Restoring Waterways, But for Whom? Environmental Justice, Human Rights, and the Unhoused

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Understanding Manifestations of Social and Environmental Justice

2.2. Exploring Issues Facing Unhoused People

2.3. Identifying Research Gaps

“The right to sanitation entitles everyone to have physical and affordable access to sanitation and all spheres of life that is safe, hygienic, secure, and socially and culturally acceptable, and that provides privacy and ensures dignity. Physical presence is not the same as access,”.[36]

2.4. Addressing Research Gaps

3. Results

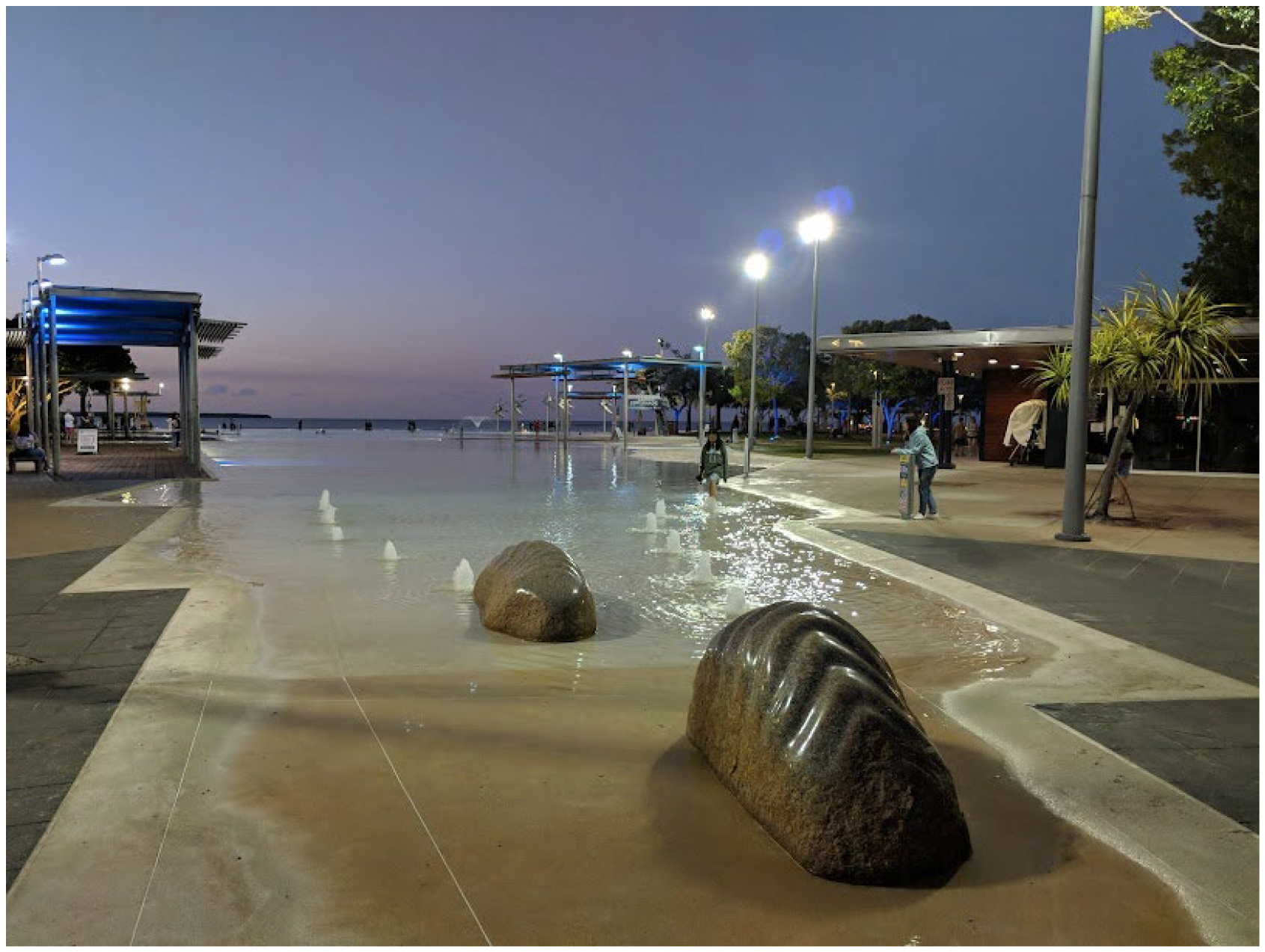

3.1. Cairns Esplanade, Queensland, Australia

3.2. CRAB Park, Vancouver, British Columbia (BC), Canada

3.3. Russian River, Sonoma County, California, USA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smardon, R.; Moran, S.; Baptiste, A.K. Revitalizing Urban Waterway’s Community Greenspace: Streams of Environmental Justice. In Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning; University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries: Amherst, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- American Society for Landscape Architecture. Environmental Justice + Landscape Architecture: A Student’s Guide, 2016. Available online: https://www.asla.org/uploadedFiles/CMS/PPNs/Landing_Pages/StudentsGuide_EnvJustice_Draft.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Przybylinski, S. San Francisco and Other Cities, Following a Supreme Court Ruling, Are Arresting More Homeless People for Living on the Streets; The Conversation: Waltham, MA, USA. 2025. Available online: https://theconversation.com/san-francisco-and-other-cities-following-a-supreme-court-ruling-are-arresting-more-homeless-people-for-living-on-the-streets-262664 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Mitchell, D. Warming Up the Bulldozers: Homelessness, Law, and the Making of Maximally Unjust Cities. Forskningsrapporter Från Kult. Inst. 2024, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechnini, L. Shifting Paradigms: Solutions for Watershed Infrastructure Financing. In Stormwater; Water Environment Federation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Colburn, G.; Shinn, M.; Batko, S.; Galvez, M.; Kushel, M. What Would It Take to End Homelessness in the United States? Hous. Policy Debate 2025, 35, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prominski, M. Design guidelines. In Research in Landscape Architecture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, C.C.; Francis, C. (Eds.) People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pable, J.; McLane, Y. Design considerations. In Homelessness and the Built Environment; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 138–167. [Google Scholar]

- French, M. Inclusive Park Design for People of All Housing Statuses: Tools for Restoring Unhoused Individuals’ Rights in Public Parks. In UCLA: The Ralph and Goldy Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies; UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1f1619sk (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Por, B.A. The Tent City as a Place of Power: Homeless Political Actors and the Making of “Public Space”. Master’s Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2014. Available online: https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/nv9355955 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Giamarino, C.D. Planning ‘Just’ Public Space: Reimagining Hostile Designs Through Do-It-Yourself Urban Design Tactics by Unhoused Communities in Los Angeles. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzholzer, S.; Duchhart, I.; Koh, J. ‘Research through designing ‘in landscape architecture. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábos, J.G.; Ryan, R.L. An introduction to greenway planning around the world. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 76, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.N. What can we learn from Julius Gyula Fábos, an admirable socio-ecological scholar-practitioner? Socio-Ecol. Pract. Res. 2022, 4, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffield, S.; Deming, M.E. Research strategies in landscape architecture: Mapping the terrain. J. Landsc. Archit. 2011, 6, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. Summary of Public Opinion on Homelessness, June, 2024. Available online: https://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Summary-of-Public-Opinion-Polling-on-Homelessness-June-2024.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Gregory, D.; Johnston, R.; Pratt, G.; Watts, M.; Whatmore, S. (Eds.) The Dictionary of Human Geography; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.; Georgiou, M.; King, A.C.; Tieges, Z.; Chastin, S. Factors influencing usage of urban blue spaces: A systems-based approach to identify leverage points. Health Place 2022, 73, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, S. Cities, creeks, and erasure: Stream restoration and environmental justice. Environ. Justice 2010, 3, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First National People of Color Summit. Principles of Environmental Justice. 1991. Available online: https://ejnet.org/ej/principles/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Smardon, R.; Moran, S.; Baptiste, A.K. Revitalizing Urban Waterway Communities: Streams of Environmental Justice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Greulich, S.; Wantzen, K.M.; Pauleit, S. Societal drivers of European water governance: A comparison of urban river restoration practices in France and Germany. Water 2017, 9, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platjouw, F.M. The green financing of ecosystem restoration. In Ecological Restoration Law; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 142–164. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.C.; Huber, C.; Skrabis, K.E.; Hoelzle, T.B. Aramework for estimating economic impacts of ecological restoration. Environ. Manag. 2024, 74, 1239–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsler, A.M.; Meerow, S.; Mell, I.C.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A. A ‘green’ chameleon: Exploring the many disciplinary definitions, goals, and forms of “green infrastructure”. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cindy, I.; Cheng, F. Words Matter, So Does the Context of History: On the Homeless and the Unhoused. Mod. Am. Hist. 2025, 8, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.H. Typologization of exclusionary design: An exploration of design interventions excluding unhoused people from urban public spaces. Des. Stud. 2024, 93, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerveny, L.K.; Baur, J.W. Homelessness and nonrecreational camping on national forests and grasslands in the United States: Law enforcement perspectives and regional trends. J. For. 2020, 118, 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Council of Hong Kong. Support Measures for the Homeless. 2021. Available online: https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/essentials-2021ise25-support-measures-for-the-homeless-in-selected-asian-places.htm (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Lakoff, G. The All New Don’t Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C.J. Walkable Cities: Revitalization, Vibrancy, and Sustainable Consumption; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mokos, J.T. Restoring the Human in the Search for Nature: Homelessness, Ecology, and the Struggle for Change; Vanderbilt University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: Nashville, TN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Homelessness and Human Rights: Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing. 2024. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-housing/homelessness-and-human-rights (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- United Nations. Summary of the Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing, Leilani Farha, A/HRC/3154. 2023. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Housing/HomelessSummary_en.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- United Nations. UN-Water: Human Rights to Water and Sanitation. 2025. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/human-rights-water-and-sanitation (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Community Solutions. Policy Brief: The Role of Sanitation and Waste Management in Local Responses to Homelessness. 2024. Available online: https://community.solutions/research-posts/policy-brief-the-role-of-sanitation-and-waste-management-in-local-responses-to-homelessness (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Portillo, L.J.A. America’s Homeless Deserve Better Access to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene|Opinion, Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative. University of California San Francisco, 3 October 2023. Available online: https://homelessness.ucsf.edu/resources/blog/americas-homeless-deserve-better-access-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-opinion (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- The Hollander. We Visited Holland’s Waterfront Homeless Camp. 30 May 2025. Available online: https://www.hollander.news/article/we-visited-hollands-waterfront-homeless-camp (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Evanston Roundtable. We Are Water—When You Are Homeless Water Becomes Gold. 27 September 2021. Available online: https://evanstonroundtable.com/2021/09/27/we-are-water-series-part-2-homeless-lakefront/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Fagan, K. Homeless People Excited but Skeptical About Idea for Waterfront Navigation Center. 14 April 2019. Available online: https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Homeless-people-excited-but-skeptical-about-idea-13764693.php (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Skinner, P.; Jones, C.F. Cairn’s foreshore development. Landsc. Archit. Aust. 2014, 141, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.; Jacups, S.; Hunter, G.; Rogerson, B. Economic evaluation of ‘Return to Country’: A Remote Australian initiative to address indigenous homelessness. Eval. Program Plan. 2016, 56, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coade, M. People experiencing homeless to receive support from the Cairns-based liaison team. The Mandarin, 3 April 2023. Available online: https://www.themandarin.com.au/216463-people-experiencing-homelessness-to-receive-support-from-cairns-based-support-team/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Prout Quicke, S.; Green, C. “Mobile (nomadic) cultures” and the politics of mobility: Insights from Indigenous Australia. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2018, 43, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibis, D. A framework for reimagining indigenous mobility and homelessness. Urban Policy Res. 2011, 29, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, A. Social Control and Homeless Encampments: Shifting the Role of Shelters Through Judicial Review. Soc. Leg. Stud. 2025, 34, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orboko, Z.; Calissi, I.; Hauka, N.; Fraser, J. The removal of Vancouver’s tent cities and their impact on Vancouver’s homeless. BCIT News, 4 December 2024. Available online: https://bcitnews.com/the-removal-of-vancouvers-tent-cities-and-their-impact-on-vancouvers-homeless/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Chiang, C. Vancouver Park Board to Close homeless encampment at CRAB Park. CBC News, 23 October 2024. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/vancouver-park-board-crab-park-closure-1.7361518 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Kulkarni, A.; Baker, R. Remaining CRAB Park Residents ordered out as Vancouver enforces eviction. CBC News, 8 November 2024. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/crab-park-eviction-nov-7-1.7376331 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Russian Riverkeeper. Homepage. 2025. Available online: https://russianriverkeeper.org/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Russian Riverkeeper. Russian River Cleanup Instructions. 2024. Available online: http://russianrivercleanup.org/cleanup-instructions/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Sonoma County. Clean River Alliance Russian River Clean Camp. 2017. Available online: https://sonomacounty.ca.gov/Main%20County%20Site/General/Sonoma/Sample%20Dept/Divisions/Housing%20Authority/Projects/A%20Service/_Documents/RFP%20HomelessImpacts%20CRACleanCampProposal.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Rosato, J. Guerneville Homeless Help Clean up Russian River. 26 February 2019. Available online: https://www.nbcbayarea.com/news/local/homeless-to-help-clean-russian-river-in-advance-of-storm/2479/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Bardach, E.; Patashnik, E.M. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving; CQ Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G. Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environ. Commun. 2010, 4, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, R. Stream restoration and the surprisingly social dynamics of science. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2016, 3, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wescoat, J.L., Jr. Introduction: Three Faces of Power in Landscape Change. In Political Economies of Landscape Change: Places of Integrative Power; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wescoat, J.L., Jr.; White, G.F. Water for Life: Water Management and Environmental Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. Mean Streets: Homelessness, Public Space, and the Limits of Capital; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Binnington, C.; Russo, A. Defensive landscape architecture in modern public spaces. Ri-Vista Res. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 19, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fine Licht, K.P. Hostile urban architecture: A critical discussion of the seemingly offensive art of keeping people away. Etikk I Praksis-Nord. J. Appl. Ethics 2017, 2, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo, L.M. The Search for Space and Dignity: Using Participatory Action Research to Explore Boundary Management Among Homeless Individuals. Ph.D. Theses, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, A.R.; Thwaites, K.; Simkins, I.M.; Mallett, R. Beyond Participation: The practical application of an empowerment process to bring about environmental and social change. Développement Hum. Handicap Et Chang. Soc. 2011, 19, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, K. Towards socially restorative urbanism: Exploring social and spatial implications for urban restorative experience. Landsc. Rev. 2011, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Site | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Cairns, Australia | Esplanade and foreshore restoration | Design has renaturalized nearshore with swimming options Amenities include drinking water, sinks, toilets, and grills for barbecuing Site remains free of hostile architecture features; unhoused people are making use of the site Laws (in Australia and Queensland) define homelessness in specific ways; policies display some awareness of concepts of mobility relative to cultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people |

| Vancouver, Canada | CRAB Park | Site specifically designed to expand waterway and greenway access among underserved populations; access was achieved and then lost Contested issues involving litigation can involve battles about scale and scope of conflict, showing that even jurisdictional elements can change outcomes Tracking the dynamics of change is complex; detail across multiple sectors of society is indispensable Narrative and policy analysis is necessary to build nuanced understanding of issues associated with perceptions, values, and policy debates regarding unhoused people; user consultations are necessary |

| Russian River, California, US | Waterfront sites, Sonoma County | Organizations restore and maintain waterways in diverse ways; simple and inexpensive methods can work Approaching work with waterways with unhoused people using the lens of trauma-informed collaboration is innovative Definition of ‘site’ can be understood flexibly and not necessarily fixed spatially; encampments may shift and relocate Organizations carrying out waterway improvements can include small nonprofits; researchers must cast a wide net to avoid overlooking them |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moran, S.; Smardon, R. Restoring Waterways, But for Whom? Environmental Justice, Human Rights, and the Unhoused. Land 2025, 14, 2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102048

Moran S, Smardon R. Restoring Waterways, But for Whom? Environmental Justice, Human Rights, and the Unhoused. Land. 2025; 14(10):2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102048

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoran, Sharon, and Richard Smardon. 2025. "Restoring Waterways, But for Whom? Environmental Justice, Human Rights, and the Unhoused" Land 14, no. 10: 2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102048

APA StyleMoran, S., & Smardon, R. (2025). Restoring Waterways, But for Whom? Environmental Justice, Human Rights, and the Unhoused. Land, 14(10), 2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102048