A Better Human Settlement Environment, Not Always a Happier Life: The Unexpected Spatial Relationships in Hunan, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Origin and Development of Human Settlements

2.2. Evaluation Systems and Methods of Human Settlements

2.3. Linking Human Settlements with Residential Satisfaction

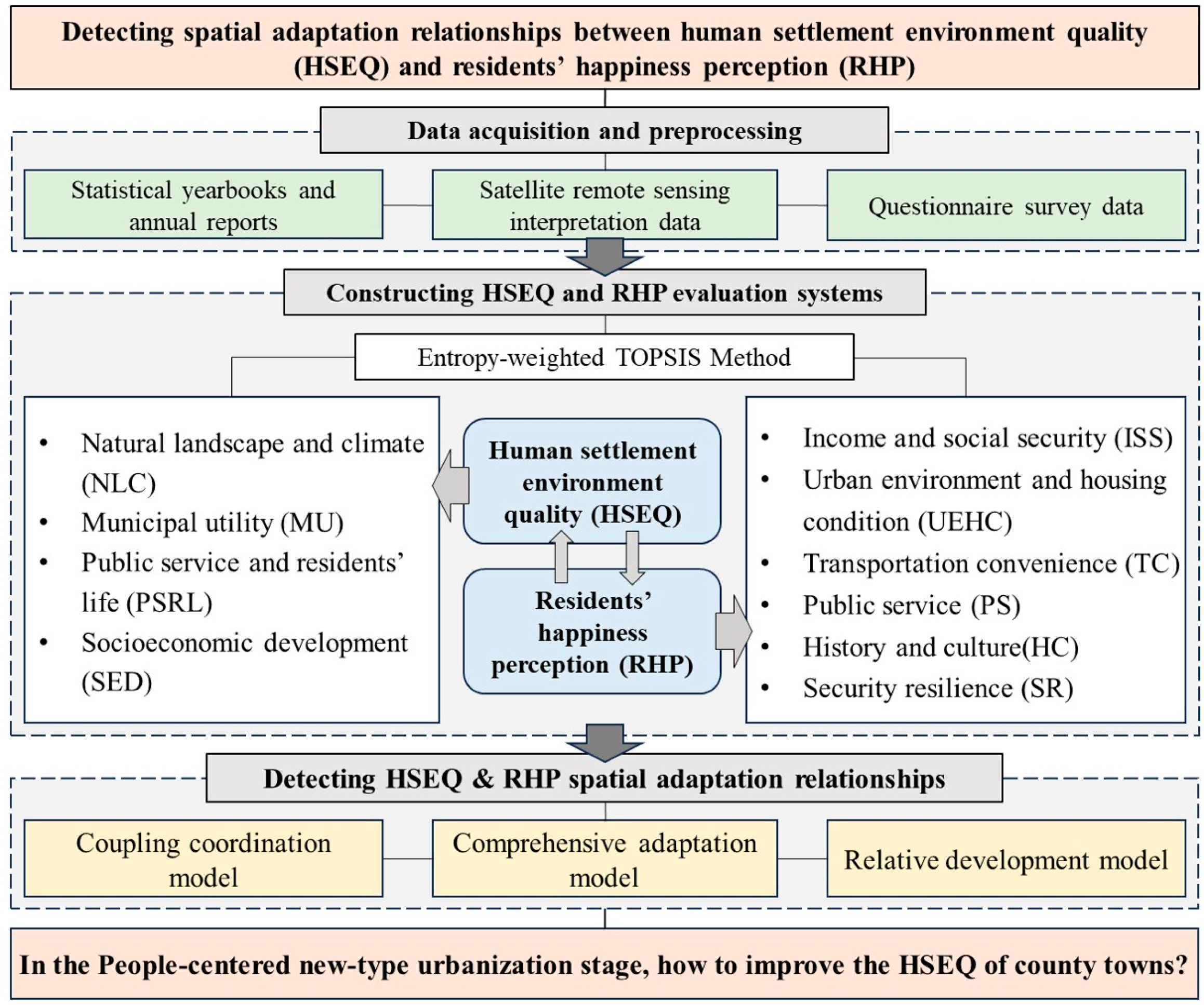

3. Study Area, Data, and Method

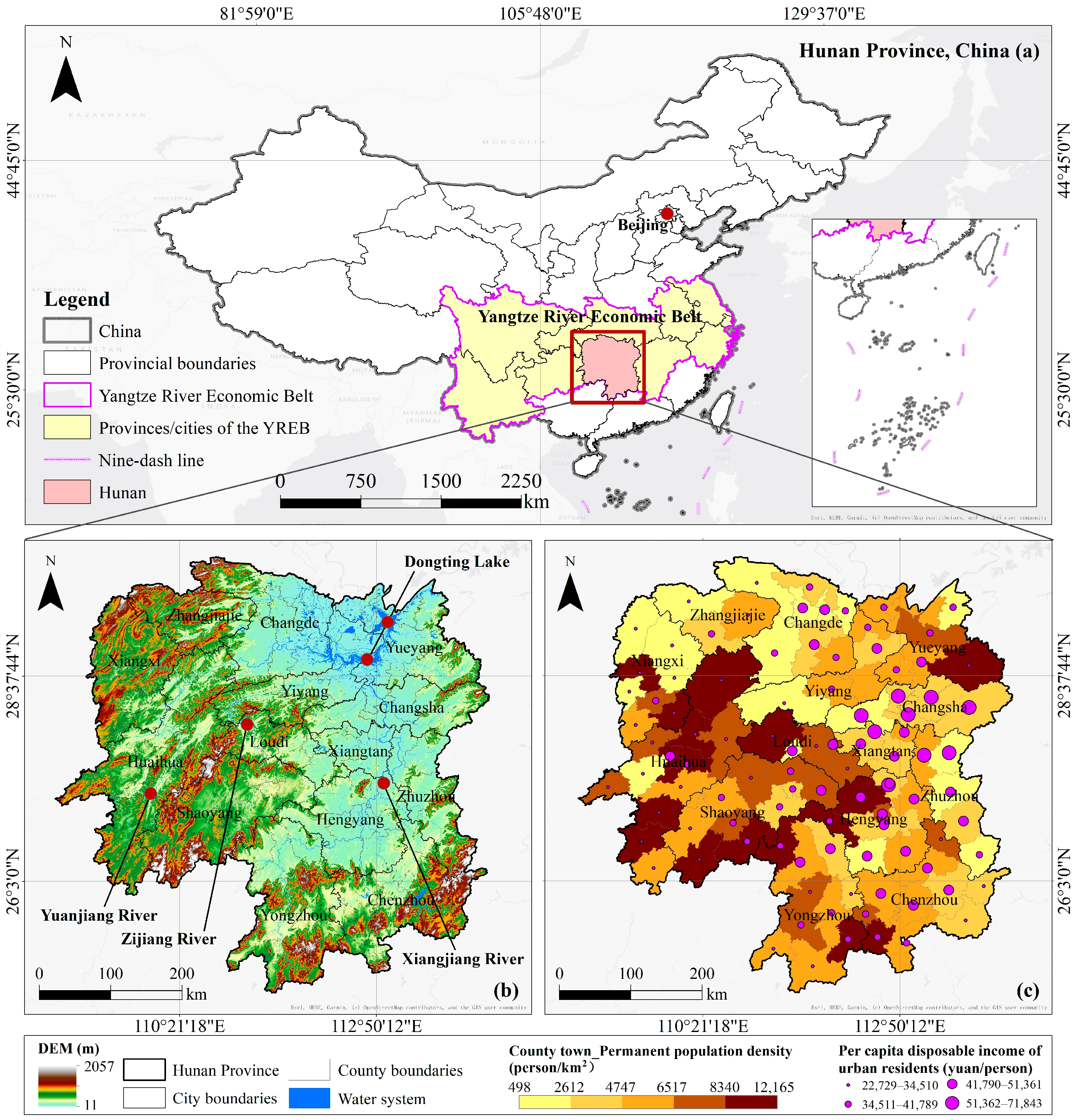

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Indicator System Construction and Data Sources

3.2.1. Evaluation Indicator Systems of HSEQ

3.2.2. Evaluation Indicator Systems of RHP

3.3. Evaluation Methods

3.3.1. Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS Model

- Step 1: Constructing the normalized evaluation matrix

- Step 2: Determining the entropy weights:

- Step 3: Constructing the weighted normalized matrix.

- Step 4: Determining the positive and negative ideal solutions.

- Step 5: Calculating the distance of each alternative from the ideal solution.

- Step 6: Calculating the comprehensive evaluation index.

3.3.2. Hotspot Analysis

3.3.3. Comprehensive Adaptation Model

- Step 1: Calculating the adaptability index. The formula is as follows:

- Step 2: Calculating the matching degree index. The formula is as follows:

3.3.4. Relative Development Model

4. Results

4.1. Human Settlement Environment Quality (HSEQ)

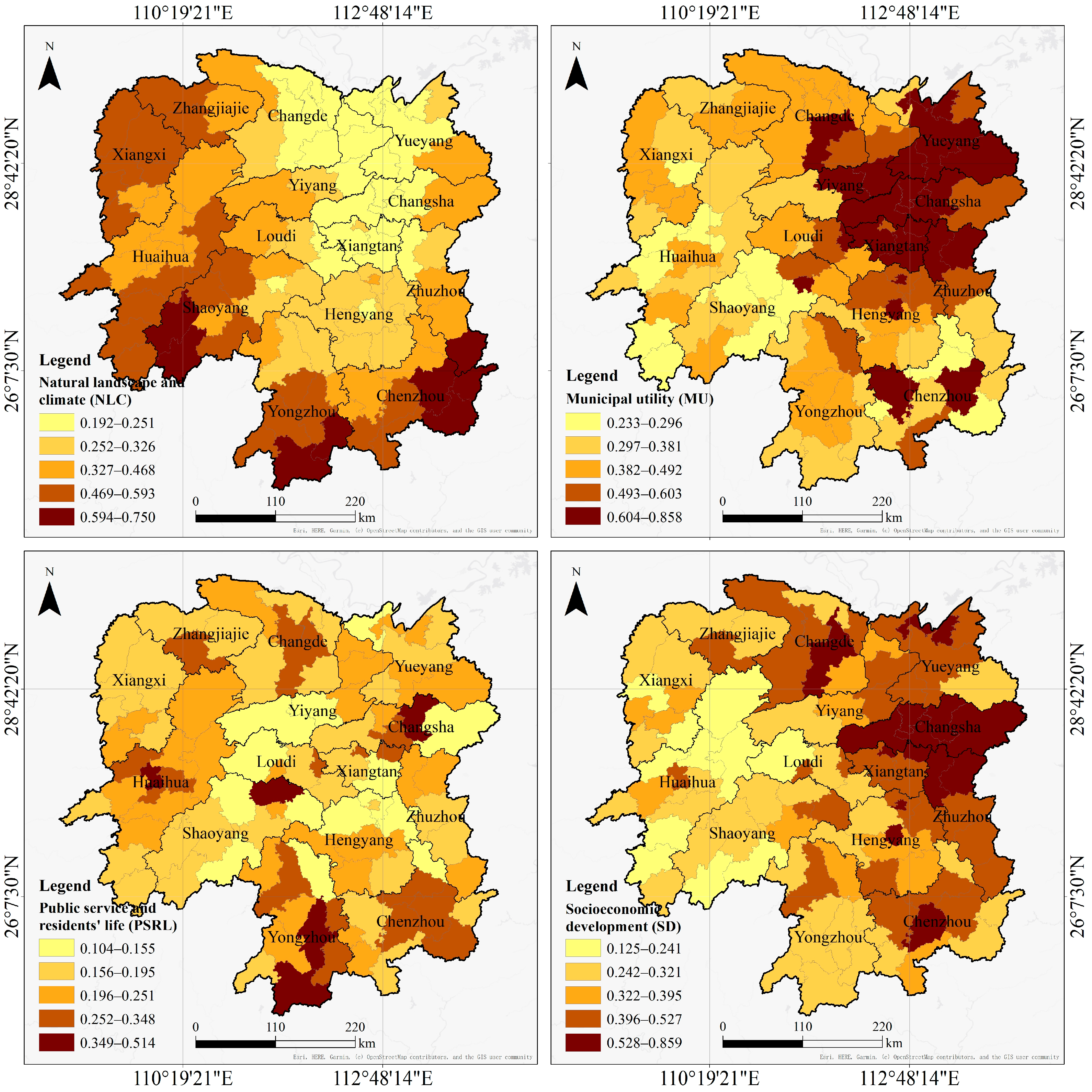

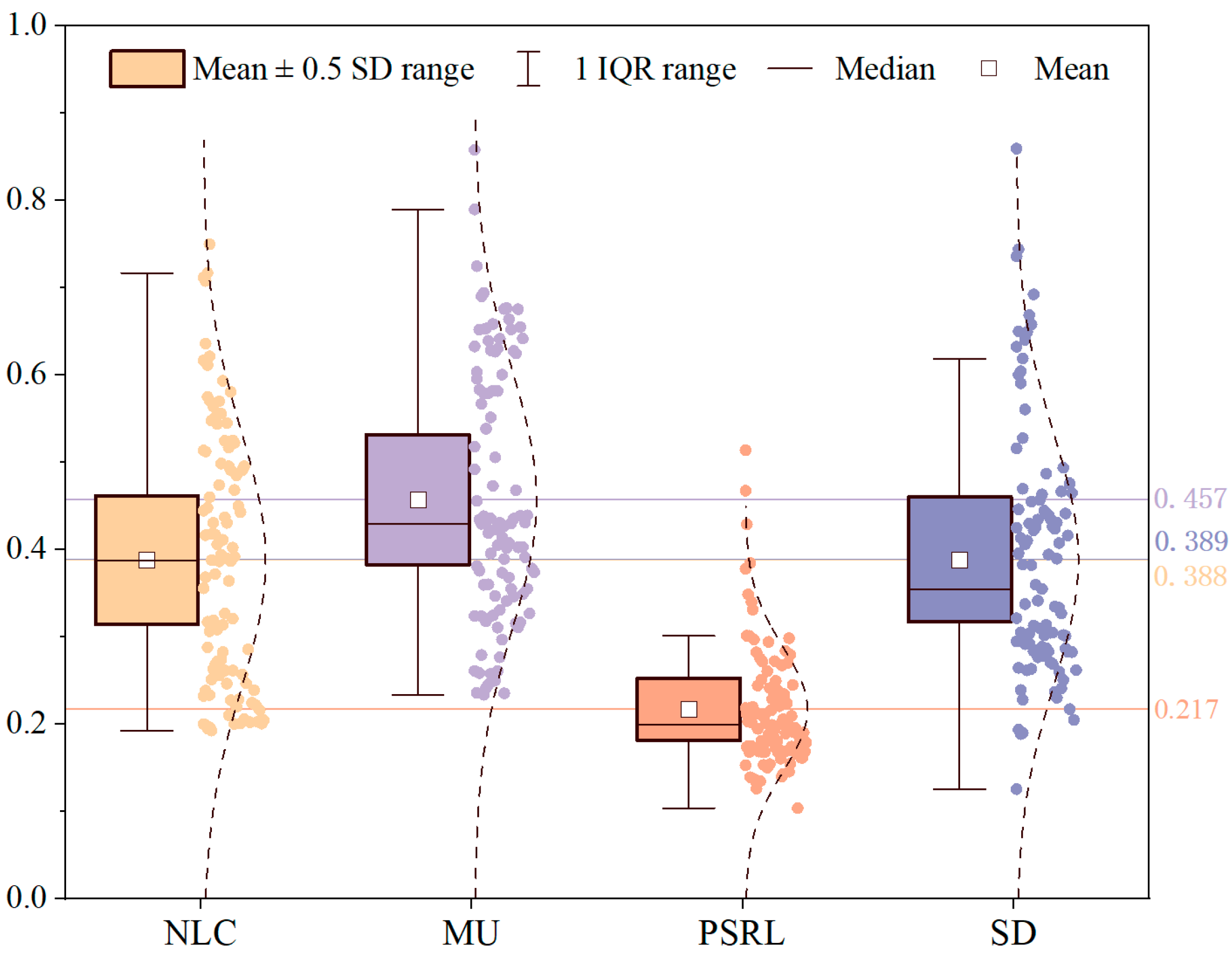

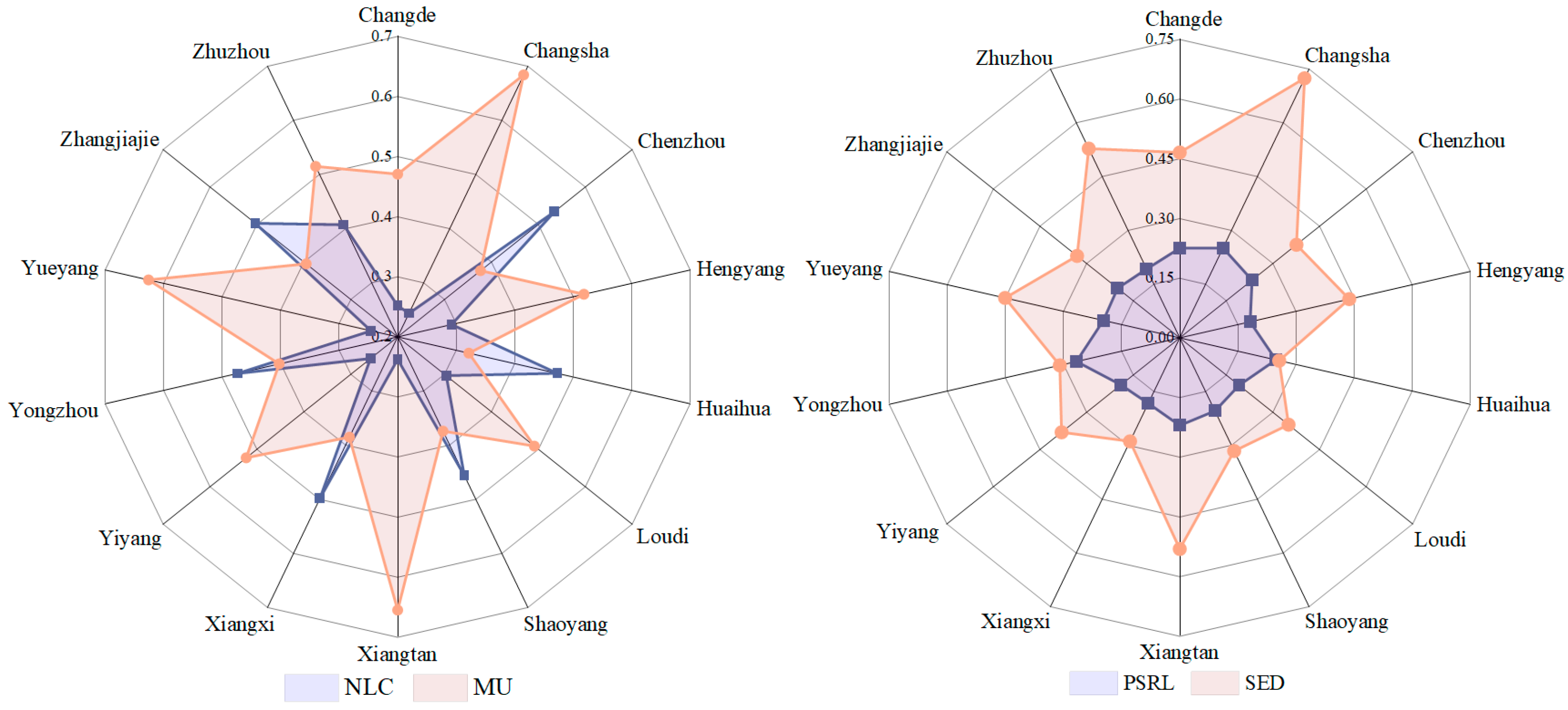

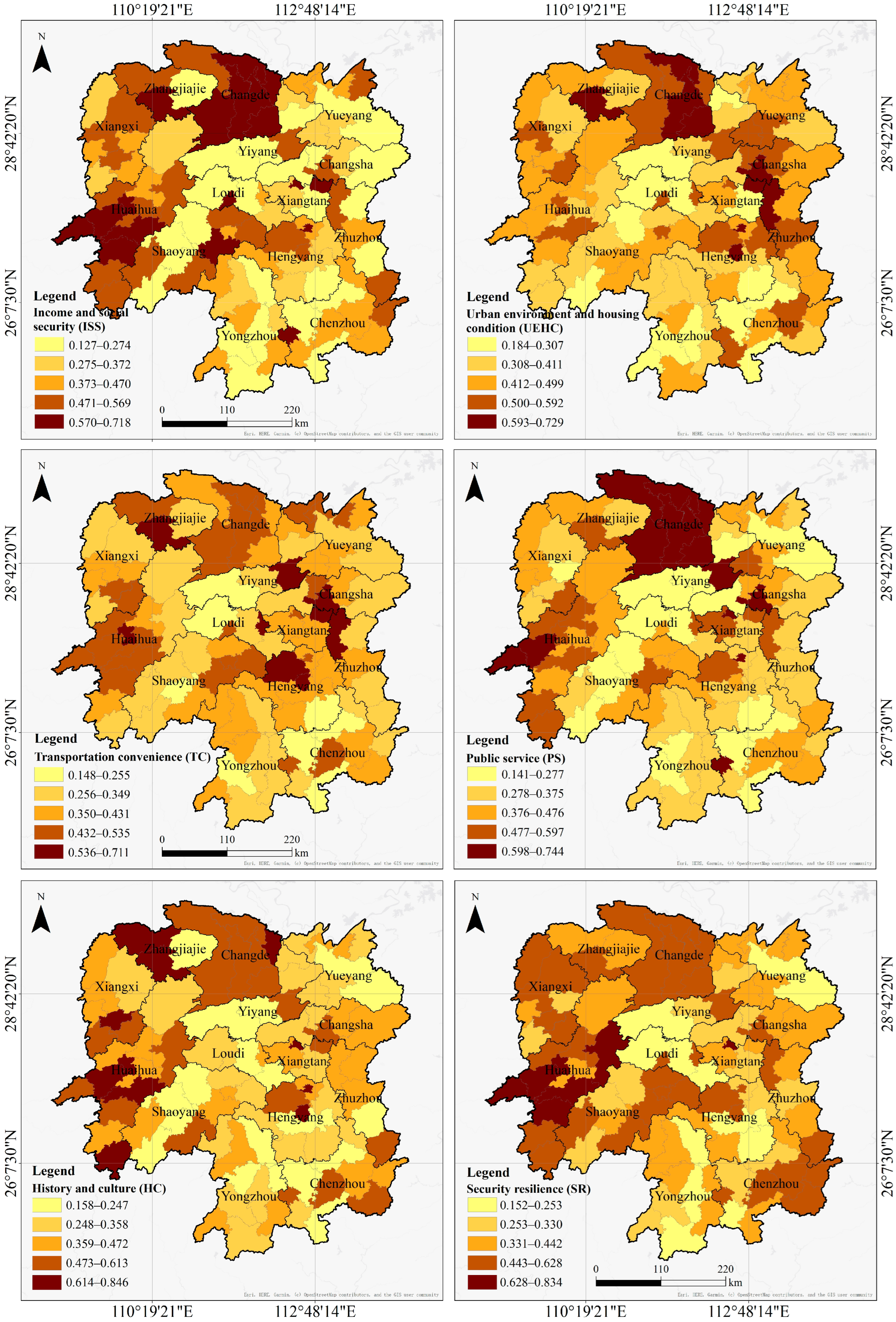

4.1.1. Distribution of HSEQ Subsystems

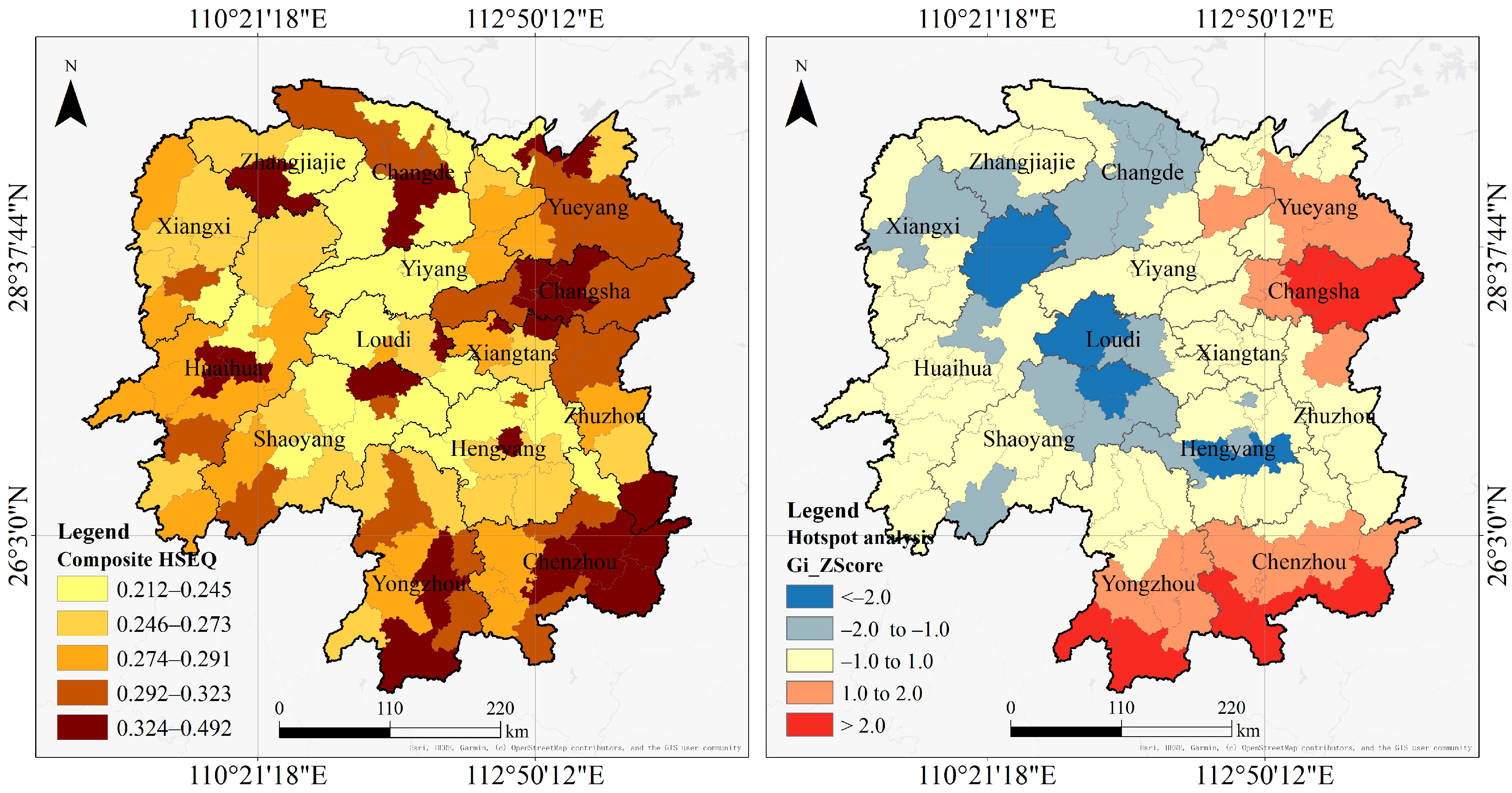

4.1.2. Distribution of Composite HSEQ

4.2. Residents’ Happiness Perception (RHP)

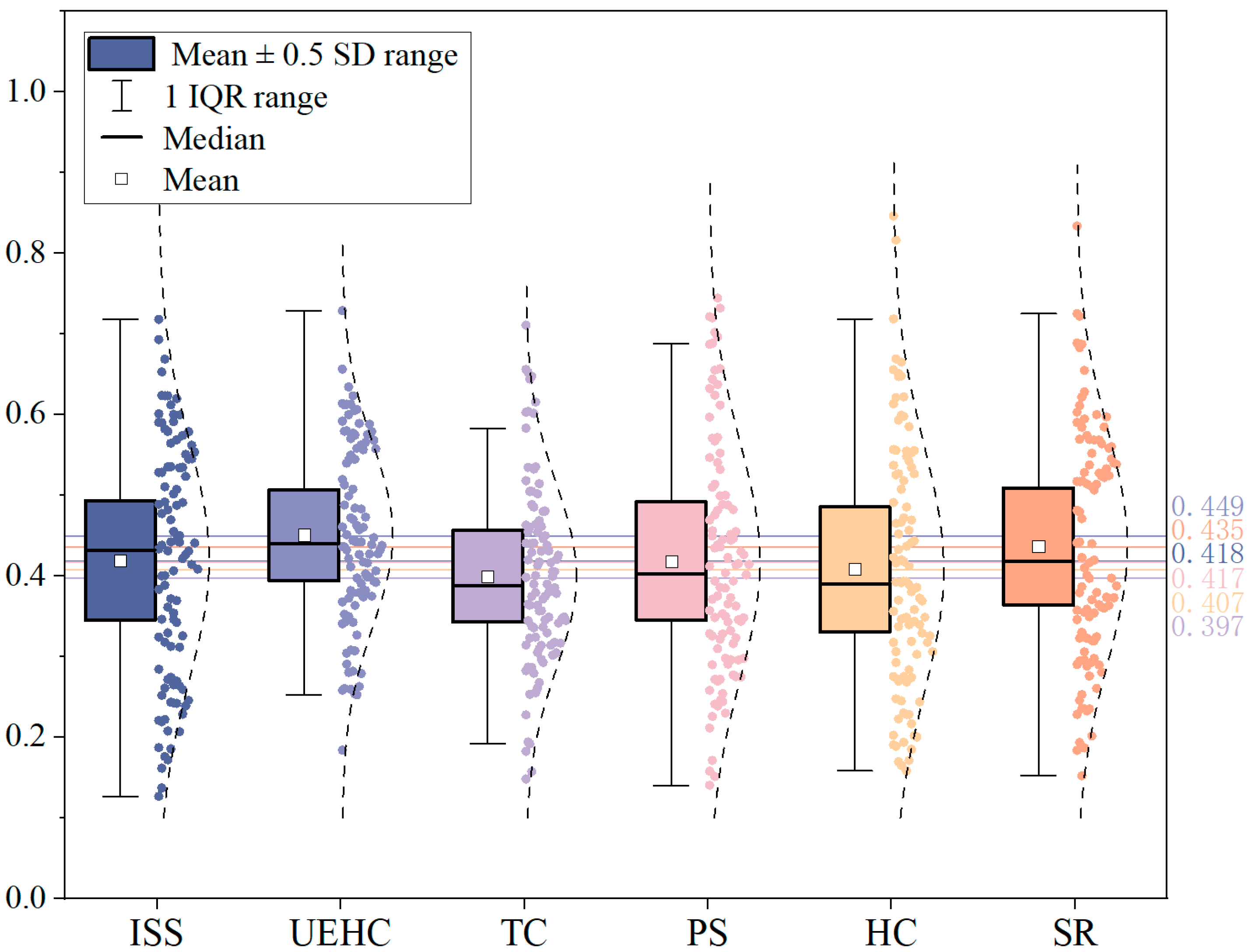

4.2.1. Distribution of RHP Subsystems

4.2.2. Distribution of Composite RHP

4.3. Adaptation Relationships Between HSEQ and RHP

4.3.1. Comprehensive Adaptation Relationships

4.3.2. Relative Development Relationships

4.3.3. Correlation Between HSEQ Indicators and Composite RHP

5. Discussions

5.1. Spatial Inadaptations and Their Causes Between HSEQ and RHP

5.2. Implications for Urbanization and Human Settlement Environment Development

5.3. Limitations and Future Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, J.; Zheng, B.; Tang, H. The Science of Rural Human Settlements: A Comprehensive Overview. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1274281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Resource spatial allocation and the basic theoretical framework of China’s New-type urbanization. Econ. Perspect. 2014, 9, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Research on the land system arrangement and peri urbanization: Division, argument and extension. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Gong, P. An “Exclusion-Inclusion” Framework for Extracting Human Settlements in Rapidly Developing Regions of China from Landsat Images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 186, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H. The path selection for the development of contemporary small and medium-sized cities. Reg. Gov. 2019, 44, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Tang, Y. Natural Environment Suitability for Human Settlements in China Based on GIS. J. Geogr. Sci. 2009, 19, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, T.; Zhang, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, D.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, G. Overview and Progress of Chinese Geographical Human Settlement Research. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1159–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Ruth, M.; He, Q.; Mirzaee, S. Comprehensive Evaluation of Trends in Human Settlements Quality Changes and Spatial Differentiation Characteristics of 35 Chinese Major Cities. Habitat Int. 2017, 70, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, D.; Shao, M. The spatial gap and bi-dimensional decomposition of high-quality development of population urbanization in China. Financ. Trade Res. 2024, 35, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lin, C.; Wu, C. Trends and planning choices after China’s urbanization rate reaching above 60%. City Plan. Rev. 2020, 44, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X. Optimization of human settlement environment and urbanization construction with county towns as the important carrier. People’s Forum 2025, 15, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Bai, Z.; Ji, S. Study on the interactive effect between urban human settlement environment and population migration. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 44, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxiadis, C.A. Ekistics, the Science of Human Settlements. Science 1970, 170, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W. Research Report on Livable Cities in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L. Introduction to Sciences of Human Settlements; China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A.; Bardhan, R. Socio-Physical Liveability through Socio-Spatiality in Low-Income Resettlement Archetypes- A Case of Slum Rehabilitation Housing in Mumbai, India. Cities 2020, 105, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S.; et al. Transforming Our World: Implementing the 2030 Agenda Through Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Tian, S.; Guan, Y.; Liu, H. Air Quality and the Spatial-Temporal Differentiation of Mechanisms Underlying Chinese Urban Human Settlements. Land 2021, 10, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Yang, X.; Wu, F. A Two-Stage System Analysis of Real and Pseudo Urban Human Settlements in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiu, C.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J.; Jin, C. Optimizing Local Climate Zones to Mitigate Urban Heat Island Effect in Human Settlements. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yi, P.; Li, W.; Gong, C. Assessment of City Sustainability from the Perspective of Multi-Source Data-Driven. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tian, S.; Tan, K.; Du, P. Human Settlement Analysis Based on Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study of Xuzhou City, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, M.; Meng, X.; Fan, Y.; Huang, Z.; Luo, E.; Pijanowski, B. The Spatio-Temporal Evolution and Transformation Mode of Human Settlement Quality from the Perspective of “production-Living-Ecological” Spaces—A Case Study of Jilin Province. Habitat Int. 2024, 145, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, Z.; Sun, C. Empirical Research on Carrying Capacity of Human Settlement System in Dalian City, Liaoning Province, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Hu, C.; Ma, L.; Chen, E.; Zhang, C.; Xia, G. Spatiotemporal Changes and Influencing Factors of the Coupled Production-Living-Ecological Functions in the Yellow River Basin, China. Land 2024, 13, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, B.; Gao, F.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z. The Human Settlement of Urban Villages in a Mountainous City of China: In-Depth Survey, Comprehensive Evaluation and Policy Implications. Habitat Int. 2025, 166, 103601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, Z.; Feng, L.; Fan, Z. Beyond Accessibility: A Multidimensional Evaluation of Urban Park Equity in Yangzhou, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Meng, J.; Ju, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, W. Assessing Community-Level Livability Using Combined Remote Sensing and Internet-Based Big Geospatial Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhong, Q.; Li, Z. Analysis of Spatial Characteristics and Influence Mechanism of Human Settlement Suitability in Traditional Villages Based on Multi-Scale Geographically Weighted Regression Model: A Case Study of Hunan Province. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, Y.; Luo, G.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yang, L. The Rural Human-Land Relationship Transition in Southwest Karst Mountainous Areas Based on Rural Population, Agricultural Production Land, and Rural Settlement Coupling. Habitat Int. 2025, 163, 103493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chu, D.; Li, Q.; Shi, Y.; Lu, L.; Bi, A. Dynamic Successive Assessment of Rural Human Settlements Environment in China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 157, 111177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Qiao, W.; Gao, H.; Li, C.; Song, X. Revealing the Correlation between the Morphology of Rural Settlement Clusters and Their Accessibility to Facilities: A Human-Centered Perspective. Habitat Int. 2025, 164, 103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Guo, Q. Evaluation of Rural Human Settlements in China Based on the Combined Model of DPSIR and PLS-SEM. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 108, 107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjia, D.; Coetzee, S. Geospatial Information Needs for Informal Settlement Upgrading—A Review. Habitat Int. 2022, 122, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Hou, L. SDGs-Oriented Evaluation of the Sustainability of Rural Human Settlement Environment in Zhejiang, China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Gao, Y.; Han, Q.; Li, L.; Dong, X.; Liu, M.; Meng, Q. Quality Evaluation and Obstacle Identification of Human Settlements in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Based on Multi-Source Data. Land 2022, 11, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Shi, C.; Zhou, G. Spatio-temporal evolution and adaptation relationship between urban scale and urban livability in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 1769–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Yang, X.; Yan, X.; Wu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q. A New Coupling Evaluation Method for Human Settlement-Environment-Energy Systems: Enhancing Residents’ Happiness. Habitat Int. 2025, 164, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y. Uncertainty Evaluation of the Coordinated Development of Urban Human Settlement Environment and Economy in Changsha City. J. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H. The Influence of Subjective and Objective Characteristics of Urban Human Settlements on Residents’ Life Satisfaction in China. Land 2021, 10, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Li, X.; Tian, S.; Li, H.; Song, Y. Influence of Human Settlements Factors on the Spatial Distribution Patterns of Traditional Villages in Liaoning Province. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, S.; Wu, J. An Approach to Urban Landscape Character Assessment: Linking Urban Big Data and Machine Learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M. Enhancing GIS Models for Sustainable Development in Human Settlements Using Intelligent IoT Infrastructure and Human-Machine Interaction. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Ding, Z.; Li, M.; Gu, J. Beyond the Horizon: Unveiling the Impact of 3D Urban Landscapes on Residents’ Perceptions through Machine Learning. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Xia, B. Study on the differences in satisfaction level on human settlements by different social stratums in Guangzhou. Urban Plan. 2013, 37, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Charoenkit, S.; Kumar, S. Environmental Sustainability Assessment Tools for Low Carbon and Climate Resilient Low Income Housing Settlements. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibem, E.O.; Amole, D. Residential Satisfaction in Public Core Housing in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, K.; Holm, E.; Strömgren, M.; Vilhelmson, B.; Westin, K. Proximity, Accessibility and Choice: A Matter of Taste or Condition? Pap. Reg. Sci. 2012, 91, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Du, X. Assessment and Determinants of Residential Satisfaction with Public Housing in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, Y.; Zheng, P.; Deng, Y.; Gu, R. The spatial characteristics and formation mechanism of urban human settlement environment renovation satisfaction. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 45, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Dang, Y.; Zhou, J. Impact of multi-scale perceptions of urban human settlements on residents’ subjective well-being: Based on the “four good” construction concept and city health examination data. Urban Plan. 2025, 49, 4–15+110. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Lu, M.; Lu, Y. Assessing the Suitability of Regional Human Settlements Environment from a Different Preferences Perspective: A Case Study of Zhejiang Province, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z. ChinaHighPM2.5: High-Resolution and High-Quality Ground-Level PM2.5 Dataset for China (2000–2023); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S. 1-km Monthly Mean Temperature Dataset for China (1901–2024); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Qin, X.; Li, Y. Satisfaction Evaluation of Rural Human Settlements in Northwest China: Method and Application. Land 2021, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, F. Contributions of the Usage and Affective Experience of the Residential Environment to Residential Satisfaction. Hous. Stud. 2016, 31, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, M. The Coordination Relationship between Urban Development and Urban Life Satisfaction in Chinese Cities—An Empirical Analysis Based on Multi-Source Data. Cities 2024, 150, 105016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanni, Z.; Khakpour, B.A.; Heydari, A. Evaluating the Regional Development of Border Cities by TOPSIS Model (Case Study: Sistan and Baluchistan Province, Iran). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 10, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, P.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, H. Study on Comprehensive Evaluation of Human Settlements Quality in Qinghai Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Fan, J. An Integrated Framework for Assessing the Multiscale Environmental Risks of Domestic Waste Management Systems in Mountainous Regions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 108, 107597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, J.K.; Getis, A. Local Spatial Autocorrelation Statistics: Distributional Issues and an Application. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Tian, S.; Bai, Z.; Liu, H. The spatio-temporal pattern evolution and driving force of the coupling coordination degree of urban human settlements system in Liaoning Province. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 39, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fan, Z.; Shen, S. Urban Green Space Suitability Evaluation Based on the AHP-CV Combined Weight Method: A Case Study of Fuping County, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Abbreviation | Weight | Nature | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural landscape and climate (NLC) (0.1624) | Topographic relief | X1 | 0.0139 | neuter | m |

| Air PM2.5 concentration | X2 | 0.0396 | - | μg/m3 | |

| Average summer temperature | X3 | 0.0715 | - | °C | |

| Average winter temperature | X4 | 0.0249 | + | °C | |

| Green coverage rate of built-up areas | X5 | 0.0125 | + | % | |

| Municipal utility (MU) (0.1355) | Road network density of built-up areas | X6 | 0.0405 | + | km/km2 |

| Road lighting rate of built-up areas | X7 | 0.0123 | + | % | |

| Residential water price | X8 | 0.0185 | - | CNY/m3 | |

| Residential natural gas price | X9 | 0.0507 | - | CNY/m3 | |

| Wastewater treatment rate | X10 | 0.0086 | + | % | |

| Household waste disposal rate | X11 | 0.0049 | + | % | |

| Public service and residents’ life (PSRL) (0.5285) | Per capita residential land area | X12 | 0.0302 | + | km2/10,000 person |

| Per capita urban park green space area | X13 | 0.0217 | + | m2 | |

| Per capita greenway length | X14 | 0.1186 | + | km/10,000 person | |

| Per capita commercial and service facility land area | X15 | 0.0499 | + | km2/10,000 person | |

| Parking spaces per 10,000 people | X16 | 0.1181 | + | person/10,000 person | |

| Medical institution quota per 10,000 people | X17 | 0.0183 | + | person/10,000 person | |

| Health technician quota per 10,000 people | X18 | 0.0332 | + | person/10,000 person | |

| Hospital bed quota per 10,000 people | X19 | 0.0257 | + | person/10,000 person | |

| Secondary school quota per 1000 students | X20 | 0.0381 | + | person/1000 person | |

| Primary school quota per 1000 students | X21 | 0.0471 | + | person/1000 person | |

| Secondary school teacher quota per 1000 students | X22 | 0.0331 | + | person/1000 person | |

| Primary school teacher quota per 1000 students | X23 | 0.0247 | + | person/1000 person | |

| Socioeconomic development (SD) (0.1421) | Population density of built-up areas | X24 | 0.0242 | - | person/km2 |

| Per capita GDP | X25 | 0.0325 | + | CNY 10,000 | |

| Per capita urban-town disposable income | X26 | 0.0343 | + | CNY 10,000 | |

| Per capita total retail sales of consumer goods | X27 | 0.0399 | + | CNY 10,000 | |

| Urban housing prices | X28 | 0.0056 | - | CNY | |

| Proportion of secondary and tertiary industries | X29 | 0.0056 | + | % |

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators |

|---|---|

| Income and social security (ISS) (0.1580) | X1 Total household income (0.0216); X2 Household expenditure structure (0.0281); X3 Tourism consumption expenditure (0.0179); X4 Employment (0.0156); X5 Social security contributions * (0.0247); X6 Regular company health checkups (0.0142); X7 Rights of migrant workers * (0.0228); X8 Construction of an age-friendly city * (0.0131) |

| Urban environment and housing condition (UEHC) (0.1576) | X9 Integration of urban and natural landscapes (0.0167); X10 Housing area (0.0118); X11 Housing type (0.0191); X12 Household energy type (0.0154); X13 Household appliance type * (0.0069); X14 Residential sound insulation (0.0054); X15 Community elevator configuration (0.0208); X16 Community parking configuration (0.0153); X17 Residential winter sunlight (0.0114); X18 Smart home system * (0.0240); X19 Property services (0.0109) |

| Transportation convenience (TC) (0.2250) | X20 Residential road quality (0.0212); X21 Convenient transportation facilities * (0.0187); X22 Intercity transportation (0.0175); X23 Daily travel (0.0153); X24 One-way commute to work/school (0.0099); X25 To the city center (0.0336); X26 Picking up and dropping off children at school (0.0133); X27 School dismissal traffic congestion (0.0158); X28 Parking near schools (0.0187); X29 Public transportation (0.0157); X30 Taxi transportation (0.0154); X31 Green and low-carbon travel (0.0152); X32 Intelligent transportation system * (0.0147) |

| Public service (PS) (0.2090) | X33 Convenient living circle * (0.0187); X34 Maintenance of community public facilities (0.0197); X35 Community public health service center (0.0142); X36 Fresh food supermarket (0.0180); X37 Park (0.0212); X38 Express delivery station (0.0156); X39 Public toilet (0.0146); X40 Rest facilities (0.0228); X41 Activity area for the elderly and children * (0.0211); X42 Medical treatment (0.0173); X43 Attending high-quality schools (0.0092); X44 Elderly care options * (0.0165) |

| History and culture (HC) (0.1058) | X45 Historical and cultural heritage (0.0177); X46 Intangible cultural heritage inheritance and folk custom protection * (0.0127); X47 Traditional food and local specialties * (0.0183); X48 Historic districts and buildings (0.0102); X49 Ethnic cultural value * (0.0225); X50 Tourism highlights * (0.0244) |

| Safety resilience (SR) (0.1446) | X51 Safety risks experienced (0.0186); X52 Emergency shelters (0.0203); X53 Campus traffic safety design (0.0189); X54 Community fire lanes (0.0161); X55 Community safety governance activities * (0.0232); X56 Food and environmental safety * (0.0223); X57 Ecological governance and maintenance * (0.0253) |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Percentage | Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 50.8 | Household registration type | Urban-town | 49.6 |

| Female | 49.2 | Village | 50.4 | ||

| Age | 24 and under | 22.8 | Profession | Government/Public Institution Worker | 5.4 |

| 25–34 | 28.3 | Student | 14.2 | ||

| 35–44 | 20.2 | Soldier | 0.3 | ||

| 45–54 | 12.5 | Researcher | 0.7 | ||

| 55–64 | 10.3 | Teacher | 3.0 | ||

| 65 and above | 5.9 | Individual industrial and commercial household | 10.8 | ||

| Educational level | Junior high school and below | 25.2 | Farmer | 17.9 | |

| High School/Secondary School | 22.8 | Workman | 19.6 | ||

| College | 16.4 | Retiree | 3.1 | ||

| Undergraduate | 30.3 | Freelancer | 7.6 | ||

| Master and above | 5.3 | Others | 18.4 | ||

| HSEQ Subsystems | Maximum | Minimum | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLC | 0.750 | 0.192 | 0.388 | 0.388 | 0.147 |

| MU | 0.858 | 0.233 | 0.457 | 0.429 | 0.148 |

| PSRL | 0.514 | 0.104 | 0.217 | 0.200 | 0.071 |

| SD | 0.859 | 0.125 | 0.389 | 0.355 | 0.143 |

| HSEQ Level | Total Number | Names of CLUAs |

|---|---|---|

| Low level (0.212–0.245) | 22 | Anren County, Huarong County, Shuangfeng County, Shaoyang County, Xinhua County, Lixian County, Longhui County, Shaodong City, Anhua County, Hengyang County, Hengdong County, Anxiang County, Chenxi County, Hanshou County, Luxi County, Taojiang County, Hengshan County, Cili County, Taoyuan County, Wugang City, Qidong County, Leiyang City |

| Relatively low level (0.246–0.273) | 20 | Baojing County, Xinning County, Chaling County, Dongkou County, Lianyuan City, Guzhang County, Xiangtan County, Dong’an County, Changning City, Nanxian County, Yongshun County, Hengnan County, Qiyang City, Jiangyong County, Sangzhi County, Yuanling County, Jingzhou Miao and Dong Autonomous County, Linxiang City, Huayuan County, Fenghuang County |

| Medium level (0.274–0.291) | 20 | Youxian County, Xupu County, Jiahe County, Linwu County, Yuanjiang City, Xiangxiang City, Daoxian County, Xiangyin County, Xinhuang Dong Autonomous County, Suining County, Tongdao Dong Autonomous County, Hongjiang City, Lengshuijiang City, Mayang Miao Autonomous County, Zhijiang Dong Autonomous County, Guiyang County, Longshan County, Yiyang urban area *, Shuangpai County, Miluo City |

| Relatively high level (0.292–0.323) | 19 | Jishou City, Yueyang County, Huitong County, Shaoyang urban area *, Shimen County, Liuyang City, Ningxiang City, Yizhang County, Yongxing County, Pingjiang County, Yongzhou urban area *, Nanyue urban area *, Zhuzhou urban area *, Chengbu Miao Autonomous County, Xintian County, Linli County, Jinshi City, Lanshan County, Liling City |

| High level (0.324–0.492) | 20 | Hengyang urban area *, Zhangjiajie urban area *, Wangcheng District *, Guidong County, Loudi urban area *, Yueyang urban area *, Yanling County, Xiangtan urban area *, Chenzhou urban area *, Shaoshan City, Changde urban area *, Zhongfang County, Rucheng County, Huaihua urban area *, Zixing City, Changsha urban area *, Changsha County, Jianghua Yao Autonomous County, Ningyuan County, Xinshao County |

| RHP Subsystems | Maximum | Minimum | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISS | 0.718 | 0.127 | 0.418 | 0.431 | 0.147 |

| UEHC | 0.729 | 0.184 | 0.449 | 0.438 | 0.112 |

| TC | 0.711 | 0.148 | 0.397 | 0.393 | 0.111 |

| PS | 0.744 | 0.141 | 0.417 | 0.395 | 0.148 |

| HC | 0.846 | 0.158 | 0.407 | 0.381 | 0.152 |

| SR | 0.834 | 0.152 | 0.435 | 0.409 | 0.147 |

| RHP Level | Total Number | Names of CLUAs |

|---|---|---|

| Low level (0.165–0.286) | 16 | Anhua County, Guiyang County, Yongxing County, Lianyuan City, Leiyang City, Xinhua County, Daoxian County, Yizhang County, Pingjiang County, Taojiang County, Ningyuan County, Chengbu Miao Autonomous County, Dongkou County, Longhui County, Yueyang County, Qiyang City |

| Relatively low level (0.287–0.367) | 20 | Jianghua Yao Autonomous County, Wugang City, Yuanjiang City, Hengnan County, Ningxiang City, Shuangfeng County, Xiangtan County, Xintian County, Chaling County, Cili County, Nanxian County, Anren County, Liling City, Linwu County, Guzhang County, Liuyang City, Shuangpai County, Lanshan County, Changning City, Jiangyong County |

| Medium level (0.368–0.438) | 20 | Fenghuang County, Qidong County, Yongzhou urban area *, Hengdong County, Hengshan County, Yuanling County, Wangcheng District *, Longshan County, Yongshun County, Dongan County, Linxiang City, Miluo City, Youxian County, Huarong County, Suining County, Changsha County, Xiangyin County, Xiangxiang City, Huayuan County, Guidong County |

| Relatively high level (0.439–0.528) | 23 | Xinshao County, Zhongfang County, Yueyang urban area *, Chenzhou urban area *, Jingzhou Miao and Dong Autonomous County, Chenxi County, Rucheng County, Shaodong City, Yanling County, Xinning County, Tongdao Dong Autonomous County, Zixing City, Shaoyang urban area *, Sangzhi County, Xupu County, Baojing County, Mayang Miao Autonomous County, Lengshuijiang City, Shaoyang County, Jishou City, Luxi County, Shimen County, Loudi urban area * |

| High level (0.529–0.658) | 22 | Huitong County, Hanshou County, Xinhuang Dong Autonomous County, Zhuzhou urban area *, Hengyang County, Hengyang urban area *, Jiahe County, Xiangtan urban area *, Taoyuan County, Yiyang urban area *, Anxiang County, Linli County, Changde urban area *, Lixian County, Nanyue District *, Jinshi City, Zhijiang Dong Autonomous County, Zhangjiajie urban area *, Shaoshan City, Changsha urban area *, Hongjiang City, Huaihua urban area * |

| HSEQ and RHP Adaptation Level | Total Number | Names of CLUAs |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely low adaptation (<0.5) | 13 | Ningyuan County, Lixian County, Yongxing County, Jianghua Yao Autonomous County, Anxiang County, Shaoyang County, Hengyang County, Chengbu Miao Autonomous County, Yizhang County, Pingjiang County, Guiyang County, Taoyuan County, Hanshou County |

| Low adaptation (0.5–0.6) | 16 | Luxi County, Shaodong City, Yueyang County, Huarong County, Xintian County, Ningxiang City, Liling City, Daoxian County, Chenxi County, Baojing County, Lanshan County, Xinning County, Liuyang City, Wangcheng District *, Changsha County, Lianyuan City |

| Basic adaptation (0.6–0.7) | 42 | Anren County, Hongjiang City, Jiahe County, Hengdong County, Yuanjiang City, Yongzhou urban area *, Sangzhi County, Leiyang City, Shuangpai County, Shuangfeng County, Hengshan County, Anhua County, Xinshao County, Qiyang City, Zhijiang Dong Autonomous County, Zhongfang County, Xupu County, Xinhuang Dong Autonomous County, Guidong County, Dongkou County, Chenzhou urban area *, Yueyang urban area *, Hengnan County, Rucheng County, Linwu County, Qidong County, Jingzhou Miao and Dong Autonomous County, Yiyang urban area *, Longhui County, Taojiang County, Dong’an County, Zixing City, Xinhua County, Yanling County, Longshan County, Lengshuijiang City, Yongshun County, Cili County, Huayuan County, Miluo City, Xiangtan County, Mayang Miao Autonomous County |

| Moderate adaptation (0.7–0.8) | 27 | Nanxian County, Tongdao Dong Autonomous County, Wugang City, Changning City, Nanyue District *, Guzhang County, Linxiang City, Huitong County, Fenghuang County, Chaling County, Jishou City, Yuanling County, Youxian County, Jiangyong County, Jinshi City, Shimen County, Xiangyin County, Xiangxiang City, Linli County, Suining County, Zhangjiajie urban area *, Shaoyang urban area *, Zhuzhou urban area *, Loudi urban area *, Hengyang urban area *, Shaoshan City, Xiangtan urban area * |

| High adaptation (0.8–1) | 3 | Changde urban area *, Huaihua urban area *, Changsha urban area * |

| Relative Development Relationships Between HSEQ and RHP | Total Number | Names of CLUAs |

|---|---|---|

| RHP significantly ahead (<0.6) | 33 | Lixian County, Anxiang County, Hengyang County, Taoyuan County, Hanshou County, Shaoyang County, Hongjiang City, Luxi County, Zhijiang Dong Autonomous County, Jiahe County, Yiyang urban area *, Shaodong City, Xinhuang Dong Autonomous County, Nanyue District *, Huarong County, Baojing County, Jinshi City, Chenxi County, Xinning County, Linli County, Zhangjiajie urban area *, Huitong County, Zhuzhou urban area *, Sangzhi County, Shaoshan City, Xupu County, Shimen County, Hengyang urban area *, Lengshuijiang City, Mayang Miao Autonomous County, Huaihua urban area *, Jishou City, Changde urban area* |

| RHP relatively ahead (0.6–0.9) | 46 | Jingzhou Miao and Dong Autonomous County, Hengdong County, Tongdao Dong Autonomous County, Xiangtan urban area *, Hengshan County, Anren County, Shaoyang urban area *, Qidong County, Huayuan County, Loudi urban area *, Xiangxiang City, Dong’an County, Changsha urban area *, Xiangyin County, Yongshun County, Linxiang City, Youxian County, Shuangfeng County, Yuanling County, Suining County, Changning City, Miluo City, Longshan County, Jiangyong County, Fenghuang County, Yanling County, Guzhang County, Cili County, Yueyang urban area *, Guidong County, Chenzhou urban area *, Chaling County, Yongzhou urban area *, Zhongfang County, Nanxian County, Linwu County, Xiangtan County, Longhui County, Shuangpai County, Wugang City, Wangcheng District *, Zixing City, Rucheng County, Liuyang City, Hengnan County, Lanshan County |

| Basically balanced (0.9–1.1) | 12 | Xinhua County, Taojiang County, Yuanjiang City, Dongkou County, Qiyang City, Liling City, Xintian County, Changsha County, Ningxiang City, Leiyang City, Yueyang County, Lianyuan City |

| HSEQ relatively ahead (1.1–1.4) | 5 | Xinshao County, Dao County, Chengbu Miao Autonomous County, Yizhang County, Pingjiang County |

| HSEQ significantly ahead (>1.4) | 5 | Anhua County, Yongxing County, Guiyang County, Jianghua Yao Autonomous County, Ningyuan County |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, D.; Shi, L.; Liang, Z.; Lou, Z. A Better Human Settlement Environment, Not Always a Happier Life: The Unexpected Spatial Relationships in Hunan, China. Land 2026, 15, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010021

Tang D, Shi L, Liang Z, Lou Z. A Better Human Settlement Environment, Not Always a Happier Life: The Unexpected Spatial Relationships in Hunan, China. Land. 2026; 15(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Disha, Lei Shi, Zhengyuan Liang, and Zeming Lou. 2026. "A Better Human Settlement Environment, Not Always a Happier Life: The Unexpected Spatial Relationships in Hunan, China" Land 15, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010021

APA StyleTang, D., Shi, L., Liang, Z., & Lou, Z. (2026). A Better Human Settlement Environment, Not Always a Happier Life: The Unexpected Spatial Relationships in Hunan, China. Land, 15(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010021