Abstract

This article explores the question of political struggles for inclusion on an oil palm land deal in Ghana. It examines the employment dynamics and the everyday politics of rural wage workers on a transnational oil palm plantation which is located in a predominantly migrant and settler society where large-scale agricultural production has only been introduced within the past decade. It shows that, by the nature of labour organization, as well as other structural issues, workers do not benefit equally from their work on plantations. The main form of farmworkers’ political struggles in the studied case has been the ‘everyday forms of resistance’ against exploitation and for better terms of incorporation. Particularly, they express agency through acts such as absenteeism and non-compliance, as well as engaging in other productive activities which enable them to maintain their basic food sovereignty/security. Nonetheless, their multiple and individualized everyday politics are not necessarily changing the structure of social relations associated with capitalist agriculture. Overall, this paper contributes to the land grab literature by providing context specific dynamics of the impacts of, and politics around land deals, and how they are shaped by a multiplicity of factors-beyond class.

1. Introduction

It has been a decade since the global land rush caught the world’s attention through media, civil society, academic and policy engagement with the phenomenon. Debates have advanced towards a consensus on the multiplicity and convergence of issues: the global demand for food, energy and commodities, globalized transport and communication technologies, speculation, internal crises within capitalism, etc., all of which are crucial for the current neoliberal paradigm [1,2]. As ‘successful’ land deals are in different stages of implementation, the question of impact remains pertinent. Central to the debates on impacts has been how land deals influence the social relations of agrarian change, the political reactions from below, and the implications of these for development. In places where there is a strong presence of civil society organisations, especially social movements and development NGOs, campaigns to regulate in order to mitigate adverse impacts and maximize opportunities, or to stop and rollback land deals have not only gained wide popularity but also impacted the outcomes of various land deals [3] Nonetheless, recent studies have shown that it is not always the case that peasants oppose land grabs. As the impacts are differentiated for social groups and classes, so are the political reactions from below [4]. There have been accounts of adaptation and co-existence in post-soviet Russia [5], resistance and struggles for incorporation in Africa [6,7,8], and the overt resistance from workers, dispossessed farmers and indigenous communities in many parts of Southern America [9,10]. Certainly, the historical, political, economic and social contexts within which land grabs take place are vital to shaping the political reactions from below.

Ghana, for instance, has undergone about three major waves of large-scale agricultural commercialization since the late nineteenth century. Historically, Ghana′s (and many other West African Countries) agricultural production system has been fashioned around family farming and small-scale peasant practices aimed at simple reproduction [11]. While market exchanges have always existed even in pre-colonial periods, the extractive tendencies of colonial policies directed efforts to expand capital into rural areas through the introduction of export crop plantations and the development of commercial farming systems. Upon independence, the country had inherited an economy dependent on food crop exports, yet without the expected trickle-down benefits to the local people′s food security. As such, successive governments from the ‘socialist-developmentalist′ policy inclinations of the 1960s, to those informed by a liberal/neoliberal development paradigm which had influenced global political economy from the late 1970s till now, have sought to promote food self-sufficiency and rural development through a transformation of the existing production systems. Even though policies have not sought to replace completely the peasant system, over the years, they have approached small-scale schemes as that which need to be integrated into the ‘more efficient’ and ‘competitive’ value chains of commercial systems. Through the actions (e.g., market-led land policies) and inactions (e.g., poor implementation of labour regulations) of the state, an enabling environment is created for foreign and private investments in agribusinesses in the name of efficiency, productivity and employment [12]. These ideas also often resonate with the legitimating imperatives of traditional land institutions [13]. In addition, cash strapped rural folks who maintain both an economic and cultural attachment to land are often caught in a complex web of trade-offs. Under these contexts, in addition to the fact that there is not a strong base of rural social movements, land grabs are often received as a continuum between acquiescence and outright resistance.

When people affected by land grabs do not necessarily oppose their establishment, how do they perceive, experience and react to the terms of their incorporation into corporate farms? This study focuses on wage labourers on an oil palm plantation land deal in the Volta Region of Ghana, looking particularly into the employment dynamics-class and gendered access to the jobs available, exploitative working conditions, workers’ struggles for better terms of incorporation and the implications of their everyday political reactions for agrarian/ rural development. I employed a qualitative dominant mixed method for data collection. Combining methods is useful, not only to compare results, but also to integrate them in ways that provide a more comprehensive assessment of the issues under study. Guided by a gendered agrarian political economy approach, the paper shows the diverse and everyday ways in which wage workers navigate adverse working relations, but also cautions against romanticizing such unorganized efforts given that they are often associated with uncertain outcomes, difficult trade-offs, and its inability to change the structure of social relations, at least as shown in this case.

2. Capital Accumulation, Rural Class Differentiation and Adverse Incorporation

The African (Sub Saharan) agricultural system is characterized by family farms, small scale or peasant mode of production. Farming has been built on a resource base—land, seeds, livestock, fisheries, water, family labour, local knowledge and skills, social networks and traditions that were fundamentally uncommodified, and oriented towards survival and subsistence [11,14]. However, over the years, this mode production has been affected by the wider political economy which is reflected in the ways in which rural people′s access to land has been changing vis-à-vis their integration into the global economy. Although the ‘peasantry′ persists, it has also been evolving as a group that is differentiated in their social relations of production. Marxist political economy suggests that the penetration of capital into rural peasant societies is the main driving force for differentiation. The forceful appropriation of land and the expansion of commodity relations either through primitive accumulation or expanded reproduction [15,16,17] separate peasants from their means of production and create a polarizing rural economy. This is the starting point of differentiation and it is characterized by an accumulating class who control land and labour, and an exploited working class or proletariats divorced from their land and compelled to subsist through wage labour. Historically, this has been seen as an agrarian question of capital that ought to be resolved. This is a question of “whether, and how, capital is seizing hold of agriculture, revolutionizing it, making old forms of production and property untenable and creating the necessity for new ones” [18]. Byres interpreted the agrarian question as that which shows a continuous existence of obstacles to unleashing accumulation in the countryside and capitalist industrialization. Following Byres, and after years of researching this puzzle, Bernstein posits that the classic agrarian question was an ‘agrarian question of capital′ centred around three problematics: accumulation, production and politics. Capitalism thus blocks the possibility of achieving an egalitarian distribution of the material conditions of life, thereby placing rural agrarian societies into differentiated class relations. The classic agrarian question of capital also translates into an agrarian question of labour—one that is not confined to a single class of dispossessed proletariats but as a continuum to different classes of labour including semi proletariats who now depend directly and indirectly on the sale of their labour power for their own daily reproduction as well those who alternate between small wage work and small-scale petty commodity [19,20]. Premising a land grab study on the principle that class differentiation is manifested in uneven, concrete and context-specific forms of change provides a strong methodological foundation that highlights important specificities of affected rural classes.

Over the years, scholarship in agrarian political economy continues to highlight the complexities of the nature of capitalist development that may or not conform to these teleological patterns. In his study on the shortcomings of classic agrarian political economy theories of rural differentiation—mainly Marxists’ interpretations—White highlighted the need for dynamic and adaptable frameworks that approach social differentiation from a and relational viewpoint [21]. Similarly, Oya also notes that the application of class in the rural African context may even defy objectivity. For instance, a prominent basis of differentiation is ‘strangerhood’ rather than class [22]. Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, state policies of land distribution have made class a less significant, if not a non-existent means of differentiation [23]. To better understand rural agrarian structures and transformations in the era of a global land rush, other demographic and identity-related forms of differentiation (gender, age, ethnicity, religion, social status, etc.) is necessary. A gendered analysis of the implications of land deals on wage labour relations looks into the role of domestic relations of access to and control over resources and the structuring labour markets [24]. Here, the focus is not only about how domestic and formal institutions (dis)empower marginalised groups under different labour management schemes. However, class and identity relations revert backwards and forwards, suggesting the need to view class–gender analysis through a relational and an interactive lens [25,26,27,28].

As land grabs continue to take hold in many places, and in the light of recent debates around neoliberalism and the effects of capitalist expansion on poverty reduction, a major line of argument remains that there is a good potential of ‘win–win’ possibilities [29,30]. In the early days when land grab debates began to ‘grab’ research and policy attention, a central narrative that emerged among mainstream lines, but also along some critical views, was that exclusion (of the displaced and affected communities in general) is a major blockade to the poverty reducing potentials of agricultural investments [29]. For example, Tania Li argued that ‘unless vast numbers of jobs are created, or a global basic income grant is devised to redistribute the wealth generated in highly productive but labour-displacing ventures, any program that robs rural people of their foothold on the land must be firmly rejected’ [31]. Similarly, scholars in poverty studies use adverse or differential incorporation to critique oversimplified accounts of inclusion and exclusion in capitalist projects. Here, the question goes beyond the either/or of inclusion and exclusion to their complex interactions and their underlying conditions [32]. Within the framework of adverse incorporation and especially in relation to the labour question of this study, inclusion through wage labour is automatically perceived as an escape from poverty. Of course, mainstream approaches also recognise the challenges of inclusion and exclusion recommend good governance through regulations, standards and transparent institutions. These regulatory approaches, however, beg the question of underlying the social and political structures within which they emerge. As a framework for assessing the impacts of land deals, the multiple lenses of class, gender and adverse incorporation guide an exploration into the diverse ways in which particular rural classes, groups, and individuals are incorporated, not only into land investments, but also into the ‘larger social totalities—institutions, markets, political systems, social networks that drive differential consequences; and enable and/or constrain farmworkers’ politics [33].

2.1. Every Day Politics

Locating peasants’ political reactions within the context of contemporary global land grabs presents peasants’ politics on two broad fronts. One, is the struggles against eviction and dispossession in the defence of the commons. Indeed, this has been the most common assumption and underlying principles underlying anti-land grab advocacies and movements. The other is the class struggles of labour over terms of incorporation or against exploitation. Broadly, neoclassical/new institutional economics and agrarian political economy perspectives provide different theoretical explanations to peasants’ resistance under capitalism.

Neoclassical and new institutional economics conceptions are premised on the methodological assumption that peasants are rational and often make decisions upon calculating the benefits and risks of engaging in collective action [34,35]. According to Popkin [36], this explains why landless labourers may not necessarily act first although he describes them as the most politically conscious groups. He argued that, even when there are political reactions, it is usually based on incentives, and/or directed towards new opportunities which aim at taming markets and bureaucrats rather than restoring traditional systems.

Unlike mainstream accounts that place confidence in individual rationality and institutions, classic ideologies from agrarian political perspectives examine politics as a function of social structures. The two main strands of agrarian political economy—Marxist and moral economy perspectives show some variance in their approach to the explanation of peasant politics. Marxist political economy perspectives see politics from different viewpoints about class action, yet generally not very optimistic about the peasants’ ability to organise resistance due to the exploitative and controlling nature of dominant classes and state institutions, but also their lack of class consciousness [16,37,38]. Even when peasants exhibit consciousness, they often focus on economic bargaining rather than demanding radical political changes [39].

Moral economy perspectives, on the other hand, which, like Marxists’ interpretations, also follows the logic of differentiation and exploitation, perceive this, however, from a binary interpretation of class, whereby the policies and activities emanating from ruling elite classes threaten the subsistence of peasants (a single marginalised class) or that which unfavourably transforms their mode of (re) production [40,41]. Although peasants may be constrained to organise, their everyday ways of life express agency against the actions of ruling elites who threaten their means of subsistence. Their daily reactions of resistance, Scott referred to as ‘everyday politics’ [42]. Everyday politics involves little or no organisation to embrace, comply with, adjust, and contest norms and rules regarding authority over, production of, or allocation of resources. In his study on peasant resistance in southeast Asia, Scott described everyday politics as often unplanned, uncoordinated, and those involved ‘typically avoid any direct symbolic confrontation with authority or with elite norms’ [42]. It is usually low profile and private behaviour of the people and often entwined with individuals and small groups’ activities in their struggles to sustain their daily livelihoods while interacting with others like themselves, with superiors and with subordinates. Although some have critiqued the overestimation of the political significance of such everyday resistance [43], in contexts such as rural Ghana where political mobilizations against land deals rarely occur, everyday politics remain a useful way of understanding workers’ politics. An earlier study by Kojo Amanor on a post-independence state-led oil palm land grab in Ghana, [11] he revealed how some unemployed youth engaged in illicit night time harvesting of palm bunches even under tight security confrontations. Through other forms of everyday ‘action and production′, such as land occupation, squatting, divestment by contract farmers, marginalized groups express their dissatisfaction with unfavourable systems. Guided by the concept of everyday politics, the study explores the agency of different classes and groups of wageworkers in negotiating opportunities and risks associated with the conditions of their work. The study adopts a relational lens-linking the experiences and practices of people to the social, economic and political contexts within which they live [28].

2.2. The Herakles-Volta Red Oil Palm Land Deal: Methods of Data Gathering and Analyses

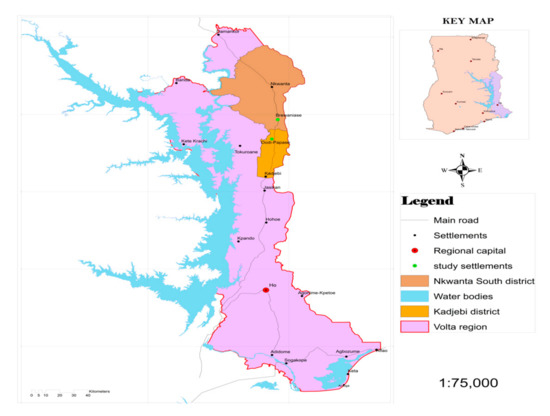

In the year 2002, the Government of Ghana, as part of a strategic rural development and industrialization plan, introduced the President’s Special Initiative on Oil Palm (PSI-Oil Palm). The primary goal of the project was to improve oil palm research and to develop nurseries for expanded production (to about 300,000 ha by 2007) using the private sector as the main wheel of development [44]. Although midway through the project collapsed, it contributed to an expansion in investor and farmer interests in the sector, not only through the establishment of estates but also in other related businesses along the oil palm value chain. The oil palm plantation in Brewaniase- a town in the Nkwanta Municipality- is one such investments that emerged within the context of the PSI. A 3750ha of land was acquired in 2008 by an American company, Sithe Global Sustainable Oils -an affiliate to Herakles Capital, New York1. Since 2013, the plantation has been managed under a new name- Volta Red, under the directorship of British Investors. Volta Red also has another 41 ha of oil palm plantation in Dodi Papase (Atta Kofi), and an oil palm processing mill at Ahamasu both of which are located in the neighbouring Kadjebi District within the Volta region of Ghana (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

The geographical scope of the study.

To set the context right in discussing the organization of labour and the politics of farmworkers, it is important to note that the new company as it stands now represents one that is struggling to operationalize its vision of production and processing—as a result of inherited lawsuits and outstanding rents, cost of changes in management and labour, and high costs of operating an off-site (about 25 km away) processing mill. Nonetheless, through management’s constant engagement with the workers, often in the form of paternalistic relations, the company is quietly surviving, but usually to the disadvantage of labour welfare and workers’ political reactions. Approximately, 2372 workers drawn from about five neighbouring communities are employed.

In the study, I adopted a qualitative predominant mixed methods of data collection and analyses. Fundamentally, the study was carried out qualitatively because it relies on probing, narratives, historical relations, and interactions that give relevant insight to explaining events and experiences of the affected people. In such instances, qualitative methods help to understand and analyse complex social phenomena and multiple “truths’ through contextual, emergent, and interpretive ways [45].

The results represent data collected during the peak and off-peak seasons between May 2018 and March 2019. I conducted semi-structured interviews with administrators of the plantation and other key stakeholders; made provisions for narratives and life history stories; and considered age, gender, ethnicity, duration of employment, contract, task, migrant status and access to land in my discussions with farmworkers. A total of 200 farmworkers, which also represents about 85 percent of the total workforce on the Brewaniase Plantation took part in a socio-economic survey. Living within the community, and having access to the plantation fields during the field work also gave me the opportunity to engage in both participant and non-participant observations. This allowed for a better understanding of what people do, mean, or believe as well as their experiences. Observation of workers during workhours and in their residences provided a first-hand appreciation of their diverse strategies, politics, and the construction of subjectivities and meanings.

See Table 1 for an overview of the methods employed.

Table 1.

A summary of data gathering methods.

3. Class and Demographic Characteristics of Farmworkers

A great majority of the farmworkers are semi-proletariats. From the survey, ninety-three percent (93%) of the 200 farmworkers who participated in the survey have access to farmlands in their communities or in neighbouring locations, while eighty-eight (88) percent are engaged in small scale farming with farm sizes ranging from one-tenth (0.1) of an acre to approximately fifteen (15) acres. Similar to the literature on intra-household gender inequalities [46,47], men tend to have access to multiple farms (up to three different farmlands) and bigger farm sizes than women Nonetheless, interviews conducted with most of the women suggest that their ability to cultivate and benefit from their own small plots of farmlands independent of their family/husbands’ lands. Table 2 provides a general overview of the farmland sizes (up to three different farm plots) among the farmworkers and Table 3 shows the gendered differences in land sizes (of the first plots mentioned).

Table 2.

Number and sizes of farmworkers.

Table 3.

Farm 1—Actual farm sizes by gender.

Being a settler society, sharecropping remains the most common form of land access (see Table 4). For the minority (7%) of workers who had no access to farmlands, the vast majority were urban-rural migrants who were either not interested in own farming, or were actively searching for a suitable land; and a few aging women who could not combine farming with their current jobs. Indeed, all but one of the farmworkers whose lands were affected had access to farmlands, yet with differentiated forms of ownership and use, often described to be less desirable. Labour on the plantation is therefore characterised by a complex mix of landed, less landed, sharecroppers, dispossessed proletariats and even some farmworkers (eight of them) who have their own sharecroppers. Although access to farmland is an important aspect of the people’s daily reproduction, the relative land availability means that the vast majority of the farmworkers are not driven into labour due to landlessness. Access to suitable farmlands, however, remain critical for the dispossessed proletariats who lost their entire family or share cropped lands. Many male adult farmworkers also depend on wages to invest and expand their own farms.

Table 4.

Farm 1—Form of Access to Farmlands.

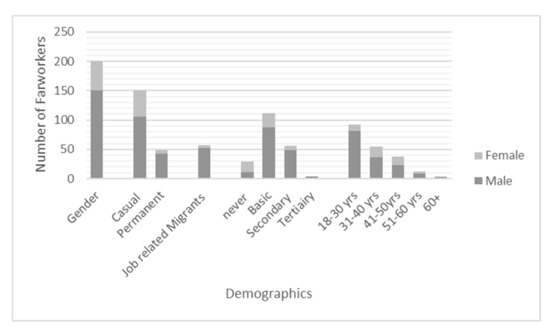

For many of the workers, education is an important reason for working on the plantation—the youth (males) who are temporarily out of school depend on wages to pursue higher education; and wage labour is the primary source of income for most women who are burdened with the responsibilities of their children’s educational needs. These results corroborate with the workers’ age distribution where approximately half of the male population falls between 18 and 30 years old, whereas, for women, it is about a fifth. The survey showed that sixty-six per cent of the women are between the ages of 31–50, and this is a child bearing and care giving period where rural women’s chances of education are very limited as compared to men, and especially if these women already missed basic education. Figure 2 below shows the population dynamics of the workers, particularly gender, age, employment contracts, and education.

Figure 2.

Demographic characteristics of Farmworkers. (Source: Author).

3.1. A Gendered Division of Labour

Labour on the plantation is divided by tasks carried out based on physical attribution, seasonality, and sometimes through discretionary decisions at the supervision level. The tasks are also gendered, with men having more opportunities to take up specific tasks. The core labourers engage in work that directly affect production: crop and soil maintenance, weed control and harvest-related activities These include pruning, slashing, round-weeding, spraying of weedicides, fertilizer application, irrigation; harvesting, and loose picking. They are deployed through the gang system often consisting of 25 workers. Tasks reserved for men include harvesting, pruning, spraying, fire control and loading (they load and transport the palm fruits to the processing site.) Slashing is done by both men and women, while loose-picking, which is a woman’s task, except occasionally when it becomes necessary for men to join. During peak season, harvesters employ their own workers to be head porters or what they call ‘carriers’ to transport the harvested palm bunches to specific locations on the farm. They often consist of women who could have social ties or not, with the harvesters. Another group of workers is the farm service workers, who are mostly skilled men engaged in technical operations. Their tasks that have close interaction between production and processing. They include mechanical engineers and fitters, carpenters, plumbers, vulcanizers, heavy-duty truck operators and drivers. The third group of workers are the support workers consisting mainly of security workers also supervise fire control in the dry seasons. There are no women represented in management, administration and supervision. Table 5 gives an overview of how labour is organised on the plantation.

Table 5.

Gender, tasks and targets.

3.2. Adverse Incorporation: Precarious Labour and ‘Weakening’5 Bodies

Job, income and health insecurity characterize the nature of work on the plantation. Compared to the initial phase of the oil palm establishment—when clearing, nursery and planting took place, employment opportunities have reduced considerably. The workers’ estimations put the figure at a 500-plus, and official records indicate that at least 392 people have previously worked, or are currently employed on the plantation6. With the exception of the 53 permanent workers (excluding eight supervisors), the rest (70% of the labour force), and nine out of every ten women, are casual workers with six-month renewable contracts or no contracts at all (see Figure 2). For casual workers, their job security window is opened only during the peak seasons (from April to August). Outside this period, especially between November and March, many of them are laid off, and their fates lie in the hopes of early rains and field conditions, their gender, and their relations with supervisors. Unlike reports from similar studies by Bridget O’ Laughlin, both casual and permanent workers benefit from a national social security/pension scheme [48]. Nonetheless, casual workers who seek progression to permanent contracts are usually the less landed, women, and those with limited alternative livelihoods, who want to benefit from job security, paid leave and particularly, access to loans, which are privileges preserved for only permanent workers. Interviews with the workers and management confirmed that, in the post 2013 transition to Volta Red, there has not been significant progression from casual to permanent contracts—a situation which the management justifies to be part of a cost cutting strategy and also dependent on worker’s commitment, a claim that many long-serving workers could not agree with. Not so different from mainstream optimism in the employment potentials of large-scale agricultural investments, the families and communities were under the illusions of massive job opportunities, with salaried, formal and permanent employment contracts.

Job insecurity is manifested not only in the employment contracts but also, in the rate and frequency of labour mobility and informality in production. In principle, recruited workers are to be employed in their preferred tasks, but that often depends on vacancy and their physical attributes. This is, however, particular to men, as they have much more flexibility and options to choose from the many male tasks. While workers often commence employment in their preferred tasks, their retention is characterized by mobility between tasks as determined by their supervisors. There are, however, some particular tasks such as spraying (weed control), where intake is largely by worker preference. The changes occur both within and outside related tasks, e.g., switches between harvesting and pruning, but also from machine operation to slashing. This practice is also the company’s way of managing the small numbers. For instance, a supervisor mentioned that they do not lay off most of the harvesters-they are rather moved to pruning because they are hard to come by and their task requires a lot of training. Whereas workers switching between the above tasks may still find it lucrative, for others, it affects their productivity and income. Women are highly affected when they are made to do slashing. In an informal conversation with one of the authorities, he emphasised that even though slashing is tedious, women are more respectful, truthful and follow instructions better than men. This is rather unfortunate because, even for those women who do their own farming, this is the one farm activity for which they regularly hire in labour or seek support. In addition, it also affects workers’ ability to organize around task-specific issues. One worker expressed:

‘My work is undefined. I am a casual worker, an operator and a driver. Sometimes they move me to join the oil palm processing mill workers, sometimes I transport firewood. If I am on the farm and there is a problem with the truck, my supervisors ask me to join the loading gang or do slashing’.

Second, with regard to wages, workers struggle with consistent delays, low income and wage differentiation. The remuneration scheme of the workers is premised on a time productivity-skill based piece rates system. The baseline daily wage of GH₵14.047 applies to work in the core labour and support service for both casual and permanent workers. It is used as the yardstick for calculating the piece rate or daily targets. This piece rate daily wage is about forty-five percent higher than the national minimum wage of GH₵9.68. The casual workers in the skilled service such as operators, receive a higher daily wage of GH₵19.5, while the remuneration of permanent skilled staff receive ranges between GH₵19.5 and GH₵25 cedes plus allowances. The harvesters who employ seasonal carriers have also been instructed by their supervisors not to pay them below the base wage daily wage—a situation which practically means that GH₵15 has become a flat wage even though these carriers are compelled to function alongside the productivity of their harvesters who can work seven times above their daily targets during peak seasons. Several factors influence the monthly income brackets of the workers. This includes gender, age, skill, experience, contract, engagement in other occupations, and the lucrativeness of tasks. Slashers, for instance, are often associated with the lowest incomes because it is not lucrative—their average monthly income ranges from GH₵200 to GH₵450 cedes as compared to harvester/pruners who indicated that their monthly incomes ranged between GH₵500 and GH₵1000. During peak seasons, harvesters could even earn a net income of over GH₵1500 per month (after paying their carriers). Women remain in the lowest income brackets, with a vast majority taking a monthly wage range between GH₵200 and GH₵350 below the expected monthly wage if they are regular. Other tasks in the core labour such spraying and irrigation are not accompanied with lucrative targets. Local perceptions around chemical spraying connotes a major health risk and therefore workers are not even interested in overworking for extra income. Workers in the support services and farm service labour, have relatively stable wages and are compensated with some bonuses. Compared to the conventional local farm labour rates, the plantation wages are far lower. For instance, sprayers earn half of their local rates, while slashers earn only a third of what they would have been paid for the same amount of work on small scale farms. However, they prefer to be on the plantation due to the relative availability of employment and income if compared to doing ‘by day′ small scale farm jobs. In effect, attractiveness to the plantation work is a result of some these constrained choices.

Third, there is a strong linkage between health and capital’s resort to casual labour- making it easy to evade the responsibility of protecting the occupational health of workers. All the workers are susceptible to various forms of injuries associated with poor field conditions and inadequate supply of protective clothing. Although they have regular access to boots, other supplies such as protective clothing and nose masks for sprayers, gloves for pruners and loose pickers, and rain coats are either under-supplied or of poor quality as the per workers′ expectations. Workers often raise these concerns at their weekly meetings with authorities, but the responses are rather persuasive, requiring them to be patient in waiting. Workers, especially those in the tasks of spraying, harvesting and pruning, are very much aware of the health implications of their work, and therefore seek some preferential treatment in accessing health services, e.g., the reinstitution of biannual health screenings.

Again, most the of drivers, truck and heavy equipment operators are not licensed to operate8,thus no insurance against accidents. Their financial struggles around not having access to licenses are further complicated on the one hand by their casual statuses, which deny them access to loans, and on the other hand, by the company′s unwillingness to commit to the responsibility of facilitating access to the license. For many of these operators, they believe that the company′s position is linked to the fear that they would go and seek better job opportunities elsewhere when they obtain their licenses—a situation that is very likely, according to the operators. In addition, they have to work with faulty machineries, which overtime, they have learned to adapt. Demonstrating this, a driver said:

‘You see, this truck has no starter and no break. The steering wheel is poorly aligned and you can see that manifest in the front wheels. I have to start it in third gear and bring it to a halt in the fourth gear. Experience is the best teacher over here′.

This puts not only them, but all workers who are also transported in these trucks, at risks of accidents and injuries. Per their work regulations, the company takes responsibility for any work-related health issues, especially for injuries and minor illness but other indirect and long-term health threats and sicknesses are often ignored or inadequately addressed. Even though almost seventy percent (70%) of the workers are already subscribed to the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), workers also want to caution against the extra costs that are sometimes associated with the NHIS scheme. During my second visit, 9 the rules had changed—having NHIS is a prerequisite for employment retention. It became almost like a chorus whenever I spoke to the workers, particularly women, about the intensity of their work— ‘adwuma yi, eweaken yen’ (we are weakened by this job). They looked frail and older than their ages, especially the pioneer workers who have worked for at least eight years and are still on casual contracts. Besides the tedious nature of the job, the distant location of the farm and their limited access to transport facilities put a heavy toll on their health. A woman farmworker complained:

‘they don’t pick us home on time, why won′t we have malaria? However, when you get malaria, they say that it is not a farm work-related disease, so you do not get a medical form’.

Closely linked are the stresses and pressure on women’s ability to deliver their household responsibilities. A normal routine for off-farm residents begins from 5:00 a.m. until about 5:00 p.m., although the productive hours are effectively eight hrs. Women have to start their day at least two hours earlier (by 3:30 a.m.), sometimes forced to wake and prepare their school going children. Their evening duties, including meals, also extend into the night. Even though the impacts depend largely on the household characteristics, in general, committed female workers do not get enough rest and end up being those within the lowest income brackets. The labour conditions on the plantation can be summed up below, by a former worker who said:

‘Every employee wants to see progress in their lives, but this is not the case on the plantation. The conditions are not good, and they sometimes do not respect our views because we are uneducated and casually employed. We worked hard on the plantation because we were sensitised about the positive effects on our communities, but if they could not cater for the he welfare of workers, how much more entire communities? For most of the people who remain farmworkers to date, they are there out of desperation′.

3.3. ‘We Have Become Surplus Labour’: Class Consciousness and Everyday Resistance

As a recap, in rural peasant economies such as that described above—characterised by exploitation and subordination—agrarian political theorists provide different explanations to the nature of political reactions that emerge i.e., revolt (radical and overt politics) and non-revolt, which are essentially linked to class relations, traditional community structures, or individual incentives [39,42]. Since 2008 when work started on the acquired land, the farm workers have not engaged significantly in overt politics to demand changes in unfavourable terms of incorporation. However, there is an increasing level of class consciousness among the workers, although sometimes contentious. A laid- off and dispossessed semi-proletariat, expressed,

‘We have become surplus10 to them, if you die the job will continue’.

Knowing this, how do they translate their claims and assertions into action against exploitation, and action for better terms of incorporation? Adopting some tenets of ethnography, particularly observations, informal conversations and interviews, I illustrate their everyday politics in dealing with the precarious nature of work on the plantation.

3.3.1. Deception, and Non-Compliance

During fieldwork, my Sundays were precious moments. This is the official resting day for permanent workers. Casual workers who worked on their farms on Saturdays also used took rest on Sundays, and of course with 89 percent of the workers being Christians, the hours between 1:00 p.m. and 6:00 pm was precious window of opportunity to talk to most of the workers who were then closed from church. It was one of these Sunday afternoons in July 2018 that I visited two relatives—Kofi and Kwame11—in their home at Brewaniase. They are displaced sharecroppers working on the plantation. Kwame is a permanent worker and has worked with the company since its establishment. Kofi, on the other hand, is a casual worker. After they lost their land, he worked on the plantation for a while and decided to travel to the city to work for years. In 2016, he returned so he could farm, and also help in catering for his aging and widowed father. He has since returned to the plantation working in pruning and harvesting. He described how risky it is, and what he does to ‘address it’,

‘We do not have hand gloves for pruning, so sometimes, I also do a shoddy work. My supervisors expect me to collect the branches and pack them at specified locations so that they do not hamper the work of slashers. Yet without gloves, I cannot work fast and I often finish work with injuries to my palm. So sometimes I do not collect the branches. They cannot monitor everyone, they cannot tell who did it, unfortunately, this affects the slashers too′.

Sprayers in particular are very conscious about the health implications of their tasks even though their claims are often premised on health hearsays. They capitalize on those perceived dangers and often break their working time rules by justifying the need to go home to wash off the chemicals. Like many other workers, Kofi also iterated the importance of his tasks within the entire production chain, thus his role in the functioning of the plantation. Per the way he values his position within the plantation system, he expected that he be allowed to work under favourable conditions, particularly, the flexibility to do a real piece rate i.e., get paid for what he can do in a day and not be forced to spend the whole day on the farm. In his words:

‘if you work below your target and do nothing the rest of your time, they [supervisors] won’t say anything, but they won’t allow you to leave before 2:00 p.m. even in the off-peak seasons for harvesting. If you do so, you will not be marked’.

He argued that his father had trained them in farming, and now the company is benefiting from it. Thus, he could not accept why they won’t allow them to work on their own farms. Sometimes, he secretly informs the headman or makes up a story that he is sick in order to avoid getting into trouble with authorities. Open deception is therefore very common among the workers and depending on their relations with superiors, and the occupational history of the superiors themselves—whether or not they have been in their shoes before. This is confirmed in the words of a headman who said:

‘A worker will call to inform you of their inability to come to work because of ill health—when you know very well he is telling lies, but you can’t do anything about it. After the 20th12, you can confer that, in our attendance sheets, many people absent themselves to do ‘jobs′. Such attitudes affect us very much. For example, it reduces productivity especially when they do not inform us in time because of their anger’.

For casual workers, not being entitled to annual paid leave meant they had to take their own breaks as and when necessary—sometimes they rest during the lay-off periods. Furthermore, the intensity of labour also breaks them down occasionally. However, not being able to justify requests for sick leave when they are not tangible work-related injuries leads to ‘new discoveries’ on ways and means around them. A young, literate and male farmworker narrated:

‘Sometimes when I’m sick of feverishness, I do not report that. I know the clinics in our communities do not have adequate capacity to detect all illness, so I complain of severe chest or neck pains which is directly related to harvesting. When I do that, I can get medical cover and also convince the medical officer to get me an excuse duty note for about 3 days, during this period I can rest, and also receive my daily wage’.

3.3.2. Acquiescence?

Structural differentiation plays a key role in shaping political reaction. Whereas in several land grab studies it is often assumed that dispossession, and class relations influence the political reactions of the people, in this study, the dynamics play out quite differently. Given that almost every farmworker has, or has a high likelihood of getting some (tenant) farmland, the question becomes more of access, in terms of the ability to benefit from land [49]. The location of land, its fertility, and access to inputs are important in determining the extent to which farm workers benefit from their land and consequently, the extent to which they depend on the income from the plantation work [39]. Going back to the data on the class positions of women, they are often the ones with narrow choices as many of them depend largely on the wage income. The situation is not so different for dispossessed proletariats, and migrants, especially urban-rural migrants, who may also be skilled, educated and not so interested in farming for extra income. As rightly argued by Kattono Ouma in her study of a rice field in Kenya, ‘there is great incentive for such workers to conform to the idea of a “subservient worker”, for the benefits that such repute may bring’ [50]. This is certainly not a case of false consciousness as one operator stated,

‘we are just hustling for them. I don’t want to becomean enemy so I have stopped complaining’.

In addition, given the discretionary mode of labour management, frequent indebtedness to superiors, and other existing top-down patronage relations, it is always important to maintain some level of compliance to safeguard one’s ‘future’. It may also not necessarily be about being in the good books of supervisors, but also getting wage income to maintain their households. Below, is the story of Adwoa which illustrates the context of acquiescence on the plantation.

Adwoa is a 51-year-old woman who has worked for nine years on the plantation. She is migrant, landless and has been divorced for seven years. She and her former husband had a lot of farm land in their hometown. They even had eight acres of oil palm and she intercropped vegetables. In the early 2000s when they heard of the PSI, they moved to a village in the Eastern Region to work at the nurseries. In the meantime, they left their crops in the hands of family members and that did not work out well. At the same time, her husband had refused to cater for their five daughters under the perception that girls will not bring any wealth to him in future, but rather to their husbands: a reason for their divorce. She has been working all these years to take care of the children’s education. Although she has been a permanent worker upon recruitment, she complains ‘the work is tedious, but if you are not educated do not have any other tradeable skill, what do you do? ‘Now I can see that I’m tired and very weakened’ but what can I do’? She does not envision working until pension, but her goal is to clear the educational costs, and then move to capital city to stay with her children, and perhaps start a trade. Now, she comports herself to safeguard her employment and permanent contract status.

3.3.3. Absenteeism: Production and Action

Everyday resistance also resides in the multitude of alterations or actively constructed responses that are continued and/or created anew in order to confront the modes of ordering that currently dominate our societies [51]. One of the key findings in relation to how the workers respond to casualization and low income is their consciousness about the need to continue with their own farming regardless of the time competition and trade-offs associated with it. Historically, these settler communities emerged out of a ‘dodi’ system, literally meaning ‘cultivate to eat’, whereby natives gave out portions of land freely to settlers to cater for their food needs. Following the fast spread of commodification of the rural, and with cocoa becoming a major cash crop in these areas, the gifting of agricultural lands has become rare, and the system replaced with tenancy agreements. However, farming for subsistence remains an important feature of the people’s social reproduction. As it was evident in the survey conducted, almost everyone cultivated some corn or cassava, and even cash crop sharecroppers are often allowed by their landlords to intercrop some foods for their own subsistence. In addition, in times when they are laid off, some casual workers search for short-term farm labour opportunities such as rice harvesting where the remuneration is paid in bags of rice rather than cash.

Although occasional or seasonal purchases of food items are normal, there is a societal expectation of being able to produce one’s own staple foods or at least to get food crops from one’s land through tenants. In a conversation with a young operator who is also a migrant, he said,

‘I have just acquired a piece of land from my landlord (residential) to plant corn and cassava. My friends have been teasing me and I also realised that I can’t be buying food all the time. They have agreed to support me with their labour to start the farm this year so that I don’t waste my money on food′.

Given this background, the farmworkers’ cash needs are not directly targeted at food even though many depend on the income from the plantation to support their own farms. Apparently, many of the workers use their wages for household needs like educational costs and shelter. Indeed, in 2017, the farm management heeded to the request of the farm residents, many of whom are less landed migrants and allowed them to farm portions of the land that were not maintained—of course, this was also a management strategy to control weed and fire in the unmaintained portions. Nonetheless, the scheme had its shortfalls regarding labour competition and conflicts of interests whereby supervisors were also implicated, thus leading to its annulment after a year. The workers have also been permitted to collect foodstuff13 from the farm, although they are sometimes restricted when it competes with their transport space. In addition, for many casual workers, they could not risk being laid off and being food insufficient at the same time. This consciousness is a major driver for the continuance of their small-scale farming alongside the plantation work. The competition that exists between the planation work and own farming is real, but most of them will not compromise on their own farms to the extent of being short of staple foods. In general, their physical presence on their own farms is reduced and often replaced with hired labour and chemical inputs, but in the faming seasons i.e., during planting and harvesting, they spend ample time on their own farms as compared to the plantation work. Occasionally, some casual farmworkers whose farms are adjacent the plantation, exploit the transport service to work on their farms, without reporting to work. The average number of working days for most of the workers ranges between 18 and 20 days out of the expected even 26/27 days or even lower during the farming seasons. Workers have been seeking for the elimination of Saturday work, but since that has not been granted, more than half of them do not turn up on Saturdays. Interestingly, they do not face sanctions either—a situation which management has come to terms with, given the societal context of their operation. A worker explained:

‘Getting people to work on the farm is difficult. They have to search for a new person, train him or her and hope that he or she stays on. What I can do in 30 min on this farm. A new entrant might use over 2 hours and this will affect the company’.

Indeed, although the company lays of workers seasonally, and also, it is unable to recruit workers to maintain the entire plantation, the narrative above is a true reflection of the daily labour supply challenges. In the classic literature on capitalist development in the countryside as well as the contemporary debates on land grabs [16,31], a major concern has been the issue of surplus population whose labour is not needed on the farm. In this case, although labour appears to be abundant, they is not readily available because of the unfavourable working conditions, the need to subsist, and, of course, their relative access to (tenant) lands to do their own faming, and, in some cases, access to other livelihoods’ opportunities. During my visit in the off-peak season, I had several encounters with laid-off workers in multiple activities. Whereas some, particularly the women, were anxiously waiting to be called back to work; there were also several instances of workers who had been asked to return to work but were not ready. Some were engaged in farming, others were labouring on small scale farms, others had taken up construction contracts, others prioritized their health conditions after previous accidents, while a few young men were considering migrating to cocoa producing regions down south to work as tenant labour14.

4. Discussion

4.1. Contextualising the Farmworkers’ Politics

Several factors account for the emergence of everyday politics as the main form of contention by workers in this case —as we see in their’ demands for minor reforms in the organization and conditions of labour. Of course, the findings re-affirm Scott’s argument that so far as the subsistence ethic of the peasantry is not threatened, revolts are unlikely [42]. In some ways, the maintenance of the moral economy persists as evident in the nature of tenancy agreements that exists between foreigners/settlers and natives. However, when one pulls away from the confines of singular teleological assumptions, then we find several other practical reasons that affect their politics—why everyday actions appear to be the most viable means to expressing their agency and what inhibits their incipient efforts to undertake collective action.

Indeed, everyone on the plantation is there for regular access to cash income, but it is in the unpacking of the purpose of this cash income that we can understand their politics. For instance, a parent’s cash needs her for children’s education normally depends on ages and stages of their dependents, and even the financial demands from the type of educational institutions. The farmworkers who are currently enrolled in secondary or tertiary education or savings towards higher education do not have the incentives to engage in any overt/ organized resistance because they will not stay for long. Similarly, the cash needs for investments in one’s own farm is also a function of the available land size, the form of ownership, access to family labour, the maturity of the farm, types of crops grown, etc. In such instances, their political reactions occur at the conjuncture of self-interest [36] and other structural conditions.

Again, the ways in which labour is structured in a plantation allows permanent workers more organisational opportunities than casual workers. Some permanent workers sometimes schedule their annual leave during their faming season to allow them time on their own farm—of course, worker–supervisor relations play a major role in such decisions. Security workers, who are all permanent staff, have informally re-organized their formal working hours from 12 hours a day to a continuous 48 hours so that they can have two full days every week in order to have ample time for their farm activities and other businesses like motorbike transport services. The situation is however different for casual workers who find it difficult to unite on common issues. In addition, there are always tensions that emerge in their incipient attempts to mobilize. Lower level overseers and headmen are often left in a competing dilemma of whose interest to represent—workers or management? Most of the headmen have been core labourers before, or usually shift between labouring and overseeing, thus many can identify with the challenges faced by workers, yet there is a constant sensitization from management on the need to protect, and explain the company′s position to the workers, so as to prevent any outburst of violence. In the words of one long serving worker,

‘We have attempted a strike before. It landed the headmen in trouble because some workers informed management that the leaders spearheaded it. They [the headmen] were rebuked for that’.

There are several instances of workers doubling as unpaid or paid labourers of their supervisors or other high-ranking authorities in return for favours, small loans, income or gifts, etc., which brings in emotions, fear, and subtle control in their political reactions. ‘Fatherly’ relations between those in authority and workers, is not only typical of many rural settings where paternalistic and patronage relations dominate, but also it is embedded in the existing societal contexts, which is akin to the kind of intergenerational, and top–down relations between the elderly and the young, fathers and sons, chiefs and subjects, teachers and students, etc., characterized by the societal expectation of high regard to authority which often expresses openly or/and subtilty as subordination and control [52].

Transcending the local begs the question, what is the role of the state? Mainstream optimism in large-scale agricultural investments have always been linked to labour opportunities for host communities [29]. However, the growing power and reach of global capital have exceeded the ability of nations and labour movements to regulate them. The existing regulatory institutions for agricultural labour management in Ghana are both inadequate and repressive. First, investors are not bound by any hard laws when it comes to job creation. As they wish, they follow voluntary guidelines or do so as corporate social responsibilities. Second, the existing labour laws in Ghana have been primarily designed for industry and factory workers, not agricultural workers [53]. Third, even when these laws are applicable to farmworkers, they do not address the issues of inequality. The 2003 Labour Act (Act 651) does not apply to piece rate and casual workers, and there are no provisions for dealing with delays in payment of wages. It is therefore not surprising that some workers consider delays as normal, or even better than their previous workplaces. Again, how does one confront a company about low wages when they adhere to labour laws of the country and pay almost 50 percent higher than minimum wage?

The workers’ eagerness to mobilise is constrained on three fronts: not knowing what their rights are, and how to pursue them, thus the fear of possible violation of state laws; their remoteness (location-wise) from the south15 which makes it difficult for alliance building with labour unions; and third, and very importantly, lack of full support from management in their incipient attempts to collectivise – specifically, to join the Ghana Agricultural Workers Union (GAWU). Despite the constitutional safeguarding of workers’ rights to unionization, as at the time of my visit, management had not given approval for security, and casual workers to join the union on the grounds of the company’s internal security and the fluidity of casual workers. While the leaders continue to fight this decision, it is being met with a covert process of false conscientisation about unions being violent. It appears the aim is to inhibit voluntary participation in the union even if management is later compelled to comply with the law. This is often interpreted by the workers as ‘if unions are violent, then it is all about protests and strikes, then there is a likelihood of police arrest’. As such, workers who need to keep their jobs would rather stay away and/or resort to the everyday individualized actions of non-compliance, absenteeism and production.

4.2. Everyday Politics as Weapons of the Weak?

Indeed, the kind of everyday politics that the workers engage in as described above, appears to be the most viable means to expressing their agency in the struggles for better terms of incorporation. However, a question that cannot be escaped is: to what effect are these everyday reactions? Do we risk romanticizing their individualised politics or it could indeed have substantial benefits for peasant farmworkers? Some have argued that casualization in commercial agriculture enables farmworkers to engage in other livelihood occupations [54]. While this remains a fact, for the workers studied, most of them preferred having permanent contracts and with increased incomes as compared to being casual workers—the reason being that most of them who are farmers believe they can substitute much of the time needed on their own farm with hired labour and chemicals if they work under permanent contracts and with increased incomes. In addition, for many others, days off work are opportunities to rest from the tedious work and gain new energy upon resuming. This is indeed good for their health and well-being since they are not entitled to official leave. Unfortunately, this practice also means that they might be forever stuck in the very casual system they despise because commitment is a primary pre-condition for progression. In effect, their politics also become a constraint to their upward mobility in the organization of labour. This goes a long way to affect their income, job security and livelihoods. In an interview with a supervisor, he confirmed,

‘People have been working with us for a very long time, but their attitude towards work is bad. At the time that we need workers for our work, that is when they have left the job to go to their own farms. Sometimes it takes two to three months, especially when it is corn season. Imagine if you engage such a person a permanent worker. Sometimes when you make them permanent, their mentalities change and then you realize that the casual workers even work harder’.

It has been previously illustrated how workers engage in their own production as a major way of expressing their agency to ensure their basic food sovereignty and food security. Nonetheless, the findings demonstrate trade-offs that suggest that all may not be well with their own food production. Access to labour support, farm location and employment contract play key roles in shaping the dynamics of time-labour division between the plantation work and own farming. Many of the workers especially women, indicated that they have had to reduce their farm sizes in order to combine both activities. This means that they usually have just enough for subsistence as compared to the past when they could have surplus harvest. Similarly, some tenants also reported that, as a result of the low yields, their landlords have transferred parts of the tenant lands to more committed farmers. Moreover, in these communities, people often cultivate several crops at different seasons and locations, but what is happening now is that, when it comes food crops, farmworkers now confine themselves to a few staples, mainly corn and cassava. There are other food crops that they could benefit more in terms of food, nutrition and cash, yet it is difficult to combine, as indicated by a harvester,

‘I cultivate yam, groundnuts and cassava and corn. I have always wanted to add ginger but it is time consuming, and the regulations at work place won’t allow me to do so. Corn can never have a better price than ginger’.

While the harvester above seems to be in a better position to cultivate all of those food items, a female proletariat complained bitterly about her inability to cultivate groundnuts as a result of the farm work. At the same time, others also worried about the over reliance on weedicides, paid labour and their inability to maintain their own farms as expected. In fact, some farmers are no longer able to benefit from mutual farm labour support schemes known locally as ‘nnoboa’ because lack of commitment on their part. It however appeared that the youth, as compared to the elderly workers, still found some means to support one another when necessary.

Marxist theorisation on the reproduction of capitalism is often linked to capital’s dependence on non-capitalist societies for land, labour and markets. Reflecting on the extent of semi-proletarianzation and casual work on the plantation, we see that role of labour in the survival of capitalism could even be more complex. The apparent persistence of the peasantry is serving more or less as subsidy to capital accumulation [55]. The peasant farmworkers produce cheap labour, the great majority do not depend on the wages to cover the full cost of their household reproduction especially food, thus they do not revolt—separately and together, a ‘favourable’ condition is created for low cost production on the plantation. As such, although their everyday politics put food on the table, it is more of a reflection of the systemic repression in the agrarian system. Their livelihood strategies and politics all emanate from constrained choices [56], and do not necessarily address the everyday problems faced by peasants—in their case, not getting the full benefits from land and labour.

5. Conclusions

This study set out to examine the dynamics of incorporation into large-scale agricultural land deals, and the political struggles of farm workers against exploitation and for better terms of inclusion. Evidence from the SG Sustainable Oils -Herakles–Volta Red oil palm plantation in Ghana reveals the problématique of unquestioned beliefs in the employment potentials from large-scale agricultural investments. First, the limited employment opportunities, especially for women, and the poor working conditions remind us of how and why capital’s need to maintain its own economic viability/reproduction does not cohere with the presumed social contributions often associated with such investments. Compared to men, women have smaller land sizes, a very small window of employment opportunities and the meagre incomes, and are less likely to rise above their ranks as labourers. The precarious working conditions characterised by casualization, low incomes, indebtedness, and poor occupational health and safety are in themselves a disincentive to labour supply and retention. Conscious of how they have been adversely incorporated into the plantation work, farmworkers strive to gain some benefits through everyday forms of resistance and reactions. Through non-compliance, absenteeism, and production, they carry a strong political message that ‘they are people entitled to be treated with dignity and entitled livelihood’ [57]. They do so to ensure access to food, extra income, rest and well-being. While the general conditions of work are not favourable, the extent of impacts, and their diverse individualised politics are influenced not only by class relations, but also the relations in the organisation of labour which is also embedded in, and reinforced by existing social structures of inequality. Thus, unlike common notions of everyday politics as being highly empowering, their everyday actions are themselves situated within very narrow options and therefore they cannot be romanticised as entirely liberating. Organised collective action is still very necessary for negotiating better terms of incorporation. The findings from this single case cannot be used to draw generalised conclusions about land grabs, but certainly, it serves as reference point to caution against oversimplified assumptions on the impacts of large-scale investments in fragile rural communities. In other words, the differentiated dynamics of impacts challenge mainstream ideals of win–win outcomes even when local communities tap into some here-and-then livelihood benefits. Unless rural policies are designed to address structural inequalities and disparities in the relations in production, such investments should not be promoted.

Funding

The International Institute of Social Studies provided financial support to conduct field work for this research.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Jun Borras, Yukari Sekine, and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the BICAS conference in Brasília, 2018 and I thank the participants for helpful comments. I’m also grateful to Kenneth Kankam, Richmond Sem, Hasiya Alhasan, Prince Asare for their support in data processing, and I thank Kwaku Owusu Twum for the study location map.

Conflicts of Interest

“The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Amanor, K.S. Global Resource Grabs, Agribusiness Concentration and the Smallholder: Two West African Case Studies. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, P. The Land Grab and Corporate Food Regime Restructuring. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, M.; McKeon, N.; Borras, S. Land Grabbing and Global Governance: Critical Perspectives. Globalizations 2013, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation? An Introduction to Land Grabbing and Political Reactions ‘from Below.’ . J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 467–488. [Google Scholar]

- Mamonova, N. Resistance or Adaptation? Ukrainian Peasants’ Responses to Large-Scale Land Acquisitions. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 607–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larder, N. Space for Pluralism? Examining the Malibya Land Grab. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniello, G. Social Struggles in Uganda’s Acholiland: Understanding Responses and Resistance to Amuru Sugar Works. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulle, E. Social Differentiation and the Politics of Land: Sugar Cane Outgrowing in Kilombero, Tanzania. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2016, 43, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte, M.J. La Vía Campesina, Brazilian Peasants, and the Agribusiness Model of Agriculture: Towards an Alternative Model of Agrarian Democratic Governance. Stud. Polit. Econ. 2010, 85, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.A.; Sauer, S. Rural Unions and the Struggle for Land in Brazil. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 1109–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K. Global Restructuring and Land Rights in Ghana: Forest Food Chains, Timber, and Rural Livelihoods; Afrikainstitutet, Nordiska: Uppsala, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yaro, J.A.J.; Teye, J.K.J.; Torvikey, G.D. Agricultural Commercialisation Models, Agrarian Dynamics and Local Development in Ghana. J. Peasan. Stud. 2017, 44, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, F. How and Why Chiefs Formalise Land Use in Recent Times: The Politics of Land Dispossession through Biofuels Investments in Ghana. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2014, 41, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulmin, C.; Gueye, B. Transformation in West African Agricultures and the Role of Family Farms. Sahel West Africa Club (SWAC/OECD) SAH/D 2003, 241, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Lenin, V.I. The Development of Capitalism in Russia; Progress Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1964; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. Capital: Volume One. Karl Marx Sel. Writ. 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The New Imperialism; Oxford: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kautsky, K. The Agrarian Question; Swan: London, UK, 1899; Volumes I-II. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, H. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change; Fernwood Pub.: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lerche, J. From Rural Labour to Classes of Labour. In The Comparative Political Economy of Development; Harris-White, B., Heyer, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- White, B. Problems in the Empirical Analysis of Agrarian Differentiation. Agrarian Transformations: Local Processes and the State in Southeast Asia. G. Hart, A. Turton and B. White. Berkeley; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Oya, C. The Empirical Investigation of Rural Class Formation: Methodological Issues in a Study of Large- and Mid-Scale Farmers in Senegal. Hist. Mater. 2004, 12, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreda, T. Large-Scale Land Acquisitions, State Authority and Indigenous Local Communities: Insights from Ethiopia. Third World Q. 2016, 6597, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S. Shifting Burdens: Gender and Agrarian Change under Neoliberalism; Kumarian Press: Sterling, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman, J.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Quisumbing, A. The Gender Implications of Large-Scale Land Deals. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss-White, B. Inequality at Work in the Informal Economy: Key Issues and Illustrations. Int. Labour Rev. 2003, 142, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Corta, L.; Venkateshwarlu, D. Unfree Relations and the Feminisation of Agricultural Labour in Andhra Pradesh, 1970–95. J. Peasant Stud. 1999, 26, 71–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavoni, C.M. The Contested Terrain of Food Sovereignty Construction: Toward a Historical, Relational and Interactive Approach. J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 44, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD; FAO; IFAD; World Bank Group. Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment That Respects Rights, Livelihoods and Resources; A Discussion Note; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2008; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. Centering Labor in the Land Grab Debate. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, A.; Hickey, S. Adverse Incorporation, Social Exclusion, and Chronic Poverty. In Chronic Poverty; Rethinking International Development Series; Shepherd, A., Brunt, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, A. Adverse Incorporation and Agrarian Policy in South Africa. Or, How Not to Connect the Rural Poor to Growth; University of Western Cape: Cape Town, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K. Making Negotiated Land Reform Work: Initial Experience from Colombia, Brazil, and South Africa. World Dev. 1999, 27, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M. Can Small Farmers Survive, Prosper, or Be the Key Channel to Cut Mass Poverty? Electron. J. Agric. Dev. Econ. 2006, 3, 58–85. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, S. The Rational Peasant: The Political Economy of Rural Society in Vietnam; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Duggett, M. Marx on Peasants. J. Peasant Stud. 1975, 2, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenin, V.I. The Differentiation of the Peasantry. In Rural Development: Theories of Peasant Economy and Agrarian Change; John, H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1982; pp. 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Paige, J. A Theory of Rural Class Conflict. In Agrarian Revolution; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Thorner, D. Chayanov’s Concept of Peasant Economy. In The Theory of Peasant Economy; The American Economic Association: Homewood, IL, USA, 1966; pp. xi–xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Shanin, T. The Nature and Logic of the Peasant Economy—II: Diversity and Change: III. Policy and Intervention. J. Peasant Stud. 1974, 1, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Weapons of the Weak. In Every Day Forms of Peasant Resistance; Yale University Press: New Haven, CO, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D. Everyday Resistance or Routine Repression? Exaggeration as a Stratagem in Agrarian Conflict. J. Peasant Stud. 2001, 29, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, D. Oil Palm Industry Growth in Africa: A Value Chain and Smallholders’ Study for Ghana. In Rebuilding West Africa’s Food Potential; FAO/IFAD: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, G.B.; Rallis, S.F. Learning in the Field: An Introduction to Qualitative Research; SAGE: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A.; Tsikata, D. Policy Discourses on Women’s Land Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Implications of the Re-Turn to the Customary. J. Agrar. Chang. 2003, 3, 67–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S. Engendering the Political Economy of Agrarian Change. J. Peasant Stud. 2009, 36, 197–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Laughlin, B. Consuming Bodies: Health and Work in the Cane Fields in Xinavane, Mozambique. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2017, 43, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.; Peluso, N. A Theory of Access. Rural Sociol. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, K. Land and Labour: The Micro Politics of Land Grabbing in Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. The Peasantries of the Twenty-First Century: The Commoditisation Debate Revisited. J. Peasant Stud. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K. Family Values, Land Sales And Agricultural Commodification In South-Eastern Ghana. Afr. J. Int. Afr. Inst. 2010, 80, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ghana. The Labour Act; GoG Official Gazette: Accra, Ghana, 10th October 2003.

- Cramer, C.; Oya, C.; Sender, J. Lifting the Blinkers: A New View of Power, Diversity and Poverty in Mozambican Rural Labour Markets. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2008, 46, 361–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxemburg, R. The Accumulation of Capital.; Monthly; Monthly Review Press LCCN: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Gyapong, A.Y. Family Farms, Land Grabs and Agrarian Transformations: Some Silences in West African Food Sovereignty Discourses. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of the BRICS Initiative for Critical Agrarian Studies [New Extractivism, Peasantries and Social Dynamics: Critical Perspectives and Debates] Conference, Moscow, Russia, 13–16 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkvliet, B.J.T. Everyday Resistance to Injustice in a Philippine Village. J. Peasant Stud. 1986, 13, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | This number fluctuates due to the large number of casual workers. |

| 3 | Total valid respondents. |

| 4 | Referring to land purchased, not necessarily inherited or accessed through family. |

| 5 | A popular term used by the farmworkers especially women to describe the physical health as a result of intensity of labour. |

| 6 | The official numbers could be lower than the actual numbers because some have worked without contracts, such as the use of students in the past, occasional task sharing by family members, the carriers who work unofficially with harvesters, and others who are temporally hired when there is urgent need for workers- e.g., fire control. |

| 7 | Approx. 2.9 USD as of September 2018. |