Ecological Assessment Based on the InVEST Model and Ecological Sensitivity Analysis: A Case Study of Huinan County, Tonghua City, Jilin Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material

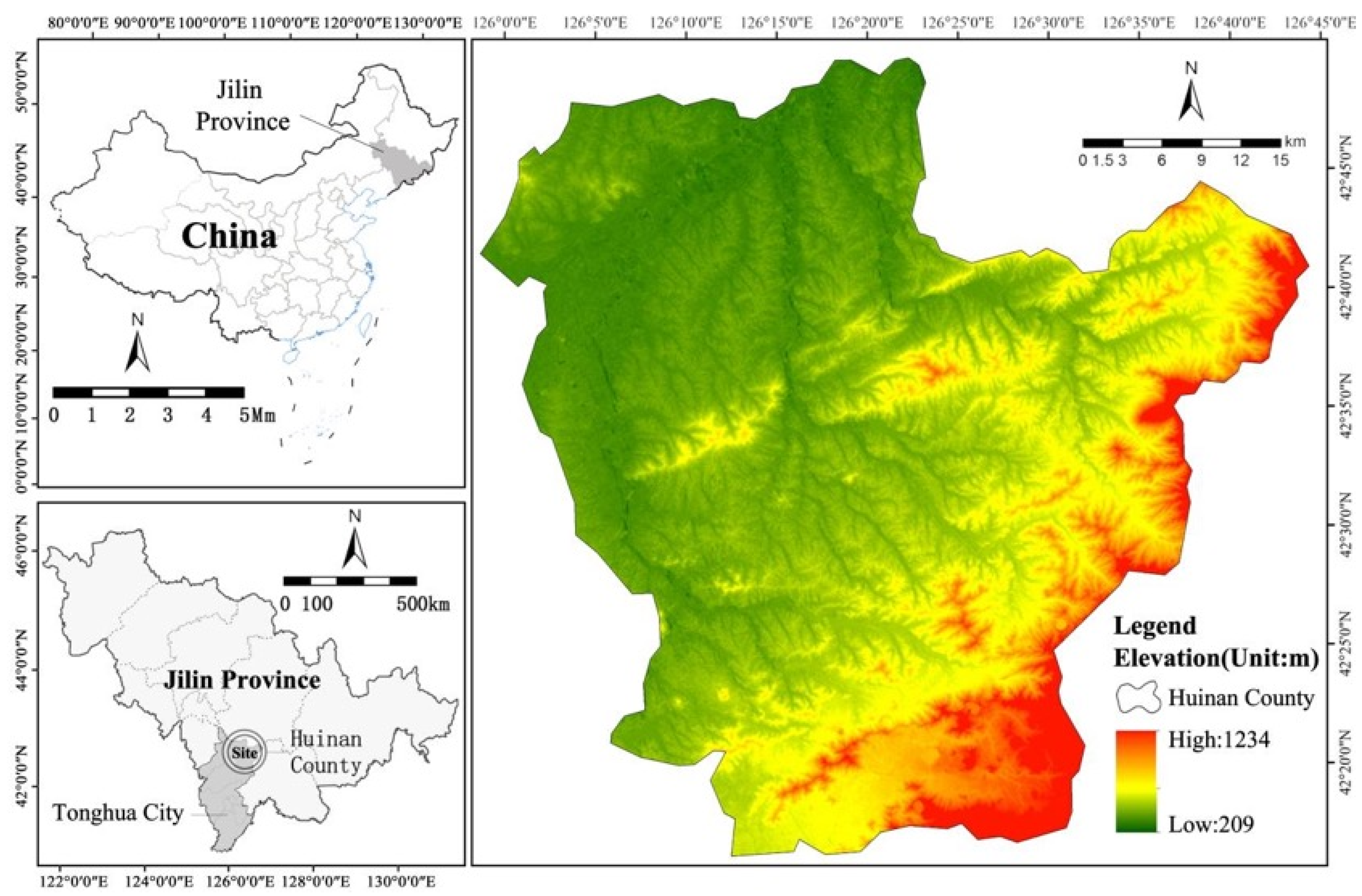

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

3. Method

3.1. DPSIRM Framework Model

3.1.1. Constructing an Evaluation Indicator System

3.1.2. Determination of Grading Criteria and Evaluation Methods

3.2. InVEST Model

3.3. Coupling Analysis of Ecological Sensitivity and the InVEST Model

4. Result

4.1. Ecological Sensitivity Classification

4.2. Carbon Stock Content Distribution

4.3. Ecological Protection Zone Delineation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harris, J.A.; Hobbs, R.J.; Higgs, E.; Aronson, J. Ecological restoration and global climate change. Restor. Ecol. 2006, 14, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabrook, L.; McAlpine, C.A.; Bowen, M.E. Restore, repair or reinvent: Options for sustainable landscapes in a changing climate. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Hu, H.F.; Sun, W.J.; Zhu, J.J.; Liu, G.B.; Zhou, W.M.; Zhang, Q.F.; Shi, P.L.; Liu, X.P.; Wu, X.; et al. Effects of national ecological restoration projects on carbon sequestration in China from 2001 to 2010. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4039–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.Q.; Du, C.; Wang, X.G. Analysis and Forecast of Land Use and Carbon Sink Changes in Jilin Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Dupre, K.; Wang, Y. Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.J.; Shi, X.Y.; He, J.; Yuan, Y.; Qu, L.L. Identification and optimization strategy of county ecological security pattern: A case study in the Loess Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Li, Z.; Lin, S.; Xu, W. Assessment and zoning of eco-environmental sensitivity for a typical developing province in China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2012, 26, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kap Yücel, S.D. Multifactor sensitivity assessment for spatial planning in Izmir, Turkey. Urbani. Izziv. 2023, 34, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, L.; Boeni, A.F.; Prohászka, V.J.; Szilágyi, A.; Kovács, E.T.; Pásztor, L.; Centeri, C. InVEST Soil Carbon Stock Modelling of Agricultural Landscapes as an Ecosystem Service Indicator. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Li, R.; Liu, M.; Cao, Y.; Yang, J.; Wei, Y. Analysis of Carbon Storage Changes in the Chengdu–Chongqing Region Based on the PLUS-InVEST-MGWR Model. Land 2025, 14, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, S.S.; Zou, Y.T. Construction of an ecological security pattern based on ecosystem sensitivity and the importance of ecological services: A case study of the Guanzhong Plain urban agglomeration, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.J.; Ma, C.M.; Huang, P.; Guo, X. Ecological vulnerability assessment based on AHP-PSR method and analysis of its single parameter sensitivity and spatial autocorrelation for ecological protection? A case of Weifang City, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.Q.; Jiao, L.M.; Lian, X.H.; Wang, W.L. Linking supply-demand balance of ecosystem services to identify ecological security patterns in urban agglomerations. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 92, 104497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.Y.; Fu, B.J.; Ma, R.M.; Lü, Y.H.; Wu, X. Identifying ecological security patterns based on the supply, demand and sensitivity of ecosystem service: A case study in the Yellow River Basin, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, S.D.; Wu, T.X.; Li, X.K.; Wang, J.N.; Wang, D.C.; Zhu, H.T.; Tan, C.; Ji, Y.H. Spatiotemporal evolution of ecological vulnerability in the Yellow River Basin under ecological restoration initiatives. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 135, 108586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.Y.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Q.X.; Zhao, Y.Y. Assessing the potential impacts of urban expansion on regional carbon storage by linking the LUSD-urban and InVEST models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 75, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Mo, X.Y.; Ji, H.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.S.; Bao, Z.L.; Li, T.H. Comparison of the CASA and InVEST models’ effects for estimating spatiotemporal differences in carbon storage of green spaces in megacities. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.W.; Hu, Y.C.; Bai, Y.P. Construction of ecological security pattern in national land space from the perspective of the community of life in mountain, water, forest, field, lake and grass: A case study in Guangxi Hechi, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 139, 108867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.Q.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, S.N.; Liu, C.H. Evaluation and drive mechanism of tourism ecological security based on the DPSIR-DEA model. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricio, J.; Elliott, M.; Mazik, K.; Papadopoulou, K.N.; Smith, C.J. DPSIR-Two Decades of Trying to Develop a Unifying Framework for Marine Environmental Management? Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.; Li, W.L.; Xu, J.; Zhou, H.K.; Li, C.H.; Wang, W.Y. Global trends and characteristics of ecological security research in the early 21st century: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, X.Y.; Sun, D.Q. A Coupled InVEST-PLUS Model for the Spatiotemporal Evolution of Ecosystem Carbon Storage and Multi-Scenario Prediction Analysis. Land 2024, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, P.; van der Plas, F.; Soliveres, S.; Allan, E.; Maestre, F.T.; Mace, G.; Whittingham, M.J.; Fischer, M. Redefining ecosystem multifunctionality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.H. Research on the Sustainable Development in Forestry in Huinan Country, Jilin Province. 2000. Available online: https://www.doc88.com/p-7387013310987.html (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Guo, Y.H.; Tong, L.J.; Mei, L. Spatiotemporal characteristics and influencing factors of agricultural eco-efficiency in Jilin agricultural production zone from a low carbon perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 29854–29869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, S.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Ran, Q.; Gao, X.; Ding, X.; Ge, D. Spatial-Temporal Evolution and Prediction of Carbon Storage: An Integrated Framework Based on the MOP–PLUS–InVEST Model and an Applied Case Study in Hangzhou, East China. Land 2022, 11, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.L.; Wu, J.P.; Zhang, F.T.; Su, W.C.; Hui, H. Evaluating Water Resource Security in Karst Areas Using DPSIRM Modeling, Gray Correlation, and Matter-Element Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.M.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, X.C.; You, Y.; Li, X.T.; Wu, J. Water Resources Carrying Capacity Based on the DPSIRM Framework: Empirical Evidence from Shiyan City, China. Water 2023, 15, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hao, Y.R.; Wang, B.; Li, X.Y.; Gao, W.F. Evaluation of the water resources carrying capacity in Shaanxi Province based on DPSIRM-TOPSIS analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173, 113369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, X.P.; Zhang, Y.F. Ecological health assessment of an arid basin using the DPSIRM model and TOPSIS-A case study of the Shiyang River basin. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 111973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Environmental Protection Standard of the People’s Republic of China. HJ 589-2010 Technical Specifications for Emergency Monitoring of Sudden Environmental Incidents. Environ. Prot. Oil Gas Fields 2011, 21, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y. Research on Optimizing the Management of Ecological Protection Redlines in China’s New Era. Jilin University, 2024. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/D03507682 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Zheng, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Gou, H.; Wang, G. Ecological Sensitivity Assessment of the Northern Foothills of the Qinling Mountains Based on the DPSIRM and PLUS Models. J. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 244–252. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, B.T.; Bao, X.Y.; Zhao, J.C. Evaluation Method and Application of Ecological Sensitivity of Intercity Railway Network Planning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.F.; Dong, W.Q.; Liu, T.; Fang, L. Exploring ecosystem sensitivity patterns in China: A quantitative analysis using the Importance-Vulnerability-Sensitivity framework and neighborhood effects method. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, D.K.; Tang, L.N.; Shao, G.F. A comprehensive assessment of ecological sensitivity for a coal-fired power plant in Xilingol, Inner Mongolia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2017, 24, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.H. Research on estimation of slope stability based on improved grey correlation analysis and analytic hierarchy process. Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 3437–3441. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Qiu, W.; Zhao, Q.-L.; Liu, Z.-M. Applying analytical hierarchy process to assess eco-environment quality of Heilongjiang province. Huanjing Kexue 2006, 27, 1031–1034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wei, H.; Ni, X.-L.; Gu, Y.-W.; Li, C.-X. Evaluation of urban human settlement quality in Ningxia based on AHP and the entropy method. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 25, 2700–2708. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Hui, G.; Xin-Jie, W.; Yue-Xin, C.; Gui-Mei, Z.; Zi-Ye, Y.; Hui-Nan, W.; Pei-Hua, W.; Meng-Yu, C.; Ying-Zi, W. Application research of entropy weight-based grey systematic theory in quality evaluation of Angelicae Sinensis Radix slices. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2020, 45, 5200–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Min, D.; Yoo, G.; Park, Y.L.; Sung, K.; Kim, B.W. Evaluation of Grassland Carbon Storage in Gangwon Province Using the InVEST Model and Application of Land Cover Maps. J. Korean Soc. Grassl. Sci. 2024, 44, 301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Sharma, H.; Jadav, M.; Hettiarachchi, U.; Guha, C.; Zhang, W.; Priyadarshini, P.; Meinzen-Dick, R.S. Measuring above-ground carbon stock using spatial analysis and the InVEST model: Application in the Thoria Watershed, India. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 115036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D. Assessment of Carbon Storage under Different SSP-RCP Scenarios in Terrestrial Ecosystems of Jilin Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.F.; Li, M.Y.; Jin, G.Z. Exploring the optimization of spatial patterns for carbon sequestration services based on multi-scenario land use/cover changes in the changchun-Jilin-Tumen region, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 438, 140788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Liu, Z.S.; Li, S.J.; Li, X. Multi-Scenario Simulation Analysis of Land Use and Carbon Storage Changes in Changchun City Based on FLUS and InVEST Model. Land 2022, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, D.; Dan, S.F.; Kang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Weng, P.; Wei, Z. Ecological security assessment of Qinzhou coastal zone based on Driving forces-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) model. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1009897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Su, P. Evaluation of the vulnerability of Huanghe estuary coastal wetlands to marine oil spill stress. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1481868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiong, X.; Jiang, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Ji, G.; Qian, B. Integrating PLUS and InVEST model to project carbon dynamics in China’s yellow river basin under multi-scenarios (1980–2100). Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1684333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yeob, K.D. A Study on the Establishment of the Standard for Buffering Region in Railway Development Areas. Ecol. Resilient Infrastruct. 2018, 5, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.; Gochfeld, M.; Brown, K.G.; Ng, K.; Cortes, M.; Kosson, D. The importance of recognizing Buffer Zones to lands being developed, restored, or remediated: On planning for protection of ecological resources. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A Curr. Issues 2024, 87, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, Ü.; Kuusemets, V.; Hayakawa, Y. Purification processes, ecological functions, planning and design of riparian buffer zones in agricultural watersheds. Ecol. Eng. 2005, 24, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Categories | Data Name | Resolution | Data Usage | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Geography | Administrative boundary | Define the spatial scope of the study area as the basis for all data preprocessing. | http://www.resdc.cn/data (accessed on 2 April 2025) | |

| Land cover | Land Use Type | 30 m | Extract vegetation cover information and classify land use types. | https://www.gscloud.cn/ (accessed on 2 April 2025) |

| Socioeconomic factors | Population density | 1 km | Quantifying human activity intensity as an anthropogenic driver for ecological sensitivity assessment | http://gis5g.com/home (accessed on 4 April 2025) |

| GDP density | 1 km | http://gis5g.com/home (accessed on 4 April 2025) | ||

| Climate and environmental factors | NDVI | 30 m | Analyze vegetation coverage and growth conditions. | http://gis5g.com/home (accessed on 2 April 2025) |

| Roads data | Generate road buffer rasters to characterize the impact of traffic disturbance on ecological sensitivity. | https://www.webmap.cn (accessed on 8 April 2025) | ||

| Water data | Generate a water body buffer zone raster to quantify the impact of hydrological conditions on ecological sensitivity. | https://www.webmap.cn (accessed on 8 April 2025) | ||

| DEM | 30 m | Extract terrain factors such as slope gradient and aspect to support the quantification of terrain-related indicators. | https://www.gscloud.cn (accessed on 5 April 2025) | |

| Average temperatures | 1 km | Generate climate grid maps to support the analysis of climate factors in ecological sensitivity assessments. | http://gis5g.com/home (accessed on 10 April 2025) | |

| Relative humidity | 1 km | http://gis5g.com/home (accessed on 15 April 2025) | ||

| Average annual precipitation | 1 km | http://gis5g.com/home (accessed on 15 April 2025) | ||

| Grain production per unit area | 1 km | Reflect the intensity of agricultural production’s disturbance to soil carbon pools and vegetation cover. | https://www.nesdc.org.cn/ (accessed on 16 April 2025) |

| Normative Layer | Indicator Layer | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Driving Force | Population density | Number of people living per unit area of land |

| DEM | Topographic surface elevation information | |

| Slope | Degree of inclination of a region | |

| Slope direction | Slope orientation of topographic surfaces | |

| Pressure | Road buffer zone | Areas demarcated on both sides of the road |

| Water Buffer Zone | Areas delineated on both sides of the river | |

| State | Degree of topographic relief | Dramatic changes in terrain elevation |

| Surface cut | Fragmentation and complexity of the terrain | |

| Terrain roughness | Complexity of terrain elevation changes | |

| Vegetation cover | Degree of vegetation cover | |

| Land use type | Functions of land over time and space | |

| Impact | Average temperatures | General level of temperatures |

| Relative humidity | Atmospheric water vapor content | |

| Average annual precipitation | Status of water resources | |

| Response | GDP | Total economic activity |

| Grain production per unit area | Agricultural productivity and technology levels | |

| Management | Eco-environmental protection policy |

| LULC_Code | LULC_Name | C_Above | C_Below | C_Soil | C_Dead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cultivated Land | 0.8 | 0 | 41 | 0 |

| 2 | Forest | 52.5 | 16.8 | 72.1 | 2.25 |

| 3 | Grassland | 1.4 | 1.7 | 26.8 | 2.84 |

| 4 | Water Areas | 10.5 | 30.2 | 66.2 | 0 |

| 5 | Construction Land | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Unutilized Land | 0 | 0 | 21 | 0 |

| Normative Layer | Indicator Layer | AHP Weight | EWM Weight | Final Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driving Force | Population density | 0.040 | 0.040 | 0.0318 |

| DEM | 0.134 | 0.022 | 0.0585 | |

| Slope | 0.056 | 0.084 | 0.0934 | |

| Slope direction | 0.016 | 0.040 | 0.0127 | |

| Pressure | Road buffer zone | 0.031 | 0.061 | 0.0375 |

| Water buffer zone | 0.106 | 0.058 | 0.1221 | |

| State | Degree of topographic relief | 0.075 | 0.014 | 0.0208 |

| Surface cut | 0.037 | 0.016 | 0.0118 | |

| Terrain roughness | 0.024 | 0.018 | 0.0086 | |

| Vegetation cover | 0.098 | 0.046 | 0.0895 | |

| Land use type | 0.216 | 0.048 | 0.2058 | |

| Impact | Average temperatures | 0.078 | 0.042 | 0.0650 |

| Relative humidity | 0.033 | 0.024 | 0.0157 | |

| Average annual precipitation | 0.012 | 0.088 | 0.0210 | |

| Response | GDP | 0.038 | 0.249 | 0.1879 |

| Grain production per unit area | 0.006 | 0.150 | 0.0179 | |

| Management | Ecological protection policy |

| Normative layer | Indicator Layer | Area Proportion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insensitive Areas | Sensitive Areas | Moderately Sensitive Areas | Highly Sensitive Areas | Extremely Sensitive Areas | ||

| Driving Force | Population density | 95.08% | 1.25% | 1.22% | 1.27% | 1.18% |

| DEM | 52.30% | 33.81% | 10.34% | 2.97% | 0.58% | |

| Slope | 5.71% | 12.79% | 64.11% | 17.14% | 0.25% | |

| Slope direction | 15.70% | 23.05% | 18.76% | 25.77% | 16.71% | |

| Pressure | Road buffer zone | 5.61% | 2.66% | 2.57% | 2.49% | 86.67% |

| Water buffer zone | 15.35% | 18.27% | 21.73% | 20.35% | 24.29% | |

| State | Degree of topographic relief | 34.25% | 31.84% | 17.40% | 11.94% | 4.58% |

| Surface cut | 33.05% | 31.80% | 19.81% | 10.47% | 4.87% | |

| Terrain roughness | 53.17% | 28.74% | 12.33% | 5.00% | 0.76% | |

| Vegetation cover | 12.45% | 42.89% | 18.51% | 15.38% | 10.77% | |

| Land use type | 0.01% | 2.65% | 43.91% | 52.75% | 0.68% | |

| Impact | Average temperatures | 0.12% | 1.82% | 8.03% | 75.10% | 14.93% |

| Relative humidity | 17.25% | 24.15% | 19.17% | 17.31% | 22.12% | |

| Average annual precipitation | 7.42% | 14.77% | 27.30% | 30.22% | 20.29% | |

| Response | GDP | 0.12% | 5.09% | 45.83% | 47.45% | 1.51% |

| Grain production per unit area | 1.15% | 22.38% | 23.62% | 26.54% | 26.31% | |

| Integrated ecological sensitivity analysis | 12.98% | 25.38% | 24.68% | 23.27% | 13.68% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, J.; Su, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, H. Ecological Assessment Based on the InVEST Model and Ecological Sensitivity Analysis: A Case Study of Huinan County, Tonghua City, Jilin Province, China. Land 2026, 15, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010087

Tian J, Su X, Zhang K, Zhou H. Ecological Assessment Based on the InVEST Model and Ecological Sensitivity Analysis: A Case Study of Huinan County, Tonghua City, Jilin Province, China. Land. 2026; 15(1):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010087

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Jialu, Xinyi Su, Kaili Zhang, and Huidi Zhou. 2026. "Ecological Assessment Based on the InVEST Model and Ecological Sensitivity Analysis: A Case Study of Huinan County, Tonghua City, Jilin Province, China" Land 15, no. 1: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010087

APA StyleTian, J., Su, X., Zhang, K., & Zhou, H. (2026). Ecological Assessment Based on the InVEST Model and Ecological Sensitivity Analysis: A Case Study of Huinan County, Tonghua City, Jilin Province, China. Land, 15(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010087