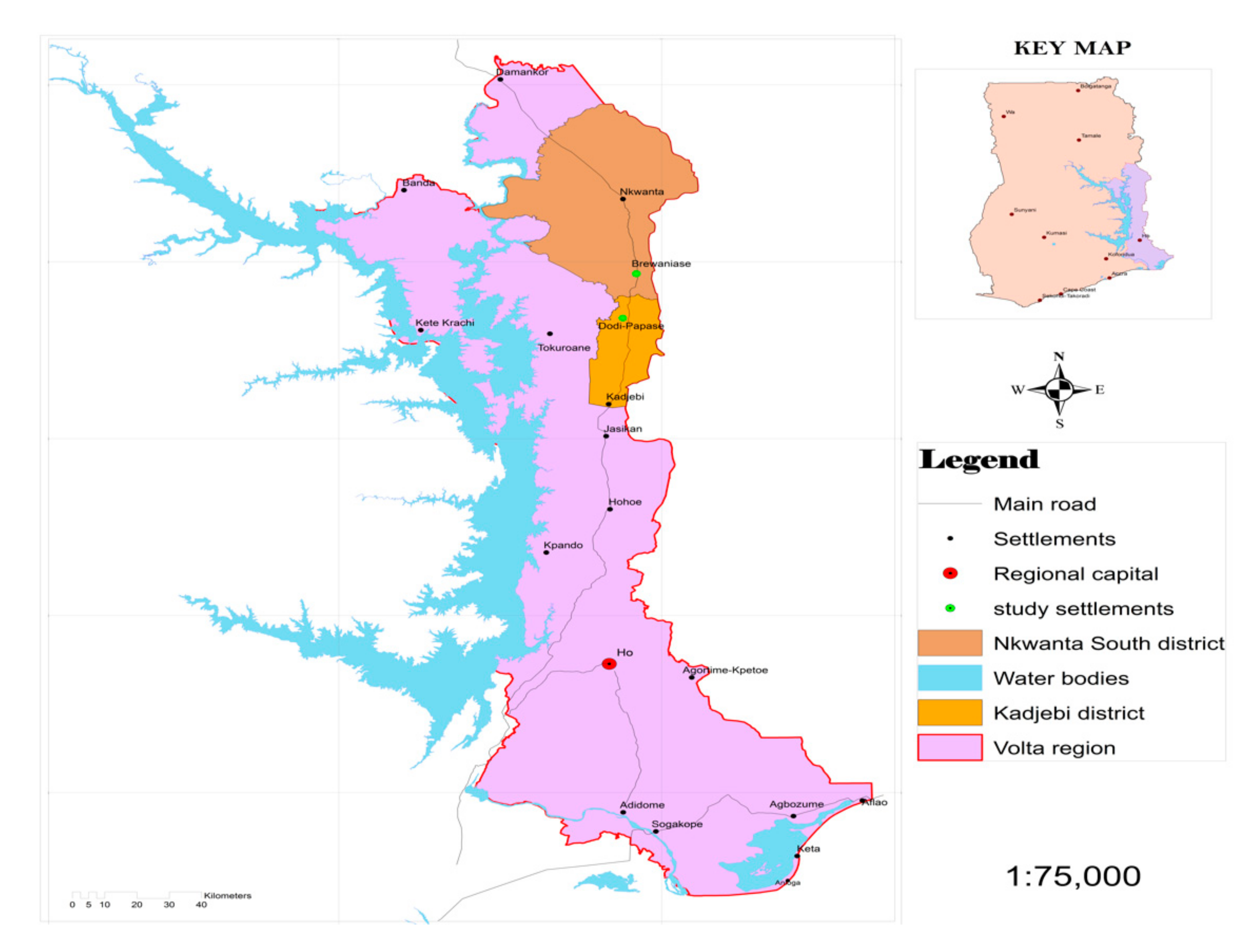

2.2. The Herakles-Volta Red Oil Palm Land Deal: Methods of Data Gathering and Analyses

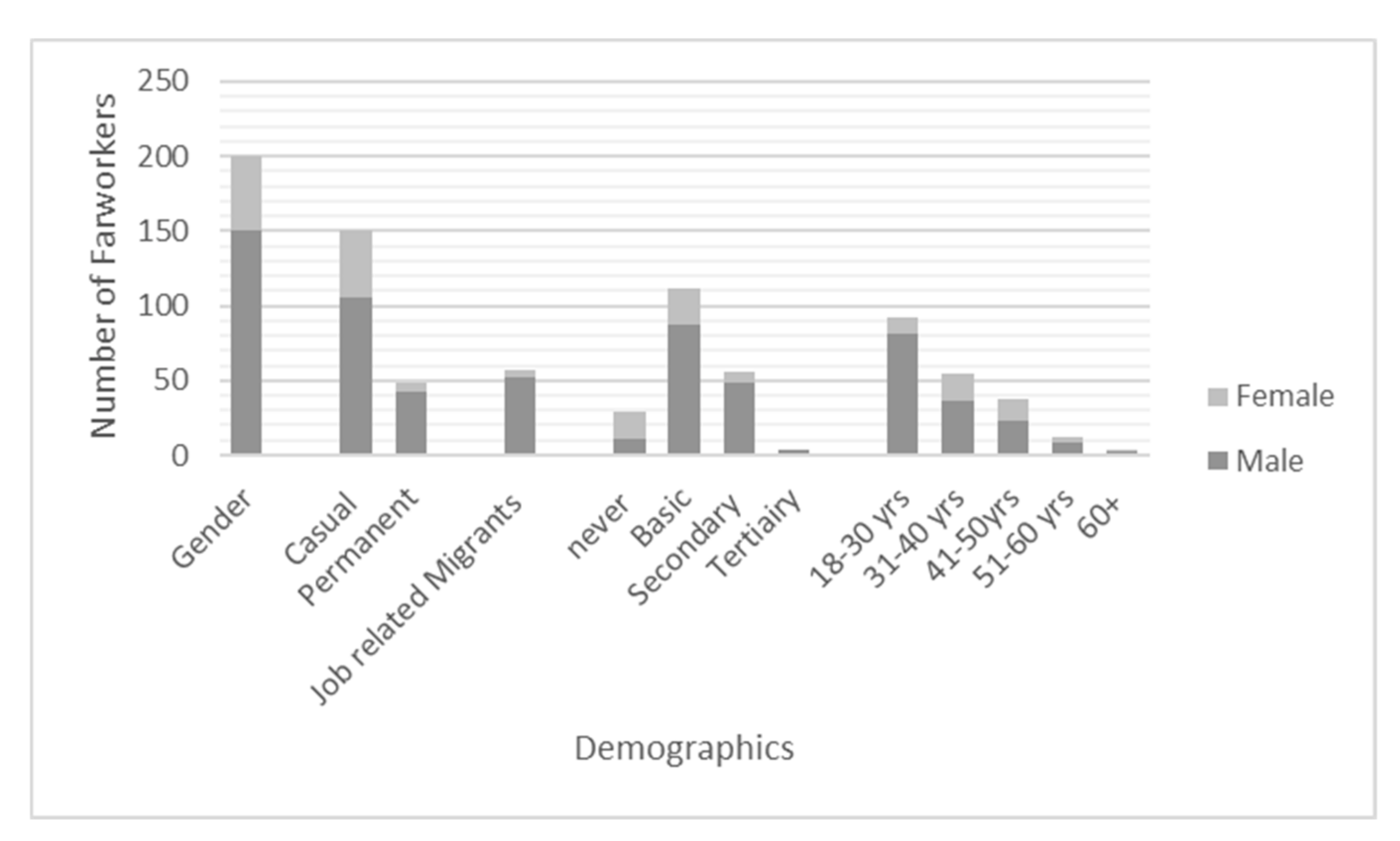

3. Class and Demographic Characteristics of Farmworkers

3.1. A Gendered Division of Labour

3.2. Adverse Incorporation: Precarious Labour and ‘Weakening’5 Bodies

‘My work is undefined. I am a casual worker, an operator and a driver. Sometimes they move me to join the oil palm processing mill workers, sometimes I transport firewood. If I am on the farm and there is a problem with the truck, my supervisors ask me to join the loading gang or do slashing’.

‘You see, this truck has no starter and no break. The steering wheel is poorly aligned and you can see that manifest in the front wheels. I have to start it in third gear and bring it to a halt in the fourth gear. Experience is the best teacher over here′.

‘they don’t pick us home on time, why won′t we have malaria? However, when you get malaria, they say that it is not a farm work-related disease, so you do not get a medical form’.

‘Every employee wants to see progress in their lives, but this is not the case on the plantation. The conditions are not good, and they sometimes do not respect our views because we are uneducated and casually employed. We worked hard on the plantation because we were sensitised about the positive effects on our communities, but if they could not cater for the he welfare of workers, how much more entire communities? For most of the people who remain farmworkers to date, they are there out of desperation′.

3.3. ‘We Have Become Surplus Labour’: Class Consciousness and Everyday Resistance

‘We have become surplus10 to them, if you die the job will continue’.

3.3.1. Deception, and Non-Compliance

‘We do not have hand gloves for pruning, so sometimes, I also do a shoddy work. My supervisors expect me to collect the branches and pack them at specified locations so that they do not hamper the work of slashers. Yet without gloves, I cannot work fast and I often finish work with injuries to my palm. So sometimes I do not collect the branches. They cannot monitor everyone, they cannot tell who did it, unfortunately, this affects the slashers too′.

‘if you work below your target and do nothing the rest of your time, they [supervisors] won’t say anything, but they won’t allow you to leave before 2:00 p.m. even in the off-peak seasons for harvesting. If you do so, you will not be marked’.

‘A worker will call to inform you of their inability to come to work because of ill health—when you know very well he is telling lies, but you can’t do anything about it. After the 20th12, you can confer that, in our attendance sheets, many people absent themselves to do ‘jobs′. Such attitudes affect us very much. For example, it reduces productivity especially when they do not inform us in time because of their anger’.

‘Sometimes when I’m sick of feverishness, I do not report that. I know the clinics in our communities do not have adequate capacity to detect all illness, so I complain of severe chest or neck pains which is directly related to harvesting. When I do that, I can get medical cover and also convince the medical officer to get me an excuse duty note for about 3 days, during this period I can rest, and also receive my daily wage’.

3.3.2. Acquiescence?

‘we are just hustling for them. I don’t want to becomean enemy so I have stopped complaining’.

Adwoa is a 51-year-old woman who has worked for nine years on the plantation. She is migrant, landless and has been divorced for seven years. She and her former husband had a lot of farm land in their hometown. They even had eight acres of oil palm and she intercropped vegetables. In the early 2000s when they heard of the PSI, they moved to a village in the Eastern Region to work at the nurseries. In the meantime, they left their crops in the hands of family members and that did not work out well. At the same time, her husband had refused to cater for their five daughters under the perception that girls will not bring any wealth to him in future, but rather to their husbands: a reason for their divorce. She has been working all these years to take care of the children’s education. Although she has been a permanent worker upon recruitment, she complains ‘the work is tedious, but if you are not educated do not have any other tradeable skill, what do you do? ‘Now I can see that I’m tired and very weakened’ but what can I do’? She does not envision working until pension, but her goal is to clear the educational costs, and then move to capital city to stay with her children, and perhaps start a trade. Now, she comports herself to safeguard her employment and permanent contract status.

3.3.3. Absenteeism: Production and Action

‘I have just acquired a piece of land from my landlord (residential) to plant corn and cassava. My friends have been teasing me and I also realised that I can’t be buying food all the time. They have agreed to support me with their labour to start the farm this year so that I don’t waste my money on food′.

‘Getting people to work on the farm is difficult. They have to search for a new person, train him or her and hope that he or she stays on. What I can do in 30 min on this farm. A new entrant might use over 2 hours and this will affect the company’.

4. Discussion

4.1. Contextualising the Farmworkers’ Politics

‘We have attempted a strike before. It landed the headmen in trouble because some workers informed management that the leaders spearheaded it. They [the headmen] were rebuked for that’.

4.2. Everyday Politics as Weapons of the Weak?

‘People have been working with us for a very long time, but their attitude towards work is bad. At the time that we need workers for our work, that is when they have left the job to go to their own farms. Sometimes it takes two to three months, especially when it is corn season. Imagine if you engage such a person a permanent worker. Sometimes when you make them permanent, their mentalities change and then you realize that the casual workers even work harder’.

‘I cultivate yam, groundnuts and cassava and corn. I have always wanted to add ginger but it is time consuming, and the regulations at work place won’t allow me to do so. Corn can never have a better price than ginger’.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amanor, K.S. Global Resource Grabs, Agribusiness Concentration and the Smallholder: Two West African Case Studies. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, P. The Land Grab and Corporate Food Regime Restructuring. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, M.; McKeon, N.; Borras, S. Land Grabbing and Global Governance: Critical Perspectives. Globalizations 2013, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation? An Introduction to Land Grabbing and Political Reactions ‘from Below.’ . J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 467–488. [Google Scholar]

- Mamonova, N. Resistance or Adaptation? Ukrainian Peasants’ Responses to Large-Scale Land Acquisitions. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 607–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larder, N. Space for Pluralism? Examining the Malibya Land Grab. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniello, G. Social Struggles in Uganda’s Acholiland: Understanding Responses and Resistance to Amuru Sugar Works. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulle, E. Social Differentiation and the Politics of Land: Sugar Cane Outgrowing in Kilombero, Tanzania. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2016, 43, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte, M.J. La Vía Campesina, Brazilian Peasants, and the Agribusiness Model of Agriculture: Towards an Alternative Model of Agrarian Democratic Governance. Stud. Polit. Econ. 2010, 85, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.A.; Sauer, S. Rural Unions and the Struggle for Land in Brazil. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 1109–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K. Global Restructuring and Land Rights in Ghana: Forest Food Chains, Timber, and Rural Livelihoods; Afrikainstitutet, Nordiska: Uppsala, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yaro, J.A.J.; Teye, J.K.J.; Torvikey, G.D. Agricultural Commercialisation Models, Agrarian Dynamics and Local Development in Ghana. J. Peasan. Stud. 2017, 44, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, F. How and Why Chiefs Formalise Land Use in Recent Times: The Politics of Land Dispossession through Biofuels Investments in Ghana. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2014, 41, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulmin, C.; Gueye, B. Transformation in West African Agricultures and the Role of Family Farms. Sahel West Africa Club (SWAC/OECD) SAH/D 2003, 241, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Lenin, V.I. The Development of Capitalism in Russia; Progress Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1964; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. Capital: Volume One. Karl Marx Sel. Writ. 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The New Imperialism; Oxford: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kautsky, K. The Agrarian Question; Swan: London, UK, 1899; Volumes I-II. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, H. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change; Fernwood Pub.: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lerche, J. From Rural Labour to Classes of Labour. In The Comparative Political Economy of Development; Harris-White, B., Heyer, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- White, B. Problems in the Empirical Analysis of Agrarian Differentiation. Agrarian Transformations: Local Processes and the State in Southeast Asia. G. Hart, A. Turton and B. White. Berkeley; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Oya, C. The Empirical Investigation of Rural Class Formation: Methodological Issues in a Study of Large- and Mid-Scale Farmers in Senegal. Hist. Mater. 2004, 12, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreda, T. Large-Scale Land Acquisitions, State Authority and Indigenous Local Communities: Insights from Ethiopia. Third World Q. 2016, 6597, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S. Shifting Burdens: Gender and Agrarian Change under Neoliberalism; Kumarian Press: Sterling, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman, J.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Quisumbing, A. The Gender Implications of Large-Scale Land Deals. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss-White, B. Inequality at Work in the Informal Economy: Key Issues and Illustrations. Int. Labour Rev. 2003, 142, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Corta, L.; Venkateshwarlu, D. Unfree Relations and the Feminisation of Agricultural Labour in Andhra Pradesh, 1970–95. J. Peasant Stud. 1999, 26, 71–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavoni, C.M. The Contested Terrain of Food Sovereignty Construction: Toward a Historical, Relational and Interactive Approach. J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 44, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD; FAO; IFAD; World Bank Group. Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment That Respects Rights, Livelihoods and Resources; A Discussion Note; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2008; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. Centering Labor in the Land Grab Debate. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, A.; Hickey, S. Adverse Incorporation, Social Exclusion, and Chronic Poverty. In Chronic Poverty; Rethinking International Development Series; Shepherd, A., Brunt, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, A. Adverse Incorporation and Agrarian Policy in South Africa. Or, How Not to Connect the Rural Poor to Growth; University of Western Cape: Cape Town, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K. Making Negotiated Land Reform Work: Initial Experience from Colombia, Brazil, and South Africa. World Dev. 1999, 27, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M. Can Small Farmers Survive, Prosper, or Be the Key Channel to Cut Mass Poverty? Electron. J. Agric. Dev. Econ. 2006, 3, 58–85. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, S. The Rational Peasant: The Political Economy of Rural Society in Vietnam; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Duggett, M. Marx on Peasants. J. Peasant Stud. 1975, 2, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenin, V.I. The Differentiation of the Peasantry. In Rural Development: Theories of Peasant Economy and Agrarian Change; John, H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1982; pp. 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Paige, J. A Theory of Rural Class Conflict. In Agrarian Revolution; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Thorner, D. Chayanov’s Concept of Peasant Economy. In The Theory of Peasant Economy; The American Economic Association: Homewood, IL, USA, 1966; pp. xi–xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Shanin, T. The Nature and Logic of the Peasant Economy—II: Diversity and Change: III. Policy and Intervention. J. Peasant Stud. 1974, 1, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Weapons of the Weak. In Every Day Forms of Peasant Resistance; Yale University Press: New Haven, CO, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D. Everyday Resistance or Routine Repression? Exaggeration as a Stratagem in Agrarian Conflict. J. Peasant Stud. 2001, 29, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, D. Oil Palm Industry Growth in Africa: A Value Chain and Smallholders’ Study for Ghana. In Rebuilding West Africa’s Food Potential; FAO/IFAD: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, G.B.; Rallis, S.F. Learning in the Field: An Introduction to Qualitative Research; SAGE: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A.; Tsikata, D. Policy Discourses on Women’s Land Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Implications of the Re-Turn to the Customary. J. Agrar. Chang. 2003, 3, 67–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S. Engendering the Political Economy of Agrarian Change. J. Peasant Stud. 2009, 36, 197–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Laughlin, B. Consuming Bodies: Health and Work in the Cane Fields in Xinavane, Mozambique. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2017, 43, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.; Peluso, N. A Theory of Access. Rural Sociol. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, K. Land and Labour: The Micro Politics of Land Grabbing in Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. The Peasantries of the Twenty-First Century: The Commoditisation Debate Revisited. J. Peasant Stud. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K. Family Values, Land Sales And Agricultural Commodification In South-Eastern Ghana. Afr. J. Int. Afr. Inst. 2010, 80, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ghana. The Labour Act; GoG Official Gazette: Accra, Ghana, 10th October 2003.

- Cramer, C.; Oya, C.; Sender, J. Lifting the Blinkers: A New View of Power, Diversity and Poverty in Mozambican Rural Labour Markets. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2008, 46, 361–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxemburg, R. The Accumulation of Capital.; Monthly; Monthly Review Press LCCN: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Gyapong, A.Y. Family Farms, Land Grabs and Agrarian Transformations: Some Silences in West African Food Sovereignty Discourses. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of the BRICS Initiative for Critical Agrarian Studies [New Extractivism, Peasantries and Social Dynamics: Critical Perspectives and Debates] Conference, Moscow, Russia, 13–16 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkvliet, B.J.T. Everyday Resistance to Injustice in a Philippine Village. J. Peasant Stud. 1986, 13, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | This number fluctuates due to the large number of casual workers. |

| 3 | Total valid respondents. |

| 4 | Referring to land purchased, not necessarily inherited or accessed through family. |

| 5 | A popular term used by the farmworkers especially women to describe the physical health as a result of intensity of labour. |

| 6 | The official numbers could be lower than the actual numbers because some have worked without contracts, such as the use of students in the past, occasional task sharing by family members, the carriers who work unofficially with harvesters, and others who are temporally hired when there is urgent need for workers- e.g., fire control. |

| 7 | Approx. 2.9 USD as of September 2018. |

| 8 | Most of them also do not have licences for operations because they trained on the farm and do not have the financial resources to apply for one. |

| 9 | As of January, 2019, after the company costs for two major truck accidents that occurred between August and December, 2019. |

| 10 | not translated-the original word used by the farmworker. |

| 11 | The names of respondents referenced in this paper have been replaced with pseudonyms. |

| 12 | The first working day of the month starts from 15th. |

| 13 | Remnants from farms of the dispossessed tenants and landowners, usually cassava. |

| 14 | Particularly, rural areas in the Western Region of Ghana, where they can maintain large cocoa farms under negotiated terms, and often with less control. Engaging in largescale cocoa production in their own communities is risky because the rampant bushfires in the dry seasons, and many of them claim that the best lands have been taken by the land deal. |

| 15 | Due to the geo-politics, much of the political and economic activities are centralised in the southern belt of the country where the capital and the biggest cities are located. |

| Instruments | Units of Analyses | Population | Number of Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Farmworkers | 237 | 200 |

| Qualitative Interviews; Life histories; stories; Conversations | Farmworkers | 237 | 80 |

| Supervisors | 8 | 7 | |

| Management and Administration | 6 | 6 | |

| Family Heads of Land Lords | 15 | 15 | |

| Traditional Authority | NA | 4 | |

| State Departments and Agencies | NA | 3 | |

| Focus Group Discussions | Women Farmworkers Harvesters Sprayers Former/workers who quit | NA | 4 |

| Observations | Farmworkers Work and Home Environments Everyday politics | NA | NA |

| 8 | Males | Females | Total Responses | Up to 1 Acre | 2–3 Acres | 4–5 Acres | 6–8 Acres | 9–10 Acres | 11–15 Acres |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm 1 | 134 | 42 | 176 | 44% | 42% | 9.6% | 2.8 | 1% | 0.6% |

| Farm 2 | 35 | 3 | 38 | 48.6% | 46% | 5.4% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Farm 3 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 40% | 40% | 20% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Farm Size (Acres) | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 acre | 42 | 35 | 77 |

| 2 | 44 | 5 | 49 |

| 3 | 25 | 0 | 25 |

| 4 | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| 5 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 8 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 10 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 11–15 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 134 | 42 | 1763 |

| Access | Male (%) | Female (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual4 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Family land | 31 | 10 | 41 |

| Tenancy (sharecropping) | 40.6 | 12.8 | 53.4 |

| Free Occupancy | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| Tasks | Gender | Target (Standard) | Target (Off-Peak and Poor Condition) | Lucrativeness of Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvesting | Men | 86 Bunches | 40–50 Bunches | High |

| Pruning | Men | 30–35 | 20–25 | Above Average |

| Loose Picking | Women | 4 bags | Daily Wage | Above Average |

| Round Weeding | Both | 30 Palms (2m around tree) | same | Average |

| Fertiliser Application | Women | 200 palms (1 kg of fertilizer per tree) | Same | Average |

| Slashing | Both | 9 m2 × 15 trees | Same | Low |

| Security | Men * | NA | NA |

|

| Technical Support | Men | Undefined | Undefined | |

| Operations | Men * | Undefined | Undefined | |

| Loading | Men | 2 Trips daily (for a team of 4–6 people) | Flexible | |

| Spraying | Men | 10 fillings (15l knapsack) | Same | |

| Irrigation | Men | Undefined | Undefined | |

| Carrying | Women | Per palm bunches harvested | (Laid-off by Harvesters) | Flat wage |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gyapong, A.Y. Land Deals, Wage Labour, and Everyday Politics. Land 2019, 8, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060094

Gyapong AY. Land Deals, Wage Labour, and Everyday Politics. Land. 2019; 8(6):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060094

Chicago/Turabian StyleGyapong, Adwoa Yeboah. 2019. "Land Deals, Wage Labour, and Everyday Politics" Land 8, no. 6: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060094

APA StyleGyapong, A. Y. (2019). Land Deals, Wage Labour, and Everyday Politics. Land, 8(6), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060094