Newcomers in Remote Rural Areas and Their Impact on the Local Community—The Case of Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction—The Theoretical Issues

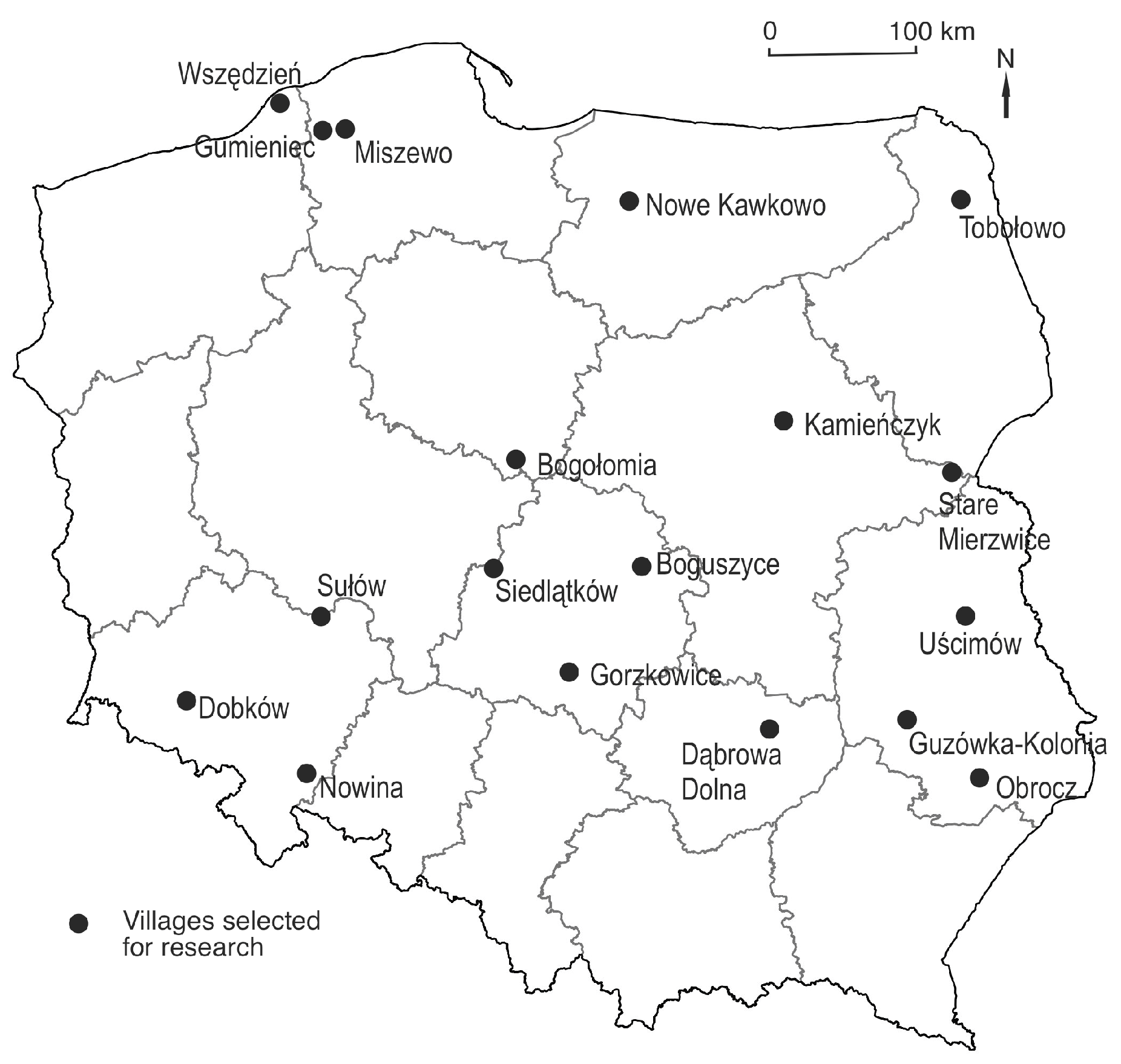

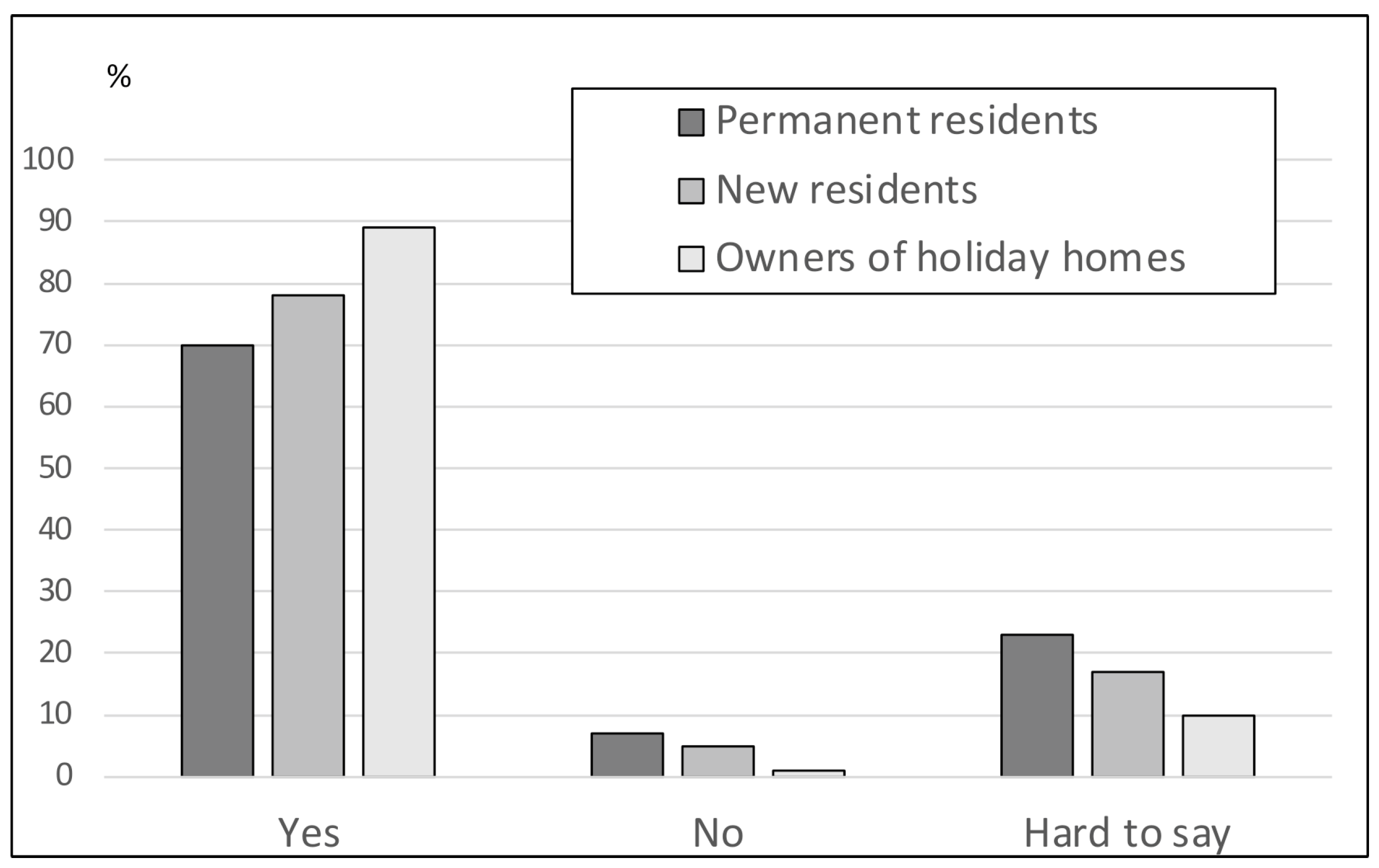

2. Study Area and Methodology

3. Analysis of Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Newcomers and Locations of Their Inflow—Opinions of Permanent Residents

- Persons looking for calm, peace, a better quality of life, and contact with nature; they are largely independent professionals or freelancers (artists, computer specialists, architects, lawyers, scientists, etc.), they mainly originate from large cities, and their professional life remains linked with the city;

- Entrepreneurs and “amateurs” who move to the countryside with the intention of conducting business (agro-tourism, other tourism-related services, handcrafts, food production, animal husbandry, and so on), and they are persons with business experience who try to make use of the countryside’s potential;

- Retired persons and representatives of free trades who transform their existing summer houses into whole-year residences, seeking a calm and cheaper life that is closer to nature;

- Persons returning “back to the roots”, i.e., those who had left the countryside before for the city or went abroad and who return after a longer time to the locality of their birth; this group also includes retired persons and those who undertake business activities.

A large group of people from Warsaw came to Kamieńczyk, attracted by the rivers Bug and Liwiec, forests, nice natural environment, who have built here and in the neighborhood, summer houses…(an inhabitant of the village of Kamieńczyk);

Our region is attractive as regards tourism, landscape, and so for these reasons, partly, it is being chosen by the urbanites… Since its tourist attractiveness increases, hence a part of these persons definitely sees their life as associated with small tourist business …(clerk in the municipality office of Dobków).

The newcomers are single persons, who came from the city and who like it in the countryside. They are professionally active, some work on their own, other commute to the city. They bought here old, “formerly German” houses…, which they repaired—far from the hustle, in peace and calm. … They are very keen regarding the esthetics of the farmyard(marshal of the village of Gumieniec2).

… over the last few years some new persons arrived and they come, decidedly, from the large cities. They are such people, who often have never lived in the countryside. Simply, they try to find here a new manner of living… They decidedly represent independent professions…(local social female leader in the village of Nowina).

… Recently, more and more people turn their summer houses into permanent residences. Mainly the retirees. They leave their apartments in the city to their children, and move into here for good. But young people do also work from here through teleworking.(local social leader from the village of Mierzwice).

… Most often these are the persons, who still partly live in the big city, but they bought an estate and start to find a solution that would allow them to move into the countryside. I can give such an example of a family, who bought two years ago an old house in Dobków, they are repairing this house all the time, do some activities already on place, in the village, but cannot yet make their living uniquely from these activities, and so they still reside in the city(owner of an agro-tourist farm in the village of Dobków).

… Those, who settled here permanently, are the persons from large cities, Włocławek, Lodz, and those, who come here only for some period, are also most frequently from the city … Those who settled here for good only reside here, and their professional life is linked with the city, they do not get involved, rather, in the village life, they came, because they liked the area.(owner of a shop in the village of Bogołomia).

… In the neighborhood of my estate second homes have been built, belonging to the newcomers, whom I do not know and whom I am not even capable of recognizing. Clearly, the newcomers come mostly from Warsaw and from the localities near Warsaw. The newcomers are very much demanding, which is not to the liking of the inhabitants of Kamieńczyk. They are mostly interested in their own affairs and do not care for the needs of other inhabitants.(marshal of the village of Kamieńczyk).

… All these persons, who came here and settled down, are educated and cultivated people, with a lot of knowledge, very kind, helpful, and, at the same time, modest, not considering themselves superior to the others. Likewise, they do not show jealousy nor cynical smartness, so often encountered in the countryside. It is owing to these people that the village lives at all. On the other hand, they sometimes present strange behavior (like, e.g., barefoot walking)—but there is nothing wrong with this. They do not complain about anything, including farming odors, cows, etc.(marshal’s wife in the village of Nowe Kawkowo).

3.2. Characterization of Relations Between Newcomers from the City and Permanent Residents

3.2.1. Intensity and Location of Contact Between Newcomers from the City and Permanent Residents

… The shop is the point of information exchange. People talk a lot and exchange current information… The shop is the place, where those, who do not live here daily can get information on local specialists, from whom one can buy something, who provides what kind of service, whether an establishment is working(female shop owner in the village of Mierzwice)

… My shop has become such a point of tourist information. The announcements are hanging here on the organized excursions, boat rides. In view of my being a council member for already 15 years, local people, interested in business matters come to me with questions concerning, e.g., photovoltaics, waste removal, internet installation, and so on. I am a kind of contact point and an intermediary between the inhabitants and the municipal office(shop owner in the village of Tobołowo)

3.2.2. Themes of Encounters

… they most frequently talk of private matters, some leisure time, lifestyle, someone boasts a recent purchase and where was it done. It also happens that people talk of matters, related to construction(shop owner in the village of Bogołomia).

The most frequent subject of conversations is politics, high prices, but also jokes, especially during the integrating meetings with the newcomers at a fire with some vodka or moonshine (the latter highly appreciated by the newcomers). Women exchange their cuisine experiences, speak about fashion, about life of celebrities. These conversations have a private character and do rather not exert any influence on the social life and village development, at least not directly, since contacts with so different people certainly indirectly and in a tacit manner leave an impact on the opinions.(inhabitant of the village of Tobołowo).

We talk most often of private life, as nothing much happens in our village. We exchange news on what is going on here, the things that concern us directly (…) I am an advocate and neighbors sometimes ask me about various things, associated with solving of their problems(newcomer from the city in the village of Bogołomia).

3.2.3. Directions of Transfer of Knowledge and Experience

… It is mainly a unidirectional knowledge, from me to them, since it is them, who try to learn as much as possible on cultivation. We talk sometimes when the newcomers are doing shopping. They learn how to take care of hens, cultivate ecological vegetables, and so on. I do mainly answer the questions, and do not ask about anything…(farmer from the village of Boguszyce)

… The flow of information is unidirectional. The newcomers are interested in where one can buy various products, like eggs, poultry, vegetables, potatoes, milk. Sometimes they look for persons, who, for instance, have construction equipment or provide specialized services…(marshal of the village of Guzówka).

4. Influence of Newcomers on Rural Social Life—A Discussion

… People from the outside… motivate the residents to joint activities. It is very frequent that this person from the outside overcomes the passive attitude and undertakes formation of a group, attempting to acquire some funds, in order to prepare something for the village. I think that these newcomers may bring a renewal of social activity, and also business activation(employee of the municipal office in the village of Dobków).

The village is generally very much united, consonant, active, tolerant, open. Persons, having come here from the city, changed the village. Without them, it would die out. There would be nothing here. Owing to these people the village lives at all. The village gained a lot, old traditions are being maintained, old houses are taken care of and repaired, along with other farm buildings. The village lives, something is going on here, there is activity, cooperation. All this is due to the newcomers.(marshal’s wife in the village of Nowe Kawkowo).

A part of inhabitants of the village get direct benefits—they sell their produce or rent rooms to tourists. Some organize boat excursions, and so they earn money in this way. Yet, there is a certain group of permanent residents of the village, who do not approve of the situation. The village becomes too crowded and too noisy for them. They are not satisfied with the increasing inflow of the “strangers” to the village.(council member from the village of Obrocz).

There are also conflicts, associated with the development and spatial organization of the village. The newcomers, but also a part of the locals, would like to defend the village against modernization. At the same time, there is a group of persons (local residents, but first of all a council member, who came from somewhere beyond Olsztyn [regional provincial capital]), who attempted to build, with EU money, a sidewalk of paving blocks by the church, along with a pedestrian street passage and a slowdown threshold for drivers, with appropriate road signs. The sidewalk was built, but the newcomers (and partly the locals) did not like it, because it was built of standard paving blocks, with no relation to the regional, Warmian style and tradition. An association, formed by the newcomers, acted against this project.(marshal’s wife in the village of Nowe Kawkowo).

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

| 1 | One of the questions in the questionnaire concerned the time period of living in the countryside. The analysis of the questionnaire-based results, regarding “permanent residents”, as only those persons were chosen, who had declared living since their birth in the countryside. |

| 2 | Located in the part of Poland which had belonged before WWII to Germany. |

References

- Adamiak, C.; Pitkanen, K.; Lehtonen, O. Seasonal residence and counterurbanization: The role of second homes in population redistribution in Finland. Geojournal 2023, 82, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. Heterolocal identities? Counter-urbanisation, second homes, and rural consumption in the era of mobilities. Popul. Space Place 2012, 18, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K.H. Out of place in the country: Travellers and the‘rural idyll’. Antipode 1996, 28, 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G. Alternative Trade or Market Fragmentation? Food Circuits and Social Movements; Quaderni Sismondi Working paper; Laboratorio di Studi Rurali Sismondi: Pisa, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halfacree, K. Back-to-the-land in the twenty-first century–making connections with rurality. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2007, 98, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J. Alternative lifestyle spaces. In Alternative Economic Spaces; Leyshon, A., Lee, R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2003; pp. 168–193. [Google Scholar]

- Trauger, A. Connecting social justice to sustainability: Discourse and practice in sustainable agriculture in Pennsylvania. In Alternative Food Geographies; Maye, D., Holloway, L., Kneafsey, M., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2007; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur, A. Back-to-the-house? Gender, domesticity and (dis)empowerment among back-to-the-land migrants in Northern Italy. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkartzios, M.; Scott, M. Residential mobilities and house building in rural Ireland: Evidence from three case studies. Sociol. Rural. 2009, 50, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. To revitalise counter-urbanisation research? Recognising an international and fuller picture. Popul. Space Place 2008, 14, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, P. Counterurbanisation, Demographic Change and Discourses of Rural Revival in Australia during COVID-19. Aust. Geogr. 2022, 53, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. The patterns and places of counterurbanisation: A ‘macro’ perspective from Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijker, R.; Haartsen, T.; Strijker, D. Migration to less-popular rural areas in the Netherlands: Exploring the motivations. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, M.; Newbold, K.B. Poverty catchments: Migration, residential mobility, and population turnover in impoverished rural Illinois communities. Rural Sociol. 2008, 73, 440–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitos, J.G.; Ruckriegle, H. The Problem of Amenity Migrants in North America and Europe. Urban Lawyer 2013, 45, 849–914. [Google Scholar]

- Rainer, G. Amenity/lifestyle migration to the Global South: Driving forces and socio-spatial implications in Latin America. Third World Q. 2019, 40, 1359–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M. Migration and the search for a better way of life: A critical exploration of lifestyle migration. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 57, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Sene-Harper, A.; Stocks, G. International amenity migration: Examining environmental behaviors and influences of amenity migrants and local residents in a rural community. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Making sense of counterurbanisation. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haartsen, T.; Stockdale, A. Selective belonging: How rural newcomer families with children become stayers. Popul. Sapce Place 2018, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Karsten, L. Counterurbanisation: Why settled families move out of the city again. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimon, M. Exploring Counterurbanisation in a Post-Socialist Context: Case of the Czech Republic. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 54, 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J.; Wesołowska, M. Disappearing villages in Poland-selected socioeconomic processes and spatial phenomena. Eur. Countrys. 2020, 12, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, R. Village for Sale! Access and Contention in Woodland Properties: Implications for Rural Futures in Northern Spain; International Institute of Social Studies: Hague, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Di Figlia, L. Places in memory. Abandoned villages in Italy. In Architecture, Archeology and Contemporary City Planning; Verdiani, G., Cornell, P., Eds.; Proceedings of the Workshop: Florence, Italy, 2014; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, P.; Šipoš, J.; Müllerová, J. Township boundaries and the colonization of the Moravian landscape. J. Hist. Geogr. 2017, 57, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michele, B.; Luisa, C.M.; Martina, L.C.; Simone, B. Migrants in the economy of european rural and mountain areas. A cross-national investigation of their economic integration. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 99, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Geng, B.; Wang, Y.; McCabe, S.; Liao, L.; Zeng, L.; Deng, B. Reverse entrepreneurship and integration in poor areas of China: Case studies of tourism entrepreneurship in Ganzi Tibetan Region of Sichuan. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, C.; Duan, J. Multi-dimensional superposition: Rural collaborative governance in liushe village, suzhou city. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chan, E.; Song, H. Social capital and entrepreneurial mobility in early-stage tourism development: A case from rural China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.; Stedman, R. Culture Clash and Second Home Ownership in the U.S., Northern Forest. Rural Sociol. 2013, 78, 318–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herslund, L. The rural creative class: Counterurbanisation and entrepreneurship in the Danish countryside. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.L.; Leung, M. Trans-knowledge? Geography, mobility, and knowledge in transnational education. In Mobilities of Knowledge; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 269–285. [Google Scholar]

- Dopitiva, M. Social engagement and rural newcomers. Soc. Stud. 2016, 13, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, I.; Simoes, O.; Cruz, C.; Teodoro, A. Understanding the impact of intentions in the adoption of local development practices by rural tourism hosts in Portugal. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 72, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Korsgaard, S. Resources and bridging: The role of spatial context in rural entrepreneurship. Enterpren. Reg. Dev 2018, 30, 224–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Zollet, S. Neo-endogenous revitalisation: Enhancing community resilience through art tourism and rural entrepreneurship. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Geng, B.; Wu, B.; Liao, L. Determinants of returnees’ entrepreneurship in rural marginal China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krannich, R.S.; Luloff, A.E.; Field, D.R. People, Places and Landscapes: Social Change in High Amenity Rural Areas; Springer: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.D.; Krannich, R.S. ‘Culture Clash’ Revisited: Newcomer and Long-Term Resident’s Attitudes Toward Land Use, Development, and Environmental Issues in Rural Communities in the Rocky Mountain West. Rural Sociol. 2000, 65, 396–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, E. Resurgent back-to-the-land and the cultivation of a renewed countryside. Sociol. Rural. 2022, 63, 544–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallent, N. The Social Value of Second Homes in Rural Communities. Hous. Theory Soc. 2014, 31, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J.; Mazur, M.; Kamińska, W. Socioeconomic Conditioning of the Development of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Global Spatial Differentiation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 21, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, N.; Plummer, P. Counterurbanisation in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic in new South Wales, 2016–2021. Habitat Int. 2024, 150, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Leonardo, M.; Rowe, F.; Fresolone-Caparros, A. Rural revival? The rise in internal migration to rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Who moves and where? J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfacree, K. Counterurbanisation in post-covid-19 times. Signifier of resurgent interest in rural space across the global North? J. Rural Stud. 2024, 110, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Clarke, N.; Hracs, B.J. Urban-rural mobilities: The case of China’s rural tourism makers. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, E.; Allen, S.; Haggett, C. Incomers’ leading “community-led” low carbon initiatives: A contradiction in terms? Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2018, 37, 946–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noack, A.; Federwisch, T. Social Innovation in Rural Regions: Urban Impulses and Cross-Border Constellations of Actors. Sociol. Rural. 2018, 59, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, J.F. Conflicts and Contestations: Rural Populations’ Perspectives on the Second Home Phenomenon. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J. Urban-Rural Knowledge Transfer-A Theoretical and Methodological Approach. In Information Technology and Systems; Rocha, A., Ferras, C., Hochstetter Diez, J., Diéguez Rebolledo, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 12, pp. 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.; George, G. Absorptive Capacity: A Review, Reconceptualization, and Extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartiainen, P. Counterurbanisation: A challenge for socio-theoretical geography. J. Rural Stud. 1989, 5, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, N.; Scotson, J.L. The Established and the Outsiders; Sage Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Maffesoli, M. Czas Plemion; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dailey, G.H.; Campbell, R.R. The Ozark-Ouachita Uplands: Growth and Consequences. In New Directions in Urban-Rural Migration: The Population Turnaround in Rural America; Brown, D.L., Wardwell, J.M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Huijbens, E.H. Sustaining a Village’s Social Fabric? Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 332–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertsson, L.; Marjavaara, R. The Seasonal Buzz: Knowledge Transfer in a Temporary Setting. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2015, 12, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietäväinen, A.T.; Rinne, J.; Paloniemi, R.; Tuulentie, S. Participation of second home owners and permanent residents in local decision making: The case of a rural village in Finland. Int. J. Geogr. 2016, 194, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, B.M.; Krannich, R.S. Bonded to whom? Social interactions in a high-amenity rural setting. Community Dev. 2013, 44, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M.; Winston, N. Social, Economic and Environmental Impacts of Second Homes in Ireland. In Planning Sustainable Communities: Diversities of Approaches and Implementation Challenges; Tsenkova, S., Ed.; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2009; pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki, A. Going Local? Linking and Integrating Second-Home Owners with the Community’s Economy: A Comparative Study Between Finnish and Polish Second-Home Owners; Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Subjects of Conversations | Permanent Residents (%) | Newcomers (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Spending leisure time | 37 | 49 |

| Diet, food | 11 | 19 |

| Production | 9 | 17 |

| Odd jobs, additional revenue | 8 | 6 |

| Events, festivities | 27 | 53 |

| Construction | 14 | 11 |

| Medication, health | 31 | 28 |

| Hobbies | 17 | 24 |

| Sale of products | 12 | 28 |

| Provision of services | 18 | 29 |

| Esthetics of the environment | 14 | 12 |

| Politics | 16 | 9 |

| Shopping | 16 | 32 |

| Plant cultivation | 26 | 32 |

| Animal husbandry | 14 | 13 |

| Neighborhood assistance | 30 | 48 |

| New devices | 6 | 3 |

| Social life of the village | 28 | 46 |

| Other responses | 3 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bański, J. Newcomers in Remote Rural Areas and Their Impact on the Local Community—The Case of Poland. Land 2025, 14, 1904. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091904

Bański J. Newcomers in Remote Rural Areas and Their Impact on the Local Community—The Case of Poland. Land. 2025; 14(9):1904. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091904

Chicago/Turabian StyleBański, Jerzy. 2025. "Newcomers in Remote Rural Areas and Their Impact on the Local Community—The Case of Poland" Land 14, no. 9: 1904. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091904

APA StyleBański, J. (2025). Newcomers in Remote Rural Areas and Their Impact on the Local Community—The Case of Poland. Land, 14(9), 1904. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091904