How the Internet Celebrity Economy Influences the Gentrification Trend of Historic Conservation Districts: Taking Tanhualin District in China as an Example

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Status

2.1. The Impact of the Internet Celebrity Economy on Physical Space

2.2. The Association Between the Internet Celebrity Economy and Gentrification

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Methods

4. Results

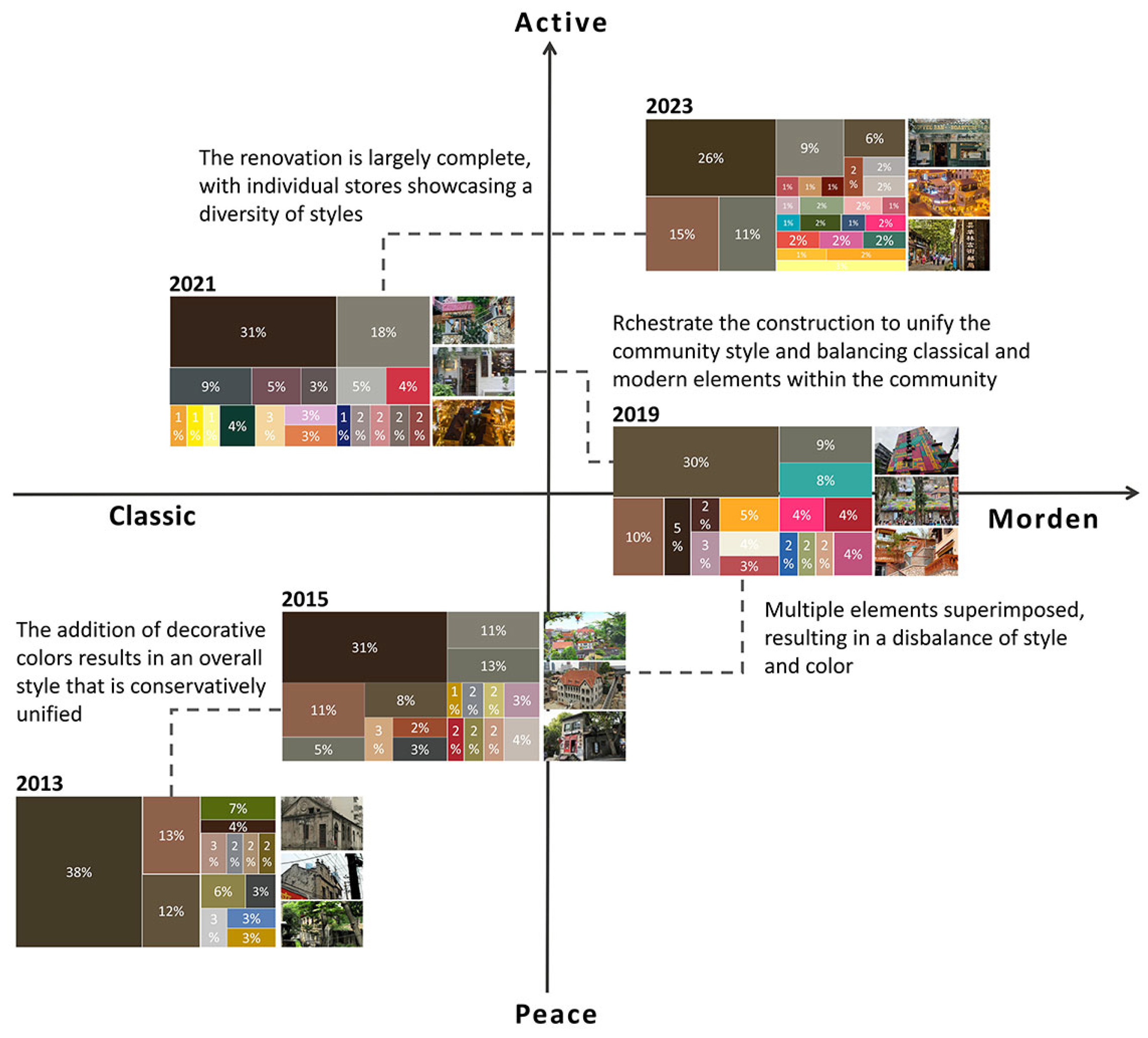

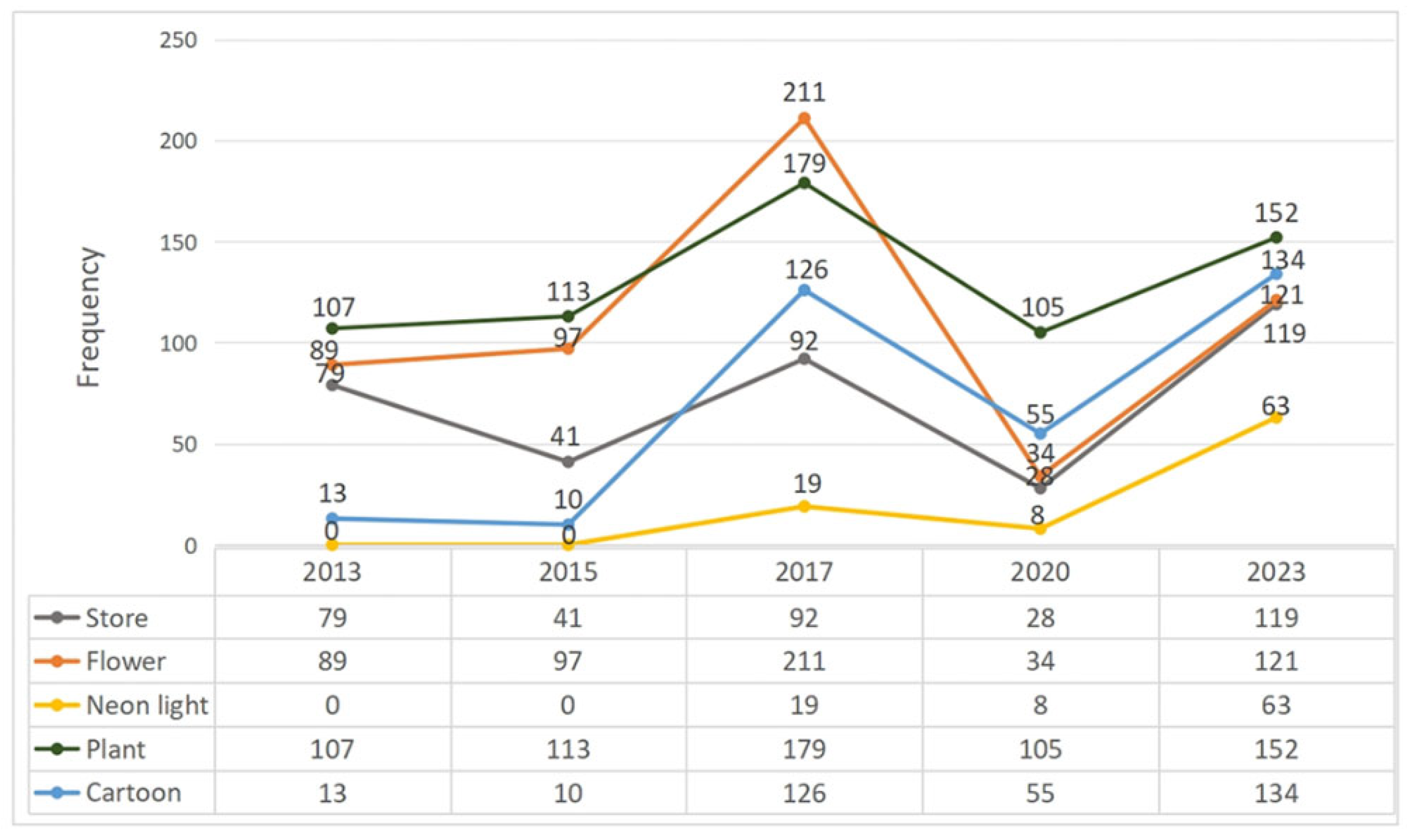

4.1. Spatial Color and Decorative Changes

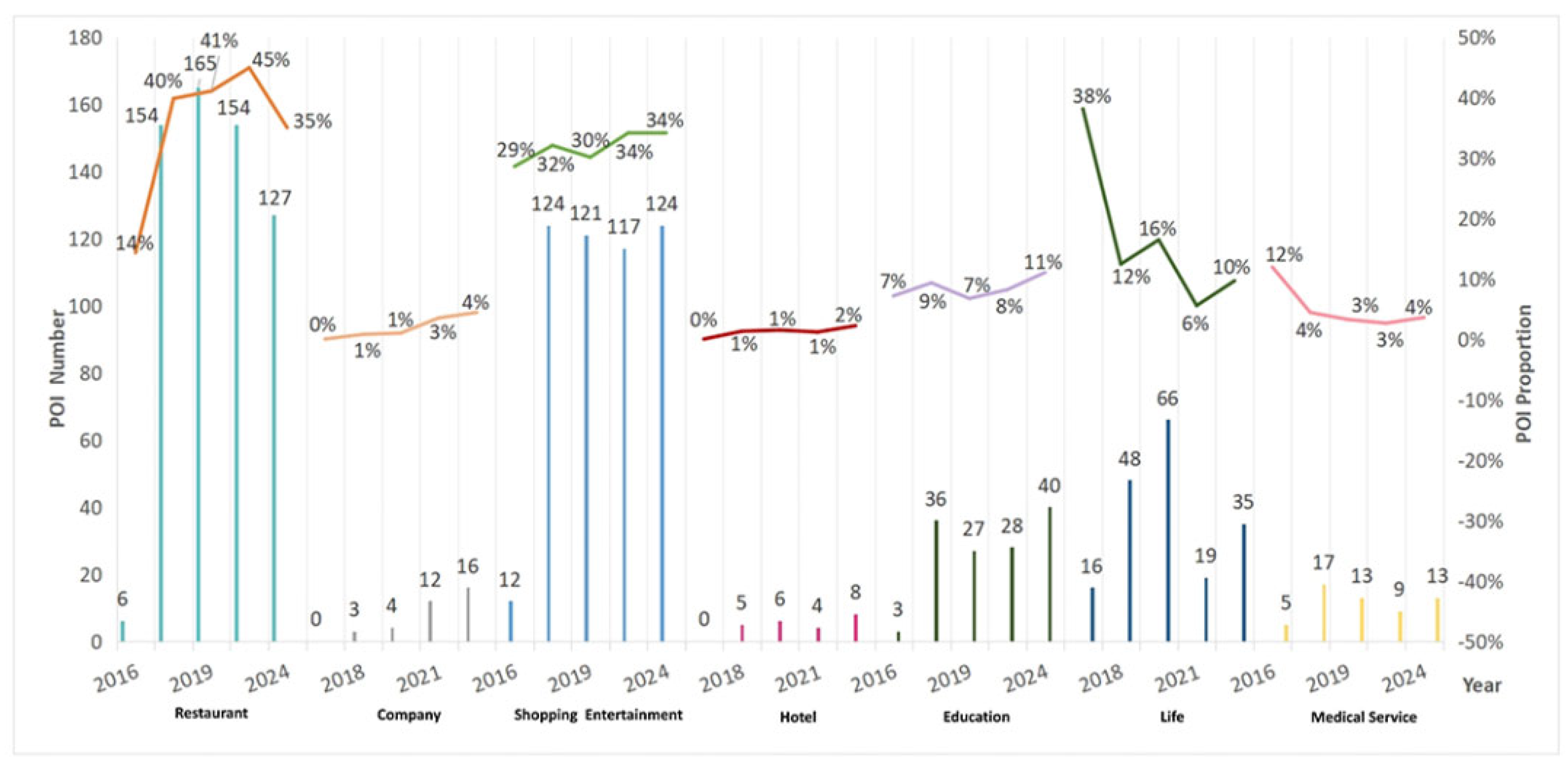

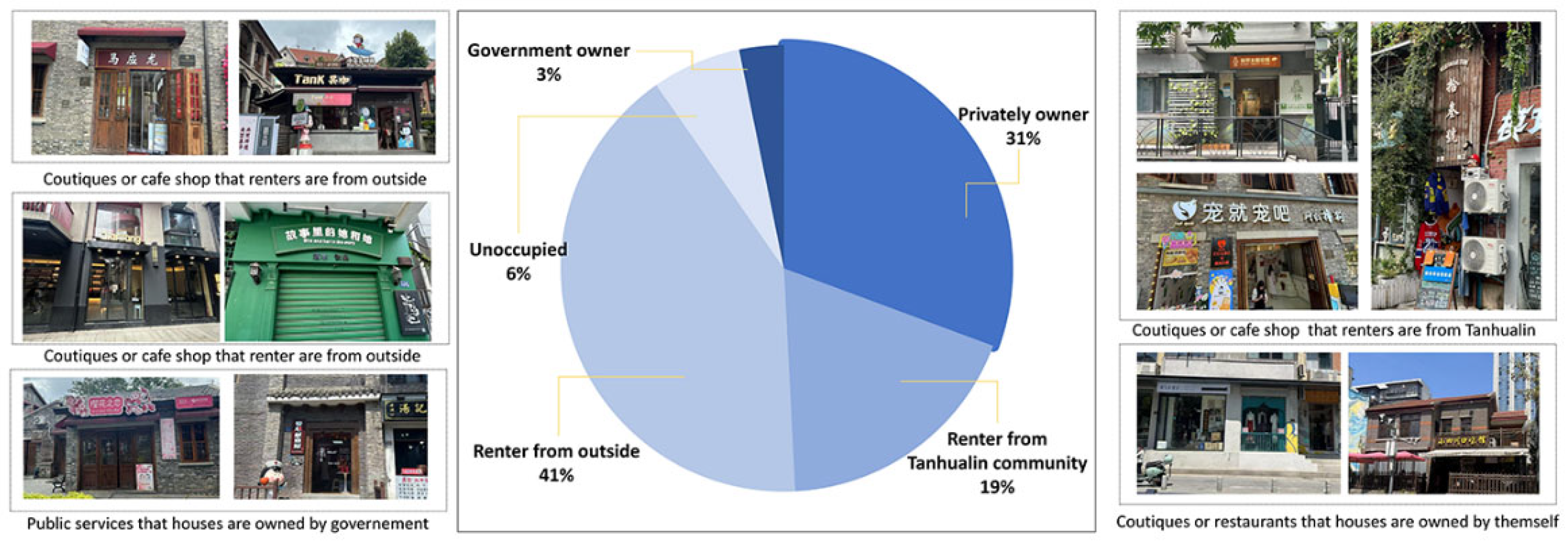

4.2. Business Format Changes and Rent Fluctuations

4.3. Tourist and Native Resident Displacement

4.4. Comparison of Traditional Gentrification and Internet Celebrity Economy Gentrification Characteristics

5. Discussion

5.1. The Transfer of Aesthetic Discourse Power

5.2. The Protection of the Interests of Local Residents

5.3. Harmonious Coexistence of Diverse Gentrification Subjects

5.4. Study Value and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSM | Open Street Map |

| PCCS | Practical Color Coordinate System |

| POI | Point Of Interest |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| IP | Influential Property |

| FMCGs | Fast-Moving Consumer Goods |

References

- Han, B.; Hu, H.; Zhang, J. The Reconstruction and Countermeasures of Internet-Famous Street and Lane Space in Old Town from the Perspective of Space-Time Dis-embedding: A case Study of Xingshi Community in Xuzhou. Urban Dev. Stud. 2025, 31, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Lin, M.; Jian, J. Pathways for Traditional Villages’ Transition from “Internet-Famous” to “Long-Term Popularity” in the Flow Economy: A Case Study of Xunpu Village, Quanzhou-All Databases Available. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsvoort, I.; Uitermark, J.L. Seeing the Street through Instagram. Digital Platforms and the Amplification of Gentrification. Urban Stud. 2022, 59, 2857–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gu, H.; Shi, M. The Influence of Commercial Gentrification on Surrounding Old Neighborhoods Based on Field Theory: A Case Study of Daci Temple Community of Chengdu. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 2726–2741. [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, C.N. The Impact of Urban Renewal and Gentrification on Urban Fabric: Three Cases in Turkey. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2003, 94, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Yu, P.; Zhao, X.; Su, Y. Research on the Representation and Dynamic Mechanism of Environmental Gentrification of Xian, China. City Plan. Rev. 2023, 47, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Luo, Z.; Qin, L.; Wang, J.; Bai, X. Research on Shadow Education Gentrification and its Formation Mechanism: A Case Study of Lanzhou. Hum. Geogr. 2024, 39, 17–28+152. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Yin, S.; Chen, P. Commercial Gentrification in the inner City of Nanjing, China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 426–442. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M. Study on Commercial Gentrification in the Surrounding Area of Daci Temple, Chengdu. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y. A Review of Empirical Research on Gentrification in Contemporary China: Characteristics, TOI and Prospects. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 36, 5–14+36. [Google Scholar]

- He, S. New-Build Gentrification in Central Shanghai: Demographic Changes and Socioeconomic Implications. Popul. Space Place 2010, 16, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattuso Densmore, A.M. Picturesque Portraiture: The Composition of Reality in Hawthorne, Melville, and James. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA, June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Avraham, E. Cities and Their News Media Images. Cities 2000, 17, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism Gentrification: The Case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. Social Media for Collaborative Planning: A Typology of Support Functions and Challenges. Cities 2022, 125, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Kuang, X. Image of a City in the Local and Global Media: Suzhou as a Case. Cities 2023, 143, 104593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlee, S.; Chung, N.; Chulmo, K. Exploratory Research on Sense of Place and Perception of Gentrification in Urban Street Tourism: Focusing on Participation Observation in off-Line and Instagram Space. J. Hosp. Tour. Stud. 2016, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Xiong, H.; Tang, M.; Ye, J. The Evolution of User Sentiment and the Attribution of Negative Comments in University Emergency Network Public Opinion. Inf. Sci. 2025, 43, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhu, X.G.; Song, W.X.; Ma, G.Q. Commercial Gentrification Driven by Cultural Consumption in Neighborhoods Around University Campuses: A Case Study of the Original Campuses of NJU and NNU. City Plan. Rev. 2018, 40, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P.C.; Jansson, A. Communication Geography: A Bridge Between Disciplines. Commun. Theory 2012, 22, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, H. The Media and the Transformation of the Public Sphere: A Contribution for a Critical Political Economy of the Public Sphere. Eur. J. Commun. 1996, 11, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A. Mediatization and Social Space: Reconstructing Mediatization for the Transmedia Age. Commun. Theor. 2013, 23, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Visibility Labour: Engaging with Influencers’ Fashion Brands and #OOTD Advertorial Campaigns on Instagram. Media Int. Aust. 2016, 161, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Bowes, T. Instagram Made Me Buy It’: Generation Z Impulse Purchases in Fashion Industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, M.; Tanguay, G.A. Analysis of the Determinants of Urban Tourism Attractiveness: The Case of Québec City and Bordeaux. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radmila, Ž.; Jelena, G.; Ivana, B. The Impact of Social Media on Tourism. In Proceedings of the Prva Međunarodna Konferencija Sinteza, Belgrade, Serbia, 25–26 April 2014; pp. 758–761. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Kalandides, A. Rethinking the place brand: The interactive formation of place brands and the role of participatory place branding. Environ. Plan. 2015, 47, 1368–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.H.D.S. Place branding in strategic spatial planning: A content analysis of development plans, strategic initiatives and policy documents for Portugal 2014–2020. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2015, 8, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, E.; Eshuis, J.; Klijn, E.-H. The Effectiveness of Place Brand Communication. Cities 2014, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polson, E. From the Tag to the #hashtag: Street Art, Instagram, and Gentrification. Space Cult. 2024, 27, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, N.; Petzer, D.J. Examining the Luxury Apparel Behavioural Intentions of Middle-class Consumers: The Case of the South African Market. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 955–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Xiang, J. New Rural Development and Rural Revitalization Path in the Era of Mobile Internet. City Plan. Rev. 2019, 43, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Lin, Y.; Hooimeijer, P.; Monstadt, J. Measuring Social Network Influence on Power Relations in Collaborative Planning: A Case Study of Beijing City, China. Cities 2024, 148, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; De Kerviler, G.; Guidry Moulard, J. Authenticity under Threat: When Social Media Influencers Need to Go beyond Self-Presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubler, K. Influencers and the Attention Economy: The Meaning and Management of Attention on Instagram. J. Mark. Manag. 2023, 39, 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zeng, P. New Internet Celebrity Economy in the Context of Social Circle and Sreatification: Evolutionary Path, Value Logic and Operational Risk. Editor. Friend. 2019, 12, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Arkaraprasertkul, N. Gentrification and Its Contentment: An Anthropological Perspective on Housing, Heritage and Urban Social Change in Shanghai. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1561–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcindor, M.; Müllauer-Seichter, W.; De Gregorio Hurtado, S.; Medeiros, L.; Loda, M.; Jackson, D. Approaches to Collective Cognition in the Historic Centre of Madrid: An Erasmus Interdisciplinary Experience. Land 2025, 14, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Qian, Z. “Art District without Artists”: Urban Redevelopment through Industrial Heritage Renovation and the Gentrification of Industrial Neighborhoods in China. Urban Geogr. 2024, 45, 1006–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X. Historicising Wanghong economy: Connecting platforms through Wanghong and Wanghong incubators. Celebr. Stud. 2020, 12, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L. Influencers and Social Media: Gentrification Aesthetics and Prosumption through China’s Wanghong Economy. Urban Geogr. 2025, 46, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Ahmad, Y.; Mohidin, H.H.B. Spatial Form and Conservation Strategy of Sishengci Historic District in Chengdu, China. Heritage 2023, 6, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N. A Preliminary Study of Slow Traffic System to Activate the Vitality of Historic Districts Take Wuhan Tanhualin Historic District as an Example. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 647, 12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; He, C.; Lv, S. Sustainable Renewal of Spontaneous Spatial Characteristics of a Historical–Cultural District: A Case Study of Tanhualin, Wuhan, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, R.W. A Proposal to Apply the Historic Urban Landscape Approach to Reconstruction in the World Heritage Context. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2018, 9, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhuang, H.; Cui, Y.; Deng, J.; Ren, J.; Long, H. A Dichotomy Color Quantization Algorithm for the HSI Color Space. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Shou, Y.; Wen, L.; Xu, F.; Zhang, L. Color Detection of Printing Based on Improved Superpixel Segmentation Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Ma, Y.; Yahya, M.; Ahmad, B.; Nazir, S.; Haq, A.U. Object Detection through Modified YOLO Neural Network. Sci. Program. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lu, X. How Was the Color Harmony Thought Be Positioned and Applied in Japan’s Landscape Color Planning. Urban Plan. Int. 2021, 36, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Edensor, T.; Cheng, J. Beyond Space: Spatial (Re)Production and Middle-Class Remaking Driven by Jiaoyufication in Nanjing City, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, C.; Jude, H. Deep Learning and TextBlob Based Sentiment Analysis for Coronavirus (COVID-19) Using Twitter Data. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Tools 2022, 31, 2250011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, E.; Ducange, P.; Marcelloni, F. Monitoring Negative Opinion about Vaccines from Tweets Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 Third International Conference on Research in Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (ICRCICN), Kolkata, India, 3–5 November 2017; pp. 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Gu, Y.; Su, X.; Ran, L.; Zhang, K. Spatial Analysis of Urban Historic Landscapes Based on Semiautomatic Point Cloud Classification with RandLA-Net Model—Taking the Ancient City of Fangzhou in Huangling County as an Example. Land 2025, 14, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequeux-Dincă, A.-I.; Gheorghilaş, A.; Tudor, E.-A. Empowering Urban Tourism Resilience Through Online Heritage Visibility: Bucharest Case Study. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, Z. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urabn Places; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sigler, T.; Wachsmuth, D. New Directions in Transnational Gentrification: Tourism-Led, State-Led and Lifestyle-Led Urban Transformations. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3190–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Business Type | Location | Opening Time | Rent Changes (in Month) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bubble Tea Shop | Tanhualin Road Side | 2021 | 230 Ұ/m2–300 Ұ/m2 |

| Bubble Tea Shop | Tanhualin Road Side | 2022 | 280 Ұ/m2–350 Ұ/m2 |

| Bubble Tea Shop | Fanyuehui Plaza | 2022 | 200 Ұ/m2–240/m2 |

| Cafe | Tanhualin Road Side | 2020 | 200 Ұ/m2–220/m2 |

| Convenience Shop | District Center | 2018 | 100 Ұ/m2–250/m2 |

| Hanfu Experience Store | Tanhualin Road Side | 2019 | 129 Ұ/m2–135 Ұ/m2 |

| Cate cafe | District Center | 2021 | Self-owned |

| Cate cafe | Tanhualin Road Side | 2022 | 220 Ұ/m2–230 Ұ/m2 |

| Restaurant | Alleys | 2019 | Self-owned |

| Cultural and Creative Store | District Center | 2021 | 210 Ұ/m2–230 Ұ/m2 |

| Cultural and Creative Store | Tanhualin Road Side | 2021 | Government owned |

| Pottery | Alleys | 2018 | 35 Ұ/m2–45 Ұ/m2 |

| Pottery | Alleys | 2021 | 55 Ұ/m2–60 Ұ/m2 |

| handicraft shops | Alleys | 2020 | Self-owned |

| Business Driven by Internet Celebrity Economy | Business Driven by Gentrification | |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Reconstruction | Keep the original style + Instagrammable decorations | Normally, completely rebuild |

| Lease form | Local residents’ owner-occupied housing rentals | Developer-Led Build-to-Rent |

| Lease fee | Moderate overall growth, with significant surges among high-revenue shops | Whole area significant surges |

| Business Format | More service and experiential shops | High-end brand, chain stores, boutiques |

| Operators | Local Residents + Some operators from outside | Developer or chain stores |

| Consumers | Tourists, young people and all different groups | Elite class |

| Development Entity | Government, local residents, some operators from outside | Government or other developers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, Y.; Xu, J.; Geng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, J. How the Internet Celebrity Economy Influences the Gentrification Trend of Historic Conservation Districts: Taking Tanhualin District in China as an Example. Land 2025, 14, 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091806

Yao Y, Xu J, Geng H, Zhang Y, Qiao J. How the Internet Celebrity Economy Influences the Gentrification Trend of Historic Conservation Districts: Taking Tanhualin District in China as an Example. Land. 2025; 14(9):1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091806

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Yibing, Jiaming Xu, Hong Geng, Yuanzhi Zhang, and Jing Qiao. 2025. "How the Internet Celebrity Economy Influences the Gentrification Trend of Historic Conservation Districts: Taking Tanhualin District in China as an Example" Land 14, no. 9: 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091806

APA StyleYao, Y., Xu, J., Geng, H., Zhang, Y., & Qiao, J. (2025). How the Internet Celebrity Economy Influences the Gentrification Trend of Historic Conservation Districts: Taking Tanhualin District in China as an Example. Land, 14(9), 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091806