Unveiling Paradoxes: A Multi-Source Data-Driven Spatial Pathology Diagnosis of Outdoor Activity Spaces for Aging in Place in Beijing’s “Frozen Fabric” Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Spatial Provision: A Full-Chain Examination

1.2. Spatial Practice: Multi-Actor Collaboration

1.3. Spatial Perception: Multi-Layered Subjective Experience

1.4. Spatial Pathology Framework

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample

2.2. Data Collection and Analytical Workflow

- Three Baseline Data Streams A1: Spatial Supply indicators including Location Convenience Index (Iloca), Openness Index (Iopen), Facility Adequacy (zk), Supply Balance (Balance), Activity-Place Index (AP), and Spatial Quality Index (SQI); A2: Spatial Practice indicators including Activity Intensity (Intensity), Peak Hour Ratio (PHR), Time Concentration Index (TCI), and Multi-Visit Rate (MVR); A3: Spatial Perception indicators including six-dimension satisfaction scores (d) and Composite Satisfaction Score (CS).

- Three Diagnostic Paradox Pathways B1: Suppl vs. Practice mismatch via Functional Failure Index (FFI) and Efficacy Loss Rate (ELR); B2: Supply vs. Perception mismatch via Value-Quality Gap Index (VQGI)and Weighted Paradox Intensity (WPI); B3: Practice vs. Perception decoupling via correlation and regression residual analysis; B4: Integrated ternary analysis via Total Paradox Index (TPI). Each indicator entry in Table 1 specifies its formula, normalization method, threshold classification (e.g., quartile-based cutoffs, coefficient of variation benchmarks), and applicable references. Readers are directed to refer to Table 1 continuously throughout Section 2.2, Section 3, Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3 and Section 3.4 for precise operational definitions of all abbreviated indices.

- Spatial Supply Data: Through field surveys and open geographic data, we conducted quantitative audits of each community’s outdoor environment. Recorded indicators include location convenience (Iloca), site openness (Iopen, facility completeness (zk, e.g., counts of seating, toilets, exercise equipment), and supply balance (balance. We also measured the total number and area of spaces available for elderly activities in each community, calculating service density and an Activity-Place (AP Index to gauge the relative sufficiency of dedicated senior activity areas. Based on these measures, we developed a composite Spatial Quality Index (SQI on a 0–100 scale, where higher scores indicate stronger environmental support for older residents.

- Spatial Practice Data: We employed systematic behavioral observation (based on SOPARC protocols) to capture actual usage patterns of outdoor spaces. On clear, rain-free weekdays and weekends, the period 7:00–18:00 was divided into three daily time segments for repeated observational sweeps. Over two consecutive weeks, this yielded 41,924 recorded instances of elderly activity. While Beijing is characterized by significant seasonal temperature variations which undoubtedly influence absolute levels of outdoor activity, the specific two-week observation window was strategically selected during mid-October. This transitional period offers temperate climatic conditions historically conducive to peak outdoor space utilization by older adults, avoiding the confounding inhibitory effects of extreme winter cold or intense summer heat common in Beijing’s climate [101]. Furthermore, methodological precedents in behavioral mapping suggest that intensive, short-term observational windows during such optimal activity periods are sufficient to capture stable, recurrent patterns of spatial usage and the fundamental mechanisms of environment–behavior interactions, even in the absence of longitudinal seasonal data [102,103]. The research focus here is on the structural relationships between spatial features and behavioral types, which are hypothesized to remain consistent across seasons, albeit with varying frequency. From these data, the average daily activity intensity per community was calculated as an indicator of spatial utilization. We also analyzed temporal usage patterns: the Peak Hour Ratio (PHR—the ratio of the maximum hourly user count to the daily average—was computed to assess whether usage was overly concentrated at certain times; the Time Concentration Index (TCI was calculated to characterize the balance of activity across morning, midday, and evening periods. In addition, a Multi-Visit Rate (MVR was determined to reflect the proportion of repeat visitors, indicating the spaces’ sustained appeal to community seniors.

- Spatial Perception Data: Questionnaire surveys and interviews were conducted to assess residents’ subjective satisfaction with their community’s outdoor environment. The survey included six evaluation dimensions: spatial adequacy, accessibility, facilities and equipment, barrier-free design and safety, environmental comfort, and neighborhood life. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, and overall satisfaction was scored on a 100-point scale as the Composite Satisfaction Score (CS We received 354 valid questionnaires. Reliability and validity tests indicated good psychometric properties: Cronbach’s α for all dimension scales exceeded 0.70, the KMO sampling adequacy for the dataset was above 0.60, and Bartlett’s sphericity test was significant, confirming internal consistency and construct validity. Based on the survey results, we calculated each community’s average scores for the six dimensions and the overall satisfaction score, providing baseline levels of subjective perception. Additionally, open-ended responses and follow-up interview notes from representative respondents were reviewed to contextualize the quantitative findings with qualitative insights.

- Supply–Demand Functional Failure Paradox (Spatial Supply vs. Actual Usage): This pathway examines how well a community’s objective spatial supply aligns with its actual utilization. We introduce a Functional Failure Index (FFI to quantify the degree of functional oversupply or undersupply, defined as the standardized supply quality (SQI minus the standardized usage intensity. To further quantify unused spatial potential, an Efficacy Loss Rate (ELR was defined as the proportion of supply capacity remaining unused (a percentage of total supply, indicating underutilization). In addition, we compared matching indicators on the supply and usage sides point-by-point to calculate specific mismatch values, pinpointing which functional elements (e.g., seating, exercise equipment) were redundant or deficient at a granular level. This combination of measures diagnoses the functional alignment between each community’s physical supply and its actual usage.

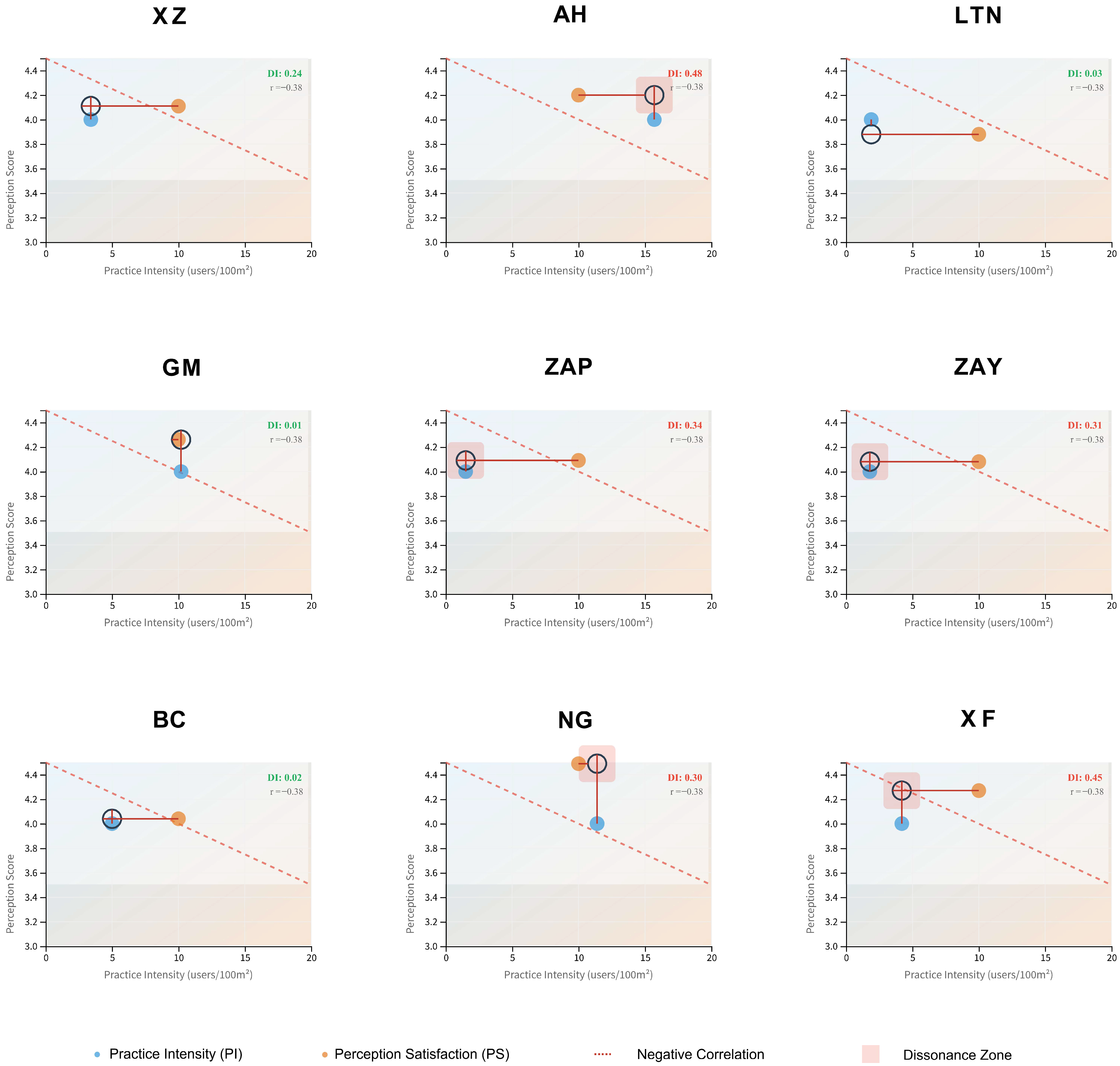

- Practice–Perception Decoupling Paradox (Actual Use vs. Subjective Perception): This pathway assesses the consistency between seniors’ observed behavior and their reported satisfaction. Methodologically, we first calculate the Spearman rank correlation coefficient between the nine communities’ usage intensity rankings and satisfaction rankings to gauge the overall association between usage and satisfaction. We then examine the rank differences for individual communities. To quantify each community’s deviation, we define a Perception–Utilization Gap as the standardized satisfaction score minus the standardized usage intensity. This value reflects whether a community’s subjective evaluation is higher or lower than would be expected from its objective usage level. We also constructed a simple linear regression model with satisfaction as the dependent variable and usage intensity as the independent variable to identify any communities that emerge as significant outliers beyond the 95% prediction interval. Analysis of regression residuals further corroborates the practice–perception decoupling phenomenon.

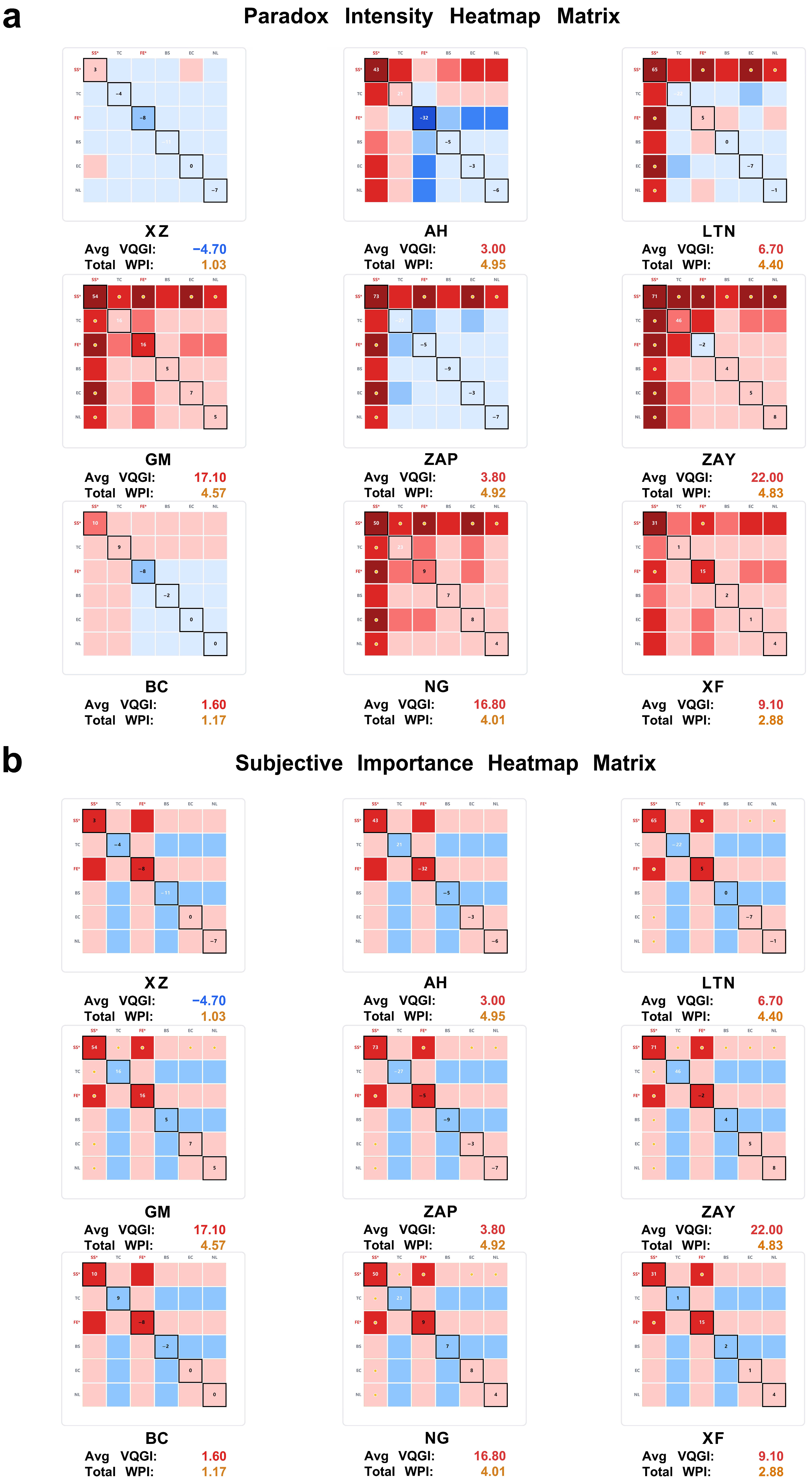

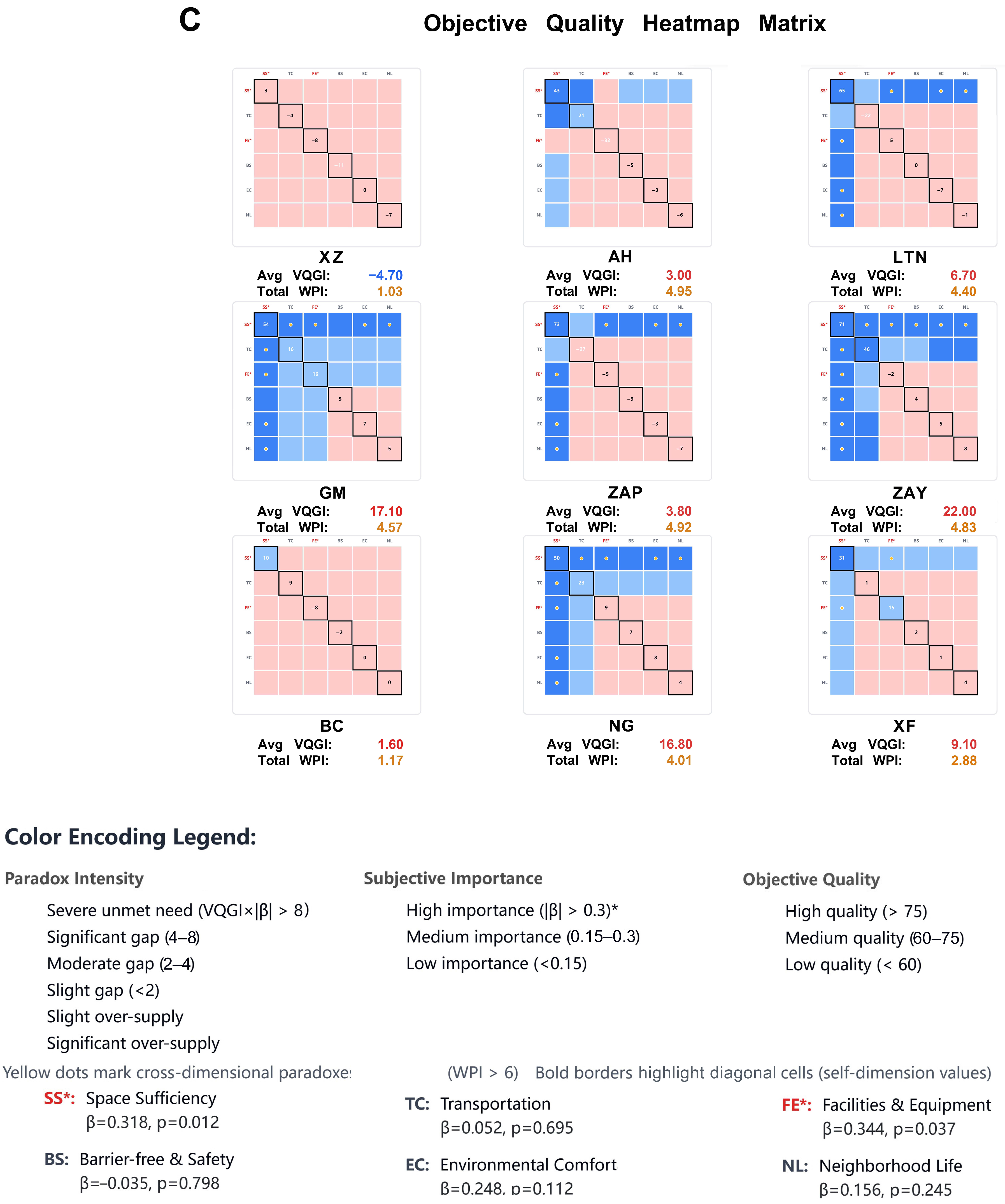

- Value Misalignment Paradox (Spatial Supply vs. Subjective Perception): This pathway reveals contradictions between objective environmental inputs and subjective preferences. The analysis proceeds in two steps. First, a multiple linear regression identifies the relative importance of the six environmental dimensions on overall satisfaction; the standardized regression coefficients indicate each dimension’s weight in influencing overall satisfaction. Second, we calculate the subjective–objective gap for each dimension in each community. We define a Value–Quality Gap Index (VQGI as the average satisfaction score for a given dimension minus the objective supply score for that same dimension. We then compute a Weighted Paradox Intensity (WPI, which considers both the magnitude of each dimension’s gap and its weight (importance) in shaping overall satisfaction. The WPI thus measures the severity of “value misalignment” in each community, aggregating the mismatches across all dimensions.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Disparities Across Communities

3.2. Paradox I: Supply–Practice Mismatch

3.3. Paradox II: Supply–Perception Mismatch

3.4. Paradox III: Practice–Perception Decoupling

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnostic Attribution

4.2. Typology-Based Prescriptions

- Spatially dormant communities (e.g., Longtan North and Zuo’an Puyuan) have abundant space and facilities that remain underutilized. The primary remedy in such cases is to unlock circulation and activate time slots. In terms of space, this involves enhancing the continuity and visibility of pathways (connecting internal courtyards to main routes) and adding inviting nodes such as corner rest spots and continuous seating, thereby creating a “route–node–plane” network that encourages congregation. This approach mirrors successful “micro-regeneration” strategies in aging Japanese suburbs, where underutilized pockets of land or vacant properties (akiya) are repurposed into small-scale community nodes to re-establish severed social connections within mature neighborhoods [121]. In terms of time, key activities should be anchored around peak periods like morning exercise and evening gatherings. Publicizing daily activity schedules and guidelines—supported by light-touch management from community organizers—can help ensure regular programming and usage. These measures turn nominal supply into truly accessible and engaging space by leveraging small-scale interventions to foster social interaction.

- Space-constrained communities (e.g., Anhua Building and New Garden) suffer from chronic overcrowding and lack of expansion room. Here the focus should be on peak-hour dispersion and flexible capacity. During periods of high use, activities like dance sessions and exercise should be separated into distinct zones (using movable partitions or scheduling) to avoid mutual interference. The necessity of strict temporal management and spatial flexibility resonates with strategies employed in ultra-high-density contexts like Hong Kong. There, extreme spatial scarcity in older districts compels a reliance on rigid time-sharing of limited public spaces and the utilization of multi-functional podium levels to accommodate conflicting age-group activities throughout the day [122]. Supplementary seating and portable benches should be provided in dispersed locations, along with improved lighting and safety measures to support extended evening use. Such steps can relieve pressure on any single spot and better distribute activity loads over space and time.

- Moderately imbalanced communities (e.g., Banchang, Xingfu, Guangming) exhibit mixed issues of minor oversupply or undersupply. A precision calibration approach is recommended. For instance, Banchang and Xingfu would benefit from targeted additions such as more exercise stations and shaded seating areas in underutilized corners, while Guangming should prioritize completing its network of walking paths and installing a few additional fitness facilities to reduce single-point crowding and improve spatial connectivity.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rogers, W.A.; Ramadhani, W.A.; Harris, M.T. Defining aging in place: The intersectionality of space, person, and time. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, igaa036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komp-Leukkunen, K.; Sarasma, J. Social sustainability in aging populations: A systematic literature review. Gerontol. 2024, 64, gnad097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigonnesse, C.; Chaudhury, H. The landscape of “aging in place” in gerontology literature: Emergence, theoretical perspectives, and influencing factors. J. Aging Environ. 2020, 34, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Mazumdar, S.; Vasconcelos, A.C. Understanding the relationship between urban public space and social cohesion: A systematic review. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2024, 7, 155–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the aging process. In The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; Eisdorfer, C., Lawton, M.P., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.W.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F. Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontol. 2012, 52, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynoos, J.; Nishita, C.; Cicero, C.; Caraviello, R. Aging in place, housing, and the law. Elder Law J. 2008, 16, 77–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Ageing in place in the United Kingdom. Ageing Int. 2008, 32, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, E.A. Using ecological frameworks to advance a field of research, practice, and policy on aging-in-place initiatives. Gerontol. 2012, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Miao, X.; Geng, W.; Li, Z.; Li, L. Comprehensive renovation and optimization design of balconies in old residential buildings in Beijing: A study. Energy Build. 2023, 295, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, A.; Semprini, G.; Cattani, E.; Righi, A.; Tinti, F. Deep renovation in existing residential buildings through façade additions: A case study in a typical residential building of the 70s. Energy Build. 2018, 166, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, C.H.; Park, S.H. Changes in renovation policies in the era of sustainability. Energy Build. 2012, 47, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, S.; Ji, W.; Zhang, Q.; Eftekhari, M.; Shen, Y.; Yang, L.; Han, X. Issues and challenges of implementing comprehensive renovation at aged communities: A case study of residents’ survey. Energy Build. 2021, 249, 111231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabrooks, P.A.; Lee, R.E.; Gyurcsik, N.C. Resources for physical activity participation: Does availability and accessibility differ by neighborhood socioeconomic status? Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 25, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Witten, K.; Bartie, P. Neighbourhoods and health: A GIS approach to measuring community resource accessibility. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, A.J.H.; Buckingham, W.R. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible—The Neighborhood Atlas. New Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2456–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownson, R.C.; Hoehner, C.M.; Day, K.; Forsyth, A.; Sallis, J.F. Measuring the built environment for physical activity: State of the science. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S99–S123.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, J.D. Street fairs: Social space, social performance. Theatre J. 1996, 48, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaladdini, S.; Oktay, D. Urban public spaces and vitality: A socio-spatial analysis in the streets of Cypriot towns. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, L. Mobile social networks and urban public space. New Media Soc. 2010, 12, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; Lart, R.; Bostock, L.; Coomber, C. Factors that promote and hinder joint and integrated working between health and social care services: A review of research literature. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichsenring, K. Developing integrated health and social care services for older persons in Europe. Int. J. Integr. Care 2004, 4, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Jia, F. Toward a theory of supply chain fields—Understanding the institutional process of supply chain localization. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 58–59, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Malmberg, A. Competing structural and institutional influences on the geography of production in Europe. Environ. Plan. A 1992, 24, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, G. Beyond soft institutionalism: Accumulation, regulation, and their geographical fixes. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Contemporary public space, part two: Classification. J. Urban Des. 2010, 15, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V. Evaluating public space. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, R.; Kearns, A. Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2125–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henwood, B.F.; Katz, M.L.; Gilmer, T.P. Aging in place within permanent supportive housing. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, J.C., III; Greenberg, S.M.; Anderson, C.S.; Becker, K.; Bendok, B.R.; Cushman, M.; Fung, G.L.; Goldstein, J.N.; Macdonald, R.L.; Mitchell, P.H.; et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015, 46, 2032–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartelli, M.; Baiocchi, G.L.; Di Saverio, S.; Ferrara, F.; Labricciosa, F.M.; Ansaloni, L.; Coccolini, F.; Vijayan, D.; Abbas, A.; Abongwa, H.K.; et al. Prospective observational study on acute appendicitis worldwide (POSAW). World J. Emerg. Surg. 2018, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.L.; Kuo, Y.C.; Ho, Y.S.; Huang, C.C. Triple-negative breast cancer: Current understanding and future therapeutic breakthrough targeting cancer stemness. Cancers 2019, 11, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paydar, M.; Kamani-Fard, A.; Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R. Perceived security of women in relation to their path choice toward sustainable neighborhood in Santiago, Chile. Cities 2017, 60, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanleerberghe, P.; De Witte, N.; Claes, C.; Schalock, R.L.; Verté, D. The quality of life of older people aging in place: A literature review. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Choi, J.; No, W.; Kim, J. Accessibility of welfare facilities for elderly people in Daejeon, South Korea considering public transportation accessibility. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 12, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Butcher, D.; Ashton, D. Innovative models of collaboration to serve children, youths, families, and communities. Child. Sch. 2004, 26, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvale, G.; Moll, S.; Miatello, A.; Robert, G.; Larkin, M.; Palmer, V.J.; Powell, A.; Gable, C.; Girling, M. Codesigning health and other public services with vulnerable and disadvantaged populations: Insights from an international collaboration. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorley, S.; Witthoft, S. Make Space: How to Set the Stage for Creative Collaboration; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bardach, E. Getting Agencies to Work Together: The Practice and Theory of Managerial Craftsmanship; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C.; Chanen, A.; Hodges, C.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Killackey, E. Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, N.D.; Roehrich, J.K.; George, G. Social value creation and relational coordination in public–private collaborations. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 906–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florinsky, I.V. Combined analysis of digital terrain models and remotely sensed data in landscape investigations. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 1998, 22, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatomiwa, L.; Mekhilef, S.; Huda, A.S.N.; Ohunakin, O.S. Economic evaluation of hybrid energy systems for rural electrification in six geo-political zones of Nigeria. Renew. Energy 2015, 83, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; Giordano, V.; Kaufman, S.; Russell, P.; Tiesdell, S. Public Space Design and Social Cohesion: An International Comparison; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Ehrenfeucht, R. Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation over Public Space; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M. On the Plaza: The Politics of Public Space and Culture; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Szanton, S.L.; Leff, B.; Wolff, J.L.; Roberts, L.; Gitlin, L.N. Home-based care program reduces disability and promotes aging in place. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujnowska-Fedak, M.M.; Grata-Borkowska, U. Use of telemedicine-based care for the aging and elderly: Promises and pitfalls. Smart Homecare Technol. TeleHealth 2015, 3, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ng, M.K.; Chao, T.Y.S.; Ong, A.; Chow, C.K. The impact of place attachment on well-being for older people in high-density urban environment: A qualitative study. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2024, 36, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilleard, C.; Hyde, M.; Higgs, P. The impact of age, place, aging in place, and attachment to place on the well-being of the over 50s in England. Res. Aging 2007, 29, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, S.; Prentice, C.; Hsiao, A. The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M.; Altman, I. Place attachment: A conceptual inquiry. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kleine, S.S.; Baker, S.M. An integrative review of material possession attachment. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2004, 1, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch, U.; Robertson, K.; Aitken, R. Experience, emotion, and eudaimonia: A consideration of tourist experiences and well-being. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E.S. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontol. 2012, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermalin, A.I. The Well-Being of the Elderly in Asia: A Four-Country Comparative Study; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, W.A.; Okun, M.A.; Benin, M. Structure of subjective well-being among the elderly. Psychol. Aging 1986, 1, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garatachea, N.; Molinero, O.; Martínez-García, R.; Jiménez-Jiménez, R.; González-Gallego, J.; Márquez, S. Feelings of well being in elderly people: Relationship to physical activity and physical function. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 48, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Pan, Y. The Construction of Resilience in Aging-Friendly Cities Driven by Land Adaptive Management: An Empirical Analysis of 269 Chinese Cities Based on the Theory of Social Ecosystems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Reflections on place and place-making in the cities of China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Gu, Y.; Yang, J.; Shao, M. Multidimensional evaluation of the process of constructing age-friendly communities among different aged community residents in Beijing, China: Cross-sectional questionnaire study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2025, 11, e66248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiser, W.; Vischer, J. (Eds.) Assessing Building Performance; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, H.F.; Iranmanesh, R.; Iturralde, D.; Spaide, R.F. Outcomes of 77 consecutive cases of 23-gauge transconjunctival vitrectomy surgery for posterior segment disease. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 1197–1200.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formica, S.; Uysal, M. Destination attractiveness based on supply and demand evaluations: An analytical framework. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, H.W.; Gebauer, H. Exploring the alignment between service strategy and service innovation. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edler, J.; Georghiou, L.; Blind, K.; Uyarra, E. Evaluating the demand side: New challenges for evaluation. Res. Eval. 2012, 21, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, J.C.E.; Cross, S.S. General and Systematic Pathology E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin, A. Dictionary of Environmental and Sustainable Development; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, D.N.; Feldman, M.; Carter, A.B.; Dighe, A.S.; Pfeifer, J.D.; Bry, L.; Almeida, J.S.; Saltz, J.; Braun, J.; Tomaszewski, J.E.; et al. Computational pathology: A path ahead. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, J. Theorizing community development. J. Community Dev. Soc. 2004, 34, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, W.; He, B.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y. Renovation priorities for old residential districts based on resident satisfaction: An application of asymmetric impact-performance analysis in Xi’an, China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Winter, J.C.F.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: A tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L.; Niemeier, D.A. Measuring accessibility: An exploration of issues and alternatives. Environ. Plan. A 1997, 29, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedikt, M.L. To take hold of space: Isovists and isovist fields. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1979, 6, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union; Joint Research Centre; OECD. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo, M.; Clericuzio, M.; Murino, T.; Sepe, C. An economic order quantity stochastic dynamic optimization model in a logistic 4.0 environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cao, G. Spatial-temporal coverage optimization in wireless sensor networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2011, 10, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, T.L.; Cohen, D.A.; Sehgal, A.; Williamson, S.; Golinelli, D. System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC): Reliability and feasibility measures. J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, S208–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roess, R.P.; Prassas, E.S. The Highway Capacity Manual: A Conceptual and Research History; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macbeth, G.; Razumiejczyk, E.; Ledesma, R.D. Cliff’s delta calculator: A non-parametric effect size program for two groups of observations. Univ. Psychol. 2011, 10, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.R. Likert scales: A history. In Proceedings of the Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing, Long Beach, CA, USA, 28 April–1 May 2005; Volume 12, pp. 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Murdock, C.; Rounds, J. Person–environment fit. In APA Handbook of Career Intervention, Volume 1: Foundations; Walsh, W.B., Brown, S.D., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerny, B.A.; Kaiser, H.F. A study of a measure of sampling adequacy for factor-analytic correlation matrices. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1977, 12, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A. Perceived service quality as a customer-based performance measure: An empirical examination of organizational barriers using an extended service quality model. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1991, 30, 335–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.X. It’s about time. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Poppe, C.H.; Anderson, J.D.; Davis, J.C.; Tickle, R.; McClenahan, C.W. Cross sections for the Li-7(p, n) Be-7 reaction between 4.2 and 26 MeV. Phys. Rev. C 1976, 14, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti, B.F.; Barrella, F.A.; Almeida, C.M.V.B. A combined tool for environmental scientists and decision makers: Ternary diagrams and emergy accounting. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyunt, M.S.Z.; Shuvo, F.K.; Eng, J.Y.; Yap, K.B.; Scherer, S.; Hee, L.M.; Chan, S.P.; Ng, T.P. Objective and subjective measures of neighborhood environment (NE): Relationships with transportation physical activity among older persons. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.L.; Leffert, N.; Scales, P.C.; Blyth, D.A. Beyond the “Village” rhetoric: Creating healthy communities for children and adolescents. Appl. Dev. Sci. 1998, 2, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Armstrong, B.; Jaakkola, J.J.K.; Tong, S.; Pan, X. Extremely cold and hot temperatures increase the risk of ischaemic heart disease mortality: Epidemiological evidence from China. Heart 2013, 99, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markovic, R.; Frisch, J.; van Treeck, C. Learning short-term past as predictor of window opening-related human behavior in commercial buildings. Energy Build. 2019, 185, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, O.S.; Kumar, S. Analytic hierarchy process: An overview of applications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 169, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Poza, A.; Sousa-Poza, A.A. Taking another look at the gender/job-satisfaction paradox. Kyklos 2000, 53, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschbach, P. The “well-being paradox” in quality-of-life research. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2002, 52, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, O. Development of life satisfaction in old age: Another view on the “paradox”. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 75, 241–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Pilon, P.; Cavadias, G. Power of the Mann–Kendall and Spearman’s rho tests for detecting monotonic trends in hydrological series. J. Hydrol. 2002, 259, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, K.; Harun, N.Z.; Mansor, M. Spatial characteristics of urban square and sociability: A review of the City Square, Melbourne. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 153, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D.; Balakrishnan, R. Interactive public ambient displays: Transitioning from implicit to explicit, public to personal, interaction with multiple users. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 24–27 October 2004; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P. Street performance and the city: Public space, sociality, and intervening in the everyday. Space Cult. 2011, 14, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, C.H.; Arentze, T.; Hofman, F.; Timmermans, H. Activity pattern similarity: A multidimensional sequence alignment method. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2002, 36, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glei, D.A.; Landau, D.A.; Goldman, N.; Chuang, Y.L.; Rodríguez, G.; Weinstein, M. Participating in social activities helps preserve cognitive function: An analysis of a longitudinal, population-based study of the elderly. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaine, S.J.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Batley, G.E.; Fernandes, T.F.; Handy, R.D.; Lyon, D.Y.; Mahendra, S.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Lead, J.R. Nanomaterials in the environment: Behavior, fate, bioavailability, and effects. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 1825–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K. Changing attitudes towards persons with disabilities in Asia. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2001, 21, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.R.; Siu, O.; Yeh, A.G.O.; Cheng, K.H. The impacts of dwelling conditions on older persons’ psychological well-being in Hong Kong: The mediating role of residential satisfaction. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 2785–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, E. Community Vulnerability and Capacity in Post-Disaster Recovery: The Cases of Mano and Mikura Neighbourhoods in the Wake of the 1995 Kobe Earthquake. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleimen-Malkoun, R.; Temprado, J.J.; Hong, S.L. Aging induced loss of complexity and dedifferentiation: Consequences for coordination dynamics within and between brain, muscular and behavioral levels. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botwinick, J. Aging and Behavior: A Comprehensive Integration of Research Findings, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ory, M.G.; Cox, D.M. Forging ahead: Linking health and behavior to improve quality of life in older people. Soc. Indic. Res. 1994, 33, 89–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A.; Funck, C. Living cities in Japan. In Living Cities in Japan; Sorensen, A., Funck, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 19–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Micro-regeneration in Shanghai and the public-isation of space. Habitat Int. 2023, 132, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruefenacht, L.; Acero, J.A. Strategies for Cooling Singapore: A Catalogue of 80+ Measures to Mitigate Urban Heat Island and Improve Outdoor Thermal Comfort; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiya, N.; Noguchi, H.; Nishi, A.; Reich, M.R.; Ikegami, N.; Hashimoto, H.; Shibuya, K.; Kawachi, I.; Campbell, J.C. Population ageing and wellbeing: Lessons from Japan’s long-term care insurance policy. Lancet 2011, 378, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L. State-led metropolitan governance in China: Making integrated city regions. Cities 2014, 41, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, T. Implementation process and challenges for the community-based integrated care system in Japan. Int. J. Integr. Care 2014, 14, e002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberg, J.; Nathan, A.; Barnett, A.; Barnett, D.W.; Cerin, E.; The Council on Environment and Physical Activity (CEPA)-Older Adults Working Group. Relationships between neighbourhood physical environmental attributes and older adults’ leisure-time physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1635–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damodaran, L. User involvement in the systems design process—A practical guide for users. Behav. Inf. Technol. 1996, 15, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, I.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creating in practice: Results and challenges. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Technology Management Conference (ICE), Leiden, The Netherlands, 22–24 June 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.R. Personal privacy in the computer age: The challenge of a new technology in an information-oriented society. Mich. Law Rev. 1968, 67, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Indicators | Formula & Calculation | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. THREE BASELINES: Tri-dimensional Data Streams | |||

| A1. Spatial Supply (Built Environment Audit) | Iloca [76,77] | ≥0.75 (High) 0.50–0.75 (Medium) | |

| Iopen [78] | ≥0.6 (Open) 0.4–0.6 (Medium) | ||

| zk [79] | Q1/Q2/Q3 quartiles Missing items flagged | ||

| Balance [80] | CV ≤ 0.3 (Balanced) CV > 0.3(Imbalanced) | ||

| AP [81] | Sample quartiles | ||

| SQI [82] | 0–60 (Weak) 60–80 (Medium) >80 (High) | ||

| A2. Spatial Practice (Systematic Observation) | Temporal Coverage [83] | 1.0 (Full coverage) | |

| Intensity [84] | ≥Q3 (High) Q2–Q3 (Medium) | ||

| PHR [85] | >2.5(Significant peak) 1.5–2.5 (Moderate) | ||

| TCI [86] | 38–46 (Medium) >46 (Concentrated) | ||

| MVR [87] | ≥50% (High return) 25–50% (Medium) | ||

| A3. Spatial Perception (Survey & Interview) | [88,89] | ≥4 (High) 3–4 (Medium) | |

| CS/PI [90] | ≥80 (High) 60–80 (Medium) | ||

| Scale Quality [91] | α ≥ 0.70 KMO ≥ 0.60 Bartlett p < 0.05 | ||

| B. THREE PARADOXES: Diagnostic Pathways | |||

| B1. Supply↔Practice (SPP) | FFI [92] | >0.30 (Severe failure) 0.10–0.30 (Moderate) ±0.10 (Matched) <−0.10 (Overuse) | |

| ELR [93] | >60% (High loss) 30–60% (Medium) | ||

| ρ [94] | ρ→1 (Consistent) ρ→0 (Independent) ρ<0 (Paradox) | ||

| B2. Supply↔Perception (SPeP) | VQGI [94] | >+30 (Severe gap) +10 to +30 (Medium) −10 to +10 (Matched) <−10 (Oversupply) | |

| WPI [95] | >6.0 (Critical) 3.0–6.0 (Significant) 1.5–3.0 (Moderate) ≤1.5 (Acceptable) | ||

| B3. Practice↔Perception (PPP) | r [96] | r < 0.3 (Negative) |r| < 0.3 (Weak) r > 0.5 (Strong) | |

| e* [97] | |e*| > 2 (Outlier) 95% CI band for deviation | ||

| B4. Integrated (Ternary Analysis) | s, pr, pe [98] | Center = balanced Vertices = extreme | |

| Pairwise Paradox Index [99] | 0(Ideal)1(Extreme) | ||

| TPI [100] | Q1/Q2/Q3 based on sample distribution | ||

| Community | Basic Infrastructure | Spatial Configuration | Facility Provision (%) | Composite Indices | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites a | Area (m2) | Iloca b | Iopen c | Seating | Toilets | Exercise | AP d | SQI e | |

| XZ | 9 | 15,180 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 78 | 22 | 89 | 4.30 | 77.00 |

| AH | 4 | 1150 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0.30 | 76.90 |

| LTN | 12 | 96,150 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 67 | 8 | 83 | 28.50 | 73.90 |

| GM | 5 | 1420 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 50 | 0 | 100 | 0.10 | 62.00 |

| ZAP | 8 | 44,280 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 75 | 13 | 88 | 100.00 | 58.30 |

| ZAY | 4 | 12,020 | 0.41 | 0.97 | 75 | 0 | 75 | 1.40 | 51.40 |

| BC | 5 | 3300 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 80 | 0 | 80 | 1.00 | 49.60 |

| NG | 5 | 1100 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 60 | 0 | 100 | 0.30 | 46.70 |

| XF | 7 | 6830 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 57 | 0 | 86 | 1.90 | 43.30 |

| Community | Usage Volume | Temporal Patterns | Activity Organization (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users a | Intensity b | MVR c | Peak d | PHR e | TCI f | Individual | Group | Collective | |

| XZ | 520 | 3.4 | 42 | Evening | 2.8 | 48 | 22 | 45 | 33 |

| AH | 180 | 15.7 | 38 | Morning | 3.2 | 52 | 15 | 50 | 35 |

| LTN | 850 | 1.9 | 48 | Evening | 2.2 | 45 | 28 | 42 | 30 |

| GM | 145 | 10.2 | 40 | Evening | 2.9 | 50 | 20 | 48 | 32 |

| ZAP | 680 | 1.5 | 52 | Evening | 2.0 | 42 | 35 | 40 | 25 |

| ZAY | 220 | 1.8 | 55 | Noon | 1.8 | 40 | 38 | 38 | 24 |

| BC | 165 | 5.0 | 46 | Evening | 2.5 | 46 | 30 | 42 | 28 |

| NG | 125 | 11.4 | 39 | Morning | 3.0 | 51 | 18 | 47 | 35 |

| XF | 285 | 4.2 | 50 | Evening | 2.3 | 44 | 32 | 40 | 28 |

| Evaluation Dimension | Community Sample | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH | BC | GM | LTN | XZ | NG | XF | ZAP | ZAY | Overall | ||

| (n = 24) | (n = 30) | (n = 60) | (n = 42) | (n = 36) | (n = 18) | (n = 30) | (n = 66) | (n = 54) | |||

| Six-Dimension Satisfaction (Mean ± SD), Variability (CV), and Performance Index (PI) by Community | |||||||||||

| Space Sufficiency | M ± SD | 3.75 ± 0.50 | 3.60 ± 0.55 | 3.80 ± 0.63 | 3.43 ± 0.53 | 3.83 ± 0.41 | 4.00 ± 0.00 | 3.80 ± 0.45 | 3.73 ± 0.47 | 3.67 ± 0.50 | 3.71 ± 0.49 |

| CV (%) | 13.33 | 15.28 | 16.58 | 15.45 | 10.7 | 0 | 11.84 | 12.6 | 13.62 | 13.21 | |

| PI | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.63 | |

| Transportation | M ± SD | 4.00 ± 0.82 | 3.80 ± 0.84 | 3.90 ± 0.57 | 3.71 ± 0.76 | 3.67 ± 0.82 | 4.33 ± 0.58 | 4.00 ± 0.71 | 3.82 ± 0.60 | 3.78 ± 0.67 | 3.85 ± 0.69 |

| CV (%) | 20.5 | 22.11 | 14.62 | 20.49 | 22.34 | 13.4 | 17.75 | 15.71 | 17.72 | 17.92 | |

| PI | 0.6 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.6 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.58 | |

| Facilities & Equipment | M ± SD | 3.50 ± 0.58 | 3.40 ± 0.55 | 3.60 ± 0.52 | 3.29 ± 0.49 | 3.50 ± 0.55 | 3.67 ± 0.58 | 3.60 ± 0.55 | 3.45 ± 0.52 | 3.44 ± 0.53 | 3.48 ± 0.53 |

| CV (%) | 16.57 | 16.18 | 14.44 | 14.89 | 15.71 | 15.81 | 15.28 | 15.07 | 15.41 | 15.23 | |

| PI | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.7 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.67 | |

| Accessibility | M ± SD | 3.63 ± 0.48 | 3.50 ± 0.50 | 3.75 ± 0.43 | 3.36 ± 0.45 | 3.58 ± 0.49 | 3.83 ± 0.29 | 3.70 ± 0.42 | 3.59 ± 0.47 | 3.56 ± 0.46 | 3.60 ± 0.45 |

| CV (%) | 13.22 | 14.29 | 11.47 | 13.39 | 13.69 | 7.57 | 11.35 | 13.09 | 12.92 | 12.5 | |

| PI | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.76 | |

| Environmental Comfort | M ± SD | 3.75 ± 0.50 | 3.60 ± 0.55 | 3.80 ± 0.42 | 3.43 ± 0.53 | 3.67 ± 0.52 | 4.00 ± 0.00 | 3.80 ± 0.45 | 3.64 ± 0.50 | 3.67 ± 0.50 | 3.68 ± 0.48 |

| CV (%) | 13.33 | 15.28 | 11.05 | 15.45 | 14.17 | 0 | 11.84 | 13.74 | 13.62 | 13.04 | |

| PI | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.7 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.71 | |

| Neighborhood Life | M ± SD | 3.88 ± 0.43 | 3.70 ± 0.42 | 3.85 ± 0.34 | 3.50 ± 0.41 | 3.75 ± 0.39 | 4.17 ± 0.29 | 3.90 ± 0.36 | 3.68 ± 0.40 | 3.72 ± 0.39 | 3.76 ± 0.39 |

| CV (%) | 11.08 | 11.35 | 8.83 | 11.71 | 10.4 | 6.96 | 9.23 | 10.87 | 10.48 | 10.37 | |

| PI | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.79 | |

| Overall Satisfaction by Community: Perception Index (PI) and Composite Score (CS) | |||||||||||

| evaluate | PI | 4.2 | 4.04 | 4.26 | 3.88 | 4.11 | 4.49 | 4.27 | 4.09 | 4.08 | 4.14 |

| result | CS | 4.2 | 4.04 | 4.26 | 3.88 | 4.11 | 4.49 | 4.27 | 4.09 | 4.08 | 4.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hui, L.; Zhang, B.; Luo, C. Unveiling Paradoxes: A Multi-Source Data-Driven Spatial Pathology Diagnosis of Outdoor Activity Spaces for Aging in Place in Beijing’s “Frozen Fabric” Communities. Land 2026, 15, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010020

Hui L, Zhang B, Luo C. Unveiling Paradoxes: A Multi-Source Data-Driven Spatial Pathology Diagnosis of Outdoor Activity Spaces for Aging in Place in Beijing’s “Frozen Fabric” Communities. Land. 2026; 15(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleHui, Linyuan, Bo Zhang, and Chuanwen Luo. 2026. "Unveiling Paradoxes: A Multi-Source Data-Driven Spatial Pathology Diagnosis of Outdoor Activity Spaces for Aging in Place in Beijing’s “Frozen Fabric” Communities" Land 15, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010020

APA StyleHui, L., Zhang, B., & Luo, C. (2026). Unveiling Paradoxes: A Multi-Source Data-Driven Spatial Pathology Diagnosis of Outdoor Activity Spaces for Aging in Place in Beijing’s “Frozen Fabric” Communities. Land, 15(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010020