Ecoparque: An Example of Nature-Based Solutions Implementation at Tijuana a Global South City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Vegetation inventories (species’ richness and abundance, natives, and exotic)

- Water quality (bacteriological, organic, inorganic, and nutrient content)

- Birdwatching (species)

- Compost quality (NPK content)

- Solar energy generation (kwh per time)

- Risk (firewalls, security measures, and number of accidents)

- Environmental education (number of visitors per educational level, workshops, tours, volunteering, and consulting)

2.1. Tijuana’s Urban Context and Challenges

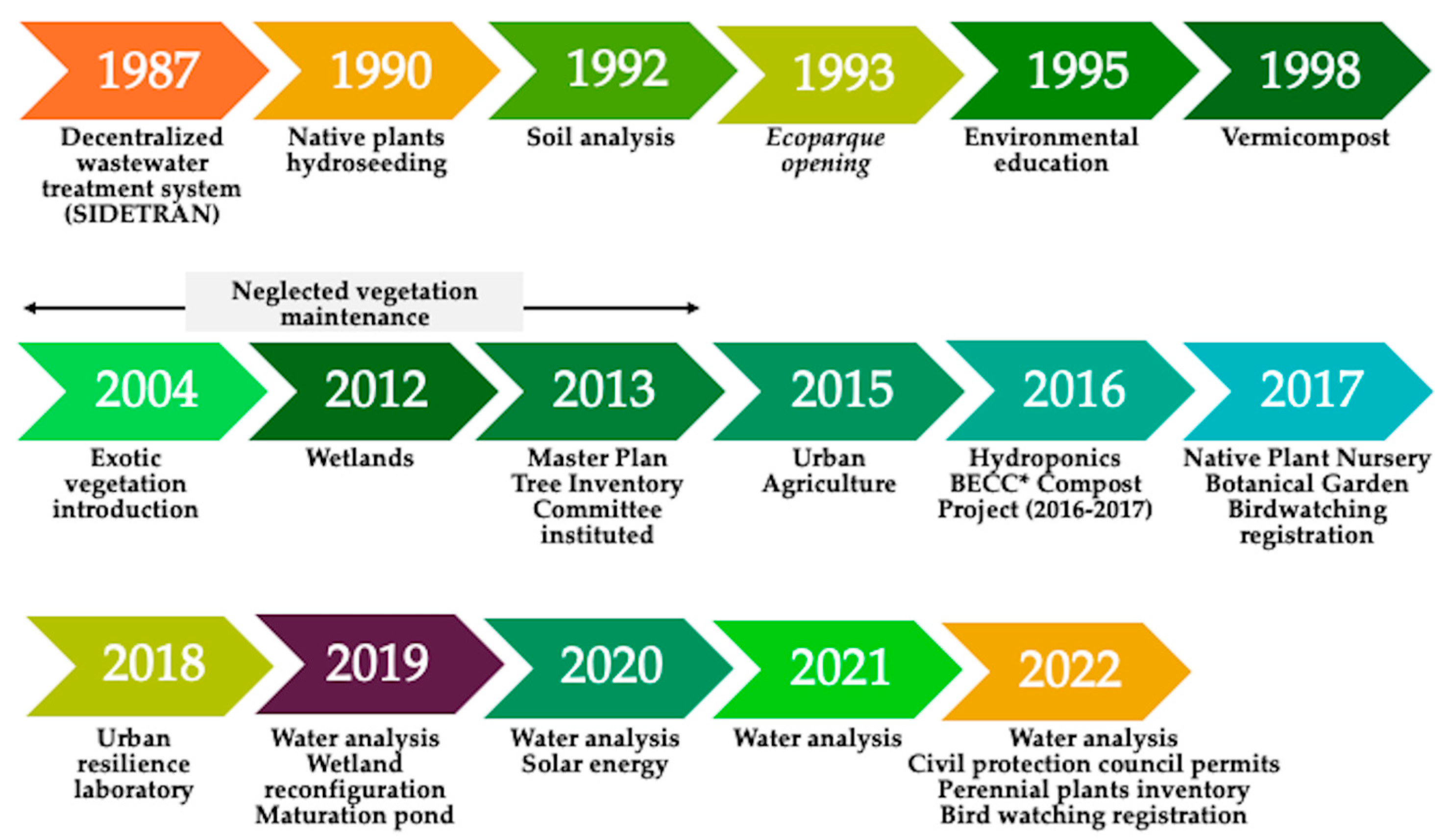

2.2. Ecoparque, an Urban Resilience Laboratory

2.2.1. Constructed Wetlands

- Unit 1. Surface ≈ 533 m2 (width = 13 m, length = 41 m), depth of 0.52 m at 1.06 m (slope 1%)

- Unit 2. Surface ≈ 560 m2 (width = 13 m, length = 43 m), depth of 0.90 m at 1.25 m (slope 1%)

- Water tanks ≈ 60 m2 (width = 5 m, length = 12 m) depth = 2.5 m

2.2.2. Reforestation with Native Plants

2.2.3. Soil Restoration Using Compost and Vermicompost

2.2.4. Ecosystem Restoration

2.2.5. Edible Forest

3. Results as a Summary of Key Experiences and Lessons Learned

4. Discussion on NBS Principles and Challenges at Ecoparque

4.1. General Challenges for NBS in Ecoparque

4.2. During Implementation and Maintenance

- Social preference for lustrous vegetation of humid places

- Quality of residues to be composted

- Household enrolment

- Insufficient funds

- Limited specialized human resources

- Thefts of tools and urban agricultural production

- “Siphon effect at wetland” (vacuum effect)

- Substrate clogging with sediments

- Lack of wastewater inlets due to clogging

- Steep slopes

- Supersaturation of composting piles during the rainy season

- Pest and disease control

- Native species propagation

- Rodents at the composting beds

- Adaptation to local urban and site conditions

- Adaptation of native plants to the urban environment

4.3. Scaling up NBS

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| El Colef | El Colegio de la Frontera Norte |

| CPI | Centro Público de Investigación |

| NBS | Nature-based solutions |

| CA | California |

| USA | United States of America |

| KWh | Kilo Watt hour |

| DEWATs | Decentralized Wastewater Treatment Plant |

| HP | Horse Power |

| SMADS | Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable |

| SEMARNAT | Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales |

| UNPFA | United Nations Population Fund |

| UN-Habitat | United Nations Human Settlements Programme |

| IMPLAN | Instituto Metropolitano de Planeación de Tijuana |

| INEGI | Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística |

| CEABC | Comisión Estatal del Agua de Baja California |

| SPA | Secretaria de Protección al Ambiente |

| SEDEMA | Secretaría del Medio Ambiente |

| SIDETRANS | Sistema Descentralizado de Tratamiento y Reúso de Aguas Negras en Zonas Urbanas |

| LOR | Lina Ojeda-Revah |

| GMM | Gabriela Muñoz-Meléndez |

References

- United Nations Population Fund (UNPFA). Urbanization. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/urbanization (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Cities and Climate Change Action. World Cities Report 2024; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/world-cities-report-2024-cities-and-climate-action (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Yigitcanlara, T.; Kamruzzamanf, M.; Buysb, L.; Giuseppe, I.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; Moreira da Costa, E.; Yune, J.J. Understanding ‘Smart Cities’: Intertwining Development Drivers with Desired Outcomes in a Multidimensional Framework. Cities 2018, 81, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. A Systematic Review of Big Data-Based Urban Sustainability Research: State-of-the-Science and Future Directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 123142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J. Smart Sustainable Cities of the Future: An Extensive Interdisciplinary Literature Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 31, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenar, J.B.; Elliot, T.; Rugani, B.; Philippe, B.; Navarrete Gutierrez, T.; Sonnemann, G.; Geneletti, D. Nexus between Nature-Based Solutions, Ecosystem Services and Urban Challenges. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Brief Me on Nature-Based Solutions. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/biodiversity/brief-me-nature-based-solutions_en (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Albert, C.; Brillinger, M.; Guerrero, P.; Gottwald, S.; Henze, J.; Schmidt, S.; Ott, E.; Schröter, B. Planning Nature-Based Solutions: Principles, Steps, and Insights. Ambio 2021, 50, 1446–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millenium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Andrade, A.; Dalton, J.; Dudley, N.; Jones, M.; Kumar, C.; Maginnis, S.; Maynard, S.; Nelson, C.R.; Renaud, F.G.; et al. Core Principles for Successfully Implementing and Upscaling Nature-Based Solutions. In Environmental Science and Policy; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. IUCN Global Standard for Nature-Based Solution. A User-Friendly Framework for the Verification, Design and Scaling up of NbS; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Hansen, R. Principles for Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Ambio 2022, 51, 1388–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorst, H.; van der Jagt, A.; Toxopeus, H.; Tozer, L.; Raven, R.; Runhaar, H. What’s behind the Barriers? Uncovering Structural Conditions Working against Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2022, 220, 104335–104348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabi, S.; Han, Q.; Romme, A.G.L.; de Vries, B.; Valkenburg, R.; Den Ouden, E.; Zalokar, S.; Wendling, L. Barriers to the Adoption of Urban Living Labs for NbS Implementation: A Systemic Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the Value and Limits of Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change and Other Global Challenges. In Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences; Royal Society Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Duque, L.P.; Trilleras, J.M.; Castellarini, F.; Quijas, S. Ecosystem Services in Urban Ecological Infrastructure of Latin America and the Caribbean: How Do They Contribute to Urban Planning? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojeda-Revah, L.; Ochoa González, Y.; Vera, L. Fragmented Urban Greenspace Planning in Major Mexican Municipalities. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, G.; Wild, T.; Hernandez-Garcia, J.; Baptista, M.D.; van Lierop, M.; Bina, O.; Inch, A.; Ode Sang, Å.; Buijs, A.; Dobbs, C.; et al. Supporting Nature-Based Solutions via Nature-Based Thinking across European and Latin American Cities. Ambio 2024, 53, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozment, S.; Gonzalez, M.; Schumacher, A.; Oliver, E.; Silva, M.; Grunwald, A.; Watson, G. Nature-Based Solutions in Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Status and Priorities for Growth; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications, 6th ed.; AGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Remenyi, D. Case Study Research: The Quick Guide Series; van Zyl, W., Ed.; Research Essentials; UJ Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerring, J. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Metropolitano de Planeación de Tijuana. Programa de Desarrollo Urbano del Centro de Población de Tijuana 2020–2040; Instituto Metropolitano de Planeación de Tijuana: Tijuana, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Rylands, A.B. Biodiversity Hotspots. In Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene: Volumes 1-5; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton-Gonzalez, R.; Mellink, E. One Shared Region and Two Different Change Patterns: Land Use Change in the Binational Californian Mediterranean Region. Land 2015, 4, 1138–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Censo de Población y Vivienda (CPV). 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/default.html#Microdatos (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.A.; Morales-Santos, A.E. Vulnerability Assessment to Climate Variability and Climate Change in Tijuana, Mexico. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria-Olazabal, T.; Ordoñez-Barba, G.M. Legalizando La Ciudad. Asentamientos Informales y Procesos de Regulación En Tijuan; El Colegio de la Frontera Norte: Tijuana, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bringas-Rabago, N.L.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.A. Social Vulnerability and Disaster Risk in Tijuana: Preliminary Findings. In Equity and Sustainable Development. Reflection from the U.S.-Mexico Border; Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies; UCSD: La Joya, TX, USA, 2006; pp. 150–172. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda-Revah, L.; Ochoa-Gonzalez, Y. Infraestructura Verde Para Tijuana, México. In Desarrollo Sostenible en la Frontera Norte de México: Reflexiones Para una Agenda de Acción; El Colegio de la Frontera Norte: Tijuana, Mexico, 2018; pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Comision Estatal del Agua. Sabes Cómo Llevamos el Agua Desde el Río Colorado Hasta las Ciudades de Tecate, Tijuana y Playas de Rosarito? Gobierno del Estado de Baja California: Playas de Rosarito, BC, Mexico, 2025. Available online: http://www.cea.gob.mx/documents/arct/perfil.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Operadores Sistemas de Agua Potable y Alcantarillado. Indicadores de Gestión. Organismos Operadores de Sistemas de Agua Potable y Alcantarillado; Gobierno del Estado de Baja California: Mexicali, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Melendez, G. La habitabilidad en una región de emergencia ambiental: El caso de la cuenca del río Tijuana. In Visiones Sobre La Habitabilidad Terrestre Y Humana Frente Al Cambio Climático. Una Primera Aproximación Epistemológica; Cervates-Nuñez, S., Ed.; UNAM: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2021; pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Minute 320 Binational Technical Team. Report of Transboundary Bypass Flows into the Tijuana River; International Boundary and Water Commission United States Mexico: San Diego, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Melendez, G. Capítulo 6. El vínculo agua-energía-desarrollo urbano en ciudades de la frontera norte. In Gestion del Agua en Mexico: Sustentabilidad y Gobernanza; Aguilar-Benitez, I., Ed.; El Colegio de la Frontera Norte: Tijuana, Mexico, 2020; pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaria de Proteccion al Ambiente. Programa Estatal de Accion ante el Cambio Climatico de Baja California; Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT), Gobierno del Estado de Baja California (GobBC) & Instituto Nacional de Ecologia (INE): Mexicali, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rebman, J.P.; Roberts, N.C. Baja California Plant Field Guide; San Diego Natural History Museum: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NOM-001-ECOL-1996; Que Establece los Límites Máximos Permisibles de Contaminantes en las Descargas de Aguas Residuales en Aguas y Bienes Nacionales. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 1997; p. 35.

- NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021; Que Establece los Límites Permisibles de Contaminantes en las Descargas de Aguas Residuales en Cuerpos Receptores Propiedad de la Nación. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2021; p. 18.

- NADF-020-AMBT-2011; QUE ESTABLECE LOS REQUERIMIENTOS MÍNIMOS PARA LA PRODUCCIÓN DE COMPOSTA A PARTIR DE LA FRACCIÓN ORGÁNICA DE LOS RESIDUOS SÓLIDOS URBANOS, AGRÍCOLAS, PECUARIOS Y FORESTALES, ASÍ COMO LAS ESPECIFICACIONES MÍNIMAS DE CALIDAD DE LA COMPOSTA PRODUCIDA Y/O DISTRIBUIDA EN EL DISTRITO FEDERAL. Gaceta Oficial del Distrito Federal: Ciudad de Mexico, 2012; p. 14.

- NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010; Protección Ambiental-Especies Nativas de México de Flora y Fauna Silvestres-Categorías de Riesgo y Especificaciones Para su Inclusión, Exclusión o Cambio-Lista de Especies en Riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2010.

- Zuniga-Teran, A.A.; Staddon, C.; de Vito, L.; Gerlak, A.K.; Ward, S.; Schoeman, Y.; Hart, A.; Booth, G. Challenges of Mainstreaming Green Infrastructure in Built Environment Professions. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 710–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado-López, J.A.; Galván-Benítez, R. Infraestructura verde. Conceptualización y análisis normativo de México Green Infrastructure. Conceptualization and legal analysis of Mexico. Quivera Rev. Estud. Territ. 2022, 24, 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Mesta, M.E. Servicios ambientales: Elementos para el desarrollo de un marco jurídico. Terra Latinoam. 2016, 34, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Balderas Torres, A.; Angón Rodríguez, S.; Sudmant, A.; Gouldson, A. Adapting to Climate Change in Mountain Cities: Lessons from Xalapa, Mexico; Coalition for Urban Transitions: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://urbantransitions.global/publications (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Secretaria de Medio Ambiente, de la Ciudad de México. Infraestructura Verde, Programa Especial de la Red de Infraestructu-ra Verde (PERIVE); Secretaria de Medio Ambiente, de la Ciudad de México, 2023. Available online: https://www.sedema.cdmx.gob.mx/programas/programa/infraestructura-verde (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- NOM-003-SEDATU-2023; Que Establece los Lineamientos Para el Fortalecimiento del Sistema Territorial Para Resistir, Adaptarse y Recuperarse Ante Amenazas de Origen Natural y del Cambio Climático a Través del Ordenamiento Territorial. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2024.

| NBS | Problems in Ecoparque | Solutions | Environmental Problems Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constructed wetland | “Siphon effect at wetland” (vacuum effect) | A TEE PVC piece venting to the atmosphere was installed. | Water scarcity by treating wastewater and reusing it in irrigation of greenspace |

| Substrate clogging with sediments | An ABR with plastic filers were installed before the inlet. Such filters are periodically cleaned. | ||

| Lack of wastewater inlets due to clogging | Contact the municipal provider of wastewater. The installation of a system of pipelines and pumps to recirculate water in the DEWAT system (biofilter, sedimentation tank, wetland, and maturation pond) | ||

| Reforestation with native plants | Introduction of exotic species | Long-term program to replace them with native plants | Biodiversity loss due to urbanization by conservation |

| Adaptation of native plants to the urban environment | Research on conditions needed by native plants to adapt to urban environments | Native plants propagation | |

| Steep slopes | Development of different slope retention techniques | Erosion and landslide risk | |

| Pest and disease control | Use of organic pesticides, pest control plant species and promoting plant biodiversity | ||

| Native species propagation | Research to develop plant propagation protocols, mainly by seed to ensure genetic variability | Lack of urban greenspace | |

| Social preference for lustrous vegetation of humid places | Promote awareness to appreciate native brown–green vegetation with attractive landscape designs | Social awareness of ecosystem conservation | |

| Compost producing | Quality of residues to be composted | Flyers informing on the “separation at source”, and acceptable residues were distributed to participating households. | Soil erosion and degradation by restoring moisture retention |

| Household enrolment | Incentives such as ornamental plants and 5 kg compost packages were given out. | Natural soil fertilization | |

| Rodents at the composting beds | Humidity and temperature control | ||

| Supersaturation of composting piles during the rainy season | Piles were covered with black sturdy plastic sheets. | ||

| Native ecosystems restoration | Lack of personnel for bird watching | Volunteerism of specialized personnel | Biodiversity loss by: |

| -Providing habitat for birds and other fauna | |||

| -Native vegetation conservation | |||

| Lack of personnel to monitor the natural vegetation patch | Research as master thesis topic | ||

| Edible forest | Thefts of tools and urban agricultural production | Sturdy lockers were bought to store tools | Biodiversity loss |

| Adaptation to local urban and site conditions | Seed selection of cultivars that thrive in urban conditions | Soil health improvement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ojeda-Revah, L.; Muñoz-Meléndez, G. Ecoparque: An Example of Nature-Based Solutions Implementation at Tijuana a Global South City. Land 2026, 15, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010089

Ojeda-Revah L, Muñoz-Meléndez G. Ecoparque: An Example of Nature-Based Solutions Implementation at Tijuana a Global South City. Land. 2026; 15(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleOjeda-Revah, Lina, and Gabriela Muñoz-Meléndez. 2026. "Ecoparque: An Example of Nature-Based Solutions Implementation at Tijuana a Global South City" Land 15, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010089

APA StyleOjeda-Revah, L., & Muñoz-Meléndez, G. (2026). Ecoparque: An Example of Nature-Based Solutions Implementation at Tijuana a Global South City. Land, 15(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010089