Development of Urban Digital Twins Using GIS and Game Engine Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

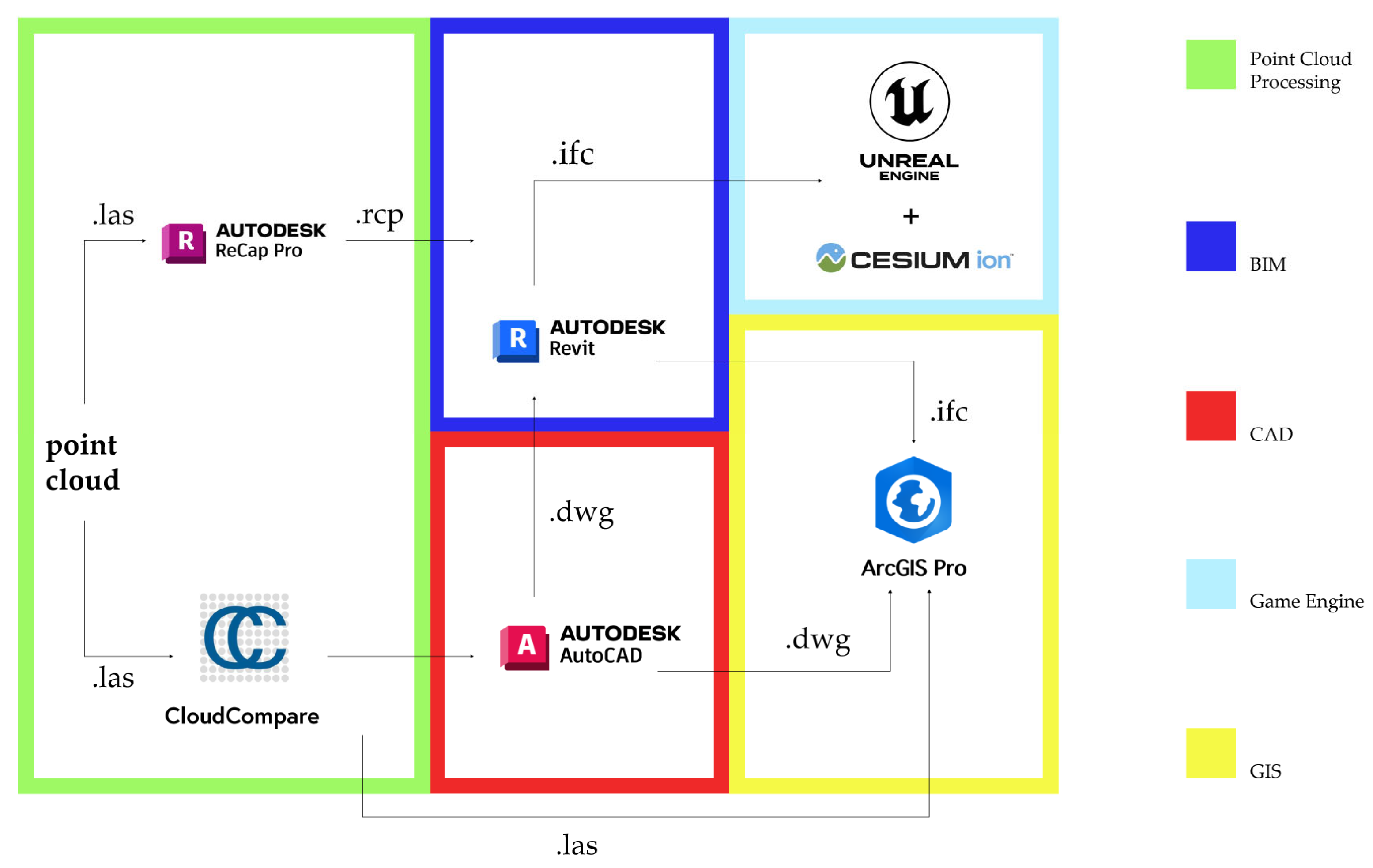

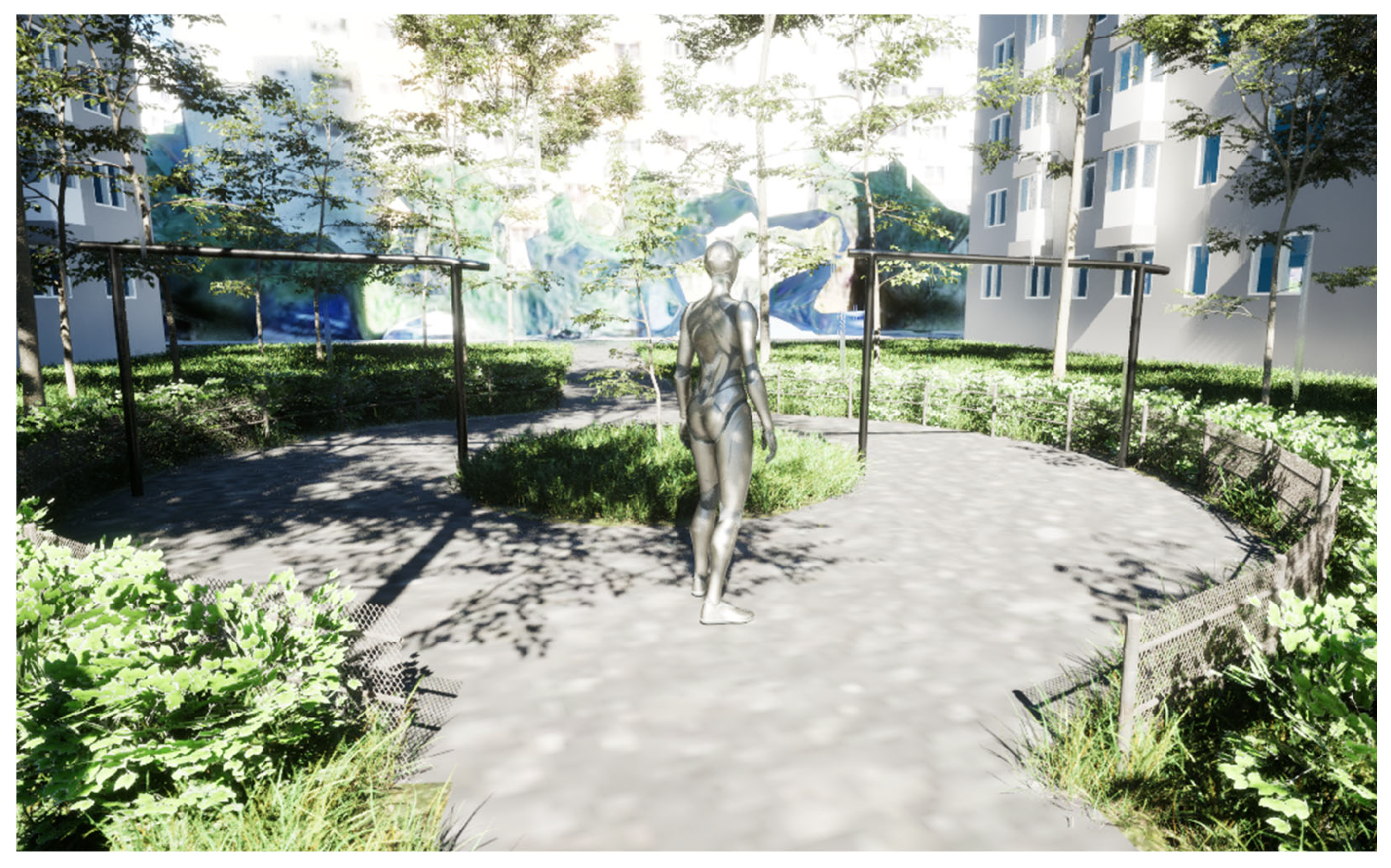

2. Materials and Methods

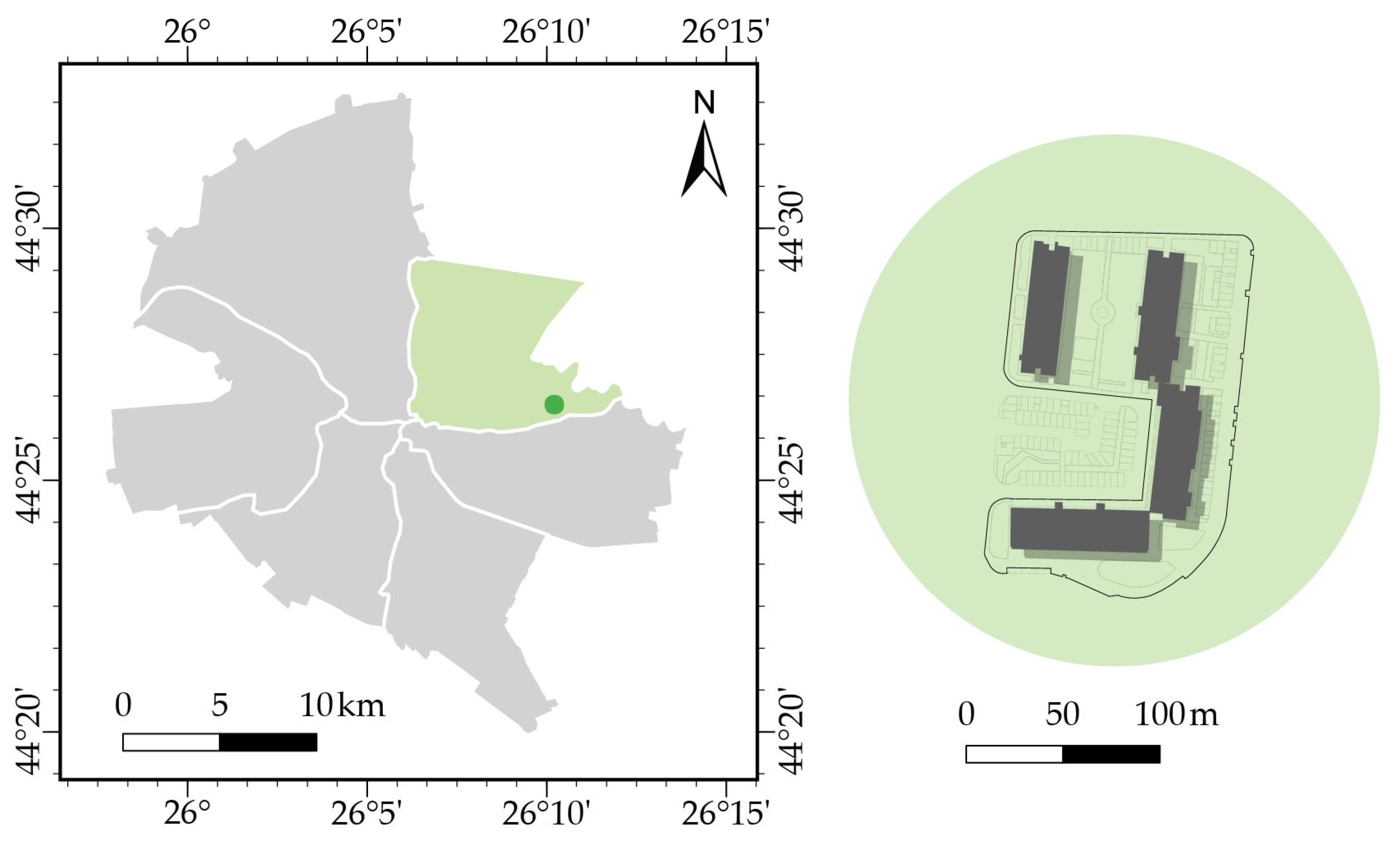

2.1. Study Area

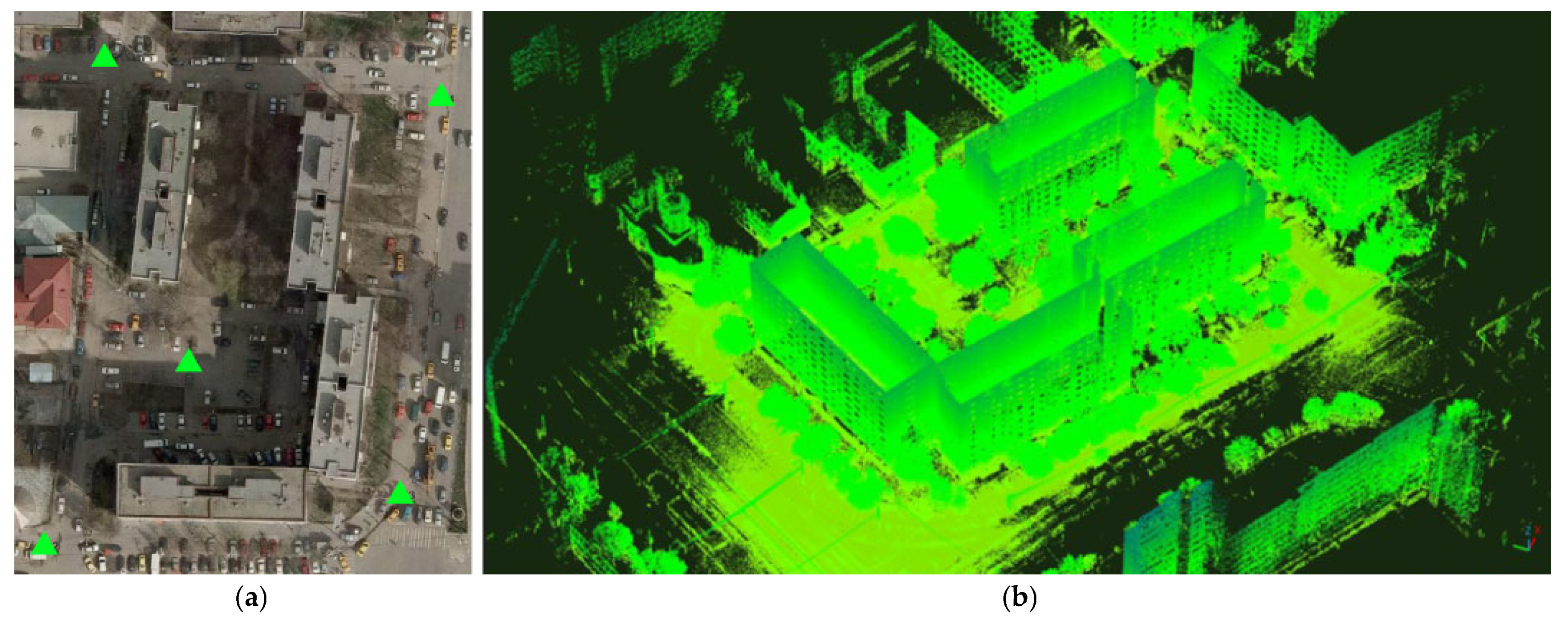

2.2. Geospatial Data Acquisition

2.3. Overall Workflow Designs

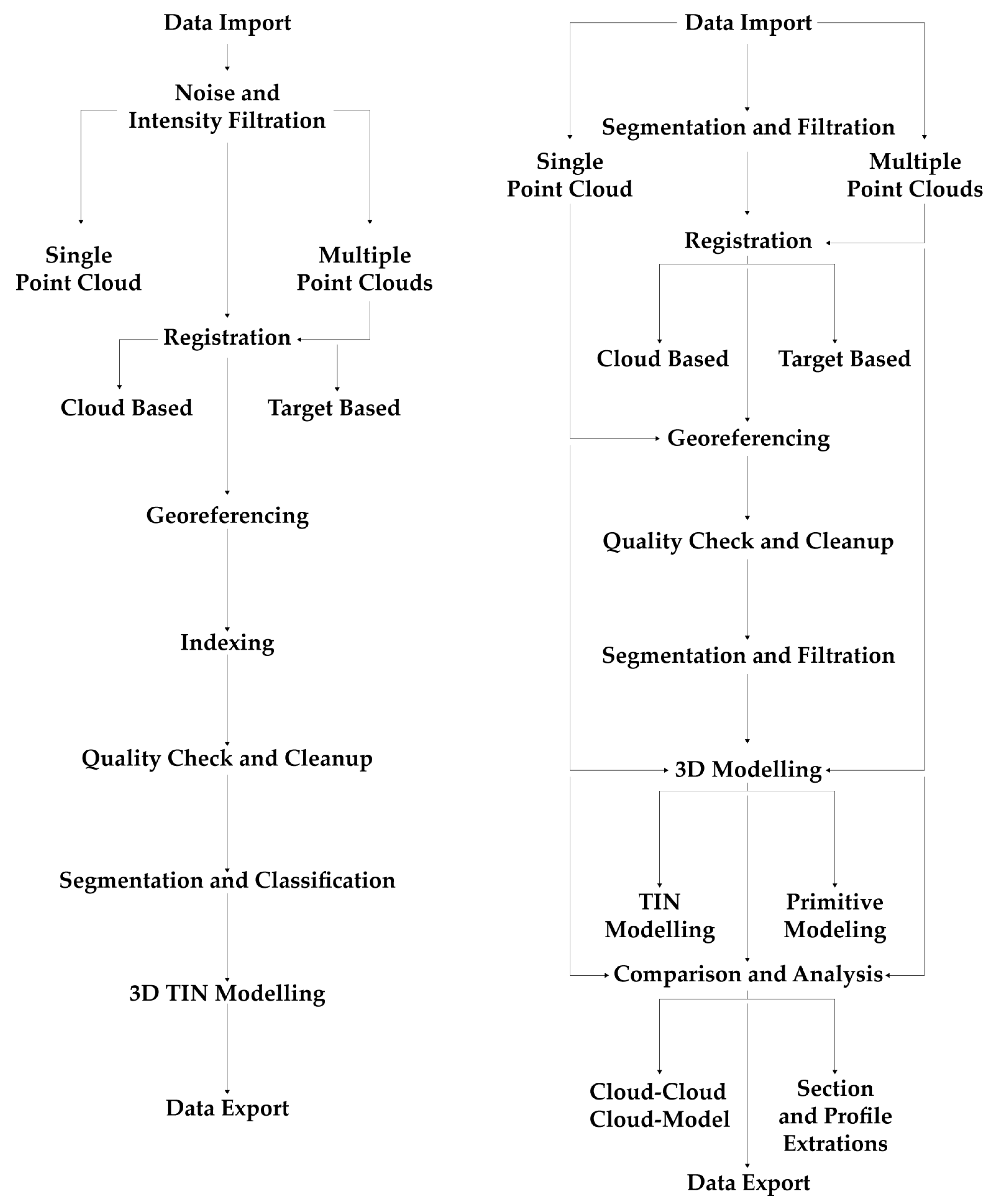

2.3.1. Point Cloud Processing

2.3.2. Three-Dimensional Modeling

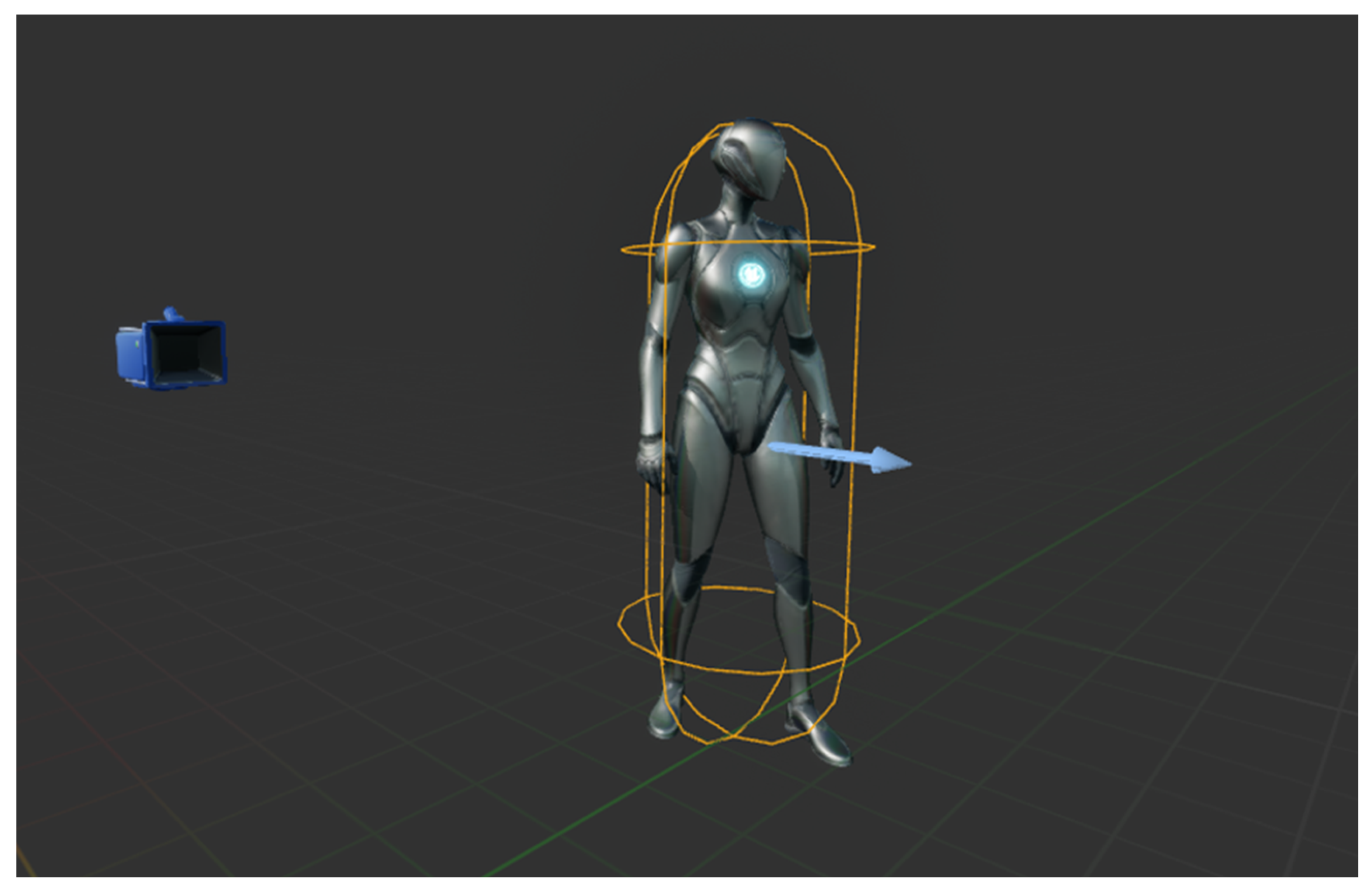

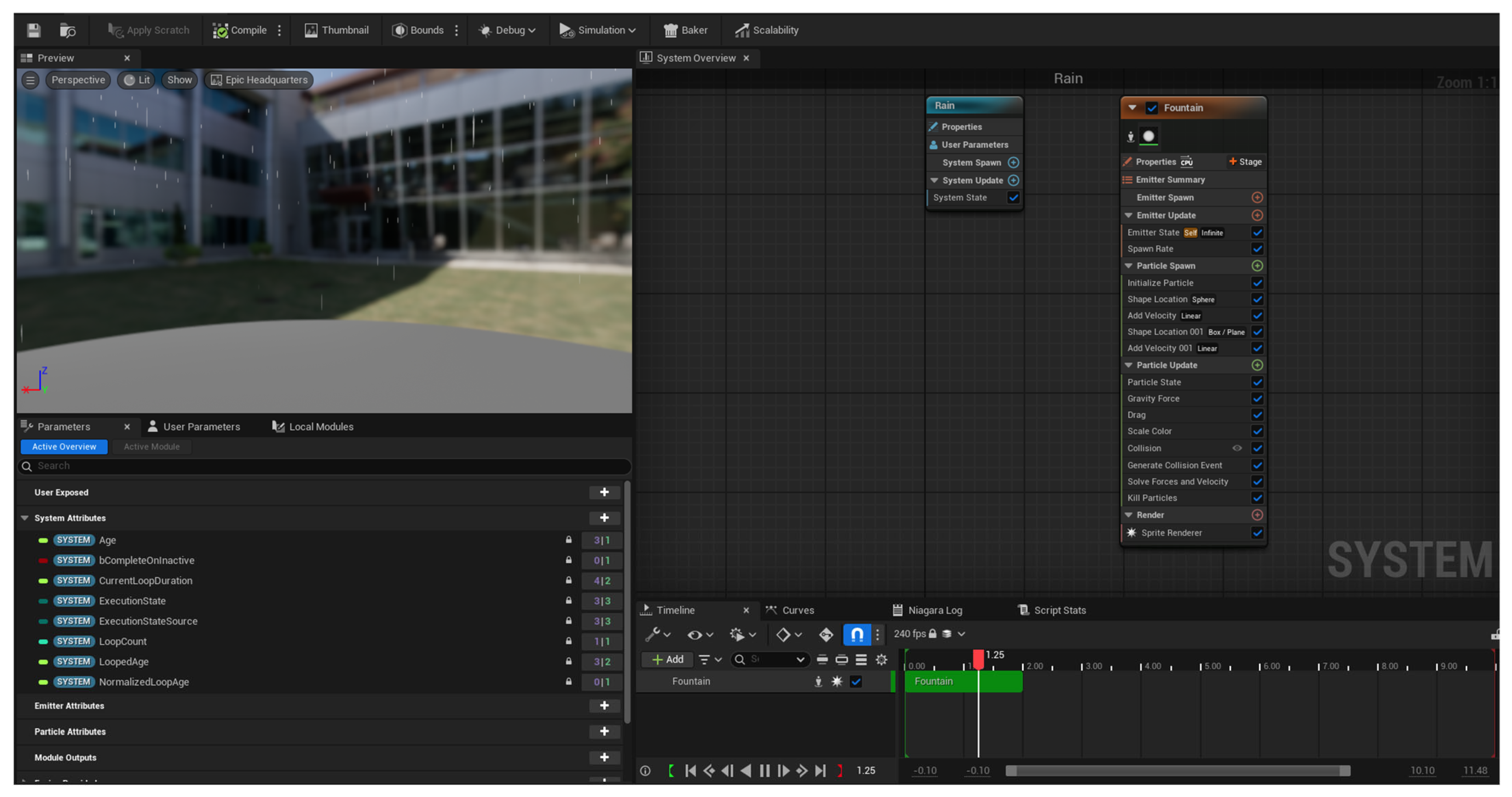

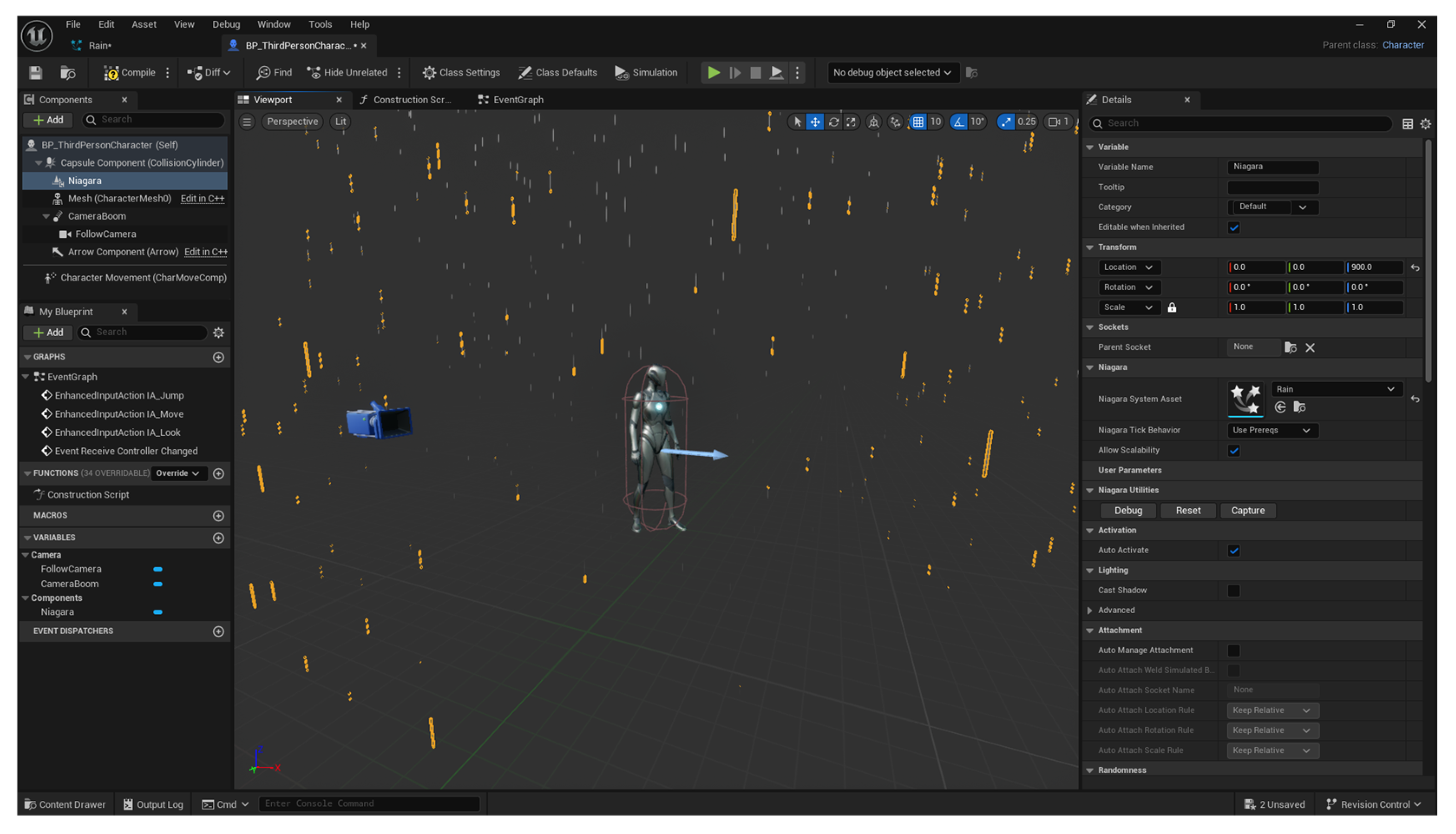

2.3.3. Data Integration and Processes in Unreal Engine

2.4. Hardware and Software Requirements

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DT | Digital Twin |

| UDT | Urban Digital Twin |

| CAD | Computer Aided Design |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| XR | Extended Reality |

| IFC | Industry Foundation Classes |

| OGC | Open Geospatial Consortium |

| CityGML | City Geography Markup Language |

| LoD | Level of Detail |

| UE5 | Unreal Engine 5 |

| LAS | LASer—file containing LiDAR point cloud data |

| RCP | Revit Point Cloud |

References

- Ritchie, H.; Samborska, V.; Roser, M. Urbanization. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Luan, W.; Li, X. Rapid urbanization and its driving mechanism in the Pan-Third Pole region. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Beltran-Velamazan, C.; Monzón-Chavarrías, M.; López-Mesa, B. A Method for the Automated Construction of 3D Models of Cities and Neighborhoods from Official Cadaster Data for Solar Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Minner, J. UAVs and 3D City Modeling to Aid Urban Planning and Historic Preservation: A Systematic Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C.A.; Lombillo, I.; Sánchez-Espeso, J.M.; Balbás, F.J. A New Approach to 3D Facilities Management in Buildings Using GIS and BIM Integration: A Case Study Application. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguslawski, P.; Zlatanova, S.; Gotlib, D.; Wyszomirski, M.; Gnat, M.; Grzempowski, P. 3D building interior modelling for navigation in emergency response applications. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 114, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ke, F.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H. Multi-Scale Analysis of Land Use Transition and Its Impact on Ecological Environment Quality: A Case Study of Zhejiang, China. Land 2025, 14, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, C.; Kolbe, T.H. Applications for Semantic 3D Streetspace Models and Their Requirements—A Review and Look at the Road Ahead. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljecki, F.; Stoter, J.; LeDoux, H.; Zlatanova, S.; Çöltekin, A. Applications of 3D City Models: State of the Art Review. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2015, 4, 2842–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Suman, R. Digital Twin applications toward Industry 4.0: A Review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, G.; Bourgeois, I.; Rodrigues, H. A holistic methodology for the assessment of Heritage Digital Twin applied to Portuguese case studies. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2025, 36, e00390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, A.A.H.; Supangkat, S.H.; Lubis, F.F.; Nugraha, I.G.B.B.; Kinanda, R.; Rizkia, I. Development of a Smart City Platform Based on Digital Twin Technology for Monitoring and Supporting Decision-Making. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.W. Digital Twins: Past, Present, and Future. In The Digital Twin; Crespi, N., Drobot, A.T., Minerva, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, M.; Wang, H. Digital twin applications in aviation industry: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 5677–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, H.; Chang, Q.; Mao, Q. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twins Technology in Agriculture. Agriculture 2025, 15, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, M.; Pacchiano, F.; Ferraciolli, S.F.; Criscuolo, S.; Gagliardo, C.; Jaber, K.; Angelicchio, M.; Briganti, F.; Caranci, F.; Tortora, F.; et al. Medical Digital Twin: A Review on Technical Principles and Clinical Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Sharma, A.; Tran, B.; Alahakoon, D. A systematic review of digital twins for electric vehicles. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 11, 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, F.; Brumana, R.; Salvalai, G.; Previtali, M. Digital Twin and Cloud BIM-XR Platform Development: From Scan-to-BIM-to-DT Process to a 4D Multi-User Live App to Improve Building Comfort, Efficiency and Costs. Energies 2022, 15, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, M.; Celik, B.G. Digital Twin: Benefits, use cases, challenges, and opportunities. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 6, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, A.; Hasan, A.; Osen, O.; Mikalsen, E.T. Predictive digital twin for offshore wind farms. Energy Inf. 2023, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J. Digital Twin Technology in the Gas Industry: A Comparative Simulation Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. A Review of Urban Digital Twins Integration, Challenges, and Future Directions in Smart City Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, S.; Kasraian, D.; Nourian, P.; van Wesemael, P. What Have Urban Digital Twins Contributed to Urban Planning and Decision Making? From a Systematic Literature Review Toward a Socio-Technical Research and Development Agenda. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, C.; Bibri, S.E.; Longchamp, R.; Golay, F.; Alahi, A. Urban Digital Twin Challenges: A Systematic Review and Perspectives for Sustainable Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswick, B.; Pankratz, Z.; Glowacki, M.; Lu, Y. Re-(De)fined Level of Detail for Urban Elements: Integrating Geometric and Attribute Data. Architecture 2024, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrotter, G.; Hürzeler, C. The Digital Twin of the City of Zurich for Urban Planning. PFG 2020, 88, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, A.; Lavoratti, G. Documenting Urban Morphology: From 2D Representations to Metaverse. Land 2024, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, A.C.; Badea, G. Geospatial Development Using GIS Smart Planning. BulletinUASVM Hortic. 2019, 76, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adade, D.; De Vries, W.T. A systematic review of digital twins’ potential for citizen participation and influence in land use agenda-setting. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, F.N.; Shirowzhan, S.; Sepasgozar, S.M.E. Citizen-centric digital twin development with machine learning and interfaces for maintaining urban infrastructure. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 84, 102032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, A.; Badea, A.C.; Badea, G.; Grădinaru, A.P. Urban Data Integrated Management and Scenario Development in the Context of Achieving SDG Indicators. RevCAD 2024, 36, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen, T.; Julin, A.; Virtanen, J.-P.; Hyyppä, H.; Vaaja, M.T. Open Geospatial Data Integration in Game Engine for Urban Digital Twin Applications. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, L.M.B.; Mesquita, S.P.B.S.; Treccani, D.; Adami, A. Comparative Assessment of Point Cloud Annotation Workflows for Applications in Architectural and Spatial Studies. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 48, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antova, G.; Peev, I. Comparison on Commercial and Free Software for Point Cloud Processing. Inżynieria Miner. 2024, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Hopkinson, C. 3D Graph-Based Individual-Tree Isolation (Treeiso) from Terrestrial Laser Scanning Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OGC City Geography Markup Language (CityGML) 3.0 Conceptual Model Users Guide. Available online: https://www.opengis.net/doc/UG/CityGML-user-guide/3.0 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Kyaw, K.S.S.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Bohne, R.A. Influences of BIM-LOD and Geographic-Scale Environmental Impact Factors on embodied emissions: The Norwegian context. Build. Environ. 2025, 269, 112345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unreal® Engine End User License Agreement. Available online: https://www.unrealengine.com/en-US/eula/unreal (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Unreal Engine. Available online: https://www.unrealengine.com/en-US/datasmith (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Barrile, V.; La Foresta, F.; Calcagno, S.; Genovese, E. Innovative System for BIM/GIS Integration in the Context of Urban Sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CESIUM Ion. Available online: https://cesium.com/platform/cesium-ion/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Uttley, J.; Canwell, R.; Smith, J.; Falconer, S.; Mao, Y.; Fotios, S.A. Does darkness increase the risk of certain types of crime? A registered report protocol. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0291971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakonjac, I.; Zorić, A.; Rakonjac, I.; Milošević, J.; Marić, J.; Furundžić, D. Increasing the Livability of Open Public Spaces during Nighttime: The Importance of Lighting in Waterfront Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Air Quality Monitoring Network Map. Available online: https://regreeneration.claritech.ro/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Ehab, A.; Aladawi, A.; Burnett, G. Exploring AI-Integrated VR Systems: A Methodological Approach to Inclusive Digital Urban Design. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PPeldon, D.; Banihashemi, S.; LeNguyen, K.; Derrible, S. Navigating urban complexity: The transformative role of digital twins in smart city development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 111, 105583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Zhang, K.; Shen, Z.-J. A systematic review of a digital twin city: A new pattern of urban governance toward smart cities. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2021, 6, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, W.; Cornelissen, H.; Borst, J.; Klerkx, R.; Araghi, Y.; Walraven, E. Building digital twins of cities using the Inter Model Broker framework. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 148, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovský, M. Pre-Dam Vltava River Valley—A Case Study of 3D Visualization of Large-Scale GIS Datasets in Unreal Engine. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Peng, C.; Yoshinaga, T.; Han, G.; Guleng, S.; Wu, C. Digital Twin-Enabled Internet of Vehicles Applications. Electronics 2024, 13, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somanath, S.; Naserentin, V.; Eleftheriou, O.; Sjölie, D.; Wästberg, B.S.; Logg, A. Towards Urban Digital Twins: A Workflow for Procedural Visualization Using Geospatial Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-haghi, M.S.; Anitescu, C.; Rabczuk, T. Methods for enabling real-time analysis in digital twins: A literature review. Comput. Struct. 2024, 297, 107342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yessef, M.; Hakam, Y.; Tabaa, M.; Alammar, M.M.; Elbarbary, Z.M.S. Digital twin technology in smart cities: A step toward intelligent urban management. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Hietala, H.; Xu, Y.; Liyanage, R. Stakeholders collaborations, challenges and emerging concepts in digital twin ecosystems. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2024, 169, 107424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.; Hussain, M.I. A light-weight dynamic ontology for Internet of Things using machine learning technique. ICT Express 2021, 7, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Jia, F.; Cheng, X. Digital twin-supported smart city: Status, challenges and future research directions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 217, 119531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grădinaru, A.P.; Badea, A.C.; Ene, A.; Badea, G. The integration of geospatial analyses based on AI in GIS in the context of the “15-minute city” concept. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 608, 05008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, H.A.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Sohail, A.; Ahmed, R.; Butt, M.H.; Ullah, H. Geographic Information System and Machine Learning Approach for Solar Photovoltaic Site Selection: A Case Study in Pakistan. Processes 2025, 13, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhitaryan, K.; Sanamyan, A.; Mnatsakanyan, M.; Kirakosyan, E.; Ratner, S. Integrating AI and Geospatial Technologies for Sustainable Smart City Development: A Case Study of Yerevan. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochmair, H.; Juhász, L.; Li, H. Advancing AI-Driven Geospatial Analysis and Data Generation: Methods, Applications and Future Directions. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Hu, Q.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; He, P.; Zhu, D.; Kornejady, A. Harnessing Game Engines and Digital Twins: Advancing Flood Education, Data Visualization, and Interactive Monitoring for Enhanced Hydrological Understanding. Water 2024, 16, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makai, P.K. Video Games as Objects and Vehicles of Nostalgia. Humanities 2018, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, H. Re-Calibrating Steampunk London: Heterotopia and Spatial Imaginaries in Assassins Creed: Syndicate and The Order 1886. Humanities 2021, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Software | CloudCompare | Autodesk ReCap Pro |

|---|---|---|

| License/Cost | Open-source | Commercial |

| Free | Subscription-based | |

| Platform | Windows, macOS, Linux | Windows, Cloud |

| Domain of Use | Architecture, Design, Urban Planning, Engineering, Construction | Architecture, Engineering, Construction |

| Processing Functions and Analysis | Registration, segmentation, filtering, clustering, classification, cloud-to-cloud distance, cloud-to-mesh distance, model-to-model, cross-sections, statistical and geometrical tools | Registration, clean-up, noise reduction, region selection, clipping, measurements tools |

| UI/Accessibility | Standalone Technical, moderate learning curve | Standalone Intuitive, accessible for beginners |

| Import Formats | BIN, LAS, E57, PTS, PTX, RCS, PCD, ASC, TXT, NEU, XYZ, XYB, PLY, OBJ, STL, VTK, FLS, FWS, DXF, FBX, JPEG, SHP, GeoTIFF, CSV | CL3, CLR, E57, FLS, FWS, LSPROJ, LAS, PCG, PRJ, PTG, PTS, PTX, RCS, RDS, TXT, XYB, XYZ, ZFS, ZFPRJ |

| Export Formats | BIN, LAS, E57, PTS, PTX, RCS, PCD, ASC, TXT, NEU, XYZ, XYB, PLY, OBJ, STL, VTK, FLS, FWS, DXF, FBX, JPEG, SHP, GeoTIFF, CSV | E57, PTS, PCG, RCP, RCS |

| Plugin | Role |

|---|---|

| Datasmith (Datasmith C4D Importer, Datasmith CAD Importer, Datasmith Content, Datasmith Importer) (v1.0) | Imports pre-design built assets from 3D modeling software (3ds Max, Revit, SketchUp, Rhino 3D, SolidWorks, CATIA, CAD, and IFC formats [40]) |

| Cesium for Unreal (v2.16.0) | Adds the 3D geospatial context of the real world |

| FAB (v0.0.4) | Provides access to the Epic Games marketplace |

| Quixel Bridge (v2025.0.3) | Gives access to the Megascans library (materials, environments, and MetaHumans) |

| Niagara (v1.0) | Creates weather visual effects |

| Hardware/Sofware | AutoCAD | ArcGISPro | CloudCompare | Autodesk Revit | Unreal Engine | 1st System Specifications | 2nd System Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | 4–8 logical cores/8+ logical cores | 2 cores/6–10+ cores | Quad-core/8+ cores | Modern multi-core CPU/up to 16+ cores for large models | Quad-core/8–32+ cores | AMD Ryzen 7 5800H 3.20 GHz | AMD Ryzen 9 7950X 16-Core Processor (4.50 GHz) |

| RAM | 8 GB/32–64 GB | 8 GB/32–64+ GB | 8–16 GB/32–128 GB | 4–8 GB/16–64+ GB | 16 GB/32–128 GB | 16.0 GB | 32.0 GB |

| GPU | 2 GB/8+ GB VRAM (DX12) | OpenGL support/4+ GB dedicated GPU | OpenGL support/modern GPU | DirectX 11 capable GPU with Shader Model 5/~4 GB VRAM | DirectX 12/RTX-class GPU with 8+ GB VRAM | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 Laptop GPU (6 GB) | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Ti SUPER (32 GB) |

| Storage | HDD or SSD/NVMe SSD | NVMe SSD | NVMe SSD | 30 GB minimum/SSD | SSD/NVMe SSD | 954 GB SSD NVMe | Corsair MP700 PRO NVMe 932 GB |

| Motherboard | Standard motherboard | Standard board with high RAM capacity | Scalable standard platform | Modern standard platform (Windows 10/11 64-bit) | PCIe 4.0/5.0 chipset, high-quality VRM, PSU 750–1200 W | Windows 10—64-bit | Windows 11Pro 64-bit |

| Geospatial Data | Format | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Building footprints, light poles, pathways | .dwg | Topographic plans |

| Parking spaces, sidewalks | shapefiles | Bucharest’s District 2 GIS database |

| Green spaces, trees, tree species | .dwg | Landscape plan |

| Three-dimensional model | IFC | authors |

| Sensor data network | - | https://regreeneration.claritech.ro/ (accessed on 4 December 2025) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ene, A.; Badea, A.C.; Badea, G.; Grădinaru, A.-P. Development of Urban Digital Twins Using GIS and Game Engine Systems. Land 2026, 15, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020254

Ene A, Badea AC, Badea G, Grădinaru A-P. Development of Urban Digital Twins Using GIS and Game Engine Systems. Land. 2026; 15(2):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020254

Chicago/Turabian StyleEne, Anca, Ana Cornelia Badea, Gheorghe Badea, and Anca-Patricia Grădinaru. 2026. "Development of Urban Digital Twins Using GIS and Game Engine Systems" Land 15, no. 2: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020254

APA StyleEne, A., Badea, A. C., Badea, G., & Grădinaru, A.-P. (2026). Development of Urban Digital Twins Using GIS and Game Engine Systems. Land, 15(2), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020254