1. Introduction

A “new town” is defined as a town initiated and planned by the state or by experts on its behalf. The new town is intended to encompass a comprehensive array of activities, enabling much of daily life to take place within it [

1]. Nevertheless, it is born out of a schematic model, which is the focus of this article.

According to Forsyth & Peiser (2021) [

1], the discourse on models for new towns—globally, and in Europe in particular—peaked in the years following World War II and continued until the late 1970s. During this period, 67 countries developed at least one new town with a population of 30,000 in 2021 (a figure drawn from the Garden City model, see below). Most were industrial towns located behind the Iron Curtain—that is, towns built around a factory to house workers, develop peripheral regions, and build scientific capacity. Many were also designed to decentralize the population. Approximately 28% of the new towns were built in Western Europe [

1], primarily in countries that adopted a centralized and interventionist approach to territorial development: the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands [

2].

Theoretical models developed prior to the world wars predominated the planning of the new towns. Soviet planners developed towns based on the linear city model [

3]. The Western European models, which form the core of this article, were grounded in two principal theories: the Garden City and the Athens Charter. The Garden City was designed to provide a high quality of life based on a low-rise, green-rich village, combined with diverse services and employment opportunities, as befits a self-sustained town. This model endowed the new towns with zoning, restriction of the target population (in the case of the Garden City, this was specifically defined as 30,000 inhabitants) and, in particular, with low density and proximity to nature [

4]. The Athens Charter of CIAM [

5] contributed the principles of zoning, access to nature, and especially the free-standing building layout—the “open plan”—set on large, street-less plots, as if the buildings were placed in a park, as further developed in the model of the Radiant City [

6,

7].

The new towns constructed by states reflected the hegemony’s control over everyday life—both because state-appointed planners expressed the prevailing worldview of their time, and because the city itself served as the container of daily life. Meticulously planned from the ground up, the towns thus embodied the hegemonic conception of what constitutes a proper environment, a suitable home, and, above all, a desirable lifestyle [

8]. Accordingly, alongside the physical response to needs—such as the provision of housing and the redistribution of populations that had concentrated in metropolitan areas in an unplanned and uncontrolled manner—the new towns also reflected worldviews: the provision of proper and just housing conditions for all (light, air, landscape), inspired by socialist values [

9]; educating residents for modernization [

10]; and the encouragement of communal cohesion in expansive open spaces and public institutions. It was believed that detailed planning—of streets and housing units, employment and economic frameworks—would make it possible to anticipate and address all future physical and social needs of the town and its residents [

1].

However, planning is one thing, and reality another. A new town is planned in the present for a target population, and its construction unfolds over several decades. To ensure that the population continues to grow, and to prevent outmigration during the process—which may ultimately lead to the decline of the new town—it is crucial to maintain a high quality of life throughout the stages of construction. It appears that some of the new towns have failed to reach their target populations. In their early years, the new towns suffered from a lack of infrastructure and from being isolated from their surroundings [

11]. Moreover, the quality-of-life promise failed to materialize, certainly not while the town was still under construction [

12]. In addition, the aspiration that new neighborhoods would generate communal life remained largely on paper. It became clear that people tended to build community with those similar to themselves, rather than merely with those encouraged or coerced to be located in their physical proximity [

11]. Finally, the new towns deliberately lacked an urban experience and were marked by visual monotony [

13]. In other words, in many respects, they were not necessarily better than the old cities they sought to “reform”—quite the opposite.

By the 1980s, it became clear that the foundational idea of modernism—that human reason and intellect could fully control reality and plan the future in absolute terms—was no longer tenable. Regarding town planning specifically, the city’s inherently complex structure proved highly resistant to such control. In his monumental work, S, M, L, XL: Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rem Koolhaas argues that the role of “new urbanism” is no longer to pursue stable and absolute forms, but rather to enable processes that, at present, are entirely unpredictable. In other words, urban planning should serve merely as an enabling infrastructure [

14]. Consequently, there is no longer any point in developing fixed physical models for new towns. Reflecting this shift, the International New Town Association has, since the early 1990s, been renamed the International Urban Development Association [

11].

The values used to inform the new towns have also lost traction. The socialist value has given way to the glorification of individualism and to neoliberalism. The state now takes less responsibility for the welfare of young couples and families—once the primary target population of the new towns [

15]. The aspiration for communal resilience, which had been dominant in the post–World War II era and which neighborhood planning sought to promote, has faded away. The individual and their preferences now take precedence [

16]. Furthermore, decades into the postwar era, there is no longer any need to educate the population toward modernization.

Indeed, there are no national projects for the establishment of new towns in Western Europe in the 2000s. There is no longer any increase in the local population, and reality has overtaken the original utopian vision [

2]. The forecast is that new towns will remain a modest component of overall development. It is possible that, as was the case following World War II, new towns would be established to resettle refugees after political upheavals or in the aftermath of major disasters such as earthquakes or floods [

17]. But they would not be a significant feature.

From the 1990s, abstract values that need to be accommodated into existing towns have replaced the “total” concrete physical model. This includes Peter Hall’s Sociable City [

18], subsequently developed together with Colin Ward, which was based on small, compact, walkable cities with mixed uses that include diverse housing (including public housing), employment, local commerce, green areas, community agriculture, and public services. These are located along a backbone of public transportation and together create an urban whole greater than the sum of its parts [

19]. The concept of the ecological city, corresponding to the sustainability value, was expressed in the British government’s 2007 commitment to upgrade or convert towns into net-zero carbon zones [

20]. The value of healthy cities is promoted based on studies showing the link between mental and physical health and access to, and use of, urban open spaces [

21]. These cities are characterized by green infrastructure that includes not only green areas but also a connection to urban nature and a perception of these spaces as community anchors [

22].

And yet, what are the physical principles of new towns, insofar as there is a need to build them in Western countries? According to researchers [

17,

23,

24], such towns would be more diverse than the post–World War II new towns and would draw on the physical principles of older cities that have developed organically over time. This refers to cities structured around vibrant urban centers, compactness, walkability, and mixed land uses [

17]. They would feature resilient, diverse, aesthetic, and human-centered public spaces; a reduction in road and highway infrastructure in favor of public transportation and pedestrian and bicycle networks—with particular emphasis on rail systems and well-maintained, light-filled public spaces [

23]. It is also argued that new towns would be based on planning flexibility, economic diversity [

24], and the use of innovative technologies for managing water, energy, and waste, in order to create ecological cities [

23].

In the 2000s, new towns are rarely constructed in the Western world, and scholars now refer to desirable characteristics for new towns rather than to physical models. Physical models had lost their appeal by the 1980s. This raises several questions: What models were employed in the new towns that emerged after the 1980s? What values did these models express? What happened to urban models as they encountered reality over time? And finally, is it still possible to outline a basic physical model for an optimal new Western town? This study addresses these questions.

In light of the above, the materials and methods

Section 2 describes five research methods: selecting a representative case study; a systematic content analysis of the literature; content analysis of interviews with actors involved in the planning of new towns; schematic analysis of the models derived from the town plans; and finally, a field survey of the situation on the ground in 2025.

The results in

Section 3 include four subsections. The first

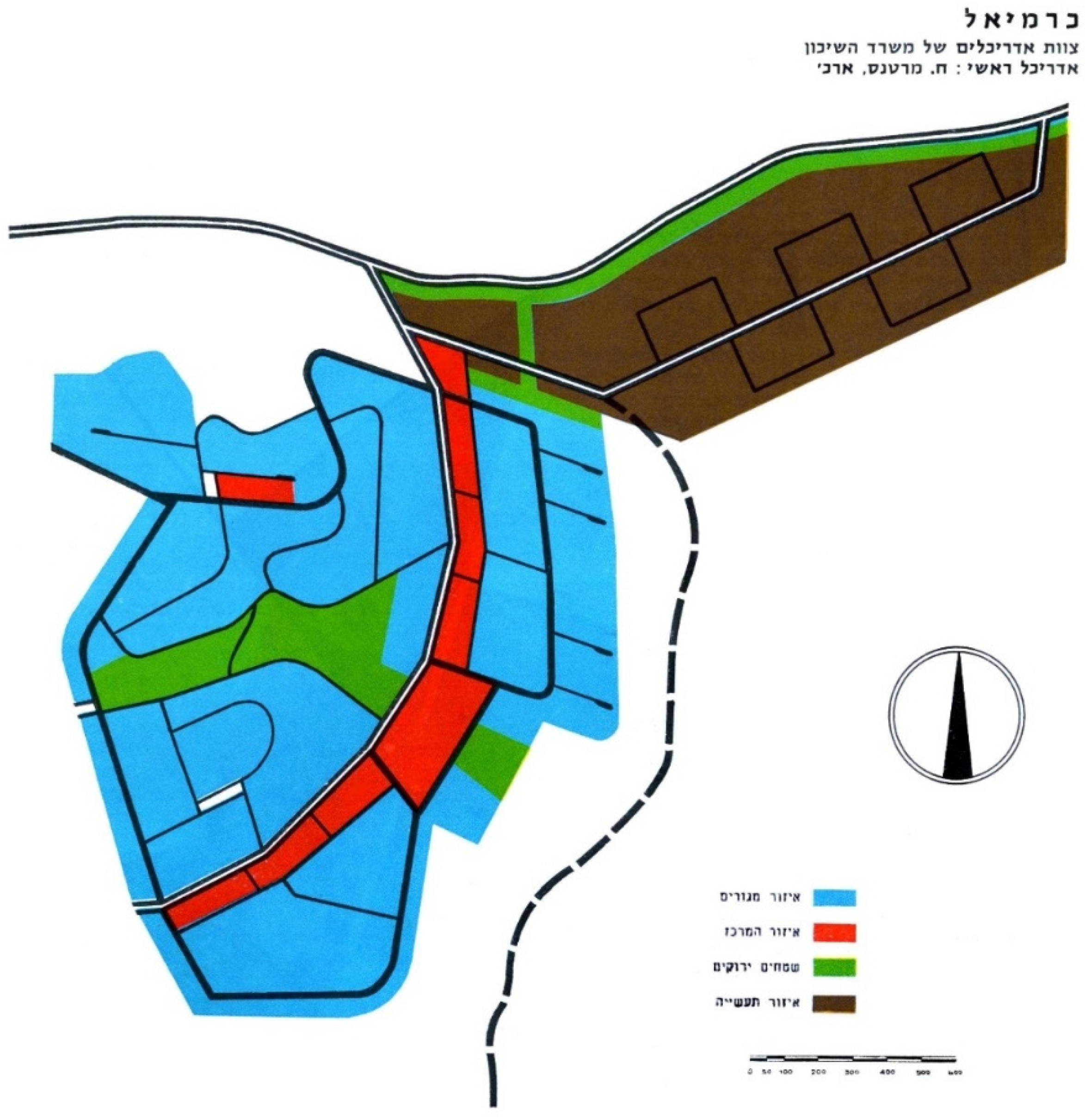

Section 3.1 reviews plans for new towns in Israel, heavily influenced by British models. The second and third, respectively, examine the plans of two new towns that were not based on a concrete Western model adapted to local needs.

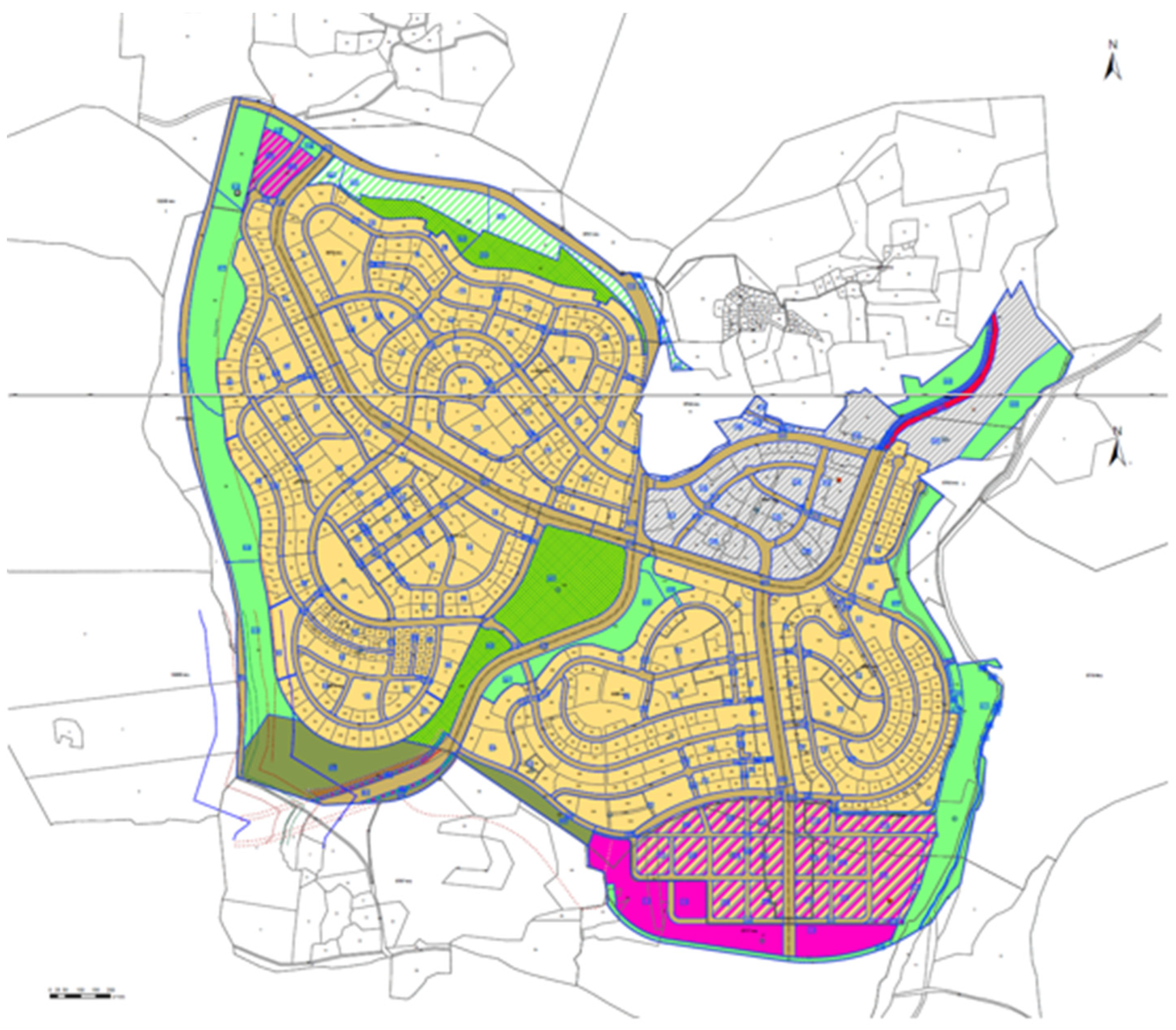

Section 3.2 focuses on Modi’in, planned in the 1990s.

Section 3.3 reviews the new town of Harish, from the 2010s. Finally, the fourth

Section 3.4 extracts the underlying schematic models from all the plans and assesses their evolvement over time.

The discussion in

Section 4 provides answers to the research questions: What were the models? Which values did they reflect? How did they change over time, and why? Finally, the conclusion (

Section 5) evaluates the models and proposes a basic physical outline for an optimal new town.

2. Materials and Methods

To address the research questions, several methods were employed. The first involved selecting a representative case study. The state of Israel was chosen for two main reasons. The first lies in the fact that in Israel, new towns are still being constructed by the state, under close governmental supervision of the planning process. In other words, there are physical models [

25]. These new towns are established to accommodate a rapidly growing population [

26] and to disperse it across the national territory. Moreover, each new town reflects—according to its time—the prevailing hegemonic values, just as the European new towns did in the postwar era. The second reason stems from Israel’s self-perception as a Western state, which draws on Western theories and values and therefore expresses them in its urban planning [

27]. In other words, Israel’s new towns serve as living physical embodiments of key European theories and hegemonic values.

Specifically, the thirty years of the British Mandate over Palestine (beginning in 1917), and the close collaboration at that time between British and Jewish planners [

28], oriented the gaze of the state’s planners (from 1948 onward) toward British planning. The British planning law was adopted and remained in effect until the passage of Israel’s own Planning and Building Law in 1965. Much like in postwar Britain, the state’s planning approach was centralized and interventionist, and the physical models of British urban planning were almost directly replicated in Israel. Israel was not unique in this regard—Britain was the pioneer of European new town planning in the postwar era [

20].

The British models were imported to Israel with necessary adaptations due to divergent circumstances: massive immigration to Israel, which resulted in a severe housing crisis; significantly limited capacity to construct adequate dwellings after the 1948 war; and the absence of a local planning tradition. Subsequently, Israel’s new towns were constructed through an orderly process of research and lessons learned, while incorporating European planning concepts.

At this point, several qualifications are in order. First, this article focuses on the physical models of the new towns. By their very nature, models are abstract constructs that articulate a very general idea. Their implementation, however, confronts them with the specific conditions of the physical site and with the concrete contents of place. To maintain the article’s focus on models, it does not address variables specific to Israel and its geopolitical circumstances, such as the siting of towns within the territory or their designation mostly for the Jewish population, which constitutes 80% of the residents within the boundaries subject to Israeli law. It also does not address the Jewish settlements in the territories occupied in 1967: in most of these areas, Israeli law does not apply, and in any case, these territories include only two new towns with populations over 30,000. One was planned before the 1980s, while the other was not originally planned as a town, but rather as a suburb.

Second, no public participation took place in the planning processes of the new towns, just as there was no public participation in similar new towns elsewhere in the West. This stems from the fact that the initial models were too abstract, and the fact that the towns were planned for populations that had not yet arrived [

29].

Third, urban models are not sensitive to the residents’ culture, since they are highly general and the future inhabitants are not yet known. At more detailed scales, and in plans specifically intended for populations whose culture is known, cultural adaptation can be observed in the fabrics and buildings of new towns [

30,

31].

Fourth, despite Israel’s Mediterranean location, the planning of the new towns did not draw on local traditions better suited to climate conditions, for example. Rather, it positioned Israel as an extension of Western Europe, certainly when it came to the models of new towns. This orientation was a result of the European origins of the Jewish planners, who constituted part of the Israeli elite and consolidated the local hegemonic mindset. Relatedly, the only school of architecture in Israel before 1992 was also dominated by the Eurocentric approach of its founders and leaders [

32]. As previously discussed, this orientation was informed in part by the example provided by British planning.

The study’s second method employed a content analysis approach based on a systematic review of both the historical planning literature and contemporary sources.

The third method included interviews with professionals who worked on the plans for the new towns or guided their planning process in the years 2001–2025, on behalf of the Israeli Ministry of Construction and Housing. This analysis identified the theories and precedents informing this planning and their results on the ground.

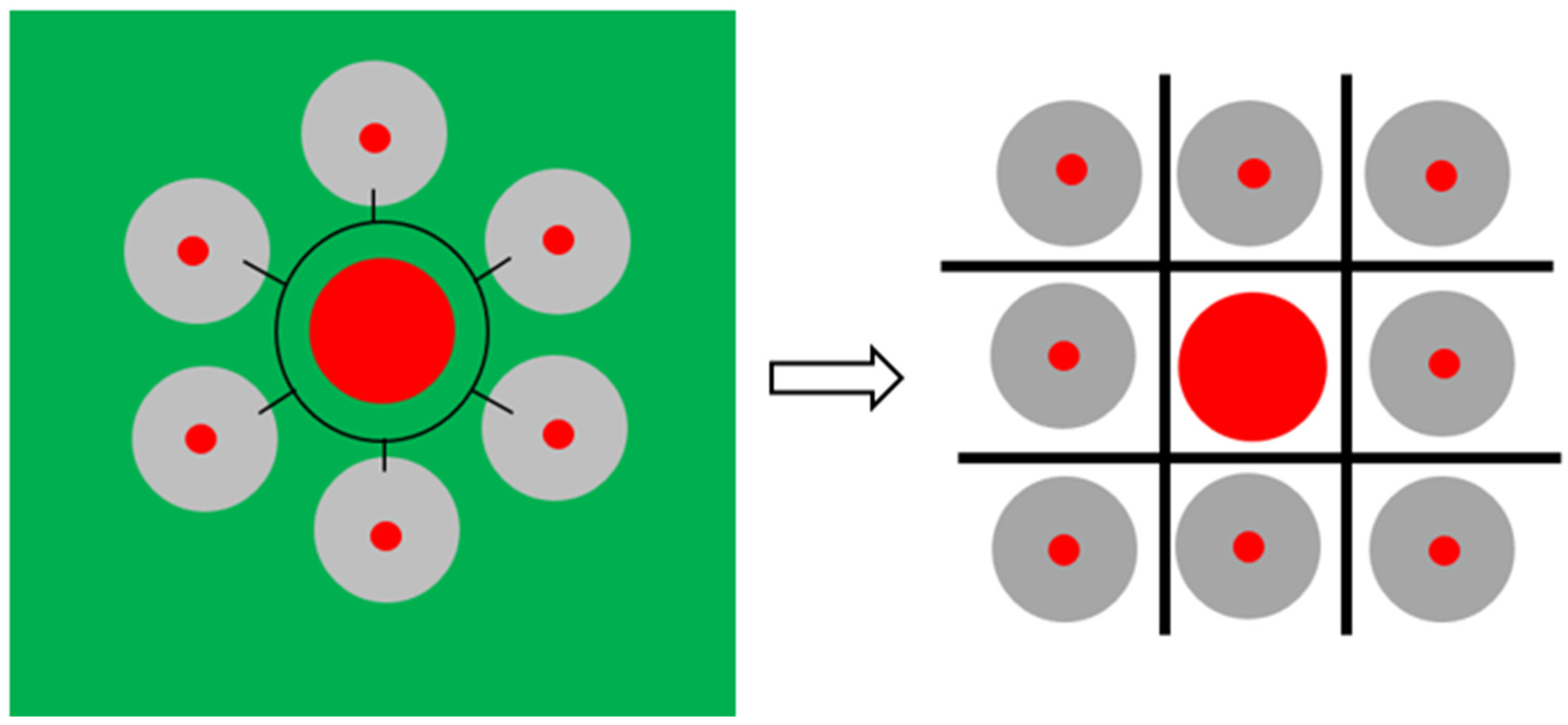

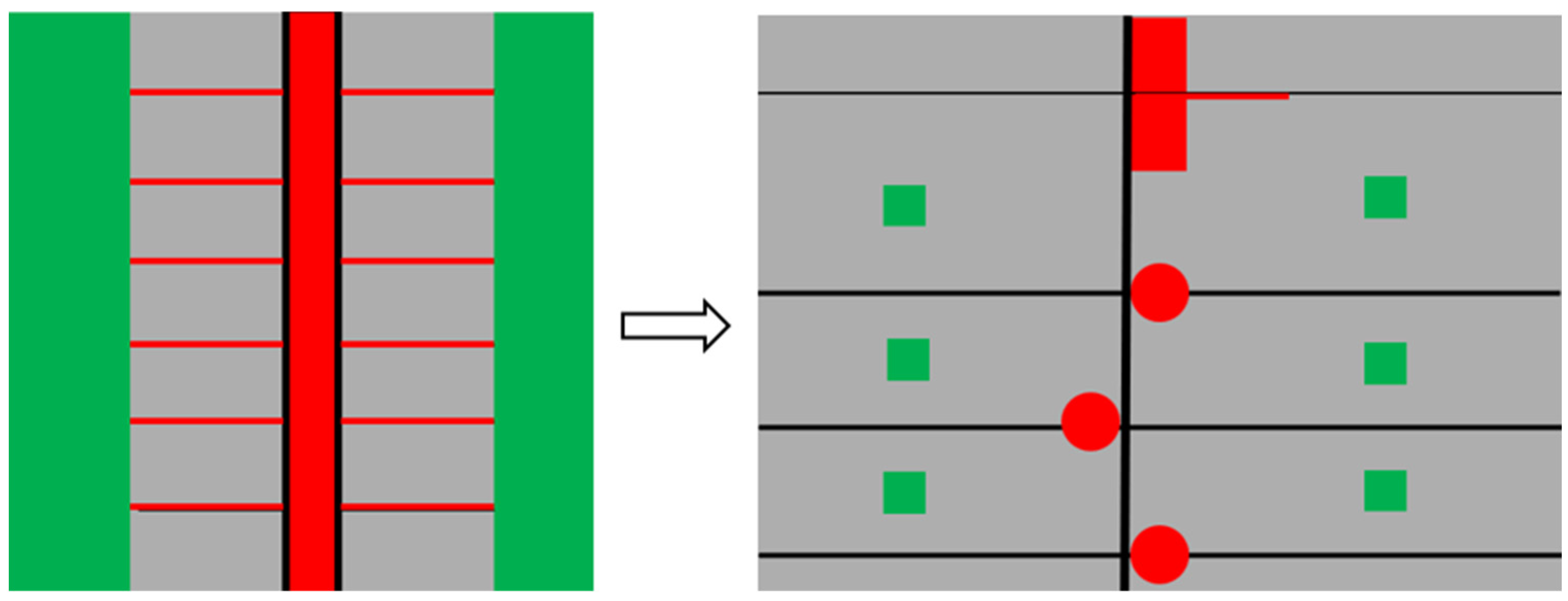

The fourth method applied was analysis of urban plans based on four fundamental components present in every city and responsible for shaping its model: residential areas, community and urban centers, green spaces, and the mobility network. This analysis was conducted in two phases: at the time of initial construction and after years. This enabled us to trace both the underlying logic that generated the city and the changes it underwent as it confronted reality.

To validate the findings, a fifth method was employed: a field survey and the collection of observations. The findings are illustrated in the photographs presented following the graphic diagrams.

The content analysis of the literature review and interview findings addressed the reasoning underlying the specific planning decisions: the choice to adopt European models, the drawing of lessons from earlier models, and the values that planners sought to embed through these models regarding the balancing of communality and individualism. The analysis of the plans and of the situation on the ground employed paired schematic graphic schemes—of the original plans and of the situation in 2025—in order to identify the differences between the initial models and their subsequent evolution.

4. Discussion

The literature review indicates that Western Europe no longer develops models for new towns, as it has become clear that cities are too complex to predict their future development [

2,

14,

15,

16], and that pre-modernist cities are superior to the planned new towns that followed [

11,

12,

13]. It has also been understood that, instead of physical models for new towns, since the 1990s, recommendations have been advanced for improved planning [

17,

23,

24] based on values such as communality, ecology [

20], and health [

21,

22]. Nevertheless, since new towns are still being planned with reference to these same Western values, as demonstrated in the present findings, the question arises as to what can be learned from them.

In general, setting aside the 1950s radial flower model of the disconnected city, the Israeli new town models from the 1960s onward oscillate between two main motifs: the grid and the linear. However, one must not be misled by their visual similarity, as these models can be used for entirely different purposes.

The grid model of Be’er Sheva from the 1960s and that of Modi’in from the 1990s were designed for opposite purposes. While the wide, traffic-oriented roads of Be’er Sheva aimed at separating the neighborhoods—and succeeded—the wide roads in Modi’in, embracing gardens, public buildings, and neighborhood-level commercial centers, were intended to connect the neighborhoods—albeit without much success. The linear model of Karmiel was highly constrained: the city was planned in the 1960s around a longitudinal, pedestrian-only CBD, from which perpendicular pedestrian streets extended into the neighborhoods. Along these streets, daily-use public and commercial functions were located. In contrast, the main street forming the linear axis of Harish (planned in 2010) is only part of a more diverse urban system. Unlike Karmiel’s original design, Harish includes intra-neighborhood public spaces and gardens that are not inherently linked to the central street, as well as a separate CBD that adjoins the central axis, which extends beyond it. Unlike the earlier models, which follow a fixed and repetitive schema, Harish is a city of combinations, without a single comprehensive model. Thus, it includes an urban street, a CBD, and neighborhood centers.

The explanation for these differences lies not only in the technical lessons learned from one model to another, but also in the hegemonic values and conceptions shaping them. Over the seven decades of Israel’s existence, one can observe a shift from the imposed communality and rurality characteristic of the newly founded state toward urban individualism. The flower model of Be’er Sheva in the 1950s and the grid model that replaced it both suppressed urbanity and promoted neighborhood-scale living, reflecting a desire to create cohesive, melting pot-style immigrant communities. Karmiel’s walkable linear model in the 1960s expressed an aspiration for communal urbanity. This was manifested in planning that was based on a single pedestrian neighborhood path and a single urban path (the CBD), intended to maximize human encounters. In other words, the need for urbanism was already acknowledged, but not the value of free choice or individualism. In the 1990s, the desire for residents’ free choice was expressed in Modi’in’s navigable grid model, particularly in the externalization and accessibility of gardens and public buildings, so that all residents could select from the city’s offerings. From the 2010s onward, the aspiration for vibrant urbanity and individualism was integrated into the composite city model: Harish included a variety of elements—a mixed-use main street, a CBD, and separate community centers. These values were joined by additional Western conceptions such as flexibility of use, connectivity, and ecological awareness. These were expressed through mixed uses, compact development, a continuous public transport corridor across the city, and a wealth of ecological gardens. The value of communality was not abandoned but reflected in intra-neighborhood public spaces.

An examination of how the models have changed over time reveals that such changes in values and architectural fashions or practices are difficult to implement on the ground. The flower model of Be’er Sheva has indeed been replaced by a grid model, but its neighborhoods remain disconnected. The linear city model of Karmiel spans, in practice, only 240 m. The idea of a 1.7 km-long urban center, with movement based solely on pedestrian circulation—within both the neighborhoods and the CBD—has been superimposed on the physical and human reality and, therefore, proved unfeasible. Instead of a continuous linear center, neighborhood centers have been built adjacent to the city’s main traffic artery. Modi’in grid model, though seemingly open to change, has also proven difficult to adapt. To this day, only a handful of shops have opened along residential streets, meaning that even buying a loaf of bread requires residents to descend to the large supermarket in the valley, outside the residential neighborhoods. Finally, Harish’s composite model has also failed when seeking to impose itself on the residents. Paradoxically, the very effort to predesign a main street that would include everything to ensure success has ended up being detrimental. Too wide, too long and too monotonous, it is out of sync with the economic capacity of an emerging peripheral city. As a result, it has become a landscape asset rather than an urban one within the city’s early years. In other words, the more confident the planning is in its omniscience, the more it tends to fail over time.

5. Conclusions

This article focuses on the physical models of new towns. It should be emphasized that physical models are abstract constructs, and their success or failure is always mediated by contextual factors such as location, governance, and social composition, and the present paper deliberately restricts itself to the formal/typological dimension, leaving broader contextual analysis for future work.

In terms of the lessons to be derived from the specific cases discussed in this article, it becomes apparent that two planning motifs are clearly evident in Israel’s new town, throughout its history: grid and linear planning. Also evident from the foregoing review is the fact that these same motifs can express different, even opposing, values. Two broader approaches to planning also arise from this history: rigid and repetitive planning on the one hand, and on the other, planning that views the city as a composition—a diverse collection of spaces and related behavioral patterns. Based on both the Israeli experience and the European experience up to the 1980s, it is evident that the more rigid the planning, the more problematic it becomes. It imposes its internal logic on the residents and makes future changes more difficult to implement.

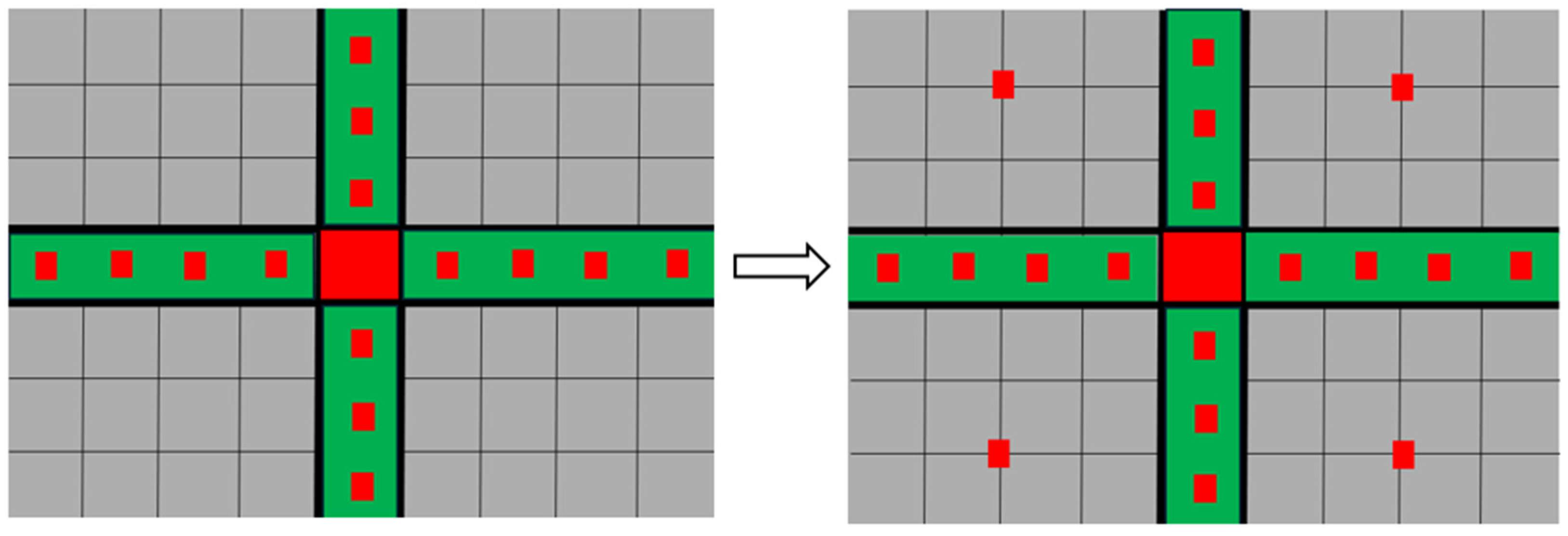

That being said, are there any operational conclusions that can inform physical modes of newer new towns, so that these become as functional as possible even along their extended process of emergence and becoming? Can physical conclusions be drawn regarding the four urban components that appeared in the graphic schemes: the mobility network (in black), urban and neighborhood centers (in red), green areas (in green), and residential zones (in gray)? Ultimately, new towns continue to be constructed—particularly in East Asia, South Asia, and Africa [

1,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65], and it is conceivable that they would also emerge in Western countries in response to climatic or demographic changes that are as yet unforeseeable [

17]. Such towns will necessarily undergo a long and incremental process of development before reaching their intended scale and function.

Regarding mobility networks, the Israeli experience across all models suggests that the grid model is more conducive to change and is therefore preferable to its linear counterpart, which relies on a single central axis. It appears that establishing a hierarchy among the streets is advisable, as it provides perceptual clarity and makes the city more accessible. Furthermore, the denser the grid—especially in central areas—the more flexible the built environment along it can become, thus better accommodating multiple uses and enabling more vibrant urban life.

Regarding civic centers, it has been found that it is preferable not to plan a complete CBD in advance, but rather to adopt a bead-string approach, as evident in Karmiel’s case. That is, small clusters of retail, employment, and services located close to residential areas and connected by a transportation axis. These can create a fragmented yet functional whole during the early stages of urban development and may later either coalesce into a continuous center if the city grows and densifies or evolve in entirely different directions in response to unforeseen realities.

As for green spaces, they appear to contribute to urban beauty but often fail to live up to usage expectations—even when adjacent to public or commercial buildings (as evident in Modi’in). Therefore, small, visible intra-neighborhood green spaces located along the street, as in Harish, provide a better setting for community life, especially in the city’s early development phases. Note that this does not detract from the importance of designating a large green area with scenic and ecological value to serve as a central park.

Finally, regarding residential development, the long-term value of implementing the Garden City theory becomes evident. Its Israeli interpretation, as seen in Modi’in, where residential building height has been limited to treetop height, as well as in other cities that evolved from planned villages [

66] was expressed early on in the construction of houses on relatively small plots, leaving part of the plot open for trees and green areas. Green spaces within the residential plots provided flexibility with regard to building density. In the initial stage of the town, when the population was still small, the buildings were modest in scale and embedded in greenery. Over time, in response to market forces and ecological values, multi-story buildings replaced the original houses, at the expense of the open and green spaces within the residential plots. In addition, changes in spatial usages were easier to implement due to the small plot sizes and relatively limited shared spaces. Therefore, the recommendation is to initially plan a new town as a green city, rich in vegetation. This greenery should be an integral part of the residential plots, so that, when the time comes, such a city can more easily develop intensive urbanism according to its evolving needs.