Global Change: Impacts on Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Systems in Campo de Cartagena (Region of Murcia, Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- ▪

- Precipitation (PPT, mm month−1)

- ▪

- Potential evapotranspiration (PET, mm month−1)

- ▪

- Surface runoff (q, mm month−1)

- ▪

- Maximum and minimum air temperature (TMAX, TMIN, °C)

- ▪

- Standardized Precipitation-Evaporation Index (SPEI)

3. Results

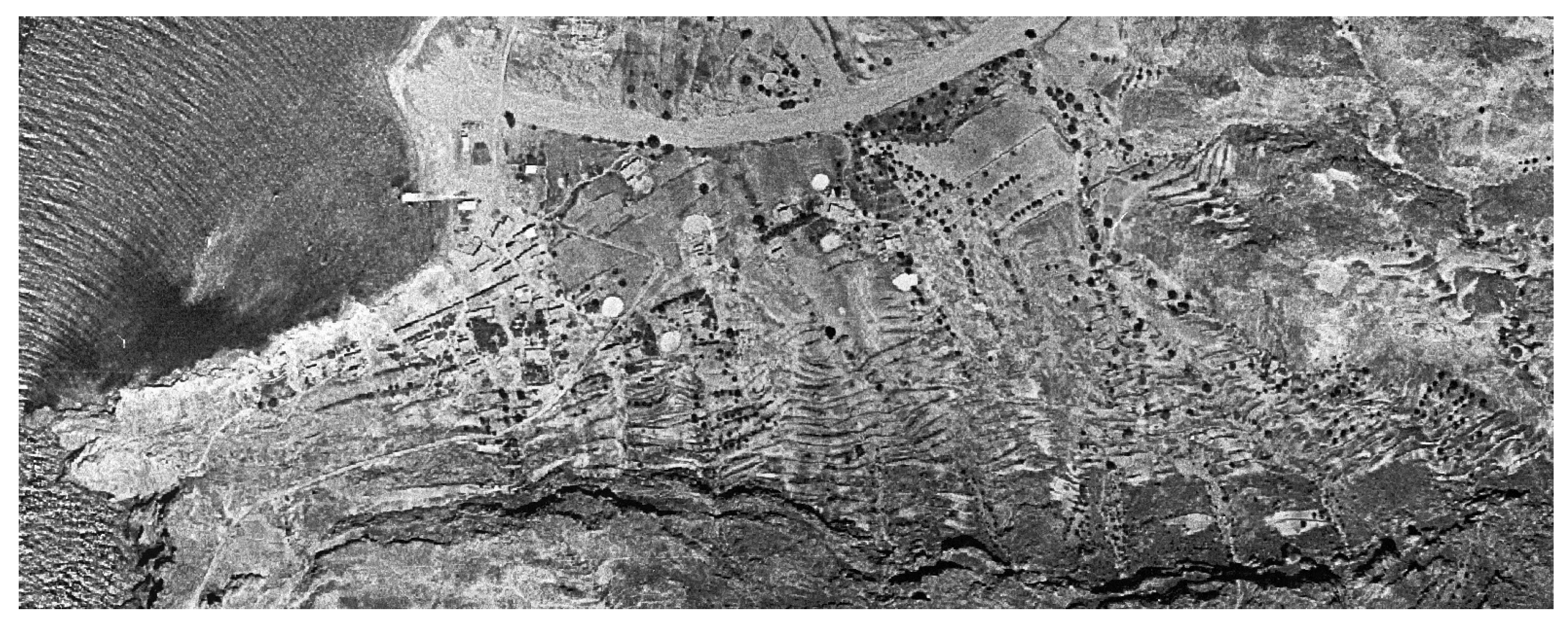

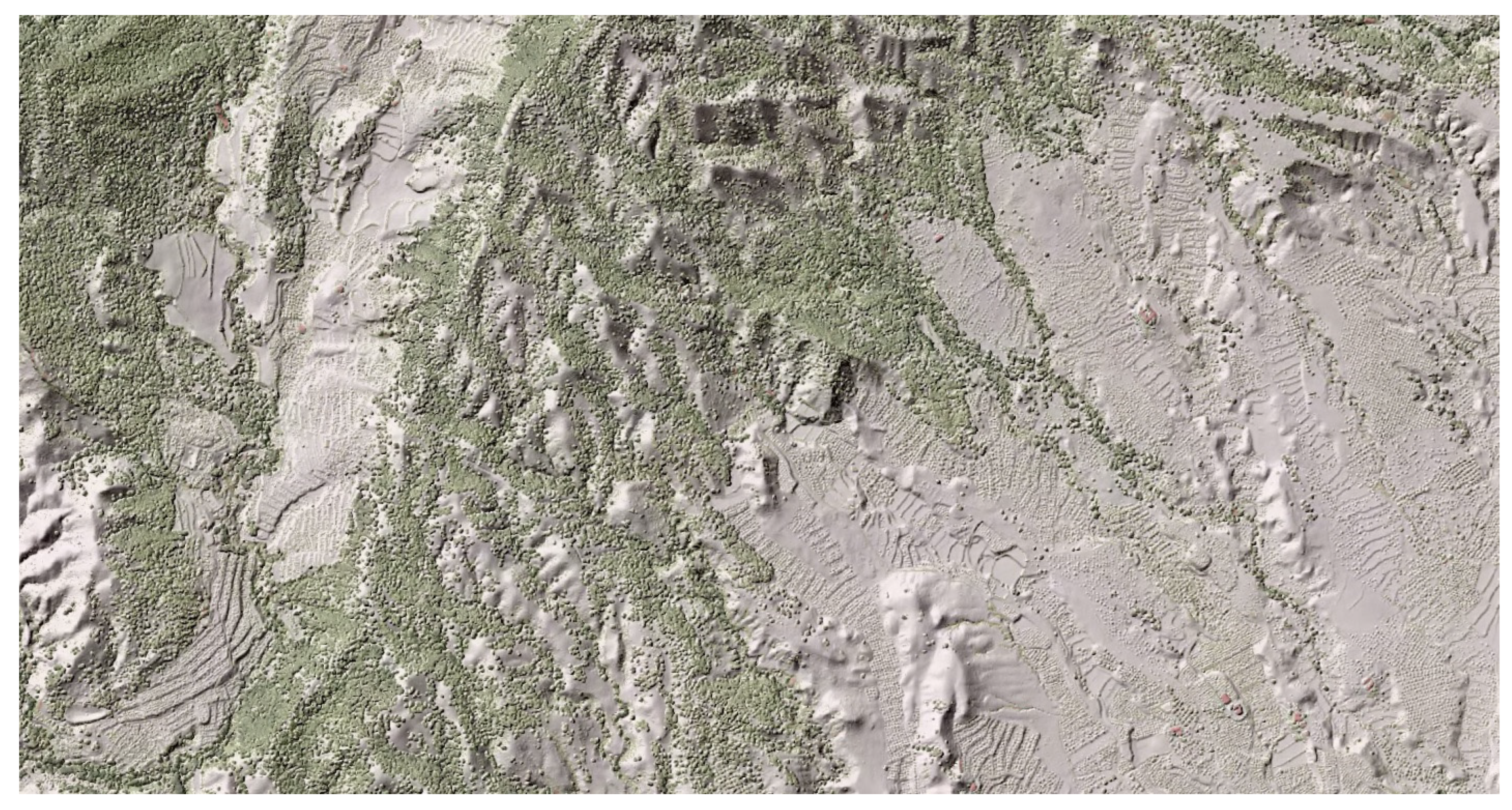

3.1. Geolocation and Spatial Analysis of the Location Records of Traditional Rainwater Harvesting (RWH) Systems in Campo De Cartagena

3.1.1. Cisterns

3.1.2. Derivation Dums and Rainfall Channels

3.1.3. Terracing

3.2. Main Effects of Global Change on Campo De Cartagena

3.2.1. Modification of the Land Uses in Campo De Cartagena

3.2.2. Climate Alteration

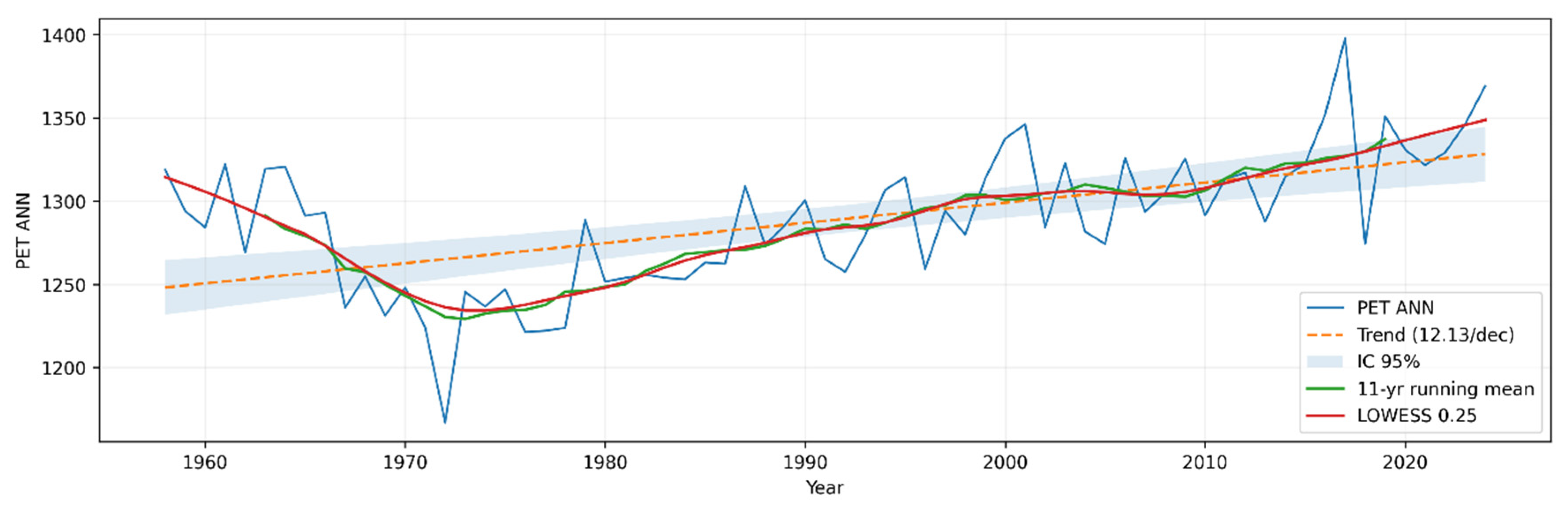

- Potential evapotranspiration (PET)

- Runoff variability and hydrological implications

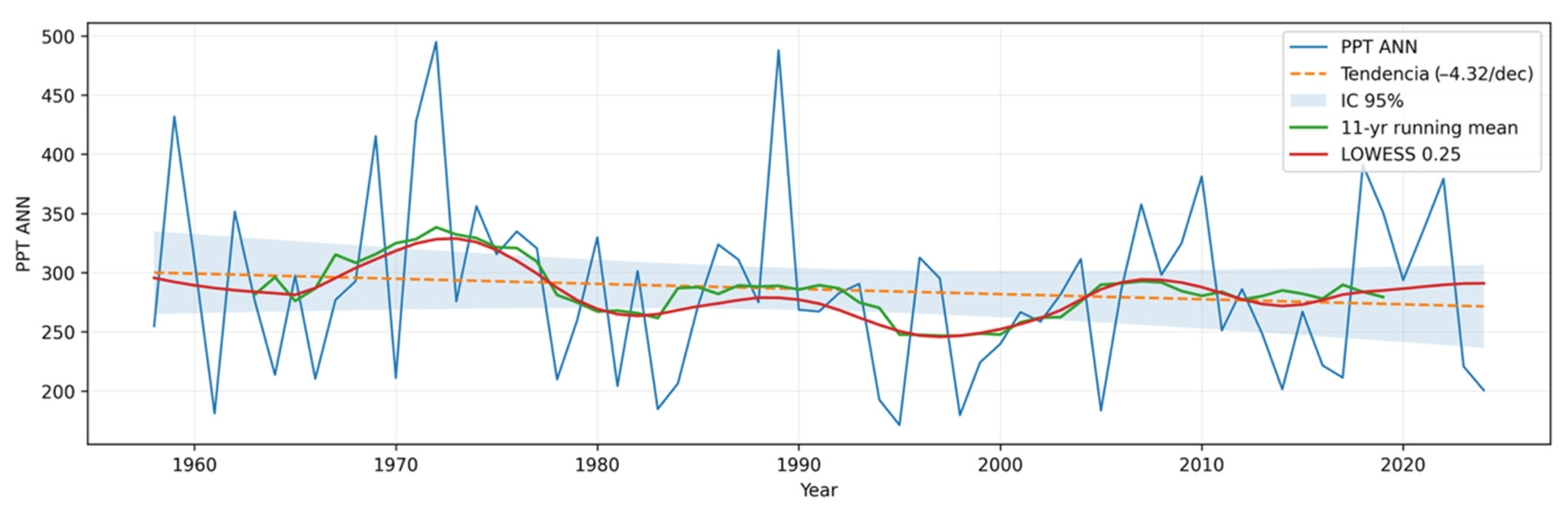

- Precipitation variability and long-term trends

- Trends in Maximum Temperature (TMAX).

- Trends in Minimum Temperature (TMIN).

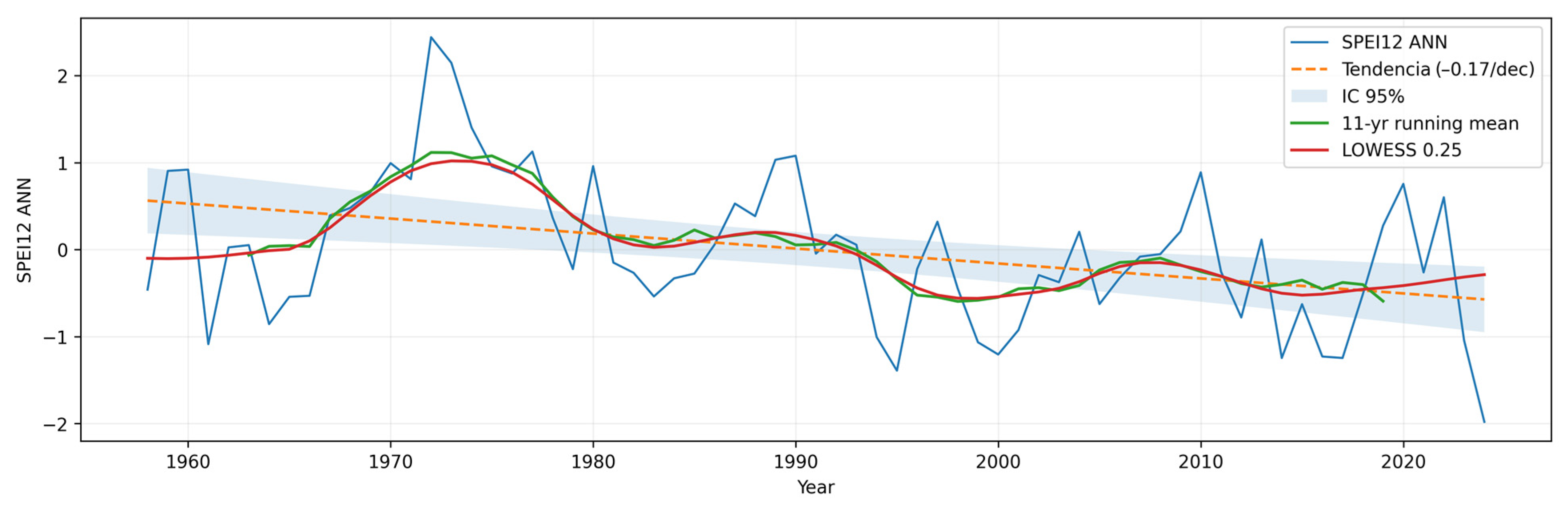

- Long-term meteorological drought conditions (SPEI-12).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Núm. 221. Sábado 13 September 2025. Resolución de 4 de septiembre de 2025. |

| 2 | UNESCO: https://ich.unesco.org/es/ (accesed on 1 December 2025) |

| 3 | A concept that has recently evolved into “Anthropogenic global change” [8]. |

| 4 | Georeferenced cartographic sheets that have been downloaded from the CNIG and subsequently loaded into the GIS, thus renouncing the use of the orthocomposite mosaic available via WMS connection, since this alters part of what is represented in the original documents. |

| 5 | Coordination of Information on the Environment (CORINE). |

| 6 | These are classified into Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3, increasing in detail from the first to the last. |

References

- Conesa García, C. Clima e Hidrología Del Campo de Cartagena; Editum: Murcia, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Amestoy Alonso, J.; Amestoy García, J. Precipitaciones, Aridez, Sequía y Desertificación de la Comarca Del Campo de Cartagena. Lurralde Investig. Y Espac. 2009, 32, 119–154. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Carrasco Pleite, F.; Schwentesius-Rinder-mann, R.; Martínez-Paz, J.M.; Gómez-Cruz, M.Á. Características y comparativa de los productores de alimentos ecológicos en el sureste de Europa: El caso de la Región de Murcia, España. Agrociencia 2009, 43, 649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Castejón Porcel, G.; Espejo Marín, C. Aprovechamiento agrario de la Región de Murcia (España) y el municipio de Fuente Álamo de Murcia: Análisis comparado, 1999-2020. Ería. Rev. Cuatrimest. Geogr. 2024, 44, 103–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, T.; Li, J.; Alverson, K. (Eds.) Global Change and Future Earth: The Geoscience Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sage, D. Global Change: Transformations in Human–Environment Relations; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C.M.; Alonso, S.; Benito, G.; Dachs, J.; Montes, C.; Pardo Buendía, M.; Valladares, F. Cambio Global. Impacto de la Actividad Humana Sobre el Sistema Tierra; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C.M. Global change and the future ocean: A grand challenge for marine sciences. Front. Mar. Sci. 2014, 1, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García González, M.B.; Jordano, P. (Coords.); Global Change Impacts; (CSIC) Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, M.; Martín-Díaz, J.; Lozano, C.B.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Bonsoms, J. (Eds.) Cambio Global: Crisis Ecosocial y Perspectivas Futuras; Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Graveline, N.; Majone, B.; Van Duinen, R.; Ansink, E. Hydro-economic modeling of water scarcity under global change: An application to the Gállego river basin (Spain). Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 14, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallart, F.; Delgado, J.; Beatson, S.J.V.; Posner, H.; Llorens, P.; Marcé, R. Analysing the effect of global change on the historical trends of water resources in the headwaters of the Llobregat and Ter river basins (Catalonia, Spain). Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2011, 36, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón Porcel, G.; Espín Sánchez, D.; Ruiz Álvarez, V.; García Marín, R.; Moreno Muñoz, D. Runoff water as a resource in the Campo de Cartagena (Region of Murcia): Current possibilities for use and benefits. Water 2018, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Bermúdez, F. Los aljibes, una técnica hidráulica de adaptación a la aridez ya la sequía. El Campo de Cartagena. In IV Congreso Nacional de Etnografía Del Campo de Cartagena: La Vivienda y La Arquitectura Tradicional Del Campo de Cartagena; Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena: Cartagena, Spain, 2015; pp. 548–557. [Google Scholar]

- González Blanco, A.; López Bermúdez, F.; Vera Botí, A. Los aljibes en la historia de la cultura: La realización en el Campo de Cartagena. Rev. Murc. Antropol. 2007, 14, 441–478. [Google Scholar]

- López Bermúdez, F. El riego por boquera en agricultura de secano, técnica hidráulica tradicional de lucha contra la desertificación en el sureste ibérico semiárido. In Geoecología, Cambio Ambiental y Paisaje: Homenaje al Profesor José María García Ruiz; Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología: Zaragoza, Spain, 2014; pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Marco Molina, J.A.; Giménez Font, P. Fonts per a la reconstrucció dels sistemes tradicionals de reg amb aigües d’avinguda en rambles del sud-est peninsular. Cuad. Geogr. Univ. València 2024, 1, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, I.; Healey, R. Historical GIS: Structuring, mapping and analyzing geographies of the past. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda Carrasco, R.; Blanco, A.; Pascual-Aguilar, J.A.; De Bustamante, I. La utilización de mapas antiguos en el inventariado de recursos patrimoniales hidráulicos. In Nuevas Perspectivas de la Geomática Aplicadas al Estudio de Los Paisajes y el Patrimonio Hidráulico; Pascual, J.A., De Bustamente, I., Eds.; Centro para el Conocimiento del Paisaje-Civilscape: Castellón, Spain; Instituto Imdea-Agua: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 79–115. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco González, A.; De Bustamante, I.; Pascual Aguilar, J.A. Using old cartography for the inventory of a forgotten heritage: The hydraulic heritage of the Community of Madrid. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 665, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morote Seguido, Á.F. El aprovechamiento de turbias en San Vicente del Raspeig (Alicante) como ejemplo de sistema de riego tradicional y sostenible. Investig. Geográficas 2013, 59, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarinos Tordera, F.F. La molinería hidráulica eldense. Los martinetes de picar esparto (Siglos XVIII-XIX). In El Mundo Del Agua, Paisaje de Vida: Patrimonio Histórico-Cultural Del Vinalopó; Ayuntamiento de Elda: Elda, Spain, 2018; pp. 101–132. [Google Scholar]

- Marco Molina, J.A.; Giménez Font, P.; Prieto Cerdán, A. Aprovechamiento tradicional de las aguas de avenida y transformaciones de los sistemas fluviales del sureste de la Península Ibérica: La rambla de Abanilla-Benferri. Cuad. Geogr. 2021, 107, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón Porcel, G. Aceñas del Campo de Cartagena (Región de Murcia) representadas en los Bosquejos planimétricos (1898–1901): Identificación, distribución y supervivencia. Cuad. Geográficos 2025, 64, 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón Porcel, G. Identificación, distribución y supervivencia de los molinos de viento de elevar agua del Campo de Cartagena representados en los Bosquejos planimétricos (1898–1901). Agua Territ. 2025, 28, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. Terra Climate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mays, L.; Antoniou, G.P.; Angelakis, A.N. History of water cisterns: Legacies and lessons. Water 2013, 5, 1916–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancomunidad de Canales del Taibilla (MCT). La Mancomunidad de Canales Del Taibilla; MCT: Murcia, Spain, 2018.

- Ramallo Asensio, S.; Ros Sala, M. Villa romana en Balsapintada (Valladolises, Murcia). An. Prehist. Arqueol. 1988, 4, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Castejón Porcel, G. El Paludismo en Fuente Álamo de Murcia y su Erradicación Mediante el Empleo de Galerías Con Lumbreras (ss. XVIII-XIX): Del Riesgo Natural, a la Transformación Agrícola y el Recurso Patrimonial. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 30 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- García Blánquez, L.A. Aprovisionamiento hidráulico romano en el Ager Carthaginensis. Estructuras hidráulicas de almacenaje y depuración. An. Prehist. Arqueol. 2009–2010, 25–26, 213–256. [Google Scholar]

- Woolway, R.I.; Merchant, C.J.; Van Den Hoek, J.; Azorín Molina, C.; Nõges, P.; Laas, A.; Mackay, E.B.; Jones, I.D. Northern Hemisphere atmospheric stilling accelerates lake thermal responses to a warming world. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 11983–11992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente Serrano, S.M.; Azorín Molina, C.; Sánchez Lorenzo, A.; Morán Tejeda, E.; Lorenzo Lacruz, J.; Revuelto, J.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Espejo, F. Temporal evolution of surface humidity in Spain: Recent trends and possible physical mechanisms. Clim. Dyn. 2014, 42, 2655–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente Serrano, S.M.; Domínguez Castro, F.; Murphy, C.; Hannaford, J.; Reig, F.; Peña-Gallardo, M.; Tramblay, Y.; Trigo, R.M.; MacDonald, N.; Luna, M.Y.; et al. Long-term variability and trends in meteorological droughts in Western Europe (1851–2018). Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 4792–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo Lacruz, J.; Morán Tejeda, E.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; López-Moreno, J.I. Streamflow droughts in the Iberian Peninsula between 1945 and 2012: Spatial and temporal patterns. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco Muñoz, J.F.; Aznar Sánchez, J.A.; Batllesde la Fuente, A.; Fidelibus, M.D. Rainwater Harvesting for Agricultural Irrigation: An Analysis of Global Research. Water 2019, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Hernández, M.; Sauri, D.; Moltó Mantero, E. Las aguas pluviales y de tormenta: Del abandono de un recurso hídrico con finalidad agrícola a su implantación como recurso no convencional en ámbitos urbanos. In Paisaje, Cultura Territorial y Vivencia de la Geografía. Libro Homenaje al Profesor Alfredo Morales Gil; Vera, J.F., Olcina, J., Hernández, M., Eds.; Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2016; pp. 1099–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Motsi, K.E.; Chuma, E.; Mukamuri, B.B. Rainwater harvesting for sustainable agriculture in communal lands of Zimbabwe. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2004, 29, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box Amorós, M. Un aprovisionamiento tradicional de agua en el sureste ibérico: Los aljibes. Investig. Geográficas 1995, 13, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Oweis, T.; Salkini, A.B.; El-Naggar, S. Rainwater Cisterns. Traditional Technologies for Dry Areas; International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA): Aleppo, Syria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.; García-Martín, M.; Plieninger, T. Recognizing indigenous farming practices for sustainability: A narrative analysis of key elements and drivers in a Chinese dryland terrace system. Ecosyst. People 2021, 17, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas Borja, M.E. El riego tradicional de cultivos agrícolas ubicados en climas áridos y semiáridos mediante boqueras. In Arida Cutis: Ecología y Retos de Las Zonas Áridas En Un Mundo Cambiante; Martínez, J., Soliveres, S., Maestre, F., Eds.; ADN, Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2024; pp. 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Meseguer, E. Aprovechamientos de escorrentías superficiales eventuales y de subálveos en la rambla de Oria-Albox (Almería). In Paisaje, Cultura Territorial y Vivencia de la Geografía. Libro Homenaje al Profesor Alfredo Morales Gil; Vera, J.F., Olcina, J., Hernández, M., Eds.; Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2016; pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Hernández, M.; Morales Gil, A. Los aprovechamientos tradicionales de las aguas de turbias en los piedemontes del sureste de la Península Ibérica: Estado actual en tierras alicantinas. Boletín Asoc. Española Geogr. 2013, 63, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Gil, A. Aprovechamiento de aguas turbias. In La Cultura Del Agua en la Cuenca Del Segura; CajaMurcia: Murcia, Spain, 2004; pp. 402–438. [Google Scholar]

- Mondéjar Sánchez, J.M. El Riego de Boqueras. Una Técnica Hidráulica Para la Gestión Ambiental de Territorios Semiáridos y Lucha Contra la Desertificación: Aprovechamientos Tradicionales de Aguas de Escorrentía en las Cuencas de la Comarca De l’Alacantí. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 10 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fansa Saleh, G. Gestión Tradicional Del Agua en Ámbitos Áridos y Semiáridos Del Levante Español y Túnez: Análisis Comparado. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 25 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fansa, G.; Pérez Cueva, A.J. Sistemas de aprovechamiento de escorrentía concentrada en conos de deyección: El mgoud de Belkhir (Gafsa, Túnez). In A Vicenç M. Rosselló, M. Geògraf, Alsseus 90 Anys; Mateu, J.F., Furió, A., Eds.; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2021; pp. 419–436. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, S. Soil types and degradation pathways in Saudi Arabia: A geospatial approach for sustainable land management. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wolka, K.; Mulder, J.; Biazin, B. Effects of soil and water conservation techniques on crop yield, runoff and soil loss in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 207, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wei, W.; Chen, L. Effects of terracing practices on water erosion control in China: A metaanalysis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 173, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Nie, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhu, D. Advantages and disadvantages of terracing: A comprehensive review. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021, 9, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Chen, D.; Wang, L.; Daryanto, S.; Chen, L.; Yu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, G.; Feng, T. Global synthesis of the classifications, distributions, benefits and issues of terracing. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 159, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Feng, X.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.; Feng, T.; Chen, D. The effects of terracing and vegetation on soil moisture retention in a dry hilly catchment in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morbidelli, R.; Saltalippi, C.; Flammini, A.; Govindaraju, R.S. Role of slope on infiltration: A review. J. Hydrol. 2018, 557, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Talha, M.; Shah, A.; Khokhar, S.A.; Khan, M.H.; Khushnood, R.A.; Ahmed, T. Advanced structural interventions for slope stabilization and disaster resilience. Discov. Geosci. 2025, 3, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Kaur, R.; Singh, G.; Singh, N. Sustainable Dryland Farming Practices for a Changing Climate. Adv. Agric. Sci. 2025, 49, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Qamar, R.; Ashraf, S.; Tanzeel, F.; Rashad, H.M.; Ather, M.; Atique-ur-Rehman; Yaseen, M.; Saleem, M.; Ahmad, N.; Abbas, T.; et al. Terrace Farming for Better Water Management in Agriculture. In Innovations in Agricultural Water Management; Mubeen, M., Jatoi, W.N., Hashmi, M.Z., Ahmad, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Brimblecombe, P. Climate Pressures on Intangible Heritage. Heritage 2025, 8, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, N. Changing climate; changing life—Climate change and indigenous intangible cultural heritage. Laws 2022, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.E. Changing climate, changing culture: Adding the climate change dimension to the protection of intangible cultural heritage. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2011, 18, 259–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Díaz, A.; Caballero-Pedraza, A.; Pérez-Morales, A. Expansión urbana y turismo en la Comarca del Campo de Cartagena-Mar Menor (Murcia). Impacto en el sellado del suelo. Cuad. Tur. 2017, 39, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo Marín, C.; Aparicio Guerrero, A. La producción de electricidad con energía solar fotovoltaica en España en el Siglo XXI. Rev. Estud. Andal. 2020, 39, 66–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo Lacruz, J.; Morán Tejeda, E.; Vicente Serrano, S.M.; López Moreno, J.I. Streamflow droughts in the Iberian Peninsula between 1945 and 2005: Spatial and temporal patterns. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeste, P.; Dorador, J.; Molero, E.; Martín-Rosales, W.; Esteban-Parra, M.J. Climate-driven trends in the streamflow records of a reference hydrologic network in Southern Spain. J. Hydrol. 2019, 578, 124047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coch, A.; Jiménez Cárcel, O.; Buendía, C. Trends in low flows in Spain in the period 1949–2009. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016, 61, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellin, N.; Van Wesemael, B.; Meerkerk, A.; Vanacker, V.; Barbera, G.G. Abandonment of soil and water conservation structures in Mediterranean ecosystems: A case study from southeast Spain. Catena 2009, 76, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyonarte, N.A.; Gómez-Macpherson, H.; Martos Rosillo, S.; González-Ramón, A.; Mateos, L. Revisiting irrigation efficiency before restoring ancient irrigation systems in Spain. Agric. Syst. 2022, 203, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Ackermann, O.; Terol, E.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Impact of Farmland Abandonment on Water Resources and Soil Conservation in Citrus Plantations in Eastern Spain. Water 2019, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level 1 CLC | 1990 (ha) | 2000 (ha) | 2018 (ha) | Difference | Variation Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial surfaces | 7719.8 | 10,260.6 | 16,405.7 | 8685.9 | 112.5 |

| Agricultural areas | 126,189.7 | 130,046.0 | 130,590.4 | 4400.7 | 3.5 |

| Plant areas with natural vegetation and open spaces | 49,671.8 | 47,261.8 | 44,343.5 | −5328.3 | −10.7 |

| Wetland areas | 974.9 | 938.0 | 730.8 | −244.1 | −25.0 |

| Water surfaces * | 13,502.1 | 13,502.2 | 13,465.1 | −37.0 | −0.3 |

| Id—Level 3 CLC | CODE 90 | 1990 | 2000 | 2018 | TV% | Difference 1990–2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous urban fabric | 111 | 2925.6 | 3263.0 | 4301.4 | 47.0 | 1375.8 |

| Discontinuous urban fabric | 112 | 2046.0 | 3094.6 | 2987.2 | 46.0 | 941.3 |

| Industrial and commercial zones | 121 | 534.0 | 1247.6 | 3072.5 | 475.4 | 2538.5 |

| Road and rail networks | 122 | - | - | 214.3 | - | 214.3 |

| Port areas | 123 | 25.3 | 282.0 | 225.9 | −9.7 | −24.4 |

| Airports | 124 | 128.2 | 128.2 | 663.5 | 417.5 | 535.3 |

| Mining extraction areas | 131 | 693.4 | 782.3 | 1506.1 | 117.2 | 812.7 |

| Landfills and dumps | 132 | 754.4 | 780.5 | 404.2 | −46.4 | −350.2 |

| Construction areas | 133 | 229.9 | 373.9 | 433.8 | 88.7 | 203.9 |

| Green urban zones | 141 | - | 31.5 | 75.8 | - | 75.8 |

| Sports and recreational zones | 142 | 157.9 | 276.9 | 2520.9 | 1496.0 | 2362.9 |

| Dry farmland | 211 | 26,031.9 | 11,688.3 | 3874.7 | −85.1 | −22,157.2 |

| Permanently irrigated lands | 212 | 36,985.9 | 48,441.7 | 55,830.7 | 51.0 | 18,844.8 |

| Vineyards | 221 | - | 160.2 | 217.1 | 35.5 | 217.1 |

| Fruit trees | 222 | 32,245.4 | 41,501.6 | 50,394.6 | 56.3 | 18,149.2 |

| Olive trees | 223 | 372.3 | 103.5 | 407.0 | 9.3 | 34.7 |

| Grasslands | 231 | - | - | 6729.9 | - | 6729.9 |

| Annual crops with permanent crops | 241 | 30.8 | 30.8 | - | −100.0 | −30.8 |

| Cropmosaic | 242 | 24,704.3 | 23,577.3 | 10,889.6 | −55.9 | −13,814.7 |

| Mainly agricultural land | 243 | 5819.2 | 4542.6 | 2246.8 | −61.4 | −3572.4 |

| Coniferous forest | 312 | 8072.9 | 8076.0 | 11,976.3 | 48,4 | 3903.4 |

| Mixed forest | 313 | 231.7 | 231.7 | - | −100,0 | −231.7 |

| Natural grasslands | 321 | - | 80.3 | 11,140.3 | - | 11,140.3 |

| Sclerophyllous vegetation | 323 | 23,770.9 | 22,819.6 | 18,257.6 | −23.2 | −5513.3 |

| Transitional woodland scrub | 324 | 7272.6 | 7034.5 | 2534.7 | −65.1 | −4737.8 |

| Beaches, dunes and sandy areas | 331 | 1329.2 | 1,272.4 | 95.1 | −92.8 | −1234.2 |

| Rock areas | 332 | - | - | 26.0 | - | 26.0 |

| Spaces with sparse vegetation | 333 | 8994.6 | 7747.5 | 313.6 | −96.5 | −8681.0 |

| Marshes | 421 | 211.0 | 174.1 | - | −100.0 | −211.0 |

| Salt marsh | 422 | 629.1 | 629.1 | 597.6 | −5.0 | −31.6 |

| Intertidal flats | 423 | 134.9 | 134.9 | 133.2 | −1.2 | −1.6 |

| Sheets of water | 512 | - | - | 49.5 | - | 49.5 |

| Coastal lagoons | 521 | 13,502.1 | 13,502.2 | 13,415.5 | −0.6 | −86.6 |

| TOTAL | 184,556.3 | 188,506.5 | 192,070.4 | 4.1 | 7514.100 |

| Trend/dec | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PET | DJF | 0.70 | 0.079 |

| MAM | 3.54 ** | 0.000 | |

| JJA | 5.97 ** | 0.000 | |

| SON | 2.09 ** | 0.000 | |

| ANN | 12.13 ** | 0.000 | |

| Q | DJF | −0.07 | 0.054 |

| MAM | 0.18 | 0.139 | |

| JJA | −0.04 * | 0.003 | |

| SON | −0.09 | 0.472 | |

| ANN | −0.01 | 0.906 | |

| PPT | DJF | −4.05 * | 0.048 |

| MAM | 2.29 | 0.430 | |

| JJA | −2.74 * | 0.002 | |

| SON | 0.00 | 0.998 | |

| ANN | −4.32 | 0.348 | |

| TMAX | DJF | 0.19 ** | 0.000 |

| MAM | 0.24 ** | 0.000 | |

| JJA | 0.40 ** | 0.000 | |

| SON | 0.26 ** | 0.000 | |

| ANN | 0.27 ** | 0.000 | |

| TMIN | DJF | 0.12 | 0.055 |

| MAM | 0.27 ** | 0.000 | |

| JJA | 0.40 ** | 0.000 | |

| SON | 0.27 ** | 0.000 | |

| ANN | 0.26 ** | 0.000 | |

| SPEI−12 | DJF | −0.18 * | 0.003 |

| MAM | −0.19 * | 0.001 | |

| JJA | −0.19 * | 0.002 | |

| SON | −0.17 * | 0.003 | |

| ANN | −0.17 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Castejón-Porcel, G.; Espín-Sánchez, D.; García-Marín, R. Global Change: Impacts on Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Systems in Campo de Cartagena (Region of Murcia, Spain). Land 2026, 15, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010098

Castejón-Porcel G, Espín-Sánchez D, García-Marín R. Global Change: Impacts on Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Systems in Campo de Cartagena (Region of Murcia, Spain). Land. 2026; 15(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastejón-Porcel, Gregorio, David Espín-Sánchez, and Ramón García-Marín. 2026. "Global Change: Impacts on Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Systems in Campo de Cartagena (Region of Murcia, Spain)" Land 15, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010098

APA StyleCastejón-Porcel, G., Espín-Sánchez, D., & García-Marín, R. (2026). Global Change: Impacts on Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Systems in Campo de Cartagena (Region of Murcia, Spain). Land, 15(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010098