One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Midcentury Southwest: A Showcase for Urban Renewal

3.1.1. Rationale for Renewal

3.1.2. Characteristics of the Renewal Zone

3.1.3. Short-Term Impacts of the Urban Renewal Project

3.2. Then to Now—Changing Paradigm for Urban Planning

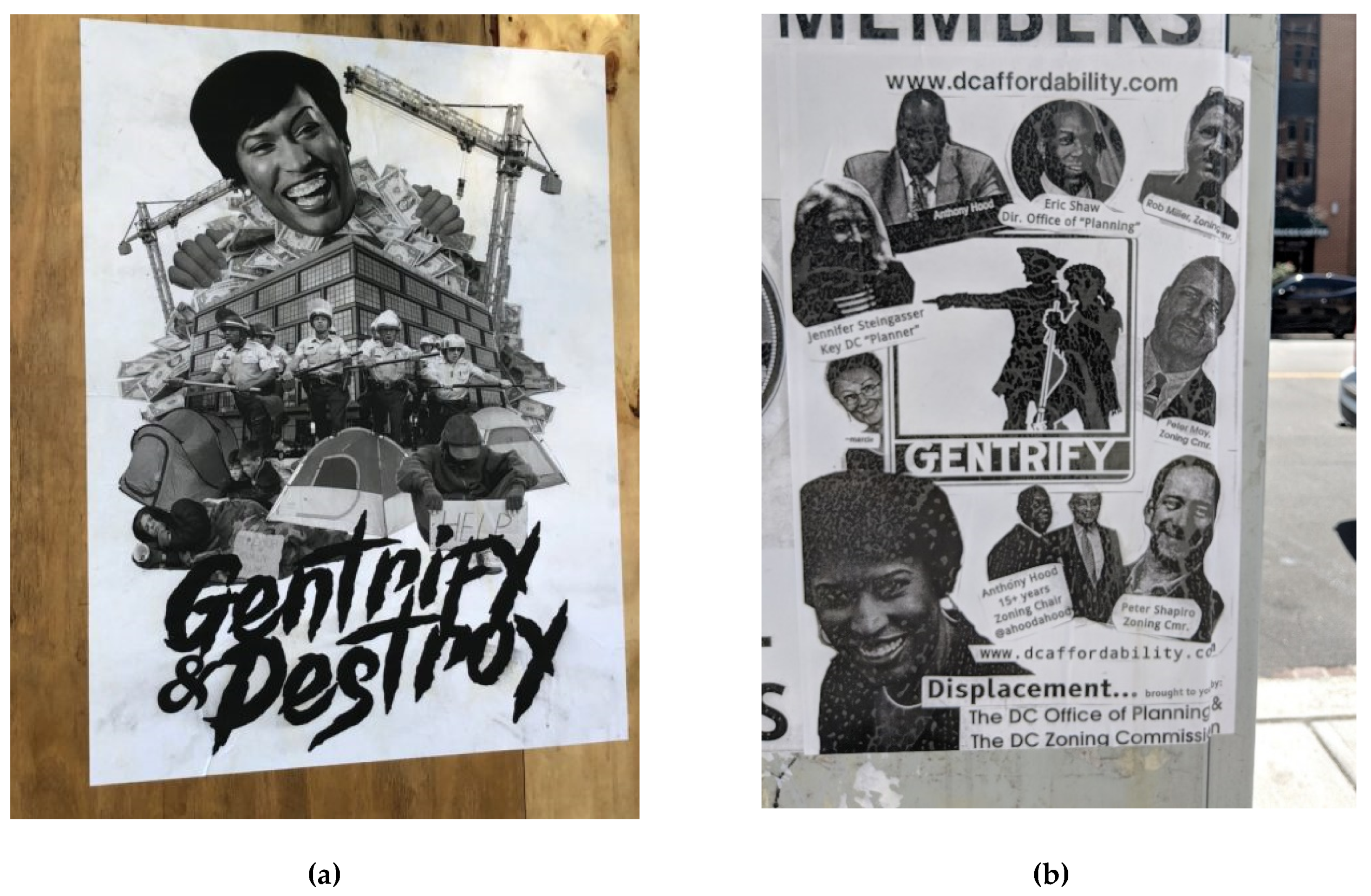

3.3. Forces of Displacement in Present-Day DC

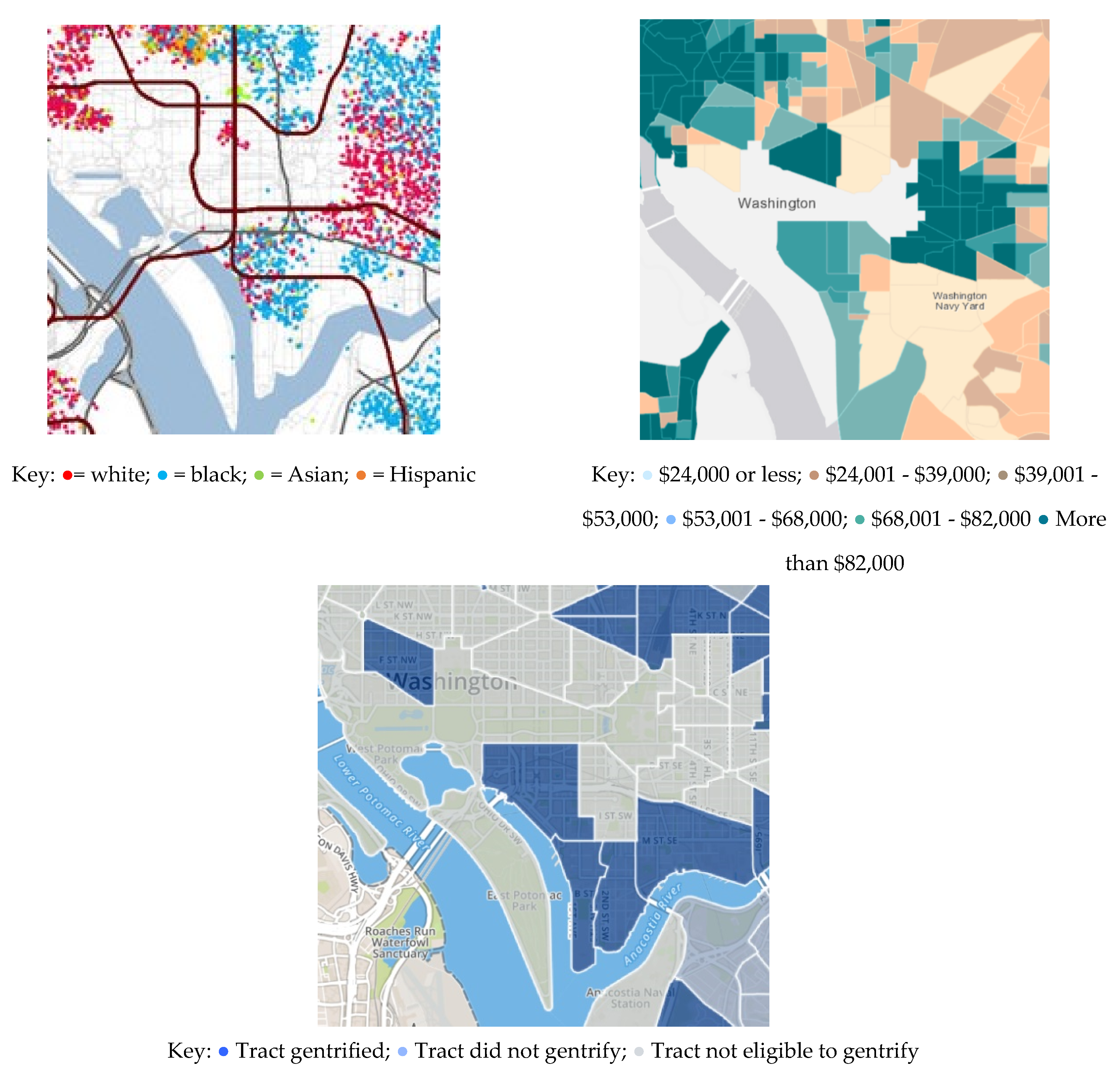

3.3.1. Systemic Inequalities Reflected in Settlement Patterns

3.3.2. Potential Drivers of Forced Displacement in Washington, DC

- Rapid population growth. The city’s population growth of 13.2% from 2010 to 2016 has outpaced a 5% increase in housing stock [31].

- Housing size preferences. Preference by smaller households to occupy larger units (both rent and purchase) resulting in increased competition for family-sized units [31].

- Limited physical space. High land costs and limited physical space in DC have resulted in an emphasis on infill development or rehabilitation [32].

- Mismatch between housing stock and incomes. From 2005 to 2012, the availability of luxury rental units increased and availability of affordable rental units decreased. Meanwhile, housing costs increased faster than incomes in the DC region [33] (Figure 4). DC’s Gini coefficient as of 2016 was higher than that of all 50 states [34].

3.3.3. Potential Drivers of Responsive Displacement

3.4. Assessing Mobilities in DC through the Lens of the Southwest Quadrant

3.4.1. Southwest: What Does Renewal of Urban Renewal Mean for Residents?

3.4.2. Case Studies in SW

Wharf Development

Greenleaf Gardens

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Park Service. Southwest Washington, Urban Renewal Area. HABS DC-866. Historic American Buildings Survey. Available online: https://www.swdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/HABS-Southwest-Washington-Urban-Renewal-Area.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2018).

- Shin, A. Brave Old World. Washington City Paper. 2 May 2003. Available online: https://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/arts/article/13026580/brave-old-world (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Meyer, E.L. Contrite over Failed Urban Renewal, Washington D.C. Refreshes a Waterfront. The New York Times. 18 November 2014. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/19/realestate/commercial/washington-dc-refreshes-a-waterfront.html (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Government of the District of Columbia. Southwest Neighborhood Plan. 2016. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/doc/271584684/Council-Approved-Southwest-Neighborhood-Plan (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Green, R.D.; Mulusa, J.K.; Byers, A.A.; Parmer, C. The Indirect Displacement Hypothesis: A Case Study in Washington, D.C. Rev. Black Political Econ. 2017, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, K. Preservation from the bottom-up: Affordable housing, redevelopment and negotiation in Washington, DC. Hous. Stud. 2016, 31, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyra, D. The back-to-the-city movement: Neighbourhood redevelopment and processes of political and cultural displacement. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1753–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. Displacement or Succession? Residential Mobility in Gentrifying Neighborhoods. Urban Aff. Rev. 2005, 40, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuk, M.; Bierbaum, A.H.; Chapple, K.; Gorska, K.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Gentrification, Displacement, and the Role of Public Investment. J. Plan. Lit. 2018, 33, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, K. Income Inequality and Urban Displacement: The New Gentrification. New Labor Forum 2017, 26, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. Commentary 21st Century Gentrification. Cityscape 2016, 18, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, L. The New District of Columbia: What Population Growth and Demographic Change Mean for the City. J. Urban Aff. 2014, 36, 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnish, T.; Walsh, R.; White, T.K. Who gentrifies low-income neighborhoods? J. Urban Econ. 2010, 67, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrar, M. Building the Body Politic: Power and Urban Space in Washington, D.C.; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, A. Who Says ‘No One’s From D.C.? Not Black Washingtonians. WAMU. 19 October 2017. Available online: https://wamu.org/story/17/10/19/says-no-ones-d-c-not-black-washingtonians/ (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- United States National Capital Planning Commission; Gutheim, F.; Lee, A. Planning the City of Tomorrow, 1952–1960. In Worthy of the Nation: Washington, DC, from L’Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission, 2nd ed.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2006; pp. 256–285. [Google Scholar]

- Longstreth, R. Brave New World: Southwest Washington and the Promise of Urban Renewal. In Housing Washington: Two Centuries of Residential Development and Planning in the National Capital Area; Longstreth, R., Ed.; Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; pp. 255–280. [Google Scholar]

- Esri [2018]. World Imagery. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=10df2279f9684e4a9f6a7f08febac2a9 (accessed on 26 June 2018).

- Liston, D. Summary of Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26. OLR Research Report; 1954. Available online: https://www.cga.ct.gov/2013/rpt/2013-R-0211.htm (accessed on 26 December 2018).

- Pritchett, W.E. The “Public Menace” of Blight: Urban Renewal and the Private Uses of Eminent Domain. Faculty Scholarship Paper 1199. 2003. Available online: http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1199 (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Russello Ammon, F. Commemoration Amid Criticism: The Mixed Legacy of Urban Renewal in Southwest Washington, D.C. J. Plan. Hist. 2009, 8, 175–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.; Jung, K. Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States. U.S. Census Bureau Working Paper No. 76; 2005. Available online: https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Thursz, D. Where Are They Now? A Study of the Impact of Relocation on Former Residents of Southwest Washington, Who Were Served in an HWC Demonstration Project; Health and Welfare Council of the National Capital Area: Washington, DC, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- DC Housing Authority (2018). Public Housing Areas. Available online: https://maps2.dcgis.dc.gov/dcgis/rest/services/DCGIS_DATA/Public_Service_WebMercator/MapServer/15 (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- Gale, D.E. Washington, D.C.: Inner City Revitalization and Minority Suburbanization; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Darden, E.M. Neighborhood Renewal: Reinvestment and Displacement in D.C.; A Report/Prepared by the District of Columbia Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights; The Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, A. A New Show about Neighborhoods Facing Gentrification Offers a Cautionary Tale. 9 May 2018. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/new-show-about-neighborhoods-facing-gentrification-offers-cautionary-tale-180969032/ (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Johnson, M. Maps show racial divides in Greater Washington. Adapted from Eric Fischer. 2010. Available online: https://ggwash.org/view/6497/maps-show-racial-divides-in-greater-washington. (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- ESRI. Wealth Divides: An Interactive Income Inequality Map. 2015. Available online: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/these-maps-help-explain-numerous-complicated-factors-behind-income-inequality-180955941/ (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- Governing Magazine Governing. Washington, DC, Gentrification Map: 2000 Census – Present. In Washington, DC, Gentrification Maps and Data. Available online: http://www.governing.com/gov-data/washington-dc-gentrification-maps-demographic-data.html (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- Taylor, Y.S. Taking Stock of the District’s Housing Stock: The Full Report. D.C. Policy Center. Available online: https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/taking-stock-full-report/ (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Hickey, R.; Sturtevant, L. Public Land & Affordable Housing in the Washington, D.C. Region: Best Practices and Recommendations. Urban Land Institute, 2015. Available online: http://washington.uli.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/56/2015/02/ULI_PublicLandReport_Final020215.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Blumenthal, P.; McGinty, J.R.; Pendall, R. Strategies for Increasing Housing Supply in High-Cost Cities: DC Case Study. Urban Institute, 2016. Available online: https://nvaha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2000907-Strategies-for-Increasing-Housing-Supply-in-High-Cost-Cities-DC-Case-Study.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Naveed, M. Income Inequality in DC Highest in the Country [Blog Post]. D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute, 2017. Available online: https://www.dcfpi.org/all/income-inequality-dc-highest-country/ (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Zippel, C. DC Can’t Afford to Lose the Low-Cost Housing It Has Left. Capital Community News. Available online: http://www.capitalcommunitynews.com/content/dc-can%E2%80%99t-afford-lose-low-cost-housing-it-has-left-0 (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Office of the District of Columbia Auditor. Stronger Management of the Housing Production Trust Fund Could Build More Affordable Housing. 20 March 2018. Available online: http://www.dcauditor.org/sites/default/files/HPTF.Database.Report.3.20.18.FINAL_.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- DC Fiscal Policy Institute. The Local Rent Supplement Program. Available online: https://www.dcfpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/16-04-LRSP-Brief.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Kohanzadah, H. Taxes in the District: The Evolution of DC Tax Rates since the Early 2000s. DC Fiscal Policy Institute, 2 May 2018. Available online: https://www.dcfpi.org/all/taxes-in-the-district-the-evolution-of-dc-tax-rates-since-the-early-2000s/ (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Zippel, C. Building the Foundation: A Blueprint for Creating Affordable Housing for DC’s Lowest-Income Residents. DC Fiscal Policy Institute, 2018. Available online: https://www.dcfpi.org/all/building-the-foundation-a-blueprint-for-creating-affordable-housing-for-dcs-lowest-income-residents/ (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- O’Toole, A.; Jones, B. Tenant Purchase Laws as a Tool for Affordable Housing Preservation: The D.C. Experience. J. Afford. Hous. Community Dev. Law 2009, 18, 367–388. [Google Scholar]

- Popville. But are they for or against Initiative 77? [blogpost]. 15 June 2018. Available online: https://www.popville.com/2018/06/but-are-they-for-or-against-initiative-77/ (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Schweitzer, A. D.C.’s Plan for Future Growth Fails Low-Income Residents, Activists Say. WAMU. 21 March 2018. Available online: https://wamu.org/story/18/03/21/d-c-s-plan-future-growth-fails-low-income-residents-activists-say/ (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Poll: White Residents in D.C. Think Redevelopment Helps Them. Black Residents Don’t. Washington Post. 20 November 2015. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/poll-white-and-wealthy-residents-in-dc-think-redevelopment-helps-them-black-and-poor-residents-dont/2015/11/19/bb7acbca-8ed6-11e5-ae1f-af46b7df8483_story.html?utm_term=.6b5e0a3a85cb (accessed on 25 June 2018).

- Southwest Business Improvement District. SWBid: By the Numbers. 2017. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59160436ff7c50511f6f72cc/t/5a0c52428165f525baf4adc4/1510756934876/By+the+Numbers+2017.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- United States Census Bureau. Census Tracts in 2010. Available online: http://opendata.dc.gov/datasets/6969dd63c5cb4d6aa32f15effb8311f3_8 (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Boivie, I. Lessons from the Waterfront: Economic Development Projects Must Do More to Lesson DC’s Worsening Income Inequality. DC Fiscal Policy Institute, 2017. Available online: https://www.dcfpi.org/all/lessons-waterfront-economic-development-projects-must-lessen-dcs-worsening-income-inequality/ (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Gilgore, S. The Wharf’s Phase II is Up Next, and With It Comes Opposition. Washington Business Journal. 2 November 2017. Available online: https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2017/11/02/the-wharf-s-phase-ii-is-up-next-and-with-it-comes.html (accessed on 7 January 2019).

- District of Columbia Housing Authority. Request for Qualifications Solicitation No. 0006-2018. Greenleaf Housing Community Co-Developer, 2018. Available online: http://www.dchousing.org/docs/2017121810073284810.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Kramer, F. Greenleaf Redevelopment Raises Major Concerns. HillRag. 19 June 2018. Available online: http://hillrag.com/2018/06/19/greenleaf-redevelopment-raises-major-concerns/ (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum. A Right to the City. Available online: http://anacostia.si.edu/Exhibitions/Details/A-Right-to-the-City-6222 (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- De Paula, N. The “Right to the City” and the New Urban Agenda. IISD. 12 July 2016. Available online: http://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/policy-briefs/the-right-to-the-city-and-the-new-urban-agenda/ (accessed on 13 January 2019).

| 1950 | 1970 | 2000 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 21,050 | 9,427 | 8,802 |

| Black | 69% | 32% | 57% |

| White | 31% | 67% | 33% |

| Median household income (in 1999 dollars) | $14,000 | $53,000 | $43,000 |

| Owner-occupied housing units | 15% | 22% | 35% |

| Renter-occupied housing units | 81% | 76% | 59% |

| Mean gross rent (in 1999 dollars, monthly) | $239 | $938 | $721 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lindsay-Herrera, F. One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC. Land 2019, 8, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8020034

Lindsay-Herrera F. One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC. Land. 2019; 8(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleLindsay-Herrera, Flora. 2019. "One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC" Land 8, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8020034

APA StyleLindsay-Herrera, F. (2019). One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC. Land, 8(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8020034