Policy Mix, Property Rights, and Market Incentives: Enhancing Farmers’ Bamboo Forest Management Efficiency and Productivity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. The Impact of Institutional Arrangements on Forestry Management Performance: An Integrated Perspective

2.2. Methods for Measuring Forestry Management Efficiency

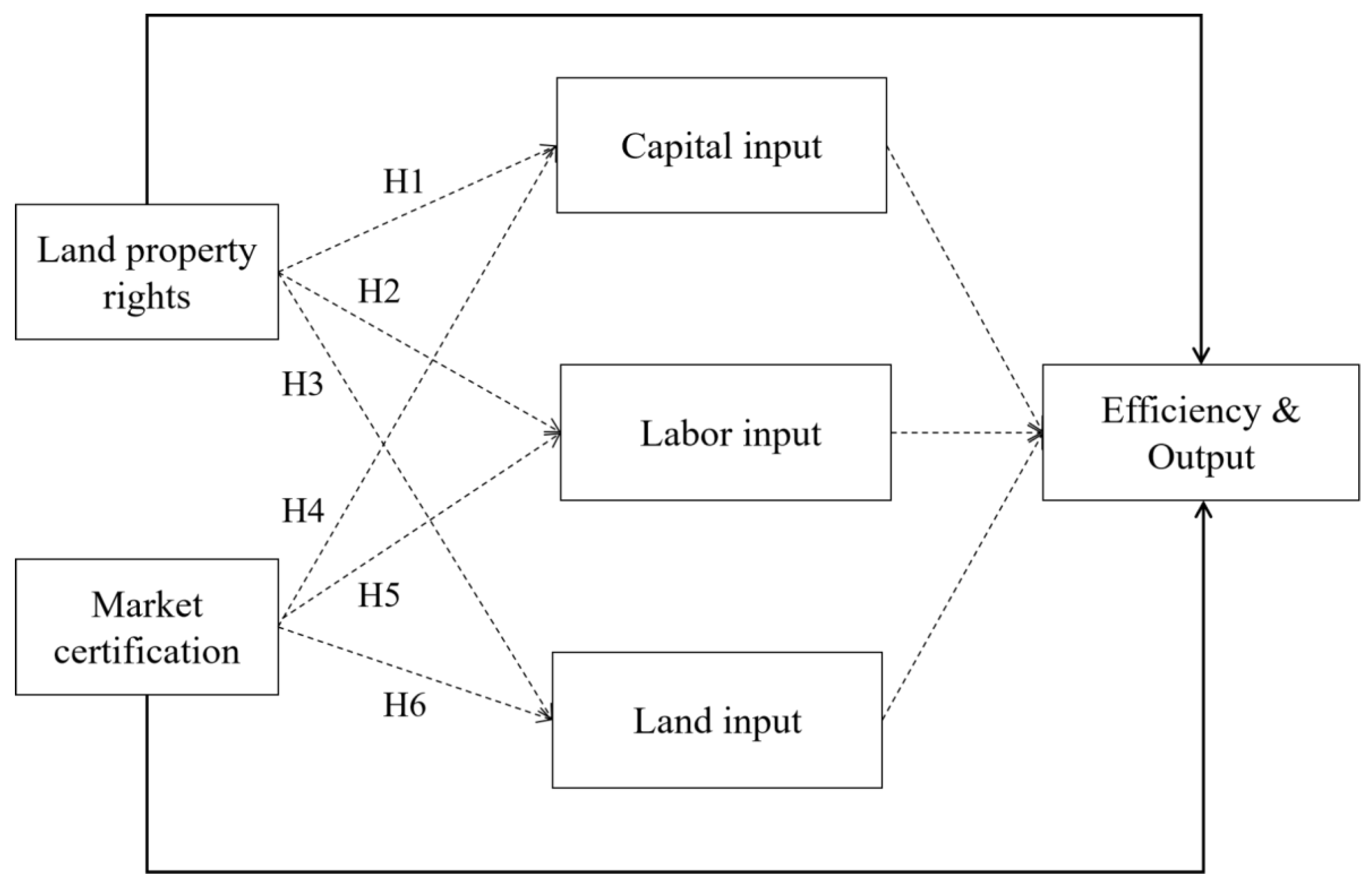

2.3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

3. Methods and Data

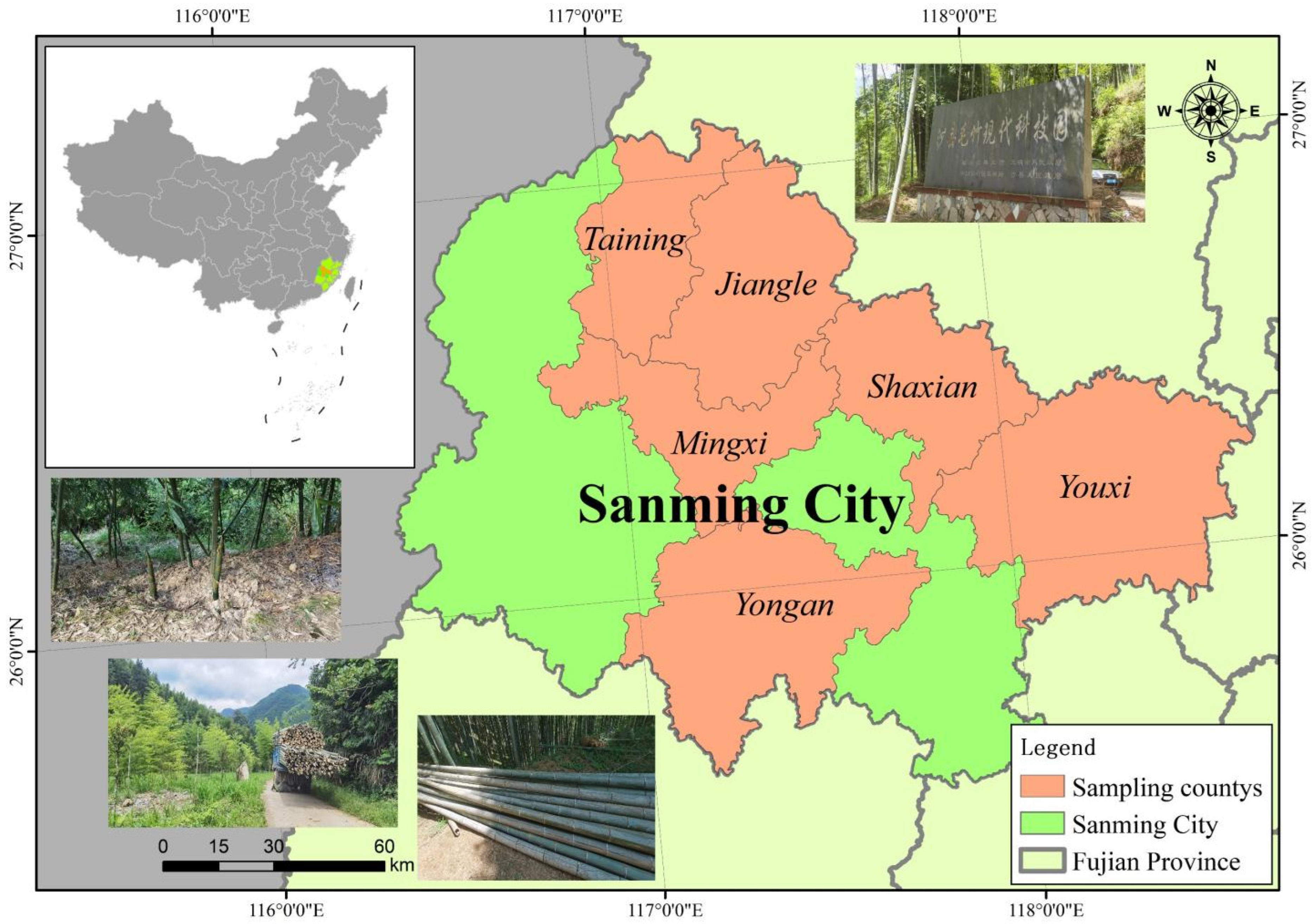

3.1. Study Area and Survey Design

3.2. Variable Selection and Descriptive Statistics

- (1)

- Management Performance: Bamboo output (aggregated peak/off-peak cycle yields, standardized to tonnes/mu) and technical efficiency (estimated via translog SFA).

- (2)

- Policy & Market Indicators: Binary variables for tenure certificate ownership and certification participation. Crucially, to satisfy the assumption of temporal precedence for causal inference, these variables define the household’s status held prior to or throughout the entire observed production cycle, ensuring that the institutional arrangements influenced the subsequent input and output decisions.

- (3)

- Mediators: Initially labor/capital/land inputs; subsequently refined to capital input (100 CNY/mu) and land input (mu) based on decision equation estimates.

- (4)

- Household Traits: Head’s gender/age/education; cadre/cooperative status; labor size; per capita income; monoculture management intensity.

- (5)

- Land Characteristics: Total area (mu), average slope (°), distance to residence (km), distance to nearest road (km).

- (6)

- Social Capital: Government connections (dummy), forestry enterprise ties (dummy).

- (7)

- Regional Controls: County-level certification availability (dummy), reflecting implementation scope.

3.3. Estimation of Management Efficiency and Input-Output Elasticities

3.4. Counterfactual Inference Model Specification

3.5. Mediating Effect Test of Factor Inputs

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Bamboo Forest Management Efficiency and Input-Output Elasticities

4.2.1. Impact of Factor Inputs on Management Efficiency

4.2.2. Output Elasticities of Factor Inputs

4.3. Policy Impact Assessment on Bamboo Management Performance

4.3.1. Propensity Score Estimation Results

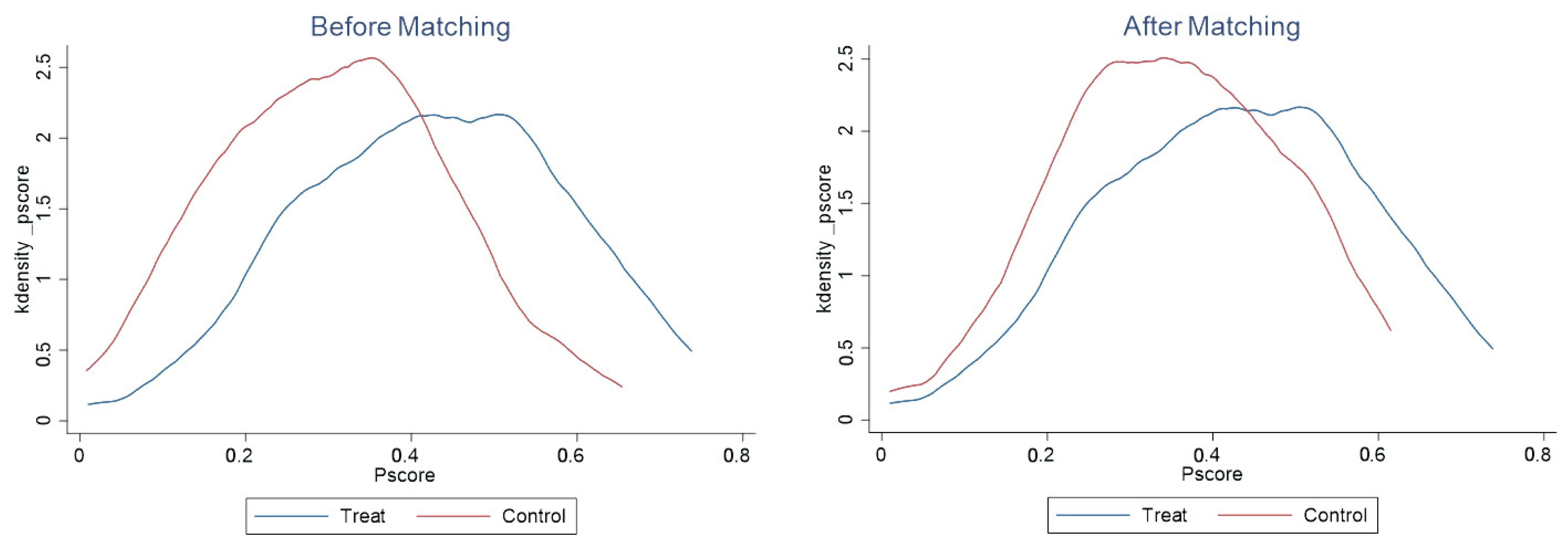

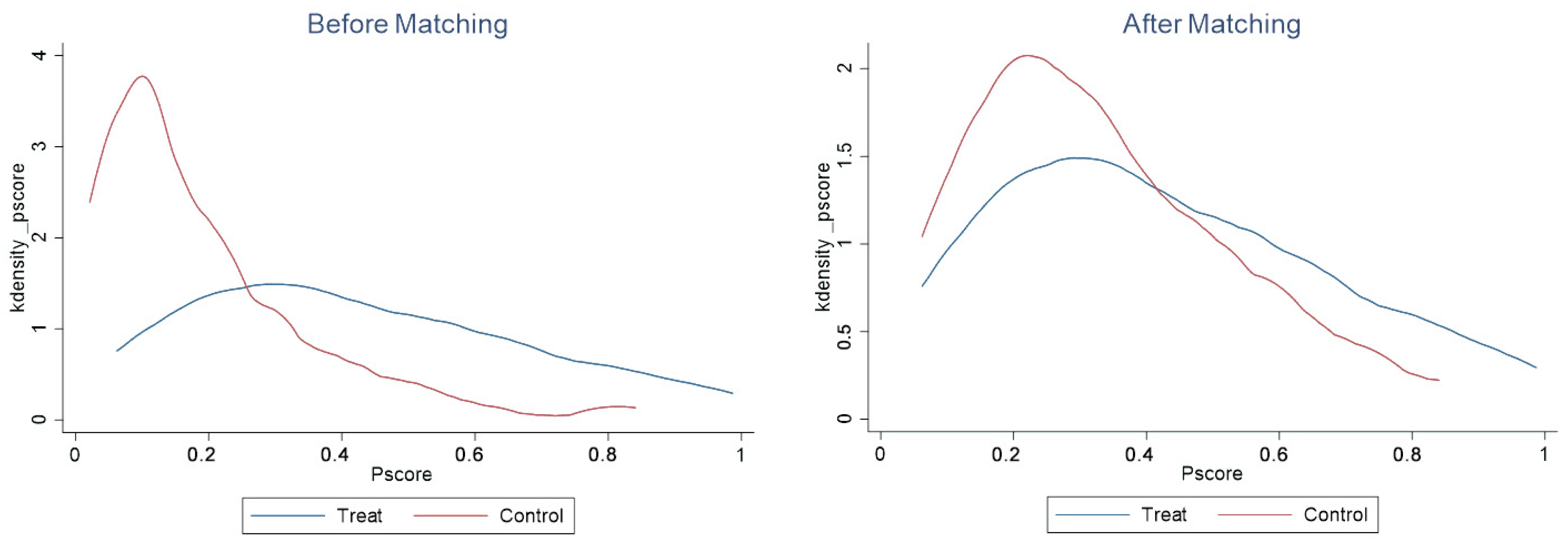

4.3.2. Common Support Domain Validation

4.3.3. Balance Test

4.3.4. PSM Treatment Effects

4.3.5. Robustness Check

4.4. Regression of Demographic Sociological Characteristics

5. Discussion

5.1. The “Output Growth Without Efficiency Gains” Dilemma of Property Rights

5.2. The Dual Advantage of Certification: Quality and Efficiency

5.3. Re-Evaluating the Roles of Factor Inputs

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Variable Description | Proportion (%) | Variable | Variable Description | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 93.35 | Education level | Illiterate | 10.33 |

| Female | 6.65 | Primary school | 49.08 | ||

| Age | Under 30 | 0.28 | Junior high school | 27.30 | |

| 30–40 | 3.25 | Senior high school | 10.18 | ||

| 41–50 | 14.29 | Bachelor’s degree or above | 3.11 | ||

| 51–60 | 37.63 | Health status | Major illness | 2.49 | |

| Over 60 | 44.55 | Minor illness | 3.39 | ||

| Party membership | Yes | 17.54 | Average | 5.86 | |

| No | 82.46 | Good | 88.26 | ||

| Whether a village cadre | Yes | 19.24 | Marital status | Married | 93.21 |

| No | 80.76 | Unmarried | 6.79 | ||

| Employment type | Farming only | 53.75 | Employment location | This village | 85.71 |

| Primarily farming | 23.46 | This town | 5.86 | ||

| Primarily non-farming | 8.49 | This county | 5.46 | ||

| Completely non-farming | 9.62 | This city | 1.13 | ||

| Unemployed | 4.68 | Other cities | 1.84 |

| Variable | Variable Description | Proportion (%) | Variable | Variable Description | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual per capita disposable income of the household (10,000 CNY) | Under 1 | 39.35 | Household population size | Under 3 | 7.38 |

| 1–2 | 26.17 | 3–5 | 46.58 | ||

| 2–3 | 16.23 | 6–8 | 39.87 | ||

| 3–4 | 6.69 | Over 8 | 6.17 | ||

| Over 4 | 11.56 | Number of household laborers | Under 3 | 40.65 | |

| Proportion of forestry income to household income | Under 10% | 70.42 | 3–5 | 54.64 | |

| 10–50% | 17.32 | Over 5 | 4.71 | ||

| 51–90% | 7.52 | Number of household members working away from home | 1 | 64.74 | |

| Over 90% | 4.74 | 2–3 | 30.69 | ||

| Household savings (10,000 CNY) | Under 1 | 20.34 | 4 or more | 4.58 | |

| 1–5 | 39.31 | Remaining household labor force (excluding migrant workers) | 1 | 42.10 | |

| 5–10 | 22.07 | 2 | 31.20 | ||

| Over 10 | 18.28 | 3 | 12.80 | ||

| 4 or more | 13.90 |

| Variable | Variable Description | Proportion (%) | Variable | Variable Description | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forestland area (mu) | Under 10 | 54.82 | Average slope of forestland | Good | 22.84 |

| 10–20 | 16.96 | Gentle | 36.26 | ||

| 21–30 | 7.16 | Relatively Steep | 36.58 | ||

| 31–50 | 8.77 | Very Steep | 27.16 | ||

| Over 50 | 12.28 | Average soil quality of forestland | Poor | 30.35 | |

| Number of forest plots | 1 | 67.74 | Average | 46.81 | |

| 2–3 | 29.17 | Good | 22.84 | ||

| 4 or more | 3.09 | Average distance of forestland from the main road | Within 1000 m | 61.66 | |

| Average distance of forestland from home | Within 1 km | 20.13 | 1000–3000 m | 31.79 | |

| 1–3 km | 53.99 | Over 3000 m | 6.55 | ||

| Over 3 km | 25.88 |

References

- FAO; UNEP. The State of the World’s Forests 2020: Forests, Biodiversity and People; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Ren, J.; Yang, J.; Wen, Y. How to Promote Sustainable Bamboo Forest Management: An Empirical Study from Small-Scale Farmers in China. Forests 2024, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ge, X.; Gao, G.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, B. Microbial pathways driving stable soil organic carbon change in abandoned Moso bamboo forests in southeast China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Ge, X.; Gao, G.; Cao, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, B. Trade-offs between ligninase and cellulase and their effects on soil organic carbon in abandoned Moso bamboo forests in southeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y. Devolution of tenure rights in forestland in China: Impact on investment and forest growth. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 154, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, P.; Sills, E.O. Inviting oversight: Effects of forest certification on deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. World Dev. 2024, 173, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeta, D.; Ayana, A.N. The contribution of forest coffee certification program to household income and resource conservation: Empirical evidences from Southwest Ethiopia. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 25, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The Problem of Social Cost. In Classic Papers in Natural Resource Economics; Gopalakrishnan, C., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1960; pp. 87–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadera, A.; Tadesse, T.; Zeweld, W.; Tesfay, G.; Gebremedhin, B. Trust, tenure security and investment in high-value forests. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 166, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolde, A.A. Assessing the dynamic impact of formal and perceived land rights on fruit tree cultivation: Exploring the moderating role of forest ecology, gender, and land acquisition method. Trees For. People 2025, 20, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sun, H. The Impact of Collective Forestland Tenure Reform on the Forest Economic Efficiency of Farmers in Zhejiang Province. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wen, C.; Li, Y. The heterogeneous effect of forest tenure security on forestry management efficiency of farmers for different forest management types. For. Econ. Rev. 2022, 4, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnet, M.B.; van der Werf, E.; Ingram, V.; Wesseler, J. Community perceptions: A comparative analysis of community participation in forest management: FSC-certified and non-certified plantations in Mozambique. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 143, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, F.X.; Vlosky, R.P. Consumer willingness to pay price premiums for environmentally certified wood products in the U.S. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollert, W.; Lagan, P. Do certified tropical logs fetch a market premium?: A comparative price analysis from Sabah, Malaysia. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, A.; Rivera, J. Producer-Level Benefits of Sustainability Certification: Benefits of Sustainability Certification. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.T.; Otsuka, K.; Deininger, K. (Eds.) Land Tenure Reform in Asia and Africa: Assessing Impacts on Poverty and Natural Resource Management; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some Models for Estimating Technical and Scale Inefficiencies in Data Envelopment Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.; Petersen, N.C. A Procedure for Ranking Efficient Units in Data Envelopment Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1993, 39, 1261–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossin, M.A.; Alemzero, D.; Wang, R.; Kamruzzaman, M.M.; Mhlanga, M.N. Examining artificial intelligence and energy efficiency in the MENA region: The dual approach of DEA and SFA. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 4984–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W. A stochastic frontier model with correction for sample selection. J. Prod. Anal. 2010, 34, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhakar, S.C.; Wang, H.J.; Horncastle, A.P. A Practitioner’s Guide to Stochastic Frontier Analysis Using Stata; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karner, K.; Schmid, E.; Schneider, U.A.; Mitter, H. Computing stochastic Pareto frontiers between economic and environmental goals for a semi-arid agricultural production region in Austria. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 185, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Chen, N.; Wang, S.; Cao, F. Does forestry industry integration promote total factor productivity of forestry industry? Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitole, F.A.; Tibamanya, F.Y.; Sesabo, J.K. Exploring the nexus between health status, technical efficiency, and welfare of small-scale cereal farmers in Tanzania: A stochastic frontier analysis. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourjade, S.; Muller-Vibes, C. Optimal leasing and airlines’ cost efficiency: A stochastic frontier analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 176, 103804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso de Mendonça, M.J.; Pereira, A.O.; Medrano, L.A.; Pessanha, J.F.M. Analysis of electric distribution utilities efficiency levels by stochastic frontier in Brazilian power sector. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 76, 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-García, J.S.; Pérez-Rodríguez, J.V. Heterogeneity and time-varying efficiency in the Ecuadorian banking sector. An output distance stochastic frontier approach. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 93, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, H.G.; Li, G.; Rozelle, S. Hazards of Expropriation: Tenure Insecurity and Investment in Rural China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1420–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Martin, F.; Cook, S.; He, X.; Halberg, N.; Scott, S.; Pan, X. Certified Organic Agriculture as an Alternative Livelihood Strategy for Small-scale Farmers in China: A Case Study in Wanzai County, Jiangxi Province. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathi, P.; Waibel, H. Organic Agriculture and Fair Trade: A Happy Marriage? A Case Study of Certified Smallholder Black Pepper Farmers in India. World Dev. 2016, 77, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-F.; Cheng, C.-Y. Exploring the distribution of organic farming: Findings from certified rice in Taiwan. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 212, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ho, B.; Nanseki, T.; Chomei, Y. Profit efficiency of tea farmers: Case study of safe and conventional farms in Northern Vietnam. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1695–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Song, M.; Zhu, Z. Stochastic frontier analysis of productive efficiency in China’s Forestry Industry. J. For. Econ. 2017, 28, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddu, M.; Senyonga, L.; Sseruyange, J.; Watundu, S.; Ngoma, M.; Turyareeba, D. Fuelwood collection and technical efficiency among rural households in Uganda: An instrumental variable-stochastic frontier analysis approach. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 5968–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Wang, F.; Cheng, B.; Yu, C. Identifying factors influencing the forestry production efficiency in Northwest China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 130, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battese, G.E.; Coelli, T.J. A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic frontier production function for panel data. Empir. Econ. 1995, 20, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Liao, L.; Fu, T.; Lan, S. Do establishment of protected areas and implementation of regional policies both promote the forest NPP? Evidence from Wuyi Mountain in China based on PSM-DID. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 55, e03210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Bi, Y.; Yu, L. Understanding the impacts of ecological compensation policy on rural livelihoods: Insights from forest communities of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 123921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, W.; Yu, W.; Wu, T. Combined effects of urban forests on land surface temperature and PM2.5 pollution in the winter and summer. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 104, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. Constructing a Control Group Using Multivariate Matched Sampling Methods That Incorporate the Propensity Score. Am. Stat. 1985, 39, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemes, P.G.; Zanuncio, J.C.; Jacovine, L.A.G.; Wilcken, C.F.; Lawson, S.A. Forest Stewardship Council and Responsible Wood certification in the integrated pest management in Australian forest plantations. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’ Doua, B.D. The impact of forest management certification on exports in the wood sector: Evidence from French firm-level data. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Description | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Bamboo forest output | tons/mu | 2.254 | 0.898 |

| Technical efficiency | 0–1 | 0.557 | 0.165 | |

| Treatment Variables | Participation in bamboo forest certification | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.129 | 0.336 |

| Holding a forest tenure certificate | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.606 | 0.489 | |

| Mediating Variables | Capital input | 100 CNY/mu | 4.690 | 2.872 |

| Land input | mu | 39.83 | 20.271 | |

| Household Characteristics | Gender of household head | 1 = Male; 0 = Female | 0.931 | 0.259 |

| Age of household head | Years old | 60.049 | 10.982 | |

| Education level of household head | Years | 6.495 | 3.668 | |

| Whether the household head is a village cadre | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.085 | 0.279 | |

| Membership in a forestry cooperative | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.172 | 0.377 | |

| Number of household laborers | People | 3.406 | 1.339 | |

| Annual per capita income of the household | 10,000 CNY | 2.909 | 4.766 | |

| Proportion of forestry income to total household income | % | 15.141 | 27.414 | |

| Forestland Attributes | Forestland area | mu | 35.682 | 146.962 |

| Average slope of forestland | 1 = Gentle slope; 2 = Relatively steep; 3 = Very steep | 1.819 | 0.804 | |

| Average distance of forestland from home | km | 5.040 | 21.100 | |

| Average distance of forestland from the main road | km | 1.395 | 4.653 | |

| Social Network Features | Whether relatives or friends are government employees | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.186 | 0.384 |

| Whether relatives or friends manage a forestry enterprise | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.102 | 0.302 | |

| Regional Characteristics | Whether bamboo forest certification is available/conducted in the county | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.333 | 0.475 |

| Variable | Parameter Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.299 ** | 1.908 | 2.254 |

| Labor input | 0.089 | 0.385 | 0.231 |

| Capital input | 1.026 *** | 0.389 | 2.637 |

| Land input | 1.031 ** | 0.437 | 2.362 |

| Labor input squared | 0.096 | 0.042 | 2.286 |

| Capital input squared | 0.077 *** | 0.033 | 2.333 |

| Land input squared | −0.075 * | 0.064 | −1.168 |

| Labor input × Capital input | −0.065 | 0.048 | −1.354 |

| Labor input × Land input | 0.036 | 0.088 | 0.417 |

| Land input × Capital input | −0.042 | 0.070 | −0.604 |

| 1.438 *** | 0.444 | 3.238 | |

| 0.665 ** | 0.283 | 1.995 | |

| Log likelihood | −239.816 | ||

| LR one-sided test | 2.328 * > Critical value: 1.642 (10% significance level) | ||

| Mean technical efficiency | 0.557 | ||

| Technical Efficiency | Sample Proportion | Labor Elasticity | Capital Elasticity | Land Elasticity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0–0.25) | 6.90% | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.82 |

| [0.25–0.50) | 28.74% | 0.14 | 0.69 | 0.81 |

| [0.50–0.75) | 56.32% | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.81 |

| [0.75–1] | 8.05% | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.86 |

| Mean | 100.00% | 0.13 | 0.68 | 0.81 |

| Variable | Holding a Forest Tenure Certificate | Participation in Bamboo Forest Certification |

|---|---|---|

| Gender of household head | 0.008 (0.772) | −2.163 *** (0.726) |

| Age of household head | 0.023 (0.019) | −0.001 (0.019) |

| Education level of household head | 0.030 (0.068) | 0.047 (0.071) |

| Whether the household head is a village cadre | 0.633 * (0.855) | 1.228 * (0.732) |

| Membership in a forestry cooperative | 0.772 (0.503) | 0.205 (0.505) |

| Number of household laborers | 0.164 (0.151) | 0.264 (0.166) |

| Annual per capita income of the household | 0.075 (0.721) | 0.097 (0.074) |

| Proportion of forestry income to total household income | 0.021 *** (0.007) | 0.014 ** (0.007) |

| Forestland area | 0.109 * (0.007) | 0.014 ** (0.005) |

| Average slope of forestland | 0.193 (0.271) | −0.107 (0.268) |

| Average distance of forestland from home | 0.026 (0.018) | −0.002 (0.007) |

| Average distance of forestland from the main road | 0.109 * (0.169) | −0.044 (0.131) |

| Whether relatives or friends are government employees | 0.451 * (0.567) | 0.535 (0.550) |

| Whether relatives or friends manage a forestry enterprise | 0.678 (0.715) | 1.491 * (0.848) |

| Whether bamboo forest certification is available in the county | — | 0.602 (0.550) |

| LR statistic | 39.900 *** | 43.970 *** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.193 | 0.214 |

| Matching Method | Holding a Forest Tenure Certificate | Participation in Bamboo Forest Certification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo R2 | LR Statistic | MeanBias | Pseudo R2 | LR Statistic | MeanBias | |

| Unmatched | 0.195 | 40.28 *** | 20.50 | 0.218 | 44.63 *** | 22.70 |

| K-Nearest Neighbor Matching | 0.093 | 6.12 | 8.20 | 0.084 | 6.44 | 7.20 |

| K-Nearest Neighbor Matching within Caliper | 0.058 | 3.53 | 4.80 | 0.053 | 6.74 | 9.30 |

| Radius Matching | 0.087 | 4.13 | 5.32 | 0.076 | 5.53 | 6.10 |

| Kernel Matching | 0.027 | 1.52 | 7.87 | 0.019 | 2.22 | 7.60 |

| Management Performance Indicator | Matching Method | Forest Tenure Certificate (ATT) | Bamboo Forest Certification (ATT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bamboo forest output | K-Nearest Neighbor Matching | 1.666 *** (0.353) | 1.642 *** (0.507) |

| K-Nearest Neighbor Matching within Caliper | 1.650 *** (0.356) | 1.513 *** (0.495) | |

| Radius Matching | 1.800 *** (0.131) | 1.873 *** (0.515) | |

| Kernel Matching | 1.666 *** (0.343) | 1.221 *** (0.470) | |

| Mean (significant only) | 1.696 | 1.562 | |

| Technical efficiency | K-Nearest Neighbor Matching | 0.063 (0.057) | 0.715 (0.045) |

| K-Nearest Neighbor Matching within Caliper | 0.050 (0.054) | 0.069 *** (0.037) | |

| Radius Matching | 0.025 (0.015) | 0.044 *** (0.021) | |

| Kernel Matching | 0.052 (0.055) | 0.032 *** (0.033) | |

| Mean (significant only) | - | 0.048 |

| Sample Group | Bamboo Forest Output | Technical Efficiency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | |

| Has tenure certificate and participates in bamboo certification | 3.54 | 3.40 | 1.58 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.12 |

| No tenure certificate and does not participate in bamboo certification | 1.46 | 1.30 | 1.09 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.18 |

| Absolute difference | 2.08 | 2.10 | - | 0.08 | 0.04 | - |

| Has tenure certificate | 3.30 | 3.00 | 1.43 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.16 |

| No tenure certificate | 1.50 | 1.30 | 1.07 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.18 |

| Absolute difference | 1.80 | 1.70 | - | 0.03 | 0.20 | - |

| ATT | 1.70 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Participates in bamboo certification | 3.54 | 3.40 | 1.58 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.12 |

| Does not participate in bamboo certification | 1.76 | 1.88 | 1.55 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.17 |

| Absolute difference | 1.78 | 1.52 | - | 0.06 | 0.02 | - |

| ATT | 1.56 | - | - | 0.05 | - | - |

| Gamma (Γ) | Forest Tenure Certificate (Bamboo Forest Output) | Forest Tenure Certificate (Technical Efficiency) | Bamboo Certification (Bamboo Forest Output) | Bamboo Certification (Technical Efficiency) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p+ | p− | p+ | p− | p+ | p− | p+ | p− | |

| 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.014 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| X | Mediator | Y | Direct Effect | 90% CI | Indirect Effect | 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has tenure certificate | Capital input | Technical efficiency | 0.020 | −0.027, 0.068 | 0.005 | −0.005, 0.020 |

| Land input | 0.025 | −0.023, 0.072 | 0.001 | −0.008, 0.011 | ||

| Capital input | Bamboo output | 0. 127 | −0.182, 0.437 | 0.463 | 0.244, 0.708 | |

| Land input | 0.181 | −0.117, 0.478 | 0.409 | 0.177, 0.668 | ||

| Participates in bamboo certification | Capital input | Technical efficiency | 0.048 | −0.001, 0.097 | 0.004 | −0.013, 0.020 |

| Land input | 0.056 | 0.006, 0.106 | 0.004 | −0.025, 0.012 | ||

| Capital input | Bamboo output | 0.619 | 0.309, 0.928 | 0.559 | 0.355, 0.785 | |

| Land input | 0.493 | 0.183, 0.803 | 0.684 | 0.487, 0.901 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Feng, J.; Wen, Y. Policy Mix, Property Rights, and Market Incentives: Enhancing Farmers’ Bamboo Forest Management Efficiency and Productivity. Land 2026, 15, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010088

Huang Y, Feng J, Wen Y. Policy Mix, Property Rights, and Market Incentives: Enhancing Farmers’ Bamboo Forest Management Efficiency and Productivity. Land. 2026; 15(1):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010088

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yuan, Ji Feng, and Yali Wen. 2026. "Policy Mix, Property Rights, and Market Incentives: Enhancing Farmers’ Bamboo Forest Management Efficiency and Productivity" Land 15, no. 1: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010088

APA StyleHuang, Y., Feng, J., & Wen, Y. (2026). Policy Mix, Property Rights, and Market Incentives: Enhancing Farmers’ Bamboo Forest Management Efficiency and Productivity. Land, 15(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010088