1. Introduction

The global economy is undergoing a profound transformation driven by technological revolution and industrial restructuring [

1]. Within this context, China has proposed the strategic concept of new quality productivity (NQP), an advanced productivity paradigm formally introduced in late 2023 [

2,

3]. Characterized by high technology, efficiency, and quality standards, NQP represents an innovation-driven approach aimed at achieving substantial total factor productivity gains [

4,

5]. This paradigm marks a fundamental departure from traditional factor-driven growth models, recalibrating economic development logic and necessitating novel approaches to production factor allocation.

As the essential spatial carrier for production factors, land plays a pivotal role in the cultivation and materialization of NQP [

6]. Theoretically, optimized land resource allocation can act as a catalyst, initiating cross-factor reforms and unlocking compounded effects among various production inputs [

7,

8], while the infusion of digital technologies and advanced knowledge propels land use patterns toward intensive, high-value-added activities [

9,

10]. Concurrently, land use efficiency (LUE) serves as a crucial indicator for assessing the coordination between socioeconomic development and ecological sustainability [

11,

12,

13]. The synergy between NQP’s sustainable development principles and LUE’s pursuit of economic, social, and environmental benefits [

14,

15,

16] underscores the critical importance of investigating their intrinsic linkage for fostering high-quality, sustainable economic development.

Despite the strategic importance, rigorous empirical research on the NQP-LUE nexus remains nascent. Existing literature can be broadly categorized into three streams. The first focuses on conceptualizing NQP itself, delving into its theoretical origins [

3], scientific connotation [

17,

18], and strategic value [

19,

20,

21], thereby laying a preliminary foundation for its conceptual edifice. A second, emerging stream of cross-disciplinary inquiry has begun to interrogate the relationship between land elements and productivity evolution under this new framework. Scholars posit that land is no longer a passive factor but an active platform integrating innovation [

22]. For instance, Liu et al. [

23] theorized that land resource allocation influences productivity efficiency primarily through three channels: industrial structure adjustment, technological innovation incentives, and ecological environment amelioration. Yu et al. [

24] further contextualized this relationship by examining the co-evolution of NQP development and land resource allocation through historical, theoretical, and contemporary pragmatic lenses. Complementarily, studies also highlight the inverse constraint. Land resource misallocation—such as excessive allocation to low-efficiency traditional industries or disordered urban sprawl—significantly constrains the quality of urban economic development [

7,

25], thereby inhibiting the accumulation of innovation factors and impeding regional NQP cultivation. However, a third stream—rigorous quantitative empirical testing of the NQP-LUE relationship—is conspicuously underdeveloped, with extant work leaning heavily towards qualitative exposition [

6,

23,

24,

26].

Consequently, significant research gaps persist: (1) A lack of a systematic, context-specific quantitative assessment framework for NQP. While some studies have attempted to measure NQP, a systematic and widely recognized evaluation framework applicable to land use contexts is still lacking. (2) An unclear “black box” regarding the precise transmission mechanisms (e.g., technological progress, factor allocation) through which NQP influences LUE. (3) Insufficient exploration of the spatial and conditional heterogeneity of this impact. It is plausible that the impact of NQP on LUE varies significantly across regions with different economic development levels, city sizes, or resource endowments (e.g., arable land resources). However, this spatial and conditional heterogeneity has received scant attention, limiting the generalizability of findings and the formulation of targeted, place-based policies.

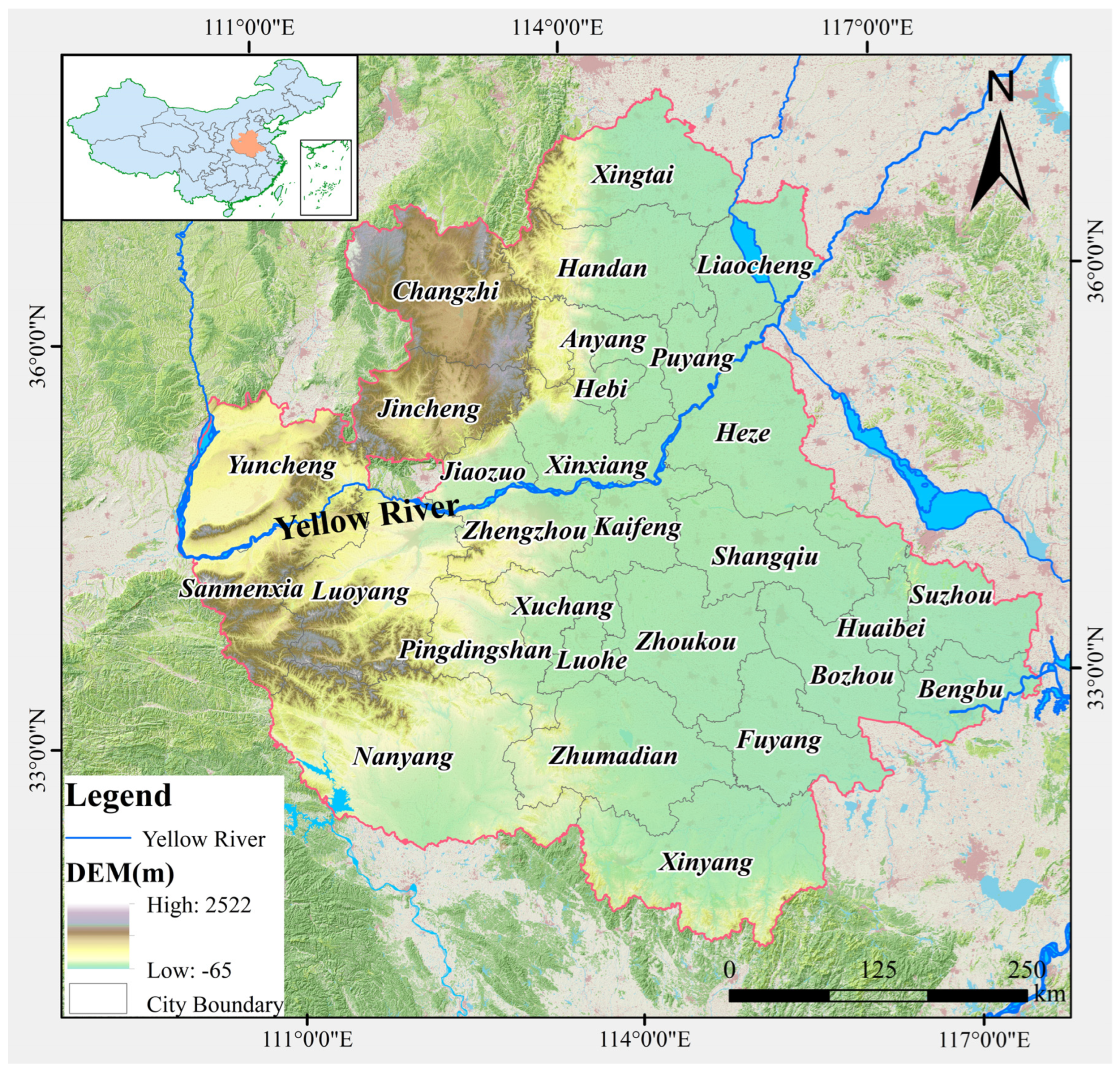

The Central Plains Urban Agglomeration (CPUA) presents an ideal empirical setting to address these research gaps. Situated in China’s strategic inland hinterland, the CPUA serves as a vital economic nexus and a testing ground for national regional development strategies. Characterized by a midtier level of economic development nationally, the CPUA embodies the classic dual challenge faced by many developing regions: the imperative to accelerate economic growth while simultaneously ensuring sustainable land resource management and efficiency enhancement [

27,

28]. In an era of rapid urbanization, the escalating demand for land resources intensifies the tension between growth objectives and resource constraints [

29,

30]. Within this context, reconciling the advancement of NQP with the enhancement of LUE emerges as a pressing and complex issue demanding immediate scholarly and policy focus.

To bridge these critical gaps, the primary objective of this study is to empirically investigate the impact mechanism of NQP on LUE within the CPUA and to unravel the heterogeneity of this relationship. Compared to previous studies, this research offers distinct advantages and innovations: (1) Methodologically, it integrates the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, super-efficiency SBM model, Malmquist index, and fixed-effects models to construct a comprehensive “measurement–evolution–mechanism–heterogeneity” analytical chain, enabling a more rigorous and multi-faceted test of the NQP-LUE nexus. (2) In terms of content, it moves beyond theoretical postulation to provide the first empirical validation of the NQP-LUE relationship in the CPUA, explicitly tests technological progress as a key mediating pathway, and systematically examines heterogeneity based on city scale, arable land endowment, and economic development level. (3) From a geographical perspective, it focuses on a strategically important yet underexplored urban agglomeration, offering place-based insights that complement studies focused on coastal or more developed regions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 elaborates the theoretical analysis and research hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the study area and data sources.

Section 4 details the methodology and indicator systems.

Section 5 presents the empirical results, including spatiotemporal evolution, impact mechanisms, and heterogeneity analysis.

Section 6 discusses the findings in relation to existing literature. Finally,

Section 7 presents the conclusions and policy implications, and discusses research limitations along with future directions.

The findings of this study are expected to bridge the critical gap between theoretical postulation and empirical evidence regarding the NQP-LUE nexus. By clarifying the impact mechanisms and conditional heterogeneities, this research will provide a robust empirical foundation and actionable insights for optimizing land resource allocation and fostering targeted NQP development within the CPUA and other comparable regions, thereby supporting their transition toward sustainable and high-quality development trajectories.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses

As an advanced productivity paradigm centered on innovation, new quality productivity (NQP) fundamentally reshapes the input–output dynamics of production factors, thereby establishing a profound theoretical connection with land use efficiency (LUE). Within the framework of Chinese-style modernization, where sustainable development is paramount, the efficient allocation of the finite resource of land becomes critically important [

24]. NQP, with technological innovation as its core driver, recalibrates the allocation mechanisms of production factors and propels industrial transformation and upgrading [

11,

31]. This process offers a novel theoretical lens and actionable pathways for understanding and enhancing LUE. Grounded in the intrinsic linkage between NQP and LUE, this study proposes the following hypotheses to systematically investigate the impact relationship, transmission mechanisms, and underlying heterogeneity.

H1. NQP exerts a significant positive influence on LUE.

The proposed positive impact of NQP on LUE is theorized to operate through three interconnected mechanisms, forming the core of our analytical framework:

- (a)

Factor configuration optimization through agglomeration economies. NQP, characterized by the integration of high-end knowledge, advanced technology, and data, transcends traditional factor inputs subject to diminishing returns. It fosters synergistic interactions among these advanced factors, which tend to geographically agglomerate in innovation hubs. This agglomeration reduces transaction costs, accelerates knowledge spillovers, and enables more efficient matching of factor inputs—including land—to their most productive uses. Consequently, the land input–output relationship is reconfigured, elevating output per unit of land area.

- (b)

Technological permeation and empowerment mitigating spatial mismatch. At the technological level, advancements such as Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, and the Internet of Things enable the development of smart land management systems. These technologies address classic spatial mismatch problems by improving information flows and analytical capabilities. They facilitate precise matching of land supply and demand, mitigate allocation distortions stemming from information asymmetry, and support data-driven decision-making. This technological empowerment directly reduces land idling and misuse, thereby enhancing utilization precision and overall efficiency.

- (c)

Industrial structure transformation and upgrading guided by locational advantage. NQP drives industries toward high-end, intelligent, and green development. This shift embodies a structural transformation of the regional economy. Land resources are progressively reallocated from low-value-added, extensive-use sectors to high-value-added, intensive-use sectors that benefit from or even require proximity to NQP clusters (e.g., R&D centers, advanced manufacturing). This process optimizes the spatial structure of land use in accordance with evolving regional comparative advantages, lifting aggregate land use efficiency.

H2. Technological progress serves as a primary transmission pathway through which NQP enhances LUE.

Technological progress is the hallmark of NQP and is posited as a central channel mediating its effect on LUE. This mediation manifests in several key areas:

- (a)

Land management and decision-making. The application of smart land management systems, leveraging cloud computing and Internet of Things, allows for real-time monitoring and sophisticated analysis of land resource data. This provides a scientific foundation for land-use planning and management, minimizing inefficiencies and errors in decision-making that lead to land waste.

- (b)

Production process transformation. Technological progress revolutionizes production methods across sectors. In industry, intelligent manufacturing and automation increase production efficiency while reducing the consumption of land and other inputs per unit of output. In agriculture, modern planting techniques and precision farming enhance crop yields and land productivity.

- (c)

Industrial structure facilitation. As a key driver of industrial upgrading, technological innovation catalyzes the emergence of new industries and the high-end transformation of traditional ones. This guides land resources toward more efficient and productive sectors, optimizing the macro-level structure of land use and ultimately boosting overall LUE.

Synthesizing the aforementioned analysis, the postulated mechanism underlying the effect of new quality productivity on land use efficiency is graphically summarized in

Figure 1.

5. Results

5.1. Spatiotemporal Evolution of NQP

To elucidate the spatial differentiation patterns of new quality productivity (NQP) within the Central Plains Urban Agglomeration (CPUA), we employed the natural breaks classification method in ArcGIS 10.8 to categorize NQP levels into five distinct tiers. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the NQP development in the CPUA demonstrated pronounced temporal phasing and spatial heterogeneity during the 2010–2023 period. The composite NQP index exhibited a “stepwise growth” trajectory, ascending from 0.280 to 0.828 with an average annual growth rate of 6.5%, reflecting the region’s progressive transition toward innovation-driven development.

The evolutionary process unfolded through two distinctive phases characterized by different growth dynamics. The initial accumulation phase (2010–2015) witnessed moderate growth at 4.2% annually, during which Zhengzhou emerged as an early innovation pole leveraging its provincial capital advantages. The city’s NQP index increased from 0.280 to 0.363, representing a 29.6% growth that substantially exceeded the regional average. The subsequent acceleration phase (2016–2023) saw enhanced policy support and innovation ecosystem development, propelling Zhengzhou’s NQP index to 0.828 through 9.8% annual growth—a 128.1% increase from 2015. This established a “unipolar leadership” pattern that stimulated catch-up development in secondary cities like Luoyang and Nanyang, consequently elevating the regional growth rate to 8.1%.

Spatially, the NQP distribution revealed a clearly defined core–secondary–periphery gradient structure, indicating the presence of hierarchical diffusion mechanisms. The core growth pole centered on Zhengzhou (NQP index: 0.828 in 2023) demonstrated superior performance in high-end talent concentration, technology enterprise agglomeration, and policy resource acquisition. Its leading position was further reinforced by rapid expansion in emerging industries including digital economy and biomedicine, establishing it as the primary regional innovation radiation source. The secondary coordination zone, represented by Luoyang (0.310) and Nanyang (0.234), developed differentiated innovation pathways through intelligent upgrading of equipment manufacturing and technological breakthroughs in cultural-tourism integration and agricultural product processing, respectively. Achieving annual growth rates of 7.3% and 6.8%, these cities formed complementary industrial synergies with the core region, facilitating knowledge spillovers and industrial chain integration. The peripheral development zone, encompassing cities such as Handan, Jincheng, and Bengbu, generally registered NQP levels below 0.2, indicating significant development gaps. Particularly, Hebi (0.126) and Bozhou (0.124) remained constrained by resource-dependent economic structures, exhibiting insufficient innovation investment and inefficient factor allocation that hindered their NQP development trajectories.

5.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution of LUE

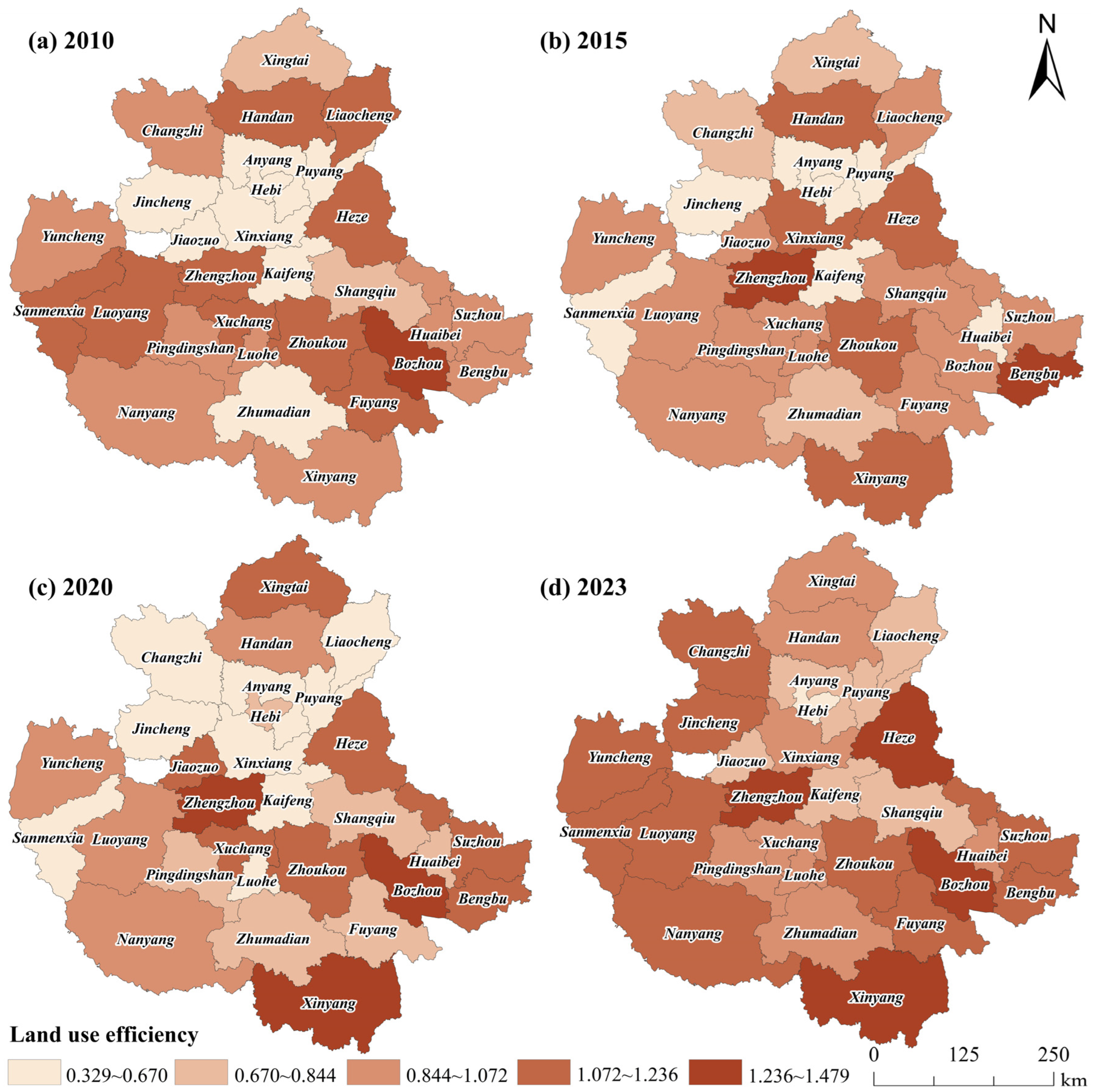

Figure 4 illustrates the spatiotemporal dynamics of land use efficiency (LEU) within the CPUA during the 2010–2023 period. Temporally, the region demonstrated a consistent upward trajectory in land use efficiency, with the mean efficiency value increasing from 0.917 to 1.031, corresponding to an average annual growth rate of 1.0%. This progressive enhancement reflects the ongoing transition toward intensive and sustainable land use patterns across the urban agglomeration.

Specifically, notable inter-city disparities emerged in the efficiency patterns. Zhengzhou maintained a dominant position with the highest mean efficiency score of 1.388, a position attributable to its strategic advantages as a provincial capital, including superior resource allocation capabilities, robust economic growth dynamics, and advanced land intensification practices. Conversely, Kaifeng registered the lowest efficiency level at 0.53, constrained by structural limitations in industrial development and suboptimal land utilization intensity. While most cities demonstrated efficiency scores within the 0.5–1.2 range, several municipalities—notably Bozhou and Bengbu—achieved commendable performance through synergistic combinations of economic vitality and optimized land resource management.

Spatially, the distribution patterns exhibit distinct provincial-level characteristics. Cities within Henan Province consistently outperformed their counterparts, with Zhengzhou, Xuchang, Xinyang, and Nanyang forming a high-efficiency cluster. This spatial advantage stems from Henan’s integrated economic ecosystem, characterized by substantial scale economies, rapid urbanization, and mature industrial transformation. In contrast, Hebei-based cities including Handan, Xingtai, and Liaocheng displayed relative inefficiency, primarily impeded by structural rigidities in industrial composition and conventional land use paradigms. The mixed performance observed in Shanxi (Jincheng, Changzhi, Yuncheng) and Anhui (Bengbu, Bozhou, Huaibei) reflects the complex interplay of local socioeconomic conditions and governance frameworks.

5.3. Dynamic Evolution Characteristics of LUE

While the super-efficiency SBM model effectively measures static LUE values for cities in the CPUA, it possesses inherent limitations in capturing efficiency dynamics. To address this gap and systematically examine the evolutionary characteristics of urban land use efficiency, this study employs MaxDEA Ultra 12.0 software to calculate the Malmquist productivity indices for 2010–2023, thereby providing deeper insights into the dynamic changes in LUE across the region.

As delineated in

Table 3, 65.52% of cities exhibited growth in comprehensive technical efficiency during the study period, with an average annual growth rate of 1.7%. Puyang, Xinxiang, and Jincheng demonstrated the most rapid growth at 15.0%, 14.8%, and 12.1%, respectively. Technological progress emerged as the primary driver of efficiency improvement, registering an impressive annual growth rate of 14.3%. Notably, all 29 cities achieved total factor productivity (TFP) indices exceeding 1, confirming an overall dynamic growth trajectory in land use efficiency across the urban agglomeration. The scale efficiency analysis reveals that 79.3% of cities maintained scale efficiency indices above 1, indicating successful transition from input surplus conditions and demonstrating positive scale effects that significantly contributed to comprehensive technical efficiency growth. Conversely, the remaining 21.7% of cities exhibited scale efficiency indices below 1, suggesting suboptimal input scales that necessitate fundamental shifts from extensive utilization patterns toward intensive land use through optimized input scaling. Pure technical efficiency showed an annual growth rate of 3.2%, though six cities—Luoyang, Xuchang, Anyang, Zhoukou, Handan, and Xingtai—displayed declining trends. This pattern indicates inadequate utilization of existing technological capacities in these municipalities, resulting in substantial input–output redundancies that require enhanced economic output generation and reduced undesirable outputs.

Based on the decomposed Malmquist indices presented in

Table 4, the TFP for land use in the CPUA consistently exceeded 1 throughout 2010–2023, achieving an impressive annual growth rate of 16.4%. Technological progress, with its 14.3% annual growth rate, constituted the dominant driving force, thus validating research hypothesis H2. The complementary 4.1% growth in comprehensive technical efficiency reveals a distinctive “technology-led, efficiency-coordinated” development pattern, while simultaneously indicating significant potential for further optimization in resource allocation and management efficiency—a finding consistent with Song et al.’s [

50] research.

Temporal analysis reveals substantial fluctuations in TFP growth. The modest 0.9% increase during 2014–2015 likely reflects broader economic slowdown and industrial restructuring delays [

51], while the remarkable 48.4% surge in 2020–2021 can be attributed to concentrated implementation of innovation policies and post-pandemic productivity recovery. Furthermore, scale efficiency indices demonstrated declining trends across six specific time nodes (2010, 2011, 2013, 2017, 2021, and 2022), indicating gradually weakening alignment between input scale and output effectiveness. This scale inefficiency consequently constrained comprehensive technical efficiency improvement, particularly evident in cities like Handan and Xingtai where land expansion-dependent development models remain prevalent.

5.4. Impact Mechanism Analysis

5.4.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

This study employs a fixed-effects model to examine the impact of NQP on LUE, with results presented in

Table 5. All specifications include year fixed and city fixed effects, while control variables are sequentially added to test the robustness of the findings. The baseline specification [Column (1)] incorporating only GDP and technology investment shows a statistically significant coefficient of 0.760 for NQP (

p < 0.05), providing preliminary evidence of its positive effect. As additional controls for technology investment, government intervention, population size, and cultivated land area are incrementally included [Columns (2)–(5)], the NQP coefficients increase to 0.770, 0.873, 0.860, and 1.009, respectively, all significant at the 1% level. The fully specified model [Column (6)] yields a NQP coefficient of 1.178, maintaining 1% statistical significance. These results demonstrate that NQP development significantly enhances land use efficiency after controlling for economic scale, technological inputs, and policy interventions. The consistent positive relationship across different model specifications confirms the robust association between the core explanatory variable and the outcome measure.

5.4.2. Heterogeneity Regression Analysis

Given the established positive relationship between NQP and LUE, we further investigate potential heterogeneous effects across cities with different economic scales, cultivated land endowments, and development levels. Using mean values of GDP, cultivated land area, and per capita GDP as grouping thresholds, we conduct subgroup analyses on 29 sample cities (

Table 6). The results reveal significant urban characteristics in the NQP-LUE relationship.

For city scale heterogeneity, large cities exhibit a NQP coefficient of 2.304 (p < 0.01), indicating that urban agglomeration enables NQP to enhance intensive land use through technological spillovers, industrial upgrading, and factor marketization. In contrast, small cities show an insignificant negative coefficient (−3.541), suggesting limited technological absorption capacity and underdeveloped innovation ecosystems constrain NQP’s positive effects.

Regarding cultivated land resource heterogeneity, cities with scarce cultivated land demonstrate a significant positive NQP coefficient of 1.079 (p < 0.1). The underlying mechanism involves land constraints forcing urban spatial transformation toward non-agricultural industries that better align with NQP elements like digital technologies and high-end human capital. Conversely, cities abundant in cultivated land show an insignificant negative coefficient (−0.635), reflecting inadequate synergy between NQP and LUE due to traditional agricultural dependence, single land use structures, and slow technological penetration in agriculture.

Concerning economic development heterogeneity, high-development cities exhibit a positive NQP coefficient of 1.135 (p < 0.1), driven by substantial innovation investment and effective industry–university–research collaboration that facilitate technological transformation and land use structure upgrading. Low-development cities show an insignificant negative coefficient (−3.491), indicating insufficient R&D funding and brain drain hinder the establishment of effective NQP-LUE coordination.

5.4.3. Robustness Test

To test the reliability and stability of the benchmark regression results, this study used the strategies of lagging the explanatory variable by one, two, and three periods to conduct robustness tests.

Table 7 presents the results of these specifications, all of which maintain the same set of control variables and include both year fixed and city fixed effects consistent with our baseline methodology. The empirical evidence demonstrates a persistent yet temporally diminishing effect of NQP on LUE. Specifically, the one-period lag specification [Column (1)] yields a statistically significant coefficient of 0.880 (

p < 0.05), indicating strong short-term persistence. The two-period lag model [Column (2)] produces a coefficient of 0.782 (

p < 0.10), suggesting a moderately sustained medium-term effect. However, the three-period lag specification [Column (3)] shows an insignificant coefficient of 0.192, revealing the temporal boundary of NQP’s influence on LUE.